The Spinoff

The Sunday Essay April 9, 2023

The sunday essay: the cancelled springbok tour of 1973.

- Share Story

Fifty years ago a rugby tour of New Zealand was scheduled. After loud and often rowdy protest against it, the tour was called off. Trevor Richards remembers the cancelled Springbok Tour of 1973.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

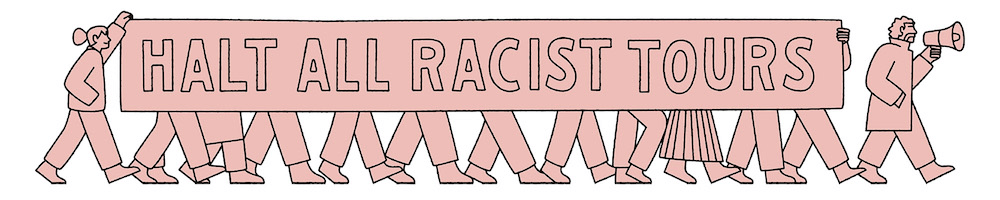

Illustrations by Joe Carrington

On April 10, 1973, then prime minister Norman Kirk told a crowded press conference that he had written to the New Zealand Rugby Football Union (NZRFU) advising that the government saw “no alternative, pending selection on a genuine merit basis”, to a postponement of the proposed Springbok tour to New Zealand.

Given the history of our rugby relationship with apartheid South Africa, the decision was somewhat surprising. Less than two decades earlier, the 1956 Springbok rugby tour had gripped the nation. Even the New Zealand Communist Party supported it, but by the late 1960s, times were changing.

New Zealanders were being confronted with a stark challenge. Eric Gowing, the Anglican Bishop of Auckland, was blunt: “What you think about sporting contacts with South Africa depends on what you think about racism.”

Whether the 1973 Springboks tour should proceed became a major issue. Its cancellation was an early indication that New Zealand was beginning to shed the rigid, conservative, “rugby, racing and beer” assimilationist values of the post World War II era.

At the time, New Zealanders were well aware of protesters’ commitment to disrupt the tour should it proceed. Almost none were aware of the behind the scenes “dialogue” between the prime minister Kirk and the leadership of the Halt All Racist Tours movement (HART) leading up to the tour’s cancellation.

HART had been formed in 1969 to stop the 1970 All Black tour of South Africa. Looking back, we were Pollyanna at the barricades. Our 1970 strategy had been based on the assumption that those in positions of power – the government and the NZRFU – could be influenced by facts, logic and morality. What we discovered was that prejudice and self-interest were immune to such appeals. A new approach was needed.

By the end of March 1971, HART and CARE (the Citizens’ Association for Racial Equality) had announced policies of “non-violent disruption” of apartheid sport. Mr Niceguy was just too easy to ignore. There needed to be the promise of a frontal attack on such tours.

While policies of direct action are what HART and CARE were best known for, most of our time and money was spent on education. Hundreds of thousands of leaflets were distributed. We published a monthly tabloid newspaper. Meetings were held in draughty halls up and down the country. Between March 1971 and February 1973, five overseas speakers toured New Zealand.

The 1972 general election campaign did not fill anti-apartheid hearts with any great confidence. The ruling National Party declared its support for the tour. Although the opposition Labour Party did its best to avoid the issue, leader Norman Kirk promised not to stop the tour. On November 25, twelve years of National Party rule came to an end. Labour was elected with a whopping 23-seat majority. What would the new government do?

On January 3, 1973, the Supreme Council for Sport in Africa (SCSA), the body which coordinated and promoted Africa’s anti-apartheid sports policies, called on all Commonwealth countries in Africa to withdraw from participating in the 1974 Christchurch Commonwealth Games if the Springbok tour went ahead. It was New Zealand’s first direct taste of the strength of independent Africa’s opposition to apartheid.

On January 23, the new prime minister sent the NZRFU a letter, attaching a report on the implications of the tour for New Zealand’s international standing, for internal race relations and for law and order. The report concluded: “it is the considered police view that the tour would engender the greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known.” On the international front, the report said there was “a virtual certainty that the Commonwealth Games would … either have to be cancelled or be a failure.” Serious concerns were expressed about the tour’s potential impact on race relations.

Margaret Hayward, Kirk’s Private Secretary, wrote in Diary of the Kirk Years that “the prime minister is optimistic. He appeared to believe that if the rugby union was treated like a group of responsible men, they were more likely to act like reasonable men.” If he had a concern, it was about anti-apartheid groups.

At the end of January, his message to an anti-apartheid deputation had been to “cool it”. We could understand his logic. If he was going to stop the tour, he could not be seen to be giving in to pressure from HART and CARE. But the “if” was a very big one. Labour’s election promise not to cancel the tour sat front and centre in our minds.

In early February, following a meeting to consider the prime minister’s letter, the Rugby Union announced that “arrangements for the tour are proceeding”. When a radio journalist asked if this was the union’s last word on the tour, NZRFU chairman Jack Sullivan smothered the microphone “with a big fist”. New Zealand’s rugby authorities in 1973 were men who fondly remembered the 1956 tour. The NZRFU was never of its own volition going to stop the tour.

Stories in the daily metropolitan press started speculating that the tour might be stopped “in the public interest”. I didn’t believe it.

In the second week of February, HART issued a comprehensive statement outlining what it would do if the tour proceeded. “Let everyone know that … the whole of New Zealand will have to be guarded on a 24 hour a day, seven days a week basis.” Many papers accorded it front-page lead status.

The statement infuriated rugby supporters. The prime minister issued an angry statement: “Richards, you are not running the country.” The police announced that they were considering prosecuting me for the statement. Some leading figures within the movement considered that I had overstepped the mark. Sometimes, it could feel a bit lonely.

At a HART meeting in Ashburton a few days later, around 600 pro-tour supporters turned out in an effort to prevent me from speaking. The meeting went ahead, but only after a number of their placards had come crashing down on my head.

Privately, the PM was remaining optimistic. Hayward wrote in her diary: “Everyone else seems to be making moves, but Mr. K remains quietly confident. He just grins and tells us he’s moving with ‘dynamic caution’.”

In mid February the Rugby Union met with the prime minister. Kirk’s concerns were ignored. The NZRFU announced the tour was proceeding. Asked what the government’s next step would be, Kirk said “wait and see I guess”. Asked to be more specific about timing, he said “soon, in the soonest sense of soon”. By now, most political commentators were of the view that Kirk would cancel the tour. We could see no evidence for this.

