Cessna 177B Cardinal Single-engine four-seat tricycle-gear cantilever high-wing cabin monoplane, U.S.A.

Archive Photos 1

1977 Cessna 177B Cardinal (N20124, s/n 17702631) at the 2009 Cable Air Show, Cable Airport, Upland, CA (Photos by John Shupek)

- Cessna 177B Cardinal

- Role: Light utility aircraft

- Manufacturer: Cessna Aircraft Company

- First flight: 1967

- Introduced: 1968

- Produced: 1968-1978

- Number built: 4,295

- Unit cost: USD $27,250 (new aircraft in 1976)

The Cessna 177 Cardinal is a light, high-wing general aviation aircraft that was intended to replace Cessna’s 172 Skyhawk. First announced in 1967, it was produced from 1968 to 1978.

Cessna 177 Development

The Cessna 177 was designed in the mid-1960s when the engineers at Cessna were asked to create a "futuristic 1970s successor to the Cessna 172". The resulting aircraft featured newer technology such as a cantilever wing with a laminar flow airfoil. The Cessna 177 is the only production high-wing Single-engine Cessna since the Cessna 190/195 series to have both fixed landing gear and a cantilever wing without strut bracing.

The 1968 Cessna Model 177 was introduced in late 1967 with a 150-hp (112 kW) engine. One of the design goals of this Cessna 172 replacement was to allow the pilot an unobstructed view when making a turn. In the Cessna 172 the pilot sits under the wing and when the wing is lowered to begin a turn that wing blocks the pilot’s view of where the turn will lead to. The engineers resolved this problem by placing the pilot forward of the wing’s leading edge, but that led to a too-far-forward center of gravity.

This problem was partially counteracted by the decision to use the significantly lighter Lycoming O-320 four-cylinder engine in place of the six-cylinder O-300 Continental used on the 172. The forward CG situation still existed even with the lighter engine, so a stabilator was chosen, to provide sufficient elevator control authority at low Airspeeds.

The Cessna 177 design was intended to be a replacement for the Cessna 172, which was to be discontinued after introduction of the new aircraft. The new design was originally to be called the Cessna 172J (to follow the 1968 model 172I). However, as the time came to make the transition, there was considerable resistance to the replacement of the Cessna 172 from the company’s Marketing Division. The 1969 Cessna 172 jumped to the designator Cessna 172K -- there is no Cessna 172J.

Performance and Handling Problems

The stabilator of the Cessna 177 was not fully counterbalanced (only 75% counterweighted, to save about 4 pounds of weight). This caused a phenomenon called pilot-induced oscillation (PIO), as the pilot tried to correct a nose-high or nose-low attitude with out-of-sync elevator inputs which exacerbated the undesirable attitude.

The NACA 65A015 airfoil used on the Cessna 177 was chosen for its laminar-flow characteristics. This airfoil has a much higher drag at low Airspeeds than the NACA 2412 airfoil used on the Cessna 172, so in order to obtain a positive rate of climb the pilot had to use a higher climb Airspeed than was common in the Cessna 172.

Soon after delivery to customers was commenced reported incidents of Pilot-induced oscillation became so alarming that the factory initiated a priority program to eliminate the problem. The solution, which was provided to all aircraft already delivered at no cost, was known as Operation "Cardinal Rule" and included a series of 23 inspection, installation, and modification instructions.

This Service Letter, SE68-14, consisted of modifying the stabilator to install slots just behind the leading edge (to delay the onset of stabilator stall) and installing full counterbalance (11 pounds versus the original 7 pounds) on the stabilator to eliminate the PIO problem. The gearing ratio on the anti-servo tab (at the trailing edge of the stabilator) was also modified.

Initial Cessna 177 Sales

Though the Cessna 177 initially sold well as factory-authorized dealers filled their previously-agreed upon marketing commitments, overall the sales did not meet company expectations. Due to the reluctance on the part of the factory’s Marketing Division, Cessna decided to continue production of the Cessna 172 for at least one more year, so that the relative market strengths of both aircraft could be better evaluated. This decision to continue to produce the Cessna 172 meant that the Cessna 172 production line had to be reactivated and a last-minute decision about engines was needed. The long-term contract for Continental O-300 engines had been canceled and a large contract (5,000 units) had been placed with Lycoming for O-320 engines. Fortunately, the O-320 could be installed in the Cessna 172 with few problems, so the 1968 Model Cessna 172I was offered with an increase of 5 horsepower (4 kW), alongside the new aircraft.

The new design was named the Cessna 177 and given the name "Cardinal" when it was equipped with the optional-equipment package at the last minute. The Cessna 177, with its 150-hp (112 kW) powerplant, was considered "underpowered", even though it had more power than the 145-hp (108 kW) Cessna 172. The Cessna 177 did not climb as quickly as the Cessna 172I at the same indicated Airspeed and its cruise speed was less than the Cessna 172I even with its apparently sleeker silhouette and the same 150-hp (110 kW) engine installed.

Cessna 177A

Recognizing that the aircraft was underpowered, Cessna introduced the Cessna 177A in 1969. The revision featured a 180-hp (135 kW) version of the same four-cylinder Lycoming used in the Cessna 177, moving the design’s price and role somewhere between that of the Cessna 172 and Cessna 182. The additional power improved cruise speed by 11 knots (20 km/h). The 177A also included the fiberglass, downward-shaped, conical wing tips that had been introduced on the Cessna 172 of the same year.

Cessna 177B

Cessna 177RG Cardinal RG

The final aircraft in the Cessna 177 line was the retractable-gear Cessna 177RG, which Cessna began producing in 1971 as a direct competitor to the Piper PA-28-200R Cherokee Arrow and Beechcraft Sierra. The Cessna 177RG had a 200-hp (150 kW) engine to offset the 300 lb (136 kg) increase in maximum weight, much of which was from the electrically-powered hydraulic gear mechanism. The additional power and cleaner lines of the Cessna 177RG resulted in a cruise speed of 146 knots (270 km/h), 22 knots (41 km/h) faster than the Cessna 177B. A total of 1,543 Cessna 177RG’s were delivered including those built in France by Reims.

Overall Model Sales

The Cessna 177 cost more than the Cessna 172. Due to the poor reputation of the early models, the Cardinal was consistently outsold by the Skyhawk despite the improvements made to the Cessna 177s built after 1971. While not a commercial failure, the Cessna 177 was not a success by Cessna’s standards. Both the Cessna 177B and Cessna 177RG ceased production in 1978, just ten years after the first Cessna 177 was introduced.

Present day

Today both the Cessna 177 and Cessna 177RG are considered desirable aircraft to own, mostly because of the large doors which offer easy entry, the aircraft’s reasonable performance for the power, active owners groups and the aircraft’s attractive looks. The Cessna 177 offers much better upwards visibility than a Cessna 172 because of its steeply raked windshield and more aft-mounted wing. The absence of an obstructing wing support strut makes the aircraft an excellent platform for aerial photography.

Aircraft Type Clubs

The Cessna 177 and Cessna 177RG family of aircraft are supported by several active aircraft type clubs, including the Cardinal Flyers Online and the Cessna Pilots Association.

Accidents and Incidents

On 11 April 1996, a Cessna 177B carrying 7-year-old Jessica Dubroff, her certified flight instructor and her father, crashed after take-off from Cheyenne Airport in Cheyenne, Wyoming, killing all on board. Dubroff was attempting to set a cross-country record for young pilots, although her instructor was thought to have been at the controls at the time of the accident. No defect in the aircraft itself was found. The accident resulted public outrage and new Federal legislation banning record attempts by non-holders of private pilot or higher certificates.

The Cessna 177 in Popular Culture

A Cessna 177 was prominently featured throughout the 1968 Russ Meyer movie "Vixen!". In the film the early-model Cessna 177 is shown flying from a mountain airstrip with four occupants and a heavy fuel load, a mission the 150-hp (110 kW) version was unable to carry out due to its lack of power. The Cessna 177’s lack of wing struts and exceptionally large doors made it relatively easy to film the actors sitting in the airplane, an important attribute in filming a low-budget, tightly-scheduled B-movie.

1977 Cessna 177 Cardinal and Cardinal II

On 30 September 1967, Cessna introduced its Model 177, a Single-engine four-seat aircraft with a cantilever wing, then powered by a 112 kW (150-hp) Lycoming engine, and intended as a luxury addition to its range of Single-engine two and four-seat models. Increased engine power was provided subsequently by installation of the 134 kW (180-hp) Lycoming O-360 engine as standard. Five versions of this aircraft became available by late 1970, of which the Model 177 was the basic standard version; this was discontinued in 1976, leaving the following four commercial versions:

- Cardinal: — Basic model, the 1977 version introducing as standard the improvements detailed for the Model 150.

- Cardinal II: — As Cardinal, plus dual controls, true Airspeed indicator, Cessna Series 300 nav/com with 360-channel com and 160-channel nav with VOR indicator, emergency locator transmitter, alternate static source, heated pitot and courtesy lights as standard.

