Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Find in topic

CALCULATORS

Related topics.

INTRODUCTION

The three main components of prenatal care are: risk assessment, health promotion and education, and therapeutic intervention [ 1 ]. High-quality prenatal care can prevent or lead to timely recognition and treatment of maternal and fetal complications. Complications of pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in females of reproductive age globally [ 2 ].

This topic will discuss the initial prenatal assessment (which may require more than one visit) in the United States. Most of these issues are common to pregnancies worldwide. Preconception care, ongoing prenatal care after the initial prenatal assessment, and issues related to patient counseling are reviewed separately.

● (See "The preconception office visit" .)

● (See "Prenatal care: Second and third trimesters" .)

● (See "Prenatal care: Patient education, health promotion, and safety of commonly used drugs" .)

Pregnancy Changes and The First Prenatal Visit

Pregnancy is a transformative and exciting journey that brings profound physical and emotional changes for expectant mothers. As nursing professionals, understanding and addressing these changes is essential in providing comprehensive care during pregnancy. The first prenatal visit holds immense significance as it sets the foundation for a successful pregnancy journey, ensuring optimal maternal and fetal well-being through early detection, education, and tailored care plans.

This article aims to serve as a comprehensive nursing guide, focusing on the common pregnancy changes experienced by women and the critical aspects of the first prenatal visit. This serves as a valuable resource, equipping nursing professionals with the knowledge and skills necessary to provide comprehensive care, support, and education to women embarking on the beautiful journey of pregnancy.

Table of Contents

Presumptive signs, probable signs, positive signs, reproductive system changes, breast changes, integumentary system, respiratory system, cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal system, urinary system, skeletal system, endocrine system, mood swings, changes in sexual desire, introversion/extroversion, social changes, cultural changes, family changes, individual changes, first trimester: accepting the pregnancy, second trimester: accepting the baby, third trimester: preparing for the baby, breast tenderness, palmar erythema, constipation, nausea, vomiting, pyrosis, muscle cramps, hypotension, varicosities, hemorrhoids, heart palpitations, frequent urination, ankle edema, braxton hicks contraction, recommended weight gain, energy needs, protein needs, vitamin needs, mineral needs, fluid needs, fiber needs, healthy signs of good nutrition, health history, demographic data, chief concern, history of past illnesses, history of family illnesses, social profile, gynecologic history, obstetric history, systemic assessment.

- Papanicolaou Smear (Pap smear)

Blood Studies

Glucose tolerance test, ultrasonography, preconception classes, expectant parenting classes, sibling education classes, breastfeeding classes, preparation for childbirth classes, the bradley method, the dick-read method, the lamaze method, the appropriate setting, the birth attendant and support person, hospital birth, alternative birthing centers, physiological changes in pregnancy.

A woman certainly undergoes a lot of changes during pregnancy. Some gain changes permanently, others have changes that are very subtle. These changes, however, are welcomed by mothers with open arms because they are signs that a new life is being formed inside of her.

The Diagnosis of Pregnancy

Before a pregnancy is confirmed, the woman might see small and big changes in her body that could help in determining if she is already pregnant.

Presumptive signs are signs that are least indicative of a pregnancy. These changes can only be felt by the woman but cannot be documented by the healthcare provider.

- Breast changes (swollen), nausea and vomiting , amenorrhea, frequent urination , fatigue , uterine enlargement, quickening , linea nigra, melasma, and striae gravidarum are the presumptive signs of pregnancy.

- However, these signs may also denote other conditions that the body is undergoing.

Probable signs of pregnancy are objective and can be seen primarily by the healthcare provider. These can be taken through laboratory tests and home pregnancy tests by detect the presence of human chorionic gonadotropin in the blood or in the urine .

- Chadwick’s sign or a change in the color of the vagina from pink to violet is a probable sign of pregnancy.

- Goodell’s sign is a probable sign that depicts a softening of the cervix.

- Hegar’s sign is the softening of the lower uterine segment.

- Ballottement is described as the rise of the fetus felt through the abdominal wall when the uterine segment is tapped on a bimanual examination.

- An evidence of a gestational sac found during ultrasound is another probable sign.

- Braxton-Hicks contractions are periodic uterine tightening and contractions.

- The fetal outline can also be now palpated by the examiner through the abdomen.

There are only three positive signs of pregnancy that are documented by the health care providers.

- Evidence of a fetal outline on ultrasound.

- With the use of a Doppler, an audible fetal heart rate is another positive sign.

- The last is fetal movement felt by the healthcare provider.

The system that will greatly feel the changes is the reproductive system. It includes the ovaries, uterus, and vagina.

- On the first trimester in the ovaries, the corpus luteum starts to become active. By the second trimester, it begins to fade until the third trimester where it has already disappeared.

- The uterus increases in growth starting from the first trimester. On the second trimester, the placenta is forming estrogen and progesterone .

- The vagina undergoes changes during the first trimester wherein a whitish discharge is present. From the second until the third trimester, the whitish discharge increases in amount.

- Amenorrhea also occurs, or the absence of menstruation .

- The cervix undergoes a more vascular and edematous appearance owing to the increased level of estrogen.

- Breast changes start from the first trimester as the woman feels tenderness and fullness of her breasts.

- As the pregnancy progresses, the breast size increases a size or two, as the mammary alveoli and fat deposits increase in size.

- The areola of the nipples become darker and its diameter increases.

- The vascularity of the breast also increases, as evidenced by the prominent blue veins over the surface.

- The Montgomery’s tubercles or the sebaceous glands of the areola protrudes and enlarges.

Systemic Changes

After the changes that occurred mainly in the reproductive system of a pregnant woman, systemic changes will also start to occur in different body systems.

- The stretching of the abdomen causes rupture of the small segments of the connective layer of the skin.

- Striae gravidarum or pinkish to reddish marks on the sides of the abdominal wall are the result of the rupture.

- Linea nigra is a narrow, brown line that runs from the symphysis pubis to the umbilicus and separates the abdomen into right and left hemispheres.

- Melasma or chloasma (mask of pregnancy) refers to the darkened areas on the cheeks or the nose that may appear during pregnancy.

- Telangiectasis is red, branching spots that can be seen on the thighs. It is also called as vascular spiders.

- Palmar erythema also occurs because of the increase in the estrogen level of the pregnant woman.

- A pregnant woman usually experiences stuffiness or marked congestion because of the increasing estrogen levels.

- Shortness of breath is also a common discomfort of pregnancy as the pregnant uterus pushes the diaphragm upward.

- The total oxygen consumption of a pregnant woman increases by 20%.

- The blood pressure of the pregnant woman decreases in the second trimester and then returns to its prepregnancy level on the third trimester.

- The cardiac output increases 25% to 50%.

- Plasma volume also increases up to 3600 mL, marking the condition called pseudoanemia early in the pregnancy.

- Heart rate also increases to 80 to 90 beats per minute.

- The blood volume increases up to 5,250 mL during pregnancy.

- Nausea and vomiting is one of the first signs of pregnancy that a woman feels.

- Slower intestinal peristalsis occurs during the second trimester of the pregnancy which causes heartburn, flatulence, and constipation .

- Hemorrhoids also occur from the increased pressure of the uterus on the veins in the lower extremities.

- The total body water of a pregnant woman increases up to 7.5 L for a more effective placental exchange.

- Even when the woman has an increased urine output, her potassium levels are still adequate due to progesterone, which is potassium -sparing.

- The bladder capacity increases to accommodate 1,000 mL of urine during pregnancy.

- On the first trimester, the frequency of urination already increases. By the last two weeks of pregnancy it reaches up to 10 to 12 times per day.

- By the 32 nd week of pregnancy, the symphysis pubis widens for 3 to 4 mm.

- The center of gravity of a pregnant woman changes, and to make up for it she tends to stand straighter and taller than usual and with the abdomen forward and the shoulders thrown back, the ‘pride of pregnancy’ or commonly ‘lordosis’ occurs.

- A slight enlargement in the thyroid and parathyroid gland increases the basal metabolic rate of a pregnant woman and for better consumption of calcium and vitamin D.

