First Fleet

Transportation to the Australian colonies began in 1788 when the First Fleet, carrying between 750 and 780 convicts plus 550 crew, soldiers and family members, landed at Sydney Cove after an eight-month voyage. Over the next 80 years, British courts sentenced more than 160,000 convicts to transportation to Australia.

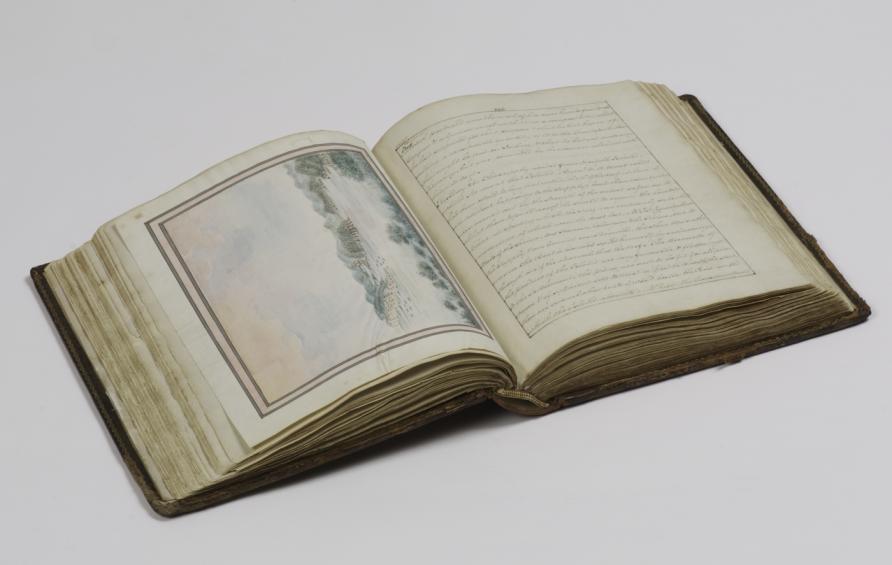

Arthur Bowes Smyth (1750-1790) was the ship’s surgeon aboard the Lady Penrhyn , one of the ships in the First Fleet. In his journal, Smyth wrote of the harsh conditions aboard the Lady Penrhyn whose passengers included 101 female convicts. The names of the convicts are listed on pages 17─20 of Smyth’s journal.

Smyth, Arthur Bowes, Journal of Arthur Bowes Smyth, 1787 March 22-1789 August, 1787, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-233345951

1. This is the fourth page from the journal that Arthur Bowes Smyth kept during his voyage to Australia on the Lady Penrhyn (one of the ships of the First Fleet). Share the page with your students and invite them to use ‘history detective’ skills to find the following information:

- What was the Lady Penrhyn ?

- Can you find the list of passengers? Name one of them.

- Can you find the list of marine officers and men? Name one of them.

- Can you find the list of boys? How many were there?

- Listed next to people’s names, can you find some of the jobs they did? List two of the jobs.

- The lists on this page do not include the names of most of the people on board the Lady Penrhyn . Who else might have been on board? Why might their names have been listed separately from those on this page?

Use the information the students have found to brainstorm ideas about why the First Fleet came to Australia. You may like to use the artwork Convicts Embarking for Botany Bay , painted by Thomas Rowlandson (1756─1827) in 1800, to stimulate the brainstorm.

Rowlandson, Thomas, 1756-1827. (1800). [Convicts embarking for Botany Bay] [picture] / T. Rowlandson . http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135232630

English artist Thomas Rowlandson depicts convicts being loaded onto a rowing boat at the beginning of a long voyage to the other side of the world. The two corpses hanging from a gibbet are a gruesome reminder of the alternative to transportation.

2. Read the following (edited) extracts from Bowes Smyth’s journal between March 1787 and January 1788 with your students.

Friday 22 March came on board the ship at the Mother-bank near Portsmouth (page 5) Friday 20th a fine day with a fresh breeze—a large and beautiful rainbow seen this day about 8 o’clock without any rain preceding its appearance, which the seamen say is a sign of the wind. Several large dolphins seen astern which would not take the baits (page 33) Wednesday 19 a very wet day and frequent very violent squalls of wind, about 11 o’clock a.m. some person fell overboard from the Charlotte … have not learnt who fell overboard or if they were saved (page 58) Saturday 1st December This day one of the convicts on board our ship ( Margarett Brown ) scalded her foot very bad. Tis very extraordinary how very healthy the convicts on board this ship in particular, and indeed in the fleet in general have been (page 78) Tuesday 25 December 1787 Xmas Day We are now about two thousand miles distant from the South Cape of New Holland, or Van Diemen’s Land, or otherwise Adventure Bay, with a most noble breeze which carries us at 8½ knots per hour, which we hope will enable us to see land in about a fortnight (page 97) 26 January … about 7 o’clock p.m. we reach the mouth of Broken Bay, Port Jackson, and sailed up into the cove where the settlement is to be made … the finest terraces lawns and grottos with distinct plantations of the tallest and most stately trees I ever saw in any noble man’s gardens in England cannot exceed in beauty those which nature now presented to our view (page 131)

As a class, discuss what these extracts tell us. Ask your students the following questions:

- What were some of the challenges faced by the people on the First Fleet during their voyage to Australia?

- Why do you think the people on the ships were trying to bait the dolphins?

- What pleasant experiences does Bowes Smyth write about in these extracts from his journal?

- What was Bowes Smyth’s first impression of Sydney Cove?

3. The experiences of the convicts on the Lady Penrhyn would have been very different to Bowes Smyth’s experience as ship’s surgeon. Ask your students to imagine they are convicts on board the ship. Each student should write four journal entries that show what the convicts may have experienced during the voyage from Portsmouth to Sydney.

Other Treasures sources that relate to the concepts explored in this source include: Early settlement , Strange creatures

The National Library of Australia acknowledges Australia’s First Nations Peoples – the First Australians – as the Traditional Owners and Custodians of this land and gives respect to the Elders – past and present – and through them to all Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Cultural Notification

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this website contains a range of material which may be considered culturally sensitive including the records of people who have passed away.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware this website contains images, voices and names of people who have died.

Exile or opportunity?

1788: Captain Arthur Phillip establishes a convict settlement at Sydney Cove

Colonial Australia

Indigenous Australia

Learning area

Use the following additional activities and discussion questions to encourage students (in small groups or as a whole class) to think more deeply about this defining moment.

Questions for discussion

1. What, if any, have been the long-term effects of convict transportation on Australian society?

2. Do you agree with the National Museum of Australia that the arrival of the First Fleet is a defining moment in Australian history? Explain your answer.

Image activities

1. Look carefully at all the images for this defining moment. Tell this story in pictures by placing them in whatever order you think works best. Write a short caption under each image.

2. Which 3 images do you think are the most important for telling this story? Why?

3. If you could pick only one image to represent this story, which one would you choose? Why?

Finding out more

1. What else would you like to know about this defining moment? Write a list of questions and then share these with your classmates. As a group, create a final list of 3 questions and conduct some research to find the answers.

In a snapshot

The arrival of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove in January of 1788 marked the beginning of the European colonisation of Australia. The fleet was made up of 11 ships carrying convicts from Britain to Australia. Their arrival changed forever the lives of the Eora people, the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land in the Sydney area, and began waves of convict transportation that lasted until 1868.

‘Sketch & description of the settlement at Sydney Cove Port Jackson in the County of Cumberland.’ Drawn by Francis Fowkes.

National Library of Australia, MAP NK 276

Can you find out?