At the end of February, the prime minister met with a deputation from the pro-tour lobby. Some time later, a full transcript of the meeting fell off the back of a truck and into HART’s hands. The prime minister had told the delegation that his decision on the tour must be based only on one fact and that was what is in the best interests of New Zealand. “There is no evidence that I can find,” he said, “that supports in any way the continuation of the tour.”

Frank Corner, secretary of foreign affairs and head of the prime minister’s department, was later to say “the tour did not fit in with Kirk’s view of what New Zealand should do in the world, and what it’s standing would be should the tour proceed.”

Around this time, I was contacted by Bob Scott, an Anglican minister and director of the Wellington Inner City Ministry. He had just met with Norman Kirk. The prime minister’s view, which Kirk wanted relayed to HART, was that the job of the anti-apartheid movement was to be calm and quiet. The government believed that our views were well-known, and the ball game was now being played on a different field – theirs. For the next six weeks, until the tour’s cancellation, Scott acted as go-between for the prime minister and HART.

At the same time, Southern Māori MP, Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan contacted me with a similar message. The prime minister was clearly leaving nothing to chance in getting his message through to us. She assured me that Kirk would act. But the doubts and concerns we had were both real and multiplying. Over the next six weeks, as Scott played out his go-between role, the single question exercising the minds of all in HART’s national leadership was whether or not Scott’s assessment of the prime minister’s intentions could be trusted.

By the beginning of March, those opposed to the tour split into two broad groups. One faction, which aligned with the Labour Party, trusted the prime minister to deliver, and were opposed to HART and CARE being too critical of the government. Others believed that all social democrats were untrustworthy and urged more radical action.

In early March, Bob Scott attended a HART national council meeting. For about an hour, he argued that Kirk could be trusted, and we needed to stay calm. The meeting agreed to what Kirk wanted. We would keep a low profile until the end of the month, but we did so with considerable misgivings. What exactly did “soon, in the soonest sense of soon” mean? It sounded just too glib.

Sharpeville Day, March 21, 1973, saw leafleting, picketing, vigils, a rock concert, marches, rallies and commemorative services throughout the country. We publicised recent messages of support from diverse groups and individuals, including former UN secretary general U Thant and the Anglican Bishop of Woolwich and former MCC cricketer, David Sheppard. The most militant action taken was by members of the New Zealand Seamen’s Union, who stopped work for 24 hours to demonstrate their opposition to apartheid.

After Sharpeville Day, tensions escalated significantly. At the end of March, I was in Dunedin for an anti-apartheid meeting. Scott was also there. I reminded him that our agreement with Kirk was about to expire. Scott indicated that he, too, was concerned with how slow the prime minister was moving. He undertook to contact Kirk.

Towards the end of the first week in April, Scott contacted me. “Early early next week,” I was told. I was fed up. At the beginning of March we had agreed to what the prime minister had asked. We had sat on our hands for a month, and marked time. Now we were being told to wait until mid April. What would we be told then? That the tour was on and that I and others were to be prosecuted? By now, the common view in the HART leadership was that Scott was being taken in by the prime minister, and that we were being taken in by Scott.

It was not just an issue of what the HART leadership was thinking. What about our supporters? We at least knew more or less what was going on between ourselves and the prime minister. Most of our supporters did not. They were becoming increasingly restless. It was easy for some of them to regard the HART leadership as just a bunch of media freaks who had got cold feet.

If we could not control events we at least needed to be singing our own song instead of being in a chorus singing someone else’s tune. A meeting was planned in Wellington for Sunday, April 8. Most of the HART leadership was there. All of us believed, with different degrees of conviction, that the tour was on. In about three months, the Springboks would be here. We needed to start planning and organising for their arrival.

We never got to do that. There was a knock at the door. In walked Bob Scott, who had not been invited to the meeting. A silent sigh ran around the room. How many more days were we going to be told we had to wait? “It’s near its conclusion,” he said. “Just wait a few more days.”

“You keep saying that – a few more days, a few more days,” we replied. Some in the room were adamant one day was a day too long to wait. Others, outside of HART, were clearly thinking the same. That night, a rugby grandstand in Papakura was burnt to the ground.

I sat and listened. I wanted to believe Scott, but ever since he had started acting as go-between, it felt as if we were all players in an updated version of Waiting for Godot. If it came to a vote (which it wouldn’t – most decisions were arrived at through consensus), I would not go with the “just wait a few more days” line.

Towards the end of the meeting, Scott signalled to me as he left the room and I followed. “If I tell you something, will you go back inside and tell them?” he asked. Half a dozen qualified responses flashed through my head. This wasn’t a time for a philosophical discourse on the nature of loyalty, trust or honesty. “No,” I responded, and hoped I would be able to keep my word.

“I spoke with the prime minister yesterday,” he said. “The tour is off.” I must’ve looked unconvinced. “He has written to the Rugby Union requiring the tour be called off.” And then he repeated, “It’s off. The letter has gone to the NZRFU. They have it. Mr Kirk will make the announcement next week.” I believed him.

I went back into the meeting, which was by now grudgingly of the view that we would extend the contract with Kirk and “hold off” for another week. No one asked me what Scott had wanted to tell me but I was asked for my view on how we should proceed. I spoke briefly, positively endorsing the emerging consensus.

I got a ride down to the airport. As we twisted down Mount Victoria, I had great surges of excitement. It was off! The tour was off! The joy was pure, immense, uncomplicated. I felt like a kid at Christmas. The flight back to Christchurch was fairly empty. A flight attendant came and chatted for a few minutes. How was I? Did I think the tour would be called off? I gave the standard response, but inwardly, my smile was so large I feared it might take over my face.

Looking back at the 1970s, the cancellation of the 1973 Springbok tour was part of a brief, exhilarating, period in our politics. If I had to name my favourite year, it would probably be 1973. I was 27, and after 12 years of conservative government, change was on its way.

Trevor Richards was national chairperson of the Halt All Racist Tours movement (HART) from 1969-80, and international secretary from 1980-85.

Search form

- Send Us Your News

- Wedding Guide

- Death Notices

- Privacy Policy

- Drive South

- Media Council Complaints

The forgotten Springbok tour might be the most important

You are not permitted to download, save or email this image. Visit image gallery to purchase the image.

Many people remember the 1981 Springbok tour. Over 56 days, the tour brought the country the closest it had come in the 20th century to civil war.

Fewer people recall the 1976 All Black tour of South Africa. That tour had gone ahead with the blessing and goodwill of the New Zealand government. No other government in the world had offered apartheid South Africa such enthusiastic support.

Countries felt compelled to act. The International Olympic Committee was asked to ban New Zealand from the 1976 Montreal Olympics. The IOC refused.