- Thyroid hormone production increases.

- The insulin produced from the pancreas decreases early in the pregnancy, thereby increasing glucose available for the fetus.

- Increase in insulin occurs in the first trimester because estrogen, progesterone and HPL have insulin antagonistic properties.

- FSH and LH decreases causing anovulation .

- As the breasts are prepared for lactation, prolactin increases in production.

- The increase in melanocyte-stimulating hormones causes increase in skin pigment.

- The human growth hormone increase to aid the fetus in growing.

- Estrogen and progesterone aids in uterine and breast enlargement.

- Human placental lactogen increases glucose levels to supplement the growing fetus.

- Relaxin increases to soften the cervix and collagen of joints.

The changes in the physiologic status of a pregnant woman are just one of the many phases of changes that occur during pregnancy. Most of these are normal, but when the pregnant woman experiences an excessive manifestation of these signs, it would be best to consult your healthcare provider.

Psychological Changes in Pregnancy

The various changes that a woman undergoes during pregnancy entirely sweep the entirety of the human body. Almost every aspect is altered, hormones get together to create a whole new modifications in the mind, the body, and the emotions. Psychological aspects would also be given a new perspective as it also alters together with the rest of the woman’s body.

How a Woman Responds to Pregnancy

Mood swings, grief , changes in sexual desires, and stress are only some of the psychological changes that a pregnant woman experiences. The couple might misinterpret these changes, so health education must be integrated in the care of the pregnant woman.

- Grief may arise from the realization that one’s roles would be changed permanently.

- A pregnant woman would be weaned off her role as a dependent daughter, or as a happy-go-lucky girl, or a friend who is always available.

- Even the partner would have to leave the roles or the life he has been accustomed to as a man without a child to support.

- Also known as emotional lability, this psychological reaction can be caused by two factors: hormonal changes or narcissism.

- The comments that she had brushed off in her nonpregnant state can now touch a nerve or hurt her.

- Crying is a common manifestation of mood swings, during and even after the pregnancy.

- Women who are on the first trimester of pregnancy experience a decrease in libido mainly because of breast tenderness, nausea, and fatigue .

- On the second trimester, sexual libido may rise because of increased blood flow to the pelvic area that supplies the placenta.

- The third trimester might bring an increase or decrease in sexual libido due to an increase in the abdominal size or difficulty in finding a comfortable position.

- Estrogen increase may also affect sexual libido as it may bring a loss of desire.

- The couple must be informed that these changes are normal to avoid misunderstanding the woman’s attitude.

- Pregnancy is a major change in roles that could cause stress.

- The stress that a pregnant woman feels might affect her ability to decide.

- The discomforts that she may feel could also add up to the stress she is experiencing.

- Assess whether the woman is in an abusive relationship as it may contribute further to the stress.

- Introversion refers to someone who focuses entirely on her own body and a common manifestation during pregnancy.

- Some pregnant women also manifest extroversion, or acting more active, healthier and more outgoing than before their pregnancy.

- Extroversion commonly happens to women who had a hard time conceiving and finally hit jackpot.

- In the past, a pregnant woman is isolated from her family starting from visiting for prenatal consultation until the day of birth.

- She is isolated from her family and the baby a week after birth.

- Today, having a support system for pregnant women is highly encouraged, like bringing along someone to accompany her during prenatal visits and allowing the husband to be with the wife during birth if he chooses to.

- Opinions on teenage pregnancy, late pregnancies, and having the same sex parents are now widely accepted compared to being taboos in the past.

- A pregnant woman’s culture and beliefs may also greatly affect the course of her pregnancy.

- Assess if the woman and her partner have particular beliefs that might affect the way the take care of the pregnancy so you can integrate them in your plan of care.

- Despite the modern ages, there are still groups who firmly believe in their culture’s explanations about birth complications and the health care providers must respect this.

- Myths that surround the pregnancy should always be respected, but the couple should be educated properly regarding what could be dangerous for the fetus’ health.

- The environment where the woman grew influences the way she would perceive her pregnancy.

- Family culture and beliefs also affect a woman’s perception of pregnancy.

- If she is loved as a child, she would have an easy time accepting her pregnancy compared to women who were neglected by her family during childhood.

- A woman who has been told of disturbing stories about giving birth and pregnancy would view her own in a negative light, while those who grew with beautiful birth stories would more likely be excited for their pregnancy.

- A positive attitude would only result from a positive outcome and influence from the woman’s own family.

- Becoming a new mother is never an easy transition. The woman must first be able to cope with stress effectively, as this is a major concern during pregnancy.

- She needs to have the ability to adapt effectively to any situation, especially if the pregnancy is her first because there might be a lot of new situations that would arise.

- Her ability to cope with a major change and manage her temper would be put to a test during motherhood.

- The woman’s relationship with her partner also affects her ability to accept her pregnancy easily.

- If she feels secure with her relationship with the father of her child, she would have an easier time accepting her pregnancy as opposed to an unstable relationship where she feels insecure and may doubt the decision of keeping the pregnancy.

- A woman who feels that the pregnancy may rob her of her looks, her freedom, a promotion, or her youth would need to have a strong support system so she could express her feelings and unburden her chest.

- The father’s acceptance of the pregnancy also influences the woman’s ability to accept the marriage.

- Utmost support from her husband would be very meaningful for the woman especially during birth.

The Psychological Tasks of Pregnancy

Both the woman and her husband walk through a tangle of emotions during pregnancy. Accepting that a new life would be born out of your blood is not as easy as others may think. There are several stages that both should undergo, the psychological way.

- The shock of learning about a new pregnancy is sometimes too heavy for a couple, so it is just proper for the both of them to spend some time recovering from this major life-altering situation and avoid overwhelming themselves at first.

- One of the most common reactions of a couple who would be having a baby for the first time is ambivalence, or feeling both pleased and unhappy about the pregnancy.

- The woman and her partner will start to merge into the role of novice parents as second trimester closes in.

- Emotions such as narcissism and introversion are commonly present at this stage.

- Role playing and increased dreaming are activities that help the couple embrace their roles as parents.

- At this stage, the woman and her partner must start to concentrate on what it will feel like to be parents.

- The couple starts to grow impatient as birth nears.

- Preparations for the baby, both small and big, takes place during this stage.

- The baby’s clothing and sleeping arrangements are set and the couple is excited for his arrival.

The transition of a woman from the start until the end of the pregnancy is a big turning point for her and the people who surround her. Every single one of them must be prepared physically, mentally and emotionally because pregnancy is also considered a crisis in life; something that could turn your world upside down.

Discomforts of Pregnancy

Pregnancy ultimately builds up a woman. It is the pinnacle of life wherein women become more than just women; they become mothers. The journey of pregnancy is also a tough one but is meaningful and wonderful. The discomforts a woman would undergo are just bumps along the road of fulfillment once she has delivered her child.

Discomforts during the First Trimester

There are a number of discomforts that can be felt during the first trimester. This is the time when the body is just starting to adjust to the pregnancy, and hormones are still in chaos. The woman must be educated on how to ease these discomforts to help her adjust slowly.

Breast tenderness is one of the first symptoms that the woman would notice in early pregnancy. The tenderness may vary between women; some hardly notice the sensation at all.

- Advise to wear a bra with a wide shoulder strap. The support it gives helps ease the tenderness.

- Dress warmly and avoid cold. She should also dress warmly as exposure to cold increases the tenderness.

- Get examined. Women who experience intense pain should have to examine the presence of nipple fissures or breast abscess to rule out these conditions.

Palmar erythema is the constant itching and redness of the palms but is not considered an allergy . Increased estrogen levels possibly cause the pruritus.

- No it’s not an allergy . Educate the woman that she has not developed an allergy, and this is normal during pregnancy.

- Calamine lotion to the rescue. To soothe the itchiness, calamine lotion can be applied.

- Disappears naturally. Palmar erythema would naturally disappear once the body has adjusted to the increased estrogen levels.

Constipation is caused by slow peristalsis due to the pressure from the growing uterus.