1. Who were Australia’s first convicts? Why were they transported to Australia?

2. How did Governor Arthur Phillip manage the colony of New South Wales?

3. What were the main ways Aboriginal people were affected by the arrival of Phillip and the First Fleet?

Colour publication printed for the 150th Anniversary Celebrations of Australia, 1938. Captain Arthur Phillip is featured.

National Museum of Australia

Why was a convict colony set up in Australia?

Britain used transportation to distant lands as a way of getting rid of prisoners. After Britain lost its American colonies in 1783 the jails of England were full. The British decided to begin transporting prisoners to Australia, which had recently been claimed for the British Crown by Lieutenant James Cook.

Prisoners (also known as convicts) were transported for many reasons but mainly for crimes that we might consider to be minor today, such as stealing. Convicts who were transported were usually poor, often from the large industrial cities and were mostly from England (with a large minority from Ireland and Scotland).

The First Fleet of 11 ships, commanded by Captain Arthur Phillip, set up a convict settlement at Sydney Cove (now Circular Quay) on 26 January 1788. This was the beginning of convict settlement in Australia.

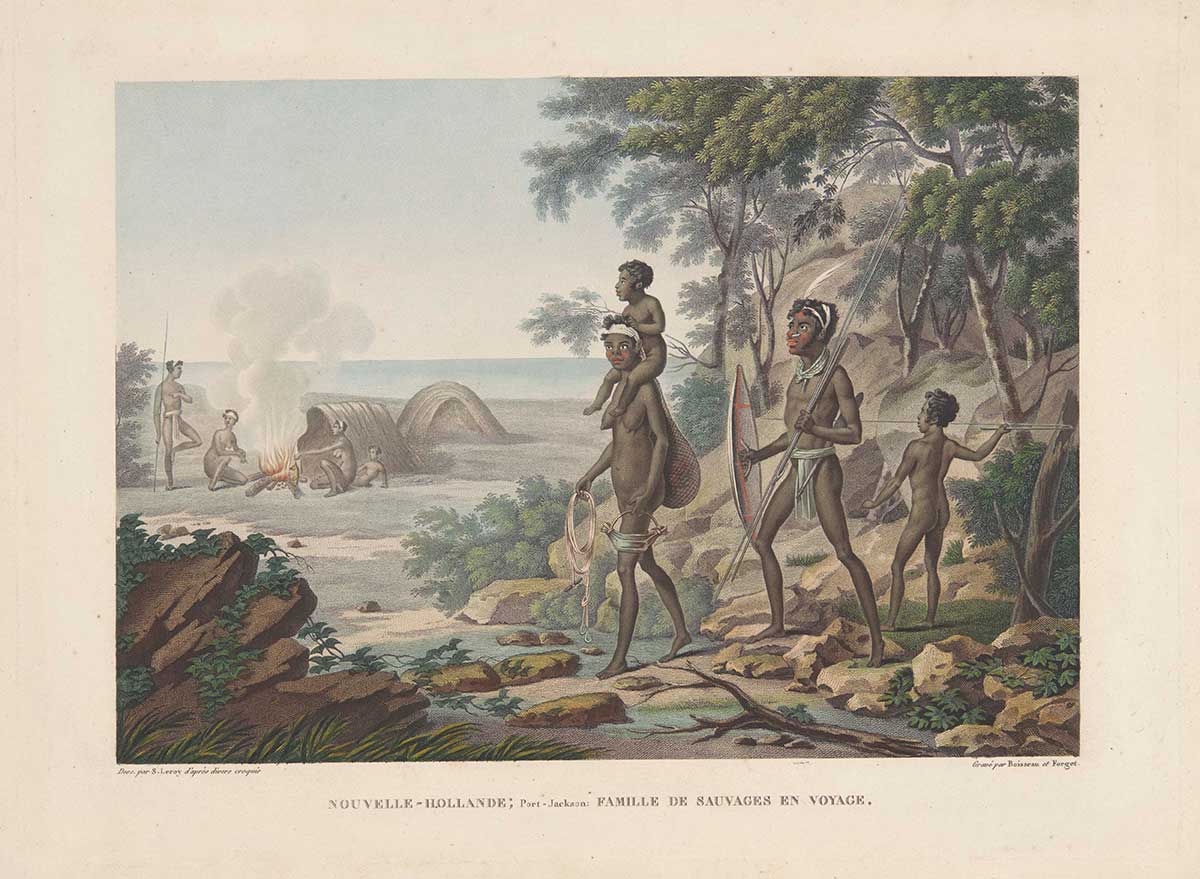

A colour engraving of a family of four travelling in the Port Jackson area

Who was Australia’s first governor?

Captain Arthur Phillip was an experienced naval officer who became first governor of the colony of New South Wales. He faced many challenges in the early years of settlement. He was prepared to punish people who broke the rules, but also rewarded convicts and free settlers who behaved well.

Almost straight away, the new colony faced starvation. The first crops failed because of the lack of skilled farmers, spoilt seed brought from England, poor local soils, an unfamiliar climate and bad tools. Phillip insisted that food be shared between convicts and free settlers. The British Officers didn’t like this, nor the fact that Phillip gave land to trustworthy convicts. But both actions meant that the colony survived, and they began an attitude of fairness that is still prized in Australia today.

Research task

Research the sorts of people who travelled on the 11 ships that made up the First Fleet. How many convicts (male and female), free settlers, crew, marines, officials and children were on board?

‘A Family of New South Wales’, based on a sketch by Captain Philip Gidley King, 1793

What effect did the First Fleet have on Australia’s first peoples?

The arrival of the First Fleet immediately affected the Eora nation, the traditional Aboriginal owners of the Sydney area. Violence between settlers and the Eora people started as soon as the colony was set up. The Eora people, particularly the warrior Pemulwuy, fought the colonisers. This conflict was mainly over land and food.

Phillip was speared during a meeting with Eora at Manly in 1790, but he recovered and continued as the colony’s first governor for two more years. He returned to England in 1792 with two Indigenous men: Bennelong, who later returned to Australia, and Yemmerrawannie, who died in England.

Thousands of Eora people died as a result of European diseases like smallpox.

The founding of Australia by Capt. Arthur Phillip R.N. Sydney Cove, Jan. 26th 1788 , by Algernon Talmage, 1937

This map attempts to represent the language, social or nation groups of Aboriginal Australia. It shows only the general locations of larger groupings of people which may include clans, dialects or individual languages in a group. It used published resources from 1988-1994 and is not intended to be exact, nor the boundaries fixed. It is not suitable for native title or other land claims.

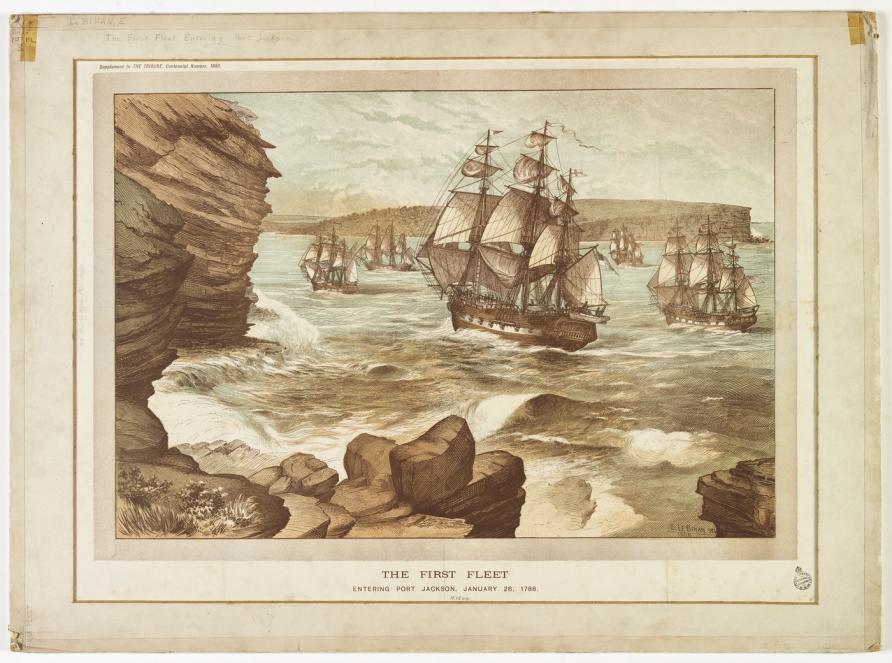

The First Fleet entering Port Jackson, January 26, 1788 , by E Le Bihan, drawn in 1888