With the All Blacks still in South Africa, about 30 countries walked out of the Olympics in protest at New Zealand’s presence. The first major boycott of the modern Olympics was caused, not by US-Soviet Cold War rivalries — those boycotts were to come later — but by New Zealand’s support for apartheid.

In 1985, two lawyers brought a case in the High Court which led to an injunction being issued which prevented that year’s All Black tour of South Africa taking place. I am not sure how well remembered that campaign is.

And the cancelled 1973 tour? Today, few know anything much about it. It is the forgotten campaign.

The tours of 1981 and to a lesser extent, 1976, are better recalled, largely because their dreadful outcomes were hard to ignore. The events of 1973 go mostly unnoticed, buried by the dramas of 1976 and 1981. Yet to this activist/student of history — and there’s a potential conflict if ever there was one — the campaign against the 1973 tour was the most significant campaign of them all.

In early 1971 Hart had announced its intention to disrupt the 1973 tour, should it proceed. The reaction of many, especially in provincial and rural New Zealand, was hostile. In February 1973, during a South Island speaking tour, there were foretastes of what was to come in 1981. In Ashburton, about 600 pro-tour supporters had turned out in an effort to prevent me from addressing a meeting. The meeting went ahead, but only after a number of their placards had come crashing down on my head.

In demanding the cancellation of the tour, Hart was openly challenging the values of post World War 2 New Zealand. Then, we were a predominantly rural, male-dominated, conservative society whose Pakeha citizens — well, most of them — believed the country had "the best race relations in the world". Many saw New Zealand as part of a white man’s club which had more or less ruled the world for as long as most people could remember.

These old values were slowly dying, but in 1973 they still possessed a lot of clout. Perhaps no single person better encapsulated them than Tom Pearce, former president of the New Zealand Rugby Football Union and the manager of the 1960 All Blacks in South Africa. In April 1972 he had said "where the white man has been, he has brought law and the establishment of his regime for the benefit of mankind. If these go, we are lost ... They say if we have a Springboks tour, we won’t have a Commonwealth Games — I couldn’t give a damn".

Prime minister Norman Kirk’s decision to stop the 1973 Springboks rugby tour caused an uproar. Organisations supporting the tour threatened "massive retaliation". Rugby Weekly’s front page headline read: "In memory of the grievous harm suffered by a great game at the hands of politicians, international blackmailers and rabble-rousers".

During the 1972 general election, Labour had promised it would not stop the tour. Announcing the abandonment of the tour less than six months later, Kirk said: "I have no doubt that I will be criticised because of the difference in what I said last year, and what I said this year. When it comes to a decision between what I must do in the light of the facts that are put before me in the interest of the country, and a desire to avoid criticism, then I would be failing in my duty if I did not accept the criticism and do what I believe to be right."

Kirk was concerned that if the tour proceeded, African nations would stay away from the 1974 Christchurch Commonwealth Games. He had also received advice from the police that were the tour to proceed, it would engender the greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known. But these were not his major concerns.

Frank Corner, secretary of foreign affairs during Kirk’s prime ministership, has said that "Kirk could see that if he stopped the tour, Labour could lose the next election. But the tour did not fit in with his view of what New Zealand should do in the world, and what its standing would be should it proceed".

It was probably the first time a New Zealand government had sought to change both the way New Zealand viewed itself and the way it wished to present itself to the world.

There would seem to be little doubt that the driving force behind the tour’s abandonment was the prime minister himself. At a Commonwealth finance ministers meeting in Dar es Salaam in September 1973, Bill Rudman was one of a small group of expatriate New Zealanders meeting New Zealand finance minister Bill Rowling. Rudman congratulated Rowling on the government’s decision to stop the Springbok tour. Rowling’s response took Rudman by surprise. That, Rowling said somewhat sniffily, was Mr Kirk’s decision.

Of the four major post-1960 New Zealand battles against apartheid sport — 1973, 1976, 1981 and 1985 — it was the outcome of the 1973 battle which was arguably the most historically significant. It was the cancellation of this tour which heralded the beginning of New Zealand’s gradual shift into a more progressive space.

Related Stories

What to do if shutters close on free speech

Going round a mulberry bush with hospital funding queries

Letters to the Editor: politics, death and tax cuts

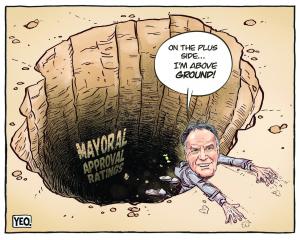

Cartoonist’s view — Yeo

Foundational values struggle to withstand prevailing winds

The end of reefs may not be the end

The meaning of life can be found by those who come and follow

Cartoonist's view - Yeo

Letters to Editor: Corruption, Hamas, George St playground

A new tohu helps to find the path

Gather your own apples? No, you may not

Letters to the Editor: cycle lanes, bus drivers and the arts

Trevor Richards: Fifty years ago, NZ stood up for what was right and stopped a rugby tour to South Africa

Share this article

Reminder, this is a Premium article and requires a subscription to read.

Former Prime Minister Norman Kirk. Photo / NZ Herald Archives

Fifty years ago today, Labour Prime Minister Norman Kirk stopped the 1973 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand.

Frank Corner, Secretary of Foreign Affairs during Kirk’s Prime Ministership, has said that “Kirk could see that if he stopped the tour, he could lose the next election. But the tour did not fit in with his view of what New Zealand should do in the world, and what its standing would be should it proceed.”

It was probably the first time that a New Zealand government had sought to change both the way New Zealand viewed itself and the way it wished to present itself to the world. It was a brave decision, and it engendered strong opposition, much of it absurd.

Jock Wells, the President of the Wellington Rugby Football Union called the tour’s cancellation “the worst news I have heard since 34 years ago when Chamberlain stated that England was at war with Germany”.

Labour did lose the next election.

The incoming National government openly welcomed a resumption of rugby contact with racially-selected South African teams. Prime Minister Muldoon’s enthusiastic support for the 1976 All Black tour of South Africa resulted in around 30 countries, mostly African, boycotting the Montreal Olympics in opposition to New Zealand’s presence.

In 1981, the Springbok tour of New Zealand brought the country the closest it had come in the 20th century to civil war.

Kirk’s decision had been the right one.

The 1976 and ‘81 tours are better remembered than the cancelled 1973 tour, probably because of their disastrous outcomes.

Yet in one major respect, it was the most important of the three, as it was the 1973 decision which heralded the beginning of a seismic shift in New Zealand society.

In the years following World War II, the country was largely rural, male-dominated and conservative. Pakeha citizens - well, most of them - believed that New Zealand had “the best race relations in the world”.