- Cardinal RG and RG II: — Versions with retractable landing gear, described separately.

A total of 3,740 Cessna Model 177/Cardinals had been built by 1 January 1977, including Cardinal RGs, and Reims Cardinal RGs built by Reims Aviation in France.

1977 Cessna Cardinal and Cardinal II Specifications and Performance Data

- Four-seat cabin monoplane.

- Cantilever high-wing monoplane.

- Wing section modified NACA 2400 series.

- Dihedral 1° 30’.

- Incidence 3° 30’ at root, 0° 30’ at tip.

- All-metal structure except for conical-camber glass fiber wingtips.

- Modified Frise all-metal ailerons.

- Electrically-operated wide-span all-metal slotted flaps.

- All-metal semi-monocoque structure of low profile.

- Cantilever all-metal structure.

- Sweepback on fin 35° at quarter-chord.

- All-moving tailplane, with large controllable trim tab.

- Controllable rudder trim tab.

Landing Gear

- Non-retractable tricycle type.

- Improved Cessna Land-O-Matic cantilever main legs, each comprising a one-piece machined conically-tapered steel tube.

- Nosewheel is carried on a short-stroke oleo-pneumatic shock-strut, with hydraulic damper, and is steerable with rudder up to 12° each side and controllable up to 45&geg; on each side.

- Cessna main wheels size 6.00-6 and nosewheel size 5.00-5, with nylon cord tube-type tires.

- Tire pressure 2.07 bars (30 psi).

- Single-caliper hydraulic disc brakes.

- Parking brake locks both main wheels.

- Wheel fairings optional.

Power Plant

- One 134 kW (180-hp) Lycoming O-360-A1F6 flat-four engine, driving a two-blade constant-speed metal propeller.

- Pointed aluminum spinner.

- Fuel is carried in a 94.5 L (25 US gallon) integral fuel tank in each wing, vented at the wingtip.

- Total usable fuel 185 L (49 US gallons).

- Optional fuel system of 230 L (61 US gallons) capacity, of which 227 L (60 US gallons) are usable.

- Refueling point on top of each wing.

- Oil capacity 7.5 L (2 US gallons).

Accommodation

- Cabin seats four in two pairs.

- Optional seat for two children aft of rear seats.

- Baggage compartment in rear fuselage, capacity 54 kg (120 lb), with large forward-hinged external access door in portside of fuselage.

- Forward-hinged door on each side of cabin, forward of main landing gear.

- Combined heating and ventilation system.

- Glassfibre soundproofing.

- Dual controls standard on Cardinal II.

- Electrical supply from 12V 60A alternator, 12V 25Ah battery.

- 12V 33Ah battery optional.

Electronics and Equipment

- Standard electronics for Cardinal II, optional on Cardinal, include Cessna Series 300 nav/com with 360-channel com and 160-channel nav, with VOR indicator.

- Optional electronics include Cessna Series 300 360-channel transceiver, 360-channel nav/com with remote VOR/LOC indicator or VOR/ILS indicator, ADF, marker beacon with three lights and aural signal, transponder with 4096 code capability, DME, 10-channel HF transceiver, Nav-0Matic autopilot with heading control plus VOR, Series 400 glideslope receiver, and boom microphone with control wheel switch.

- Standard equipment includes stall warning indicator, control locks, windscreen defroster, omni-flash beacon, navigation lights and full-flow oil filter.

- Optional equipment (standard on Cardinal II) includes true Airspeed indicator, courtesy lights, emergency locator transmitter, alternate static source, navigation light detectors, and heated pitot.

- Other optional equipment includes control wheel map light, sensitive altimeter, directional gyro with movable heading index, carburetor air temperature gauge, economy mixture indicator, turn and bank indicator, wing leveler system, flight hour recorder, electric clock, outside air temperature gauge, rate of climb indicator, turn coordinator, sun visors, horizon and directional gyros with vacuum system, rearview mirror, individual articulating and vertically adjustable front seats, cabin fire extinguisher, headrests, child’s seat, individual reclining rear seats, safety belts and ventilation system for rear seats, stretcher, internal corrosion proofing, tinted windows, cowl-mounted landing lights, wingtip strobe lights, tail cone lift handles, tow bar, external power socket, engine primer system, quick-drain oil valve, and engine winterization kit.

Dimensions, external

- Wing span: 10.82 m (35 ft 6 in)

- Wing chord at root: 1.68 m (5 ft 6 in)

- Wing chord at tip: 1.22 m (4 ft 0 in)

- Wing aspect ratio: 7.31

- Length overall: 8.31 m (27 ft 3 in)

- Height overall: 2.62 m (8 ft 7 in)

- Tailplane span: 3.61 m (11 ft 10 in)

- Wheel track: 2.53 m (8 ft 3½ in)

- Wheelbase: 1.94 m (6 ft 4½ in)

- Propeller diameter: 1.93 m (6 ft 4 in)

- Passenger doors (each):

- Height: 1.12 m (3 ft 8 in)

- Width: 1.22 m (4 ft 0 in)

- Height to sill: 0.69 m (2 ft 3 in)

Dimensions, Cabin, internal

- Length: 4.46 m (14 ft 7½ in)

- Max width: 1.22 m (4 ft 0 in)

- Max height: 1.13 in (3 ft 81/2 in)

- Wings, gross: 16.2 m² (174.0 ft²)

- Ailerons (total): 1.75 m² (18.86 ft²)

- Trailing-edge flaps (total): 2.74 m² (29.50 ft²)

- Fin: 1.02 m² (11.02 ft²)

- Rudder: 0.60 m² (6.41 ft²)

- Tailplane, including tab: 3.25 m² (35.01 ft²)

Weights and Loadings

- Weight empty: Cardinal — 695 kg (1,533 lb); Cardinal II — 707 kg (1,560 lb)

- Max T-O weight: Cardinal and Cardinal Il — 1,134 kg (2,500 lb)

- Max wing loading: Cardinal and Cardinal II — 70.3 kg/m² (14.4 psf)

- Max power loading: Cardinal and Cardinal II — 8.46 kg/kW (13.9 lb/hp)

Performance (Cardinal and Cardinal II at max T-O weight)

- Max level speed at S/L: 139 knots (257 km/h; 160 mph)

- Max cruising speed, 75% power at 3,050 in (10,000 ft): 130 knots (241 km/h; 150 mph)

- Stalling speed, flaps up 55 knots (102 km/h; 63 mph) CAS Stalling speed, flaps down: 46 knots (85 km/h; 53 mph) CAS

- Max rate of climb at S/L: 256 m/min (840 ft/min)

- Service ceiling: 4,450 m (14,600 ft)

- T-O run: 229 m (750 ft)

- T-O to 15 m (50 ft): 427 m (1,400 ft)

- Landing from 15 m (50 ft): 372 m (1,220 ft)

- Landing run: 183 m (600 ft)

- Range, recommended lean mixture with allowances for start, taxi, T-O, climb and 45 min reserves at 45% power:

- Max cruising speed at 3,050 in (10,000 ft) with standard fuel: 535 nm (991 km; 616 miles)

- Max cruising speed at 3,050 m (10,000 ft) with max fuel: 675 nm (1,250 km; 777 miles)

- Econ cruising speed at 3,050 in (10,000 ft) with standard fuel: 615 nm (1,139 km; 708 miles)

- Econ cruising speed at 3,050 in (10,000 ft) with max fuel: 780 nm (1,445 km; 898 miles)

Cessna 177B Specifications and Performance Data

General Characteristics

- Crew: 1 pilot

- Capacity: 3 passengers

- Length: 27 ft 8 in (8.44 m)

- Wingspan:

- Height: 8 ft 7 in (2.62 m)

- Wing area: 174 ft² (16.2 m²)

- Empty weight: 1,495 lb (680 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 2,500 lb (1,100 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Lycoming O-360-A1F6D flat-4 engine, 180-hp (135 kW)

Performance Data

- Maximum speed: 136 knots (157 mph, 250 km/h)

- Cruise speed: 124 knots (143 mph, 230 km/h)

- Range: 604 nm (695 mi, 1,120 km)

- Service ceiling: 14,600 ft (4,450 m)

- Rate of climb: 840 ft/min (4.27 m/s)

Cessna Cardinal RG and RG II

On 3 December 1970 Cessna announced a further version of its Cardinal Single-engine four-seat cabin monoplane, with hydraulically-retractable tricycle-type landing gear, a more powerful fuel-injection engine and a number of different standard and optional items.

The landing gear is retracted by a simplified self-contained hydraulic system, with an electrically-powered hydraulic pump that provides a maximum system pressure of 103.5 bars (1,500 psi). The hand pump, for emergency retraction or extension of the gear, is designed to eliminate the need for complex sequencing valves in the hydraulic power pack. When the landing gear is retracted the nose unit is faired by wheel doors; the main gear is retained flush with the fuselage and has no wheel doors. Two versions of the Cardinal RG were available for 1977:

Cardinal RG: — Standard retractable-gear version, introducing the same standard and optional improvements as the fixed-gear Cardinal, plus new standard features which include a new rectangular hour meter, and a standardized fuel selector.