Captain Arthur Phillip, painted by Francis Wheatley

Port Jackson Harbour , by John Eyre and engraved by Walter Preston, 1812

Convict leg irons

An engraving believed to be the only known depiction of Pemulwuy

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, FL3141725

David R Horton (creator), AIATSIS, 1996. No reproduction without permission. To purchase a print version visit: www.aiatsis.ashop.com.au/

State Library of New South Wales FL3268277

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales a928087

Convict love token, 1792

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

State Library of New South Wales Q80/18

What were the long-term effects of the First Fleet?

The First Fleet was the beginning of convict transportation to Australia and was followed by many other fleets of convict ships. When this ended in 1868, over 150,000 convicts had been transported to New South Wales and other Australian colonies. Most convicts stayed in Australia after serving their sentences, and some became well-known, important people within the Australian colonies.

Convict settlement continued to have devastating effects on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the decades after 1788. Thousands died in conflicts with settlers and from diseases, and many more suffered from the loss of cultural traditions and languages.

Read a longer version of this Defining Moment on the National Museum of Australia’s website .

What did you learn?

Related resources, australian journey episode 06: captivity narratives, 1.2 convicts sent to australia: ‘when prisoners walked the land’, convict punishment, collection highlights: convict love tokens.

Convict transportation peaks

Convict transportation ends

HISTORIC ARTICLE

May 13, 1787 ce: 'first fleet' sets sail for australia.

On May 13, 1787, the “First Fleet” of military leaders, sailors, and convicts set sail from Portsmouth, England, to found the first European colony in Australia, Botany Bay.

Geography, Social Studies, World History

Loading ...

On May 13, 1787, a group of over 1,400 people in 11 ships set sail from Portsmouth, England. Their destination was a vaguely described bay in the continent of Australia, newly discovered to Europeans. In a stunning feat of planning and navigation , nearly all of the voyagers survived and arrived in Botany Bay several months later.

A wide variety of people made up this legendary “First Fleet .” Military and government officials, along with their wives and children, led the group. Sailors, cooks, masons, and other workers hoped to establish new lives in the new colony .

Perhaps most famously, the First Fleet included more than 700 convicts . The settlement at Botany Bay was intended to be a penal colony . The convicts of the First Fleet included both men and women. Most were British, but a few were American, French, and even African. Their crimes ranged from theft to assault. Most convicts were sentenced to seven years’ “transportation” (the term for the sending of prisoners to a usually far-off penal colony ).

The First Fleet departed from Portsmouth, then briefly docked in the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa. The ships then crossed the Atlantic Ocean to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where they took on huge stores of supplies. Then the fleet sailed back across the Atlantic to Cape Town, South Africa, where they took on even more food, including livestock . The main portion of the journey was across the entire Indian Ocean, from Cape Town to Botany Bay —they traveled about 24,000 kilometers (15,000 miles) throughout the entire journey.

Botany Bay was not as hospitable as the group had hoped. The bay was shallow, there was not a large supply of freshwater, and the land was not fertile . Nearby, however, officers of the First Fleet discovered a beautiful harbor with all those qualities. They named it after the British Home Secretary, Lord Sydney. The day the First Fleet discovered Sydney Harbor is celebrated as Australia’s national holiday , Australia Day.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

First Fleet Fellowship Victoria Inc

Descendants of those who arrived with the First Fleet in 1788 with Captain Arthur Phillip

October 15, 2011 by Cheryl Timbury

How one London newspaper recorded history

Government is now about settling a colony in New Holland, in the Indian seas; and the Commissioners of the Navy are now advertising for 1500 ton of transports. This settlement is to be formed at Botany Bay, on the west side of the island, where Captain Cook refreshed and staid for some time on his voyage in 1770.

As he first sailed around that side of the island. he called it New South Wales, and the two Capes at the mouth of the river were called by the names of Banks and Solander.

There are 680 men felons and 70 women felons to go, and they are to be guarded by 12 marines and a corporal in every transport, containing 150 felons. There are several men of war and some frigates to go, but they all come back, but one or two of each, which are to remain there for some time to assist in establishing a garrison of 300 men intended to be left there.

The whole equipment, army, navy and felons, are to be landed with two years’ provisions, and all forms of implements for the culture of the earth, and hunting and fishing, and some light buildings are to be run up immediately till a proper fort and town-house are erected. This place is nearly in the same latitude with the Cape of Good Hope, and about eight months’ voyage from land.

– The Daily Universal Register September 14, 1786

Chronology of the First Fleet 1776 The American War of Independence begins. The former American colonies refuse to accept British convicts 1781-2 Two attempts to establish a convict colony in West Africa end in disaster with most of the convicts dying from disease or privation or escaping. 1783 August Peace with America prompts the despatch of the Swift transport. The convicts mutiny in the Channel and many escape at Rye, Sussex. The remainder are sent on to Maryland. 1784 March Mercury sails for America with 179 convicts. A mutiny again takes place, and many escape at Torbay, Devon. Those remaining on board are sent on to America and eventually landed on the Mosquito coast in Central America after being rejected by the newly Independent United States. 1776 August 18 Lord Sydney writes to the Treasury requesting the provision of ships to carry convicts to New South Wales.

Australia First Day Cover 6 August 1986 – New South Wales the decision to settle – stamps feature King George 111, Lord Sydney, Captain Arthur Phillip, Captain John Hunter (C Timbury collection)

1787 January 6 The first group of convicts are embarked on Alexander at Woolwich, London. 1787 May 13 The First Fleet sails from Portsmouth, Hampshire. 1787 June 3 Arrival at Madeira. Water and fresh supplies taken on board. 1787 July 14 Fleet crosses equator. 1787 August 6 Arrival at Rio de Janiero. Fleet undergoes repairs, takes on fresh water and supplies. 1787 September 4 Fleet departs Rio. 1787 October 14 Arrival at Cape of Good Hope. Fresh supplies and livestock taken on board. 1787 November 12 Departs from the Cape (Table Bay). 1787 November 25 Captain Phillip divides the Fleet and sails ahead with the four fastest ships. 1787 December 25 Christmas Day Aboard Prince of Wales Being Christmas day, Latd 42 degrees 16. Longd. 105 degrees 00 East, Wind Fair, Weather Heasey, Dinned off a pice of pork and apple Sauce a pice of Beef and plum pudding, and Crowned the Day with four bottles of Rum, Which was the Best. Wee Vitr’ens Could Afford James Scott Seargeant of Marines 1788 January 3 Coast of Van Diemans Land (Tasmania) sighted. 1788 January 18/19 The first division of the Fleet anchors at Botany Bay.

The First Fleet Entering Botany Bay

1788 January 20 The remainder of the Fleet arrives.

1788 January 26 All Fleet ships anchor in Sydney Cove, Port Jackson. Captain Phillip and officers go ashore, raise the flag, and toast the new colony. Two French ships commanded by La Perouse enter Botany Bay.

