The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Hospital Emergency Room Visits per 1,000 Population by Ownership Type

Data are loading.

- Hospital Utilization

- HEDIS Measures and Technical Resources

- Emergency Department Utilization

Emergency Department Utilization (EDU)

Assesses emergency department (ED) utilization among commercial (18 and older) and Medicare (18 and older) health plan members. Plans report observed rates of ED use and a predicted rate of ED use based on the health of the member population. The observed and expected rates are used to calculate a calibrated observed-to-expected ratio that assesses whether plans had more, the same or less emergency department visits than expected, while accounting for incremental improvements across all plans over time. The observed-to-expected ratio is multiplied by the emergency department visit rate across all health plans to produce a risk-standardized rate which allows for national comparison.

Why It Matters

ED visits are a high-intensity service and a cost burden on the health care system, as well as on patients. Some ED events may be attributed to preventable or treatable conditions . A high rate of ED utilization may indicate poor care management, inadequate access to care or poor patient choices, resulting in ED visits that could be prevented. 1,2 Plans can ensure that members receive appropriate, coordinated primary care to address preventable ED visits.

Results – National Averages

Emergency department utilization total rate.

*Lower rates signify better performance.

§ Not available due to CMS suspension of data reporting during COVID-19 pandemic.

This State of Healthcare Quality Report classifies health plans differently than NCQA’s Quality Compass. HMO corresponds to All LOBs (excluding PPO and EPO) within Quality Compass. PPO corresponds to PPO and EPO within Quality Compass.

Figures do not account for changes in the underlying measure that could break trending. Contact Information Products via my.ncqa.org for analysis that accounts for trend breaks.

- Dowd, B., M. Karmarker, T. Swenson, et al. 2014. “Emergency department utilization as a measure of physician performance.” American Journal of Medical Quality 29 (2), 135–43. http://ajm.sagepub.com/content/29/2/135.long

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015. Measures of Care Coordination: Preventable Emergency Department Visits. Accessed at https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/chartbooks/carecoordination/measure2.html

Save your favorite pages and receive notifications whenever they’re updated.

You will be prompted to log in to your NCQA account.

Share this page with a friend or colleague by Email.

We do not share your information with third parties.

Print this page.

Trends in United States emergency department visits and associated charges from 2010 to 2016

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA.

- 2 Department of Health Service Administration, Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH, USA.

- 3 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA; Department of Health Service Administration, Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH, USA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 31519380

- DOI: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.158423

Background: Demographic shifts and care delivery system evolution affect the number of Emergency Department (ED) visits and associated costs. Recent aggregate trends in ED visit rates and charges between 2010 and 2016 have not been evaluated.

Methods: Data from the National Emergency Department Sample, comprising approximately 30 million annual patient visits, were used to estimate the ED visit rate and charges per visit from 2010 to 2016. ED visits were grouped into 144 mutually exclusive clinical categories. Visit rates, compound annual growth rates (CAGRs), and per visit charges were estimated.

Results: From 2010 to 2016, the number of ED visits increased from 128.97 million to 144.82 million; the cumulative growth was 12.29% and the CAGR was 1.95%, while the population grew at a CAGR of 0.73%. Expressed as a population rate, ED visits per 1000 persons increased from 416.92 in 2010 to 448.19 in 2016 (p value <0.001). The mean charges per visit increased from $2061 (standard deviation $2962) in 2010 to $3516 (standard deviation $2962) in 2016; the CAGR was 9.31% (p value <0.001). Of 144 clinical categories, 140 categories had a CAGR for mean charges per visit of at least 5%.

Conclusion: The rate of ED visits per 1000 persons and the mean charge per ED visit increased significantly between 2010 and 2016. Mean charges increased for both high- and low-acuity clinical categories. Visits for the 5 most common clinical categories comprise about 30% of ED visits, and may represent focus areas for increasing the value of ED care.

Keywords: After-hours care; Emergency medicine; Health care costs; Health care economics and organization; Health care expenditures; Hospital charges.

Copyright © 2019 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

- Child, Preschool

- Emergency Service, Hospital / economics*

- Hospital Charges / trends*

- Infant, Newborn

- Middle Aged

- Retrospective Studies

- United States

- Utilization Review

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

Total visits (A), injuries and not-preventable or avoidable visits (B), and visits related to mental health and substance use disorders (C). Q1 indicates quarter 1.

Nonemergent (A), emergent but preventable or avoidable (B), and emergent but primary care–treatable conditions (C). Q1 indicates quarter 1.

eFigure. Total Annual Number of Emergency Department Visits Across States From 2011 to 2017

eTable 1. Indirect Test of the Parallel Trends Assumption in the Pre-ACA Implementation Period

eTable 2. Difference-in-Differences Regression Analyses Estimating Postexpansion Years Separately: Total ED Visits per 1000 Population and Stratified by Medical Urgency

eTable 3. Difference-in-Differences Regression Analyses: Total ED Visits per 1000 Population and Stratified by Medical Urgency Between Florida and New York

- Medicaid Expansion Use and Avoidable Emergency Department Use JAMA Network Open Invited Commentary June 14, 2022 Amber K. Sabbatini, MD, MPH; Jerome Dugan, PhD

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Giannouchos TV , Ukert B , Andrews C. Association of Medicaid Expansion With Emergency Department Visits by Medical Urgency. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2216913. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16913

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Association of Medicaid Expansion With Emergency Department Visits by Medical Urgency

- 1 Department of Health Services Policy & Management, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, Columbia

- 2 Department of Health Policy & Management, School of Public Health, Texas A&M University, College Station

- Invited Commentary Medicaid Expansion Use and Avoidable Emergency Department Use Amber K. Sabbatini, MD, MPH; Jerome Dugan, PhD JAMA Network Open

Question Is Medicaid eligibility expansion associated with changes in emergency department (ED) visits based on the medical urgency of the conditions?

Findings In this cross-sectional study of 80.6 million ED visits across 4 US states, ED visits per 1000 population decreased for states that expanded Medicaid compared with states that did not. This decrease was associated with decreases in ED visits for less-emergent or nonemergent conditions.

Meaning The findings of this study suggest that expanding Medicaid might reduce ED visits for conditions that could be treated in outpatient settings.

Importance Relatively little is known about the association of the Medicaid eligibility expansion under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act with emergency department (ED) visits categorized by medical urgency.

Objective To estimate the association between state Medicaid expansions and ED visits by the urgency of presenting conditions.

