Athens Dark Tourism Guide 2023 (updated for 2024)

- Athens Blog

Travel insurance in 2024: Being safe while travelling to Athens (updated)

Η.Μ.S TRIUMPH Submarine found deep into the Aegean after 80 years

Table of contents

Introducing athens’ dark tourism scene, exploring the ruins and monuments of ancient greece.

- Taking in the Urban Legends of Athens' Streets

Penetrating the Mysterious Crypts of Athens

Seeking out the haunted houses in athens, notable dark tourism sites in athens, the athens war museum, overview and historical significance, notable exhibits and collections, visiting information, the kaisariani rifle range (skopeftirio), historical context, transformation into a memorial site, the 1941-1944 memorial site, the fascinating history of 4 korai street mansion, how to visit and what to expect, the athens polytechnic university, significance of the polytechnic uprising.

- Commemorative Events and the Gate's Symbolism

The Haidari Concentration Camp (Block 15)

Its history during world war ii, current status and the future as a museum, the parnitha sanatorium, origins and various uses throughout history, status as an abandoned site and visitor advice, the davelis cave, legends and history surrounding the cave, the cave as a natural and mythological point of interest, the first cemetery of athens, cemetery as a historic site and open-air museum, notable graves and examples of funerary art, sample itinerary for a dark tourist visit to athens.

Welcome to the ultimate dark tourism guide for Athens in 2023! Whether you’re a seasoned traveler looking for something a bit out of the ordinary, or an outsider curious about an ancient culture and its hidden secrets, this guide will provide all the information you need. From exploring long-forgotten mine shafts on world-renowned archaeological sites, to uncovering historically significant events in haunted cathedrals, get ready to explore some unforgettable experiences around Athens with our user-friendly google maps feature. Travelers can use this interactive map as they navigate their way through history while discovering exciting national monuments and iconic cultural hubs around town. Be warned though: there are arrows along the route that point towards places best left undiscovered due to their potentially spooky vibes so be sure not to click past them too quickly!

Welcome to Athens, a city rich in history and culture. While most visitors come to explore the ancient temples and marvel at the stunning architecture, there is another side to Athens that has been gaining popularity among tourists – its dark tourism scene. From the time of the Ottoman Empire to Greece's more recent economic crisis, Athens has experienced its fair share of dark and tragic events. And for those interested in exploring the city's haunting past, there are plenty of options to choose from. Take a tour of the infamous prison, where political dissidents were tortured during the military dictatorship or visit the site of a devastating terrorist attack that shook the city in 2003. While Athens' dark tourism scene may not be for everyone, it does offer a unique opportunity to explore the city's troubled, yet fascinating history.

Embark on a journey back in time to the ancient Greek civilization and explore the ruins and monuments that still stand tall today. From the iconic Parthenon in Athens to the impressive Temple of Zeus in Olympia, the architecture alone is awe-inspiring. But these structures are not just aesthetically pleasing - they are windows to the past, offering insight into the daily lives, myths, and beliefs of the ancient Greeks. Imagine walking along ancient roads, marveling at the intricate details of sculptures that have stood for millennia, and soaking in the rich history of this remarkable civilization. A visit to these ancient ruins and monuments is a must for any history buff or travel enthusiast.

Taking in the Urban Legends of Athens' Streets

As you wander the streets of Athens, you may begin to hear whispers of the city's urban legends. From the infamous "Melo-Katsourbos," a mischievous jester who reportedly haunts the streets of Monastiraki, to the eerie tales of the abandoned Psychiko Children's Hospital, there's no shortage of chilling stories to send shivers down your spine. But these legends aren't all frights and horrors. Some, like the story of the Beggar's Opera, offer a glimpse into the city's rich cultural history. So next time you're strolling through Athens, keep your ears open and see what stories you can uncover. Who knows what secrets and mysteries lurk just around the corner?

Welcome to Athens, a city steeped in mystery and history. As you wander through the bustling streets, it's hard not to feel in awe of the ancient wonders surrounding you. But if you're a true adventurer at heart, then you must venture underground to the mysterious crypts of Athens. Once used to house the remains of the dead, these crypts now hold centuries of secrets waiting to be discovered. Imagine walking through narrow passageways, surrounded by cold stone walls and dimly lit torches, feeling the weight of history bearing down on you. With every step, you'll uncover new clues to the past, from ancient hieroglyphics to hidden treasures. So grab your flashlight, and let's journey into the heart of Athens' intriguing past!

Athens, the historic capital of Greece, is a city rich in ancient myths and legends. If you're seeking an adrenaline rush and spine-tingling adventure, Athens is home to a plethora of haunted houses that are sure to give you goosebumps. From the eerie and abandoned mansion on Kifissia Avenue to the notorious Tower of the Winds, said to be home to the powerful wind daemon Boreas, there is an abundance of spooky spots to explore. Brave souls seeking something truly out of the ordinary can even visit the abandoned underground catacombs beneath the city, where ghosts of ancient Greeks are said to roam. So, book your tickets, pack your bags, and get ready to embark on an unforgettable ghost-hunting adventure in Athens.

Nestled in the heart of the city, the Athens War Museum stands as a sentinel to Greece's storied past. Established in 1975, its architectural grandeur hints at the treasures within, encapsulating the valor and sacrifice of Greek soldiers. The museum holds paramount significance in illustrating the city's role as a battleground in various conflicts.

The museum boasts a staggering collection of over 20,000 artifacts, each telling its own tale of heroism and hardship. Visitors encounter everything from antiquated weaponry from the Greco-Persian Wars to contemporary military technology. Notable exhibits include an Avro Anson plane, used during the Nazi occupation, and a fascinating array of uniforms worn by Greek soldiers throughout history.

Opening its gates from Monday to Sunday, the museum invites you to traverse through time from 09:00 to 17:00. Reaching the site is convenient, with several public transport links available. Admission costs start from 6 euros for adults, making it a must-see destination for any history enthusiast visiting Athens.

A mere whisper among locals not long ago, the Kaisariani Rifle Range has emerged as a monument to courage and resistance. It was here, in the grim days of May 1944, that the Nazi Occupation Forces executed 200 Greek partisans, etching a somber chapter in Athens' history.

Today, the rifle range is a testimony to the indomitable spirit of Greek resistance. Local authorities have meticulously transformed the once-forbidding grounds into a tranquil memorial site. Visitors can pay their respects at this hallowed ground and reflect upon the sacrifices made for freedom.

The story of the 4 Korai Street Mansion is one of resilience and remembrance. A mundane building took on a cloak of darkness during the WWII occupation, sheltering the Kommandantur—infamous for its role in detention and governance under Axis control. In the subterranean cells, countless tales of defiance and survival were etched into the walls by the imprisoned, a solemn yet powerful record.

Immersive and memorable, a visit here is a reverent experience. The remnants of wartime detention facilities offer a chilling reminder of those tumultuous times. Given the restored nature of the space, visitors walk in the shoes of the prisoners, experiencing the stark reality that no history book can fully convey.

The Athens Polytechnic Uprising of 1973 epitomizes the struggle for democracy and truth. When an autocratic junta stifled civil liberties, the resounding call for freedom echoed through the university's halls, a call that was met with fatal force.

Commemorative Events and the Gate's Symbolism

Today, the Polytechnic still hosts events to commemorate the uprising, keeping its memory alive. The charred remains of the university gate, breached by a tank in a fateful clash between the youth and the junta, remain untouched. It stands as a permanent testament to the power of protest and the perils that come with it.

A hushed visitation amidst the tranquil suburb of Haidari reveals the stark contrast of war's horrors. Block 15, a part of the Haidari Concentration Camp, saw the detention and torture of Greek citizens by the Nazi regime. Today, it serves as a vital archival and research center dedicated to preserving the memory of those who endured the camps' injustices.

Efforts are underway to transform this site into a museum, ensuring that the lessons from history remain relevant in contemporary discourse. By shedding light on the excesses of totalitarian regimes, visitors will gain a profound understanding of the perils of prejudice and aggression.

