Where will your education and career journey take you?

Monday 6 July 2020

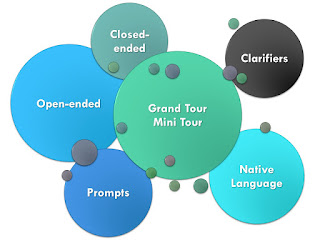

Different types of interview questions.

- Open-ended questions : "relevant and meaningful" which "invite thoughtful, in-depth responses that elicit whatever is salient to the interviewee", not the interviewer (Patton, 2014, p. 631)... which is why we need all the following options to create a sound set of interview questions. Open-ended questions "have no definitive response and contain answers that are recorded in full" (Gray, 2004, p. 194)

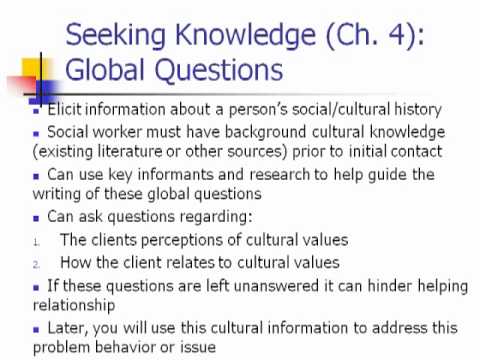

- Grand Tour questions : these are large, sweeping, general questions asking the interviewee to describe the 'terrain' of their experience, where we learn "native terms about [the] cultural scenes" we are seeking to understand (Spradley, 1979, p. 86). Grand tour questions can be scoped to focus on "space, time, process, a sequence of events, people, activities or objects" (Spradley, 1979, p. 87). The same approach can be used in smaller, 'mini' grand tours. There are a number of types of grand - or mini - tour question sub-types:

- Typical , e.g., "Could you describe a typical day at the office?" (Spradley, 1979, p. 87)

- Specific , e.g., "Tell me what you did yesterday, from the time you got to work until you left?" (Spradley, 1979, p. 87)

- Guided , e.g., "Could you show me around the office?" (Spradley, 1979, p. 87)

- Task-related (Spradley, 1979), e.g., Could you compile the report and show me what you do where? This can lead to clarifiers

- Clarifiers : questions such as "What are you doing now?" and "what is this?" can be used to prompt in Grand tour questions, particularly in Task-related questions (Spradley, 1979, p. 87)

- Native language questions : "are designed to minimize the influence of [interviewee's] translation competence", where we ask "How would you refer to it?" about making typing mistakes of a secretary to check our understanding of a particular act, role, person or process, they might answer "I would call them typos" (Spradley, 1979, p. 89)

- Prompts : are short questions to the interviewee so they refine the initial answer, and "sharpen their thoughts to provide what can be critical definitions or understandings" (Guest et al., 2012, p. 220). There are a number of sub-types:

- Direct Prompts : these are where the "interviewer asks clearly, 'What do you mean when you say X?' or 'Can you give an example of Y?' Probes may also be statements: 'Tell me more about that,' or 'Explain that to me a little bit'" (Guest et al., 2012, p. 220).

- Indirect prompts : these keep the interview moving by keeping "the interviewee talking and encourage further explanation without asking another question". These might be non-verbal, such as head nodding or smiling; or verbal, such as "mmm hmm", or "yes" (Guest et al., 2012, p. 219).

- Silent prompts : "just remaining quiet and waiting for an [interviewee] to continue" (Bernard, 2011, p. 162). Although Guest et al., suggest this is an indirect prompt (2012), I think that silence is more powerful a tool than being only an indirect prompt: silence can convey camaraderie, empathy, reminiscence, unfinished business, waiting, and create a void that most will step forward to fill.

- Echo prompts : there are "particularly useful when an informant is describing a process, or an event. 'I see. The goat’s throat is cut and the blood is drained into a pan for cooking with the meat. Then what happens?' This probe is neutral and doesn’t redirect the interview. It shows that you understand what’s been said so far" (Bernard, 2011, p. 162).

- Closed ended-questions : where the answer is dichotomous (yes, or no), or some form of 'fixed' choice answers via an option list or a Likert scale. These questions are most often used in surveys (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2008), but can be useful to get people started on a topic, to end a topic, or to provide a particularly structured answer that enables the interviewer to transition into a new area. Closed-ended questions tend to "restrict the richness of alternative responses, but are easier to analyse." (Gray, 2004, p. 195)

- Bernard, H. R. (2011). Research Methods in Anthropology Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (5th ed.). AltaMira Press

- Gray, D. E. (2004). Doing Research in the Real World . SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Guest, G., Namey, E. E., & Mitchell, M. L. (2012). Collecting Qualitative Data: A field manual for applied research . SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and Evaluation Methods (4th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Spradley, J. P. (1979). The Ethnographic Interview. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2008). Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . SAGE Publications, Inc.

No comments :

Post a comment.

Thanks for your feedback. The elves will post it shortly.

support your career

get the interview & get the job

Example Questions to Ask in an Ethnographic Interview

MIN 5218 Preparing the Ethnographic Interview

What does culture mean to you?

Culture alludes to the total store of information, experience, convictions, values, perspectives, implications, progressions, religion, ideas of time, jobs, spatial relations, ideas of the universe, and material items and assets obtained by a gathering of individuals throughout ages through individual and gathering endeavouring.

Culture is the framework of information shared by a generally enormous gathering of individuals.

The Right Questions: Ethnographic Questions

Ethnographic interviews employ descriptive and structural questions. Descriptive questions are broad and general and allow people to describe their experiences, their daily activities, and objects and people in their lives. These descriptions provide the interviewer with a general idea of how individuals see their world. Structural questions are used to explore responses to descriptive questions. They are used to understand how the client or parent organizes knowledge. Interviews begin with descriptive questions, such as those shown in the sidebar on page 5. Typically, the interviewer begins with a grand tour (“Tell me about a typical day”) or mini-tour questions (“Tell me about a typical mealtime” or “Tell me about a typical therapy time”).

Responses to the descriptive questions will enable the interviewer to discover what is important to clients or their families. As interviewers listen to answers to descriptive questions, they begin to hear words or issues repeated. These words or issues represent important categories of knowledge. The interviewer wants to understand the relationships that exist among these categories. Nine relationships can capture the majority of the relationships that exist in people’s lives (see sidebar, below right, for examples of each type of structural question). For example, Sarah frequently mentioned being “overtaxed.” The interviewer then asked structural questions to explore Sarah’s concept of being overtaxed. “What kinds of things do you do when you are feeling overtaxed?” “What are the reasons you are overtaxed?” “What are ways to keep from being overtaxed?”

The strict inclusion, rationale, and means-ends questions tend to be used the most. As you begin to do ethnographic interviews, these three types of structural questions are good ones to learn first. Strict-inclusion questions help you gather information on the categories a person is using to organize information (e.g., kinds of memory problems Sarah experiences, kinds of activities Jay wants to participate in). Means-end questions lead to information on behaviors (e.g., ways Sarah deals with feelings of isolation, ways Dora deals with Paul’s tantrums). Rationale questions lead to information on causes of or reasons for the behavior (e.g., reasons for Sarah’s feeling overtaxed, reasons that Jay rejected hearing aids as a child, causes of Paul’s tantrums).

By conducting an ethnographic interview, the interviewer is attempting to gain a good understanding of the social situations in which clients and their families exist and how they perceive and understand those situations. Every social situation has nine dimensions that include people involved, places used, individual acts, groups of acts that combine into activities or routines, events, objects, goals, time, and feelings. Although these dimensions can be discussed separately, in real life, the dimensions interact. People engage in acts, activities, and events in places using objects associated with the activities, events, and locations. The activities and events generally have a time sequence. People engage in them for a reason—that is, they have goals for doing what they do, and they have feelings for what they do, where they do it, and the people involved.