- Increase fiber in the diet. Encourage the woman to move her bowels regularly and increase the fiber in her diet.

- Drink water. Advise her to drink at least 8 to 10 glasses of water every day.

- Iron supplements. Educate her that iron supplements can cause constipation but need not be stopped because it helps build up fetal iron stores.

- Don’t use mineral oil. The use of mineral oil to relieve constipation is not advisable because it absorbs the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, K, and E.

- Don’t use enemas. Enemas are also prohibited as it may initiate labor .

- So as OTC laxatives. Over-the-counter laxatives are also contraindicated unless prescribed.

- Avoid gas-forming foods. Advise the woman to avoid gas-forming food to prevent excessive flatulence.

Nausea and vomiting are also one of the earliest symptoms of pregnancy. Pyrosis or heartburn typically occurs when the woman ate a large meal.

- Small frequent feedings. Advise the woman to take small, frequent meals and avoid greasy foods.

- Upright position after. Encourage her to keep in an upright position after meals to avoid reflux.

Pregnant women experience fatigue mostly in early pregnancy because of increased metabolic requirements .

- Rest and sleep . Advise her to increase the amount of rest and sleep and to continue with her normal nutrition intake.

- Take short breaks. For women who still work, advise her to take short breaks, especially if her work involves being up and about the whole day.

Muscle cramps are caused by decreased serum calcium levels, increased phosphorus levels, or interference in the circulation.

- Lie down. Advise the woman that when this happens, she should lie on her back and extend the affected leg while she keeps her knee straight and dorsiflexes the foot.

- Magnesium citrate or aluminum hydroxide gel. Magnesium citrate or aluminum hydroxide gel is prescribed to women who have frequent and unrelieved muscle cramps.

- Raise those feet. The woman should elevate her lower extremities frequently to promote circulation.

When the woman lies on her back and the uterus presses upon the vena cava , supine hypotension might occur, impairing blood return to the heart.

- Sleep sideways. Advise woman to rest or sleep on her side, not on her back.

- Rise slowly. Encourage her to rise slowly and dangle feet over the bed for a few minutes; avoid standing for extended periods.

Varicosities are tortuous veins caused by the pressure of the uterus to veins at the lower extremities.

- Raise legs. Advise the woman to rest in Sim’s position or on the back with the legs raised against the wall.

- Don’t cross legs. Discourage sitting with legs crossed or knees bent and the use of constrictive knee-high hose or garters.

- Support stockings do wonders. The use of elastic support stockings is advised to relieve varicosities.

- Exercise and walk. Exercise is also effective through taking walk breaks from chores or from standing or sitting for too long.

- Vitamin C helps. Vitamin C is also recommended to reduce varicosities for the formation of blood vessel collagen and endothelium.

Hemorrhoids are varicosities of the rectal veins that occur because of the pressure of the veins from the weight of the uterus.

- Evacuate daily. Advise the woman to evacuate her bowels daily and resting on a Sim’s position.

- Knee-chest position . Encourage the woman to assume a knee-chest position for 10-15 minutes at the end of the day to relieve the pressure on the rectal veins.

- Stool softener. If the woman already has hemorrhoids , a stool softener would be recommended.

- Relieving hemorrhoids. The pain of hemorrhoids could also be relieved by applying witch hazel or cold compresses to external hemorrhoids.

Heart palpitations may occur when upon sudden movement the woman experiences bounding palpitation of the heart. This is mainly due to circulatory adjustments necessary to accommodate her increased blood supply during pregnancy.

- Slow and steady. Advise the woman to move in slow, gradual movements to prevent heart palpitations.

The pressure of the uterus on the bladder causes frequent urination . Frequency occurs early in the pregnancy and late in the pregnancy.

- No fluid restriction. Advise the woman not to restrict her fluids to diminish the frequency of urination, instead; caffeine intake should be diminished.

- Offer assurance. Assure the woman that voiding frequently is a normal occurrence during pregnancy.

- Kegel’s exercises. Kegel’s exercise also helps to reduce the incident of stress incontinence and helps regain the strength of urinary control and strengthens perineal muscles for birth.

Discomforts during the Second and Third Trimester

The last trimesters of pregnancy also have their set of discomforts that you have to differentiate from complications that might arise.

Lumbar lordosis develops as pregnancy progresses to maintain the balance.

- Low heels. Advise the woman to wear shoes with low to moderate heels to reduce the amount of spinal curvature necessary to maintain an upright position.

- Warm compress. Backache can be relieved by applying local heat on the area.

- Body mechanics. Advise the woman to squat rather than bend over to pick up objects.

- Close to center of gravity. Advise the woman to lift objects by holding them close to the body.

Dyspnea results from the pressure of the expanding uterus on the diaphragm. Dyspnea is prominent especially when the woman lies flat on the bed at night.

- Proper sleeping position. Encourage the woman to sleep with her head and chest elevated.

- Limit activities. Advise her to limit her activities during the day to prevent exertional dyspnea .

Late in pregnancy, some women experience swelling of the ankles and feet. The edema is caused by general fluid retention and reduced blood circulation in the lower extremities.

- Watch out for proteinuria or eclampsia . Assess if the woman has hypertension or proteinuria to rule out eclampsia.

- Sleep on the left side. Advise the woman to lie on her left side when resting or sleeping.

- Sit. Encourage her to sit half an hour in the afternoon and in the evening with legs elevated and to avoid constrictive clothing.

From the 8 th to the 12 th week of pregnancy, the uterus periodically contracts and relaxes, and this is termed as Braxton Hicks contraction.

- Give assurance. Assure the woman that these are not signs of early labor , but they can inform their healthcare provider about them.

A pregnant woman would always want reassurance that her pregnancy is healthy. These discomforts may alarm her, especially if she knows little about the physiology of pregnancy, so it is the role of healthcare providers to guide her and be there for her whenever she needs them throughout the pregnancy.

Nutritional Health During Pregnancy

One of the most important aspects in pregnancy is the woman’s nutritional status . Despite the discomfort she may feel towards eating early in pregnancy, she should never take her nutrition for granted because of the life that is dependent inside of her.

- An average weight gain during pregnancy is 11.2 to 15.9 kg or 25 to 35 lbs.

- For a more precise estimation of adequate weight gain, compute using the body mass index , which is the ratio of weight to height.

- Weight gain during pregnancy occurs due to fetal growth and accumulation of maternal stores.

- On the first trimester, approximately 0.4 kg or 1 lb per month weight gain is recommended.

- On the last two trimesters, a weight gain of 0.4 kg or 1 lb per week is recommended.

- Excessive weight gain occurs with 3 kg or 6.6 lbs of weight gain per month during the last two trimesters.

- A weight gain of less than 1kg or 2.2 lbs in the second and third trimesters is less than usual.

Nutrition for the Pregnant Woman

- The DRI or Dietary Reference Intake of calories of women of childbearing age is 2200.

- For pregnant women, an additional of 300 calories for a total of 2500 calories is recommended.

- This addition in calories provides more energy to the fetus and an elevated metabolic rate to the woman.

- Advise woman to obtain calories from complex carbohydrates like cereals and grains because these are digested more slowly to regulate glucose and insulin .

- Encourage women to prepare healthy snacks such as carrot sticks, cheese, and crackers at the start of the day.

- Assess the weight that the woman is gaining so you can determine if the woman’s caloric intake is adequate.

- Advice the woman not to restrict caloric intake as the fetus is rapidly growing in the final weeks.

- The DRI for protein in women is 46g/d.

- If protein needs are met, overall nutritional needs are met as well except for vitamins C, A, and D.

- Vitamin B12 is found in animal protein; therefore inadequate protein means vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Complete protein or protein that contains the nine essential amino acids can be found in meat, poultry, fish, eggs, yogurt, and milk.

- Incomplete protein or the protein that does not contain all essential amino acids comes from non animal sources.

- When the woman has a history of hypercholesterolemia, advise her to consume lean meat, olive oil, and to remove the skin from poultry.

- Milk is also a rich source of protein, and for women who are lactose intolerant, she can add lactase supplement, take calcium supplements, or buy lactose-free milk.