Nestled upon Mount Parnitha's verdant slopes, the Parnitha Sanatorium once offered a sanctuary for tuberculosis patients. Converted into an emergency hospital during World War II, it witnessed the struggles of the wounded, serving as a canvas for tales of perseverance and hope.

The site now lies abandoned, a haunting reminder of the past. As such, it provides a unique opportunity for contemplation. Visitors are advised to approach the sanatorium with respect for its history. The dilapidated structures and eerie silence serve as a poignant backdrop for reflections on the passage of time and the endurance of the human spirit.

The Davelis Cave, steeped in myth and historical intrigue, is a natural formation that has been the subject of many a tale. Home to a variety of fascinatingly eerie formations, the cave's depths conceal secrets that invite intrepid explorers to unravel the mysteries within.

It serves as a natural and mythological point of interest in the region. The cave's geological features, including spectacular stalactites and stalagmites, offer a sensory adventure through time. As you venture deeper, the cave's resonance with history and myth becomes palpable, making for an enthralling experience.

The First Cemetery of Athens exists not only as a resting place for the departed but also as an open-air museum. The grandeur of its ornate tombs and the illustrious figures interred within its hallowed grounds provide a unique reflection on the city's cultural and political history.

Notable figures from the annals of Greek history find their final repose here. The cemetery's diverse array of sculptures and funerary art styles is a tapestry of artistic expression. A stroll through these avenues is akin to a guided tour through the milestones of Greek society, revealing narratives often untold.

Athens is a city steeped in history, and for dark tourists, there are many compelling destinations that explore the darker side of this ancient city. Start your day by visiting the eerie Kokkinia execution site, where over 200 prisoners were executed during the Greek Civil War. Next, head to the controversial Museum of Anti-Dictatorial and Revolutionary Art, which houses a collection of artifacts from Greece's turbulent history. In the afternoon, explore the Athens War Museum, which boasts a vast collection of military memorabilia, including tanks and fighter jets. End the day with a trip to the ancient Kerameikos Cemetery, the final resting place for notable Athenians of the past. As a dark tourist, Athens offers a unique perspective to those seeking an unconventional travel experience.

Athens is the perfect destination for any dark tourist looking to experience an abundance of mystery, creepy vibes and a mystery deep-rooted in history. Visitors can explore ancient ruins, uncover old legends, enter crypts and buildings with secrets locked deep inside. Even the local cuisine has added flavor derived from centuries-old folk recipes. If you are looking to embark on a journey through time, then be sure to make Athens your next stop where you can reconnect with the city's darkness of the past. So make sure to check out our sample itinerary if you're brave enough to take on a daring dark tour in Athens!

Last updated on February 25th, 2024 at 08:38 am

Related posts

The religion of the city and the importance of the acropolis in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greek Diet, the Guide

The Cultural Debate Around Marina Satti’s “Zari” and Modern Greek Society

- dark tourism

- Andaman & Nicobar

- Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Channel Islands

- Cyprus (North)

- Czech Republic

- Dominican Republic

- Easter Island

- El Salvador

- Falkland Islands

- French Guiana

- Great Britain

- [Nagorno-Karabakh]

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Northern Ireland

- North Korea

- Philippines

- South Africa

- South Georgia

- South Korea

- Switzerland

- Transnistria

- Tristan da Cunha

- Turkmenistan

- disclaimer & privacy policy

© dark-tourism.com, Peter Hohenhaus 2009-2024

EXPERIENCES

A chilling journey of ‘dark tourism’ around greece.

Unearthing sites suffused with history's melancholy tones, certain to ignite intrigue among visitors

BY GIANNIS KOUTROUDIS

Translated by sophia velopoulos, published 02 june 2023, the sanctuary of the great gods on samothrace/photo: shutterstock.

We will navigate the labyrinth of “dark tourism.” A curious phenomenon has taken root in recent years – travellers are increasingly drawn towards narratives etched in shadow rather than the typical sun-soaked experiences. Thus, the rise of “dark tourism”, a global movement transforming travel into an exploration of humanity’s grim past. Morose? Possibly. Controversial? Certainly. But undeniably, dark tourism plays a pivotal role in preserving our historical memory, breathing life into narratives long obscured by time’s relentless march.

In this spirit, we present a selection of Greece’s most notorious dark tourism destinations, offering a distinct travel experience for those desiring a taste of the unconventional.

Spinalonga, Crete

Consider Spinalonga, Crete, an island of barely 100 square metres . Yet its history looms large, a colossal monument to human suffering. In 1903 , this abandoned Venetian fortress morphed into a leper colony , a place of exile for those afflicted with this incurable disease.

Dark, isn’t it? But there’s more. The notoriety of Spinalonga grew so profound that patients across Europe found themselves bound for this tiny enclave. With no cure for leprosy available, Spinalonga became a one-way journey, a farewell to freedom, to life itself.

Spinalonga/Photo: Unsplash

Despite these grim realities, Spinalonga didn’t surrender to despair. It blossomed into a vibrant community, connected to Plaka by the ceaseless rhythm of the sea. Its residents, during the German Occupation , launched a unique rebellion, leveraging the occupiers’ inherent fear to secure free ally radios . A daring defiance of authority in a place where normalcy had long ceased to exist.

Photo: Unsplash

Spinalonga/Photo: Kanella Klimatsida/Eurokinissi

With the advent of effective antibiotics , Spinalonga’s story started drawing to a close. This once bustling island slowly deflated, only to be reclaimed by silence. Yet, in a twist of fate, this once-doomed rock has become one of Crete’s most frequented dark tourism hotspots. Its tragic history now casting a hauntingly beautiful glow.

Photo: Shutterstock

Sanctuary of the Great Gods/Photo: Panagiotis Savvidis

Replica of the Winged Victory of Samothrace/Photo: Panagiotis Savvidis

Sanctuary of the great gods, samothrace.

Venture into the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace. Though now a serene archaeological site, it’s among the most enigmatic monuments in Greece. The site is entangled with the Kabeirian Mysteries, ancient rites venerating chthonic deities unfamiliar in mainland Greece.

At this sanctuary, Zeus , Hera , and Aphrodite were overlooked. Instead, aristocrats and slaves alike participated in secretive ceremonies, offering cryptic sacrifices to honour deities that remain, to this day, elusive to researchers.

Current findings suggest the Kabeirian Mysteries originated from ancient Anatolian religions, which found their way to Samothrace for reasons obscured by time. Legend has it, the site’s aura was so powerful that any uninitiated individual who dared to enter would invite grave misfortune, some said they would be cursed for life. Pay a visit to Samothrace and attempt to untangle this ancient enigma. Perhaps you’ll be the one to decode its mysteries.

Δείτε αυτή τη δημοσίευση στο Instagram. Η δημοσίευση κοινοποιήθηκε από το χρήστη John Xenos (@giannhs_xenos)

War Museum of Leros

Among the murkier recesses of the Leros tunnel, one can glimpse relics of a bleaker past: Fascist Italy’s symbology, Nazi Germany’s anti-asphyxiation suits, helmets peppered with bullet holes, and even submarine torpedoes, all displayed with a certain morose pride.

Δείτε αυτή τη δημοσίευση στο Instagram. Η δημοσίευση κοινοποιήθηκε από το χρήστη Іван Олександрович Каберне (@ivankaberne)

This tunnel bore witness to the Battle of Leros, where Fascist Italy’s forces bit, scratched, and clawed to retain one of their last territories in the Eastern Mediterranean. A visit, is guaranteed to send shivers down your spine. You’ll be handed a shot-sized, yet potent taste of the horrors from humanity’s darkest war in recent history.

Dragon Houses of Southern Euboea/Photo: Shutterstock

Dragon Houses of Southern Euboea/Evia

Next, let’s explore the enigmatic Dragon Houses of Southern Euboea. Only 25 of these enigmatic structures exist, and their purpose remains a riddle. Were they homes, places for exiles, or temples? We’re not certain. Constructed in the early Hellenistic period, these Dragon Houses are monolithic stone structures set at dominating locations.

These edifices, made of enormous grey stones, were presumably built by individuals with Herculean strength. With no definitive findings in the area, it’s almost as if these houses sprang from the earth. Surely, a tale that’d set your ‘dark intrigue’ alarm ringing.