Cardinal RG II: — Specially-equipped version of the Cardinal RG which includes as standard Cessna Series 300 nav/com with 720-channel com and 200-channel nav with remote VOR/LOC indicator, ADF, transponder, 200A Nav-O-Matic autopilot with VOR/LOC track and intercept functions, horizon and directional gyros, true Airspeed indicator, dual controls, navigation light detectors, external power socket, heated pitot, courtesy lights and emergency locator transmitter. Nav-Pac IFR option adds a second 300 nav/com with VOR/ILS, 400 glideslope and 400 marker beacon. By 1 January 1977, a total of 1,182 Cardinal RGs had been delivered, the total including 153 produced by Reims Aviation in France.

- Wing section NACA 64A215 at root, NACA 64A412 at tip.

- Incidence 4° 7’ at root, 0° 43’ at tip.

- All-metal structure except for glassfibre wingtips.

- All metal ailerons.

- Electrically-operated all-metal trailing-edge flaps.

- Cantilever all-metal structure with swept vertical surfaces.

- All-moving tailplane with large controllable trim tab.

- Hydraulically-retractable tricycle type.

- Tubular spring steel main gear struts, retracting rearward into fuselage.

- Nosewheel, which retracts rearward, is carried on a short-stroke oleo-pneumatic shock-strut with hydraulic damper, and is steerable.

- Nosewheel enclosed by doors when retracted.

- Hydraulic brakes.

- Parking brake.

- One 149 kW (200-hp) Lycoming IO-360-A1B6D) flat-four engine, driving a two-blade constant speed metal propeller.

- Pointed metal spinner.

- One 115 L (30.5 US gallon) integral fuel tank in each wing.

- Total fuel capacity 230 L (61 US gallons), of which 227 L (60 US gallons) are usable.

- Refueling point in top of each wing.

- Oil capacity: 7.5 L (2 US gallons).

- Cabin heated and ventilated.

- Baggage compartment in rear fuselage, capacity 54 kg (120 lb), with large forward-hinged external access door on portside of fuselage.

- Electrical system powered by a 14V 60A alternator and 12V battery for operation of wing flaps, hydraulic motor, electronics and lighting.

- Hydraulic system for landing gear retraction and brakes.

- Optional items are as detailed for the Cardinal, plus Cessna Series 400 720-channel transceiver, 720-channel nav/com with remote VOR/LOC indicator or VOR/ILS indicator, ADF with digital tuning, transponder with 4096 code capability, and a blind altitude encoder.

- Standard equipment includes inertia safety belts for pilot and co-pilot and omni-flash beacon at tip of fin.

- Wheel track: 2.39 m (7 ft 10 in)

- Propeller diameter: 1.98 m (6 ft 6 in)

- Weight empty: RG &mdash: 772 kg (1,703 lb); RG II — 801 kg (1,765 lb)

- Max T-O weight: 1,270 kg (2,800 lb)

- Max wing loading: 78.6 kg/m² (16.1 psf)

- Max power loading: 8.52 kg/kW (14.0 lb/hp)

Performance (at max T-0 weight)

- Max level speed at S/L: 156 knots (290 km/h; 180 mph)

- Max cruising speed (75% power) at 2,135 m (7,000 ft): 148 knots (273 km/h; 170 mph)

- Econ cruising speed at 3,050 m (10,000 ft): 121 knots (223 km/h; 139 mph)

- Stalling speed, flaps up: 57 knots (106 km/h; 66 mph) CAS

- Stalling speed, flaps down: 50 knots (92 km/h; 57 mph) CAS

- Max rate of climb at S/L: 282 m/min (925 ft/min)

- Service ceiling: 5,210 m (17,100 ft)

- T-O run: 271 m (890 ft)

- T-O to 15 m (50 ft): 483 m (1,585 ft)

- Landing from 15 m (50 ft): 411 m (1,350 ft)

- Landing run: 223 m (730 ft)

- Max cruising speed at 2,135 m (7,000 ft) with 227 L (60 US gallons) usable fuel: 715 nm (1,324 km; 823 miles)

- Econ cruising speed at 3,050 m (10,000 ft) with 227 L (60 US gallons) usable fuel: 895 nm (1,657 km; 1,030 miles)

- Photos, John Shupek, Copyright © 2009 Skytamer Images (Skytamer.com). All Rights Reserved

- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. "Cessna 177." [Online] Available https://en.Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.org/wiki/Cessna_177, 15 September 2009

- Taylor, John W. R. (ed.) Jane’s All The World’s Aircraft 1977-78. London, Jane’s Yearbooks, 1977, ISBN 0 531 03278-7, pp 267-268.

- AVwebFlash Current Issue

- AVwebFlash Archives

- Aviation Consumer

- Aviation Safety

- IFR Refresher

- Business & Military

- eVTOLs/Urban Mobility

- Experimentals

- Spaceflight

- Unmanned Vehicles

- Who’s Who

- Video of the Week

- Adventure Flying

- AVWeb Classics

- CEO of the Cockpit

- Eye of Experience

- From The CFI

- Leading Edge

- Pelican’s Perch

- The Pilot’s Lounge

- Brainteasers

- Company Profile

- Flying Media Offers

- Question of the Week

- Reader Mail

- Short Final

- This Month In Aviation Consumer Magazine

- This Month In IFR Magazine

- Farnborough

- HAI Heli Expo

- Social Flight

- Sun ‘N Fun

- Women in Aviation

- Accidents/NTSB

- Aeromedical

- FAA and Regs

- Flight Planning

- Flight Schools

- Flight Tracking

- Flight Training

- Flight Universities

- Instrument Flight

- Learn to Fly

- Probable Cause

- Proficiency

- Risk Management

- Accessories and Consummables

- Aircraft Upgrades

- Equipment Reviews

- Maintenance

- Refurb of the Month

- The Savvy Aviator

- Tires/Brakes

- Used Aircraft Guide Digest

- Electronic Flight Bag

- Engine Monitors

- Portable Nav/Comm

- Specifications

- Register Now

- Customer Service

- Reset Password

- Sign up for AVweb Flash

- Read AVweb Flash

- Aviation Publications

- Contact AVweb

Joby Completes Pre-Production Flight Testing, Eyes Air Certification For Electric Air…

LSA-Based Exploding Drones Used In Attacks On Russia

Archer Reports Success With Battery-Pack Drop Testing

Beta Technologies Alia CTOL Impresses At Cape Cod Debut

NATA’s Hard Line Complicates Fuel Quest

CEO Of The Cockpit: Master Of My Domain

Sun ‘n Fun 2024: Innovation And Grit

From The Inside, Things Look Even Worse For Air Traffic Control

Going Boeing

Picture Of The Week: May 3, 2024

Featured Video: RC Concorde

Picture Of The Week: April 26, 2024

Featured Video: Airthre’s Cabin Oxygen Generator

Short Final: Better-Than-Passing Grade

Short Final: Student Workout

Short Final: Mirage Alert

New T-Shirt Line Launched By Aeroswag

Alaskan Instructor Wins Martha King Scholarship

Sun ‘n Fun 2024: Bose A30 Headset

Sun ‘n Fun 2024: Garmin VHF Radios

Sun ‘n Fun 2024: Dynon Unveils 12-Inch Display

FAA Issues Warning On Potential Wing Cracks In Revo Inc. Amphibious…

Beefier Batteries Add Electric Airplane Utility

Bipartisan Congressional Approval For Long-Term FAA Reauthorization

C-54 Fuel Transport Down In Alaska (Updated With Video Link)

‘Climate-Smart’ Corn-Based SAF Rules Defined

G100UL Maker Refutes NATA Claim That It’s Not Ready To Sell

NATA Challenges GAMI’s Assertion Of ‘Commercial Availability’ of G100UL

EAGLE Projects Approval For PAFI Unleaded Fuel In 2025 (Corrected)

ForeFlight Introduces Reported Turbulence Map

uAvionix Gets FAA Airport Surface Situational Awareness Contract

Sun ‘n Fun 2024: Garmin’s GTN 750Xi Radar Interface

- features_old

Cessna 177 Cardinal

An economical cruiser that looks more modern than a skyhawk, the fixed-gear cessna 177 cardinal is a good choice for performance-seekers on a budget..

Although the design is more than four decades old, the Cessna 177 Cardinal—with its racy sloped windshield, wide doors and strutless wings—looks more modern than the newest Skyhawks coming out of Cessna’s Independence, Kansas, plant. Yet, sadly, the Cardinal is a poster child for why innovation and audacity in general aviation development has often met dismal results in the market. Despite high expectations for a design that would usher in new thinking in light aircraft, the Cardinal had a rocky start and was gone from Cessna’s inventory a decade after it emerged.

Although Cessna’s 177 Cardinal was intended to be a Skyhawk killer, the venerable 172 outlasted it and continues to be a mainstay in Cessna’s current piston aircraft line. Still, the Cardinal enjoys enthusiastic support among owners for many of the reasons that Cessna thought it would become a hit. And despite its warts and shortfalls, many of which have been rectified, the Cessna Cardinal is an excellent choice for owners who want a bit more performance than the Skyhawk offers without stepping up to the 182 Skylane.