Abortion and homosexuality were illegal. Internationally, we identified with Empire. We were a country whose cultural landscape was dominated by rugby, racing and beer.

Until the mid-1960s, short back and sides were the universal hairstyle for men, and ladies were always expected to “bring a plate”. Within the space of a little more than two decades, all this changed.

By the time the fourth Labour government left office in 1990, we recognised Māori as tangata whenua and saw ourselves more as a South Pacific/Asian nation rather than as a territory of Empire. We were proudly anti-nuclear and anti-apartheid.

On abortion, New Zealand was pro-choice. Old laws discriminating against homosexuals had been repealed. These changes did not occur overnight.

It was a long and gradual process, but it had to begin somewhere, and if one was to put a date on when this change started to gather real momentum, it would be the election of the third Labour government at the end of 1972.

Two months after the tour’s cancellation, the HMNZS Otago sailed to Mururoa to protest against French nuclear testing in the Pacific. Prime Minister Norman Kirk told the crew of the Otago that they were to be “silent witness[es] with the power to bring alive the conscience of the world”.

In the same year, the Labour Government announced that from 1974, February 6 would be a national holiday known as New Zealand Day. With the exception of the 1940 centennial celebrations, this day had barely registered with most New Zealanders. A public holiday only in Northland, it was regarded as no more than a local event.

Kirk sought to change that, to make the day a celebration of New Zealand’s multiculturalism.

In March 1974, Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere visited New Zealand, the first time an African head of State had set foot on New Zealand soil.

In 1975 the Labour government set up the Waitangi Tribunal, providing a legal framework for the investigation and resolution of Māori Treaty claims. The third Labour Government was critical in initiating a number of the changes which laid the foundation for New Zealand’s shift into a more progressive social and political space, both nationally and internationally.

The cancellation of the 1973 Springbok tour had been one of the first steps in that process.

And the impact of the tour’s cancellation in South Africa? In 1995, Nelson Mandela told Norman Kirk’s son Phillip, that learning of the 1973 tour’s cancellation from his prison cell was the first time he thought that apartheid might actually end in his lifetime.

- Trevor Richards was the National Chairperson of the Halt All Racist Tours movement (HART) from 1969-80, and International Secretary from 1980-85

Latest from New Zealand

Canny View: Do you want to be rich or wealthy?

OPINION: Having a large income does not guarantee financial stability.

Test, fail, get a free critique: Woman teaching driving lessons says she's lost 75% of her customers

The battle for Hawke's Bay Tourism: Who should fund it, and what would happen if it disappeared?

'Pretty special': Hawke's Bay short film wins big overseas

The people who pick up the pieces

Quality worth making room for

What we tell ourselves about the Springbok tour

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

September 12, 1981 has come to represent the crescendo of the ill-fated Springbok tour. On this day 40 years ago, around 2000 protestors descended on a fortress-like barbed wire-clad Eden Park as the Springboks and All Blacks played a series-deciding final test. Inside the stadium, a light aircraft made low flying swoops over the ground throughout the game, sometimes barely making it over the goalposts, dropping bags of flour onto the field and players. With the Hamilton pitch invasion, the ‘flour-bomb test’ has endured in the public conscience.

Amid a raft of commemorations for the tour’s 40th anniversary, it is worth considering how this day will be remembered and what this tells us about national history making. Most commemorators will likely emphasise the unscripted drama that unfolded inside the stadium, in the skies above it, and in the streets outside. Some will recall the match as riveting, which among the flour bombs ran 10 minutes overtime and took an Alan Hewson penalty to win the match and series for the All Blacks. Others will raise an incident where a group of peaceful protesters outside Eden Park dressed as clowns were senselessly beaten by police. Fewer still will recall that on a tour shrouded in apartheid controversies, the final test was scheduled on the fourth anniversary of the death of activist and founder of South Africa’s Black Consciousness movement Steve Biko, who was murdered while in police custody by white officers.

But the contemporary representation of 1981 as an anti-apartheid endeavour also forgets that the anti-tour movement was as much a critique of New Zealand society.

But likely none will consider that the stories they contemporarily tell about the Springbok tour are as much a product of the time during which they are produced as they are an attempt to recall the past. For in the process of turning the unobservable past into a comprehensible history for the present, we inevitably look at the past through the ideological lens of contemporary values. And as values and the present change, so does the way we evaluated, narrate, and historicise the past. While the past is unchangeable, history is always shifting and evolving as certain parts of the past become emphasised, while other, less palatable parts are forgotten based on what is valued in the present. Exploring what is told about the Springbok tour at a given historical moment can tell us a lot about the social values of the time.

The contemporary emphasis on New Zealand as a bicultural, anti-racist society has meant that 1981 is most commonly ‘remembered’ as the country’s struggle against the horrifically racist apartheid system. But this obscures and forgets the more unpalatable reality that there was substantial support for the tour among many New Zealanders.

Stadiums were sold out and attracted more than three-quarters of the country’s television audience. Few will recall that the predominantly white Springbok team (one player and one manager were not white) received scores of letters from New Zealanders welcoming and supporting them, or that New Zealand’s far right groups, who sought closer relationships between white people across the two countries, enjoyed perhaps their biggest influx of support and highest public profile when rugby ties with South Africa became contested.

Rather than accepting historical accounts at face value, it is important to ask why some parts rather than others endure and come to represent what we ‘know’ about the past.

But the contemporary representation of 1981 as an anti-apartheid endeavour also forgets that the anti-tour movement was as much a critique of New Zealand society. Journalist and activist Geoff Chapple recalled in 1984 that the tour had “grown far beyond the original anti-apartheid issue. It now defined a whole belief system about what was right and wrong about New Zealand itself”.

Apartheid may have catalysed the movement, but the anti-tour protests also became an outlet for many of the domestic social tensions of the previous decades. Protesters raised their frustration at: a conservative government which deported Pacific Island ‘overstayers’, annexed Māori lands but encouraged the immigration of white South Africans; a national sport that promoted restrictive gender roles, toxic patriarchal masculinity, excessive consumption of alcohol and a culture of violence; and institutionalised racism which many Māori linked to the experiences of black South Africans.

Emphasising 1981 as primarily an anti-apartheid struggle obscures the complexity of the anti-tour campaign. It serves largely to construct New Zealand society in a favourable way which forgets some of the unpalatable realities that accompanied the tour.

How the Springbok tour has been understood by New Zealanders has evolved over 40 years (and will continue to evolve) in response to changing material conditions. By treating histories of 1981 as a kaleidoscope of partial, contested and selective narratives which seek to impose particular meaning on the past, we can learn much about the purpose of their creators, the eras in which they were created, and the way we make meaning as a nation more broadly.