Design, Setting, and Participants This cross-sectional study used the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Emergency Department Databases from January 2011 to December 2017 for 2 states that expanded Medicaid in 2014 (New York and Massachusetts) and 2 states that did not (Florida and Georgia). Difference-in-differences regression models were used to estimate the changes in ED visits overall and further stratified by the urgency of the conditions using an updated version of the New York University ED algorithm between the states that expanded Medicaid and those that did not, before and after the expansion. Data were analyzed between June 7 and December 12, 2021.

Exposure State-level Medicaid eligibility expansion.

Main Outcomes and Measures Emergency department visits per 1000 population overall and stratified by medical urgency of the conditions.

Results In total, 80.6 million ED visits by 26.0 million individuals were analyzed. Emergency department visits were concentrated among women (59.3%), non-Hispanic Black individuals (28.3%), non-Hispanic White individuals (47.8%), and those aged 18 to 34 years (47.5%) and 35 to 44 years (20.4%). The rates of ED visits increased by a mean of 2.4 visits in nonexpansion states and decreased by a mean of 2.2 visits in expansion states after 2014, resulting in a significant regression-adjusted decrease of 4.7 visits per 1000 population (95% CI, −7.7 to −1.5; P = .003) in expansion states. Most of this decrease was associated with decreases in ED visits by conditions classified as not emergent (−1.5 visits; 95% CI, −2.4 to −0.7; P < .001), primary care treatable (−1.1 visits; 95% CI, −1.6 to −0.5; P < .001), and potentially preventable (−0.3 visits; 95% CI, −0.5 to −0.1; P = .02). No significant changes were observed for ED visits related to injuries and conditions classified as not preventable (−1.4; 95% CI, −3.1 to 0.3; P = .10), as well as for substance use and mental health disorders (0.0; 95% CI, −0.2 to 0.2; P = .94).

Conclusions and Relevance The findings of this study suggest that Medicaid expansion was associated with decreases in ED visits, for which decreases in ED visits for less medically emergent ED conditions may have been a factor.

Emergency departments (EDs) are a vital component of the US health care system, with more than 140 million visits in 2018 incurring a total cost of approximately $75 billion. 1 Emergency department visits are expected to increase even further in the years ahead, by a projected 12% by 2030. 2 , 3 Although EDs treat patients with acute and unexpected health care conditions, they often serve as a safety net for individuals who are unable to access other health care settings. The use of EDs for nonemergent and preventable medical conditions has been a long-standing challenge in the US health care system. Every year, it is estimated that one-third of all ED visits occur for care that is treatable in primary care settings and preventable. 4 - 6 At an average cost that is many times higher compared with treatment provided at a physician’s office or an urgent care center, some of these visits suggest inefficient allocation of resources and present a cost-saving opportunity. 7

Limited or lack of insurance coverage is a key factor for many ED visits. Uninsured individuals often use the ED as a place to receive routine health care services and are also more likely to experience a health care crisis requiring emergent care owing to the lack of access to outpatient health services and preventive care. 8 Social determinants of health among low-income beneficiaries that perpetuate difficulties in receiving routine health care services could also result in increased ED use for similar reasons. 9 - 11

The expansion of Medicaid eligibility afforded by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) presented a unique opportunity to address this challenge by providing millions of US residents with health insurance coverage that could improve access to routine health care and preventive services. Since 2014, 35 US states have adopted the Medicaid eligibility expansion option, resulting in health insurance uptake for more than 20 million US residents. 12 , 13 Larger gains in enrollment were documented in states that decided to expand Medicaid eligibility to adults less than age 65 years with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level. 14 - 17 The implementation of the Medicaid expansion has also been associated with increased use of preventive services, access to primary care clinicians, affordability, and quality of care. 13 , 16 - 23

However, the evidence on the association between Medicaid expansion and ED use is inconclusive. 18 , 24 Limited or no cost-sharing for preventive and primary care services could lead to a shift of care from the ED setting to outpatient care, after obtaining new or more generous health care coverage. Recent studies reported that Medicaid expansion was associated with decreases in ED visits among individuals who previously reported barriers to outpatient care and those related to opioid use. 25 , 26 However, the expansion could have also increased ED use by eliminating or reducing cost barriers to receiving care in the ED. 18 , 27 - 31 A recent study by Garthwaite and colleagues 32 noted that Medicaid expansion was associated with increases in ED visits for deferrable medical conditions, defined as visits for which the patient has some discretion regarding when and where to seek care.

These results highlight a complex relationship between health insurance and ED use. 33 However, analyses examining only total ED visits may conceal important changes in the composition of the ED visits by medical urgency. A recent study analyzing ED visits after Medicaid expansion highlighted the importance of further studies that examine nonemergent ED use. 24 Hence, there remains a need to categorize ED visits by medical urgency because parameters that divert individuals with different conditions from use of EDs might vary. 34

To address this gap in the literature, we estimated the association between the ACA Medicaid expansion and ED visits, stratified by medical urgency of the visits, using a validated algorithm, and compared 2 Medicaid-expansion states with 2 nonexpansion states.

Our main databases were the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Emergency Department Databases from January 2011 to December 2017. 35 These longitudinal administrative secondary databases include all-payer discharge information for nearly all outpatient (treat and release) ED visits across every general and acute care hospital within a state, similar to previous work. 31 We focused on outpatient ED visits, which account for almost 90% of all ED visits, to identify encounters that can be classified as less emergent. 36 We included data from 4 states (Florida, Georgia, Massachusetts, and New York), which account for almost one-fifth of the US population. Two of these states expanded Medicaid in 2014 (Massachusetts and New York), and the others did not. We included in-state residents aged 18 to 64 years who were covered by Medicaid, private plans or other local, state, or federal plans, or who were uninsured throughout the study period. Medicare enrollees were not included in the study given that individuals enrolled in the program were not directly affected by the Medicaid eligibility expansion and would be unlikely to transition from Medicare to Medicaid as a result of the policy change. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guideline for reporting observational studies. The study was determined to be not human subjects research by the Texas A&M University Institutional Review Board.

