The Spinoff

The Sunday Essay April 9, 2023

The sunday essay: the cancelled springbok tour of 1973.

- Share Story

Fifty years ago a rugby tour of New Zealand was scheduled. After loud and often rowdy protest against it, the tour was called off. Trevor Richards remembers the cancelled Springbok Tour of 1973.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

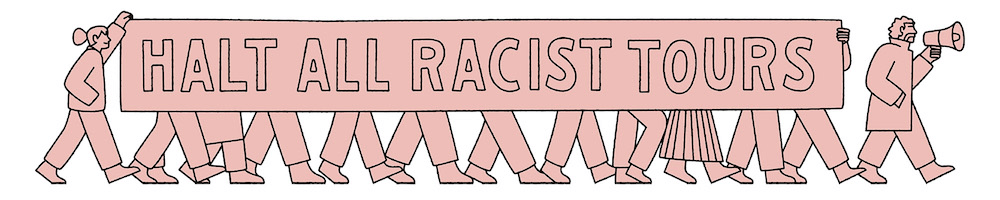

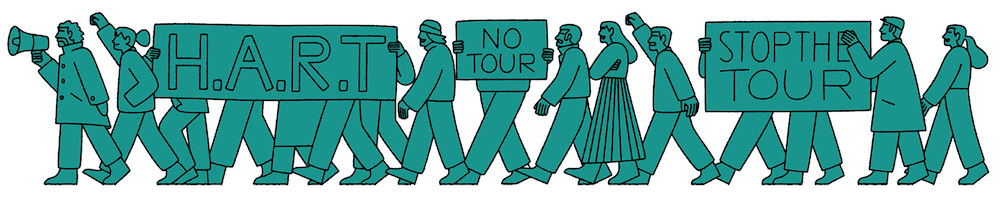

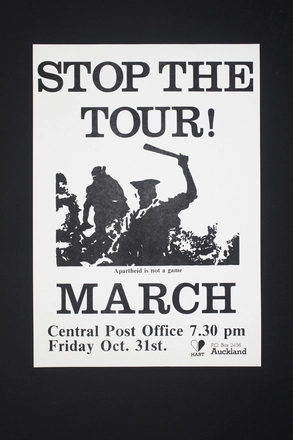

Illustrations by Joe Carrington

On April 10, 1973, then prime minister Norman Kirk told a crowded press conference that he had written to the New Zealand Rugby Football Union (NZRFU) advising that the government saw “no alternative, pending selection on a genuine merit basis”, to a postponement of the proposed Springbok tour to New Zealand.

Given the history of our rugby relationship with apartheid South Africa, the decision was somewhat surprising. Less than two decades earlier, the 1956 Springbok rugby tour had gripped the nation. Even the New Zealand Communist Party supported it, but by the late 1960s, times were changing.

New Zealanders were being confronted with a stark challenge. Eric Gowing, the Anglican Bishop of Auckland, was blunt: “What you think about sporting contacts with South Africa depends on what you think about racism.”

Whether the 1973 Springboks tour should proceed became a major issue. Its cancellation was an early indication that New Zealand was beginning to shed the rigid, conservative, “rugby, racing and beer” assimilationist values of the post World War II era.

At the time, New Zealanders were well aware of protesters’ commitment to disrupt the tour should it proceed. Almost none were aware of the behind the scenes “dialogue” between the prime minister Kirk and the leadership of the Halt All Racist Tours movement (HART) leading up to the tour’s cancellation.

HART had been formed in 1969 to stop the 1970 All Black tour of South Africa. Looking back, we were Pollyanna at the barricades. Our 1970 strategy had been based on the assumption that those in positions of power – the government and the NZRFU – could be influenced by facts, logic and morality. What we discovered was that prejudice and self-interest were immune to such appeals. A new approach was needed.

By the end of March 1971, HART and CARE (the Citizens’ Association for Racial Equality) had announced policies of “non-violent disruption” of apartheid sport. Mr Niceguy was just too easy to ignore. There needed to be the promise of a frontal attack on such tours.

While policies of direct action are what HART and CARE were best known for, most of our time and money was spent on education. Hundreds of thousands of leaflets were distributed. We published a monthly tabloid newspaper. Meetings were held in draughty halls up and down the country. Between March 1971 and February 1973, five overseas speakers toured New Zealand.

The 1972 general election campaign did not fill anti-apartheid hearts with any great confidence. The ruling National Party declared its support for the tour. Although the opposition Labour Party did its best to avoid the issue, leader Norman Kirk promised not to stop the tour. On November 25, twelve years of National Party rule came to an end. Labour was elected with a whopping 23-seat majority. What would the new government do?

On January 3, 1973, the Supreme Council for Sport in Africa (SCSA), the body which coordinated and promoted Africa’s anti-apartheid sports policies, called on all Commonwealth countries in Africa to withdraw from participating in the 1974 Christchurch Commonwealth Games if the Springbok tour went ahead. It was New Zealand’s first direct taste of the strength of independent Africa’s opposition to apartheid.

On January 23, the new prime minister sent the NZRFU a letter, attaching a report on the implications of the tour for New Zealand’s international standing, for internal race relations and for law and order. The report concluded: “it is the considered police view that the tour would engender the greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known.” On the international front, the report said there was “a virtual certainty that the Commonwealth Games would … either have to be cancelled or be a failure.” Serious concerns were expressed about the tour’s potential impact on race relations.

Margaret Hayward, Kirk’s Private Secretary, wrote in Diary of the Kirk Years that “the prime minister is optimistic. He appeared to believe that if the rugby union was treated like a group of responsible men, they were more likely to act like reasonable men.” If he had a concern, it was about anti-apartheid groups.

At the end of January, his message to an anti-apartheid deputation had been to “cool it”. We could understand his logic. If he was going to stop the tour, he could not be seen to be giving in to pressure from HART and CARE. But the “if” was a very big one. Labour’s election promise not to cancel the tour sat front and centre in our minds.

In early February, following a meeting to consider the prime minister’s letter, the Rugby Union announced that “arrangements for the tour are proceeding”. When a radio journalist asked if this was the union’s last word on the tour, NZRFU chairman Jack Sullivan smothered the microphone “with a big fist”. New Zealand’s rugby authorities in 1973 were men who fondly remembered the 1956 tour. The NZRFU was never of its own volition going to stop the tour.

Stories in the daily metropolitan press started speculating that the tour might be stopped “in the public interest”. I didn’t believe it.

In the second week of February, HART issued a comprehensive statement outlining what it would do if the tour proceeded. “Let everyone know that … the whole of New Zealand will have to be guarded on a 24 hour a day, seven days a week basis.” Many papers accorded it front-page lead status.

The statement infuriated rugby supporters. The prime minister issued an angry statement: “Richards, you are not running the country.” The police announced that they were considering prosecuting me for the statement. Some leading figures within the movement considered that I had overstepped the mark. Sometimes, it could feel a bit lonely.

At a HART meeting in Ashburton a few days later, around 600 pro-tour supporters turned out in an effort to prevent me from speaking. The meeting went ahead, but only after a number of their placards had come crashing down on my head.

Privately, the PM was remaining optimistic. Hayward wrote in her diary: “Everyone else seems to be making moves, but Mr. K remains quietly confident. He just grins and tells us he’s moving with ‘dynamic caution’.”

In mid February the Rugby Union met with the prime minister. Kirk’s concerns were ignored. The NZRFU announced the tour was proceeding. Asked what the government’s next step would be, Kirk said “wait and see I guess”. Asked to be more specific about timing, he said “soon, in the soonest sense of soon”. By now, most political commentators were of the view that Kirk would cancel the tour. We could see no evidence for this.

At the end of February, the prime minister met with a deputation from the pro-tour lobby. Some time later, a full transcript of the meeting fell off the back of a truck and into HART’s hands. The prime minister had told the delegation that his decision on the tour must be based only on one fact and that was what is in the best interests of New Zealand. “There is no evidence that I can find,” he said, “that supports in any way the continuation of the tour.”

Frank Corner, secretary of foreign affairs and head of the prime minister’s department, was later to say “the tour did not fit in with Kirk’s view of what New Zealand should do in the world, and what it’s standing would be should the tour proceed.”

Around this time, I was contacted by Bob Scott, an Anglican minister and director of the Wellington Inner City Ministry. He had just met with Norman Kirk. The prime minister’s view, which Kirk wanted relayed to HART, was that the job of the anti-apartheid movement was to be calm and quiet. The government believed that our views were well-known, and the ball game was now being played on a different field – theirs. For the next six weeks, until the tour’s cancellation, Scott acted as go-between for the prime minister and HART.