Dr Sebastian JS Potgieter

Dr Sebastian JS Potgieter is a teaching fellow at the University of Otago’s School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences. More by Dr Sebastian JS Potgieter

Leave a comment

Join the Conversation Subscribe to Newsroom Pro to unlock commenting on articles. Start your 14-day free trial now or sign in . Please note: All commenters must display their full name to have comments approved. Click here for our full community rules.

Start your day with a curation of our top stories in your inbox.

We've recently sent you an authentication link. Please, check your inbox!

Sign in with a password below, or sign in using your email .

Get a code sent to your email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

Enter the code you received via email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

Subscribe to our newsletters:

Sign in with your email

Lost your password?

Try a different email

Send another code

Sign in with a password

I agree to Newsroom's Terms and Conditions

The Springbok Tour

A DigitalNZ Story by Hana McIntyre

A digitalNZ story by Hana McIntyre

The springbok tour of the 1980’s was the largest civil disturbance New Zealand had seen in thirty years. The whole of New Zealand was divided over the tour, this division of the country lasted over fifty days. The Springbok tour was a real factor in the way New Zealand grew as a county. The outcomes that arose from the tour has led New Zealand to find and express our identity as people and as nation.

Maori take a stand

A group of maori protesters stand together with helmets on as police with baton smarch behind them.

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The beginning

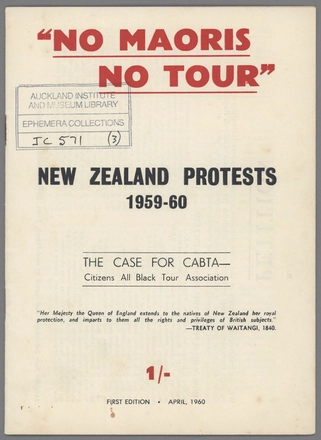

This pamphlet was given out in the 1960's in an effort to have maori included in the tour.

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

Together as a nation

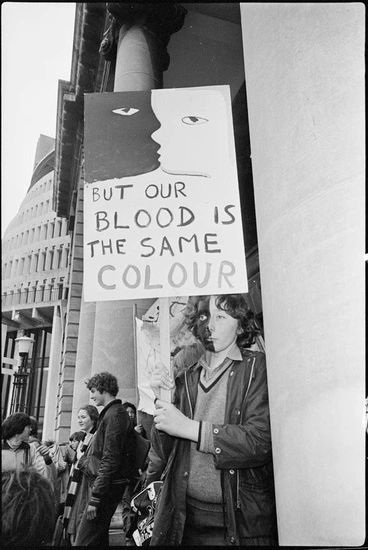

All people of NZ came together to protest the tour, despite the debate on NZ racism, people of all backgrounds joined.

The tour was a useful tool as it helped to kick start the discussion of New Zealand's identity. For many decades New Zealand was in a limbo, we had the fundamentals of a culture events, people and objects all people could relate to. This is prominent in the source of the tour, rugby. Such a staple in ‘kiwi culture’, rugby is a thing everybody could enjoy no matter their race, age or gender. Rugby was a nationwide spot that the rest of the world knew as kiwi culture. However, this all changed when the announcement was made that the All Black would be taking am ‘all white’ team to play the springbok tour in South Africa.

Police resistance

Police and protesters in 1981

Children joined the fight

The tour did not only see adults who fought and protested, but it also saw young children protesting with their familie.

NZ Police 1981

Police where given 'night sticks' to keep protesters under control.

A nation always slightly confused about where the line of culture stood between Maori natives and the pakeha. This was an event that would change the way Maori people saw themselves and their culture within New Zealand's culture. People started to stand against the tour, peaceful marches where organized, rallies with children were held. People even boycotted games in an effort to bring awareness to the fact that an ‘all white’ team was unacceptable in a country where its native people would not be included in such a prominent activity that defined the nations sporting culture.

The riot squad posing for a picture in 1981. They where a step up for NZ police and a shock for NZ people.

Peaceful protesters fight against the Springbok tour and for the recognition of NZ's own faults.

The uncle of the of the captain of the NZ Maori team stood with the NZ Police in napier in 1981

Alexander Turnbull Library

Maori and Pacifica people started to express their identities more, “people started to realize you can’t protest against racism 6,000 miles away when it’s right here in your country” - John Minto This quote from John Minto clearly sums up the thoughts of many people at the time. How are we as a country supposed to find a collective identity if we cannot even see the own blatant racism that happens daily in New Zealand.

The New Zealand Police force are not known to be aggressive or violent. However, the springbok tour bought out the worst in the Police of New Zealand. On the night of the 21st of July 1981 Police brought down their ‘nightsticks’ onto a crowd protester’s who refused to ‘halt’, leaving many people with injuries. This is a prominent event within the Springbok tour. However, New Zealand does not let this define our police nor do we let it impact our culture in a manner where we lost all of the good relations between police and the New Zealand public. This however did tend to complicate the traditional depictions of kiwi culture, as we now had to reinvent the culture of NZ Police.

Public opinions

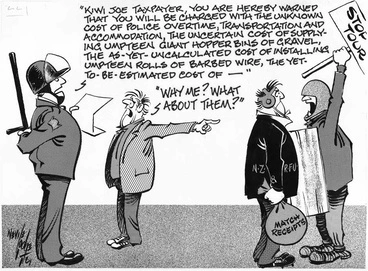

The tour effected everyone, the people who had a voice in society often used it in many ways this time a comic was drawn

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

![[Springbok Tour - Auckland street protest] Image: [Springbok Tour - Auckland street protest]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2Fd3085a739ec91232075a008722345e591fec81aa%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

Police vs Civilians

The tour of 1981 hindered civilians relations with NZ Police.

Police force

Police men and women get ready to face another encounter with protesters.

The tour tells us many things about how kiwis expressed their identities in the past. New Zealand has never been a violent country, new Zealanders have tended to express and convey their feeling through actions and speech. This is a part of kiwi identity in itself, we don’t identify as aggressive people or a nation who is an aggressive world party. This alone reinforces the idea of traditional ‘Kiwi Culture’. We are known as a people of fierce warriors but also known as a nation of respect and understanding.