Route of First Fleet taken off ‘School Project – The First Fleet and Early Sydney 1788-1810’ School Projects can be purchased through Saleable items

1788 February 15 Supply sails for Norfolk Island carrying a small party to establish a settlement. 1788 March 10 The La Perouse expedition leaves Botany Bay. 1788 May 5/ 6 Charlotte, Lady Penrhyn and Scarborough sail for China. 1788 July 14 Borrowdale, Alexander, Friendship and Prince of Wales sail for England. 1788 October 2 Golden Grove sails for Norfolk Island with a party of convicts, returning to Port Jackson. 1788 November 10 Sirius sails for Cape of Good Hope for supplies. 1788 November 19 Fishburn and Golden Grove sail for England. Only Supply now remains. 1789 December 23 HMS Guardian carrying stores for the colony strikes an iceberg and is forced back to the Cape. It never reaches New South Wales. 1790 March 19 Sirius wrecked off Norfolk Island. 1790 April 17 Supply sent to Batavia, Java, for emergency food supplies. 1790 June 3 Lady Juliana, which left England in July 1789, arrives only three weeks before the Second Fleet ships, saving the colony from starvation and bringing orders for the recall of the marines to be replaced by soldiers of the NSW corps. 1791 March 28 Waaksamheld sails for England carrying the crew of Sirius. 1791 August/October The Third Fleet arrives. 1791 December 18 HMS Gorgon sails for England carrying many First Fleet marines home to England. 1792 December 11 Atlantic sails for England carrying Governor Phillip and the remaining First Fleet marines who had chosen not to stay in the colony.

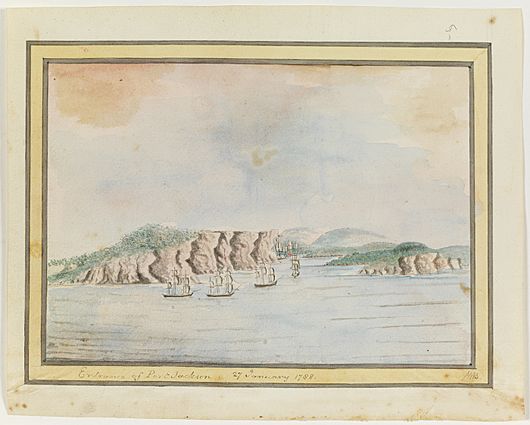

Captain Phillip’s first sight of Port Jackson in Spy Sloop

Source: Gillen, Mollie The Founder of Australia – A Biographical Dictionary of the First Fleet , Libary of Australian History, Sydney 1989

Australian Settlers Monuments In Old Portsmouth on the walkway by the sea wall at the junction of Broad Street and High Street near Square Tower..

First Fleet memorial Portsmouth (Bruce Hunter)

First Fleet Memorial Portsmouth (Bruce Hunter) Its twin is located in Sydney

Memorial Bonds of Friendship was unveiled by The Queen on 11 July 1980. The block of granite was quarried in NSW and given by the Citizens of Australia.

A twin monument was unveiled at Circular Quay, Sydney Australia, in 1980 as part of the Bicentenary Celebrations. The memorial was later moved to Loftus Street Sydney

Bicentenary Links, Loftus Street Sydney NSW (C Timbury)

© First Fleet Fellowship Victoria Inc 2011

Recent Posts

- RETIREMENT OF GOVERNOR PHILLIP

- SIR JOSEPH BANKS on BOTANY BAY

- Mary Bishop (née Davies/Davis)

- Governor Phillip’s Foundation Plate, 15th May 1788

- THE WONDERFUL KANGAROO

Connect with First Fleet Fellowship Victoria Inc on Facebook

Finding your way around this site

Please use our search function to find specific information, if not click on one of the categories below to find the articles you want.

This website has been archived and is no longer updated.

Nsw migration heritage centre, documenting australia's migration history.

THE FIRST FLEET, BOTANY BAY AND THE BRITISH PENAL COLONY

The First Fleet of 11 ships, each one no larger than a Manly ferry, left Portsmouth in 1787 with more than 1480 men, women and children onboard. Although most were British, there were also African, American and French convicts. After a voyage of three months the First Fleet arrived at Botany Bay on 24 January 1788. Here the Aboriginal people, who had lived in isolation for 40,000 years, met the British in an uneasy stand off at what is now known as Frenchmans Beach at La Perouse.

On 26 January two French frigates of the Lapérouse expedition sailed into Botany Bay as the British were relocating to Sydney Cove in Port Jackson. The isolation of the Aboriginal people in Australia had finished. European Australia was established in a simple ceremony at Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788.

- Bookmark on Delicious

- Recommend on Facebook

- Share with Stumblers

- Tweet about it

- Convicts: Bound for Australia

- State Library of NSW

- Research Guides

- Family History

First Fleet convicts

- About the guide

- Getting started

- Trial & court records

- Prisons & hulks

- Voyage out to Australia

- Second Fleet convicts

- Convict arrivals, 1788-1842

- Index to probationary convicts to Sydney and Moreton Bay, 1849-1850

- Assize Courts, 1775-1853

- Criminal entry books, 1786-1871 (HO 13)

- Criminal entry books, 1850-1871 (HO 25)

- Criminal registers, England & Wales, 1805-1868 (HO 27 Series 2)

- Criminal registers for Middlesex, 1791–1849 (HO 26 Series 1)

- Quarter Sessions Court records, 1723-1878

- List of Quarter Sessions Court records held at the Library

- Session records of the Old Bailey, 1815-1849 (HO 16)

- The National Archives (UK) - Petitions for mercy, 1784-1830

- Prison commission prison books, 1816-1866 (PCOM 2)

- Prison records held in the miscellaneous series of the AJCP for England and Wales, 1723-1878

- List of Quarter Sessions Court and UK prison records held at the Library

- Quarterly returns of convicts in gaols and hulks, 1824-1876 (HO 8)

- Transportation lists, 1829-1840

- Treasury Board hulk returns, 1783–1803 (T1)

- UK Prison hulk registers & letter books, 1802-1849 (HO 9)

- Chronological list of hulks

- Hulk records explained

- Log of logs

- Musters and other papers relating to convict ships, 1790-1849

- Ships card index

- Surgeons' journals, 1816-1856

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander visitors are kindly advised that this website includes images, sounds and names of people who have passed.

All users should be aware that some topics or historical content may be culturally sensitive, offensive or distressing, and that some images may contain nudity or are of people not yet identified. Certain words, terms or descriptions may reflect the author's/creator's attitude or that of the period in which they were written, but are now considered inappropriate in today's context.

Key to library resources

The First Fleet, consisting of 11 vessels, was the largest single contingent of ships to sail into the Pacific Ocean. Its purpose was to find a convict settlement on the east coast of Australia, at Botany Bay.

The First Fleet sailed from England on 13 May 1787 and arrived at Botany Bay eight months later, on 18 January 1788. Governor Arthur Phillip rejected Botany Bay choosing instead Port Jackson, to the north, as the site for the new colony; they arrived there on 26 January 1788.

The number of convicts transported in the First Fleet is unclear; there were between 750-780 convicts and around 550 crew, soldiers and family members.

Reference Flannery, T 1999, The birth of Sydney , Text Publishing, Melbourne.

Ships of the First Fleet

- Golden Grove

- Lady Penrhyn

- Prince of Wales

- Scarborough

- << Previous: Voyage out to Australia

- Next: Second Fleet convicts >>

- Español NEW

First Fleet facts for kids

The First Fleet was a fleet of 11 British ships that brought the first British colonists and convicts to Australia. It was made up of two Royal Navy vessels, three store ships and six convict transports. On 13 May 1787 the fleet under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip , with over 1400 people ( convicts , marines, sailors , civil officers and free settlers), left from Portsmouth , England and took a journey of over 24,000 kilometres (15,000 mi) and over 250 days to eventually arrive in Botany Bay , New South Wales , where a penal colony would become the first British settlement in Australia.