At the same time, Southern Māori MP, Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan contacted me with a similar message. The prime minister was clearly leaving nothing to chance in getting his message through to us. She assured me that Kirk would act. But the doubts and concerns we had were both real and multiplying. Over the next six weeks, as Scott played out his go-between role, the single question exercising the minds of all in HART’s national leadership was whether or not Scott’s assessment of the prime minister’s intentions could be trusted.

By the beginning of March, those opposed to the tour split into two broad groups. One faction, which aligned with the Labour Party, trusted the prime minister to deliver, and were opposed to HART and CARE being too critical of the government. Others believed that all social democrats were untrustworthy and urged more radical action.

In early March, Bob Scott attended a HART national council meeting. For about an hour, he argued that Kirk could be trusted, and we needed to stay calm. The meeting agreed to what Kirk wanted. We would keep a low profile until the end of the month, but we did so with considerable misgivings. What exactly did “soon, in the soonest sense of soon” mean? It sounded just too glib.

Sharpeville Day, March 21, 1973, saw leafleting, picketing, vigils, a rock concert, marches, rallies and commemorative services throughout the country. We publicised recent messages of support from diverse groups and individuals, including former UN secretary general U Thant and the Anglican Bishop of Woolwich and former MCC cricketer, David Sheppard. The most militant action taken was by members of the New Zealand Seamen’s Union, who stopped work for 24 hours to demonstrate their opposition to apartheid.

After Sharpeville Day, tensions escalated significantly. At the end of March, I was in Dunedin for an anti-apartheid meeting. Scott was also there. I reminded him that our agreement with Kirk was about to expire. Scott indicated that he, too, was concerned with how slow the prime minister was moving. He undertook to contact Kirk.

Towards the end of the first week in April, Scott contacted me. “Early early next week,” I was told. I was fed up. At the beginning of March we had agreed to what the prime minister had asked. We had sat on our hands for a month, and marked time. Now we were being told to wait until mid April. What would we be told then? That the tour was on and that I and others were to be prosecuted? By now, the common view in the HART leadership was that Scott was being taken in by the prime minister, and that we were being taken in by Scott.

It was not just an issue of what the HART leadership was thinking. What about our supporters? We at least knew more or less what was going on between ourselves and the prime minister. Most of our supporters did not. They were becoming increasingly restless. It was easy for some of them to regard the HART leadership as just a bunch of media freaks who had got cold feet.

If we could not control events we at least needed to be singing our own song instead of being in a chorus singing someone else’s tune. A meeting was planned in Wellington for Sunday, April 8. Most of the HART leadership was there. All of us believed, with different degrees of conviction, that the tour was on. In about three months, the Springboks would be here. We needed to start planning and organising for their arrival.

We never got to do that. There was a knock at the door. In walked Bob Scott, who had not been invited to the meeting. A silent sigh ran around the room. How many more days were we going to be told we had to wait? “It’s near its conclusion,” he said. “Just wait a few more days.”

“You keep saying that – a few more days, a few more days,” we replied. Some in the room were adamant one day was a day too long to wait. Others, outside of HART, were clearly thinking the same. That night, a rugby grandstand in Papakura was burnt to the ground.

I sat and listened. I wanted to believe Scott, but ever since he had started acting as go-between, it felt as if we were all players in an updated version of Waiting for Godot. If it came to a vote (which it wouldn’t – most decisions were arrived at through consensus), I would not go with the “just wait a few more days” line.

Towards the end of the meeting, Scott signalled to me as he left the room and I followed. “If I tell you something, will you go back inside and tell them?” he asked. Half a dozen qualified responses flashed through my head. This wasn’t a time for a philosophical discourse on the nature of loyalty, trust or honesty. “No,” I responded, and hoped I would be able to keep my word.

“I spoke with the prime minister yesterday,” he said. “The tour is off.” I must’ve looked unconvinced. “He has written to the Rugby Union requiring the tour be called off.” And then he repeated, “It’s off. The letter has gone to the NZRFU. They have it. Mr Kirk will make the announcement next week.” I believed him.

I went back into the meeting, which was by now grudgingly of the view that we would extend the contract with Kirk and “hold off” for another week. No one asked me what Scott had wanted to tell me but I was asked for my view on how we should proceed. I spoke briefly, positively endorsing the emerging consensus.

I got a ride down to the airport. As we twisted down Mount Victoria, I had great surges of excitement. It was off! The tour was off! The joy was pure, immense, uncomplicated. I felt like a kid at Christmas. The flight back to Christchurch was fairly empty. A flight attendant came and chatted for a few minutes. How was I? Did I think the tour would be called off? I gave the standard response, but inwardly, my smile was so large I feared it might take over my face.

Looking back at the 1970s, the cancellation of the 1973 Springbok tour was part of a brief, exhilarating, period in our politics. If I had to name my favourite year, it would probably be 1973. I was 27, and after 12 years of conservative government, change was on its way.

Trevor Richards was national chairperson of the Halt All Racist Tours movement (HART) from 1969-80, and international secretary from 1980-85.

Search form

- Send Us Your News

- Wedding Guide

- Death Notices

- Privacy Policy

- Drive South

- Media Council Complaints

The forgotten Springbok tour might be the most important

You are not permitted to download, save or email this image. Visit image gallery to purchase the image.

Many people remember the 1981 Springbok tour. Over 56 days, the tour brought the country the closest it had come in the 20th century to civil war.

Fewer people recall the 1976 All Black tour of South Africa. That tour had gone ahead with the blessing and goodwill of the New Zealand government. No other government in the world had offered apartheid South Africa such enthusiastic support.

Countries felt compelled to act. The International Olympic Committee was asked to ban New Zealand from the 1976 Montreal Olympics. The IOC refused.

With the All Blacks still in South Africa, about 30 countries walked out of the Olympics in protest at New Zealand’s presence. The first major boycott of the modern Olympics was caused, not by US-Soviet Cold War rivalries — those boycotts were to come later — but by New Zealand’s support for apartheid.

In 1985, two lawyers brought a case in the High Court which led to an injunction being issued which prevented that year’s All Black tour of South Africa taking place. I am not sure how well remembered that campaign is.

And the cancelled 1973 tour? Today, few know anything much about it. It is the forgotten campaign.

The tours of 1981 and to a lesser extent, 1976, are better recalled, largely because their dreadful outcomes were hard to ignore. The events of 1973 go mostly unnoticed, buried by the dramas of 1976 and 1981. Yet to this activist/student of history — and there’s a potential conflict if ever there was one — the campaign against the 1973 tour was the most significant campaign of them all.

In early 1971 Hart had announced its intention to disrupt the 1973 tour, should it proceed. The reaction of many, especially in provincial and rural New Zealand, was hostile. In February 1973, during a South Island speaking tour, there were foretastes of what was to come in 1981. In Ashburton, about 600 pro-tour supporters had turned out in an effort to prevent me from addressing a meeting. The meeting went ahead, but only after a number of their placards had come crashing down on my head.

In demanding the cancellation of the tour, Hart was openly challenging the values of post World War 2 New Zealand. Then, we were a predominantly rural, male-dominated, conservative society whose Pakeha citizens — well, most of them — believed the country had "the best race relations in the world". Many saw New Zealand as part of a white man’s club which had more or less ruled the world for as long as most people could remember.

These old values were slowly dying, but in 1973 they still possessed a lot of clout. Perhaps no single person better encapsulated them than Tom Pearce, former president of the New Zealand Rugby Football Union and the manager of the 1960 All Blacks in South Africa. In April 1972 he had said "where the white man has been, he has brought law and the establishment of his regime for the benefit of mankind. If these go, we are lost ... They say if we have a Springboks tour, we won’t have a Commonwealth Games — I couldn’t give a damn".

Prime minister Norman Kirk’s decision to stop the 1973 Springboks rugby tour caused an uproar. Organisations supporting the tour threatened "massive retaliation". Rugby Weekly’s front page headline read: "In memory of the grievous harm suffered by a great game at the hands of politicians, international blackmailers and rabble-rousers".

During the 1972 general election, Labour had promised it would not stop the tour. Announcing the abandonment of the tour less than six months later, Kirk said: "I have no doubt that I will be criticised because of the difference in what I said last year, and what I said this year. When it comes to a decision between what I must do in the light of the facts that are put before me in the interest of the country, and a desire to avoid criticism, then I would be failing in my duty if I did not accept the criticism and do what I believe to be right."

Kirk was concerned that if the tour proceeded, African nations would stay away from the 1974 Christchurch Commonwealth Games. He had also received advice from the police that were the tour to proceed, it would engender the greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known. But these were not his major concerns.