Cessna 177 Cardinal Model History

By the time the Cessna 177 Cardinal appeared, the Cessna 172 was long in the tooth, having been on the market for 12 years. It was time for something new. When the first Cardinals hit dealers in 1967, buyers were clearly confronted with just that.

Besides being sleeker and strutless, the new model had a stabilator, just like Piper’s competing Cherokees did. With the wings placed aft of the main part of the cabin, the pilot sat ahead of the leading edge, which produced better inflight visibility than any of the previous Cessnas had.

The 1968 Cardinal had a fixed-pitch prop and a Lycoming O-320-E2D. The airplane was designed with the 180-HP engine in mind, but Cessna had ordered 2000 150-HP engines from Lycoming—its first purchase from the company.

Cessna was so confident that the Cardinal would succeed that the Skyhawk production line was actually shut down in anticipation of the Hawk’s planned demise. Things didn’t work out that way, however.

The 150-HP, fixed-pitch prop Cardinal looked great, but gained a reputation for lethargic climb performance. In reality, it took some time for Cessna to figure out that pilots were loading and flying the Cardinal as if it were a 172—which meant they were often over gross weight—since it carried 10 more gallons of fuel and had a heavier empty weight. Worse, Cessna discovered that pilots were climbing the aircraft well below Vy (Vy in the 172 was 10 MPH slower than it was for the Cardinal). When flown and maintained properly, the 150-HP Cardinal actually outclimbed and outran the 150-HP 172.

Cessna produced 1164 Cardinals that first year, but word got around about the airplane’s performance. The following year, sales slumped, while other models were selling well. In fact, no more than 250 Cardinals were built in any single year after the airplane’s introduction. (A total of 2752 were built, eventually.)

The Cessna Cardinal’s wing was a high-performance NACA 6400 series airfoil, the same one used in the Aerostar and Learjet. But that airfoil tends to build up drag quickly at high angles of attack and low speeds, which isn’t a good trait for an airplane flown by low-time, step-up pilots. The stall speed was higher than the Skyhawk’s, too.

In the late 1970s, an accident involving an original model 150-HP Cardinal prompted a series of test flights (performed by an expert test pilot working for plaintiffs’ attorneys) in an attempt to prove that the 177 Cardinal didn’t live up to its performance figures. The accident in question involved a pilot who supposedly had operated the airplane as described in the manual and wound up clipping the trees at the end of the runway. But because these trials weren’t conducted by the FAA or Cessna, no official action was taken against Cessna. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that the expert test pilot was proven wrong in court about his claims of the Cardinal’s short field takeoff performance.

Touchy Controls for the Cessna 177 Cardinal?

The 1968 Cardinal as originally delivered was quite sensitive on the controls, particularly in the pitch mode. In crosswinds, the stabilator could stall in the landing flare, resulting in a sudden loss of tail power and an unexpected plunge of the nosewheel onto the runway.

Porpoising and bounced landings were commonplace. Various studies showed a disproportionately high rate of hard landings and takeoff stall-mush accidents for the early models.

Cessna realized it had made a major gaffe with the Cardinal. It restarted the Skyhawk production line (using the 150-HP engines that had been purchased for the Cardinal) and set to work fixing the Cardinal’s problems. Under the “Cardinal Rule” program, it retrofitted leading edge slots to stabilators on all Cardinals already in the field and made them standard in new production machines. This fixed the stabilator-stalling problem, although pitch forces remained lighter than average for a Cessna.

The 1969 model (177A) had a 180-HP Lycoming engine, plus there was a 150-pound increase in gross weight to compensate for both the engine’s increased mass and some shortcomings in the original airplane’s useful load. The stabilator-to-wheel control linkage ratio was changed to slow the response in pitch slightly. The nosegear/firewall area was also beefed up to prevent bent metal from bounced landings. This fix was offered as a retrofit to 1968 models via an early bulletin.

Despite the improvements, 1969 sales nose-dived to about 200 units, while Skyhawk sales rebounded to their former league-leading levels. In 1970, Cessna made more major improvements, yielding the 177B Cardinal. The 6400 series airfoil was changed to a more conventional 2400-series similar to the Skyhawk’s, plus a constant-speed propeller was added for better takeoff and climb performance.

At last, the Cardinal had all the makings of a good airplane. From 1971 on, the Cessna Cardinal got only minor changes. In 1973, a 61-gallon fuel capacity became optional, and cowling improvements boosted cruise speed from 139 to 143 MPH. In 1978, a 28-volt electrical system was added. These days, that’s appreciated for avionics upgrades.

In 1975, speed went up again, but this was really mostly the result of some creative number crunching by Cessna. For example, the cruise RPM limit was increased so that 75 percent power could be obtained at 10,000 feet instead of at 8000 feet, as before.

At the time, Cessna’s marketing department called the Cardinal “the fastest 180-HP, fixed-gear airplane in the world.” Not true—the Grumman Tiger was at least 8 or 9 knots faster—at about the same price.

Finally, 1976 brought a new instrument panel. The older panels had a 1960s Buick-style split panel arrangement that did little but rob panel space. The 1976 panel is a more conventional, full-width design.

Throughout this period, the airplane continued to be a slow seller, despite Cessna’s successful efforts to fix the original Cardinal’s quirks. It was the only Cessna single that didn’t lead its category in sales. Piper’s Cherokee 180/Archer beat it handily, as did the upstart Grumman Tiger.

In 1977, Cessna finally gave up on further changes to the 177 Cardinal. The Hawk XP was introduced—same performance, less attractive, worse handling, noisier, more cramped, much higher fuel consumption and engine maintenance, lower engine reliability and TBO. Such is the way of GA marketing, however.

Meanwhile, Cessna added ARC radios to the standard equipment list and boosted the Cardinal’s price by about 50 percent. Customers preferred the Hawk XP by a four-to-one margin. Price and competition from Grumman and Piper undoubtedly had a lot to do with the poor sales, but the Cardinal’s first year reputation clung to the model like a cheap suit.

In 1978, Cessna made one last-ditch effort to save the Cardinal. The company spruced it up with some fancy interior appointments and radio packages—along with an absurdly high price tag—and called it the Cardinal Classic. Only 79 intrepid souls sprang for the gussied-up airplane.

No surprise here because the average flyaway price of a Cardinal Classic was more than $50,000, compared to $30,000 for a Tiger or under $40,000 for an Archer. But the Classic remained devalued for quite some time. Normally, an airplane depreciates from its new value for eight years before resuming an upward value climb, eventually surpassing its new price.

As of spring 2014, a Cardinal Classic retails for around $45,000, although some may fetch more, depending on avionics and other mods. We saw one at AirVenture last summer decked out with a Garmin G500 glass display, dual GTN750 navigators, a high-end autopilot, plus leather interior and other luxuries. Its owner was asking nearly $70,000. Still, the airplane eventually took about 20 years to regain close to its original value, which is a dismal price performance compared to other models in this or any other class.

But there’s a silver lining in that cloud for potential buyers. Because other models have had price spikes—namely the Archer and the Tiger—we think the Cessna Cardinal represents a better value, based on pure performance alone. With price parity, the buyer can choose the greater comfort of the Cardinal or the speed of the Tiger without paying a sizable premium either way.

Cessna 177 Cardinal Performance

The Cessna Cardinal’s performance is adequate by 1970s standards for 180-HP airplanes but more modern designs best it. Book cruise speeds range from 120 to 130 knots, while the 150-HP 177 is listed at 115 knots. Those numbers fall short of the Grumman Tiger (139 knots) and are about on par with the Cherokee 180/Archer and better than the pokey Beech Sundowner. New-age designs such as the Diamond Star and Cirrus SR20—still four-place, fixed-gear cruisers like the Cardinal—obviously do better.

Owners report real-world performance reasonably close to book figures, except for the 1968 model. Typical figures: 125 knots on 9 to 10 GPH. The 1968 model, judging from some owner reports, is lucky to cruise at 110 knots, although we suspect faulty rigging has a lot to do with these low numbers. Climb rate is about average for this class of aircraft—again, with the exception of the 1968 airplane, whose owners universally complain about its lethargic climb performance.

Owners typically report useful loads in the 850-950-pound range, depending on installed equipment. That’s a bit less than the Cherokee 180 or the Grumman Tiger, but perhaps not enough to rule in favor of one or the other solely on payload issues.

Assuming a fairly typical 900-pound useful load and 49-gallon tanks, the Cessna Cardinal has roughly 600 pounds for people and bags once the tanks are filled. That’s three FAA-standard people—well, a little less if “standard” becomes 195 pounds—and 90 pounds of luggage.

If you want to carry four full-size people and 100 pounds of luggage, you’ll be limited to perhaps 20 gallons of fuel—barely enough to fly anywhere safely. Weight limitations make the Cardinal essentially a three-passenger airplane, or at best a two-plus-two with adults and kids aboard, certainly not four large rear-ended adults—chose pax wisely.