Convict transports

Golden grove, preparing the fleet, leaving portsmouth, arrival in australia, first contact, after january 1788, last survivors, commemoration garden, first fleet park.

Lord Sandwich , together with the President of the Royal Society , Sir Joseph Banks , the eminent scientist who had accompanied Lieutenant James Cook on his 1770 voyage , was advocating establishment of a British colony in Botany Bay , New South Wales . Banks accepted an offer of assistance from the American Loyalist James Matra in July 1783. Under Banks's guidance, he rapidly produced "A Proposal for Establishing a Settlement in New South Wales" (24 August 1783), with a fully developed set of reasons for a colony composed of American Loyalists, Chinese and South Sea Islanders (but not convicts). The decision to establish a colony in Australia was made by Thomas Townshend, Lord Sydney , Secretary of State for the Home Office. This was taken for two reasons: the ending of transportation of criminals to North America following the American Revolution , as well as the need for a base in the Pacific to counter French expansion .

In September 1786, Captain Arthur Phillip was appointed Commodore of the fleet, which came to be known as the First Fleet, which was to transport the convicts and soldiers to establish a colony at Botany Bay. Upon arrival there, Phillip was to assume the powers of Captain General and Governor in Chief of the new colony . A subsidiary colony was to be founded on Norfolk Island , as recommended by Sir John Call and Sir George Young, to take advantage for naval purposes of that island's native flax ( harakeke ) and timber.

The cost to Britain of outfitting and dispatching the Fleet was £84,000 (about £9.6 million, or $19.6 million as of 2015).

Royal Naval escort

On 25 October 1786 the 10-gun HMS Sirius , lying in the dock at Deptford, was commissioned, and the command given to Phillip. The armed tender HMS Supply under command of Lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball was also commissioned to join the expedition. On 15 December, Captain John Hunter was assigned as second captain to Sirius to command in the absence of Phillip, whose presence, it was to be supposed, would be requisite at all times wherever the seat of government in that country might be fixed.

Sirius was Phillip’s flagship for the fleet. She had been converted from the merchantman Berwick , built in 1780 for Baltic trade. She was a 520 ton, sixth-rate vessel, originally armed with ten guns, four six-pounders and six carronades, Phillip had ten more guns placed aboard.

Supply was designed in 1759 by shipwright Thomas Slade, as a yard craft for the ferrying of naval supplies. Measuring 170 tons, she had two masts, and was fitted with four small 3-pounder cannons and six 1 ⁄ 2 -pounder swivel guns. Her armament was substantially increased in 1786 with the addition of four 12-pounder carronades.

Food and supply transports

Ropes, crockery , agricultural equipment and a miscellany of other stores were needed. Items transported included tools, agricultural implements, seeds, spirits, medical supplies, bandages, surgical instruments, handcuffs, leg irons and a prefabricated wooden frame for the colony's first Government House. The party had to rely on its own provisions to survive until it could make use of local materials, assuming suitable supplies existed, and grow its own food and raise livestock.

The reverend Richard Johnson, chaplain for the colony, travelled on the Golden Grove with his wife and servants.

Scale models of all the ships are on display at the Museum of Sydney . The models were built by ship makers Lynne and Laurie Hadley, after researching the original plans, drawings and British archives. The replicas of Supply , Charlotte , Scarborough , Friendship , Prince of Wales , Lady Penrhyn , Borrowdale , Alexander , Sirius , Fishburn and Golden Grove are made from Western Red or Syrian Cedar.

Nine Sydney harbour ferries built in the mid-1980s are named after First Fleet vessels. The unused names are Lady Penrhyn and Prince of Wales .

The majority of the people travelling with the fleet were convicts, all having been tried and convicted in Great Britain , almost all of them in England. Many are known to have come to England from other parts of Great Britain and, especially, from Ireland; at least 14 are known to have come from the British colonies in North America; 12 are identified as black (born in Britain, Africa, the West Indies, North America, India or a European country or its colony). The convicts had committed a variety of crimes, including theft, perjury, fraud, assault, robbery, for which they had variously been sentenced to death, which was then commuted to penal transportation for 7 years, 14 years, or the term of their natural life.

Four companies of marines volunteered for service in the colony, these marines made up the New South Wales Marine Corps, under the command of Major Robert Ross , a detachment on board every convict transport. The families of marines also made the voyage.

A number of people on the First Fleet kept diaries and journals of their experiences, including the surgeons, sailors, officers, soldiers, and ordinary seamen. There are at least eleven known manuscript Journals of the First Fleet in existence as well as some letters.

The exact number of people directly associated with the First Fleet will likely never be established, as accounts of the event vary slightly. A total of 1,420 people have been identified as embarking on the First Fleet in 1787, and 1,373 are believed to have landed at Sydney Cove in January 1788. In her biographical dictionary of the First Fleet, Mollie Gillen gives the following statistics:

While the names of all crew members of Sirius and Supply are known, the six transports and three store ships may have carried as many as 110 more seamen than have been identified – no complete musters have survived for these ships. The total number of persons embarking on the First Fleet would, therefore, be approximately 1,530 with about 1,483 reaching Sydney Cove.

According to the first census of 1788 as reported by Governor Phillip to Lord Sydney, the non-indigenous population of the colony was 1,030 and the colony also consisted of 7 horses, 29 sheep, 74 swine, 6 rabbits, and 7 cattle.

The following statistics were provided by Governor Phillip:

The chief surgeon for the First Fleet, John White, reported a total of 48 deaths and 28 births during the voyage. The deaths during the voyage included one marine, one marine's wife, one marine's child, 36 male convicts, four female convicts, and five children of convicts.

Notable members of First Fleet

- Captain Arthur Phillip , R.N, Governor of New South Wales

- Major Robert Ross , Lieutenant Governor and commander of the marines

- Captain David Collins , Judge Advocate

- Augustus Alt, Surveyor

- John White , Principal Surgeon

- William Balmain, assistant Surgeon

- Richard Johnson, chaplain

- Lieutenant George Johnston

- Captain Watkin Tench

- Lieutenant William Dawes

- Lieutenant Ralph Clark

- Captain John Hunter, commander of HMS Sirius

- Lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball, commander of HMS Supply

- Lieutenant William Bradley, 1st lieutenant of HMS Sirius

- Lieutenant Philip Gidley King , commandant of Norfolk Island

- Arthur Bowes Smyth , ship’s surgeon on Lady Penrhyn

- Lieutenant John Shortland, Agent for Transports

- John Shortland , son of above, 2nd mate of HMS Sirius

- Thomas Barrett, first person executed in colony

- Mary Bryant, with her husband, children and 6 other convicts escaped the colony and eventually returned to England

- John Caesar , bushranger

- Matthew Everingham, a 'profligate person', attorney's clerk. First person to come ashore, first man married in NSW and Father of the first child born in NSW, later explored Blue Mountains.

- Henry Kable, businessman

- James Martin, was part of the escape with Mary Bryant, wrote autobiography

- James Ruse , farmer, one of the only ones in the colony at its establishment

- Robert Sidaway, baker, opened the first theatre in Sydney

- James Squire, brewer

- Frances Williams , first Welsh woman to settle in Australia

In September 1786 Captain Arthur Phillip was chosen to lead the expedition to establish a colony in New South Wales . On 15 December, Captain John Hunter, was appointed Phillip’s second. By now HMS Sirius had been nominated as flagship, with Hunter holding command. The armed tender HMS Supply under command of Lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball had also joined the fleet.