A complete understanding of a client’s or family’s world would involve investigation of all of these areas. For purposes of assessment and intervention planning, however, not all of these dimensions will be of equal importance to every person. Some dimensions will be more important for some clients and families than others. For Sarah, the many people (children, ill husband, husband’s ill mother) depending on her was a critical dimension that affected her ability to function well. For Jay, the activities in which he wished to participate and his goals to contribute to AIDS education were important dimensions that influenced his realization that he needed to be able to hear. And for Dora, Paul’s mother, events such as family celebrations were problematic, reminding her that her child was different and stressing her as she tried to manage Paul’s behaviors in overstimulating environments.

Related posts:

- business development intern interview questions

- execution interview questions

- department of health interview questions

- interview questions to determine arrogance

- dataweave interview questions

- sales role play interview questions and answers

- Amazon excel interview questions

- interview questions for sales leaders

Related Posts

The top 20 xhtml interview questions for web developers in 2023, preparing for a udacity interview: commonly asked questions and how to answer them, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Ethnographic Interview

I’m about as far away from an ethnographer as you can get. I live in the heart of the United States and in the same home for over 20 years. And yet, I use ethnographic interviewing in one form or another every single week. How can it be that I’m not embedding myself into new and strange cultures, and yet I value skills that resemble those needed by an ethnographer so deeply? The answer lies in the techniques and thinking that The Ethnographic Interview teaches and in my work world.

I came to The Ethnographic Interview by way of Peter Morville’s work, Intertwingled . He recommended it as a way to understand information architectures – and corporate cultures – more completely. I agree. All too often, the issues we have in understanding one another are about how our cultures differ, and no one has bothered to understand the unwritten meanings behind the words we use.

Requirements Gathering

Before I share some of James Spradley’s insights into ethnography, it’s important for me to cement the connection between what people do today and what ethnography is, so that it’s criticality can be fully understood. In IT, business analysts – by role or by title – seek to understand the foreign world of the business. They learn about logistics, manufacturing, marketing, accounting, and more in an effort to translate the needs of these groups for the developers and systems designers that will create IT systems to support them.

Even the experienced business analyst who knows the company and the department well must do their best to remove all of their assumptions and start fresh in understanding what the group is doing and what they need. While it’s technically impossible to remove all assumptions, because they are so good at hiding, the ethnographer’s task is to eliminate as many as possible and to test those that remain.

I wrote a course for Pluralsight some years ago, titled “Gathering Good Requirements for Developers,” where I teach a set of techniques designed to expose assumptions, test them, and make things feel more real and understandable on both sides.

The requirements gathering process, whether a part of agile design or traditional waterfall methodologies, is absolutely essential to being able to deliver what the business needs. The process of requirements gathering is ultimately a process of eliciting and understanding what the foreign culture is saying – even if that foreign culture is inside of your organization.

What is Ethnography?

An anthropologist is expected to be off in a foreign land eating strange food and spending most of their time wondering what people are saying and what the heck they’re doing so far from those they love. Ethnography is their principle work, which is the systematic study of the culture they’ve embedded themselves in. Put differently, the goal of ethnography is (according to Bronislaw Malinowski) “to grasp the native’s point of view, his relation to life, to realize his vision of his world.”

Simply stated, it’s learning from people. However, there are several nuances. First, ethnographers invite natives to teach them. They don’t assume that they know or can learn the culture without help. Second, there are components of the culture that aren’t ever directly expressed. For instance, in the United States, the phrase “How are you?” is typically a greeting. The typical response is “I’m doing well, and you?” It doesn’t convey a real interest in the other person – until and unless it’s followed with, “I mean, really, how are you?”

If there’s one thing I’ve found that is a problem with requirements gathering, information architecture, or just working with other people, it is that we don’t truly understand. We believe we understand. We might be using the same words, but we just aren’t 100% in alignment. That’s where training in ethnography is really helpful.

Ethnographers observe behavior but inquire about the meaning. They understand objects but seek to discover the meanings that the culture assigns to these objects. They record emotions but go beyond to discover the meaning of fear, anxiety, anger, and other feelings.

In short, they dig deeper. They verify their understanding to ensure that what they believe they understand is actually right. Consider for a moment death. It’s the punctuation mark at the end of life – every life. Yet, different cultures view death differently. Some cultures keep death hidden – as is the Western point of view – while others embrace or celebrate it. Some cultures believe in reincarnation and others in an afterlife. It’s the same event, but it’s culturally very, very different.

Gary Klein explains in Sources of Power that we all make models in our head, and it’s these models that drive our thinking. He also shares how painful it can be to get these models to surface. The models are tacit knowledge that cannot be expressed in explicit language. In fact, Lost Knowledge differentiates between tacit knowledge and what’s called “deep tacit knowledge,” which are mental models and cultural artifacts of thinking that are so ingrained the person literally can’t see them.

The person the ethnographer is talking to, the informant, needs prompted to access the information they don’t know they know. A good ethnographer can tease out tacit knowledge from even the worst informants – but finding the right informants certainly makes it easier.

Indispensable Informants

If you follow agile development practices, you may notice that agile depends on a product owner who is intimately familiar with the business process that the software is being developed for. Lean Six Sigma speaks of getting to the gemba (Japanese for “the real place”) to really know what’s happening instead of just guessing. Sometimes this is also used to speak of the people who really know what’s going on. They do the real work.

The same concept applies to ethnographic research. You need someone who is encultured, really a part of what you’re studying. While the manager who once did the job that you’re looking to understand might be helpful, you’ll ideally get to the person who actually is still doing the work. The manager will – at some level, at least – have decided that they’re no longer a part of that group, and, because of that, they’ll lose some of their tacit knowledge about how things are done – and it will be changing underneath their knowledge anyway.

Obviously, your informant needs to not just be involved with the process currently, but they also need to have enough time. If you can’t get their time to allow them to teach you, you won’t learn much. Another key is that the person not be too analytical. As we’ll discuss shortly, it’s important that the informant be able to remain in their role of an encultured participant using their natural language rather than be performing translation for the ethnographer – as they’ll tend to do if they’re too analytical.

You can’t use even the best interviewing techniques in the world to extract information that no longer exists.

The heart of ethnography isn’t writing the report. The heart of ethnography is the interviewing and discovery process. It’s more than just asking questions. It’s about how to develop a relationship and rapport that is helpful. The Heart and Soul of Change speaks of therapeutic alliance and how that is one of the best predictors of therapeutic success.

Tools like those described in Motivational Interviewing can be leveraged to help build rapport. Obviously, motivational interviewing is designed to motivate the other person. However, the process starts with engaging, including good tips to avoid judgement and other harmful statements that may make a productive relationship impossible.

For his part, Spradley in The Ethnographic Interview identifies the need for respect or rapport and provides a set of questions and a set of interviewing approaches that can lead to success.