- Yogurt or cheese can also be a substitute for milk.

- Linoleic acid is a fatty acid that cannot be manufactured by the body and must therefore be obtained from other sources.

- Vegetable oils such as olive, corn, and safflower contains linoleic acid that must be consumed by the pregnant woman.

- Advise the woman to avoid animal fats such as butter.

- Encourage intake of omega-3 oils found in fish, omega-3 fortified eggs, and spreads.

- Vitamin D which is essential for calcium absorption, when lacking in a pregnant woman would result to diminished maternal and fetal bone density.

- Lack of vitamin A results in tender gums and poor night vision .

- Advise the woman to consume plenty of fruits and vegetables and her daily prenatal vitamins to meet the daily vitamin intake requirements.

- Advise the woman not to use mineral oils as laxative because it prevents the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins.

- Folic acid is important for the production of red blood cells and can be found mostly in fresh fruits and vegetables.

- Calcium and phosphorus is needed for bone and teeth formation and should be consumed by the pregnant woman.

- The woman needs to ingest iodine for the proper functioning of the thyroid gland, and it is most commonly found in seafood.

- The DRI for iron for pregnant women is 27 mg, so the woman must ingest foods rich in iron and iron supplements to build more hemoglobin for the fetus.

- Sodium maintains fluid in the body, so it is advisable for the pregnant woman to continue adding salt into her food if not restricted.

- Advise the woman to drink extra amounts of water to promote kidney function.

- Encourage intake of 2 to 3 glasses of fluid daily over three servings of milk.

- To prevent constipation, encourage the woman to eat plenty of fruits and green, leafy vegetables to provide fiber.

- Fiber can also lower cholesterol levels and removes carcinogenic contaminants from the intestine .

- The hair is shiny and strong with good body.

- The woman has good eyesight especially at night; the conjunctivae are moist and pink.

- There are no cavities in the teeth, no swollen or inflamed gingiva, no cracks or fissures at the corners of the mouth , the mucous membranes are moist and pink, the tongue is smooth and non tender.

- The neck has a normal contour of the thyroid gland.

- The skin is smooth with normal color and turgor, no ecchymosis and petechiae present.

- The extremities have a normal muscle mass and circumference; normal strength and mobility , and edema are minimal.

- The fingernails and toenails are smooth, pink, and normal in contour.

- The weight should be within normal limits of ideal weight before the pregnancy.

- The blood pressure is within normal limits for length of pregnancy.

The woman must stay healthy through the entirety of her pregnancy, and most of the nutrients she needs come from food sources. Proper health and nutrition education should be discussed by the healthcare provider to ensure that the pregnant woman is getting the right amount of nutrients that she and the fetus needs.

First Prenatal Visit

The pregnant woman’s first prenatal visit should be the building block of a healthy, happy pregnancy. Everything is established during the first visit, such as the assessment , whether the pregnancy is confirmed, and a little bit of planning for the future. It’s time to focus on the woman herself and the details that could make or break her pregnancy glow.

Initial Interview

- The first prenatal interview could take a long time, so the person who is scheduling appointments for the visits should make the woman aware to avoid cancelling of appointments or rushing of the interview because the woman has an errand to attend to.

- It is important that the healthcare provider should establish rapport even on the first visit because information such as what the woman feels about her pregnancy and if she has any fears can only be taken once the woman trusts her healthcare provider.

- Personal interviews can also make the woman feel important and that she is not just one of the patients that would immediately be forgotten after the visit.

- The interview must take place in a private, quiet environment because it would be difficult for the woman to answer all the questions when you are in a sitting room full of waiting patients or on the hallway.

- The woman must also understand your role in the assessment , because if she views you only as the interviewer you would only get superficial information from her.

- One of the purposes of the initial interview is to assess the health history of the pregnant woman.

- Establishing a baseline health data is crucial especially when there is a new symptom that arises from the woman and it could only be identified as new based on the data gathered from her health history.

- The demographic data are the superficial data that can be obtained from the woman.

- These include the name, age, address, telephone number, and health insurances.

- The chief concern of the woman when she visits the clinic is she thinks she might be pregnant.

- Assess the first day of the last menstrual period of the woman.

- Assess any early signs of pregnancy such as nausea and vomiting , fatigue , and breast tenderness.

- Inquire if she has tried any home pregnancy test kit or had a pregnancy test from a clinic to establish her pregnancy.

- It is important to assess any past illness because it might become active during or after the pregnancy.

- Assess if there are any infections from the past, especially sexually transmitted diseases so you could educate the woman and suggest any vaccines available.

- There are vaccines that are not friendly for a pregnant woman; however, vaccines such as influenza and poliomyelitis can be administered.

- Assess any allergies present even before pregnancy to avoid triggers that could also affect the fetus.

- Assess the presence of family illnesses such as hypertension , diabetes , or asthma on both the father and mother.

- There are illnesses that could become a potential problem during pregnancy or one that could be transferred to the fetus.

- Assess the woman’s current nutrition profile, or ask her to have a 24-hour recall to obtain nutrition information.

- Assess the frequency, type, and amount of exercise she does to determine if her pattern of activities is still recommended during pregnancy.

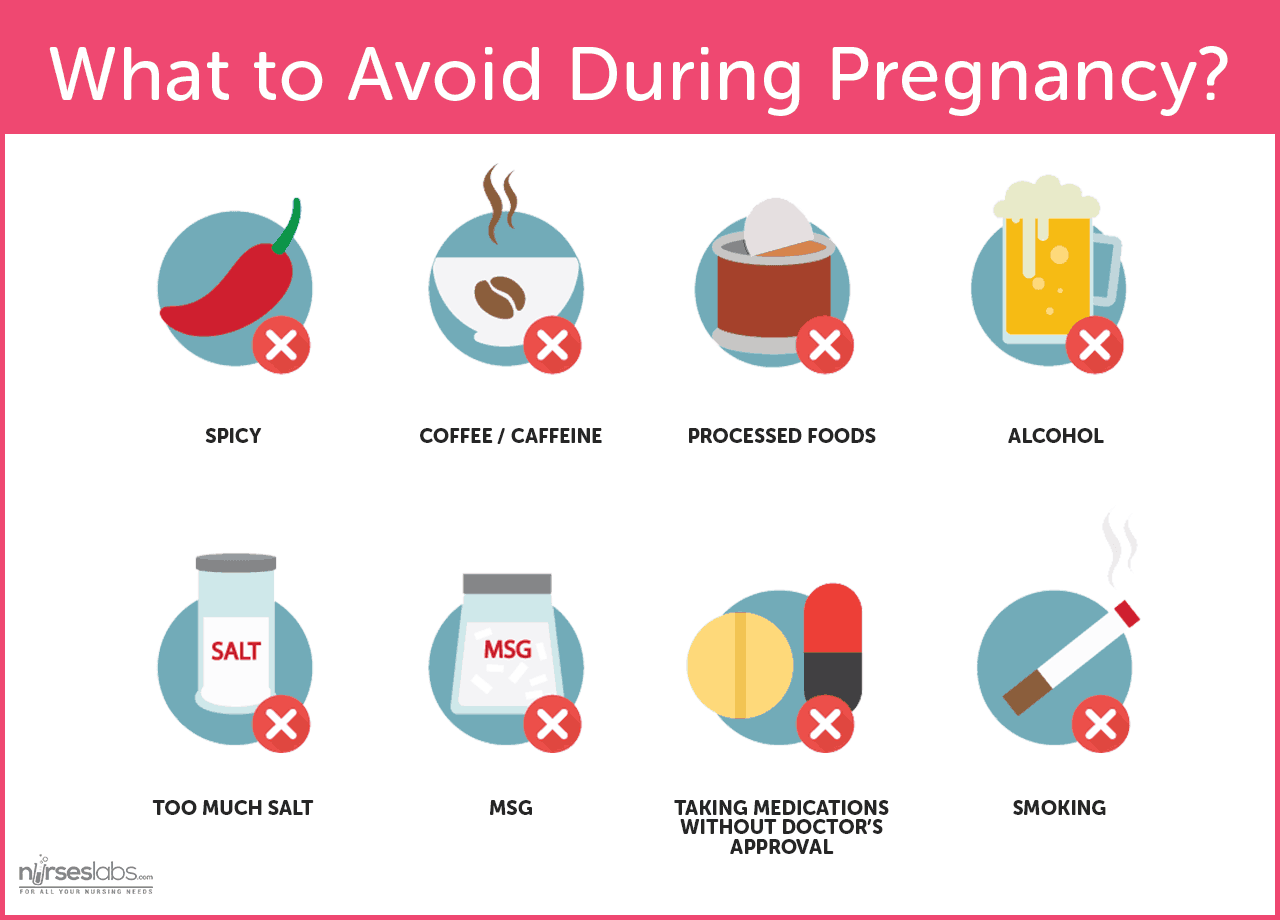

- Assess if the woman smokes or drinks, its frequency, and amount because these vices could cause fetal alcohol syndrome or preterm birth.