Our outcomes of interest were total ED visits and ED visits classified by medical urgency per 1000 population. We obtained publicly available annual state-level population counts for the corresponding age groups to generate ED visits per 1000 residents. 37 We then used the updated version of the New York University ED algorithm to classify each ED visit by medical urgency, based on the primary diagnosis code from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (January 2011 to September 2015) or International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (October 2015 to December 2017). 6 , 38 This algorithm assigns probabilities and classifies each ED visit into 1 or multiple probability-adjusted categories: emergent and not-preventable or avoidable (eg, chest pain, tachycardia); emergent but preventable or avoidable (eg, dehydration); emergent but primary care–treatable (eg, muscle strain); not emergent (eg, low back pain, headache); injury; and alcohol, drug use, and mental health–related issues. We averaged the algorithmically assigned probabilities and grouped ED visits into 5 categories to reflect conditions by medical urgency: (1) not preventable and injury-related, (2) emergent but potentially preventable, (3) emergent but primary care treatable, (4) not emergent, and (5) mental health and substance use disorders. 28 We aggregated data at the state year-quarter level similar to previous work. 24 , 26

The primary exposure was state Medicaid expansion status. We obtained and identified the status of the decisions to expand Medicaid from publicly available resources. 39 Massachusetts and New York adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion provision in January 2014; Georgia and Florida did not.

We also included publicly available, time-varying, state-level variables in our analyses that have been commonly associated with ED use as control variables (percentages of women; non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White individuals; age-group distributions; annual unemployment rate; and percentage of population under 200% of the federal poverty level). 37 , 40 , 41 Race and ethnicity data were obtained from publicly available resources at the state-year level to control for state-level variation. The categorization is how this information was available on the publicly available resource.

We conducted a descriptive analysis for all 4 states and then stratified by expansion status. We then performed difference-in-differences regression analyses to estimate the association of the Medicaid expansion with ED visits that were weighted by each state’s population with state year-quarter as the unit of analysis. 31 This approach enabled us to compare pre-ACA expansion vs post-ACA expansion outcomes in states that implemented the Medicaid expansion (treatment group) with states that did not (control group). Our adjusted regression analyses included all covariates. Robust SEs were used. We also conducted sensitivity analyses without state-level population weights to evaluate the sensitivity of the findings. Moreover, we evaluated the year-by-year difference-in-differences in ED visits by interacting the Medicaid expansion indicator of the states with each year separately. Because Massachusetts implemented a large health reform before the ACA to provide near-universal health insurance coverage, we conducted supplemental analyses by only comparing New York with Florida. These 2 states had similar rates of ED visits in the preexpansion period.

One critical assumption of the difference-in-differences model is that both the treatment and control groups exhibited parallel trends in the prepolicy implementation period. 42 We examined trends in the pre-ACA expansion period (2011-2013) by conducting regressions across all outcomes with an interaction term between year-quarters and the expansion status dummy as the primary independent variable. The results showed little evidence of diverging trends and provided support of the parallel trends assumption (eTable 1 in the Supplement ). Two-tailed tests were used, and statistical significance was considered at P < .05. We managed the data using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and all statistical analyses were performed between June 7 and December 12, 2021, using Stata, version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC).

Our study included 80.6 million ED visits by 26.0 million individuals. Table 1 presents descriptive information for all states and stratified by Medicaid expansion status from 2011 to 2017. Overall, 59.3% of visits were by women and 40.7% by men, with 67.9% of the visits by those aged between 18 and 44 years (18-34 years, 47.5%; 35-44 years, 20.4%). With classification by race and ethnicity status, 28.3% of the visits were by non-Hispanic Black individuals, 15.8% by Hispanic individuals, 47.8% by non-Hispanic White individuals, and 8.1% by those of other racial and ethnic groups (ie, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, or other race and ethnicity). Across all states, about one-third (32.1%) of the ED visits were for injury-related or not-preventable conditions, 22.9% were classified as not emergent, 21.8% as primary care treatable, and 5.3% as potentially preventable. Visits for mental health and substance use disorders accounted for 4.8% of all visits but were relatively higher in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states (6.4% vs 3.3%; P < .001). The share of Medicaid-paid ED visits was disproportionately higher in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states (41.5% vs 25.4%; P < .001), and the opposite was observed for the uninsured population (11.2% vs 35.1%; P < .001).

Overall, total ED visits per 1000 population remained similar in the pre- and post-ACA periods (52.1 vs 52.3 visits) while the total number of ED visits increased by approximately 1% per year on average ( Figure 1 ; eFigure in the Supplement ). Figure 1 presents the trends in total ED visits, injuries and not-preventable or avoidable issues, and mental health–related or substance use issues, and Figure 2 shows the trends by medical urgency per 1000 population from 2011 to 2017 in expansion and nonexpansion states. Across all outcomes, states had relatively similar ED visit trends before January 2014 (preexpansion period). Total ED visits per 1000 population decreased after 2014 in expansion states (4.3% mean relative decrease) and increased in nonexpansion states (4.5% mean relative increase). Emergency department visits for conditions classified as potentially preventable (6.1% mean relative decrease) and primary care treatable (3.2% mean relative decrease) decreased only in expansion states, and those for not-emergent conditions decreased in both expansion (10.3% mean relative decrease) and nonexpansion (0.7% mean relative decrease) states. Visits for injuries and not-preventable conditions decreased in both expansion and nonexpansion states (mean relative decrease 11.3% and 2.0%), and those related to mental health and substance use disorders followed relatively flat trends across expansion and nonexpansion states.

Table 2 reports unadjusted and adjusted regression difference-in-differences results. Total ED visits per 1000 population increased by 2.4 visits in nonexpansion states and decreased by 2.2 visits in Medicaid expansion states after 2014 compared with the pre-ACA period. This change resulted in a significant regression-adjusted decrease of 4.7 ED visits per 1000 population (95% CI, −7.7 to −1.5; P = .003). Compared with nonexpansion states, the ACA was associated with decreases of 1.5 ED visits per 1000 population (95% CI, −2.4 to −0.7; P < .001) for not-emergent, 1.1 ED visits per 1000 population (95% CI, −1.6 to −0.5; P < .001) for primary care–treatable, and 0.3 ED visits per 1000 population (95% CI, −0.5 to −0.1; P = .02) for potentially preventable conditions in states that opted in the expansion of Medicaid. We did not observe any significant differences in ED visits for injuries or not-preventable conditions (−1.4; 95% CI, −3.1 to 0.3; P = .10), and visits related to mental health and substance disorders (0.0; 95% CI, −0.2 to 0.2; P = .94). The year-by-year trend difference-in-differences in the post–Medicaid expansion period showed that ED visits overall decreased each year as well as for less-emergent conditions (eTable 2 in the Supplement ). Medicaid expansion was also associated with decreases in ED visits for injuries and not-preventable conditions, but only after the third year of the policy implementation (2016: −2.6; 95% CI, −4.3 to −0.8; P = .004; 2017: −3.3; 95% CI, −5.6 to −1.1; P = .004). In addition, the sensitivity analyses without state population size-adjusted weights and the sample comparing only New York with Florida yielded similar results (eTable 3 in the Supplement ).