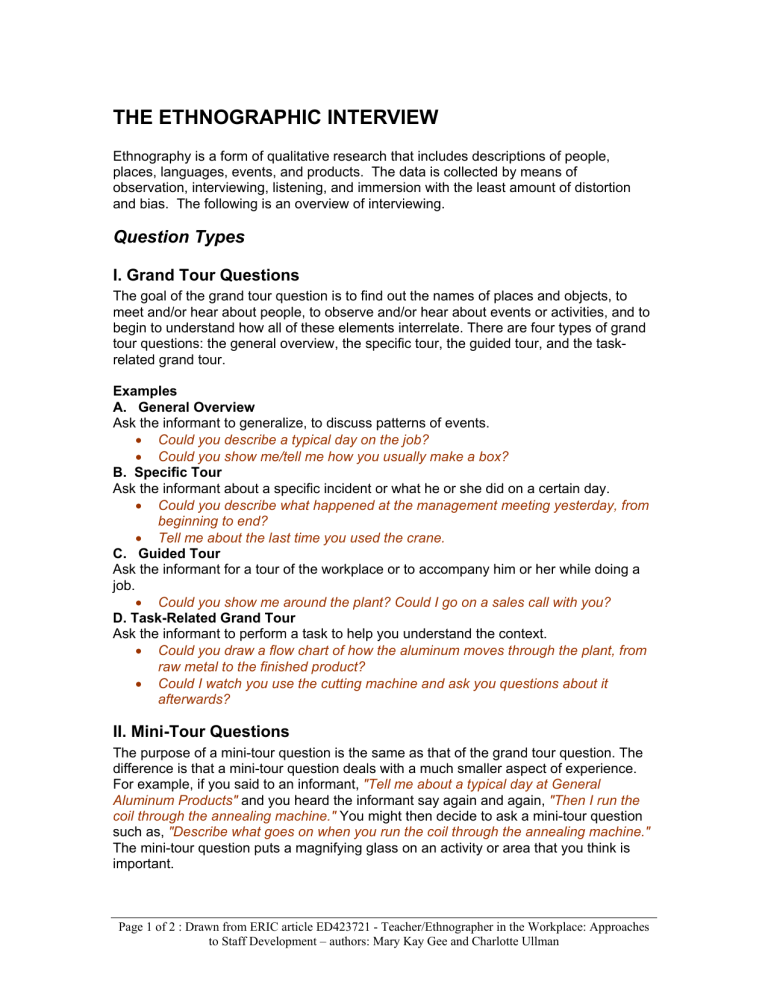

Types of Questions

At a high level, ethnographic questions fall into three broad categories – descriptive, structural, and contrast questions. These questions allow the ethnographer to dip their toes into the water of understanding, structure their understanding, and understand terms with precision.

Descriptive Questions

Descriptive questions are by far the most voluminous questions that will be asked. They form the foundation of understanding what is in the informant’s world and how they use the objects in their world. Descriptive questions fall into the following categories:

- Typical Grand Tour Questions – Asking for a typical situation in their environment

- Specific Grand Tour Questions – Asking for a specific time and what happened

- Guided Grand Tour Questions – Asking to see the specific things happening in an area of the informant’s environment

- Task-Related Grand Tour Questions – Asking the informant to explain a specific task that they do and how they do it

- Typical Mini-Tour Questions

- Specific Mini-Tour Questions

- Guided Mini-Tour Questions

- Task-Related Mini-Tour Questions

- Example Questions – Asking for a specific example of something that the informant has answered in general

- Experience Questions – Asking for experiences that the informant might have found interesting, relevant, or noteworthy

- Direct Language Questions – Asking what language they use to refer to something in their environment

- Hypothetical-Interaction Questions – Asking questions about hypothetical situations that the ethnographer creates

- Typical-Sentence Questions – Asking what kind of sentences that would be used with a phrase

Descriptive questions allow ethnographers to amass a large amount of information, but that information is unstructured and unconnected. While it’s necessary to spend some time in this space, after a while, it will become necessary to seek to understand how the informant organizes this information.

Structural Questions

As important as building a vocabulary is, understanding the relationships between various terms is more illuminating to the structural processes that the informant uses to organize their world. We use symbols to represent things, and these symbols can be categories that contain other symbols. This is a traditional hierarchical taxonomy like one might find when doing an information architecture (see Organising Knowledge , How to Make Sense of Any Mess , and The Accidental Taxonomist ).

In truth, there are many different kinds of ways that symbols can be grouped into categories, and understanding this structure is what makes the understanding of a culture rich. Spradley proposes that there are a set of common semantic relationships that seem to occur over and over again:

Spradley proposes five kinds of structural questions designed to expose the semantic relationships of terms:

- Domain Verification Questions – Asking whether there are different kinds of a term that the informant has shared

- Included Term Verification Questions – Asking whether a term is in a relationship with another term

- Semantic Relationship Verification Questions – Asking whether there is a kind of term that relates other terms or if two terms would fit together in a sentence or relationship

- Native-Language Verification Questions – Asking whether the words spoken from the informant to the ethnographer are the words that would be used when speaking to a colleague

- Cover Term Questions – Asking if there are different types of a particular term

- Included Term Questions – Asking if a term or set of terms belong to another term

- Substitution Frame Questions – Asking if there are any alternative terms that could be used in the sentence that an informant has spoken

- Card Sorting Structural Questions – Asking informants to organize terms written on cards into categories and by relatedness. This is similar to an information architecture card sorting exercise. (See my post and video about Card Sorting for more.)

Descriptive questions will be interspersed with structural questions to prevent monotony and to allow the ethnographer to fill in gaps in their knowledge. Though structural questions help provide a framework to how terms relate, the relationship strength between terms isn’t always transparent. That’s why contrast questions are used to refine the understanding of what the strength of the relationship is between terms.

Contrast Questions

Sometimes you can’t see differences in the abstract. For instance, our brains automatically adapt to changing light and convert something that may look blueish or pinkish to white, because we know something (like paper) should be white, even when the current lighting makes it look abnormally blue or pink. So, too, can the hidden differences between terms be obscured until you put them right next to each other. That’s what contrast questions do. They put different terms side-by-side, so they can be easily compared.

The kinds of contrast questions are:

- Contrast Verification Questions – Asking to confirm or disconfirm a difference in terms

- Directed Contrast Questions – Asking about a known characteristic of a term and how other terms might contrast on that characteristic

- Dyadic Contrast Questions – Asking the informant to identify the differences between two terms

- Triadic Contrast Questions – Asking the informant to identify which one of three terms is least like the other two

- Contrast Set Sorting Questions – Asking the informant to contrast an entire set of terms at the same time

- Twenty Questions Game – The ethnographer selects a term from a set and the informant asks a set of yes/no questions of the ethnographer until they discover the term. This highlights the hidden ways that informants distinguish terms. (This is similar to techniques like Innovation Games , where the games are designed to reveal hidden meanings.)

- Rating Questions – Asking questions about the relative values placed on different terms – along dimensions like easiest/most difficult and least/most interesting, least/most desirable, etc.

The sheer number of types of questions can seem overwhelming at first. However, many of these forms flow automatically if you develop a genuine interest in the informant and their culture. Still, sometimes it’s hard to try to learn a new language and think about what’s the next question that you need to ask to keep the conversation moving.

Multiple Languages

In the case of an anthropologist who is working with a brand new culture, it could be that they’re learning a whole new language – literally. However, in most cases, it’s not that the language is completely different and new to the ethnographer. In most cases, it’s the use of the terms that are different. Just experiencing the difference between UK English and American English can leave someone a bit confused. A rubber in England is an eraser in the US, and a cigarette in the US is a fag in the UK. While both are English, the meaning and expectations of the word are quite different.

We often forget how we speak differently in a profession. A lexicon – special language – develops around industries that aren’t a part of the general consciousness. It’s the ethnographer’s job to discover not only that lexicon but also what the words mean to the rest of us.

Who Should Translate, and When?

When there are multiple languages, there is always the need to translate from one language to another. However, who does that translation – and when is the translation done? Informants, in their desire to be helpful, are likely to try to translate the information of their culture into terms that the ethnographer will understand. While the intent is helpful, the result is that the ethnographer doesn’t get to understand that aspect of the culture.

So, while translation is necessary, it’s best to continue to discourage the informant from being the one who is doing the translation. The ethnographer can leave their notes in native language and then translate later. This also allows them to validate information with structural and contrast questions. Sometimes, it’s this review that reveals some underlying themes of the culture.

In most cultures, there’s a set of recurring themes that appear. It isn’t explicit or stated, but there are those sacred cows that everyone worships that shapes the way the organization thinks. An entrepreneurial company has agility or velocity at the heart of the way that they organize their thoughts. A brand-focused company may be inherently focused on status or image. While these values aren’t typically articulated, they’re assumed, and they shape the way that the organization thinks – about everything.