Frank Corner, secretary of foreign affairs during Kirk’s prime ministership, has said that "Kirk could see that if he stopped the tour, Labour could lose the next election. But the tour did not fit in with his view of what New Zealand should do in the world, and what its standing would be should it proceed".

It was probably the first time a New Zealand government had sought to change both the way New Zealand viewed itself and the way it wished to present itself to the world.

There would seem to be little doubt that the driving force behind the tour’s abandonment was the prime minister himself. At a Commonwealth finance ministers meeting in Dar es Salaam in September 1973, Bill Rudman was one of a small group of expatriate New Zealanders meeting New Zealand finance minister Bill Rowling. Rudman congratulated Rowling on the government’s decision to stop the Springbok tour. Rowling’s response took Rudman by surprise. That, Rowling said somewhat sniffily, was Mr Kirk’s decision.

Of the four major post-1960 New Zealand battles against apartheid sport — 1973, 1976, 1981 and 1985 — it was the outcome of the 1973 battle which was arguably the most historically significant. It was the cancellation of this tour which heralded the beginning of New Zealand’s gradual shift into a more progressive space.

Related Stories

Opinion: Budget a 'mixed bag' for disabled people

Is our uni going out of fashion?

Happy Christmas, war is over. But has another started?

Cartoonist’s view — Yeo

Letters to the Editor: violence, wisdom and justice

Considering the wrecking of a legacy in just a few months

Rishi may have wanted to end agony

Cartoonist's view - Yeo

Letters to Editor: hospital, bus hub, railways

Willis pulls a skinny rabbit out of the hat

Does New Zealand still have Ardern’s political capital to spend?

Opinion: Budget 'a difficult balance'

Words: Neil Reid Design: Paul Slater

The last apartheid-era Springbok rugby team landed in New Zealand 40 years ago, on July 19 1981. In the 500 days leading up to the South African team’s arrival the anti-tour movement predicted blood would be spilt around the country, while a pro-tour MP claimed the police could handle whatever awaited “with their eyes closed”. Neil Reid unravels the complex build-up to a sports tour that made history and shows how one of those bold claims turned out to be true.

Food wasn’t the only thing on the menu as members of Halt All Racist Tours (HART) met for dinner on the night of November 3, 1979.

Those in attendance gathered for a night celebrating the 10th anniversary of the movement opposed to all rugby tours to and from South Africa.

They toasted the group’s biggest victory to date; defeating a proposed 1973 Springbok tour of New Zealand, which was ultimately prohibited by then Prime Minister Norman Kirk.

But it certainly wasn’t a case of ‘job done’ as members officially launched a 500-day campaign to stop the Boks’ proposed 1981 tour of New Zealand.

At that stage the New Zealand Rugby Union (NZRU) hadn’t formally invited the Springboks to tour. But it was rugby’s worst kept secret that that procedural step was a matter of when, not if.

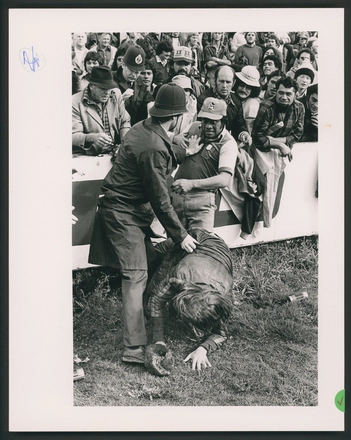

Protestors in the minutes before violent clashes around Eden Park on the day of the third All Black / Springbok test. Photo / NZME

As early as March 1980 – 16 months before the team flew into the country, starting 56-days of civil turmoil – the Robert Muldoon-headed Government was pressured to take several steps to stop the tour, including withholding entry visas.

Within a month the Auckland Rugby Union, chaired by staunch pro-tour advocate Ron Don, had gone public with its support of a tour. At the same time nationwide protests hit the streets around New Zealand.

They were small at first; about 30 attended one down Queen St on April 12 – walking behind actors dressed as All Blacks, roped together and led by rings through their paper noses by a duo of mock Springboks. On the same night about 50 protestors gathered outside the NZRU headquarters in Wellington.

On April 18 Don made an impassioned plea during the union’s annual general meeting in the same building for the tour to go ahead.

Don – whose Auckland home was later peppered with a shotgun blast – told fellow delegates they had a “duty to the people who elect us, and the rugby people of New Zealand want the Springboks to tour here in 1981.

“Let us forget the humbug and hypocrisy of the politicians and stick to our job of promoting rugby”.

He added that instead of taking aim solely at South Africa, those opposing the tour should “press similar concern for the rampant racial discrimination in the United States and Australia, just to name two countries with which we are closely associated”.

NZRU boss Ces Blazey cited an early poll which showed just 34 per cent opposition to the tour in pushing for the Springboks to tour. Photo / File

The NZRU had previously been presented with a letter from Minister of Foreign Affairs Brian Talboys that under the Gleneagles Agreement – signed in 1977 by Commonwealth prime ministers and presidents pledging their support against apartheid – that he was “deeply concerned” that the tour might go ahead.

Around the same time HART went public with appeals for donations, saying they hoped to raise at least $50,000 to help fight the tour.

At that stage public support seemed to be growing for the tour. Just 34 per cent of respondents to a New Zealand Herald-National Research Bureau survey said they were opposed.

NZRU chairman Ces Blazey described the poll result as “very useful” for the rugby union.

The Te Tai Tokerau District Māori Council offered majority support for the tour, with one member saying it would provide a chance to show the Springboks how Māori and Pākeha lived in union.

The Young Nats also did a U-turn on an earlier mooted remit urging the NZRU not to invite the Boks here, by saying South Africa was also a trading partner.

“Purely a sporting manner”

September 12 is a day of infamy in the anti-apartheid movement, especially in New Zealand.

It was the day in 1977 when anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko was beaten to death by police in a Port Elizabeth cell.

In 1980 it also became the date when the NZRU formally extended its tour invitation to the South African Rugby Board (SARB). The following year September 12 was the date of the third and final test in the All Black-Springbok series; scene of the most violent and shocking of all protest clashes.

In explaining the 1980 invitation Blazey released a lengthy statement saying the SARB was breaking down racial barriers; five of its seven national team selectors were non-white, mixed trials were held for all national teams and “any player in South Africa can progress to the highest level of his potential”.

South African rugby supremo Dr Danie Craven would describe the NZRU’s invitation for the Springboks to tour as a sign “sport and rugby reigns supreme”. Photo / Getty Images

Blazey said it was now up to rugby officials to convince “the people that matter that the invitation has got nothing to do with political issues at all and is purely a sporting matter”.

He said it was inevitable there would be “differences of opinion” regarding the tour, pointing to two polls which showed support for the tour, including the NZ Herald-National Research Bureau survey.

Blazey added: “We continue to believe that sporting boycotts are undesirable and also unfair to the young people who participate in sport. Accordingly, we cannot support them”.

More than 11,500km away in Stellenbosch, SARB president Dr Danie Craven said the invite showed how the “spirit of sport and rugby reigns supreme”. “We admire the people who breathe this spirit.”

The invitation for the Springboks to tour New Zealand was issued on the third anniversary of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko’s death in a South African police cell. Photo Associated Press

But closer to home, the reaction to the invitation wasn’t welcomed by an ever-growing moment against the tour.

Talboys said the decision was disappointing, but again reaffirmed the Government’s stance that it wouldn’t move to stop the tour.

He added rugby bosses would now bear a “heavy responsibility” and that the Government had tried to persuade the NZRU not to go ahead with the sporting contest that “is not in New Zealand’s best interests”.

The leader of the Opposition, Bill Rowling, described the NZRU’s stance as “totally irresponsible” and said the sporting body had “acted in a completely selfish manner”.

The Citizens Association for Racial Equality (CARE) was outraged, prophetically saying it would “split New Zealand down the middle”.

John Minto, the national organiser of fellow anti-tour group HART, also correctly stated that New Zealanders would now be “out in the streets in protest” in big numbers. But history shows his claims HART and other anti-tour protestors would stop the tour taking place was wrong.

The invitation was issued just two days before the All Blacks played Fiji at Eden Park. Don said the venue would be guarded by additional security “from this moment on” due to threats of damage from protestors.

The 1981 Springbok tour divided the country and saw New Zealanders clash with terrible consequences. Photo / NZME

The increase in opposition to the tour was evident in a Heylen poll released just four days after the official invitation.

It showed just 30 per cent of respondents supported the tour; down from a previous poll where 57 per cent backed it. Forty-six per cent said they were opposed.