In this analysis of 80.6 million ED visits from 2011 to 2017 in 4 states, we found that Medicaid expansion was associated with a significant decrease of 4.7 ED visits per 1000 population in states that expanded Medicaid compared with states that did not, for which decreases in ED visits for less-emergent or not-emergent conditions may be a factor. We did not observe any major policy-related differences in ED visits for mental health and substance use disorders, injuries, and nonpreventable conditions overall.

Our results are consistent with previous work that found significant decreases in ED visits following the ACA implementation in states that expanded Medicaid. 17 , 25 , 42 , 43 Our study expands the evidence using 4 postexpansion years and focuses on populous states that might more specifically represent the national trends in ED visits. 44 Previous work with diverging results generally assessed changes in ED visits after 1 or 2 years postexpansion, focused their analysis on different states and populations, or reviewed outcomes using different definitions of not-emergent ED visits. 25 , 31 , 32

The observed decreases in ED visits concurrently occurred with increases in availability and access to primary care, and more primary care professionals accepting patients with Medicaid coverage to higher Medicaid payment rates. 17 , 25 , 43 , 45 - 47 Furthermore, decreases in Medicaid expansion states were concentrated in conditions that were less-emergent or not medically emergent, suggesting that access to preventive services could have substituted ED visits, improved health, and stabilized health conditions, which rendered ED use not necessary. 25 , 48 - 51 Before implementation of the ACA, EDs were the only access point for many individuals owing to financial difficulties in identifying cost-effective avenues of care. 52

However, ED visits for potentially preventable, primary care–treatable, and not-emergent conditions made up more than 40% of all ED visits even after states expanded Medicaid. 4 , 5 Although expanding health insurance coverage may be important, it does not guarantee access to medical care. Time and access barriers to outpatient care, such as appointment availability, inconvenient office hours, underinsurance, infrastructure barriers (eg, waiting times and lack of diagnostic capabilities of primary care offices), and prevailing social needs (eg, housing and food instability), are commonly cited reasons for nonemergent presentations to EDs even among insured individuals. 4 , 5 , 9 , 10 , 25 , 33

The high rates of ED visits for not-emergent conditions also raise concerns about the quality of care that some patients receive in primary care and outpatient settings. Dissatisfaction with primary care professionals, language barriers and unclear instructions, physician referrals to the ED, convenient operating hours, and the need for a second opinion are additional factors that predispose ED use. 4 , 10 Furthermore, many individuals are not equipped to accurately perceive the severity of their condition and might overestimate the need for emergency care, particularly after regular office hours or when outpatient care is not available. In addition, lack of knowledge about viable alternatives and limited information about outpatient clinicians’ resources may further predispose nonemergent ED presentations. 4 , 25 , 53 , 54

We also observed a small increase in ED visits related to mental health and substance use disorders across both expansion and nonexpansion states. 23 Our data fall within the years of the second wave of the opioid epidemic in the US, when ED visits for substance use disorders increased by more than 30%. 55 , 56 Factors such as fear of stigmatization, service availability, and health plan benefit constraints are additional barriers and considerations that these individuals face before entering treatments. 57 - 59

Beyond the ACA expansion, we also noted an annual increase in the total number of ED visits of approximately 1%, almost twice the rate of annual population growth. 2 The increasing demand for ED services warrants new and revised treatment protocols and models of care among emergency medicine professionals. Policies that might contain ED use include higher outpatient Medicaid reimbursement rates for behavioral and substance use treatment services and promoting the use of telemedicine. 16 , 31 , 46 , 55 , 60 In addition, targeted outreach efforts to increase health plan enrollment may yield long-term benefits, as more than half of the uninsured population is eligible for Medicaid or subsidized coverage. 61

However, addressing only medical and health care system factors will not reverse the social and economic circumstances that exacerbate access to care and chronic health problems. Synergies between medical and social needs demonstrated that coordination of medical, behavioral, and social services can improve health outcomes and contain ED use. 62 Investments in social welfare services, data sharing, and integration of primary care, housing, food, and psychosocial services are needed to improve health and allocate resources more effectively. In addition, investments in health care professional education to promote patient engagement in the development of personal care plans with need-oriented goal setting are necessary to enable the health care system to evolve from medical care centered to patient centered.

Our study has limitations. First, we used data from only 4 states that exhibit similar ED visit rates with national trends, but findings may differ by state, as previous work using similar methods but different states found increases in ED visits. 31 However, the difference in the results might be associated with either the use of more states or the use of data only including the first year of the Medicaid expansion. In addition, although the State Emergency Department Databases data represent almost 90% of all ED visits, we did not include data on ED visits that resulted in hospital admissions; thus, findings might not be generalizable to all ED visits. Second, there are differences in the proportion of each state’s population that became eligible for Medicaid in 2014. 24 Massachusetts implemented a partial Medicaid expansion in 2006 and consequently added far fewer residents to Medicaid in 2014. However, this limitation is likely to result in an underestimation of the association of Medicaid expansion with observed trends rather than an overestimation. Third, the transition from International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision to International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision occurred during the study period, resulting in a shift in the codes used to identify visit types. Nonetheless, sensitivity tests conducted to check for bias in visit types, including unclassified visits, did not result in any significant change in our study findings. Fourth, owing to the nature of the New York University algorithm, it is possible that some categories were nonmutually exclusive and, thus, some conditions could be assigned to more than one group, which could bias our estimates. Fifth, the discharge diagnoses based on the retrospective assignment of probabilities by the New York University algorithm do not capture the patients’ perception of risk at the time of the episode and ED visit. Sixth, the retrospective design may be subject to potential unobserved confounders that could bias our results.

The findings of this study suggest that the Medicaid expansion that occurred with implementation of the ACA was associated with significant reductions in ED visits in states that expanded Medicaid, for which decreases in ED visits for less medically emergent conditions, some of which could potentially be treated in other settings, may be a factor. However, ED visits for potentially preventable and primary care–treatable conditions continued to account for a large share of all ED visits, even in expansion states. As policy makers debate the future of the ACA and public support for a single-payer national health plan increases, our findings provide further data suggesting that investing in health insurance can reduce ED use for nonemergent medical conditions.