By having the opportunity to review and rework translations, these themes begin to emerge. The semantic relationships appear over and over again until it becomes apparent that they’re not specific ways of organizing a topic but are instead a way of organizing everything.

One of the challenges that I often see in requirements is that the business analyst doesn’t always spend the time drilling into the details and verifying understanding in a way that results in requirements that fully express the needs of the business and how they do work. The ethnographic process – including the variety of questions – is one way to combat this challenge. It’s possible to leverage the ethnographic process to more deeply understand what is happening and how the systems are expected to help.

While I may be far from the fields of a foreign land, speaking to people whose language I don’t speak, I often move from industry to industry and company to company, learning their languages and the way that they think about the world. The Ethnographic Interview is, therefore, a useful tool for helping me get a better understanding and better requirements.

- No category

EthInterview

Related documents

Add this document to collection(s)

You can add this document to your study collection(s)

Add this document to saved

You can add this document to your saved list

Suggest us how to improve StudyLib

(For complaints, use another form )

Input it if you want to receive answer

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

- MEDICAL ASSISSTANT

- Abdominal Key

- Anesthesia Key

- Basicmedical Key

- Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology

- Musculoskeletal Key

- Obstetric, Gynecology and Pediatric

- Oncology & Hematology

- Plastic Surgery & Dermatology

- Clinical Dentistry

- Radiology Key

- Thoracic Key

- Veterinary Medicine

- Gold Membership

Interviewing

Interviews as sources of data In the last two decades, interviews have become the most common form of data collection in qualitative research. Novice health researchers often rely on interviews as their main form of data collection because they want to gain the inside view of a phenomenon or problem but also find observation difficult. It is easily understandable why health professionals wish to interview clients and colleagues. In their professional lives, too, they have conversations with patients in order to obtain information. They counsel their clients and already possess many interviewing skills. Nursing or midwifery assessment, for instance, relies on skilful questions and includes interviewing to elicit information from patients or clients. It might therefore be assumed that research interviews are easy to carry out, but interviewing is a complex process and not as simple as it seems. Beatrice and Sidney Webb who undertook social research around the turn of the last century used the term ‘conversation with a purpose’ when discussing interviews, and Rubin and Rubin (2005) too believe that researcher and informant become ‘conversational partners’, but the interview has only some of the characteristics of a conversation. Research interviews differ from ordinary conversations because the rules of the interview process are more clearly defined. The one-to-one interview consisting of questions and answers is the most common form of research interview. Other types include focus group and narrative interviews (discussed more fully in Chapters 8 and 12). Interview studies have contributed to the understanding of participants and of the wider culture. In health research, interviewing provides the basis both for exploring colleagues’ perspectives and clients’ interpretations. It is necessary, however, to warn researchers of ‘anecdotalism’ when they accept ‘atrocity stories’ from participants and do not always explore cases which contradict these (Silverman, 2006). If researchers apply high standards and rigour to the research, and search for contrary occurrences in the analysis of the interview data, their studies will represent – at least to some extent – the reality of most of the participants’ perceptions and a description of the phenomenon under study. The interview process Unlike everyday conversations, research interviews are set up by the interviewer to elicit information from participants. The purpose of the interview is the discovery of informants’ feelings, perceptions and thoughts. Marshall and Rossman (2006) maintain that interviews focus on the past, present and, in particular, the essential experience of participants. The interview can be formal or informal; often informal conversations or chats with participants also generate important ideas for the project. Depending on the response of participants, researchers formulate questions as the interview proceeds rather than asking pre-planned questions. This means that each interview differs from the next in sequence and wording, although distinct patterns common to all interviews in a specific study often emerge in the analysis. Indeed, for many research approaches it is necessary that researchers discover these patterns when analysing data. One interview, however, does not always suffice. In qualitative inquiry it is possible to re-examine the issues in the light of emerging ideas and interview for a second or third time. Seidman (2006) sees three interviews as the optimum number, but these require much planning in the short time span available to undergraduates for their project, so this is only possible for postgraduates. Many novice researchers therefore use one-off interviews although postgraduates and other more experienced researchers sometimes carry out more than one with each participant. Pilot studies are not always used in qualitative inquiry as the research is developmental, but novice researchers could try interviews with their friends and acquaintances to get used to this type of data collection. We found that we lacked confidence when we started, and a practice run proved very useful. In our experience students become more confident as interviews proceed. Most qualitative research starts with relatively unstructured interviews in which researchers give minimal guidance to the participants. The outcome of initial interviews guides later stages of interviewing. As interviews proceed, they become more focused on the particular issues important to the participants and which emerge throughout the data collection. Most qualitative studies do not only explore commonalities and uncover patterns, but they also describe the unique experiences of individuals particularly in one-to-one interviews. One-to-one interviews are the most common form of data collection although researchers also use group interviews (see Chapter 8). Types of interview Researchers have to decide on the structure in the interview. There is a range of interview types on a continuum, from the unstructured to the structured. Qualitative researchers generally employ the unstructured or semi-structured interview. The unstructured, non-standardised interview Unstructured interviews start with a general question in the broad area of study. Even unstructured interviews are usually accompanied by an aide mémoire , an agenda or a list of topics that will be covered. There are, however, no predetermined questions except at the very beginning of the interview. Example Tell me about your experience at the time you found out about your… Aide mémoire Feelings in the doctor’s surgery Interaction with different types of professionals Coping with the condition and the associated pain Being treated Social support from other patients, relatives and friends Practical support etc. (these are merely examples) This type of unstructured interviewing allows flexibility and makes it possible for researchers to follow the interests and thoughts of the informants rather than follow their own assumptions. Interviewers freely ask questions from informants in any order or sequence depending on the responses to earlier questions. Warm-up and simple questions are generally asked first; however, if the interviewer leaves the essential questions till the end of the interview the participant may be tired and reluctant to discuss deeper issues. Researchers also have their own agenda. To achieve the research aim, they keep in mind the particular issues which they wish to explore. However, direction and control of the interview by the researcher is minimal. Generally, the outcomes of these interviews differ for each informant, though usually certain patterns can be discerned. Informants are free to answer at length, and great depth and detail can be obtained. The unstructured interview generates the richest data, but it also has the highest ‘dross rate’ (the amount of material of no particular use for the researcher’s study), particularly when the interviewer is inexperienced. The semi-structured interview Semi-structured or focused interviews are often used in qualitative research. The questions are contained in an interview guide (not interview schedule as in quantitative research) with a focus on the issues or topic areas to be covered and the lines of inquiry to be followed. The sequencing of questions is not the same for every participant as it depends on the process of the interview and the responses of each individual. The interview guide, however, ensures that the researcher collects similar types of data from all informants. In this way, the interviewer can save time, and the dross rate is lower than in unstructured interviews. Researchers can develop questions and decide for themselves what issues to pursue. Example Tell me about the time when your condition was first diagnosed. (Depending on the language use and understanding of the participant, this has to be phrased differently. For instance: What did you think when the doctor first told you about your illness?) What did you feel at that stage? Tell me about your treatment. What did the doctor or nurses say? What happened after that? How did your husband (wife, children) react? What happened at work? and so on. The interview guide can be quite long and detailed although it need not – should not – be followed strictly so that the participant has some control. It focuses on particular aspects of the subject area to be examined, but it can be revised after several interviews because of the ideas that arise. Although interviewers aim to gain the informants’ perspectives, the former need to keep some control of the interview so that the purpose of the study can be achieved and the research topic explored. Ultimately, the researchers themselves must decide what interview techniques or types might be best for them and the interview participants. Our students and other researchers preferred good questions of medium length combined with the use of prompts and reported better results. The structured or standardised interview Qualitative researchers in general do not use standardised interviews as they are contradictory to the aims of qualitative research. In these, the interview