So, if you’re eager to uncover the secrets of the Dragon Houses, all you need is a comfortable pair of shoes and an appetite for mystery. And remember, if you manage to solve this enigma, do share your revelation. We’d all love to delve deeper into the true purpose of these mysterious structures.

Medieval castles and peculiar Dragon houses in a charming destination in Greece

Eastern Crete’s Charm: History, Luxury and Authenticity

Mystic Samothrace – Extreme activities for adventure seekers

RELATED ARTICLES

Your Guide to the Cyclades

UNKNOWN GREECE

The hidden monasteries of mt grammos.

ARTS & CULTURE

May day in greece: flowers, community and tradition.

The Island-Hopping Series: Naxos – Paros – Antiparos

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

‘Red lights are flashing’: Athens tourism explosion threatens ancient sites

Visitor numbers to hit 30m – three times nation’s population – as experts grapple to balance economic gains with conservation

H ordes of tourists huddle in groups along the cobbled boulevard beneath the Acropolis on a late November morning more summery than autumnal. Others get on and off the open-top doubledeckers running the riviera route. A man dressed as an ancient Marathon warrior poses “for a fee” with the majestic citadel in the background.

“We’re having a great year,” says the Greek tourism minister, Vassilis Kikilias. “It’s almost December and the season is still going which is exactly what we want – to extend it, bit by bit.”

Tourism in Athens – as Greece at large – has defied all expectation. The sector, the country’s economic engine, was budgeted to bring in €15bn this year and appeared doomed when bookings froze in February at the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Instead, earnings are more likely to exceed €18bn with visitor numbers poised to come close to 30 million – nearly three times the nation’s population – despite the war, absence of Chinese visitors and the unwanted appearance of jellyfish, says Kikilias.

At the height of the summer, about 16,000 holidaymakers each day were making the arduous climb up to the Acropolis. In the alleyways of Plaka, the neighbourhood beneath the ancient site, shopkeepers say they have never had it so good. “If anything, we just want them to go home now,” says Anna Simou, who works in a contemporary Greek design store in the district. “We’re all exhausted and that’s with management employing new staff.”

But the post-pandemic bounceback is not without risks. Kikilias is the first to say that the thriving industry needs to be spread more evenly beyond the “two and a half regions” drawing the crowds. Sustainability is also on the mind of Kostas Bakoyannis, the mayor of Athens, who last week called for a city tax to be placed on visitors to help cope with the surge in demand on services. In a departure from a time when the Greek capital was viewed invariably as a transit route to the islands, more than 7 million tourists are estimated to have descended on the metropolis in 2022.

“It’s unfair that 650,000 permanent residents in the heart of ancient Athens should foot the bill,” Bakoyannis says. “If we want to sustain the city we need to adapt in the way that almost every other European capital has, and introduce a city tax on visitors.”

Americans arriving on 63 direct flights a week have been key to making Greece the world’s third most popular tourist destination this year, according to industry figures. But as officials tally the success of a sector that accounts for 25% of GDP, the spectre of overtourism – long evident on islands such as Santorini – has spurred concerns over the dangers soaring numbers pose for the conservation of cultural gems.

As home to 18 Unesco world heritage sites, Greece is increasingly highlighting the challenges of managing visitor numbers, with experts emphasising the fine balance that needs to be struck between protecting ancient monuments and developing them for touristic use. The 495–429BC Acropolis, which is among the designated sites, was itself at the centre of controversy when in 2020 the government installed concrete pathways around the Periclean masterpiece and an unsightly glass and steel lift financed by private donors to improve access.

“Reds lights are flashing,” says Peter DeBrine, Unesco’s leading tourism adviser.“We have to start asking how much is too much and 16,000 visitors clogging a monument like the Acropolis every day sounds like way too much.”

DeBrine said studies had shown that, more than ever, travellers wanted sustainable options.

With tourism roaring back in both Europe and the US, it was imperative, he said, that capacity measures were adopted at popular heritage sites.

“We have gone from overtourism to revenge tourism with the same net effect,” he told the Guardian, describing the latter as a pent-up response to the pandemic. “What is needed is a radically different approach which starts with consumers but extends to tourism and heritage management. It’s clear that authorities have to take measures to relieve overcrowding at world heritage sites if the tourism experience isn’t to be degraded and conservation ensured.”

Unesco’s 50th anniversary convention in Delphi debated the impacts of the climate crisis and overtourism. It has urged members to change marketing tactics by focusing on attracting fewer, high-spending and lower-impact tourists, rather than large groups.

“Our hope is that tickets will soon only be sold online because that would be a sure way of limiting access,” says DeBrine, adding that adjustment of ticket prices according to season could also be enforced with entrance fees costing more at the height of summer. “Choosing to travel during the low or shoulder season makes a huge impact.”

Heritage sites in east Asia recently began implementing a new Unesco visitor management and strategy tool to identify a baseline for sustainable tourism.

“It’s given us a snapshot,” explained DeBrine. “We realise tourism is the lifeblood for so many communities and vital to local economies but overtourism is a real danger. Either you’re clever and you take measures or you kill the goose that lay the golden egg.”

Most viewed

Exploring Life's Small Moments in a Vast World

The Ultimate Athens Dark Tourism Guide (Updated 2024)

When we think of Athens, our minds race to images of ancient ruins, golden beaches, and traditional tavernas. But there's a darker, more enigmatic side to this ancient city - a side that even I, as a local, was unaware of for most of my life. This is the world of dark tourism and, in Athens, it has a deep story to tell. This guide is a local's effort to gather all the most important dark tourism spots in Athens, Greece. It is updated for 2023 and, as new spots are discovered, it will be updated.

Exploring Tskaltubo: A Soviet Ghost Town of Abandoned Sanatoriums

Time stands still in Tskaltubo, where the once thriving Soviet spa and resort town has started to slowly be reclaimed by nature. This, however, has led this picturesque Georgian town to become a prominent destination for urban explorers and dark tourism enthusiasts. In this guide, you will find everything you need to know about visiting the most famous abandoned Sanatoriums of Tskaltubo.

Athens Dark Tourism Spot: Exploring A Nazi Torture Site

How well do we know our hometown? Living in Athens all my life, I thought I knew most tourist posts. I was shocked when I found that an Athens dark tourism spot was in the city's center. A place Nazis used to imprison and torture people during the German occupation. I am speaking about the "1941-1944 Memorial Site", the place of the former Kommandatur.

Tourism’s dark side: Are those who love Greece killing it?

Average Greek property prices increased by 12 percent last year and are set to increase by another 14 percent this year, according to Bank of Greece data.

Athens, Greece – Shortly after the conservative New Democracy party came to power in Greece in 2019, computer scientist Nikos Larisis left his job in the Netherlands and repatriated to the Mediterranean country for a salary worth a third of the 9,000 euros ($9,500) he was making per month.

He appeared to vindicate New Democracy’s pledge to bring back about half a million educated young workers who had fled the country’s economic depression from 2010 to 2018.

Keep reading

‘without rules we cannot live’: greece seeks ways to tackle ‘overtourism’, after slew of disasters, greeks wonder what is happening to their democracy, an ex-goldman sachs banker vies to preside over the troubled greek left.

The conservatives returned to power for a second term in June with little evidence that many Greeks had followed in Larisis’s footsteps.

Even he and his fiancee, Eleftheria Tsiartsiani, a public elementary schoolteacher, had been feeling stuck and were considering going abroad.

They were paying a quarter of their joint income in rent and could not borrow enough money to buy the two-bedroom home in which they dreamed of starting their family.

Then the government announced a 1.8-billion-euro ($1.9bn) programme to help young couples buy their first home.

“Eleftheria told me, ‘Niko, we can buy a home. We can reconsider. We needn’t pick up stakes and leave,'” Larisis told Al Jazeera.

But after looking into the government’s offer, called My Home, the couple became disillusioned.

“It wasn’t designed well at all. It led people on and destroyed their dreams,” Larisis said.