Accepted for Publication: April 19, 2022.

Published: June 14, 2022. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.16913

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2022 Giannouchos TV et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Theodoros V. Giannouchos, PhD, MS, Department of Health Services Policy & Management, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, 915 Greene St, Columbia, SC 29208 ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions : Drs Giannouchos, Ukert had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Giannouchos, Ukert.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Giannouchos, Ukert.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Giannouchos.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Giannouchos.

Supervision: Giannouchos, Ukert.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Additional Information: The Population Informatics Lab provided access to the data and the Texas Virtual Data Library (ViDaL) funded by the Texas A&M University Research Development Fund the secure computing infrastructure required in this research.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

The Latest Emergency Department Utilization Numbers Are In

T he Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released its statistical survey of emergency department visits for 2016 on April 1. Called the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), it is a wealth of information for emergency physicians and will guide the data and trends for the emergency services for which they are responsible. 1

You Might Also Like

- Emergency Department Volume Increase Trend Continues Into 2014

- Long-Term Trends in Emergency Department Visits, Patient Care Highlighted in National Reports

- 2015 Emergency Department Survey Shows Spike in Volume, Structural Changes, Patient Boarding Concerns

Explore This Issue

The numbers.

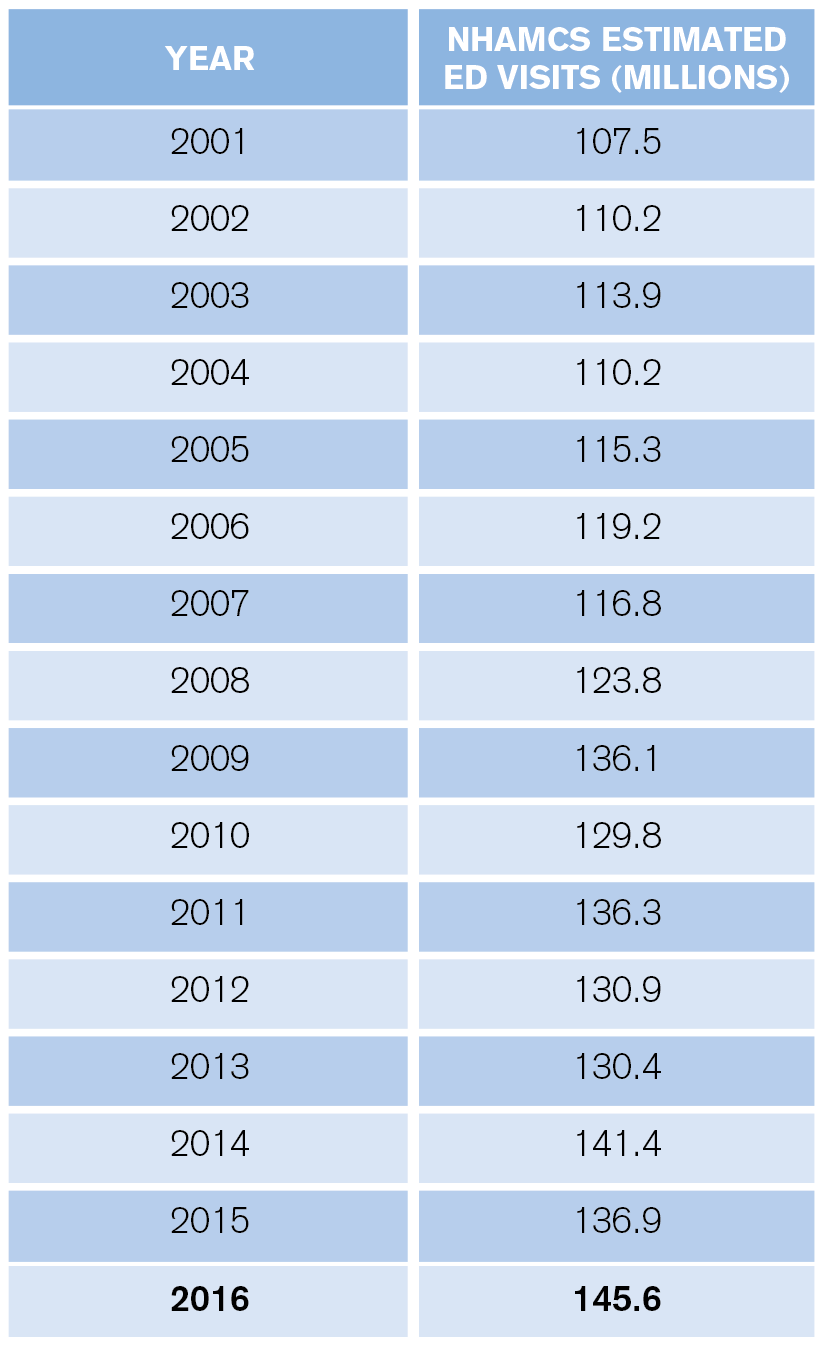

ED visit estimates increased from 136.9 million in 2015 to 145.6 million in 2016, a jump of 6.4 percent. The 10-year volume change is 24.7 percent, and for the past 20 years, the increase has totaled 61.2 percent (the 1996 ED visit estimate was 90.3 million). The past 15 years of volume estimates appear in Table 1.

These data may not match the experience in every emergency department and every community. First, the CDC typically estimates the lowest volume of ED visits, and the NHAMCS does not include visits to freestanding emergency departments. Second, there are changing patterns of ED use based on community sources of unscheduled care. Third, the patchwork of primary care systems in the country influences the number of ED visits locally.

(click for larger image) Table 1: Estimated Annual ED Visits

What is apparent from the CDC data is that the trend of emergency departments seeing older, sicker patients, combined with continued growth in retail clinics, telehealth, and other sources of care for nonemergent problems, will yield a net increase in the average severity and complexity of patients seen in full-service emergency departments.

Who Are the Patients?

ED visits increased from 369 to 458 visits per 1,000 people between 1995 and 2016. High utilizers continue to include infants, nursing home residents, the homeless, black persons, and people over age 75.

Infants under age 1 had 987 visits per 1,000 persons. This is relatively high utilization and represents an opportunity for parent education.

There were roughly 2.2 million visits for patients who reside in nursing homes, for a utilization of 1,594 visits per 1,000 residents. Approximately 33 percent of nursing home patient ED visits resulted in hospital admission (739,000), with an average length of hospital stay of 5.7 days.