- Assess history of medication intake and what medication the woman is taking during pregnancy to determine its possible effects on the fetus.

- Obtain the age of the woman’s menarche, her usual cycle, the duration, and the amount of menstrual flow.

- Assess any past reproductive tract surgery as it can affect the present pregnancy, such as tubal surgery from ectopic pregnancy .

- Assess the reproductive planning method that the woman used or will be using after pregnancy, and also her sexual history to educate her about safe sex practices.

- Assess the woman’s pregnancy history using GTPALM .

- G is the gravid classification or the number of times the woman became pregnant.

- T is the number of full term infants born.

- P is the number of preterm infants born.

- A is the number of miscarriages or therapeutic abortions.

- L is the number of living children .

- M refers to multiple pregnancies.

- Assess the woman’s respiratory system , if she is currently experiencing cough , asthma , pain upon breathing, or any serious respiratory illnesses such as tuberculosis .

- Assess the cardiovascular system and any history of heart murmurs, heart diseases, hypertension , and if she knows her blood pressure level and any experience of blood transfusion .

- Assess her gastrointestinal system ; ask about her pre-pregnancy weight, any discomforts such as vomiting , diarrhea or constipation, hemorrhoids, and changes in bowel habits.

- Assess her genitourinary system and ask about any urinary tract infections, STIs, PIDs, any difficulties in conceiving, and hematuria .

- Assess any breast lumps, secretions, pain upon palpation of the breast, or tenderness.

- Assess the woman’s last dental exam, the use of any dentures, the condition of the teeth, and if she is experiencing any difficulty in swallowing.

Laboratory Assessment

Papanicolaou smear (pap smear).

- Pap smear is performed to detect and diagnose the presence of precancerous and cancerous conditions of the cervix, vulva, or vagina.

- The test also reveals infectious diseases and inflammation.

- The classification of Pap smear can be seen in the Bethesda classification of Pap smears.

- Women who have multiple sexual partners, smoke cigarettes, have a history of HPV, and sexually active before 21 years old should have Pap smear done more frequently.

- Complete blood count should be taken to assess the hemoglobin, hematocrit, and red cell index and determine the presence of anemia .

- White blood cell count and platelet count must also be obtained to assess for infection clotting ability.

- Blood typing with Rh factor is also important because blood needs to be available if ever the woman experiences bleeding during pregnancy.

- Maternal serum alpha fetoprotein detects birth defects such as neural tube defects if elevated and chromosomal anomalies if decreased.

- Antibody titers for rubella and hepatitis B or HBsAG determine whether the woman is protected against rubella and if the newborn would have a chance of developing hepatitis B.

- A woman with a history of diabetes , large for gestational age babies, obese, or has glycosuria should undergo glucose tolerance test.

- A 50-g oral toward the end of the first trimester should be performed to rule out gestational diabetes .

- The plasma glucose level should not exceed 140mg/dl at 1 hour.

- Urinalysis is performed to assess proteinuria, glycosuria, and pyuria.

- These can be done through test strips or microscopic examination of the urine.

- To confirm pregnancy, an ultrasound must be scheduled especially if the woman is unsure of the date of her last menstrual period.

- Ultrasonography would also determine the growth of the fetus, but only the gestational sac would be seen at this stage.

Childbirth Education

Most expectant parents, especially the first timers are eager yet anxious to know the rules to becoming a parent even before the birth of their child. There are several courses or classes for parents regarding childbirth that would fill up the gap of knowledge that the couple is yearning for.

- The birth of childbirth education started in the early 1900s to encourage women to involve themselves in prenatal care .

- It progressed because of the additional birth choices that emerged later on.

- The goal of childbirth education is to prepare expectant parents physically, mentally, and emotionally for childbirth.

- Childbirth educators have a professional degree and a certificate from a childbirth education course.

- Some of the topics that childbirth educators teach are the physical and emotional aspects of pregnancy, early parenthood and coping skills, and labor support techniques.

- Childbirth classes are mostly taught in group; and today there are instructors who also employ the use of slides, videotapes, and demonstrations.

- Childbirth education is more effective if both the parents are interactive, as they would be able to share their fears and hopes about the pregnancy and learn together as a couple.

- A lot of studies have been conducted regarding the efficacy of childbirth classes when it comes to pain reduction, shortening the length of labor, decreasing the amount of medication used, and the increase of enjoyment in the overall experience of childbirth.

- It is now generally accepted that childbirth courses could increase the satisfaction and control of feelings and reduce the amount of pain felt during childbirth.

The Childbirth Plan

- The childbirth plan consists of the choice of setting, birth attendant, birthing positions, medication options, and plans for immediate postpartum , etc.

- Classes encourage the couple to write a birth plan and deal with these issues before the day of birth to avoid stressing out at the last minute.

- Make sure that the couple also understands that the birth plan should be flexible in case some complications may arise.

- Preconception classes are classes for couples who are planning to get pregnant within a short span of time.

- These couples most likely want to learn more about what they can expect in a pregnancy and what could be their possible birth setting and procedure choices.

- The class includes recommendation of preconception nutrition changes and physical and psychological changes that pregnancy brings.

- Overall, preconception classes emphasize the importance of pre-pregnancy preparations to ensure a healthy fetus and mother.

- Expectant parenting classes are for couples who are already pregnant and expecting.

- The focus of the topics is on the family health, nutrition during pregnancy, health changes during pregnancy, and newborn care .

- Pregnant women come to these classes accompanied by their support persons, and the class usually lasts for 4 to 8 hours over a 4 to 8-week period.

- The classes are individualized for each group according to their special needs, such as for adolescent pregnancy, pregnant women with disabilities, or expectant adoptive parents.

- Sibling classes are designed for older brothers and sisters to give them awareness of what would happen during birth and what they can expect a newborn would act like.

- Simple things that a child can do during the period of pregnancy, such as eating nutritious food together with their mother and how babies grow are taught in these classes.

- The information given during sibling classes should be appropriate to their age to make sure that the classes are effective.

- Women who take breastfeeding classes appreciate over time the importance of breastfeeding and the advantages it gives both the mother and the baby.

- Topics include the physiology of breastfeeding, its psychological aspects, and the advantages of exclusive breastfeeding.

- The classes would also emphasize on ways on how a busy mother could still breastfeed her child despite a busy work schedule so the breastfeeding could continue for at least the first full year of the baby.

- The focus of preparation for childbirth classes is mainly in the birth process.

- The class would help the woman and her support person prepare for the childbirth experience.

- Pain management and reduction is also a part of these classes, both with nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic measures.

Pain Management During Labor

- Also known as the Partner-Coached Method, it centers on the idea that the woman’s partner should play an important role during pregnancy, labor, and childbirth until early newborn care.

- Originated by Robert Bradley, it sheds light on the fact that pregnancy and birth are joyful natural processes.

- The woman is taught to use an internal focus point as a disassociation technique, and she is encouraged to walk during labor.

- This is a method proposed by Grantly Dick-Read wherein the premise is that fear leads to tension, which leads to pain.