Larisis and Tsiartsiani could borrow 90,000 euros ($96,000) under the programme, but that did not secure an attractive family home in a market geared towards foreign buyers spending 250,000 euros ($270,000) for a Golden Visa, which at the time offered them five years of legal residence and a path to citizenship. The spending requirement for the Golden Visa has since changed to double that amount.

“I’m going to let the state keep its 90,000 euros,” Tsiartsiani said. “There’s no point in buying a small, old apartment, dark and dank, that doesn’t fit our needs, smelling of mould in an unkempt building and being in debt up to my neck for the rest of my life.”

Moreover, Tsiartsiani said: “We saw a lot of sales ads that stipulated, ‘The property isn’t for sale through the My Home programme.'”

Sellers told the couple they did not believe they would get their money from the government and wanted cash only.

The experience convinced the couple that Greek law was tilted in favour of non-Greeks.

My Home did not allow beneficiaries to rent out their property and restricted them to buying a property close to work. The Golden Visa programme has no such limitations.

“There’s a big party going on. Foreign capital is trying to take advantage of the situation here, and the laws are helping them. Golden Visas allow people to come and buy homes here … while others are struggling with loans they can’t repay,” Larisis said.

The sting in tourism’s tail

Greece’s big economic success under New Democracy has been tourism, which has boomed since the COVID-19 pandemic, attracting three times Greece’s population each year. It brought in a near-record 18 billion euros ($19bn) in revenue last year.

Tourism helps bring in the foreign currency with which Greece services its loans, and it has helped existing homeowners. About 105,000 properties are now offered on short-term rentals through Airbnb.

But it has also worsened a demographic problem. By restoring real estate value lost during the depression, it has put first homes out of the reach of young people.

“We emerged from the pandemic with a bit of extra cash, … which was mainly concentrated on housing,” said real estate consultant Stelios Bouras, who runs the Greek Guru real estate news website. “Working at home, people wanted larger houses. … This coincided also with a massive increase in Greek homes going to foreign buyers.”

Average Greek property prices increased by 12 percent last year, and are set to increase by another 14 percent this year, according to Bank of Greece data.

That has spurred investment in real estate, but almost all of it is geared towards the top end of the market.

The Ellinikon is a prime example – a 600-hectare (1,500-acre) urban redevelopment of what used to be the Athens airport, nestled among the city’s southern suburbs.

Its first project, Marina Tower, now rising along the Attica shore, will be Greece’s tallest building when it is finished.

It will also be one of the most expensive. Every floor has been sold at a reputed 16,000 euros ($17,000) per square metre (nearly 11sq ft).

The Ellinikon’s owners said real estate will average 10,000 euros ($10,600) per square metre, but that is still well above the capabilities of most Greeks.

“The growth in the market which everyone is citing right now in terms of investment is for your high net worth individual from abroad and your top income level in Greece,” Bouras told Al Jazeera.

“For the vast majority, there is zero development. And if you look at government policy to increase supply levels, there is almost no movement,” he added.

The Ellinikon’s CEO makes no apology for the fact that 30 percent of the 1.2 billion euros ($1.27bn) of real estate he has already sold has gone to Syrians, Egyptians, Emiratis, other Europeans and Americans.

Odysseas Athanasiou argued that by attracting foreign buyers, The Ellinikon opens up Greece’s stagnant economy.

“For many, many decades, Greece was redistributing the pie of wealth, or poverty, if you will, and now with the new income that is coming from all places in the world, we are bringing in new money. The new money will be distributed more or less to everybody,” Athanasiou told Al Jazeera.

Among other benefits, Athanasiou says, The Ellinikon will create 80,000 permanent jobs.

Shrinking, ageing population

Greek society faces a potentially existential problem, and property prices are making it worse.

Its population has been shrinking since the turn of the century. That shrinkage accelerated after its eurozone partners imposed austerity policies on it in return for emergency loans in 2010.

Greece’s birth rate fell by 30 percent from 2011 to 2021 to under 84,000 per year, slipping ever-further below the death rate, according to the Hellenic Statistical Service.

The cumulative population loss during that decade was 329,451, which roughly tallies with the 2021 census recording a 3.1 percent population drop.

Given that each Greek paid on average 5,758 euros ($6,125) in taxes and social security contributions last year, this drop represents a loss of nearly 2 billion euros ($2.13bn) a year in state revenue – about 3.2 percent – over the long term.

Analysts said that by mid-century, Greece could find it difficult to generate the current level of state revenue – 60 billion euros last year ($64bn) – or man its armed forces.

The population drop is especially damaging in combination with ageing. Only 4.2 million Greeks work, supporting a total population of 10.5 million, including three million pensioners.

New Democracy has begun Greece’s first capitalised social security scheme for the under 25s, but for now, the majority of pensioners relies on current contributions.

New Democracy has also launched a series of measures to tackle the population decline and may have had a measure of success.

It delivered on promises to reduce the income tax, sales tax and social security contributions and offered paternity leave and extended daycare.

It offered a 2,000-euro ($2,200) cash handout per child, raised the tax rebate for families by 1,000 euros ($1,065) and now promises to drive up average salaries from 1,170 to 1,500 euros ($1,245 to $1,600).

Signs of improvement

Greece may have begun to see a faint heartbeat of improvement. Live births increased by 1.2 percent in 2020 and by 0.7 percent in 2021.

But My Home, its biggest direct measure to help young couples move ahead with their lives, has met with mixed results.

The programme was meant to accommodate 137,000 young people, but only 4,500 applications have received state approval and not all of them have gone on to receive bank approval.

“All programmes undergo evaluation and correction,” Maria Syrregela, deputy labour minister under the previous government told Al Jazeera. “My Home was the start of an ongoing state programme to provide housing.”

Syrregela was in charge of demographic policy, and perhaps her biggest achievement was that she got the opposition to sign onto a multiyear plan of action.

“Demographic policy isn’t about doing something today and having tangible results tomorrow,” she said.

“If you start a programme now, you might see results in 10 years. That’s why governments tended not to bother.”

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Beaches? Cruises? ‘Dark’ Tourists Prefer the Gloomy and Macabre

Travelers who use their off time to visit places like the Chernobyl nuclear plant or current conflict zones say they no longer want a sanitized version of a troubled world.

By Maria Cramer

North Korea. East Timor. Nagorno-Karabakh, a mountainous enclave that for decades has been a tinderbox for ethnic conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis.

They’re not your typical top tourist destinations.

But don’t tell that to Erik Faarlund, the editor of a photography website from Norway, who has visited all three. His next “dream” trip is to tour San Fernando in the Philippines around Easter , when people volunteer to be nailed to a cross to commemorate the suffering of Jesus Christ, a practice discouraged by the Catholic Church.

Mr. Faarlund, whose wife prefers sunning on Mediterranean beaches, said he often travels alone.

“She wonders why on earth I want to go to these places, and I wonder why on earth she goes to the places she goes to,” he said.

Mr. Faarlund, 52, has visited places that fall under a category of travel known as dark tourism , an all-encompassing term that boils down to visiting places associated with death, tragedy and the macabre.

As travel opens up, most people are using their vacation time for the typical goals: to escape reality, relax and recharge. Not so dark tourists, who use their vacation time to plunge deeper into the bleak, even violent corners of the world.

They say going to abandoned nuclear plants or countries where genocides took place is a way to understand the harsh realities of current political turmoil, climate calamities, war and the growing threat of authoritarianism.

“When the whole world is on fire and flooded and no one can afford their energy bills, lying on a beach at a five-star resort feels embarrassing,” said Jodie Joyce, who handles contracts for a genome sequencing company in England and has visited Chernobyl and North Korea .

Mr. Faarlund, who does not see his travels as dark tourism, said he wants to visit places “that function totally differently from the way things are run at home.”

Whatever their motivations, Mr. Faarlund and Ms. Joyce are hardly alone.

Eighty-two percent of American travelers said they have visited at least one dark tourism destination in their lifetime, according to a study published in September by Passport-photo.online, which surveyed more than 900 people. More than half of those surveyed said they preferred visiting “active” or former war zones. About 30 percent said that once the war in Ukraine ends, they wanted to visit the Azovstal steel plant, where Ukrainian soldiers resisted Russian forces for months .