schedule contains a number of pre-planned questions. Each informant in a research study is asked the same questions in the same order. This type of interview resembles a written survey questionnaire. Standardised interviews save time and limit the interviewer effect. The analysis of the data seems easier as answers can be found quickly. Generally, knowledge of statistics is important and useful for the analysis of this type of interview. However, this type of pre-planned interview directs the informants’ responses and is therefore inappropriate in qualitative approaches. Structured interviews may contain open questions, but even then they cannot be called qualitative. Qualitative researchers use structured questions only to elicit socio-demographic data, i.e. about age, duration of condition, duration of experience, type of occupation, qualifications, etc. Sometimes research or ethics committees ask for a predetermined interview schedule so that they can find out the exact path of the research. For the purpose of gaining permission, a semi-structured interview guide is occasionally advisable for health researchers. Types of questions in qualitative interviews When asking questions, interviewers use a variety of techniques. Patton (2002) lists particular types of questions, for example experience , feeling and knowledge questions. Examples Experience questions Could you tell me about your experience of caring for patients with arthritis? Tell me about your experience of epilepsy. Feeling questions How did you feel when the first patient in your care died? What did you feel when the doctor told you that you suffer from… Knowledge questions What services are available for this group of patients? How do you cope with this condition? Spradley (1979) distinguishes between grand-tour and mini-tour questions. Grand-tour questions are broader, while mini-tour questions are more specific. Examples Grand-tour questions Can you describe a typical day in the community? (To a community midwife) Tell me about your condition. (To a patient) Mini-tour questions Can you describe what happens when a colleague questions your decision? (To a nurse) What were your expectations of the pain clinic? (To a patient) The sequencing of questions is also important. Practical considerations In qualitative studies questions are as non-directive as possible but still guide towards the topics of interest to the researcher. Researchers should phrase questions clearly and aim at the various participants’ levels of understanding. Ambiguous questions lead to ambiguous answers. Double questions are best avoided; for instance it would be inappropriate to ask: How many colleagues do you have, and what are their ideas about this? The researcher must be aware of practical difficulties in the data collection phase, particularly when interviewing in hospital. The routine of the hospital is disrupted by the presence of the nurse or midwife researcher whose activities might be viewed with suspicion by colleagues. A quiet place for interviews cannot always be found, and therefore the privacy of patients may be threatened. The ward might be full of noise and activity, and the researcher does not always find a convenient slot for interviewing without being interrupted by nursing activity, consultant round, cleaners, meals and so on. In the community, interviews are often interrupted by children or spouses and by the visits of friends or relatives. Probing, prompting and summarising During the interviews researchers can use prompts or probing questions. These help to reduce anxiety for researcher and research informant. The purpose of probes is a search for elaboration, meaning or reasons. Seidman (2006) suggests the term ‘explore’ and dislikes the word ‘probe’ as it sounds like an interrogation, and is the name for a surgical instrument used in medical or dental investigations and stresses the interviewer’s position of power. Exploratory questions might be, for instance: What was that experience like for you? How did you feel about that? Can you tell me more about that? That’s interesting, why did you do that? Questions can follow up on certain points that participants make or words they use. The researcher could also summarise the last statements of the participant and encourage more talk through this technique. Example You told me earlier that you were very happy with the care you received in hospital. Could you tell me a bit more about that? Participants often become fluent talkers when asked to tell a story, reconstructing their experiences, for instance a day, an incident, the feeling about an illness. Unfortunately the data from interviews are sometimes more fluent or extensive when the participants are articulate, and occasionally researchers may choose those who have language and interaction skills. This may create bias in the interviews however and is not a good strategy. Example A number of years ago one of our PhD candidates – an experienced midwife with good verbal and interactive skills – intended to interview clients about the nil-by-mouth policy of the maternity ward in which she wished to carry out research for her research diploma. She found that certain individuals only answered in very short sentences, could not be prompted and were generally in awe of the situation and the researcher. Also the policy was not an issue of interest to them – their concern focused only on the birth of their baby – but only for the midwives involved. The researcher had to abandon the topic area because she had not enough material for a long research study and also felt that there would be bias against less articulate and less confident clients. The social and language skills of the researcher often make a difference to the outcome of the interview. Non-verbal prompts are also useful. The stance of the researcher, eye contact or leaning forward encourages reflection. In fact, listening skills, which some nurses and midwives already possess from the counselling of patients, will elicit further ideas. Patients often give monosyllabic answers until they have become used to the interviewer, because they are reluctant to uncover their feelings or fear that judgements might be made about them. When participants do not understand the interview question, the researcher can rephrase them in the language they understand. The social context of the interview Interviews must be seen in the social context in which they occur; this affects the relationship between researcher and research as well as the data generated by it (Manderson et al., 2006). The setting is of particular importance; if interviews take place in the home of the participants, they are more relaxed, the researcher might gain richer data and the participant is in some position of control. On the other hand, this setting can be a difficult choice for the researcher as there might be many distractions such as children or spouses who interrupt the proceedings. Sometimes a neutral place such as a corner in a café or park, or an academic environment can be appropriate. The researcher has to reflect on time and location and the persons involved in the interaction. Experience, background and characteristics of the researcher, as well as the participants’ group membership such as age, gender, class or ethnic group might also influence the interaction. Manderson et al. (2006) suggest that changes in any of these factors might generate different interview data as the social dynamics of the interview vary; indeed Roulston et al. (2003: 654) stress ‘the socially constructed nature of interview talk’. When sensitive topics are discussed, researchers have to use their own judgement whether their gender or ethnic membership might interfere with the research relationship. In some situations it is more sensitive and even useful when researcher and participant are of similar background. This is by no means always so. One of our students, a very young woman, interviewed older people about their lives. This study elicited more data than would be usual. The participants provided very rich data and deep thoughts – perhaps because they did not feel threatened. When patients are interviewed, they might ask the researcher about advice on their condition or treatment. It is best to separate the researcher and professional roles, although this cannot always be done. It is best to point out a professional source of information or put the participants in touch with an expert who can answer their questions. In the case of very vulnerable people and sensitive topics, the researcher might seek advisors or experts before the research starts and ask for permission to contact them if necessary. If an emergency occurs during the interview, the researcher has to adopt the best way to assist the patient. Unexpected outcomes: qualitative interviewing and therapy Certain commonalities exist between qualitative and therapeutic interviews. However, researchers and therapists have different aims; the researcher’s aim is to gain knowledge while the therapist’s aim is to assist in the healing process. Several studies have shown, however, that qualitative interviews might be beneficial for the participants, especially after they have gone through a traumatic experience (for instance, Colbourne and Sque, 2005 among others). Kvale (1996) argues that among other elements of interviews, interaction with others and remembering the past might be therapeutic. Example Colbourne and Sque (2005) report on research that included qualitative interviews with cancer patients. The outcome of these interviews showed them to have a beneficial effect on some of the participants. They suggest that nurse researchers as listeners could help participants gain more self-awareness and express repressed emotions among other factors. Just talking and interacting with others can be helpful. The research aim did not change through the process of the study, and the therapeutic impact was an unexpected – if welcome – outcome.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

- The Paradigm Debate: The Place of Qualitative Research

- Ethnography

- Mixed Methods: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Research

- Data Analysis: Procedures, Practices and Computers

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Comments are closed for this page.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

- Remember me Not recommended on shared computers

Forgot your password?

Mini-Tour Question

By Outdors21 June 3, 2017 in Tour Talk

- Reply to this topic

- Start new topic

Recommended Posts

My friend and I were having an argument during our round today (I shot 69! my best in a few years).

Would a scratch/0 have ANY success on a mini tour over 20 events? a +1?

What's the cut off.

Link to comment

Share on other sites.

- Created 7 yr

- Last Reply 3 yr

Top Posters In This Topic

Popular Days

Santiago Golf 5 posts

EntourageLife 5 posts

HighSpeedScene 4 posts

Outdors21 3 posts

Jun 11 2017

Jun 12 2017

The short answer is no.