Those who started to speak out included the headmaster of Auckland Grammar School John Graham, who had captained the All Blacks in some matches of their 1960 tour of South Africa. Graham said he was opposed to apartheid and the best way to show that was to ostracize South Africa.

Police could cope “with their eyes closed”

Invercargill MP Norman Jones was dubbed the ‘Mouth of the South’ for his outspoken stance on a variety of issues during his Parliamentary tenure from 1975-87.

But one quote from the former National MP – who lost his right leg at the age of 19 after being hit by tank fire during World War II – certainly didn’t age well.

In late September 1980, Auckland Central MP Richard Prebble sought an assurance in Parliament from police minister Ben Couch that the police would be able to handle any attempts to disrupt the tour.

Before Couch had a chance to answer, Jones interjected and told the debating chamber that police would be able to “do it with their eyes closed”.

Just a day after Jones’ comment, the police’s stance towards the protest movement was placed firmly in the public’s eye.

Couch received a complaint that police had treated protestors unfairly during two incidents at Eden Park. It said officers turned a blind eye to rugby fans confronting protestors and that a fan had covered a protestor in paint in front of officers and then slashed protest banners with a screwdriver.

After several anti-tour protestors were evicted from Eden Park during an Auckland-Canterbury clash, anti-tour groups claimed police were “working blatantly in concert” with the Auckland Rugby Union.

Minto also claimed the police appeared not to be impartial and were “grossly exceeding their powers”.

Amid the increasing criticism of police actions, Couch incredibly told Parliament he wanted to keep the police “right out” of the tour to prevent them becoming “the meat in the sandwich of opposing views”.

Labour MP and future Hutt City mayor John Terris correctly predicted “blood” would be spilt if the Springbok tour went ahead. Photo / NZME

That was never going to happen. Much closer to the mark was a dire prediction from Labour MP John Terris.

In the same debate, Terris warned: “If this tour goes ahead, there will be blood – New Zealanders’ blood – spilt on every rugby field in the country”.

Terris also asked Parliament if it was right that the tour was going to “allow racial division to sour relations between cultures here?”.

In early December, the NZRU formally confirmed the schedule for the Boks’ 16-match tour.

Blazey said just one rugby club had told the union it would not allow the Boks to use their facilities for training purposes.

Questions were also raised over whether union members at hotels to be booked for the Springboks would refuse to serve them or clean their rooms. Amid the uncertainty, the ‘Mouth of the South’ again made headlines, offering to billet players when in Invercargill for their clash against Southland.

As 1980 drew to a close, Muldoon revealed that the cost of the police operation to handle the Springbok tour could be as high as $2.7 million.

It was a sum the Prime Minister said he was “not happy about”, but he then added: “We’ve said we must have law and order and if the tour goes ahead then we have no option but to incur those costs”.

Muldoon said he had told Blazey and the NZRU about the predicted “very substantial cost” and the union still “decided to go ahead”.

Couch predicted - in a comment he may have come to regret - that it was unlikely police officers would be seen at match venues in riot gear.

Rather optimistically, he also said the tour operation might not even need half of the officers set aside at that stage to control any off-field issues.

Rugby bosses “may not know what has hit them”

By the time 1981 arrived, the protest movement was already incensed by the staunch pro-tour utterings of Don.

He stirred up more anger on his return to New Zealand in late January after holidaying in South Africa and Namibia for three weeks with his wife.

Don first repeated a comment from South Africa Prime Minister P. W. Botha challenging anyone in the world to establish non-whites of South Africa “were worse off than the non-whites of any country on the African continent”.

The police Red Squad takes guard outside the Springboks’ tour bus in Nelson. Photo / NZME

Don went on to say: “There is starvation in many parts of Africa. There is no starvation in South Africa”.

He again took aim at anti-tour protestors, saying: “Are we not as New Zealanders in danger of having our country run by minority groups?

“I am all for the right of people to hold differing opinions. But I am all for the majority, too. And it is my belief that a majority of New Zealanders want the Springboks to tour.”

But just six days after another optimistic pro-tour delivery from Don, a leading rugby official from across the Tasman provided a reality check of what lay ahead.

Australian Rugby Union treasurer John Howard spoke to the New Zealand Herald about the turbulent 1971 tour by the Boks of Australia. Howard’s role in the tour included logistics around security and travel.

Violent protests followed the Springboks around Australia. Howard said abusive phone calls to rugby officials included threats of death and physical violence.

“Any officials connected with the tour in New Zealand will find they will have to use every waking moment to being absolutely determined that the tour will go on,” he said.

“The strain and the tension are enormous and it doesn't let up. They will experience things they have never before experienced in their rugby lives.”

Howard said his “deepest memory” of the tour had been the estimated 1400 police officers employed to protect law and order during a test at the Sydney Cricket Ground.

Fears of violent conflict off the field played out throughout New Zealand during the 1981 tour from hell. Photo / NZME

Don wasn’t the only pro-tour protagonist to visit South Africa in early 1981. So too did Hauraki MP Leo Schultz.

The National MP said after his three-week holiday there that he believed a lack of interest from black people in wanting to play at the top level – and not selection bias – was the reason why the Springboks had never had a non-white test player.

He said rugby fields created in Soweto were used for other sports.

And speaking on the political situation there, he stated: “I do not believe South Africa is quite ready for black majority rule, even though that is desirable. Majority rule will come as generations go by and more black people are ready to accept the responsibility.”

While Schultz spoke of his support for the tour to go ahead, Muldoon made his strongest comments to date on March 10, going public with his view that it should be cancelled.

Muldoon said he believed a “majority” of New Zealanders were opposed to the tour, both in protest against apartheid and also from fear of potential civil unrest.

He said he didn’t believe the tour would aid his National Party’s hopes of re-election later in the year, despite claims from critics that it would shore up National's vote in key marginal provincial seats.

“My personal view is that whatever happens in the context of the Springbok tour is more likely than not to damage the chances of the Government.”

Outspoken rugby official Ron Don, left, labelled the protest movement as “minority groups” and “communist inspired”. Former All Black captain and coach Sir Fred Allen, right, feared “innocent bystanders” could be harmed during protests. Photo / NZPA

While Muldoon’s Government continued its stance of not refusing entry visas for the Springboks, it did show its displeasure by rejecting an NZRU grant for $10,000 to help with coaching programmes.

The Bok tour was understandably a hot topic at the NZRU’s annual general meeting on April 9.

On the eve of the gathering of rugby administrators, Don kept up his attack on the protest movement, describing it as “communist inspired”.

And Blazey told delegates that by inviting the Springboks here, the NZRU was “carrying out our responsibility as rugby administrators”. He said all 26 provinces supported the tour and added: “We will not make decisions based on threats either from within New Zealand or overseas”.

“Protestors . . . had better look out”

Tickets for the scheduled 16 matches were released on April 22.

For the first time in New Zealand rugby history they contained a raft of security-based restrictions. Fans had to agree to be searched on entry. Items such as banners, placards, flags, poles, fireworks, loudhailers and “any article that might impede the match” were banned.

An injured female anti-tour protestor is comforted after being attacked by rugby fans outside Rugby Park, Hamilton, after the tourist’s clash with Waikato was cancelled. Photo / NZME

Those who ignored the regulations faced being trespassed, a fine of up to $1000 and a potential three-month prison term.

The Auckland Council for Civil Liberties branded the move as “arrogance” and claimed it showed rugby officials were overstepping their rights.

Former National MP Bill Tolhurst confirmed he had secured tickets for Wanganui’s clash with the tourists on August 5 and issued a strong warning to anyone who impacted on his viewing enjoyment.

“I will be going to the Springbok match in Whanganui and if protestors and others interfere with my enjoyment of the game they had better look out,” Tolhurst said.

He believed the tour would go ahead with “little if any” disruptions because so many New Zealanders enjoyed rugby “and to them this is a far greater religion than politics or the church”.

Tolhurst was correct that rugby had a huge support base in New Zealand, but he was wildly off the mark in terms of the growing determination of the anti-tour movement.

Just under two months before the Springboks were set to arrive, tens of thousands took to the streets in a series of marches around the country.

Brutal memories of the Soweto massacre, where students and others were shot dead by South African police, were frequently aired at anti-tour protests. Photo / Getty Images

That included 12,000 who marched up Queen St, with well-known trade unionist Syd Jackson telling the gathering: “This is only the beginning”.

In the lead-up to the protest, a group of Auckland University students – including future Green Party MP Kevin Hague – set up camp in the university’s quad and went on a hunger strike.