The growing popularity of dark tourism suggests more and more people are resisting vacations that promise escapism, choosing instead to witness firsthand the sites of suffering they have only read about, said Gareth Johnson, a founder of Young Pioneer Tours , which organized trips for Ms. Joyce and Mr. Faarlund.

Tourists, he said, are tired of “getting a sanitized version of the world.”

A pastime that goes back to Gladiator Days

The term “dark tourism” was coined in 1996, by two academics from Scotland, J. John Lennon and Malcolm Foley, who wrote “Dark Tourism: The Attraction to Death and Disaster.”

But people have used their leisure time to witness horror for hundreds of years, said Craig Wight, associate professor of tourism management at Edinburgh Napier University.

“It goes back to the gladiator battles” of ancient Rome, he said. “People coming to watch public hangings. You had tourists sitting comfortably in carriages watching the Battle of Waterloo.”

Professor Wight said the modern dark tourist usually goes to a site defined by tragedy to make a connection to the place, a feeling that is difficult to achieve by just reading about it.

By that definition, anyone can be a dark tourist. A tourist who takes a weekend trip to New York City may visit Ground Zero. Visitors to Boston may drive north to Salem to learn more about the persecution of people accused of witchcraft in the 17th century. Travelers to Germany or Poland might visit a concentration camp. They might have any number of motivations, from honoring victims of genocide to getting a better understanding of history. But in general, a dark tourist is someone who makes a habit of seeking out places that are either tragic, morbid or even dangerous, whether the destinations are local or as far away as Chernobyl.

In recent years, as tour operators have sprung up worldwide promising deep dives into places known for recent tragedy, media attention has followed and so have questions about the intentions of visitors, said Dorina-Maria Buda, a professor of tourism studies at Nottingham Trent University .

Stories of people gawking at neighborhoods in New Orleans destroyed by Hurricane Katrina or posing for selfies at Dachau led to disgust and outrage .

Were people driven to visit these sites out of a “sense of voyeurism or is it a sense of sharing in the pain and showing support?” Professor Buda said.

Most dark tourists are not voyeurs who pose for photos at Auschwitz, said Sian Staudinger, who runs the Austria-based Dark Tourist Trips , which organizes itineraries in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe and instructs travelers to follow rules like “NO SELFIES!”

“Dark tourists in general ask meaningful questions,” Ms. Staudinger said. “They don’t talk too loud. They don’t laugh. They’re not taking photos at a concentration camp.”

‘Ethically murky territory’

David Farrier , a journalist from New Zealand, spent a year documenting travels to places like Aokigahara , the so-called suicide forest in Japan, the luxury prison Pablo Escobar built for himself in Colombia and McKamey Manor in Tennessee, a notorious haunted house tour where people sign up to be buried alive, submerged in cold water until they feel like they will drown and beaten.

The journey was turned into a show, “Dark Tourist,” that streamed on Netflix in 2018 and was derided by some critics as ghoulish and “sordid.”

Mr. Farrier, 39, said he often questioned the moral implications of his trips.

“It’s very ethically murky territory,” Mr. Farrier said.

But it felt worthwhile to “roll the cameras” on places and rituals that most people want to know about but will never experience, he said.

Visiting places where terrible events unfolded was humbling and helped him confront his fear of death.

He said he felt privileged to have visited most of the places he saw, except McKamey Manor.

“That was deranged,” Mr. Farrier said.

Professor Buda said dark tourists she has interviewed have described feelings of shock and fear at seeing armed soldiers on streets of countries where there is ongoing conflict or that are run by dictatorships.

“When you’re part of a society that is by and large stable and you’ve gotten into an established routine, travel to these places leads you to sort of feel alive,” she said.

But that travel can present real danger.

In 2015, Otto Warmbier , a 21-year-old student from Ohio who traveled with Young Pioneer Tours, was arrested in North Korea after he was accused of stealing a poster off a hotel wall. He was detained for 17 months and was comatose when he was released. He died in 2017, six days after he was brought back to the United States.

The North Korean government said Mr. Warmbier died of botulism but his family said his brain was damaged after he was tortured.

Americans can no longer travel to North Korea unless their passports are validated by the State Department.

A chance to reflect

Even ghost tours — the lighter side of dark tourism — can present dilemmas for tour operators, said Andrea Janes, the owner and founder of Boroughs of the Dead: Macabre New York City Walking Tours.

In 2021, she and her staff questioned whether to restart tours so soon after the pandemic in a city where refrigerated trucks serving as makeshift morgues sat in a marine terminal for months.

They reopened and were surprised when tours booked up fast. People were particularly eager to hear the ghost stories of Roosevelt Island, the site of a shuttered 19th-century hospital where smallpox patients were treated .

“We should have seen as historians that people would want to talk about death in a time of plague,” Ms. Janes said.

Kathy Biehl, who lives in Jefferson Township, N.J., and has gone on a dozen ghost tours with Ms. Janes’s company, recalled taking the tour “Ghosts of the Titanic” along the Hudson River. It was around 2017, when headlines were dominated by President Trump’s tough stance on refugees and immigrants coming into the United States.

Those stories seemed to dovetail with the 100-year-old tales of immigrants trying to make it to New York on a doomed ship, Ms. Biehl said.

It led to “a catharsis” for many on the tour, she said. “People were on the verge of tears over immigration.”

Part of the appeal of dark tourism is its ability to help people process what is happening “as the world gets darker and gloomier,” said Jeffrey S. Podoshen , a professor of marketing at Franklin and Marshall College, who specializes in dark tourism.

“People are trying to understand dark things, trying to understand things like the realities of death, dying and violence,” he said. “They look at this type of tourism as a way to prepare themselves.”

Mr. Faarlund, the photo editor, recalled one trip with his wife and twin sons: a private tour of Cambodia that included a visit to the Killing Fields , where between 1975 and 1979 more than 2 million Cambodians were killed or died of starvation and disease under the Khmer Rouge regime.

His boys, then 14, listened intently to unsparing and brutal stories of the torture center run by the Khmer Rouge. At one point, the boys had to go outside, where they sat quietly for a long time.

“They needed a break,” Mr. Faarlund said. “It was quite mature of them.”

Afterward, they met two of the survivors of the Khmer Rouge, fragile men in their 80s and 90s. The teenagers asked if they could hug them and the men obliged, Mr. Faarlund said.

It was a moving trip that also included visits to temples, among them Angkor Wat in Siem Reap, and meals of frog, oysters and squid at a roadside restaurant.

“They loved it,” Mr. Faarlund said of his family.

Still, he can’t see them coming with him to see people re-enact the crucifixion in the Philippines.

“I don’t think they want to go with me on that one,” Mr. Faarlund said.

52 Places for a Changed World

The 2022 list highlights places around the globe where travelers can be part of the solution.

Follow New York Times Travel on Instagram , Twitter and Facebook . And sign up for our weekly Travel Dispatch newsletter to receive expert tips on traveling smarter and inspiration for your next vacation. Dreaming up a future getaway or just armchair traveling? Check out our 52 Places for a Changed World for 2022.

Maria Cramer is a reporter on the Travel desk. Please send her tips, questions and complaints about traveling, especially on cruises. More about Maria Cramer

Open Up Your World

Considering a trip, or just some armchair traveling here are some ideas..

52 Places: Why do we travel? For food, culture, adventure, natural beauty? Our 2024 list has all those elements, and more .

Mumbai: Spend 36 hours in this fast-changing Indian city by exploring ancient caves, catching a concert in a former textile mill and feasting on mangoes.

Kyoto: The Japanese city’s dry gardens offer spots for quiet contemplation in an increasingly overtouristed destination.

Iceland: The country markets itself as a destination to see the northern lights. But they can be elusive, as one writer recently found .

Texas: Canoeing the Rio Grande near Big Bend National Park can be magical. But as the river dries, it’s getting harder to find where a boat will actually float .

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

Dark tourism: when tragedy meets tourism

The likes of Auschwitz, Ground Zero and Chernobyl are seeing increasing numbers of visitors, sparking the term 'dark tourism'. But is it voyeuristic or educational?