A 0/+1 is not really even capable of winning AJGA/junior golf level tournaments these days. They have essentially zero chance of cashing any kind of check at any reputable mini tour. Since handicap is pretty worthless as it relates to competitive tournament ability, it's hard to even give a specific number that has a chance of being competitive.

https://www.gstour.c...urnamentID=6279

Here's a recent event where shooting -7 on a 74.4 rated course over three days netted a whopping $30 on the entry fee.

Someone who finished in 16th place shot differentials of .6, -5.4, and -7.4 and made -$720.

ScratchyDawg

20 years ago, a scratch golfer could probably make a meager living on the mini tours. Nowadays, he'd be lucky to win his club championship.

golfandfishing

Over 20 events - a scratch has no chance. The best chance would be a one day event posting a career round. The more rounds you play the more a scratch will deviate to his average score of 75 or so. That will get you run over, although you will be very popular with the rest of the field.

That is precisely what I said. He disagreed. When I was a scratch/+1, I played a few rounds with a legitimate +4 and the difference was astonishing. It was very humbling.

The difference between my scratch friend and my +4-5 friend is that my scratch friend occasionally breaks par with like a 69-70 while I have seen my +4-5 friend shoot low sixties on several occasions.

golfing_penguin

I´d have to say no joy as well because the 0/+1 isn´t likely to have the ability to shoot a 61 on a 6500 yard course, which is (grossly simplified) what mini-tour guys can do. On the flip side, boring golf and nearly always shooting -3 would fair reasonably, especially over the 61-75 guy

Thrillhouse

Nope. I calculated the tournament handicaps of some mini tour players on here a few years ago to attempt to settle this debate.

A tournament +4 made less than half the cuts over the course of the year and lost money. I think the break even point was around a tournament +6.5, and the guy who led the money list was a +9.

A scratch would never sniff a cut and have a scoring average around 78 or so assuming the courses they played were rated around 74.

Nope. I calculated the tournament handicaps of some mini tour players on here a few years ago to attempt to settle this debate. A tournament +4 made less than half the cuts over the course of the year and lost money. I think the break even point was around a tournament +6.5, and the guy who led the money list was a +9. A scratch would never sniff a cut and have a scoring average around 78 or so assuming the courses they played were rated around 74.

Sweet lord in heaven.

lumberman2462

I used to play in a few Florida mini-Tour pro-ams every year and was amazed at how good some of those guys were and couldn't advance to the even the Web.com. A few did make it: Boo Weekley, Bubba Watson were the biggest names that made it to the Tour and several others made it to Web.com.

Thrillhouse statement about a scratch shooting 78 is pretty close. At times i was bouncing around 1-5 handicap and over those the three days of a tournament I'd shoot 75 and then 80 all the while playing along some kid that would shoot 65 one day and 73 the next.

I can't count how many times our "Pro" for the week was fresh out of college and chasing the dream - only enough money to spend 6 weeks or a few months seeing if they had the game to play. That's not a criticism just an observation.

But it has been fun over the years to flip on TGC and see a name pop up and remember playing with them. I always played with a friend in these events and he'll call me and say "You remember that kid that hit his tee shot into the swimming pool?" Or " remember when that guy freaked out and broke a bunch of club?" -Turn it on he's on the leader board on the Web.com.

SYard T388 TaylorMade RBZ 13-15 Miura CB-57 3-PW Miura 51Y, 52K,56K, 57C, 60K Old Titleist Blade

Not a chance. Have to be a +3 or 4 to make the cut or qualify for state opens most of the time. Now if you want to talk about making money that's a different story.

Lagavulin62

This is turning out to be a pretty depressing thread. Instead of dreaming golf, I wonder if I had devoted more time to the weights and stuck with football, would I have had a snowballs chance of making the Longhorns scout team?

HighSpeedScene

I was +4 when I tried to make enough gas money to get from Brandon to Orlando, and I freaking STARVED. I figured I needed at least two more index points to even compete.

A guy named Pete Jordan (had been on/off the tour) shot 63 in a little one-dayer that should have been 55 if he could have putted - I kept his card that day. I asked him if after the round if I had ANY shot and he didn't even hesitate: No.

That night I finished my law school applications.

I know better than to read a thread that starts with "My friend and I" ?

I am literally surrounded by scratch golfers; legit, plus-handicap amateurs; mini-tour players; web.com guys: and legit PGA Tour players.

The difference from level-to-level is subtle, but real. And it can be quantified, but really only by long-term tournament scoring average over ALL rounds (not best 10 of last 20 like an index is calculated) compared to course rating/slope

I will give you a perfect example: when I was a bit younger I qualified for the only professional event I ever attempted: The California State Open. At the time I was about a +2. I missed the cut. I played very poorly, but I missed the cut.

Could I have made the cut? Which was, if I remember correctly, three over? Absolutely I could have made the cut. If I played a bunch of tournaments I could've made a couple cuts. Could I have made anything even remotely approaching a living? Absolutely not. I couldn't even have paid my expenses. It would've been a losing proposition from the get go.

I was simply never quite good enough to make even my expenses back as a pro.

Not long or consistent enough off the tee, a bit on the nervous side under pressure, and I will generally hit one or two really bad shots a round.

Any legitimate plus handicap golfer has a (small) chance to make an occasional cut on pretty much any mini tour, but that is it. They would never, ever contend to win, and they would be lucky to make a couple hundred dollars if they ever managed to k a cut. There are just far, far too many +4 to +6 index guys out there today....

PING G400 Max - Atmos Tour Spec Red - 65s Titleist TSi2 16.5* 4w - Tensei Blue - 65s

Titleist TSi2 3H (18*), 4H (21*) - Tensei Blue 65s Adams Idea Tech V4 5H, 6H, 7H ProLaunch Blue 75 HY x-stiff Titleist AP2 716 8i 37* KBS Tour S; Titleist AP2 716 9i 42* KBS Tour S Cleveland RTX-4 mid-bounce 46* DG s400 Cleveland RTX-4 mid-bounce 50* DG s400 Cleveland RTX-4 full-sole 56* DG s400 Cleveland RTX-4 low-bounce 60* DG s400 PING Sigma 2 Valor 400 Counter-Balanced, 38"

Heh - sounds like scratch is the new 4 hcp nowadays.

Edit: that said, I know the difference between me and a legit scratch is significant. Players who can make some money professionally might as well be playing a different game since they're so much better.

EntourageLife

Give it up. The average scratch golfer from Michigan or "up North", or anywhere has ZERO comprehension of how good a tour player actually is...

Santiago Golf

I think most low handicappers have a shot at qualifying for there State Open or Am, you got think a couple over or even makes it and they could out there shoot a great round for themselves. A player in Michigan Am came in 2nd in the stroke play keeps a cap of around scratch to +1.

I think a scratch could career it for two days and make a cut on a mini tour, but probably couldn't make a living out there.

What do you have against the greatest state in Golf.

Pro Caddie & I teach golf

Driver: PXG 9* ; HZDRUS Handcrafted 63 6.0

Long Game: PXG 13*, PXG 16*; HZDRUS Handcrafted 83 6.5 (flip between the two)

Driving Iron: PXG 0311 4 iron bent 17.5*; ProForce VTS 100HX

Hybrid: PXG Gen 1 19*; HZDRUS Handcrafted 100 6.5

Irons: NIKE CB 4-PW Raw finish ; Aldila RIP Tour SLT 115 Tour Stiff (.25 inch gapping)

Wedges: Titleist SM9 50*, 54*; True Temper DG S300 (36 inches)

L-Wedge: Custom 60*; KBS Tour Stiff (36 inches)

Putter: Scotty Cameron Studio Design #5 35 inches: Super Stroke GP Tour

Ball: ProV1x

It is the greatest state in golf! But also, nobody living there has the understanding of just how good an actual tour player is...