A week later about 1200 attended a pro-tour event at Auckland’s Aotea Square, where a speaker described HART as a “front for the Communist Party”.

Another protest at Aotea Square saw students from Auckland University and Auckland Metropolitan College re-enact the 1976 Soweto massacre, where at least 176 people were shot dead by South African police.

As the size and regularity of anti-tour protests increased, police revealed more details about their own planning for ‘Operation Rugby’.

That included confirmation that 3600 police – about 73 per cent of sworn officers – would be used specifically during the tour.

The elite police Red Squad unit formed to protect the Springboks undertook riot control training at the SAS’ Auckland base. Photo / Mike Scott

The police also confirmed the creation of two special groups – Red Squad and Blue Squad – who would escort the Springboks and also be trained and equipped for serious unrest.

Red Squad was trained at the SAS base in Papakura. Requests to a police photographer for the release of training pictures was denied as “the sight and noise of a police flying wedge and other tactics is not pretty”.

“The rule of law must prevail”

Less than a month before the Springboks were set to fly into New Zealand, Parliament voted through a motion calling on the NZRU to “reconsider” the tour invitation.

The resolution also called on any future protests “to be undertaken in a peaceful manner in full acceptance of the fact that the rule of law must prevail”.

MPs opposed to the tour were left outraged, claiming National had buckled in not backing the earlier proposed wording, which asked rugby bosses to “withdraw” the invitation.

New Zealand Prime Minister Rob Muldoon was open about his frustrations over the cost to the tax-payer of policing the tour, but would not step in to block visas for the Springboks. Photo / NZME

Not surprisingly, the NZRU did not budge after the joint political message.

It also stood firm after a “last attempt” from Muldoon – delivered live to the nation via a TV and radio broadcast – for them to reconsider.

Muldoon stated: “I am making this approach on television rather than behind closed doors in my own office or in the boardroom of the rugby union council because I want all the people of New Zealand to know exactly what I have said”.

Muldoon spoke again of New Zealand’s obligations under the Gleneagles agreement, and how our country abhorred apartheid and racial discrimination.

He concluded by saying: “As to the tour, the issue now rests with the New Zealand Rugby Union. I say to them, think well before you make your decision”.

The Springbok touring squad applied for their visas on July 1.

Two days later huge protest marches were held in 30 towns and cities around New Zealand, including about 30,000 marching through central Auckland.

A unified cry of “One, Two, Three Four . . . We don’t want your racist tour” boomed out during all the marches.

Meanwhile, in Gisborne – venue of the tour opening clash against Poverty Bay on July 22 – Rugby Park was under 24-hour guard against any acts of vandalism.

Those who volunteered their time for shifts included former All Black captain Ian Kirkpatrick, who toured South Africa in 1970.

While some sections of the local community were preparing to lay out the welcome mat for the Springboks, a local council spokesman said officials were “very apprehensive” over potential violent clashes.

Gisborne mayor and former All Black Tiny White, pictured right, went as far as saying he was “praying that they [the Springboks] do not come. I am strongly opposed to the tour”.

Meanwhile, trainee nurses were being rostered on to work in Gisborne Hospital in case they were required.

Fears of violence around the country had been renewed after comments from HART chairwoman Pauline McKay that New Zealand was about to go through two months of “things we never believed could happen”.

The head of ‘Operation Rugby’, Chief Superintendent Brian Davies described the comment as “setting the scene for a violent confrontation.”.

Even more concerning was the release of leaflets from a hardcore section of anti-tour protestors describing how to make petrol bombs.

The Springboks finally flew into New Zealand on July 19.

Waiting for them on and around the tarmac at Auckland International Airport was a large police presence.

So too were scores of protestors.

John Minto with a picture of the crowd invasion at Rugby Park which caused the cancellation of the Springboks’ clash with Waikato in 1981. Photo / NZME

It was impossible for the Springboks to miss either grouping. And that was the case for the next 55 days to come, with Minto making it clear what he and his colleagues intended doing.

“We will show them that we do not want them and that we intend to give them a hard time around the country,” Minto said.

By the end of the tour everyone involved - protestors, the Springboks, the thousands of police involved in ‘Operation Rugby’ and rugby fans - had certainly endured a “hard time”.

Norm Jones’ prediction that the police could handle what awaited “with their eyes closed” didn’t age well.

John Terris’ claim that “there will be blood – New Zealanders’ blood – spilt on every rugby field in the country” was much closer to the truth, as pro and anti tour arguments turned to violence on the streets and split the country in two.

56 Days of Mayhem

July 19: The Springboks fly into New Zealand, to be greeted by a large contingent of police and anti-protestors at Auckland International Airport.

July 22: Boks kick off the tour with a 24-6 win over Poverty Bay in Gisborne. Manager Johan Claassen gives what became his stock reply to questions about the protests: “We are here for the rugby”.

Protestors tar down the fence at Hamilton's Rugby Park ahead of a pitch invasion which forced the cancellation of the Waikato clash. Photo / NZME

July 25: Clash with Hamilton is cancelled after protestors invade pitch and pilot of a light plane threatens to crash into Rugby Park grandstand. Protestors later badly injured after being set upon by rugby supporters around the city.

July 27: The Government states the tour will go on, adding the army could be called in to help maintain law and order if needed.

July 29: The Springboks beat Taranaki 34-9. That night in Wellington scores of protestors are injured after violent clashes with police. It is later dubbed ‘The Battle of Molesworth Street’.

August 1: Heavy protests in Palmerston North on the day of the Springboks’ 31-19 win over Manawatu.

August 5: The tourists keep their unbeaten record intact by beating Wanganui 45-9.

Protests ramped up in size and in frequency around the country as the tour dragged on. Photo / NZME

August 8: First match of the South Island leg of the tour in Invercargill – a city which polls showed was pro-tour – where the Springboks beat Southland 22-6.

August 11: The Springboks wrap up preparations for the first test, beating Otago 17-3 in Dunedin.

August 13: The historic grandstand at Christchurch’s Rugby Park burns down in an arson attack after a Springbok training session.

August 15: Rugby fans clash with protestors outside Lancaster Park ahead of the first test. Some protestors make it briefly onto the field and the All Blacks beat the Springboks 14-9.

August 19: Scheduled clash against South Canterbury in Timaru is cancelled due to security fears.

August 22: The Springboks beat Nelson Bays 83-0 in Nelson, having spent time in the relative peace and quiet of the West Coast.

The Springboks in action the tense test series against the All Blacks. Photo / NZPA

August 25: Controversial 12-all draw with New Zealand Maori in Napier. Springbok Colin Beck later says he believed his late dropped goal to level the scores missed.

August 29: The Springboks level the test series in Wellington after beating the All

Blacks 24-12. The tourists had earlier spent the eve of the match sleeping in a function room at Athletic Park to avoid protestors.

September 2: Bay of Plenty go down narrowly to the Springboks in Rotorua, losing 29-24.

September 5: A big crowd in a fortified Eden Park watch the Springboks beat Auckland 39-12.

September 8: The Springboks win their final provincial clash 19-10 against Northland in Whangarei.

The Springboks prepare to run onto Eden Park ahead of the third test. Photo / NZME

September 12: On the fourth anniversary of anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko’s death, the All Blacks beat the Springboks 25-22. Scores of protestors and police are left badly injured after violent clashes around Eden Park. Flour bombs – including one which hits All Black Gary Knight – are dropped from a light plane buzzing the ground.

September 13: The Springboks fly out to America for three matches where more trouble awaits; including a match played behind closed doors, being guarded by heavily-armed FBI officers, and a pipe bomb being detonated outside a rugby union base.

This week (July 17-23) Neil Reid recaptures the incredible story of how the 1981 Springbok tour unfolded, including interviews with the key people involved. Click here to follow all his stories.

Springbok tour research: how does history interpret?

This weekend marks 40 years since the notorious flour-bomb incident at Eden Park during the 1981 Springbok tour.

Violence erupted outside the stadium grounds as protesters and police faced off, while others threw flour bombs and flares on the field to stop the game.

Although apartheid was a major factor behind the unrest, protesters were also actually critiquing wider New Zealand society, says sports historian Sebastian Potgieter .

- Download as Ogg

- Download as MP3

- Play Ogg in browser

- Play MP3 in browser

- Check out RNZ's collection of audio about the 1981 Springbok Tour

Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a South African who moved to Dunedin to conduct a PhD on the Springboks tour.

Back in 1981, the general public in South Africa wasn't too familiar with what was going on in New Zealand yet the Springbok tour of that year negatively affected the team's ability to play internationally, Dr Potgieter tells Kathryn Ryan.