Days after 71 people died in a London tower block fire last June, something strange started to happen in the streets around it. Posters, hastily drawn by members of the grieving community of Grenfell Tower, appeared on fences and lamp posts in view of the building's blackened husk.

'Grenfell: A Tragedy Not A Tourist Attraction,' one read, adding — sarcastically — a hashtag and the word 'selfies'. As families still searched for missing inhabitants of the 24-storey block, and the political shock waves were being felt through the capital, people had started to arrive in North Kensington to take photos. Some were posing in selfie mode.

"It's not the Eiffel Tower," one resident told the BBC after the posters attracted the attention of the press. "You don't take a picture." Weeks later, local people were dismayed when a coachload of Chinese tourists pulled up nearby so that its occupants could get out and take photos.

Grenfell Tower, which still dominates the surrounding skyline (it's due to be demolished in late 2018), had become a site for 'dark tourism', a loose label for any sort of tourism that involves visiting places that owe their notoriety to death, disaster, an atrocity or what can also loosely be termed 'difficult heritage'.

It's a phenomenon that's on the rise as established sites such as Auschwitz and the September 11 museum in Manhattan enjoy record visitor numbers. Meanwhile, demand is rising among those more intrepid dark tourists who want to venture to the fallout zones of Chernobyl and Fukushima, as well as North Korea and Rwanda. In Sulawesi, Indonesia, Western tourists wielding GoPros pay to watch elaborate funeral ceremonies in the Toraja region, swapping notes afterwards on TripAdvisor.

Along the increasingly crowded dark-tourist trail, academics, tour operators and the residents of many destinations are asking searching questions about the ethics of modern tourism in an age of the selfie and the Instagram hashtag. When Pompeii, a dark tourist site long before the phrase existed, found itself on the Grand Tour of young European nobility in the 18th century, dozens of visitors scratched their names into its excavated walls. Now we leave our mark in different ways, but where should we draw the boundaries?

Questions like these have become the life's work of Dr Philip Stone , perhaps the world's leading academic expert on dark tourism. He has a background in business and marketing, and once managed a holiday camp in Scotland. But a fascination with societal attitudes to mortality led to a PhD in thanatology, the study of death, and a focus on tourism.

"I'm not even a person who enjoys going to these places," Stone says from the University of Central Lancashire, where he runs the Institute for Dark Tourism Research. "But what I am interested in is the way people face their own mortality by looking at other deaths of significance. Because we've become quite divorced from death yet we have this kind of packaging up of mortality in the visit economy which combines business, sociology, psychology under the banner of dark tourism. It's really fascinating to shine a light on that."

Historical roots

The term 'dark tourism' is far newer than the practice, which long predates Pompeii's emergence as a morbid attraction. Stone considers the Roman Colosseum to be one of the first dark tourist sites, where people travelled long distances to watch death as sport. Later, until the late 18th century, the appeal was starker still in central London, where people paid money to sit in grandstands to watch mass executions. Hawkers would sell pies at the site, which was roughly where Marble Arch stands today.

It was only in 1996 that 'dark tourism' entered the scholarly lexicon when two academics in Glasgow applied it while looking at sites associated with the assassination of JFK. Those who study dark tourism identify plenty of reasons for the growing phenomenon, including raised awareness of it as an identifiable thing. Access to sites has also improved with the advent of cheap air travel. It's hard to imagine that the Auschwitz-Birkenau memorial and museum would now welcome more than two million visitors a year (an average of almost 5,500 a day, more than two-thirds of whom travel to the Polish site from other countries in Europe) were it not for its proximity to Krakow's international airport.

Peter Hohenhaus, a widely travelled dark tourist based in Vienna, also points to the broader rise in off-the-beaten track tourism, beyond the territory of popular guidebooks and TripAdvisor rankings. "A lot of people don't want mainstream tourism and that often means engaging with places that have a more recent history than, say, a Roman ruin," he says. "You go to Sarajevo and most people remember the war being in the news so it feels closer to one's own biography."

Hohenhaus is also a fan of 'beauty in decay', the contemporary cultural movement in which urban ruins have become subject matter for expensive coffee-table books and a thousand Instagram accounts. The crossover with death is clear. "I've always been drawn to derelict things," the 54-year-old says. As a child in Hamburg, he would wonder at the destruction of war still visible around the city's harbour.

That childhood interest has developed into an obsession; Hohenhaus has visited 650 dark tourist sites in 90 countries, logging them all and more besides on his website . He has plans to put together the first dark tourism guidebook. His favourite holiday destination today is Chernobyl and its 'photogenic' ghost town. "You get to time travel back into the Soviet era but also into an apocalyptic future," he says. He also enjoys being emotionally challenged by these places. "I went to Treblinka in 2008 and heard the story of a teacher at an orphanage in Warsaw who was offered a chance to escape but refused and went with his children to the gas chambers. Stories like that are not everyday, you mull over them. Would you have done that?"

But while, like any tourism, dark tourism at its best is thought-provoking and educational, the example of Grenfell Tower hints at the unease felt at some sites about what can look like macabre voyeurism. "I remember the Lonely Planet Bluelist book had a chapter about dark tourism a while ago and one of the rules was 'don't go back too early'," Hohenhaus says. "But that's easier said than calculated. You have to be very aware of reactions and be discreet when you're not in a place with an entrance fee and a booklet." Hohenhaus said he had already thought about Grenfell Tower and admits he would be interested to see it up close. "It's big, it's dramatic, it's black and it's a story you've followed in the news," he says. "I can see the attraction. But I would not stand in the street taking a selfie."

A mirror to mortality

An urge to see and feel a place that has been reduced to disaster shorthand by months of media coverage is perhaps understandable, but Stone is most interested in the draw — conscious or otherwise — of destinations that hold up a mirror to our own mortality. "When we touch the memory of people who've gone what we're looking at is ourselves," he says. "That could have been us in that bombing or atrocity. We make relevant our own mortality." That process looks different across cultures — and generations — and Stone says we should take this into account before despairing of selfie takers at Grenfell Tower or Auschwitz.

"I've heard residents at Grenfell welcoming visitors because it keeps the disaster in the public realm, but they didn't like people taking photos because it's a visual reminder that you're a tourist and therefore somehow defunct of morality," he explains. "We're starting to look at selfies now. Are they selfish?" Stone argues that the language of social media means we no longer say "I was here", but "I am here — see me". He adds: "We live in a secular society where morality guidelines are increasingly blurred. It's easy for us to say that's right or wrong, but for many people it's not as simple as that."

"Travel itself is innately voyeuristic," argues Simon Cockerel, the general manager of Koryo Tours , a North Korea specialist based in Beijing. Cockerel, who has lived in China for 17 years and joined Koryo in 2002, says demand has grown dramatically for trips to Pyongyang and beyond, from 200 people a year in the mid 1990s, when the company started, to more than 5,000 more recently. He has visited the country more than 165 times and says some clients join his tours simply to bag another country, and some for bragging rights. But the majority have a genuine interest in discovering a country — and a people — beyond the headlines.

"I've found everyone who goes there to be sensitive and aware of the issues," he says. "The restrictions do create a framework for it to be a bit like a theme park visit but we work hard to blur those boundaries. More than 25 million people live in North Korea, and 24.99 million of them have nothing to do with what we read in the news and deserve to be seen as people not as zoo animals or lazy caricatures."

More challenging recently has been the US ban on its citizens going to North Korea, imposed last summer after the mysterious death of Otto Warmbier. The American student had been arrested in Pyongyang after being accused of trying to steal a propaganda poster. Americans made up about 20% of Koryo's business, but Cockerel argues the greater loss is to mutual perception in the countries. "The North Korean government represent Americans as literal wolves with sharpened nails," he says. "At least a few hundred Americans going there was a kind of bridgehead against that. Now that's gone."

At Grenfell Tower, responsible tourism may yet serve to keep alive the memory of the disaster, just as it does, after a dignified moratorium, at Auschwitz and the former Ground Zero. Hohenhaus says he will resist the urge to go until some sort of memorial is placed at the site of the tower. At around the time of a commemorative service at St Paul's Cathedral six months after the fire, there were calls for the site eventually to be turned into a memorial garden. The extent to which Hohenhaus and other dark tourists are welcomed will be decided by the people still living there.