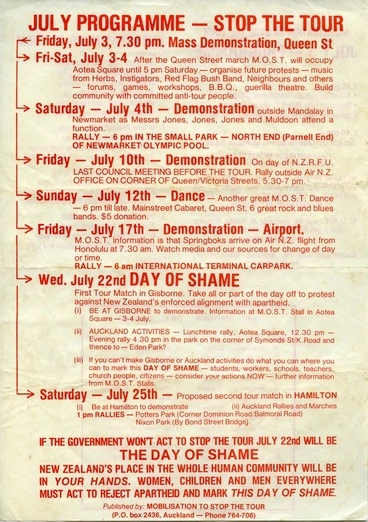

Springbok Tour protest programme

School children protesting, 1981 Springbok tour

Furthermore, this event deepened our Maori populations identity within New Zealand. The tour made many people realize how poorly our own native people has been treated within our society. This was a catalyst for the change that we see today. Over the past thirty years New Zealand’s identity has become much more inclusive of Maori and all their traditional customs. Maori have become a large part of Kiwi identity and a larger part of ‘kiwi culture’. While the tour was a confusing time for many New Zealanders its consequence of the highlighting of Maori injustice helped to confirm what we see now as ‘traditional kiwi culture’.

New Zealand has always been a proud country, we like to think that we have always had each other's backs and continue to do so even through the toughest of times. The springbok tour was a major exception to this belief. However, this tour ended up adding value and lessons to which became some of New Zealand's most important values and morals. These have now become what we call ‘Kiwi culture’.

Peaceful Protest 1981

The people of New Zealand banded together for peaceful protests against the tour in Wellington 1981

Bibliography

References:

M. (2014, August 5). 1981 Springbok tour. Retrieved from https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/1981-springbok-tour

T. (2006, July 16). Springbok Tour Protests 'Good For Maori'. Retrieved from http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO0607/S00145.htm

M. (2018, July 20). Police baton anti-tour protesters outside Parliament. Retrieved from https://nzhistory.govt.nz/police-baton-anti-springbok-tour-protestors-near-parliamentv

Listener, T. (2016, November 21). Inside the 1981 Springbok tour. Retrieved from https://www.noted.co.nz/archive/listener-nz-2011/inside-the-1981-springbok-tour/

Wellington City Libraries. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.wcl.govt.nz/heritage/tour.html

Roughan, J. (2017, August 25). NZ memories: Protests during the Springboks tour. Retrieved from https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10830511

http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/collection/object/am_library-ephemera-11756

https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22905580?search%5Bi%5D%5Bcollection%5D=Dominion+post+%28Newspaper%29%3A+Photographic+negatives+and+prints+of+the+Evening+Post+and+Dominion+newspapers&search%5Bi%5D%5Bprimary_collection%5D=TAPUHI&search%5Bi%5D%5Bsubject%5D=Police&search%5Bpath%5D=items

New Zealanders protest against Springbok rugby tour, 1981

Time period, location description, methods in 1st segment, methods in 2nd segment, methods in 3rd segment, methods in 4th segment, methods in 5th segment, methods in 6th segment, additional methods (timing unknown), segment length, external allies, involvement of social elites, nonviolent responses of opponent, campaigner violence, repressive violence, classification, group characterization, groups in 1st segment, success in achieving specific demands/goals, total points, notes on outcomes, database narrative.

Halt All Racist Tours (HART) was organized in New Zealand in 1969 to protest rugby tours to and from South Africa. Their first protest, in 1970, was intended to prevent the All Blacks, New Zealand’s flagship rugby squad, from playing in South Africa, unless the Apartheid regime would accept a mixed-race team. South Africa relented, and an integrated All Black team toured the country.

Two years later, the Springboks arranged a tour of New Zealand. HART held intensive planning meetings, and, after laying out their nonviolent protest strategies to the New Zealand security director, he was forced to recommend to the government that the Springboks not be allowed in the country. Prime Minister Kirk, though he had promised not to interfere with the tour during his election campaign, canceled the Springbok’s visit, citing what he predicted would be the “greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known.”

HART remained active in the anti-apartheid community, continuing to protest the Springboks, and helping to organize a boycott of the 1976 Montreal Olympics. The International Olympic Committee had not banned New Zealand after the All Blacks had toured South Africa, and many African countries saw this failure as a tacit endorsement of Apartheid. In 1980, New Zealand again attempted to bring the Springboks to New Zealand.

The Springboks arrived on July 19, 1981. Though they were officially welcomed by the New Zealand government, there was a sense of dread and anticipation that surrounded their arrival – perhaps, some thought, the 1981 tour should have been cancelled like the tour in 1972 was. The government officials could not anticipate, however, that the country was about to fall into “near-civil war.” In response to HART, pro-rugby groups like Stop Politics in Rugby (SPIR) organized in an effort to help the Springbok’s tour succeed. Both sides tended to be easily identified by armbands that made their affiliation clear. In particular, HART activists wore their armbands for the entire length of the tour, subjecting themselves to constant ridicule and the threat of violence, despite their commitment to nonviolent protest only.

The Springboks played their first game on July 22 in Gisborne. An anti-Springbok rally took place that day, near the rugby pitch. When the campaigners arrived at the arena, they were confronted by pro-rugby demonstrators. Because Gisborne, like most cities in New Zealand, was close-knit, demonstrators on both sides knew each other, and were not afraid to call each other out for supporting the wrong side, whichever they believed that was. The pro-rugby demonstrators did not restrict themselves to words, even throwing stones at the other side. The anti-Springbok protesters could not stop the match that day. Though they were able to break through the perimeter fence, and engage the pro-tour demonstrators face to face, they were prevented from occupying the field. Though both sides reported that they were uneasy with the clashes between fellow New Zealanders, neither side was easily swayed.

Three days later, the Springboks were scheduled to play in Hamilton. Anti-Springbok planners had circulated a strategy that would hopefully allow them to tear down the fence, invade the field, and disrupt the match. Protesters had also secured more than 200 official tickets to the match, to make sure that their presence was felt, even in the event that they could not storm the pitch. Despite the presence of more than 500 police officers and a sizable pro-rugby contingent, the anti-Springbok march would prove unstoppable. 5000 anti-Springbok protesters descended upon the Hamilton pitch, and more than 300 made it onto the field, forcing a match cancellation. Protesters chanted that the whole world was watching. Many of the demonstrators were arrested, and those on the pitch endured a constant bombardment of bottles and other objects from rugby fans in the stands. This entire situation was captured on live TV and shown around the world.

With tensions in New Zealand reaching astronomical proportions, the Springboks were next scheduled to play four days later, on July 29. The anti-Springbok protesters were largely absent from the match, but had instead planned a march on the South African consulate in Wellington, New Zealand. Despite police declaring that a march was not permitted, the protesters marched right up to the police line on Molesworth Street. The police began to stop the marchers with their batons, violently forcing them away from the consulate building. The marchers, stunned and bloodied, turned towards the police station, chanting “Shame, shame, shame.” When they arrived, the accosted marchers pressed assault charges on the police that had attacked them. Though the charges were dismissed, the policing of the tour protests had taken a turn for the worse. From this point on, protesters were careful to carry shields and wear crash helmets in order to protect themselves from attacks.