"The South African government had a very strict information policy in place, which means that a lot of information, particularly that which was critical of the apartheid government, didn't actually make it through to the general public.

"In the wake of that tour, South African rugby came to be seen as somewhat of a symbolic liability and a lot of countries didn't want to play against South Africa.

"They felt that if the '81 tour is anything to go by, there was a likelihood of very extreme protests taking place in those countries which did host South Africa."

Dr Potgieter found it interesting to hear how vividly New Zealanders remembered the tour as it's not often spoken about in South Africa.

"We sort of know about incidents like the 'flour-bomb' test, but in general, South Africans don't know too much about this tour.

"It's still a matter which polarises opinions, so people have a lot to say about the tour, and have a lot to say about where they were, what they were doing during that tour."

Dr Sebastian Potgieter Photo: Supplied

It wasn't just apartheid that people were upset about in 1981 - protesters were also taking a stand against the deportation of Pacific Islanders and overstayers and the annexed Māori lands, Dr Potgieter says.

"We very selectively remember the past. It's impossible to remember the past in its entirety ... so certain parts of the past become elevated and contemporarily what we see in New Zealand.

"If you go back and look at some of the recollections of protesters who are writing shortly after the tour, we see that they say yes, apartheid was a problem, it was certainly what mobilised protests.

"But in the process of protesting a lot of people ... linked the protests to a lot of the racial discrimination that was happening in New Zealand at that time.

"It's more complex than simply saying this was an anti-apartheid protest and the anti-apartheid side of things is what's elevated at the moment, but it certainly doesn't define what those protests were about."

The demonstrations were also used as a platform to discuss the problematic aspects of rugby culture such as violence, gender stereotyping and alcoholism, he says.

People also need to remember that many New Zealanders supported the tour, Dr Potgieter says.

"Every single stadium during that entire tour was sold out and that there were large numbers of New Zealand television audience who tuned in to watch every game.

"We also see that a lot of New Zealand's far right and extremist groups actually have their biggest sort of phase of public acceptance or public profile when the question of South African tours cropped up in New Zealand.

"When those tours became put into jeopardy, these extremist groups or far right groups - whatever one wants to call them - received tremendous support in New Zealand."

Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a teaching fellow at the University Of Otago's school of physical education, sports and exercise sciences.

- Sebastian Potgieter

- anniversary

To embed this content on your own webpage, cut and paste the following:

<iframe src="https://www.rnz.co.nz/audio/remote-player?id=2018811821" width="100%" frameborder="0" height="62px"></iframe>

See terms of use .

Recent stories from Nine To Noon

- The week that was with Donna Brookbanks and Irene Pink

- Sports commentator Sam Ackerman

- Music reviewer Grant Smithies

- Around the motu: Kim Bowden covering Queenstown/Wanaka

- Book review: BBQ Economics by Liam Dann

Get the RNZ app

for easy access to all your favourite programmes

Subscribe to Nine To Noon

Podcast (MP3) Oggcast (Vorbis)

- Current exhibitions

- Coming soon

- For the kids

- History of the National Contemporary Art Award

- Collections

- Our stories

- Education programmes

- Planning your visit

- Education Booking Enquiry

- Contact the Education team

- Our history

- Quality Assurances and Testimonials

- Sustainability

- Our Community

- Working here

- Visitor Object Consideration Process

- Visitor Object Consideration Form

- Friends' events

- Friends of Waikato Museum Committee Members

- Membership Form

- Self-led groups

- Disability access

- Gallery Maps

- Spaces Available

- Venue Hire enquiry

Fight The Power

Springbok tour.

In mid-1981 an all-white South African ‘Springbok’ rugby squad made a controversial tour of New Zealand. The visit, hosted by the New Zealand Rugby Football Union (NZRFU) broke international cultural sanctions imposed against a racist South African regime. The tour attracted sharp criticism from the international community. The six week-long 1981 Springbok tour looms large in New Zealand public memory for the divisive battles it provoked, not just on rugby pitches but within families, schools, churches and workplaces.

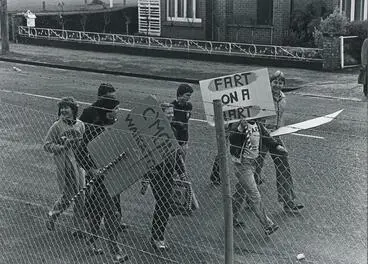

When the Springbok squad touched down at Hamilton Airport on Thursday 23 July they encountered an angry crowd of waiting demonstrators. Protests continued that night and the next at the Glenview Hotel, where the team was staying. The Springboks arrived early at Rugby Park on 25 July, the day of the match against the Waikato provincial team, in a bus covered in graffiti sprayed by protestors.

The campaign to disrupt the Hamilton match—Operation Everest—was well coordinated and involved several groups opposed to the tour. Eva Rickard and her daughter Angeline Greensil played prominent roles in the protest. The Scene at Rugby Park

Shortly before the marching to Rugby Park for the 2pm kick-off, Maaori activist Donna Awatere informed the crowd gathered in Garden Place that those involved in Operation Everest should move to the front of the march. Minutes after arriving at the park, approximately 300 protestors pushed through a perimeter fence to invade the centre of the pitch. They were confronted by pro-tour fans. The protester’s chants, ‘The Whole World is Watching!’, met the supporters’ refrain: ‘We Want Rugby!’ Police negotiated with protesters but were unable to move them. After approximately 50 minutes they began making arrests. At 3.09 pm the match was called off due to reports that a small-plane stolen from Taupo was heading to the game. The Waikato Times reported that ‘the announcement over the ground’s P.A. system provoked the crowd into uproar. Fighting between protestors and rugby supporters broke out amid howls of disapproval from the match crowd’. While attempting to leave the ground, protestors faced bottles and cans thrown by rugby fans. Violence continued throughout the night.

Want to learn more? Further reading

Trevor Richards, Dancing on Our Bones: New Zealand, South Africa, Rugby and Racism (Wellington: Bridget Williams, 1999).

Waikato Museum of Art and History, Let the Games(s) begin: Waikato v. South Africa, Rugby Park Hamilton , July 25, 1981.

Springbok tour protest at Hamilton, 25 July 1981

A DigitalNZ Story by Zokoroa

On 25 July 1981, anti-tour protesters led to the Springbok - Waikato rugby game being halted in Hamilton

Rugby , Sport , Springbok , Springboks , Hamilton , Anti-tour , Protests. Apartheid , Anti-apartheid , Racism , Anti-racism , HART , Politics

In 1981 the Springbok rugby team toured New Zealand which led to public protests. Those against the tour objected to South Africa's apartheid policies, whilst those supportive of the tour thought politics and sport shouldn't mix. The game against Waikato at Hamilton's Rugby Park on 25 July was called off when several hundred anti-tour demonstrators invaded the field. During the clashes between pro-tour and anti-tour supporters, over fifty arrests were made. The tour also led to debate about racism and the place of Māori in New Zealand.

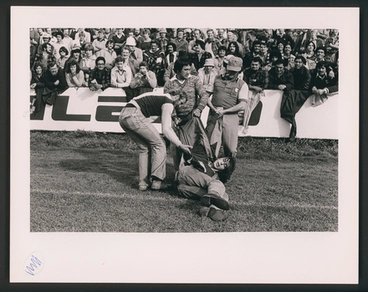

Two members of St John's College run onto Rugby Park, Hamilton, while two supporters of Springbok Rugby Tour try to stop them, 1981

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

"Confrontation on Centre Field" - 1981 Springbok Tour

Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato

Protesters in Hamilton during a demonstration against the 1981 Springbok tour - Photograph taken by Phil Reid

Alexander Turnbull Library

National protests

Protest badges - 1981 Springbok tour

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Stop the tour

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

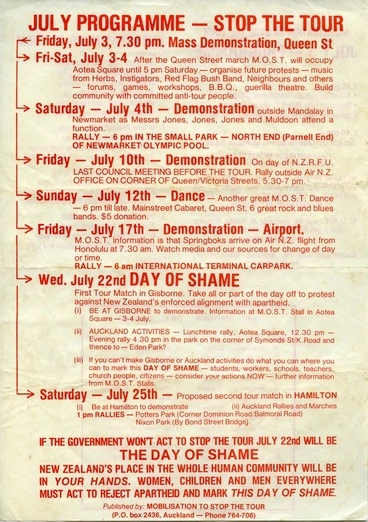

Springbok Tour protest programme

Poster was published by HART (Halt All Racist Tours) and handed out to anti-apartheid activists

Poster, 'The 50 Guilty People'

'No Tour' T-shirt

July petition to PM Robert Muldoon calling for the Springbok rugby team to be refused entry into NZ

Petition Cards to Robert Muldoon

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

'Don't mention the tour'

Waikato stadium, hamilton: 25 july 1981.