- The idea is for the woman to prevent the fear and break the chain between tension and pain, so she can reduce the pain of labor contractions.

- Lack of fear is achieved through education on childbirth and relaxation , and pain management techniques.

- The Lamaze Method is one of the most widely taught methods in the United States.

- The theory is based on stimulus-response conditioning, wherein women can learn to use controlled breathing to reduce the pain of labor.

- Formal classes are organized by Lamaze International or the International Childbirth Education Association.

- Topics from Lamaze include prenatal nutrition and exercises, common discomforts of pregnancy, and information to prepare couples for unexpected circumstances such as cesarean birth or the need for anesthesia .

- The gating control theory of pain is emphasized in Lamaze where the use of controlled breathing and imagery can block incoming pain sensations.

- Lamaze classes are kept small so that there would be enough time for individualized instruction and attention to each couple.

- The support person that the woman brings would act as her coach in labor.

The Birth Setting

One of the most important choices that a couple should also consider is the birthing center where their baby would be delivered. Choosing the place where the woman would give birth depends on the health of both the fetus and the mother, and should be in accordance with the preferences of the kind of assistance the couple would want during delivery.

Hospitals have not always been the place for birth. In earlier times, childbirth always takes place at home without any analgesia and the women give birth the natural way. However, today a lot of birthing choices were developed, and birthing centers have become hospitals instead of at home.

- Women are still given the freedom to choose where they would want to give birth provided that the woman does not have a complicated pregnancy, and the health of the fetus is stable.

- Women who have complicated pregnancies have less freedom in choosing that the usual because they are advised to give birth only at hospitals for provision of emergency care if needed.

- Birthing centers are now fully equipped with resources that could compete with hospital facilities, which is why most couples consider giving birth here than going to the hospital.

Most women who give birth are always attended to by their physicians or obstetricians. But as there are more and more courses offered for family practitioners to become certified birth attendants, even with only a midwife or nurse -midwife to attend to a birth is now considered as appropriate and preferred by couples.

- Alternative birthing centers employ more nurse-midwives to attend to births.

- Another consideration that a woman should make is who would become her support person during labor up until her delivery.

- In the past, experienced women in the community take up the role of the support person.

- Later on, support persons became the father of the baby.

- Today, any family member may take up the role of a support person.

- Doulas are also preferred by more women today, as an addition to their support person.

- Doulas are women who are specially prepared to assist with childbirth, and they are helpful especially when the support person would find it hard to provide enough support during labor.

- When a woman’s support person becomes too emotional to assist the woman in labor, the doula could take in charge to allow the father or any support person to enjoy the experience and involve them emotionally in the situation.

- The support of the doula can also reduce the rates of cesarean births, epidural anesthesia , and oxytocin augmentation, according to some research.

Hospital Birth VS Alternative Birthing Centers

Hospital birth has always been preferred by women when they want to ensure their safety during delivery and to be certain that the baby would be handled by professionals. However, the emergence of alternative birthing centers gave women the chance to choose which setting they would want to give birth in, as both could have advantages and disadvantages to consider.

- Hospitals have standards when it comes to their maternity services as influenced by the First Consensus Initiative of the Coalition for Improving Maternity Services.

- The organization provides a set of practices that would make a hospital mother and baby friendly.

- The mother should be able to consider her experience as healthy and joyous regardless of her age or circumstances.

- The mother should have access to a full range of options regarding her pregnancy, birth, and care of the newborn.

- The mother should receive utmost support when it comes to her birthing choices based on her beliefs or culture.

- The mother should be allowed to give birth in any environment where she would feel safe and secure.

- The mother should receive information and updates about anything that could affect her pregnancy and her baby, with the rights to informed consent and refusal.

- At hospitals, women are encouraged to control the discomfort and pain of labor through nonpharmacological measures despite the availability of epidural anesthesia .

- Information is readily given to women regarding the birthing process and to help her decide on procedures that would be performed.

- Breastfeeding is highly encouraged at hospitals to promote bonding between the mother and the baby and to aid in uterine contractions.

- Labor, birth, and postpartum care can be done in one single room at hospitals which could provide more ease and comfort for the woman.

- Skilled professionals attend to the woman during birth, and emergency care is readily available if the situation warrants it.

- However, the family and the woman might be separated for one night during delivery, and the mother may sometimes feel that she is not in full control of her experience.

- Alternative birthing centers are wellness-oriented childbirth facilities that encourage birth outside of the hospital setting while still being able to provide medical resources appropriate for any emergency that might arise.

- Nurse-midwives attend to the birth at ABCs.

- Before a woman is permitted to give birth at an alternative birthing center, she is screened for complications first to avoid increasing the mortality rate of mothers and infants in this setting.

- Women are also encouraged to deal with labor pain through nonmedical measures.

- Family members are allowed to accompany the woman throughout the experience.

- Skilled professionals attend to the woman during birth, and emergency care is also readily available.

- High-risk care may not be easily and immediately arranged at alternative birthing centers.

- The stay of the woman at the facility may only be brief, so fatigue is most likely encountered after birth.

- The woman is also expected to monitor her postpartal status independently because of her brief stay in the healthcare setting.

- Women remain at the ABC 4 to 24 hours after birth because the woman can recover quickly because of the minimum analgesia used.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Pregnancy week by week

1st trimester pregnancy: What to expect

The first trimester of pregnancy can be overwhelming. Understand the changes you might experience and how to take care of yourself during this exciting time.

During the first few months of pregnancy, amazing changes happen quickly. This part of pregnancy is called the first trimester. Knowing what physical and emotional changes to expect can help you face the months ahead with confidence.

Your first symptom of pregnancy might have been a missed period. But you can expect other physical changes in the coming weeks, including:

- Tender, swollen breasts. Soon after you become pregnant, hormonal changes might make your breasts sensitive or sore. You'll likely have less discomfort after a few weeks as your body adjusts to hormone changes.

- Avoid having an empty stomach. Eat slowly and in small amounts every 1 to 2 hours.

- Choose bland foods that are low in fat. Some examples are bananas, rice, applesauce and toast. Include lean proteins such as low- or no-fat dairy, nuts, nut butters and seeds.

- Foods that contain ginger might help settle your stomach.

- Stay away from foods or smells that make your upset stomach worse.

- Sip plenty of cold, clear fluids.

Call your healthcare professional if your upset stomach or vomiting becomes worse.

- More urination. You might find yourself urinating more often than usual. The amount of blood in the body increases during pregnancy. This causes the kidneys to process extra fluid that ends up in the bladder.

- Fatigue. It's common to feel very tired during early pregnancy as levels of the hormone progesterone rise. Rest as much as you can. Take a 15-minute nap during the day if you can. A healthy diet and exercise might boost your energy.

- Food cravings and dislikes. When you're pregnant, your sense of taste might change. Some smells may seem stronger too. To help, try using a fan when you cook. Ask a family member or partner to take out the trash if possible. Like most other symptoms of pregnancy, food preferences are due to hormone changes.

- Eat small, frequent meals.

- Sip drinks in between meals.

- Don't eat fried foods, citrus fruits, chocolate or spicy foods.

- Don't lie down right after a meal.

- Try not to eat or drink within a few hours of going to bed.

Talk with your healthcare professional if these steps don't give you enough relief. Safe medicines are available for heartburn.

Constipation. High levels of the hormone progesterone can slow the movement of food through the digestive system. This can cause fewer or painful bowel movements. So can the growing uterus, which may put pressure on the bowels.

To prevent or relieve constipation, eat plenty of foods with fiber. These include fresh or dried fruit, raw vegetables, and whole-grain cereals and bread. Drink lots of fluids too, especially water and prune juice or other fruit juices. Cut back on drinks with caffeine. Regular physical activity also helps. Talk with your healthcare professional about stool softeners if needed.

Your emotions

Pregnancy might make you feel delighted, anxious, excited and exhausted — sometimes all at once. Even if you're thrilled about being pregnant, a new baby can add stress to your life.