Persons classified as homeless represented a larger visit load for EDs compared with prior years. In 2016, homeless persons accounted for an estimated 1,446,000 visits, a rate of 2,630 visits per 1,000 estimated number of homeless persons. Those visits equal roughly 1 percent of total ED visits.

The CDC also categorized visit rates for white, black, Hispanic, and other races/ethnicities. The visit rate was 435 visits per 1,000 white people, 404 visits per 1,000 Hispanics, and 804 visits per 1,000 black people. The visit rate was 172 visits per 1,000 persons of other races (ie, Asian, native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska native, and persons with more than one race).

The ED population is aging in line with national demographics. Persons over age 65 accounted for 15.8 percent of ED visits, and persons age 75 and older had 605 visits per 1,000 in 2016. Thus, emergency departments must prepare for larger numbers of patients and develop processes tailored to older persons. In addition, older patients require more workup, treatment, and, thus, more time in the department.

Finally, because older patients are admitted to the hospital more often, they spend more time as ED boarders. Planning for new or renovating old emergency departments should account for these shifting demographics.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

Topics: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance Utilization

A Sobering Year for Emergency Departments and Their Patients

A First Look at Emergency Department Data for 2022

Emergency Department Patient Challenges to Come

Current issue.

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 04 – April 2024

Download PDF

About the Author

James J. Augustine, MD, FACEP

James J. Augustine, MD, FACEP, is national director of prehospital strategy for US Acute Care Solutions in Canton, Ohio; clinical professor of emergency medicine at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio; and vice president of the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance.

View this author's posts »

No Responses to “The Latest Emergency Department Utilization Numbers Are In”

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

CMS Newsroom

Search cms.gov.

- Physician Fee Schedule

- Local Coverage Determination

- Medically Unlikely Edits

Quality Measures

Now available! Our new Provider Data Catalog (PDC) makes it easier for you to search and download our publicly reported data. We’ve also improved Medicare’s compare sites .

December 22, 2023

MDS 3.0 QM User's Manual v16.0 Effective October 1, 2023 and Associated User Manual Files – Corrected Manual Now Available

In response to provider questions related to the Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 Quality Measures (QM) User’s Manual posted on September 20, 2023, an updated MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual v16.0, effective 10-1-2023, is now posted. Additionally, the updated .zip file titled MDS 3.0 QM User's Manual v16.0 Effective 10-1-2023 and Associated User Manual Files.zip includes a complete set of six files:

- MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual V16.0 (MDS-3.0-QM-USERS-MANUAL-v16.pdf) contains detailed specifications for the MDS 3.0 quality measures effective October 1, 2023, as well as the Quality Measure Reporting Module Table that documents the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) quality measures calculated using MDS 3.0 data and reported in a CMS reporting module.

The MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual V16.0 has been updated to remediate a previous error in the Exclusions list of the (i) Percent of Residents Who Used Antianxiety or Hypnotic Medication (LS) and (ii) Prevalence of Antianxiety/Hypnotic Use (LS) measures. Rather than excluding both N0415B1 = [-] and N0415D1 = [-] for assessments with target dates on or after October 1, 2023, the previous specifications duplicated MDS v1.18.11 item N0415B1 = [-] as an exclusion for assessments with target dates on or after 10/01/2023. Additionally, where applicable, the file was edited for grammar and CBE endorsement status.

- Risk Adjustment Appendix File for MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual V15.0 (Risk-Adjustment-Appendix-File-for-MDS-3.0-Quality-Measures-User's-Manual-V15.xlsx) contains the logistic regression coefficients used for risk adjustment.

Note: A new Risk Adjustment Appendix file to accompany V16.0 of the MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual is not available as there is not enough data to calculate coefficients for measures which utilize Section GG data in risk-adjustment. An updated Risk Adjustment Appendix file will be published when technically feasible. In the meantime, readers can continue to refer to V15.0 of the Risk Adjustment Appendix for the most current risk adjustment coefficients for the applicable measures.

- Nursing Home Compare Claims-based Quality Measure Technical Specifications (Nursing Home Compare Claims-based Measures Tech Specs 2023 Update 03-20-2023.pdf) contains detailed technical specifications for all Nursing Home Claims-based Quality Measures.

- Nursing Home Compare Quality Measures Technical Specifications Appendix (APPENDIX - Claims-based Measures Technical Specifications Updates 03-20-23.pdf) contains tables and appendices related to the Nursing Home Compare Claims-based Quality Measures.

- Skilled Nursing Facility Quality Reporting Program (SNF QRP) Measure Calculations and Reporting User’s Manual V5.0 (snf-qm-calculations-and-reporting-users-manual-v5.0.pdf) contains detailed specifications for all SNF QRP Quality Measures effective October 1, 2023.

- Risk Adjustment Appendix File for the SNF QRP Measure’s Calculations and Reporting User’s Manual V5.0 (Risk-Adjustment-Appendix-File-for-SNF-Effective-10-01-2023.xlsx) contains risk-adjustment values used to calculate SNF QRP risk-adjusted quality measures.

The updated .zip file is available in the Downloads section of this webpage.

September 21, 2023

Public Reporting Timeline for NHQI Measures Impacted by the MDS 3.0 G-GG Transition

Effective October 1, 2023, Minimum Data Set (MDS) Section G: Functional Status will be replaced with Section GG: Functional Abilities and Goals . This transition will significantly impact the specifications of the following Nursing Home Quality Initiative (NHQI) Quality Measures (QMs):

- Percentage of Residents Who Made Improvements in Function (Short Stay)

- Percent of Residents Whose Need for Help with Activities of Daily Living Has Increased (Long Stay)

- Percent of Residents Whose Ability to Move Independently Worsened (Long Stay)

- Percent of High-Risk Residents with Pressure Ulcers (Long Stay)

- Percent of Low-Risk Residents Who Lose Control of Their Bowel and Bladder (Long Stay)

To address the impact of this Section G to GG transition on the 2024 Nursing Home Care Compare public reporting schedule, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will freeze (hold constant) the aforementioned QMs on Nursing Home Care Compare in April 2024. In October 2024, CMS will replace the Percentage of Residents Who Made Improvements in Function (Short Stay) measure with the new Discharge Function Score measure which was finalized in the FY2024 SNF PPS Final Rule for use in the Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) Quality Reporting Program (QRP) and the SNF Value Based Purchasing (VBP) program. The remaining four measures will continue to be frozen until January 2025 while the data for the equivalent measures are collected.