Hamilton's rugby wars - Roadside Stories

Demonstrators Handbook

Protestors lined up across road. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

Photograph - 1981 Springbok Tour

Members of St John's College before march to Rugby Park against Springbok Rugby Tour, Hamilton, 25 July 1981

![[Christian protesters sing in an outdoor shopping centre] Image: [Christian protesters sing in an outdoor shopping centre]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2Fcb169b4cfd2233f12df791c5af4ba06bc4470a1d%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[Christian protesters sing in an outdoor shopping centre]

Photograph – Springbok tour protest

Protesters hold anti-apartheid and anti-racism signs

Fence, Hamilton

Group of protestors middle of rugby field with spectators behind. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

Group of protestors including Geoff Chapple in middle of rugby field. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

![[Protesters occupy a rugby pitch] Image: [Protesters occupy a rugby pitch]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F12c490904f98340761e6a8bf5f035e791d6df33d%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[Protesters occupy a rugby pitch]

Policemen in riot helmets standing on Rugby Park, Hamilton, during the Springbok rugby tour - Photograph taken by Ian Mackley

"Rev. George Armstrong (St. Johns College, Auckland) pleading with Riot Squad" - 1981 Springbok Tour

Line of police confronting protestors. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

"Riot Squad on rugby field" - 1981 Springbok Tour

![[A police line and protesters face off on the rugby pitch at Rugby Park, Hamilton] Image: [A police line and protesters face off on the rugby pitch at Rugby Park, Hamilton]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F40cb0fdb2ef59bfbe1b9e1a93fd27d5ebf48b618%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[A police line and protesters face off on the rugby pitch at Rugby Park, Hamilton]

Police and tour protesters on Rugby Park, Hamilton - Photograph taken by Phil Reid

Baton used by two special police squads formed as security escorts for Springboks

PR 24 baton

Protestors and police officers at Rugby Park, Hamilton - Photograph taken by Phil Reid

Hamilton, 25 July

Police confronting protestors on rugby field. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

Police separating demonstrators & rugby Fans Hamilton.

Police struggle with demonstrators, Hamilton - Photograph taken by Ian Mackley

Rugby supporters hand a demonstrator off the Field, Hamilton.

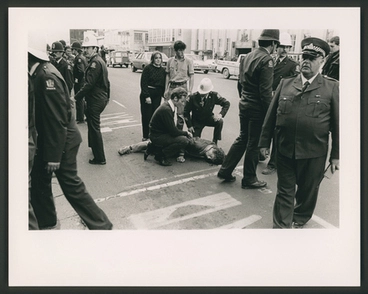

A demonstrator lies bloody unconscious in Victoria St, Hamilton.

![[Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton] Image: [Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F850aa51c4f15738b036acfa8730c91ebbc69b21d%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton]

![[Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton] Image: [Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F92d515aa64923b96854a7fdfe70fcdde07a4a9d3%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

This calendar was produced in 1982 to raise legal funds for protesters who had been arrested during Springbok tour

Days of Rage calendar

Reaction in south africa.

The Waikato game was the first being televised live back to South Africa, so viewers there saw the NZ opposition to the tour and apartheid.

Try Revolution

NZ On Screen

Bromhead, Peter, 1933- :'Right Jan...you on the vickers..and the other nineteen pick up the bodies...' Auckland Star, 28 July 1981.

1981 springbok captain recalls impact of pitch invasion.

Radio New Zealand

Personal accounts

After the tour, English Department of University of Canterbury placed adverts to gather people's comments & experiences

Springbok Tour Archive [Pro]: Hamilton group on democracy versus communism.

University of Canterbury Library

John Minto, national organiser of Halt All Racist Tours (HART), looks back on the 1981 Springbok tour

John Minto - 1981 Springbok tour

Blazey discussing the 1981 springbok tour, stories told about violence : hamilton during the 1981 springbok tour / by nikita prinsloo.

National Library of New Zealand

Springbok Tour Archive [Anti]: Hamilton woman's note on experience and feelings during the tour.

Springbok tour archive [anti]: coromandells housewife's account of trip to hamilton and repercussions., springbok tour archive [pro]: hamilton person, 60. nz freedoms, protest activity, anti-authority elements., springbok tour archive [anti]: christchurch middle-aged man discussing maoris and racism., springbok tour archive [pro]: a northland woman's views on communism, professional 'stirring', hamilton match, violent protest etc., video / audio.

1981 - A Country at War

Waikato game stopped, 1981

The game that never was

Film: game cancelled in hamilton, 1981 springbok tour, hamilton's rugby wars - roadside stories, report on protests at rugby park.

Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision

Anti-Springbok-tour veterans on the power of HART

Books / articles.

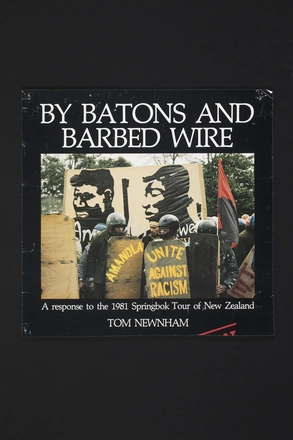

By batons and barbed wire

Roadside stories: hamilton's rugby wars, anti-springbok protesters block hamilton match.

(This DigitalNZ Story was compiled in 2020)

New Zealanders protest against Springbok rugby tour, 1981

Time period, location description, methods in 1st segment, methods in 2nd segment, methods in 3rd segment, methods in 4th segment, methods in 5th segment, methods in 6th segment, additional methods (timing unknown), segment length, external allies, involvement of social elites, nonviolent responses of opponent, campaigner violence, repressive violence, classification, group characterization, groups in 1st segment, success in achieving specific demands/goals, total points, notes on outcomes, database narrative.

Halt All Racist Tours (HART) was organized in New Zealand in 1969 to protest rugby tours to and from South Africa. Their first protest, in 1970, was intended to prevent the All Blacks, New Zealand’s flagship rugby squad, from playing in South Africa, unless the Apartheid regime would accept a mixed-race team. South Africa relented, and an integrated All Black team toured the country.

Two years later, the Springboks arranged a tour of New Zealand. HART held intensive planning meetings, and, after laying out their nonviolent protest strategies to the New Zealand security director, he was forced to recommend to the government that the Springboks not be allowed in the country. Prime Minister Kirk, though he had promised not to interfere with the tour during his election campaign, canceled the Springbok’s visit, citing what he predicted would be the “greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known.”

HART remained active in the anti-apartheid community, continuing to protest the Springboks, and helping to organize a boycott of the 1976 Montreal Olympics. The International Olympic Committee had not banned New Zealand after the All Blacks had toured South Africa, and many African countries saw this failure as a tacit endorsement of Apartheid. In 1980, New Zealand again attempted to bring the Springboks to New Zealand.

The Springboks arrived on July 19, 1981. Though they were officially welcomed by the New Zealand government, there was a sense of dread and anticipation that surrounded their arrival – perhaps, some thought, the 1981 tour should have been cancelled like the tour in 1972 was. The government officials could not anticipate, however, that the country was about to fall into “near-civil war.” In response to HART, pro-rugby groups like Stop Politics in Rugby (SPIR) organized in an effort to help the Springbok’s tour succeed. Both sides tended to be easily identified by armbands that made their affiliation clear. In particular, HART activists wore their armbands for the entire length of the tour, subjecting themselves to constant ridicule and the threat of violence, despite their commitment to nonviolent protest only.

The Springboks played their first game on July 22 in Gisborne. An anti-Springbok rally took place that day, near the rugby pitch. When the campaigners arrived at the arena, they were confronted by pro-rugby demonstrators. Because Gisborne, like most cities in New Zealand, was close-knit, demonstrators on both sides knew each other, and were not afraid to call each other out for supporting the wrong side, whichever they believed that was. The pro-rugby demonstrators did not restrict themselves to words, even throwing stones at the other side. The anti-Springbok protesters could not stop the match that day. Though they were able to break through the perimeter fence, and engage the pro-tour demonstrators face to face, they were prevented from occupying the field. Though both sides reported that they were uneasy with the clashes between fellow New Zealanders, neither side was easily swayed.