Protests would continue for the entire length of the Springbok’s stay in New Zealand. Only one more match was cancelled, in Timaru. However, there were a few more notable encounters. In Christchurch, on August 15, protesters failed to occupy the pitch in time for the game to be cancelled. The police cordon around the arena held, and several observers believe that the police saved the lives of many protesters. The attacks of rugby supporters were growing more and more violent, The Christchurch incident was characterized by flying blocks of cement and full beer bottles. Had the anti-Bok protesters succeeded in reaching the field, the attacks would certainly have been even more dangerous.

The final match of the tour was in Auckland on September 12. Not only was the match important as a final chance for protesters to demonstrate their opposition to the Springboks, it was the deciding third meeting between the Springboks and the All Blacks. Doug Rollerson of the 1981 All Blacks recalled that it seemed very important for the All Blacks to win the match, to show that a mixed team was superior to the segregated Springbok side. When the All Blacks won, the sense of victory in New Zealand was similar to the US victory over the Soviet Union in 1980 – the triumph of righteousness over the evil empire. However, for most observers around the world, the off-field events were far more important. Though the protesters were generally non-violent, there were many others that joined in the marches – HART characterized them as opportunists that simply wanted to fight with police. Though eruptions of violence had taken place throughout the campaign, they were largely viewed by the protesters as third-party actions, and HART consistently distanced themselves from violent attacks. More memorably, Max Jones and Grant Cole commandeered a prop plane, and proceeded to drop flares and flour bombs on the pitch during play in an attempt to stop the game. Though the game continued, the actions of the protesters were again the primary news story in New Zealand and throughout the world.

Though the anti-Springbok protests were largely unsuccessful in that the vast majority of the planned contests took place, they were able to raise an incredible amount of awareness for the anti-Apartheid movement. Nelson Mandela recalled that when the game in Hamilton was cancelled, it was “as if the sun had come out.” HART would continue protesting until the fall of the Apartheid regime.

Influenced and influenced by anti-Springbok protests in other countries like Australia, Britain (see "Australians campaign against South African rugby tour in protest of apartheid, 1971" and "British Citizens Protest South African Sports Tours (Stop the Seventy Tour), 1969-1970") (1,2).

This campaign was also influenced by the New Zealand Waterfront Strike (1951) (1).

Additional Notes

Name of researcher, and date dd/mm/yyyy.

Navigation for News Categories

Documents reveal political cost for new zealand of hosting 1981 springboks tour.

Declassified documents released by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs show the political ramifications New Zealand faced for hosting the 1981 Springboks Tour.

There were protests where ever the Springboks went during their 1981 tour of New Zealand. Photo: Photosport

Nigeria led the backlash alongside other West African nations, appalled New Zealand would allow South Africa to tour New Zealand and play the All Blacks while South Africa was implementing its apartheid policy.

In a statement, sent directly to Commonwealth allies and the New Zealand government, Nigeria said New Zealand was breaching the Gleneagles Agreement, which was set up to discourage sporting competition with South Africa during apartheid.

The Nigerian government said if the tour went ahead it would seek strong sanctions against New Zealand, and would assure there were mass boycotts of all events in which New Zealand participated.

In an internal memo that has only now been released, then prime minister Rob Muldoon was fuming at Nigeria's government.

"I have told the Commonwealth Secretary-General that firstly, if this action proceeds I will recommend to my colleagues in the government party that New Zealand withdraw from the Gleneagles Agreement as other Commonwealth countries are prepared to distort its meaning to our disadvantage," he wrote.

"Secondly, I have in any case requested the Secretary-General to place the question of human rights on the agenda for the Melbourne heads of government meeting. There I propose to initiate an examination of New Zealand's record and place it alongside that of such countries as may see themselves as our accusers in this matter."

He said New Zealand's opposition to apartheid was clear, and went on to write: "We will not be labelled as an international pariah simply because we uphold the principle of freedom of association and freedom from interference for our sportsmen and sporting bodies."

Stu Wilson in action against the Springboks during the South Africa tour of New Zealand 1981. Photo: Photosport NZ

Regardless of sporting boycotts, the Springboks Tour had very real political consequences on a global stage.

In a briefing regarding fisheries, it is noted that Nigeria and West Africa in general were major importers of New Zealand's white fish, but that had stopped as a result of the tour.

"In each of the last two years, bulk shipments of barracouta have been made to Nigeria. Nigeria, and West Africa in general, have a large demand for fish and an increasing ability, in some cases, to pay for imports," the report said.

"Without these bulk shipments, intolerable pressure would have been placed on traditional outlets and a drop in price unavoidable. With the inability to make another sale to West Africa, this is now happening."

The report said the fisheries industry had to develop new markets as a result, and was exploring Egypt as a potential destination for the bulk of barracouta that needed a foreign buyer.

Russia and Eastern Europe were also listed as a possibility, but Egypt was the top priority.

Protestors interrupt one of the Springboks games. Photo: Photosport

Meanwhile, the government's relationship with the New Zealand Rugby Union had also soured.

In a letter from the New Zealand Ambassador to Vienna to the Secretary of Foreign Affairs, they talk about the All Blacks upcoming tour to Romania.

"Normally, and especially as this is the All Blacks' first visit in Socialist East Europe (where life has its peculiarities and risks, not least those of a security nature) the Vienna Embassy would have felt it advisable, in the case of such a sizeable group of New Zealand citizens, to arrange in some way to have an officer from Vienna on the spot," the letter reads.

"In the ordinary way, too, I would have felt it appropriate to go to Bucharest for the All Black test there, in order, particularly, to give them and their hosts some form of hospitality as a measure of quid pro quo on New Zealand's behalf.

"Obviously this sort of traditional scenario will now need reviewing, depending on what is the final outcome of the current Springbok tour of New Zealand, and what broad attitude is thereafter taken by our Government to the NZRFU."

The newly released documents are available for viewing at Archives New Zealand in Wellington.

Copyright © 2021 , Radio New Zealand

Related Stories

The last time a rugby game got played in an empty stadium.

Super Rugby Aotearoa will be played in empty stadiums - the last time that happened was in 1981 and involved New Zealand's fiercest rivals, writes Jamie Wall .