Maybe because we no longer to get see the best in the world play every year in Michigan. But we still have a good understanding of how good it takes to be a tour player

I know. The Buick Open was one of my favorite events. Michigan has some of the finest, most enjoyable golf courses in the world.

Forest Dunes, amazing.

Point O' Woods, old school amazing

True North, Bay Harbor, Arcadi, The Dunes, Oakland Hills, Crystal Downs, Orchard Lake, Kingsley, U of Mich, Detroit Golf Club, GreyWalls, and the list goes on

rangersgoalie

Twenty years ago, the best maybe waked out a living.

A scratch golf was a purse builder back then too

Talk to Frank from Moonlight Tour. He'll tell you. Made him rich too...

bladehunter

South Carolina !?

Edit. Lol I don't know who is the single greatest state. But no other region will top NC SC GA in my opinion. You can't drive 40 minutes in any direction from anywhere in three states without running over a quality course. And inbetween are hundreds of good clean munis that you can play for literally under $20 if your walking.

Cobra LTD X 9* Hzrdus RDX blue

TM Sim2 max tour 16* GD ADHD 8x

Ping i530 4-Uw AWT 2.0

Mizuno T22 raw 52-56-60 s400

LAB Mezz Max armlock

Its the same in Michigan

Most guys who play think par is 68, so you shot one over. ;)

i don’t need no stinkin’ shift key

Wasn't walking outlawed? There are courses here, mostly of the private/public type, that will practically hang a man just for suggesting it.

South Carolina vs Michigan lol

Sorry SC not even close

Google Mickey Soli...not just from MI, but from the upper peninsula. Those boys up north will eat your lunch on a 2 month season...

Join the conversation

You can post now and register later. If you have an account, sign in now to post with your account.

× Pasted as rich text. Paste as plain text instead

Only 75 emoji are allowed.

× Your link has been automatically embedded. Display as a link instead

× Your previous content has been restored. Clear editor

× You cannot paste images directly. Upload or insert images from URL.

- Insert image from URL

- Submit Reply

Recently Browsing 0 members

- No registered users viewing this page.

Titleist GT drivers - 2024 the Memorial Tournament

GolfWRX_Spotted posted a topic in Tour and Pre-Release Equipment , June 3

- 255 replies

2024 Charles Schwab Challenge - Discussion and Links to Photos

GolfWRX_Spotted posted a topic in Tour and Pre-Release Equipment , May 20

2024 PGA Championship - Discussion and Links to Photos

GolfWRX_Spotted posted a topic in Tour and Pre-Release Equipment , May 13

2024 Wells Fargo Championship - Discussion and Links to Photos

GolfWRX_Spotted posted a topic in Tour and Pre-Release Equipment , May 6

2024 CJ Cup Byron Nelson - Discussion and Links to Photos

GolfWRX_Spotted posted a topic in Tour and Pre-Release Equipment , April 29

Announcements

- Spotted: Titleist GT2 Driver Photos

Popular Now

By GolfWRX_Spotted Started 1 hour ago

By JD3 Started 2 hours ago

By SNIPERBBB Started 2 hours ago

By GolfWRX_Spotted Started 2 hours ago

By MarLin Started 2 hours ago

Welcome. Register Here.

Come on in, the water is fine...

Recent B/S/T

nicelife · Started 16 minutes ago

Tyrick24 · Started 1 hour ago

TheMagicStinger · Started 1 hour ago

Turmoil35x · Started 1 hour ago

rbj69 · Started 2 hours ago

GolfWRX_Spotted · Started June 3

- Existing user? Sign In

The Bag Room

- Tour & Pre-Release Equipment

- WRX Club Techs

- Golf Sims/GPS/RFs/Apps

- Golf Style and Accessories

The Club House

- General Golf Talk

- Classic Golf And Golfers

- Courses, Memberships and Travel

- Groups, Tourneys, and Partners Matching

WRX Academy

- Instruction & Academy

- Rules of Golf and Etiquette

- Swing Videos and Comments

Classifieds & ProShops

- Deal/No Deal

Website Help

- Forum Support

- BST AD Help Forum

My Activity Streams

- BST/Deal Activity

- All Activity

- Unread - No BST/19th

- Subscriptions

Classifieds

- For Sale Forum

- Wanted to Buy

- Mall of Pro Shops

- Where Did My Ad Go?

- Trade In Tool

- Create New...

16 Tour Guide Interview Questions (With Example Answers)

It's important to prepare for an interview in order to improve your chances of getting the job. Researching questions beforehand can help you give better answers during the interview. Most interviews will include questions about your personality, qualifications, experience and how well you would fit the job. In this article, we review examples of various tour guide interview questions and sample answers to some of the most common questions.

or download as PDF

Common Tour Guide Interview Questions

What made you want to become a tour guide, what are some of your favorite places to tour, what do you think makes a great tour guide, what do you think are the benefits of touring with a guide, how do you develop your tours, what research do you do to prepare for a tour, what are some of the challenges you face as a tour guide, how do you handle difficult questions from tour participants, what are some of your favorite stories or anecdotes from your tours, what do you think sets your tours apart from others, what do you think are the most important elements of a successful tour, how do you ensure that your tours are enjoyable and informative for all participants, what are some of your tips for making the most of a tour, how do you deal with unexpected situations that come up during a tour, what are some of your favorite places to eat or drink near the tour sites, what are some of your other interests or hobbies outside of being a tour guide.

The interviewer is trying to gauge the applicant's motivation for wanting to become a tour guide. It is important to know the applicant's motivation because it can help the interviewer determine if the applicant is likely to be a good fit for the position. For example, if the applicant is interested in becoming a tour guide because they enjoy working with people and helping others learn about new places, then they are likely to be a good fit for the position. However, if the applicant is interested in becoming a tour guide because they want to make a lot of money, then they may not be as good of a fit for the position.

Example: “ I have always loved exploring new places and learning about different cultures, so becoming a tour guide was a natural fit for me. I love being able to share my knowledge and passion for travel with others, and help them create their own amazing travel experiences. ”

This question allows the interviewer to get to know the tour guide on a personal level and learn about their interests. Additionally, it helps the interviewer determine if the tour guide is knowledgeable about the area and can provide a good experience for tourists.

Example: “ There are so many amazing places to tour, it's hard to choose just a few! Some of my personal favorites include ancient archaeological sites, like the pyramids of Giza or Machu Picchu. I also love touring natural wonders, like the Grand Canyon or Niagara Falls. And of course, I always enjoy touring cities with rich history and culture, like Rome or Paris. No matter where you go, there's always something new and exciting to see! ”

There are many qualities that make a great tour guide, and what the interviewer is looking for is to see if the candidate has the qualities that are most important for the job. Some of the qualities that might be important include: being able to effectively communicate with people from all backgrounds, being organized and able to keep track of many different details, being able to think on your feet and solve problems quickly, and having a deep knowledge of the area that you are touring.

Example: “ A great tour guide is someone who is knowledgeable about the area they are touring, and can provide interesting and engaging commentary to keep people entertained. They should also be able to handle any questions or concerns that people have, and be able to keep the group on schedule. ”

The interviewer is asking this question to gain insight into the Tour Guide's understanding of the benefits of touring with a guide. It is important to know the benefits of touring with a guide because it can help the interviewer determine if the Tour Guide is knowledgeable about their job and if they are able to provide a good experience for tourists.

Example: “ There are many benefits to touring with a guide. First, they can provide you with insider information and tips about the destination that you may not be able to find in a travel book or online. Second, they can help you avoid tourist traps and show you the best places to eat, shop, and sightsee. Third, they can help you connect with the local culture by introducing you to locals and providing insights into the history and customs of the area. Finally, having a guide can simply make your trip more enjoyable by taking care of the logistics and planning so that you can relax and enjoy your vacation. ”

The interviewer is asking how the tour guide develops their tours because they want to know how much effort the tour guide puts into making each tour interesting and enjoyable for the guests. It is important for the tour guide to be able to develop their tours because it shows that they are willing to put in the extra work to make sure that their guests have a great experience.