Three days later, the Springboks were scheduled to play in Hamilton. Anti-Springbok planners had circulated a strategy that would hopefully allow them to tear down the fence, invade the field, and disrupt the match. Protesters had also secured more than 200 official tickets to the match, to make sure that their presence was felt, even in the event that they could not storm the pitch. Despite the presence of more than 500 police officers and a sizable pro-rugby contingent, the anti-Springbok march would prove unstoppable. 5000 anti-Springbok protesters descended upon the Hamilton pitch, and more than 300 made it onto the field, forcing a match cancellation. Protesters chanted that the whole world was watching. Many of the demonstrators were arrested, and those on the pitch endured a constant bombardment of bottles and other objects from rugby fans in the stands. This entire situation was captured on live TV and shown around the world.

With tensions in New Zealand reaching astronomical proportions, the Springboks were next scheduled to play four days later, on July 29. The anti-Springbok protesters were largely absent from the match, but had instead planned a march on the South African consulate in Wellington, New Zealand. Despite police declaring that a march was not permitted, the protesters marched right up to the police line on Molesworth Street. The police began to stop the marchers with their batons, violently forcing them away from the consulate building. The marchers, stunned and bloodied, turned towards the police station, chanting “Shame, shame, shame.” When they arrived, the accosted marchers pressed assault charges on the police that had attacked them. Though the charges were dismissed, the policing of the tour protests had taken a turn for the worse. From this point on, protesters were careful to carry shields and wear crash helmets in order to protect themselves from attacks.

Protests would continue for the entire length of the Springbok’s stay in New Zealand. Only one more match was cancelled, in Timaru. However, there were a few more notable encounters. In Christchurch, on August 15, protesters failed to occupy the pitch in time for the game to be cancelled. The police cordon around the arena held, and several observers believe that the police saved the lives of many protesters. The attacks of rugby supporters were growing more and more violent, The Christchurch incident was characterized by flying blocks of cement and full beer bottles. Had the anti-Bok protesters succeeded in reaching the field, the attacks would certainly have been even more dangerous.

The final match of the tour was in Auckland on September 12. Not only was the match important as a final chance for protesters to demonstrate their opposition to the Springboks, it was the deciding third meeting between the Springboks and the All Blacks. Doug Rollerson of the 1981 All Blacks recalled that it seemed very important for the All Blacks to win the match, to show that a mixed team was superior to the segregated Springbok side. When the All Blacks won, the sense of victory in New Zealand was similar to the US victory over the Soviet Union in 1980 – the triumph of righteousness over the evil empire. However, for most observers around the world, the off-field events were far more important. Though the protesters were generally non-violent, there were many others that joined in the marches – HART characterized them as opportunists that simply wanted to fight with police. Though eruptions of violence had taken place throughout the campaign, they were largely viewed by the protesters as third-party actions, and HART consistently distanced themselves from violent attacks. More memorably, Max Jones and Grant Cole commandeered a prop plane, and proceeded to drop flares and flour bombs on the pitch during play in an attempt to stop the game. Though the game continued, the actions of the protesters were again the primary news story in New Zealand and throughout the world.

Though the anti-Springbok protests were largely unsuccessful in that the vast majority of the planned contests took place, they were able to raise an incredible amount of awareness for the anti-Apartheid movement. Nelson Mandela recalled that when the game in Hamilton was cancelled, it was “as if the sun had come out.” HART would continue protesting until the fall of the Apartheid regime.

Influenced and influenced by anti-Springbok protests in other countries like Australia, Britain (see "Australians campaign against South African rugby tour in protest of apartheid, 1971" and "British Citizens Protest South African Sports Tours (Stop the Seventy Tour), 1969-1970") (1,2).

This campaign was also influenced by the New Zealand Waterfront Strike (1951) (1).

Additional Notes

Name of researcher, and date dd/mm/yyyy.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

In July 1969 HART (Halt All Racist Tours) was founded by University of Auckland students with the specific aim of opposing sporting contact with South Africa. With a Springbok tour to New Zealand scheduled for 1973, the issue was to become increasingly politicised. Kirk and the Springbok issue. In the run-up to the 1972 election, Norman Kirk ...

Fifty years ago a rugby tour of New Zealand was scheduled. After loud and often rowdy protest against it, the tour was called off. Trevor Richards remembers the cancelled Springbok Tour of 1973 ...

During the 1972 election campaign, Kirk (then leader of the Opposition) had promised not to interfere with the tour. After Labour won office, he attempted unsuccessfully to persuade the NZRFU to withdraw its invitation to the Springboks. At the same time he negotiated with anti-tour activists and groups. While he was aware of the likely fallout ...

Today, few know anything much about it. It is the forgotten campaign. The tours of 1981 and to a lesser extent, 1976, are better recalled, largely because their dreadful outcomes were hard to ignore. The events of 1973 go mostly unnoticed, buried by the dramas of 1976 and 1981. Yet to this activist/student of history — and there's a ...

Fifty years ago today, Labour Prime Minister Norman Kirk stopped the 1973 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand. Frank Corner, Secretary of Foreign Affairs during Kirk's Prime Ministership, ...

The last apartheid-era Springbok rugby team landed in New Zealand 40 years ago, on July 19 1981. In the 500 days leading up to the South African team's arrival the anti-tour movement predicted ...

Cancelation of 1973 tour. A key cause which resulted in the 1981 Springbok tour protests was the cancellation of the 1973 tour. Throughout the Springbok tours of Britain and Australia in 1970 and 1971, there were a number of strong and somewhat violent protests, culminating in a sense of unrest in both South Africa and their host countries.

Forty-five years ago this week, debate was raging in New Zealand over something that never happened - the 1973 Springbok tour of New Zealand, which had just been cancelled by the Labour government of Prime Minister Norman Kirk.

Fifty years ago this month, Labour prime minister Norman Kirk announced the cancellation of the scheduled 1973 Springbok tour of New Zealand. Halt All Racist Tours movement (Hart) leader Trevor Richards assesses the significance of the tour's cancellation ... And the cancelled 1973 tour? Today, few know anything much about it. It is the ...

1973 springbok tour to nz cancelled Kirk argued that the country should not be put through the social turmoil that was likely to result if the tour proceeded. Plus, he didn't want to risk a boycott the 1974 Commonwealth Games to be hosted at QEII in Christchurch.

e success of the Springbok tour postponement decision ena - bled Kirk to make a ying start to his global diplomacy. Bassett s realisation came following an urgent Caucus meet - ing called on the evening of 15 February 1973, the new Parlia-ment having formally opened earlier that day. e forthcoming Springbok tour was the Caucus sole topic.

From Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage: Keeping sport and politics separate was becoming increasingly difficult. In July 1969 HART (Halt All Racist Tours) was founded by University of Auckland students with the specific aim of opposing sporting contact with South Africa.

1981 Springbok tour. For 56 days in July, August and September 1981, New Zealanders were divided against each other in the largest civil disturbance seen since the 1951 waterfront dispute. The cause of this was the visit of the South African rugby team - the Springboks. Read the full article.

Check out RNZ's collection of audio about the 1981 Springbok Tour; Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a South African who moved to Dunedin to conduct a PhD on the Springboks tour. Back in 1981, the general public in South Africa wasn't too familiar with what was going on in New Zealand yet the Springbok tour of that year negatively affected the team's ability to play internationally, Dr Potgieter tells ...

The Springbok Tour. The springbok tour of the 1980's was the largest civil disturbance New Zealand had seen in thirty years. The whole of New Zealand was divided over the tour, this division of the country lasted over fifty days. The Springbok tour was a real factor in the way New Zealand grew as a county. The outcomes that arose from the ...

Read a story about the 1981 Springboks rugby tour. The 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand caused social ruptures within communities and families across the country. With the National government backing the tour, protests against apartheid sport turned into confrontations with both police and pro-tour rugby fans — on marches and at matches.

Police officers guarding a barbed wire perimeter around Eden Park near Kingsland railway station. The 1981 South African rugby tour (known in New Zealand as the Springbok Tour, and in South Africa as the Rebel Tour) polarised opinions and inspired widespread protests across New Zealand. The controversy also extended to the United States, where ...

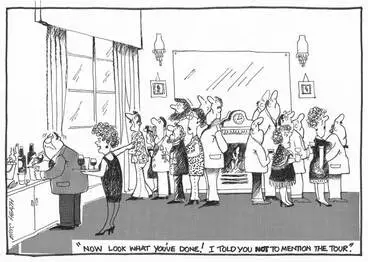

Crumpled on the floor is a newspaper announcing the cancellation of the 1973 Springbok Tour by the Prime Minister. The man's wife is explaining to another woman that the photograph turned to the wall is that of Norman Kirk. Extended Title - P.M. Cancels Springbok Tour Quantity: 1 original cartoon(s).