Please see the Updates to Nursing Home Care Compare Staffing and Quality Measures Quality, Safety & Oversight Group (QSO) memo for more information.

For more information on the new and re-specified QMs please see the MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual V16.0, which can be found in the Downloads section of this webpage.

September 20, 2023

MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual V16.0– Now Available

The Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 Quality Measures (QM) User’s Manual Version (V)16.0 is now available. The MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual V16.0 contains detailed specifications for the MDS 3.0 QMs and includes a Notable Changes section that summarizes the major changes from MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual V15.0.

Major changes to the manual involve the re-specification and replacement of QMs that use items impacted by the MDS transition from v1.17.2 to v1.18.11, effective October 1, 2023 (i.e., Section G items are replaced by Section GG items).

The MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual V16.0 can be found in the Downloads section of this webpage and the MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual V15.0 has been moved to the Quality Measures Archive webpage.

One file related to the MDS 3.0 QM User’s Manual has been posted:

- MDS-3.0-QM-USER'S-MANUAL-v16.0.pdf contains detailed specifications for the MDS 3.0 quality measures, as well as the Quality Measure Reporting Module Table that documents CMS quality measures calculated using MDS 3.0 data and reported in a CMS reporting module. MDS-3.0-QM-USER'S-MANUAL-v16.0.pdf is available under the Downloads section of this webpage.

The current nursing home quality measures are:

Short Stay Quality Measures

- Percent of Short-Stay Residents Who Were Re-Hospitalized after a Nursing Home Admission

- Percent of Short-Stay Residents Who Have Had an Outpatient Emergency Department Visit

- Percent of Residents Who Newly Received an Antipsychotic Medication

- Changes in Skin Integrity Post-Acute Care: Pressure Ulcer/Injury

- Percent of Residents Who Were Assessed and Appropriately Given the Seasonal Influenza Vaccine

- Percent of Residents Who Received the Seasonal Influenza Vaccine*

- Percent of Residents Who Were Offered and Declined the Seasonal Influenza Vaccine*

- Percent of Residents Who Did Not Receive, Due to Medical Contraindication, the Seasonal Influenza Vaccine*

- Percent of Residents Who Were Assessed and Appropriately Given the Pneumococcal Vaccine

- Percent of Residents Who Received the Pneumococcal Vaccine*

- Percent of Residents Who Were Offered and Declined the Pneumococcal Vaccine*

- Percent of Residents Who Did Not Receive, Due to Medical Contraindication, the Pneumococcal Vaccine*

- Discharge Function Score

* These measures are not publicly reported but available for provider preview.

Long Stay Quality Measures

- Number of Hospitalizations per 1,000 Long-Stay Resident Days

- Number of Outpatient Emergency Department Visits per 1,000 Long-Stay Resident Days

- Percent of Residents Who Received an Antipsychotic Medication

- Percent of Residents Experiencing One or More Falls with Major Injury

- Percent of High-Risk Residents with Pressure Ulcers

- Percent of Residents with a Urinary Tract Infection

- Percent of Residents Who Have or Had a Catheter Inserted and Left in Their Bladder

- Percent of Residents Whose Ability to Walk Independently Worsened

- Percent of Residents Whose Need for Help with Activities of Daily Living Has Increased

- Percent of Residents Assessed and Appropriately Given the Seasonal Influenza Vaccine

- Percent of Residents Assessed and Appropriately Given the Pneumococcal Vaccine

- Percent of Residents Who Were Physically Restrained

- Percent of Low-Risk Residents Who Lose Control of Their Bowels or Bladder

- Percent of Residents Who Lose Too Much Weight

- Percent of Residents Who Have Depressive Symptoms

- Percent of Residents Who Used Antianxiety or Hypnotic Medication

- Percent of Residents with Pressure Ulcers

- Percent of Residents with New ore Worsened Bowel or Bladder Incontinence

Quality measure specifications are available in the QM Users’ Manual download file, which can be found under the Downloads section below. A sub-group of quality measures are incorporated into the Five-Star Quality Rating System and used to determine scoring for the quality measures domain on Nursing Home Compare.

MDS-3.0-QM_Users_Manual_v15_Update_3-22-2023 (ZIP)

MDS-QM-User's-Manual-v16.0-Effective-10-1-2023-and-Associated-User-Manual Files (ZIP)

Related Links

- Five-Star Quality Rating System

How to Calculate Admits Per 1000

by Victoria Lee Blackstone

Published on 8 Nov 2018

"Admits per 1,000" is a term that represents how many patients are admitted to a hospital, healthcare facility or treatment center for every 1,000 people who seek help there. Many patients enter through the emergency department or in-patient admissions at regional hospitals, but other types of medical providers also are included, such as psychiatric and chemical-dependency facilities. Regardless of the type of medical facility, admits per 1,000 is a ratio that's calculated using a simple math equation.

You can calculate the number of admits per 1,000 visits by taking the number of admits over a given time, multiplying it by 1,000, and then dividing it by the total number of people who visited the facility during that identical duration of time.

How to Calculate Admits Per Thousand

In order to calculate the number of admits per thousand, you must first determine the number of patients admitted to a hospital, healthcare facility or treatment center in a given time period. Next, multiply this number by 1,000. Lastly, divide the result by the total number of people who visited that medical provider, including those who were not ultimately admitted to the facility.

By using the calculation above, if a hospital admits 500 patients from a total of 800 people who visited the hospital, the number of admits per thousand is 625 (500 x 1,000 divided by 800 = 625).

Why Is This Calculation Important?

Hospitals and other in-house medical facilities face ongoing challenges as they prepare budgets and cost estimates for future years. Admits per 1,000 is one way they can project a future year's financial needs based on the past year's actual patient statistics. This simple equation can help healthcare centers find solutions to minimize their costs, manage their supplies, modify their medical practices and adjust their budgets.

Benchmarking to Compare Standards

Admits per 1,000 also provides a benchmark, or point of reference, from which one hospital may measure its performance based on one or more other hospitals. Benchmarking can compare one hospital's statistics to other hospitals, which may be in the same community/county, state or national database. Hospitals may use the benchmarking tool to help them identify areas that need improvement toward their ongoing goal of providing the best patient care at the best costs.