It's natural to worry about your baby's health, your adjustment to parenthood and the financial demands of raising a child. If you're employed, you might worry about how to balance the demands of family and career. You also may have mood swings. What you're feeling is common. Take care of yourself and look to loved ones for understanding and support. If your mood changes become serious or intense, see your healthcare professional. Also get a checkup if you feel moody, sad or overwhelmed for longer than two weeks.

Prenatal care

You might choose to get care from various healthcare professionals during your pregnancy. These professionals may include a family doctor, obstetrician, nurse-midwife or other pregnancy specialist. Whoever you choose to see, your healthcare professional can treat, educate and reassure you throughout your pregnancy.

Your first pregnancy checkup focuses on:

- Checking your overall health.

- Finding any risk factors that could affect the health of you or your baby.

- Figuring out how far along the pregnancy is, also called your baby's gestational age.

Your healthcare professional asks detailed questions about your health history. Be honest. If you're not comfortable talking about your health history in front of your partner, schedule a private appointment. Also expect to learn about first trimester screening for chromosomal abnormalities.

You'll likely have checkups every four weeks for about the first 28 weeks of pregnancy. You may need checkups more or less often. It depends on your health and medical history. During these appointments, talk about any concerns you might have about pregnancy, childbirth or life with a newborn. Remember, no question is silly or trivial — and the answers can help you take care of yourself and your baby.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Bastian LA, et al. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of early pregnancy. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Sept. 5, 2023.

- Smith JA, et al. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: Treatment and outcome. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Sept. 5, 2023.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Your Pregnancy and Childbirth: Month to Month. Kindle edition. 7th ed. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2021. Accessed Sept. 5, 2023.

- FAQs: Morning sickness: Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/Morning-Sickness-Nausea-and-Vomiting-of-Pregnancy. Accessed Sept. 5, 2023.

- Lockwood CJ, et al. Prenatal care: Initial assessment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Sept. 5, 2023.

- Pregnancy: Body changes and discomforts. Office on Women's Health. https://www.womenshealth.gov/pregnancy/youre-pregnant-now-what/body-changes-and-discomforts. Accessed Sept. 6, 2023.

- Depression during and after pregnancy. Office on Women's Health. https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/depression-during-and-after-pregnancy. Accessed Sept. 6, 2023.

- Prenatal care and tests. Office on Women's Health. https://www.womenshealth.gov/pregnancy/youre-pregnant-now-what/prenatal-care-and-tests. Accessed Sept. 6, 2023.

- What happens during prenatal visits? Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/preconceptioncare/conditioninfo/prenatal-visits. Accessed Sept. 6, 2023.

- Marnach ML (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Sept. 17, 2023.

Products and Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- Can birth control pills cause birth defects?

- Fetal development: The 1st trimester

- Implantation bleeding

- Nausea during pregnancy

- Pregnancy due date calculator

- Prenatal care: 1st trimester

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- 1st trimester pregnancy What to expect

5X Challenge

Thanks to generous benefactors, your gift today can have 5X the impact to advance AI innovation at Mayo Clinic.

SARAH INÉS RAMÍREZ, MD, FAAFP

Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(2):139-150

Related Letter to the Editor: Rethinking Breastfeeding Guidelines for People Living With HIV

Related Letter to the Editor: Strong Maternal Health Curriculum Needed in Family Medicine

Related AFP Community Blog: Practice Ancestry-Based Medicine, not Racial Essentialism

Related editorial: Perinatal Care of Transgender Patients, Adolescent Patients, and Patients With Opioid Use Disorder

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Well-coordinated prenatal care that follows an evidence-based, informed process results in fewer hospital admissions, improved education, greater satisfaction, and lower pregnancy-associated morbidity and mortality. Care initiated at 10 weeks or earlier improves outcomes. Identification and treatment of periodontal disease decreases preterm delivery risk. A prepregnancy body mass index greater than 25 kg per m 2 is associated with gestational diabetes mellitus, hypertension, miscarriage, and stillbirth. Advanced maternal and paternal age (35 years or older) is associated with gestational diabetes, hypertension, miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction, aneuploidy, birth defects, and stillbirth. Rh o (D) immune globulin decreases alloimmunization risk in a patient who is RhD-negative carrying a fetus who is RhD-positive. Treatment of iron deficiency anemia decreases the risk of preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, and perinatal depression. Ancestry-based genetic risk stratification using family history can inform genetic screening. Folic acid supplementation (400 to 800 mcg daily) decreases the risk of neural tube defects. All pregnant patients should be screened for asymptomatic bacteriuria, sexually transmitted infections, and immunity against rubella and varicella and should receive tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap), influenza, and COVID-19 vaccines. Testing for group B Streptococcus should be performed between 36 and 37 weeks, and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis should be initiated to decrease the risk of neonatal infection. Because of the impact of social determinants of health on outcomes, universal screening for depression, anxiety, intimate partner violence, substance use, and food insecurity is recommended early in pregnancy. Screening for gestational diabetes between 24 and 28 weeks is recommended for all patients. People at risk of preeclampsia, including those diagnosed with COVID-19 in pregnancy, should be offered 81 mg of aspirin daily starting at 12 weeks. Chronic hypertension should be treated to a blood pressure of less than 140/90 mm Hg.

Family physicians provide family-centered care for individuals and families before, during, and after the birth of a child. Well-coordinated prenatal care that follows an evidence-based, informed process results in fewer hospital admissions, improved education, greater care satisfaction, improved perinatal outcomes, and mitigates pregnancy-associated morbidity and mortality. 1 Family physicians are uniquely positioned to address social determinants of health while ensuring quality of care.

Prenatal Care Visits

Initiation of care between six and 10 weeks allows for identification of preexisting conditions that negatively affect maternal-fetal outcomes (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity) 2 ; however, 22% of pregnant patients do not receive care during this time. 2 The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a reevaluation of the number of physician visits needed, with an emphasis on increased flexibility, allowing for a combination of virtual and in-person visits depending on risk. 3 Table 1 outlines the components of prenatal care. 1 , 4 – 22 Table 2 provides opportunities for educating pregnant patients during prenatal care visits. 6 , 8 , 14 – 19 , 23 – 29

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Weight, height, and blood pressure should be measured at the first prenatal visit. Early identification of periodontal disease and treatment decreases adverse pregnancy outcomes. 7 Treatment may be performed in the second trimester, and emergent treatment may be completed at any time during pregnancy. 7 A bimanual pelvic examination has poor predictive value for clinical pelvimetry and screening for disease (i.e., sexually transmitted infections and cancer) but may be used as a diagnostic aid in patients with a discrepancy between uterine size and gestational age, which warrants ultrasonography assessment. 30 A pelvic examination is also useful in a symptomatic patient for evaluating spontaneous labor (e.g., cervical dilation, rupture of amniotic membranes). The clinical breast examination is a diagnostic aid in the symptomatic patient and addresses breastfeeding concerns or barriers but does not demonstrate benefit in patients already receiving screening mammograms and does not decrease mortality. 31 – 33

MATERNAL WEIGHT GAIN AND NUTRITION

A prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) greater than 25 kg per m 2 is associated with preterm delivery, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia. A BMI greater than 30 kg per m 2 is also associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, stillbirth, and obstructive sleep apnea. 6 Prepregnancy BMI informs the timing of fetal surveillance, nutritional counseling, and goals for gestational weight gain. Table 3 lists general dietary guidelines for pregnant people. 8 , 17 , 34 , 35 For Black and Hispanic people, a prepregnancy BMI greater than 25 kg per m 2 and the associated poor outcomes are worse compared with non-Hispanic White people. 36

PARENTAL AGE AT CONCEPTION

Advanced maternal and paternal age (35 years and older) is associated with poor outcomes (i.e., aneuploidy, birth defects, gestational diabetes, hypertension, intrauterine growth restriction [IUGR], miscarriage, and stillbirth). Activities focused on improving perinatal outcomes for this group, such as a detailed fetal anatomic screening on ultrasonography, may decrease morbidity and mortality. 37