With full tanks, the Cessna 177 Cardinal has decent but not exceptional range. The 49 gallons usable and typical 9- to 10-GPH fuel flow allow the Cardinal to fly four hours with reserves and cover more than 500 miles. The 60-gallon tanks available on post-1973 models boost endurance by an hour and range by 150 miles, at the expense of 66 pounds of payload.

A typical 60-gallon Cardinal with tanks full can carry just 540 pounds of cabin load. The 1968 150-HP Cardinal (2350 pounds gross) has a gross weight 150 pounds lower than the 177A and 177B. Empty weight is only a bit less, so the 177’s equipped useful load may be as low as 750 pounds. Put in four 170-pounders and 70 pounds of luggage and there’s zero—yes zero—left for fuel.

Legally speaking, the 177s converted to the 180-HP constant-speed setup are worse, since useful load can’t be legally increased while the new engine/prop package is about 50 pounds heavier. But most pilots of the 180-HP 177s fly as if they have 177As or Bs. From the performance point of view, they’re perfectly safe doing that. As far as the landing gear and wing spar go, we’re not so sure. Interestingly, the c.g. is so long that if you abide by the 120-pound baggage restrictions, it’s nearly impossible to load out of c.g., even with two heavy-weights up front (but no passengers in the back), or two heavyweights in the back and a lightweight pilot up front.

Cessna 177 Cardinal Cabin, Ergonomics

One goal Cessna hoped to achieve with the Cardinal was to improve cabin comfort and design over the 172/182 series aircraft and to best the competition. In this regard, it succeeded. The Cardinal cabin is fully 6 inches wider than a Cherokee’s and puts its sibling Skyhawk to shame.

The Cardinal baggage compartment is enormous and relatively easy to get to through a dedicated door. As noted, the airplane’s wing sits higher and farther back, allowing excellent visibility out of the panoramic windshield. Unlike the other high-wing Cessnas, the pilot’s vision up and to the side is not blocked by the wing.

To a degree, this gives the pilot some of the best of both worlds—good visibility up, down and to the side.

The Cessna Cardinal’s enormous doors offer another benefit: Of all airplane models we’re familiar with, it’s the easiest to get in and out of. There’s no wing strut to get in the way and the floor sits lower to the ground than other high-wing Cessnas, so the step up is a small one.

Those doors require special care, by the way. Owners tell us that a gust of wind can damage the door and surrounding sheet metal when it opens violently. One reader pointed out that with both doors open and the airplane pointed downwind, the doors can act as fairly efficient sails.

Overall, the Cardinal is probably the roomiest four-place airplane made, not counting semi-six-seaters like the Bonanza or Cessna 210. The tradeoff for a big cabin, of course, is speed. The main reason for the Tiger’s speed advantage over the Cardinal is that the latter has a bigger passenger compartment while the former is tight, with a minimal backseat and smaller frontal area.

Cessna 177 Cardinal Handling/Fuel Control

The Cardinal wins praise from owners for its handling qualities. Despite having lighter control forces than other Cessnas, the airplane makes a fine instrument platform. What was once considered an airplane that was “twitchy” in pitch is now considered more normal in that other airplanes with even lighter controls were subsequently marketed, such as the Grumman-American Cheetah and Tiger.

Nevertheless, pitch control forces are light and effective, even at low speed (particularly compared to the notoriously ponderous Skyhawk and Skylane), and Skyhawk pilots are sometimes surprised by the responsiveness and pitch authority. On takeoff, the Cessna Cardinal must be rotated with firm wheel pressure, at least with only two people in front and flaps up. This is, in part, because the pilot sits well ahead of the wing; all that weight out front has its consequences. Dropping 10 to 15 degrees of flaps for takeoff, however, will require a much less vigorous rotation moment.

In cruise flight, the Cessna 177 Cardinal is a steady IFR airplane—if you can get it trimmed out laterally and keep the fuel balanced. Several owners reported gross fuel-flow discrepancies when the fuel selector is on “both,” with the tendency for fuel to flow from the left wing. Left-right switching every half hour may be necessary to maintain good lateral trim or a few seconds of uncoordinated flight to clear the liquid from tank vent system, which is what causes the imbalance.

Otherwise, the Cessna Cardinal’s fuel system is well designed. There’s a reservoir under the floor, which means that there’s essentially no chance of unporting as the result of maneuvering with low fuel. There is, however, a warning in the handbook about long nose-down descents with low fuel, which tends to run to the front of the wing tanks. The tank vents are cross-connected to the opposite wing and are led through the trailing edge where ice buildup shouldn’t be much of a concern.

Cessna 177 Cardinal Maintenance

At least some owners are attracted to the Cardinal because it has a benign maintenance history with few expensive gotchas.

Owners tell us annual inspections typically cost about $1000 to $1500 for the basic once-over, which is typical for this class of airplane when performed by higher-end shops and thorough mechanics. But this can vary widely. You might have to spend $5000-plus to bring back a barn dweller to airworthy status. Parts aren’t a real problem, despite the model’s relatively low population.

One other major maintenance factor: ARC radios, which are finally starting to disappear. Most Cessna Cardinals came with avionics manufactured by Cessna’s onetime captive ARC company. Starting in the mid-1970s, the quality of ARC radios began to decline. ARC equipment rated dead last in our avionics owner surveys during that period and there were big shake-ups at the ARC factory at the time. Many owners have replaced part or all of older ARC panels. The 28-volt digital ARC navcomm radios, for example, are more serviceable than the mechanical 14-volt versions. We caution against spending money on these.

There are few onerous ADs on the Cardinal. A couple of shotgun ADs (2000-06-01 and 99-27-02) deal with fuel valves and strainers; not a big deal. Another shotgun AD is a big deal, however. It’s 98-2-8, which calls for inspection of the crank bore for corrosion on the fixed-pitch airplanes. At the least, it’s repetitive, and it could mean replacement of the crank. Make sure it has been done.

Cessna 177 Cardinal Mods and Owner Groups

The big mod for the Cessna Cardinal is the one that converts the 150-HP model to the 180-HP constant-speed Lycoming. The conversion is quick and easy, basically a bolt-on job, so no surprise that hundreds have been done.

Two STCs are available, one from Avcon Conversions (316-284-2842) and one from Bush (800-752-0748). The two are similar. Both sell STC paperwork and kit parts; you buy an engine and prop elsewhere and hire out the shop to do the job yourself.

The 1968 177A and B are on the same type certificate and some have upgraded to the later Cessna-selected counterbalanced engine/prop configuration.

Horton Industries (800-835-205) offers a STOL kit for the Cardinal consisting of a leading-edge cuff, conical wing tips and vortex generators on the vertical fin. The above-mentioned Bush also offers a STOL mod for the Cardinal, as does Sierra Industries. Contact Sierra at 888-835-9377 or www.sijet.com.

There’s a burgeoning business in Cardinal speed mods. Canadian Roy Sobchuck came up with most of them and they’re sold by Maple Leaf Aviation (204-728-7618). The mods include a nose strut fairing—claimed speed gain of 8 MPH—tailcone fairing (177A/B only, 7 MPH claimed but seldom seen) exhaust stack fairing, for a 2 MPH gain and a 75-degree drop in engine temperature.

The company also sells landing light covers, cowl cheek fairings, fuel drain fairings, ADF loop covers and wheel pants for which minor speed increases are claimed.

Cardinal owners have a choice of two major organizations. The Cessna Pilots Association ( www.cessna.org and 805-922-2580) is the biggest overall Cessna group and publishes useful technical info, much of it of interest to other single-engine Cessna owners.

For the true Cardinal fan, we recommend the highly regarded Cardinal Flyers Online, ( www.cardinalflyers.com ) which has a first-rate website and a near daily e-mail newsletter.

Cessna 177 Cardinal Owner Feedback

I purchased my 1975 177B in 2007. Since then, I’ve flown it all over the country and twice, coast-to-coast. The two best attributes are the cabin (longer and wider than a 182) and the improved visibility in a turn compared to other Cessnas.

My Cardinal has a three-blade prop and while I love the way it looks, I wouldn’t recommend it. This is not because it results in lower cruise speeds, which I haven’t observed, but because of the significantly increased weight on the nose as well as the unnecessary drag during descent. This makes power- off landings a challenge, requiring a large and well-timed pitch change between short final and flare. Normal and crosswind landings are simple as long as a small amount of power is carried through the approach and the throttle is pulled to idle just prior to flare.

Insurance is around $800 per year and the airplane has been relatively inexpensive to maintain. I associate most of the more expensive repairs with high time and age rather than the aircraft type. A few issues unique to the Cardinal that I’ve dealt with are overheating (typically on 90-degree-plus days, solved by flushing the oil cooler and installing the Maple Leaf exhaust fairing). There are loose door hinges and nose wheel shimmy. Most issues are well-understood thanks to the exceptional support provided by Cardinal Flyers Online, run by Paul Millner and Keith Peterson, plus an array of knowledgeable owners who gather around their site.