Five of the world's dark tourism sites

1. North Korea Opened to visitors in the late 1980s, North Korea now attracts thousands of tourists each year for a peek behind the headlines.

2. Auschwitz-Birkenau The former Nazi death camp became a memorial in 1947 and a museum in 1955. It's grown since and in 2016 attracted a record two million visitors.

3. 9/11 Memorial and Museum Built in the crater left by the twin towers of the World Trade Center, the museum, opened in 2014, has won plaudits for its portrayal of a disaster and its impact.

4. Rwanda Visitor numbers to genocide memorials have grown in Cambodia and Bosnia as well as in Rwanda, where there are several sites dedicated to the 1994 massacre of up to a million people. The skulls of victims are displayed.

5. Chernobyl & Pripyat, Ukraine Several tour companies exist to send visitors to the exclusion zone and ghost town left otherwise empty after the nuclear accident in 1986. All are scanned for radiation as they leave.

Published in the March 2018 issue of National Geographic Traveller (UK)

Find us on social media

Facebook | Instagram | Twitter

Related Topics

- EDUCATIONAL TRAVEL

- CULTURAL TOURISM

- HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION

You May Also Like

An insider's guide to Denver, Colorado's wildly creative capital

They inspire us and teach us about the world: Meet our 2024 Travelers of the Year

For hungry minds.

10 reasons to visit the East Coast in 2024

An architectural tour of the Georgian capital, Tbilisi

7 of the UK's best gallery cafes

A long weekend in Orkney

How to plan a walking tour of Glasgow in the footsteps of Charles Rennie Mackintosh

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Coronavirus Coverage

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

MW19 | Boston

Boston, Massachusetts, USA, April 2-6, 2019

Approaching “Dark Heritage” Through Essential Questions: An Interactive Digital Storytelling Museum Experience

Akrivi Katifori , National Kapodistrian University of Athens & ATHENA Research Center, Greece, Klaoudia Marsella Restrepo Lopez , National Kapodistrian University of Athens., Greece, Dimitra Petousi , National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece, Manos Karvounis , University of Athens, Greece, Vassilis Kourtis , National and Kapodistrian University of Athens | ATHENA Research Center, Greece, Maria Roussou , National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece, Yannis Ioannidis , Univ. of Athens & ATHENA Research Center, Greece

Keywords: interactive digital storytelling, dark heritage, visitor study, essential questions

Introduction

The potential of digital storytelling in cultural heritage has been widely recognized as an effective technique for communicating heritage interpretation to the public and increasing the understanding of the past and its implications for the present (Staiff, 2014). Digital storytelling seems to offer the capability to reach a wider, more engaged and returning audience (Brittain and Clack 2007).

In previous research, initiatives like the EU funded projects CHESS ( http://www.chessexperience.eu/ ) (Katifori et al, 2014) and EMOTIVE ( https://www.emotiveproject.eu/ ) (Katifori et al, 2019), we have explored the potential of mobile digital storytelling and identified guidelines and best practices for the design and authoring of digital storytelling experiences at a heritage site (Roussou et al 2018, Perry et al 2017, Katifori et al., 2018).

In this paper, we apply this work for the design of a digital storytelling experience in the Criminology Museum of the University of Athens. The collections of the museum fall under the definition of “dark heritage,” as defined in the next section of the paper, featuring a variety of crime-scene evidence, including weapons and even human remains.

Part of the literature around dark tourism and heritage seems to emphasize a fascination with death as the main (and even sole) motive for visiting sites in which death is presented (Stone & Sharpley, 2008). The more morbid aspects of the Criminology Museum would at first glance seem to be ideal for a storytelling-based approach that would ensure visitors’ emotional engagement and fascination. However, a closer study of the museum history, current practice and objectives, as well as a comprehensive visitor study revealed that a difference approach would be better suited for this particular site.

In this work, we report on how we created a thought-provoking digital storytelling experience for the museum. Following a user-centered design methodology, we discerned that the motivation of the museum audience was not only to have an encounter with crime and death, but also to better understand and reflect upon the darker sides of human nature. Then, borrowing from education, we used the notion of “essential questions” as tools to stimulate thought, to provoke inquiry, and lead to a deeper understanding of how the world and human nature work (Jacobs, 1997) with the objective to develop an interactive digital storytelling experience for the museum.

In the following section, we refer to the the concept of “dark heritage” and then present the Criminology Museum as a dark-heritage site, followed by the findings of the visitor study we performed in the museum. Next, we focus on the concept of “essential questions” and their application in heritage, before going into the details on how we applied it in our digital storytelling experience. We conclude the work with our insight on guidelines for sites with similar characteristics as well as addressing open issues and challenges for the application of digital storytelling in dark heritage contexts.

Current Practice in Dark Heritage

Dark tourism (also referred to “black tourism” or “grief tourism”) has been defined as tourism involving travel to places historically associated with death and tragedy (Foley & Lennon, 1996)—some of them managed as entertainment venues and others with more focus on a historical- and heritage-related approach. The term “dark heritage” has been applied to both sites and artifacts, along with terms like “difficult heritage” and “dissonant heritage.” More specifically, dark cultural heritage can be defined as “cultural heritage that is associated with real and commodified sites of atrocity, death, disaster, human depravity, tragedy, human suffering, and sites of barbarism and genocide”(Kuznik, 2018).

Although dark heritage is relatively new as a term, the concept coincides with possibly one of the oldest types of tourism, as there is an innate human inquisitiveness and touristic attraction to places of death and horror (including popular public events of the past, such as public hangings, beheadings, the burning of witches, gladiatorial games, etc. (Kuznik, 2018).

There is a clear and identified tendency in the heritage sector to capitalize on the “product of dark tourism” and in a sense “milk the macabre,” (Dann, 1994) taking advantage of its willing consumption by the “dark tourist.” As suggested by Stone (2005), “within contemporary society, people regularly consume death and suffering in touristic form, seemingly in the guise of education and/or entertainment,” and sometimes tact and taste do not “prevail over economic considerations.” However, without the tourist demand, there would be no need to supply it.

A large part of dark tourism and heritage literature seems to emphasize this fascination with death as the main (and even sole) motive for visiting sites in which death is presented (Stone & Sharpley, 2008). This perspective is sometimes adopted in virtual storytelling experiences for dark heritage sites, and the ethical aspects of such approaches have been discussed in Fisher & Schoemann (2018). However, according to Biran et al., (2011) motives vary and include a desire to learn and understand the history presented and an interest in having an emotional heritage experience. (Rami and Erdinç, 2013).

In the end, the motivation behind exhibiting these sites is what partially dictates whether they are exploitative or not. In the next section, we attempt to clarify where the Criminology Museum stands in this respect.

The Athens University Criminology Museum as a Dark Heritage Site

The Athens University Criminology Museum ( http://www.criminology-museum.uoa.gr/ ) was founded in 1932, and since 1992, it has been housed within the Laboratory of Forensics and Toxicology of the Athens University Faculty of Medicine. Its collections are related to toxicology, criminology, forensic medicine, and weapons and present the history of crime in Greece in the 19th and 20th centuries. This is probably one of the most peculiar and special museums in Athens, more akin to the “curiosity rooms” of the 16th century, interestingly—not housed inside an amusement park but rather in the heart of an academic institution.

The museum is not open to the public daily and, until recently, operated only by appointment for special interest groups, such as students and specific organizations with an interest in arms or crime and forensics, gradually the wider public to visit. The museum opens one day per year to the public. The great number of visitors on this open day makes it evident that digital access to the museum collections should be made available to cater to this demand, to meet the needs of the audience while fulfilling the museum’s purpose of communicating heritage (Koutsis, 2019).