With Phillip in London awaiting Royal Assent for the bill of management of the colony, the loading and provisioning of the transports was carried out by Lieutenant John Shortland, the agent for transports.

On 16 March 1787, the fleet began to assemble at its appointed rendezvous, the Mother Bank , Isle of Wight . His Majesty's frigate Sirius and armed tender Supply , three store-ships, Golden Grove , Fishburn and Borrowdale , for carrying provisions and stores for two years; and lastly, six transports; Scarborough and Lady Penrhyn , from Portsmouth ; Friendship and Charlotte , from Plymouth ; Prince of Wales , and Alexander , from Woolwich . On 9 May Captain Phillip arrived in Portsmouth, the next day coming aboard the ships and give orders to prepare the fleet for departure.

Phillip first tried to get the fleet to sail on 10 May, but a dispute by sailors of the Fishburn about pay, they refused to leave until resolved. The fleet finally left Portsmouth, England on 13 May 1787. The journey began with fine weather, and thus the convicts were allowed on deck. The Fleet was accompanied by the armed frigate HMS Hyaena until it left English waters. On 20 May 1787, one convict on Scarborough reported a planned mutiny; those allegedly involved were flogged and two were transferred to Prince of Wales . In general, however, most accounts of the voyage agree that the convicts were well behaved. On 3 June 1787, the fleet anchored at Santa Cruz at Tenerife . Here, fresh water, vegetables and meat were brought on board. Phillip and the chief officers were entertained by the local governor, while one convict tried unsuccessfully to escape. On 10 June they set sail to cross the Atlantic to Rio de Janeiro , taking advantage of favourable trade winds and ocean currents.

The weather became increasingly hot and humid as the Fleet sailed through the tropics. Vermin, such as rats, and parasites such as bedbugs, lice , cockroaches and fleas, tormented the convicts, officers and marines. Bilges became foul and the smell, especially below the closed hatches, was over-powering. While Phillip gave orders that the bilge-water was to be pumped out daily and the bilges cleaned, these orders were not followed on Alexander and a number of convicts fell sick and died. Tropical rainstorms meant that the convicts could not exercise on deck as they had no change of clothes and no method of drying wet clothing. Consequently, they were kept below in the foul, cramped holds. In the doldrums , Phillip was forced to ration the water to three pints a day.

The Fleet reached Rio de Janeiro on 5 August and stayed for a month. The ships were cleaned and water taken on board, repairs were made, and Phillip ordered large quantities of food. The women convicts' clothing had become infested with lice and was burnt. As additional clothing for the female convicts had not arrived before the Fleet left England, the women were issued with new clothes made from rice sacks. While the convicts remained below deck, the officers explored the city and were entertained by its inhabitants. A convict and a marine were punished for passing forged quarter-dollars made from old buckles and pewter spoons.

The Fleet left Rio de Janeiro on 4 September to run before the westerlies to the Table Bay in southern Africa, which it reached on 13 October. This was the last port of call, so the main task was to stock up on plants, seeds and livestock for their arrival in Australia. The livestock taken on board from Cape Town destined for the new colony included two bulls, seven cows, one stallion, three mares, 44 sheep, 32 pigs, four goats and "a very large quantity of poultry of every kind". Women convicts on Friendship were moved to other transports to make room for livestock purchased there. The convicts were provided with fresh beef and mutton, bread and vegetables, to build up their strength for the journey and maintain their health. The Dutch colony of Cape Town was the last outpost of European settlement which the fleet members would see for years, perhaps for the rest of their lives. "Before them stretched the awesome, lonely void of the Indian and Southern Oceans, and beyond that lay nothing they could imagine."

Assisted by the gales in the " Roaring Forties " latitudes below the 40th parallel, the heavily laden transports surged through the violent seas. In the last two months of the voyage, the Fleet faced challenging conditions, spending some days becalmed and on others covering significant distances; Friendship travelled 166 miles one day, while a seaman was blown from Prince of Wales at night and drowned. Water was rationed as supplies ran low, and the supply of other goods including wine ran out altogether on some vessels. Van Diemen's Land was sighted from Friendship on 4 January 1788. A freak storm struck as they began to head north around the island, damaging the sails and masts of some of the ships.

On 25 November, Phillip had transferred to Supply . With Alexander , Friendship and Scarborough , the fastest ships in the Fleet, which were carrying most of the male convicts, Supply hastened ahead to prepare for the arrival of the rest. Phillip intended to select a suitable location, find good water, clear the ground, and perhaps even have some huts and other structures built before the others arrived. This was a planned move, discussed by the Home Office and the Admiralty prior to the Fleet's departure. However, this "flying squadron" reached Botany Bay only hours before the rest of the Fleet, so no preparatory work was possible. Supply reached Botany Bay on 18 January 1788; the three fastest transports in the advance group arrived on 19 January; slower ships, including Sirius , arrived on 20 January.

This was one of the world's greatest sea voyages – eleven vessels carrying about 1,487 people and stores had travelled for 252 days for more than 15,000 miles (24,000 km) without losing a ship. Forty-eight people died on the journey, a death rate of just over three percent.

It was soon realised that Botany Bay did not live up to the glowing account that the explorer Captain James Cook had provided. The bay was open and unprotected, the water was too shallow to allow the ships to anchor close to the shore, fresh water was scarce, and the soil was poor. First contact was made with the local indigenous people, the Eora , who seemed curious but suspicious of the newcomers. The area was studded with enormously strong trees. When the convicts tried to cut them down, their tools broke and the tree trunks had to be blasted out of the ground with gunpowder. The primitive huts built for the officers and officials quickly collapsed in rainstorms. The marines had a habit of not guarding the convicts properly, whilst their commander, Major Robert Ross , drove Phillip to despair with his arrogant and lazy attitude. Crucially, Phillip worried that his fledgling colony was exposed to attack from those described as "Aborigines" or from foreign powers. Although his initial instructions were to establish the colony at Botany Bay, he was authorised to establish the colony elsewhere if necessary.

On 21 January, Phillip and a party which included John Hunter, departed the Bay in three small boats to explore other bays to the north. Phillip discovered that Port Jackson , about 12 kilometres to the north, was an excellent site for a colony with sheltered anchorages, fresh water and fertile soil. Cook had seen and named the harbour, but had not entered it. Phillip's impressions of the harbour were recorded in a letter he sent to England later: "the finest harbour in the world, in which a thousand sail of the line may ride in the most perfect security ...". The party returned to Botany Bay on 23 January.

On the morning of 24 January, the party was startled when two French ships, the Astrolabe and the Boussole , were seen just outside Botany Bay. This was a scientific expedition led by Jean-François de La Pérouse . The French had expected to find a thriving colony where they could repair ships and restock supplies, not a newly arrived fleet of convicts considerably more poorly provisioned than themselves. There was some cordial contact between the French and British officers, but Phillip and La Pérouse never met. The French ships remained until 10 March before setting sail on their return voyage. They were not seen again and were later discovered to have been shipwrecked off the coast of Vanikoro in the present-day Solomon Islands .

On 26 January 1788, the Fleet weighed anchor and sailed to Port Jackson . The site selected for the anchorage had deep water close to the shore, was sheltered, and had a small stream flowing into it. Phillip named it Sydney Cove , after Lord Sydney , the British Home Secretary . This date is celebrated as Australia Day , marking the beginning of British settlement. Contrary to popular belief, the British flag was not officially planted until 7 February 1788 when possession was formally proclaimed. There was, as always, a British naval ensign erected at the site of the military encampment, and this had been performed on the evening of 25 January 1788 in a small ceremony conducted by Phillip and some officers and marines from Supply , with the remainder of Supply ' s crew and the convicts observing from on board ship. The remaining ships of the Fleet did not arrive at Sydney Cove until later that day.