Chris Berg,Woodbridge, Virginia

I’ve owned a 1973 Cardinal since 2010 and bought it for training before even getting my license (I was a little worried that I may have been a bit impulsive). However, more than three years later, I’ve had no regrets. When I purchased it, the plane was almost all original, including engine, paint and interior. It has always been hangared and only had 1160 totals hours since new. Since purchase, I’ve added a Garmin GNS430W, JPI 830 engine analyzer, PMA8000 intercom, Alpha Systems Angle of Attack indicator and a Guardian CO detector that I connect to cabin iPads.

I paid $51,000 for the plane and generally flight plan for a fuel burn of 11 GPH, which is conservative. For insurance, I have a $1 million smooth policy that costs under $1400 per year, which is probably a bit higher than it will be when I get my instrument rating and over the 500-hour hurdle. It’s a little hard for me to separate out the pure maintenance costs versus the upgrades I’ve made, but it would probably come in at about $2500 per year. I use Savvy Aircraft Maintenance, who coordinates with Cecil County Aero in Elkton, Maryland. Both have been outstanding. Although the 1650-hour engine is 40 years old, it seems to be doing fine and I am not yet considering an overhaul.

The cabin feels relatively roomy and my wife doesn’t get claustrophobic. It’s also a lot easier to get in and out of compared to the low wing planes we looked at before buying the Cardinal. I flight plan for 116 knots, so it’s not real fast but it cuts my trips from Wilmington, Delaware, to our summer place on Cape Cod from about eight hours driving time to around 2.5 hours in the air.

Steve Furlong,Via email

I have owned N1419C, a 1978 Cardinal Classic for six years and have flown it for just over 1000 hours. I have used it primarily to transport passengers for Angel Flight and Life Line Pilots. Most of the flights are to transport passengers for cancer treatment but also to transport children to summer special needs summer camps in northern Minnesota. I have also had a flight for Pilots and Paws, transporting rescue dogs, which I found to be a very rewarding experience.

Many of these passengers find it difficult to get in and out of small airplanes, but the Cardinal’s wide doors and low stance make it much easier for the physically limited passengers to get in and out of the plane. These wide doors can be a problem if they get caught in a tail wind because they are so big, but this problem is solved by installing the Door Steward modification. The Cardinal Flyers Online web page has been an invaluable aid in learning about the plane, the many upgrades and modifications, plus special maintenance solutions. It has been a very reliable and comfortable plane—especially for the needy passengers I transport.

Derek Sharvelle,Battle Ground, Indiana

Our family of four has owned a 1968 Cardinal for five years. The Cardinal has proven to be a versatile airplane and flying in it is a real treat compared to other Cessnas. Probably the most obvious to pilot and passengers is the absence of a wing strut. This results in improved views down, but most noticeable is the much easier entrance and egress. The large size of the doors also contributes to easy access, but they do require caution when opening in a tail wind.

Another feature of the Cardinal is the location of the front of the wing—it’s farther back than other Cessna models and results in improved visibility for the pilot and front passenger when looking up.

Our Cardinal has the original Lycoming O-320-E2D with the LyCon 160-HP STC. The performance is such that I am routinely comfortable taking off from our home airport that is 5000 feet above sea level. Not all pilots would be comfortable with the climb rate in the summer, which is often 200-300 FPM at our elevation.

We live in the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains, which means that 14,000-foot peaks are only about 30 miles west. As a result, I avoid going directly west through the mountains but have experienced no difficulties. Our Cardinal burns a little over 8 GPH and I flight plan for 110 knots, making it a fairly economical flyer. We have to decide whether the Cardinal is full of fuel or people, but with minimal planning, it routinely suits our missions.

Having done owner-assisted annuals on the Cardinal, I have not found it a difficult plane to work on. More important though is that my mechanics have not found it difficult to work on. However, they do remind me on occasion that there are many parts on the Cardinal that are unique, since it was a clean slate design.

My annuals typically run around $1500, with the high being $2600—comparable with other four-cylinder, fixed-gear, fixed-pitch aircraft. The insurance on the Cardinal is also very reasonable, and I have managed to get decent coverage for under $600 a year.

One of the benefits of being a Cardinal owner is the enthusiastic following of the aircraft. From model-specific support groups like Cardinal Flyers Online, to the many modifications from Roy Sobchuk, it is relatively easy to get expert support and improvements to keep a Cardinal safe and efficient.

Owning a Cardinal is just enough different to be fun. Not everyone has seen one and most would agree that it was one of Cessna’s best efforts when it comes to ramp appeal. The 150-160-HP Cardinals are not as fast as they look, but as all pilots know, looks count for something.

Tom Lynch,Fort Collins, Colorado

We note, with sadness, that the designer of the Cardinal, Ted Moody, died this past February after a protracted battle with cancer.

Rick Durden, our senior editor, spent extended periods of time with Mr. Moody from 1979 through 1994 and had access to the original design records of the Cardinal. He recalls Mr. Moody’s description of the intense secrecy surrounding the development of the airplane, including referring to it as the “Model 172J” so that competitors would think that Cessna was just coming up with another model year change for the 172. In fact, the original Cardinal had no virtually no parts in common with the 1967 172 beyond such things as brakes, wheels and tires. The Cardinal was the nearest to a clean sheet of paper design any of the manufacturers had created in some years.

Durden recalls Mr. Moody’s description of how devastated he was upon learning of the first fatal Cardinal accident because, as Durden put it, “Ted Moody put his heart and soul into that airplane.”

This article originally appeared in the April 2014 issue of Aviation Consumer magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Aviation Consumer !

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Log in or Register to leave a comment

AVweb Insider

Featured video.

- Privacy Policy

Cessna Cardinal 177 AB Series Data, History, & More

Cessna By Textron Aviation

Before creating his own initial aircraft, Cessna’s founder Clyde V. Cessna made his first appearance at an airshow in 1911. It was there that he quickly became interested in designing and producing aircraft. With experience as a mechanic and auto salesman, Clyde put together his aircraft with a kit from Queens Airplane Company in the Bronx. Over time, Clyde became a fairly good pilot.

In 1916, Clyde got the opportunity to use a space for his aircraft dreams rent-free on one condition – any new aircraft he made had to have the name of a particular car model called “Jones-Six” painted on the underside of its wings.

In 1917, he built the Comet. However, World War I impacted his vision, halting sales and production altogether as most critical parts and supplies became essential for war use. After coming to terms with his failed venture, he returned to farming.

Years later, in 1925, wealthy businessmen Walter Beech and Lloyd Stearman offered Cessna an opportunity to build and produce more aircraft. After teaming up, they created Travel Air Manufacturing Company with Cessna as its president. But Cessna didn’t enjoy his role as president and missed being heavily involved with aircraft design and production. So two years later, Cessna teamed up with Victor Roos to create the Cessna-Roos Company. His partner Roos left the business shortly after for another job.

Cessna had successful sales through the business’s A and D series, but tough times were still ahead. After private aircraft sales fell to an all-time low in 1931, Cessna closed his company again.

By 1933, Cessna’s nephew Dwane Wallace obtained his degree in Aeronautical Engineering from Wichita University. He eventually worked for Beech Aircraft Company, where he convinced executives to allow his uncle to reopen his shop and continue making aircraft. At the time, Beech occupied a small section of Cessna’s former factory.

After Cessna’s retirement in 1936, he allowed the sale of all of his shares to his nephews, Dwane and Dwight Wallace. Under the Wallace Brothers’ leadership, Cessna designed and built its first twin-engine aircraft in 1938. Before World War II started, government demands from the U.S. and Canada poured in for aircraft to be used for military training. From there, Cessna’s business expanded quickly, embracing its newfound success.

Creating The Cardinal

Driven by a need to create a higher-performing 172, Cessna’s engineers began working on the 177 in the 1960s, later producing the first 177. While it had a sleek new look, aviation enthusiasts and pilots had issues with its speed and strength. Additionally, nearly every aircraft that launched at Cessna’s Delivery Center showed signs of stability issues right away. Even though the issue was solved later, the massive error wouldn’t soon be forgotten. In fact, of the initial 1,100 aircraft sold, less than 100 were reordered.

Cessna began working on a faster, improved 177 with the 177A in 1969. Powered with a 180-horsepower Lycoming O-360-E2D engine, the 177A still spent the next 10 years struggling with sales from and beyond the release of the 177B. However, Cessna’s development of the 177RG redeemed its namesake by increasing its speed with a 200-horsepower IO-360 engine, with the ability to rival the Piper Arrow and Mooney Ranger in the early 1970s.

Country of Origin: America

Cessna Cardinal 177 A/B

Below are the average statistics for the latest Cessna Cardinal 177 A and 177 B models. Find more information on Cessna’s Cardinal series by joining VREF Online .

Cessna Cardinal 177 A Statistics

Cessna cardinal 177 b statistics, operational resources, operations manual, maintenance document.