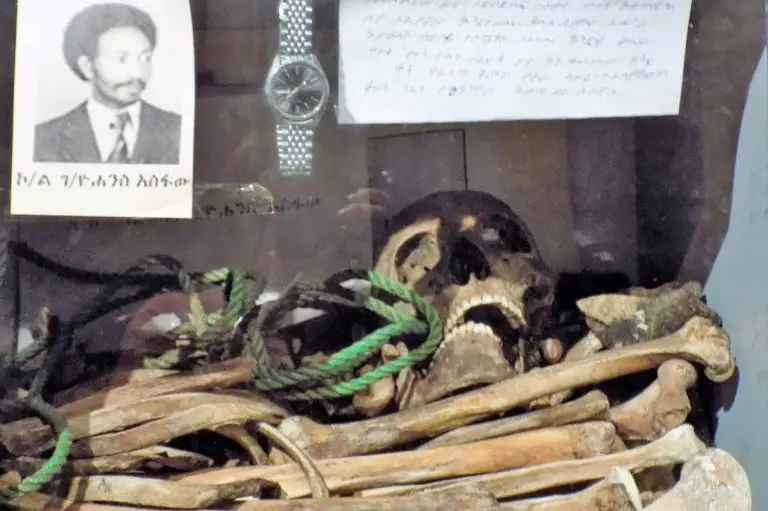

Visiting the museum can definitely be classified as a “dark heritage” experience. The collections cover different aspects of crime; however, death is a prominent and shocking theme. The human remains collection contains mummified heads of 19th-century bandits, remains preserved in glass jars and even a full-body mummy, whereas the wax models of the effects on the human body of different methods of murder, like gunshots to the head and actual crime-scene photos, add a strong emotional effect.

Figure 1: Wax body-part models, visualizing a physical attack

All of these strange exhibits are displayed without any intent to shock or capitalize on the macabre. They are naturally displayed as objects that have served their scientific or investigatory purpose and are now in waiting to be used again by young scientists and investigators in the context of their education—much like what one would expect of an evidence storage room in older times. This impression is consistent and confirmed by the history of the museum.

Figure 2: The ear and hand of A. Schinas, who murdered Georgios Α’, King of Greece

The founder and person responsible for the core of the collections was a professor of Forensic Medicine, Ioannis Georgiades (1874 – 1960). Georgiades was a gun enthusiast, avid collector of crime scene evidence and Olympic Fencing medallist in the 1886 Athens games as well as a dedicated researcher and philanthropist. It may seem strange that one person can combine such seemingly conflicting qualities. It is a given that studies of human nature, acting for good and evil, have been performed through Philosophy and Metaphysics. However, as science and technology are now able to provide a better understanding of these intriguing questions, experts in Forensics and Criminology are now called to give new answers about how accidents or crimes happen, identifying the reasons and sometimes the motives for the crime. This is why behind the exhibits, there is a hidden story—one that the first-time visitor can feel but not immediately realize, and that is the scientific research work of the Laboratory of Forensics and Toxicology.

Figure 3: General view of the museum gallery

The peculiar circumstances in which the evidence was produced and the specific context of the object acquisitions may easily explain the highly engaging quality of the permanent exhibition. However, this quality remains like a “dormant advantage” as there is a strong awareness among the Board members (who also serve as guides when tours are programmed) that shocking material is not to be blatantly exposed to the general public. The overall result is the emphasis on academic presentation, leaving the human stories behind the exhibits silent, mostly due to the limited time of the guided tours and to a shortage of personnel.

The above scientific approach, consistent with the founder’s vision, seems to be a conscious direction for the museum, ensuring a clear decision for fostering historical understanding and institutional education, without directly responding to the present fascination for the macabre.

Understanding the Museum Audience

As the Criminology Museum is accessible to the public only by appointment, the best way to study the type of audiences the museum would attract, if open, was to conduct a visitor study during the university museums’ Open Day event. This event takes place once a year. Only then, everybody is given the chance to visit all the Athens University museums, even those regularly closed to the public. They may choose to participate in guided tours or attend special events.

The visitor study was conducted on Saturday, October 7, 2017, 11:00am—3:00pm. During this time, the museum received 300 visitors who accessed the museum in groups of 30-45 and participated in a guided tour by one member of the museum staff. Of those, 137 were briefly interviewed at the end of their visit. In parallel, members of our team observed the visitors throughout the tour and tracked preferences in regard to visitor trajectories and time spent in the museum gallery after the end of the guided tour. For the needs of this work, we focus on the results of the study, which are relevant to the visit characteristics and the visitors’ preferences and needs.

Based on the evaluation team’s informal observations, most of the visitors lingered on even after the end of the guided tour to view the collections themselves, focusing on the ones that caught their attention most. In this sense, the mean-visit duration was closer to 45 minutes to 1 hour, significantly more than the expected 20—30 minutes of the guided tour. During the visit, the guided-tour participants seemed focused on the guide, and they were not discouraged, even by the ample use of scientific terminology by the experts. They listened to the interpretative information with interest, and then in their own time, they followed their personal paths of discovery of the exhibits.

This positive view of the museum is confirmed by the interviews as 86% confirmed that their expectations were met, and about 20% were very enthusiastic and commented on the “uniqueness” of the museum. 47% reported that they liked “all the collections.” 41% liked the guided tour, and 27% liked the forensic medicine collection, with special mentions to the embryos, the mummy, the human remains and the bandits’ mummified heads. There were also references to other exhibits like the guillotine, the firearms, the letters of the mentally ill, material related to the occult, the toxicology exhibits, etc.

A low 12% of the visitors reported that they were “partly satisfied” by the visit, whereas only three visitors said they were not satisfied at all. As to the reasons they were not satisfied by the visit, the majority (31%) reported the “small space.” 8.7% felt the time allocated to them for the visit was too little. 30% referred to issues related to the museological design and presentation of the collections, including the lack of more detailed information on specific exhibits and the fact the museum is not open to the public daily. Only a very small percentage referred to the shocking nature of some of the exhibits, like the embryos.

It is interesting that 66% of the visitors reported that they would recommend the museum to the wider public, without any restrictions. 38% felt that it is also appealed to special interest groups, as it could serve educational purposes as well as an inspiration for book writers. Some suggested that the museum could be accessible to high school students as “now psychology is taught in high schools by the age of 12” and “children now are familiar with harder images related to crime through television and the web.”

On the whole, the visitors expressed the wish that newer exhibits should be added to the collections and that the museum would benefit from a more modern approach in their presentation. Few reported the use of technological means as a necessity, whereas they felt that a communicative and friendly expert guide, like those met in the museum, always make the visit more pleasant. They saw the guide as a reliable source of anecdotal stories and of unique perspectives— somebody who is not a mere narrator of facts about the objects but an efficient communicator who enables discovery of the human aspects behind the real stories.

So, what makes the visitor experience so successful for almost all visitors in this museum, even though there was very limited and antiquated exhibition space and minimal interpretative material available? Was it the dark and shocking nature of the exhibits that made this difference? The visitor study revealed the opposite. Although some of the visitors were, in fact, drawn to the museum because it was “different,” its darker nature was not what made visitor engagement much longer than the allocated time. What seemed, in fact, to do the trick was the interaction with the criminal science experts and their “insider” scientific information, as well as the human stories they brought to life: stories of crime, yes, but more importantly, stories that revealed different aspects of human nature and provoked a deeper type of reflection.

An interesting find that reinforces the success of the guided tour as it is approached so far by the museum is that a very small percentage of the visitors, less than 1%, felt the need for the presence of “technological means,” for example, an audio guide. What they did appreciate was the “friendly staff,” the “scientific information,” and “impressing stories,” leading to a fuller “understanding of human nature.”

However, even though a digital app was not explicitly requested by the visitors, it was requested by the staff, who felt that they are not able to cover this strong demand for guided tours in the museum, due to their other research and investigatory duties in the Laboratory of Forensics and Toxicology.

It is a fact that a digital app cannot replace the expert, but can it be designed in such a way that it stays true to the guided tour’s more successful qualities? The next section presents “essential questions” as a design tool to this end.

“Essential Questions” as a Tool to Design for Heritage

The traditional assumption when designing museum exhibitions and informational content for cultural sites is that the visitor comes to the site with an appetite for information. Cultural institutions attempt to satisfy this appetite through traditional informational labels and audio guides or even more elaborate, multimedia approaches—all designed to offer to the visitor general information.