A history of cancelled rugby matches

In light of the two cancelled Rugby World Cup matches, including this weekend's All Blacks-Italy match, RNZ has compiled a list of other games to be canned.

Australia considered option of NZ Games ban

Australian cabinet papers from 30 years ago reveal that concern about the 1981 Springbok tour was so high, it jeopardised New Zealand's participation at the Commonwealth Games the following year.

New Zealand

- 'Data is the new oil': Call to save jobs of data security guards

- More than half of workers report severe burnout, driven by job insecurity

- One seriously injured after reported assault in Bayfair Shopping Centre

- Ex-cop and convicted rapist Brad Shipton has died

- Sea change: SuperGold cards to be allowed on Auckland ferry

- Public health expert urges govt to focus on disease prevention

Get the RNZ app

for ad-free news and current affairs

Top News stories

- Former Trump aide Hope Hicks testifies he told her to deny Stormy Daniels affair

- Blues stay in touch with Super Rugby leaders after win over Rebels

New Zealand RSS

Follow RNZ News

IMAGES

COMMENTS

In July 1969 HART (Halt All Racist Tours) was founded by University of Auckland students with the specific aim of opposing sporting contact with South Africa. With a Springbok tour to New Zealand scheduled for 1973, the issue was to become increasingly politicised. Kirk and the Springbok issue. In the run-up to the 1972 election, Norman Kirk ...

Fifty years ago a rugby tour of New Zealand was scheduled. After loud and often rowdy protest against it, the tour was called off. Trevor Richards remembers the cancelled Springbok Tour of 1973 ...

10 April 1973. Prime Minister Norman Kirk informed the New Zealand Rugby Football Union (NZRFU) that the government saw 'no alternative' to a 'postponement' of the planned tour by the South African Springboks. This decision followed advice from the Police that if the tour went ahead it would 'engender the greatest eruption of violence ...

Today, few know anything much about it. It is the forgotten campaign. The tours of 1981 and to a lesser extent, 1976, are better recalled, largely because their dreadful outcomes were hard to ignore. The events of 1973 go mostly unnoticed, buried by the dramas of 1976 and 1981. Yet to this activist/student of history — and there's a ...

The last apartheid-era Springbok rugby team landed in New Zealand 40 years ago, on July 19 1981. In the 500 days leading up to the South African team's arrival the anti-tour movement predicted ...

Fifty years ago today, Labour Prime Minister Norman Kirk stopped the 1973 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand. Frank Corner, Secretary of Foreign Affairs during Kirk's Prime Ministership, ...

1973 springbok tour to nz cancelled Kirk argued that the country should not be put through the social turmoil that was likely to result if the tour proceeded. Plus, he didn't want to risk a boycott the 1974 Commonwealth Games to be hosted at QEII in Christchurch.

Fifty years ago this month, Labour prime minister Norman Kirk announced the cancellation of the scheduled 1973 Springbok tour of New Zealand. Halt All Racist Tours movement (Hart) leader Trevor Richards assesses the significance of the tour's cancellation ... And the cancelled 1973 tour? Today, few know anything much about it. It is the ...

Police officers guarding a barbed wire perimeter around Eden Park near Kingsland railway station. The 1981 South African rugby tour (known in New Zealand as the Springbok Tour, and in South Africa as the Rebel Tour) polarised opinions and inspired widespread protests across New Zealand. The controversy also extended to the United States, where ...

In 1981 the Springbok rugby team toured New Zealand which led to public protests. Those against the tour objected to South Africa's apartheid policies, whilst those supportive of the tour thought politics and sport shouldn't mix. The game against Waikato at Hamilton's Rugby Park on 25 July was called off when several hundred anti-tour ...

September 12, 1981 has come to represent the crescendo of the ill-fated Springbok tour. On this day 40 years ago, around 2000 protestors descended on a fortress-like barbed wire-clad Eden Park as the Springboks and All Blacks played a series-deciding final test. Inside the stadium, a light aircraft made low flying swoops over the ground ...

From Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage: Keeping sport and politics separate was becoming increasingly difficult. In July 1969 HART (Halt All Racist Tours) was founded by University of Auckland students with the specific aim of opposing sporting contact with South Africa.

Forty-five years ago this week, debate was raging in New Zealand over something that never happened - the 1973 Springbok tour of New Zealand, which had just been cancelled by the Labour government of Prime Minister Norman Kirk.

The Springbok Tour. The springbok tour of the 1980's was the largest civil disturbance New Zealand had seen in thirty years. The whole of New Zealand was divided over the tour, this division of the country lasted over fifty days. The Springbok tour was a real factor in the way New Zealand grew as a county. The outcomes that arose from the ...

Cancelation of 1973 tour. A key cause which resulted in the 1981 Springbok tour protests was the cancellation of the 1973 tour. Throughout the Springbok tours of Britain and Australia in 1970 and 1971, there were a number of strong and somewhat violent protests, culminating in a sense of unrest in both South Africa and their host countries.

1981 Springbok tour. For 56 days in July, August and September 1981, New Zealanders were divided against each other in the largest civil disturbance seen since the 1951 waterfront dispute. The cause of this was the visit of the South African rugby team - the Springboks. Read the full article.

Read a story about the 1981 Springboks rugby tour. The 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand caused social ruptures within communities and families across the country. With the National government backing the tour, protests against apartheid sport turned into confrontations with both police and pro-tour rugby fans — on marches and at matches.

In 1980, New Zealand again attempted to bring the Springboks to New Zealand. The Springboks arrived on July 19, 1981. Though they were officially welcomed by the New Zealand government, there was a sense of dread and anticipation that surrounded their arrival - perhaps, some thought, the 1981 tour should have been cancelled like the tour in ...

"Obviously this sort of traditional scenario will now need reviewing, depending on what is the final outcome of the current Springbok tour of New Zealand, and what broad attitude is thereafter taken by our Government to the NZRFU." The newly released documents are available for viewing at Archives New Zealand in Wellington.

Date: 1973 From: Lodge, Nevile Sidney 1918-1989 :[Archive of original cartoons for the Evening Post and Sports Post, 1941 to 1988] Reference: B-134-409 Description: This cartoon features the proposed 1973 Springbok rugby tour and features Prime Minister Kirk anxiously looking up at a rugby ball labelled 1973 Springbok Tour. Attached to the ball is a label saying 'Still On - NZRFU'.

The cancelled Springbok tour of 1973 Longform thespinoff.co.nz Open. Archived post. New comments cannot be posted and votes cannot be cast. ... Best. Top. New. Controversial. Old. Q&A. Johnny_Monkee • Good article. I was not aware that there even was a planned tour then. What was said then was fairly prescient of events that were to occur in ...