- 177A and 177B Service Manual

Local Resources

- Textron Aviation Inc. (Domestic and International Service Centers)

- Cessna Flyer Association

Manufacturer

- AOPA Insurance

- BWI Aviation Insurance

- Falcon Aviation Insurance

- Travers Aviation Insurance

- USAA Aircraft Insurance For Pilots

Cessna Cardinal 177 A/B Details

The following is information about the latest Cessna Cardinal 177 A/B.

Cessna’s 177A features a spacious back seat, more headroom, cigarette lighters, and signature red-accented panel control. It has a distinctly modern style called “fastback”, which Cessna’s marketing used in attention-grabbing headlines like “The Fastback Revolution”.

Cessna’s 177B features built-in lumbar seating designed with its contouring suspension system and optional adjustability features. This variation also has a separate baggage compartment and a T-style avionics panel.

This variation showcases a 180 horsepower increase while slots were added to the stabilator to improve landing. This variation is known for its wraparound windshields for ideal visibility, sharp leading-edge wings, and heavier nose design.

Wings on the later 177 series include a more blunt design to improve takeoff. This variation also has improved door sealing, optional 60-gallon fuel tanks, a 28-volt electrical system, a D-engine model update, and upgraded prop for higher continuous revolutions per minute (rpm).

- PS Engineering PMA 7000B-T Audio Panel/Intercom System (Bluetooth)

- Dual King KX 170B Navigation/Communications

- Dual Glideslopes

- King KCS 55A Compass System

- L3 Lynx NGT-9000 Multilink ADS-B In/Out Transponder with traffic display

- Northstar GPS-60 Navigator

- Davtron digital clock

- King KR 87 ADF

- King KN 64 DME

- Cessna 300 A Autopilot with ST-60 Altitude Hold, Vertical Speed, and Glideslope Coupling

- Eventide Argus 5000 Moving Map

- WX-10A Stormscope

- Shadin Digital Fuel Flow/Totalizer

- Electronics International UBG-16 Engine Analyzer with Burst Recorder

- Precise Flight Standby Vacuum System

- Pulselight Landing and Taxi Light System

- Garmin 3X GDU PFD Touch

- Garmin G-5 Standby

- Garmin GTN-750Txi

- Garmin GTR 225 Navigation/Communications

- Garmin GNX375 GPS WAAS ADS-B in and out

- Garmin GAD 29B

- Garmin GSU 25D ADAHRS

- Garmin GMA 340 Audio Panel

- Garmin GFC 500 Autopilot System

Specifications

- Take Off Run (50 ft.): 1,575 ft.

- Configuration: Single Engine, Piston, Fixed Gear

- Max Seats: 4

- Max Take-Off Weight: 2,500 lbs.

- Cruise: 130 kts

- Range: 535 nm

- Take Off Run: 750 ft.

- Landing Roll: 600 ft.

- Wing Span: 35 ft. 6 in.

- Length: 27 ft. 3 in.

- Height: 8 ft. 7 in.

Cessna Cardinal Models

In the mid-1960s, Cessna engineers sought to create a more modern version of the ever-famous 172. As a result, the original 177 went into production as a high-wing single-engine aircraft in late 1967 with a horsepower of 150.

Because the 177 was deemed an “underpowered” model, Cessna made adjustments. And in 1969, Cessna’s 177A appeared with an all-inclusive price of $16,995 and a power increase to 180 horsepower. This variation has a four-cylinder Lycoming O-360 engine with an improved cruise speed of 11 knots.

In 1970, Cessna welcomed the 177B into its 177 series. Major updates include a refreshed wing airfoil and a new constant-speed propeller. Cessna introduces a luxury version of the 177B in 1978 with leather upholstery, a table for the rear passengers, and a 28-volt electrical system.

The final 177 of the series introduced in 1970 is a retractable-gear 177RG Cardinal RG. Major changes from the 177B include a retractable nose-wheel and main wheels, with the nose-wheel enclosed by doors when pulled in. This variation is powered by a 200-horsepower Lycoming IO-360 engine and increased in maximum weight by 300 lbs. Cruise speed increased from the 177B by 148 knots.

Top Cessna Cardinal Questions

Check out FAQs about Cessna’s Cardinal.

Is Cessna Cardinal A Good Plane?

Cessna’s first of the 177 Cardinal series is known to be a slower aircraft with a decent but not tremendously exceptional range. After fixing notable issues, Cessna ended up with a decent plane in the 177RG. Outside of the 177, Cessna continues to see tremendous success selling its 172 and newer aircraft models.

How Much Is A Cessna Cardinal?

The cost of a Cessna Cardinal depends on the version. The estimated price for the 177 series according to its latest variation:

- 177 – $101,060

- 177A – $82,407

- 177B – $156,073

- 177RG – $153,266

Join VREF Online to keep an eye on future estimated aircraft prices.

How Fast Is A Cessna Cardinal RG?

A Cardinal RG has a maximum cruise speed of 180 mph or 156 kts. However, the recommended cruise speed is 171 mph or 148 kts.

Are There Any Incidents On The Cardinal’s Record?

According to the Aviation Safety Network’s database, 554 occurrences are on record. Of these incidents, 4 are notable – taking place from 1968 to 2003.

The grandson of a former U.S. Vice President, Alben Truitt, hijacked a 177 from Key West to Cuba in 1968, returning the aircraft nearly 4 months later. He was then charged with 40 combined years in prison for aircraft piracy and kidnapping.

In 1996, 7-year-old Jessica Dubroff, her certified flight instructor and father, took off in a 177B in an attempt to set a cross-country record for young pilots. However, the plane crashed after takeoff in Cheyenne, Wyoming killing everyone on board.

In 1998, a single pilot was flying a 177RG when it collided with another aircraft that had traveled off course with 14 people on board. Both aircraft crashed into Quiberon Bay off the coast of France, resulting in complete fatalities for everyone on board.

The young author of Wonder When You’ll Miss Me , Amanda Davis, and her parents crashed in a 177 shortly after takeoff. Amanda’s father, who was also chairman of the neurology department at Long Island’s Stony Brook University, was piloting the plane. According to news outlets, he lost control of the aircraft after he reported bad weather. This caused the 177 to crash into the mountainside, killing all on board.

Why Was The First Cardinal Engine A Failure?

The AOPA cites the Cardinal’s first engine as a misstep in design and manufacturing. The engine for this aircraft was too slow, which caused problems during takeoff and landing. One more specific problem initially reported is pilot-induced oscillation (PIO) or porpoising, which causes the aircraft to switch between upper and lower movements. It’s a control issue that Cessna fixed quickly with the launch of the 177A model.

Does Cessna Still Make The Cardinal?

Cessna ceased producing the Cardinal in 1978. While it was intended to replace the Cessna 172 Skyhawk, it was not successful. Even with its latest 177RG variation, sales slowed significantly. Only about 100 177s were made within its last year of production.

Join VREF Online For More About Cessna’s Cardinal Series

Join VREF Online for real-time data on thousands of single-engine aircraft, their turbocharged counterparts, and much more.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Related posts.

Cessna 152 Aerobat

Robinson Raven R44

2024 Flight Training & Pilot Program Growth

- Brands/Models

- Buyer’s Guide

- Glass Cockpits

- Auto-Pilots

- Legacy Instruments

- Instruments

- Safety Systems

- Portable Electronics

- Modifications

- Maintenance

- Partnerships

- Pilot Courses

- Plane & Pilot 2024 Photo Contest

- Past Contests

- Aviation Education Training

- Proficiency

- Free Newsletter

CESSNA 177 “CARDINAL CLASSIC”

By Plane and Pilot Updated January 28, 2016 Save Article

Don’t confuse the 1968 and 1969 Cardinal with the 1970 through 1973 models. The original 1968 Cardinal was powered by a 150-hp Lycoming engine. It soon became obvious that the 150 hp just couldn’t do the job, so a replacement 180-hp Lycoming was installed in 1969. Cessna made a major change on the Cardinal for 1970 with a revised airfoil that much improves lowspeed handling. The airplane also has a constant-speed propeller and cowl flaps, moving it out of the Skyhawk class and into the realm of the Skylane. It could be fitted with optional children’s jump seats and offered a range of more than 800 miles. The new wing allowed safe low-speed approaches, and the engine/prop combination yielded fine takeoff, climb, and go-around performance. The 1970 models replaced the earlier straight wingtips with drooping conical camber tips.

Related Stories

Boeing 737 200–900.

What‘s Going On with Cessna Denali Turboprop?

Daher TBM 940 Achieves Milestone

Stay in touch with Plane & Pilot

America’s owner-flown aircraft enthusiasts and active-pilot resource, delivered to your inbox!

Save Your Favorites

Already have an account? Sign in

Save This Article

- Search forums

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

- Pilot's Lounge

- Hangar Talk

Tell me about Cessna 177B's

- Thread starter N2124v

- Start date May 15, 2012

Line Up and Wait

- May 15, 2012

Ok, I am looking at buying a 177B. My main flights will be about 150nm, with some 350nm thrown in. I like the 177B for cruise speed (120kts), cabin space, and the engine. Are there any gotchas I need to look out for? Any advice? I've owned a mooney and 172's in the past, but want something different.