Example: “ There are many ways to develop tours. One way is to research the area you will be touring and create an itinerary based on your findings. Another way is to speak with locals and get their recommendations on what to see and do. You can also use online resources, such as travel websites and blogs, to get ideas for your tour. Once you have an idea of what you would like to include on your tour, you can start creating your route and mapping out the stops. ”

An interviewer would ask "What research do you do to prepare for a tour?" to a/an Tour Guide to assess the level of preparation that the tour guide undertakes before leading a tour. It is important for the tour guide to be prepared in order to ensure that the tour is enjoyable and informative for all participants.

Example: “ I always start by doing a thorough research of the area that I'm going to be touring. This includes reading up on the history, culture, and any other relevant information that will be helpful in providing an informative and enjoyable experience for my guests. I also like to familiarize myself with the layout of the area so that I can easily navigate and point out key landmarks and attractions. ”

There are a few reasons why an interviewer might ask this question. First, they want to know if the tour guide is aware of the challenges they face in their job. This is important because it shows that the tour guide is willing to take on challenges and is able to identify them. Second, the interviewer wants to know how the tour guide deals with these challenges. This is important because it shows that the tour guide is able to adapt to different situations and is able to find solutions to problems.

Example: “ Some of the challenges that I face as a tour guide include making sure that everyone in the group is able to keep up with the pace of the tour, dealing with difficult questions from visitors, and making sure that everyone stays safe during the tour. Additionally, I often have to deal with large groups of people, which can be challenging to manage. ”

The interviewer is trying to gauge the tour guide's customer service skills. It is important because tour guides need to be able to handle difficult questions and complaints from tour participants in a professional and courteous manner.

Example: “ There is no one-size-fits-all answer to this question, as the best way to handle difficult questions from tour participants will vary depending on the situation. However, some tips on how to handle difficult questions from tour participants include: - remaining calm and professional at all times, even if the question is challenging or unexpected; - taking a moment to think about the question before answering, in order to ensure that you are providing accurate information; - being honest if you do not know the answer to a question, but offering to find out the answer for the participant later; and - politely redirecting the conversation if a participant is asking too many personal or difficult questions. ”

The interviewer is trying to get to know the tour guide on a personal level. By asking about their favorite stories or anecdotes, the interviewer can get a sense of the tour guide's personality and whether they would be a good fit for the company. It is important to ask about the tour guide's favorite stories because it can give the interviewer a better idea of what kind of person they are.

Example: “ Some of my favorite stories or anecdotes from my tours include the time I took a group of tourists to see the Statue of Liberty. One of the tourists, a young woman, was so excited to see the statue up close that she started crying. It was a really special moment for her and it made me feel really good to be able to share that experience with her. Another one of my favorites is from a tour I did of the Grand Canyon. We were all standing at the edge of the canyon, just taking in the incredible view, when one of the tourists said, "You know, this is one of those moments where you just have to stop and appreciate how lucky we are to be alive." It was such a simple but profound statement and it really made me think about how lucky we all are to be able to experience this amazing world we live in. ”

The interviewer is asking this question to gain insight into what the tour guide feels makes their tours special or unique. It is important for the interviewer to know this because it will give them a better understanding of how the tour guide plans to market their tours and what they feel sets them apart from the competition. This information can be used to help the interviewer determine if the tour guide is a good fit for the company.

Example: “ I believe that our tours are set apart from others because of the quality of our tour guides. Our tour guides are some of the best in the business and they really know how to show our guests a good time. They are also very knowledgeable about the area and can answer any questions that our guests may have. ”

The interviewer is trying to gauge the tour guide's knowledge of the industry and what they believe are the most important aspects of a successful tour. This question allows the interviewer to get a better understanding of the tour guide's priorities and how they would approach their job. It also allows the interviewer to see if the tour guide is able to think critically about the industry and identify key elements that are necessary for a successful tour.

Example: “ There are many elements that contribute to a successful tour, but some of the most important ones include having an engaging and knowledgeable tour guide, providing interesting and accurate information about the places being visited, having a well-organized itinerary, and making sure the group stays together and on schedule. ”

The interviewer is trying to gauge whether the tour guide is aware of the importance of providing an enjoyable and informative experience for all participants. It is important because it helps to create repeat customers and word-of-mouth marketing for the business.

Example: “ There are a few key things that I do to ensure that my tours are enjoyable and informative for all participants. First, I make sure to do my research ahead of time so that I am well-versed in the subject matter. This way, I can answer any questions that come up and keep the tour interesting. Secondly, I try to mix up the tour a bit by adding in some fun facts or stories. This helps to keep everyone engaged and makes the experience more memorable. Finally, I always make sure to leave time for questions at the end so that everyone has a chance to voice their thoughts and get clarification on anything they didn't understand. ”

An interviewer might ask "What are some of your tips for making the most of a tour?" to a tour guide in order to get insights into the tour guide's methods for ensuring that tour participants have a positive experience. It is important to get tips from a tour guide because they are typically experienced in leading tours and helping people to enjoy the experience. By getting tips from a tour guide, an interviewer can learn about how to make a tour more enjoyable for participants.

Example: “ There are a few things you can do to make the most of your tour: 1. Arrive early or on time. This will give you a chance to explore the area and get your bearings before the tour starts. 2. Dress comfortably. You'll be doing a lot of walking, so make sure you're wearing comfortable shoes and clothing. 3. Bring water and snacks. Tours can be long, and you don't want to get hungry or thirsty halfway through. 4. Pay attention to the guide. They're there to provide information and answer questions, so take advantage of their knowledge! 5. Ask questions. If you're curious about something, don't be afraid to ask the guide or other members of the group. 6. Take photos. Tours are a great opportunity to take photos of new places and people. Just be respectful and don't get in the way of other tourists. 7. Enjoy yourself! tours are meant to be fun, so relax and enjoy the experience. ”

The interviewer is asking this question to gauge the tour guide's ability to think on their feet and deal with unexpected situations. This is important because it shows whether the tour guide is able to adapt and improvise when things do not go according to plan.

Example: “ If an unexpected situation arises during a tour, the first thing I would do is assess the situation and determine if it is something that can be handled quickly and easily or if it requires more time and attention. If it is something that can be handled quickly, I will take care of it right away. If it is something that requires more time and attention, I will notify the tour group of the situation and let them know that we may need to adjust the itinerary accordingly. I will then work with the tour group to come up with an alternate plan that everyone is comfortable with. ”

An interviewer might ask this question to get a sense of the tour guide's knowledge of the area and their ability to make recommendations to visitors. It is important to be able to make recommendations to visitors because they may be unfamiliar with the area and will be relying on the tour guide for guidance.

Example: “ There are plenty of great places to eat and drink near the tour sites. For example, if you're looking for a quick bite, there's a great little cafe called The Daily Grind just a block away from the tour sites. If you're looking for something a bit more substantial, there are plenty of great restaurants nearby as well. And of course, no visit to the area would be complete without stopping by one of the many bars for a drink or two. ”

There are a few reasons why an interviewer might ask this question. They could be trying to get to know the person better on a personal level, or they might be trying to gauge whether the person is well-rounded and has other interests outside of their job. This question can also help the interviewer get a sense of what kind of person the tour guide is and whether they would be a good fit for the company.

Example: “ I love to travel and explore new places, so being a tour guide is the perfect job for me! Outside of work, I enjoy hiking, biking, and spending time outdoors. I also love to learn about different cultures and histories, so I often read books or visit museums in my free time. ”

Related Interview Questions

- Tour Coordinator

- Tour Manager

- Tourism Management

Get Daily Travel Tips & Deals!

By proceeding, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

20 Questions to Ask Before Booking a Tour