The First Fleet encountered Indigenous Australians when they landed at Botany Bay . The Cadigal people of the Botany Bay area witnessed the Fleet arrive and six days later the two ships of French explorer La Pérouse , the Astrolabe and the Boussole , sailed into the bay. When the Fleet moved to Sydney Cove seeking better conditions for establishing the colony, they encountered the Eora people, including the Bidjigal clan. A number of the First Fleet journals record encounters with Aboriginal people.

Although the official policy of the British Government was to establish friendly relations with Aboriginal people, and Arthur Phillip ordered that the Aboriginal people should be well treated, it was not long before conflict began . The colonists did not sign treaties with the original inhabitants of the land. Between 1790 and 1810, Pemulwuy of the Bidjigal clan led the local people in a series of attacks against the colonists.

The ships of the First Fleet mostly did not remain in the colony. Some returned to England, while others left for other ports. Some remained at the service of the Governor of the colony for some months: some of these were sent to Norfolk Island where a second penal colony was established.

- 15 February – HMS Supply sails for Norfolk Island carrying a small party to establish a settlement.

- 5/6 May – Charlotte , Lady Penrhyn and Scarborough set sail for China.

- 14 July – Borrowdale , Alexander , Friendship and Prince of Wales set sail to return to England.

- 2 October – Golden Grove sets sail for Norfolk Island with a party of convicts, returning to Port Jackson 10 November, while HMS Sirius sails for Cape of Good Hope for supplies.

- 19 November – Fishburn and Golden Grove set sail for England. This means that only HMS Supply now remains in Sydney cove.

- 23 December – HMS Guardian carrying stores for the colony strikes an iceberg and is forced back to the Cape. It never reaches the colony in New South Wales.

- 19 March – HMS Sirius is wrecked off Norfolk Island.

- 17 April – HMS Supply sent to Batavia, Dutch East Indies, for emergency food supplies.

- 3 June – Lady Juliana , the first of six vessels of the Second Fleet , arrives in Sydney cove. The remaining five vessels of the Second Fleet arrive in the ensuing weeks.

- 19 September – HMS Supply returns to Sydney having chartered the Dutch vessel Waaksamheyd to accompany it carrying stores.

On Sat 26 January 1842 The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser reported "The Government has ordered a pension of one shilling per diem to be paid to the survivors of those who came by the first vessel into the Colony. The number of these really 'old hands' is now reduced to three, of whom, two are now in the Benevolent Asylum, and the other is a fine hale old fellow, who can do a day's work with more spirit than many of the young fellows lately arrived in the Colony." The names of the three recipients were not given, and is academic as the notice turned out to be false, not having been authorised by the Governor. There were at least 25 persons still living who had arrived with the First Fleet, including several children born on the voyage. A number of these contacted the authorities to arrange their pension and all received a similar reply to the following received by John McCarty on 14 Mar 1842 "I am directed by His Excellency the Governor to inform you, that the paragraph which appeared in the Sydney Gazette relative to an allowance to the persons of the first expedition to New South Wales was not authorised by His Excellency nor has he any knowledge of such an allowance as that alluded to". E. Deas Thomson, Colonial Secretary.

Following is a list of persons known to be living at the time the pension notice was published, in order of their date of death. At this time New South Wales included the whole Eastern seaboard of present day Australia except for Van Diemen's Land which was declared a separate colony in 1825 and achieved self governing status in 1855-6. This list does not include marines or convicts who returned to England after completing their term in NSW and who may have lived past January 1842.

- Rachel Earley: (or Hirley), convict per Friendship and Prince of Wales died 27 April 1842 at Kangaroo Point, VDL (said to be aged 75).

- Roger Twyfield: convict per Friendship died 30 April 1842 at Windsor, aged 98 (NSW reg as Twifield).

- Thomas Chipp: marine private per Friendship died 3 July 1842, buried Parramatta, aged 81 (NSW Reg age 93).

- Anthony Rope: convict per Alexander died 20 April 1843 at Castlereagh NSW, aged 84 (NSW Reg age 89).

- William Hubbard: Hubbard was convicted in the Kingston Assizes in Surrey, England, on 24 March 1784 for theft. He was transported to Australia on Scarborough in the First Fleet. He married Mary Goulding on 19 December 1790 in Rose Hill. In 1803 he received a land grant of 70 acres at Mulgrave Place. He died on 18 May 1843 at the Sydney Benevolent Asylum. His age was given as 76 when he was buried at Christ Church St. Lawrence, Sydney on 22 May 1843.

- Thomas Jones: convict per Alexander died October 1843 in NSW, aged 87.

- John Griffiths: marine private per Friendship who died 5 May 1844 at Hobart, aged 86.

- Benjamin Cusely: marine private per Friendship died 20 June 1845 at Windsor/Wilberforce, aged 86 (said to be 98).

- Henry Kable: convict per Friendship died 16 March 1846 at Windsor, aged 84.

- John McCarty: McCarty was a marine private who sailed on Friendship . McCarty claimed to have been born in Killarney, County Kerry, Ireland, circa Christmas 1745. He first served in the colony of New South Wales, then at Norfolk Island where he took up a land grant of 60 acres (Lot 71). He married first fleet convict Ann Beardsley on Norfolk Island in November 1791 after his marine discharge a month earlier. In 1808, at the impending closure of the Norfolk Island settlement, he resettled in Van Diemen's Land later taking a land grant (80 acres at Herdsman's Cove Melville) in lieu of the one forfeited on Norfolk Island. The last few years of his life were spent at the home of Mr. William H. Budd, at the Kinlochewe Inn near Donnybrook, Victoria. McCarty was buried on local land 24 July 1846, six months past his 100 birthday, although this is very likely an exaggerated age.

- John Alexander Herbert: convict per Scarborough died 19 November 1846 at Westbury Van Diemen's Land, aged 79.

- Robert Nunn: convict per Scarborough died 20 November 1846 at Richmond, aged 86.

- John Howard: convict per Scarborough died 1 January 1847 at Sydney Benevolent Asylum, aged 94.

- John Limeburner: The South Australian Register reported, in an article dated Wednesday 3 November 1847: "John Limeburner, the oldest colonist in Sydney, died in September last, at the advanced age of 104 years. He helped to pitch the first tent in Sydney, and remembered the first display of the British flag there, which was hoisted on a swamp oak-tree, then growing on a spot now occupied as the Water-Police Court. He was the last of those called the 'first-fleeters' (arrivals by the first convict ships) and, notwithstanding his great age, retained his faculties to the last." John Limeburner was a convict on Charlotte . He was convicted on 9 July 1785 at New Sarum, Wiltshire of theft of a waistcoat, a shirt and stockings. He married Elizabeth Ireland in 1790 at Rosehill and together they establish a 50-acre farm at Prospect. He died at Ashfield 4 September 1847 and is buried at St John's, Ashfield, death reg. as Linburner aged 104.

- John Jones: Jones was a marine private on the First Fleet and sailed on Alexander . He is listed in the N.S.W. 1828 Census as aged 82 and living at the Sydney Benevolent Asylum. He is said to have died at the Benevolent Asylum in 1848.

- Jane/Jenny Rose: (nee Jones), child of convict Elizabeth Evans per Lady Penrhyn died 29 August 1849 at Wollongong, aged 71.