Touchdown! Greaser!

N2124v said: Ok, I am looking at buying a 177B. My main flights will be about 150nm, with some 350nm thrown in. I like the 177B for cruise speed (120kts), cabin space, and the engine. Are there any gotchas I need to look out for? Any advice? I've owned a mooney and 172's in the past, but want something different. Click to expand...

Final Approach

The Cardinals (especially 177B ) have wonderful handling. If you're used to a Mooney, landing a 177B should come naturally. They easily have the nicest roll response of any high-wing Cessna. The visibilty is fantastic for a high wing, and there's lots of spread-out room in the cabin. Not as much headroom as in a 172, however. Downside - the airframe seems a little tinnier than a 172. They used thinner exterior skins in some areas as a result of a weight-reduction campaign, and interior trim is typical '70s-era Cessna cheesy plastic. The nose gear is different from that of a 172, and seems to need maintenance a little more often. If it's a later 177B with the larger wheel and brake fairings, you may see cruise closer to 130 KTAS. The constant-speed prop and Lyc O-360 is a nice combination.

Pre-takeoff checklist

Nobody has mentioned it yet, and you might already know it, but if you are considering a Cardinal, you really should join Cardinal Fliers Online. They have a wealth of information about Cardinals, and a daily email digest that is particularly helpful, as well as some advertising listings. Their CFI, Guy Maher, is also an active agent for both buyers and sellers, and might be a good contact. Wells (former 177RG owner)

Taxi to Parking

Hemming, I want the gear down and welded. Just one less system to maintain (or break) since I'll be flying into a lot of little fields. Joining Cardnial Flyers is on my to do list, just seeing what others have to say. I really want a king air, but insurance would be a *****.... Thanks everyone.

Administrator

Cardinal's a nice bird.

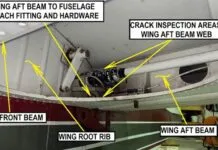

I love Cardinals. If you are serious about one make sure you ask the A&P who does your pre buy to carefully inspect the center spar which I understand can be prone to corrosion. But again there is something about that plane that just calls me.

- May 16, 2012

N2124v said: Hemming, I want the gear down and welded. Just one less system to maintain (or break) since I'll be flying into a lot of little fields. Joining Cardnial Flyers is on my to do list, just seeing what others have to say. I really want a king air, but insurance would be a *****.... Thanks everyone. Click to expand...

W. Stewart said: Nobody has mentioned it yet, and you might already know it, but if you are considering a Cardinal, you really should join Cardinal Fliers Online. They have a wealth of information about Cardinals, and a daily email digest that is particularly helpful, as well as some advertising listings. Their CFI, Guy Maher, is also an active agent for both buyers and sellers, and might be a good contact. Wells (former 177RG owner) Click to expand...

I just bought into a partnership of a 1976 177B (FG). So far, I love it for all the reasons noted above. For my money, it was hard to beat the price to performance ratio. I hired the guy from Cardinal Flyers to come down from Chicago to Indy check it out first. He's not an A & P, but he really knows the Cardinals, and what trouble spots to look for. The only thing I felt like I really took a risk on was the engine, but the engine was technically run out based on calendar date (although not total hours), and so I assumed that it would need a major overhaul in my analysis. Given the price of my interest, I felt like it was worth it even under that assumption, and any time I can get out of the engine is "found money." So far, the engine runs great, with plenty of power. The plane I bough into had not been flow much in years prior to my purchase. That is a red flag for engine corrosion. I am no expert, but I am told that that presents a higher risk that the cam lobes and lifters can become worn, thereby reducing the valve movement, and reducing power. You see symptoms of this wear not so much in reduction of top speed, but in fuel efficiency and climb rate. I understand that there can also be corrosion in the cylinders. I will let others more knowledgeable than me elaborate.

PPC1052 said: I just bought into a partnership of a 1976 177B (FG). So far, I love it for all the reasons noted above. For my money, it was hard to beat the price to performance ratio. I hired the guy from Cardinal Flyers to come down from Chicago to Indy check it out first. He's not an A & P, but he really knows the Cardinals, and what trouble spots to look for. The only thing I felt like I really took a risk on was the engine, but the engine was technically run out based on calendar date (although not total hours), and so I assumed that it would need a major overhaul in my analysis. Given the price of my interest, I felt like it was worth it even under that assumption, and any time I can get out of the engine is "found money." So far, the engine runs great, with plenty of power. The plane I bough into had not been flow much in years prior to my purchase. That is a red flag for engine corrosion. I am no expert, but I am told that that presents a higher risk that the cam lobes and lifters can become worn, thereby reducing the valve movement, and reducing power. You see symptoms of this wear not so much in reduction of top speed, but in fuel efficiency and climb rate. I understand that there can also be corrosion in the cylinders. I will let others more knowledgeable than me elaborate. Click to expand...

EdFred said: Tell that to my 32 years since OH with only 900 hour engine. Click to expand...

Tom-D said: If time has any effect on metal, why doesn't engine parts have a shelf life? Click to expand...

It's not just time, it's the chemical reactions that occur over time.

I just bought a Cardinal, and I really like it. Granted I have very little experience (32 hours), but it flies really nicely, makes good speed, and is a lot of fun to fly. The two things I was told to be very aware of on the inspection are: the crossover spare. Some corrosion might be ok, but if it needs to be replaced it is a deal killer, and the shimmy dampner, is different from a 172. If your mechanic doesn't know that and treats it like a 172 you will blow it out and have a several thousand dollare replacement. Like someone else said CFO is an incredible resource for the 177. -Dan

PPC1052 said: It's not just time, it's the chemical reactions that occur over time. Click to expand...

dell30rb said: And i'm guessing dirty engine oil will, over time have an effect on the rubber and other parts. Also long periods of sitting allows moisture and corrosion to work their magic. You don't have these issues with a part that is sealed in a plastic bag and coated with clean, protective oil. Click to expand...

EdFred said: True, but looking through the logs, even though the plane wasn't flown much for those 30 years, the oil got changed often. Click to expand...

PPC1052 said: That may be, and I really hope for the best with my plane, and yours too. I just mention it as an issue to consider. Low use doesn't automatically cause corrosion problems, but I understand that it often does. A purchaser should at least understand this and go in with eyes wide open. That was my only point. Click to expand...

Cardinal 177B is my third favorite "certified" plane I've flown. 2nd is a Cardinal RG.. 1st is the Grumman Tiger. Put a powerflow exhaust on it and get a little more efficiency out of it. Love the space, handling and visibility.

When you have to remove the wheel pants to clean the grass and dirt out of them, you'll wish you had the retract!

dell30rb said: When you have to remove the wheel pants to clean the grass and dirt out of them, you'll wish you had the retract! Click to expand...

I have owned a '74 177B for 4 years now. Good bird. If you've got young children or are getting older yourself, there really isn't a better plane. The big door makes getting car seats in and out so nice. Much easier for older people to sit on the seat and swing their legs in than most other planes as well. Here's a list of things I really like about the Cardinal - big doors - roomy interior and baggage area - great visibility (the wings sits back enough that you can see out in front of the leading edge and can see planes coming down on final while you're holding short of the runway and no lift strut to obstruct the view out when flying) - good handling and stall characteristics - very very hard to load the plane out of the cg envelope My Cardinal has just shy of 900lbs of useful load. With 360lbs of that being fuel when the 60 gallon tanks are full that leaves 540lbs or people and baggage. Some find that very adequate for their mission. We travel quite a bit in the plane and with our 2 kids growing we're finding 900lbs of useful load is not enough for us. The wing on the Cardinal isn't quite as good as some other Cessna's for short field performance. We regularly visit grass strips and the Cardinal does fine but you need to pay attention to your weight and the TO distances given in the POH. The climb performance isn't real good when fully loaded at higher altitudes but I don't have any other 180hp single experience with which to compare it. Be sure you have a thorough pre-buy inspection performed by an experienced Cardinal mechanic. I would recommend paying to have the headliner pulled down to properly inspect the carry thru spar. There have only been a few Cardinals that have had spar corrosion issues but you don't want to wind up the proud owner of one that does. It's a very costly repair. The CFO website has technical documentation from Cessna regarding the serviceable limits of the carry thru with regards to corrosion. There has been a white and silver 1970 177B for sale off and on for 5 or more years in Austin. I went to Austin to look at that plane when I was shopping for a Cardinal. The plane was opened up for annual when I looked at it and it was very rough. If you're looking at that plane I'd make sure you get a very thorough pre-buy done on it. It certainly wasn't a plane that met my standards. Good luck with your search. Feel free to PM if you have specific questions.

Doggtyred said: Cardinal 177B is my third favorite "certified" plane I've flown. 2nd is a Cardinal RG.. 1st is the Grumman Tiger. Click to expand...

EdFred said: Agreed. And luckily for me a lot of people thought that it did, and I got a steal of a deal. Click to expand...