Identifying Proactive Benefits

Although monitoring expenses is a primary focus of calculating admits per 1,000, hospitals can also use this calculation to help identify industry trends as they begin to emerge. This proactive management tool allows hospitals to stay on the forefront of subtle shifts in patient care so they can quickly identify and eliminate wasteful spending and unnecessary supply costs and other expenses. With a total of 140-plus million hospital visits each year just to emergency departments, according to a 2014 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, the data collected from a hospital's admits-per-1,000 calculations have significant potential to reduce national healthcare costs.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Number of visits per 100 persons: 42.7. Number of emergency department visits resulting in hospital admission: 18.3 million. Number of emergency department visits resulting in admission to critical care unit: 2.8 million. Percent of visits with patient seen in fewer than 15 minutes: 41.8%. Percent of visits resulting in hospital admission: 13.1%.

Affordable Care Act. Medicare Drug Costs. Home. State Health Facts. Providers & Service Use. Hospital Utilization. Hospital Emergency Room Visits per 1,000….

Assesses emergency department (ED) utilization among commercial (18 and older) and Medicare (18 and older) health plan members. Plans report observed rates of ED use and a predicted rate of ED use based on the health of the member population. The observed and expected rates are used to calculate a calibrated observed-to-expected ratio that ...

Data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. The overall emergency department (ED) visit rate was 43 visits per 100 people in 2021. ED visit rates were highest for infants under age 1 year (103 visits per 100 infants) and adults aged 75 and over (66 per 100 people). The ED visit rate for Black or African-American non-Hispanic ...

In 2018, the overall rate of ED visits was 439 per 1,000 population. The rate was more than six times higher for treat-and-release ED visits than for ED visits resulting in hospital admission (378 vs. 61 per 1,000). The highest rates of ED visits were among females, those aged 65 years and older, individuals

The majority of ED visits (86 percent) resulted in treatment and release (378 per 1,000 population). The two most common general reasons for these visits were (1) injuries and poisonings and (2) symptoms, signs, and abnormal findings. The most common specific reasons for treat-and-release ED visits were abdominal pain, acute upper respiratory ...

The ED visit rate for adults aged 75 and over was 60 visits per 100 persons, which was higher than the rates for all other age groups, except infants under age 1 year. ED visit rates were similar for all other age groups, ranging from 35 to 41 visits per 100 persons. Figure 2. Emergency department visit rates, by age group: United States, 2018

The rate of ED visits per 1000 persons and the mean charge per ED visit increased significantly between 2010 and 2016. Mean charges increased for both high- and low-acuity clinical categories. Visits for the 5 most common clinical categories comprise about 30% of ED visits, and may represent focus a …

The rates of ED visits increased by a mean of 2.4 visits in nonexpansion states and decreased by a mean of 2.2 visits in expansion states after 2014, resulting in a significant regression-adjusted decrease of 4.7 visits per 1000 population (95% CI, −7.7 to −1.5; P = .003) in expansion states.

The visit rate was 172 visits per 1,000 persons of other races (ie, Asian, native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska native, and persons with more than one race). The ED population is aging in line with national demographics. Persons over age 65 accounted for 15.8 percent of ED visits, and persons age 75 and older had ...

The lower ED visit rate in the West occurred for ED visits with admission to the same hospital (48 per 1,000 population) and ED visits resulting in discharge (273 per 1,000 population). The proportions of ED visits that were attributable to each expected primary payer are provided in Figure 2.

Description. Outpatient Emergency Department (ED) Visits per 1,000 Member Months. These specifications are derived from a measure developed by the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, in collaboration with Medicaid delivery system stakeholders, as part of the 5732/1519 performance measure development process.

The researchers found that the overall emergency department visit rate for assault was 4.5 visits per 1,000 people per year during 2019 to 2021, with the highest rates seen for those aged 18 to 24 and 25 to 44 years (9.2 and 7.7, respectively), which declined with age.

Number of Hospitalizations per 1,000 Long-Stay Resident Days; Number of Outpatient Emergency Department Visits per 1,000 Long-Stay Resident Days; Percent of Residents Who Received an Antipsychotic Medication; Percent of Residents Experiencing One or More Falls with Major Injury; Percent of High-Risk Residents with Pressure Ulcers

In order to calculate the number of admits per thousand, you must first determine the number of patients admitted to a hospital, healthcare facility or treatment center in a given time period. Next, multiply this number by 1,000. Lastly, divide the result by the total number of people who visited that medical provider, including those who were ...

Key findings. Data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. The overall emergency department (ED) visit rate was 40 visits per 100 people in 2020. The ED visit rate was highest for infants under age 1 year (68 visits per 100 infants), followed by adults aged 75 and over (63 per 100 people). The ED visit rate for non-Hispanic ...

ED visits per 1000 member months Focus: Concentrate on ambulatory management of chronic disease, right care at the right place, right time, and connected to care before and after an ED visit. Learn and improve: Identify what may not be working in other parts of the health care system and why, and how to improve it. ED Utilization Project 3

Potentially avoidable ED visits ages 18-64, per 1,000 employer coverage enrollees. Potentially avoidable emergency department visits among adults ages 18-64 with employer-sponsored insurance per 1,000 enrollees. Switch Performance Areas. Select A Performance Area. Access to Health Care. Children.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) developed the Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Scorecard to improve transparency and accountability about the administration and outcomes of these programs. States and CMS can use the Medicaid and CHIP (MAC) Scorecard to drive improvements in areas such as state and ...

The overall emergency department (ED) visit rate was 43 visits per 100 people in 2021. ED visit rates were highest for infants under age 1 year (103 visits per 100 infants) and adults aged 75 and over (66 per 100 people). The ED visit rate for Black or African-American non-Hispanic people (81) was the highest among the selected

Metric is expressed as a rate per 1,000 denominator member months in the measurement year. Emergency department visits are defined by the following criteria: Claim or encounter is a hospital outpatient claim (claim type codes: 3, 26, 34) AND. One of more of the following criteria is met: Name. Value Set.

From 2018 to 2020, an average of 774,508 mental health-related ED visits occurred per year among adults in the United States, accounting for 12.3% of all ED visits made by adults. On average, 53.0 ED visits per 1,000 adults occurred per year in the United States in which any mental health disorder was diagnosed (Figure 1).

The overall emergency department (ED) visit rate was 40 visits per 100 people in 2020. The ED visit rate was highest for infants under age 1 year (68 visits per 100 infants), followed by adults aged 75 and over (63 per 100 people). The ED visit rate for non-Hispanic Black or African-American people (70 visits per 100 people) was highest