PREGNANCY DATING AND ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Accurate gestational age estimation is critical to quality care because it enables more precise timing of interventions (e.g., aspirin for preeclampsia prevention, steroids for fetal lung maturity), screening tests, and delivery. Up to 40% of people estimate their last menstrual period incorrectly; therefore, ultrasonography is recommended if uncertainty exists and for patients with irregular menstrual cycles, irregular bleeding, and discrepancy between uterine size and gestational age. 1 , 38 Ultrasonography before 24 weeks decreases missed multiple gestations and post-term inductions. 39 Although routine third-trimester ultrasonography may increase detection of IUGR, it does not improve outcomes. 40 If malpresentation is suspected on physical examination, confirmation with ultrasonography is recommended. 4

ALLOIMMUNIZATION

For patients who are RhD-negative and carrying a fetus who is RhD-positive, the alloimmunization risk is 1.5% to 2% in the setting of spontaneous abortion and 4% to 5% with dilation and curettage. The risk is decreased by 80% to 90% with anti-D immune globulin. 41 Testing for the ABO blood group and RhD antibodies should be performed early in pregnancy. A 300-mcg dose of anti-D immune globulin is recommended for RhD-negative pregnant patients at 28 weeks and again within 72 hours of delivery if the infant is RhD-positive. 41

Iron deficiency anemia increases the risk of preterm delivery, IUGR, and perinatal depression. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of screening for anemia in pregnancy. 42 Screening is recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists early in pregnancy, with iron treatment if deficient. 43 Intravenous iron should be considered for patients who cannot tolerate oral iron or in whom oral iron has been ineffective at correcting the deficiency. 43 Patients with non–iron deficiency anemia, or if iron repletion is ineffective within six weeks, should be referred to a hematologist for further evaluation. Iron supplementation in the first trimester decreases the prevalence of iron deficiency. 43

INHERITED CONDITIONS

Pregnant patients should be counseled and offered aneuploidy (extra or missing chromosomes) screening in early pregnancy, regardless of age. 44 In the United States, 1 in 150 infants has a chromosomal condition, the most common being trisomy 21 (Down syndrome). 44 Table 4 compares screening tests for Down syndrome. 1 , 45 , 46 If a screening test is positive, amniocentesis at 15 weeks or more or chorionic villous sampling between 11 and 13 weeks is recommended. Both procedures have similar rates of fetal loss. 47 At 35 years of age, the risk of Down syndrome (1 in 294 births) is similar to that of fetal loss from amniocentesis. 47 Serum and nuchal translucency testing can screen for other trisomies, including 13 and 18, the protocols for which have lower sensitivities and higher specificities compared with screening protocols for trisomy 21 because they are rarer. 47

Additional genetic screening should be based on maternal and paternal personal and family histories. Race is a social construct, necessitating a shift in genetic risk stratification from race-based to ancestry-based. Sickle cell disease affects up to 100,000 people in the United States, but its inheritance pattern (1:10) is based on people with African ancestry, which includes much of the world. 48 Cystic fibrosis is inherited mainly by people of European ancestry (1:25), but ignoring the possibility of European ancestry in certain racial and ethnic groups results in an underestimation of its prevalence: African (1:61), Hispanic (1:40), and Mediterranean (1:29). 49

NEURAL TUBE DEFECTS

In the United States, neural tube defects affect approximately 2,600 infants per year, with the highest prevalence in Hispanic populations. 35 , 50 All pregnant patients should be counseled and offered screening with maternal serum alpha fetoprotein. 35 Folic acid, 400 to 800 mcg daily, started at least one month before conception and continued until the end of the first trimester, decreases the incidence of neural tube defects by nearly 78%. 35 Patients taking folic acid antagonists (e.g., carbamazepine, methotrexate, trimethoprim) or who have a history of carrying a fetus with a neural tube defect should take 4 mg of folic acid daily, starting at least three months before conception. 35

THYROID DISORDERS

There is no evidence that screening for thyroid disorders improves pregnancy outcomes. Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels should be measured if there is a history of thyroid disease or symptoms of disease. If the level is abnormal, a free thyroxine test helps determine the etiology. 51 Hypothyroidism complicates 1 to 3 per 1,000 pregnancies and increases the risk of fetal loss, preeclampsia, IUGR, and stillbirth. Hyperthyroidism occurs in 2 per 1,000 pregnancies and is associated with miscarriage, preeclampsia, IUGR, preterm delivery, thyroid storm, and congestive heart failure. 51 The effect of subclinical hypothyroidism on a child's neurocognitive development is not well understood, and the effectiveness of treatment with levothyroxine is unproven. 51

CERVICAL CANCER

Intervals for cervical cancer screening are based on patient age, cytology history, and history of the presence of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV). Routine screening for people at average risk of cervical cancer should begin at 21 years of age. Screening can be performed with either cytology alone every three years, HPV screening alone every five years, or cytology plus HPV screening every five years starting at 25 years of age. Screening is not indicated for people 65 years and older with negative screening in the previous 10 years, and no history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or higher in the past 25 years. 52 Colposcopy is indicated when the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 is greater than 4%. Surveillance of high-grade lesions should be performed every 12 to 24 weeks. 52 , 53 Although colposcopy and cervical biopsy can be safely performed during pregnancy, endocervical sampling should be deferred until postpartum. 53

Infectious Disease

Bacteriuria.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria complicates up to 15% of pregnancies in the United States, 30% of which progress to pyelonephritis if untreated. 54 All pregnant patients should be screened for bacteriuria at the first prenatal visit. 54 A culture from a midstream or clean-catch sample with greater than 100,000 colony-forming units per mL of a single pathogen is considered positive and treated to decrease the risk of pyelonephritis and subsequent preterm delivery. 54

SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

Sexually transmitted infections can affect prenatal outcomes. 55 – 57 Table 5 lists routine screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections in pregnancy. 55 , 56

Rubella immunity screening during the first prenatal visit is recommended. Postpartum vaccination should also be offered if the patient is not immune to prevent congenital rubella syndrome in subsequent pregnancies. 1 , 58 The presence of rubella immunoglobulin G should be interpreted with caution in patients recently migrating from areas where rubella is endemic because this may indicate a recent infection. 58 Rubella is a live vaccine and should not be administered during pregnancy but is safe during lactation after delivery. 59 , 60

Maternal varicella can result in congenital varicella syndrome (i.e., IUGR and limb, ophthalmologic, and neurologic abnormalities) and neonatal varicella; infection can occur from approximately five days before to two days after birth. A negative history of varicella infection or vaccination warrants serologic testing, and if immunoglobulin G is negative, varicella exposure should be avoided. Postpartum vaccination should be offered. 61

Although tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccination is recommended for anyone in close contact with the infant, only antenatal maternal vaccination ensures increased protection against neonatal pertussis. 62 Pregnant patients should receive a Tdap vaccine beginning at 27 weeks to maximize time for passive immunity to the fetus through the placental transfer of maternal antibodies; vaccination is recommended in each subsequent pregnancy. 62

INFLUENZA AND COVID-19

Influenza and COVID-19 infection in pregnancy increase the risk of intensive care unit admission, preterm delivery, stillbirth, and maternal death. 63 , 64 COVID-19 infection almost doubles the risk of developing preeclampsia 64 ; therefore, initiating low-dose aspirin (81 mg daily) starting at 12 weeks should be considered. 5 Pregnant patients and their household contacts should be vaccinated for influenza and COVID-19. 63 , 64

GROUP B STREPTOCOCCUS

In the United States, group B Streptococcus (GBS) is the leading cause of infection in the first three months of life; 25% of all pregnant patients are GBS carriers. 65 , 66 Screening with a vaginal-rectal swab for culture between 36 and 37 weeks is recommended. 67 Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis decreases neonatal mortality. Antibiotics are recommended when there is GBS bacteriuria with the current pregnancy, a history of a previous infant affected by GBS (e.g., septicemia, meningitis, pneumonia, death), or unknown GBS status and risk factors (e.g., preterm labor, rupture of membranes more than 18 hours before delivery, GBS in previous pregnancy). 67 Patients with GBS bacteriuria in the current pregnancy are assumed to be colonized and do not need subsequent screening. 67

Social Determinants of Health