- Samuel King: King was a scribbler (a worker in a scribbling mill) before he became a marine. He was a marine with the First Fleet on board Sirius (1786) . He shipped to Norfolk Island on Golden Grove in September 1788, where he lived with Mary Rolt, a convict who arrived with the First Fleet on Prince of Wales . He received a grant of 60 acres (Lot No. 13) at Cascade Stream in 1791. Mary Rolt returned to England on Britannia in October 1796. King was resettled in Van Diemen's Land, boarding City of Edinburgh on 3 September 1808, and landed in Hobart on 3 October. He married Elizabeth Thackery on 28 January 1810. He died on 21 October 1849 at 86 years of age and was buried in the Wesleyan cemetery at Lawitta Road, Back River.

- Mary Stevens: (nee Phillips), convict per Charlotte and Prince of Wales died 22 January 1850 at Longford Van Diemen's Land, aged 81.

- John Small: Convicted 14 March 1785 at the Devon Lent Assizes held at Exeter for Robbery King's Highway. Sentenced to hang, reprieved to 7 years' transportation. Arrived on Charlotte in First Fleet 1788. Certificate of freedom 1792. Land Grant 1794, 30 acre "Small's Farm" at Eastern Farms (Ryde). Married October 1788 Mary Parker also a First Fleet convict who arrived on Lady Penrhyn . John Small died on 2 October 1850 aged 90 years.

- Edward Smith: aka Beckford, convict per Scarborough died 2 June 1851 at Balmain, aged 92.

- Ann Forbes: (m.Huxley), convict per Prince of Wales died 29 December 1851, Lower Portland NSW, aged 83.

- Henry Kable Jnr: aka Holmes, b. 1786 in Norwich Castle prison, son of convict Susannah Holmes per Friendship and Charlotte , died 13 May 1852 at Picton, New South Wales aged 66.

- Lydia Munro: (m.Goodwin) per Prince of Wales died 29 June 1856 at Hobart, reg as Letitia Goodwin, aged 85.

- Elizabeth Thackery: Elizabeth "Betty" King (née Thackery) was tried and convicted of theft on 4 May 1786 at Manchester Quarter Sessions, and sentenced to seven years' transportation. She sailed on Friendship , but was transferred to Charlotte at the Cape of Good Hope. She was shipped to Norfolk Island on Sirius (1786) in 1790 and lived there with James Dodding. In August 1800 she bought 10 acres of land from Samuel King at Cascade Stream. Elizabeth and James were relocated to Van Diemen's Land in December 1807 but parted company sometime afterwards. On 28 January 1810 Elizabeth married "First Fleeter" Private Samuel King (above) and lived with him until his death in 1849. Betty King died in New Norfolk, Tasmania on 7 August 1856, aged 89 years. She is buried in the churchyard of the Methodist Chapel, Lawitta Road, Back River, next to her husband, and the marked grave bears a First Fleet plaque.

- John Harmsworth: marine's child b.1788 per Prince of Wales died 21 July 1860 at Clarence Plains Tasmania, aged 73 years.

Historians have disagreed over whether those aboard the First Fleet were responsible for introducing smallpox to Australia's indigenous population, and if so, whether this was the consequence of deliberate action.

In 1914, J. H. L. Cumpston, director of the Australian Quarantine Service put forward the hypothesis that smallpox arrived in Australia with First Fleet. Some researchers have argued that any such release may have been a deliberate attempt to decimate the indigenous population. Hypothetical scenarios for such an action might have included: an act of revenge by an aggrieved individual, a response to attacks by indigenous people, or part of an orchestrated assault by the New South Wales Marine Corps, intended to clear the path for colonial expansion. Seth Carus, a former Deputy Director of the National Defense University in the United States wrote in 2015 that there was a "strong circumstantial case supporting the theory that someone deliberately introduced smallpox in the Aboriginal population."

Other historians have disputed the idea that there was a deliberate release of smallpox virus and/or suggest that it arrived with visitors to Australia other than the First Fleet. It has been suggested that live smallpox virus may have been introduced accidentally when Aboriginal people came into contact with variolous matter brought by the First Fleet for use in anti-smallpox inoculations.

In 2002, historian Judy Campbell offered a further theory, that smallpox had arrived in Australia through contact with fishermen from Makassar in Indonesia, where smallpox was endemic. In 2011, Macknight stated: "The overwhelming probability must be that it [smallpox] was introduced, like the later epidemics, by [Indonesian] trepangers ... and spread across the continent to arrive in Sydney quite independently of the new settlement there."

There is a fourth theory, that the 1789 epidemic was not smallpox but chickenpox – to which indigenous Australians also had no inherited resistance – that happened to be affecting, or was carried by, members of the First Fleet. This theory has also been disputed.

After Ray Collins, a stonemason, completed years of research into the First Fleet, he sought approval from about nine councils to construct a commemorative garden in recognition of these immigrants. Liverpool Plains Shire Council was ultimately the only council to accept his offer to supply the materials and construct the garden free of charge. The site chosen was a disused caravan park on the banks of Quirindi Creek at Wallabadah, New South Wales . In September 2002 Collins commenced work on the project. Additional support was later provided by Neil McGarry in the form of some signs and the council contributed $28,000 for pathways and fencing. Collins hand-chiselled the names of all those who came to Australia on the eleven ships in 1788 on stone tablets along the garden pathways. The stories of those who arrived on the ships, their life, and first encounters with the Australian country are presented throughout the garden. On 26 January 2005, the First Fleet Garden was opened as the major memorial to the First Fleet immigrants. Previously the only other specific memorial to the First Fleeters was an obelisk at Brighton-Le-Sands, New South Wales . The surrounding area has a barbecue, tables, and amenities.

First Fleet Park is situated in The Rocks , near the site of the First Fleet's landing. The area has remained in public ownership continually since 1788, under the control of various agencies. It was previously used for a hospital, Queen's Wharf, shops and houses, the first Commissariat Store and the first post office. Archaeological remains are extant on the site dating back to the earliest days of settlement.

- James Talbot, The Thief Fleet , 2012, ISBN : 978-1-4699148-2-4

- Colleen McCullough , Morgan's Run , ISBN : 0-09-928098-1

- Timberlake Wertenbaker, Our Country's Good , ISBN : 0-413-73740-3

- Thomas Keneally , The Playmaker , ISBN : 0-340-42263-7

- William Stuart Long, The Exiles , ISBN : 978-0-8398-2824-2 (hardcover, 1984) ISBN : 978-0-440-12369-9 (paperback, 1979) ISBN : 978-0-440-12374-3 (mass market paperback, 1981)

- William Stuart Long, The Settlers , ISBN : 978-0-86824-020-6 (hardcover, 1980) ISBN : 978-0-440-15923-0 (paperback, 1980) ISBN : 978-0-440-17929-0 (mass market paperback, 1982)

- William Stuart Long, The Traitors , ISBN : 978-0-8398-2826-6 (hardcover, 1984) ISBN : 978-0-440-18131-6 (mass market paperback, 1981)

- D. Manning Richards, Destiny in Sydney: An epic novel of convicts, Aborigines, and Chinese embroiled in the birth of Sydney, Australia , ISBN : 978-0-9845410-0-3

- Marcus Clarke , For the Term of his Natural Life. Melbourne, 1874

- Australian frontier wars

- Convicts in Australia

- Convict women in Australia

- European exploration of Australia

- History of Australia (1788–1850)

- History of Indigenous Australians

- Journals of the First Fleet

- Penal transportation

- Prehistory of Australia

- Second Fleet (Australia)

- Terra nullius

- Third Fleet (Australia)

- Banished (TV series) - a short-lived 2015 dramatisation

- This page was last modified on 10 June 2024, at 09:55. Suggest an edit .

Pursuit home

- All sections

The First Fleet and Australia’s unforgiving weather

Passengers onboard the First Fleet received a harsh introduction to their new home’s climate before they even landed. Their diaries and letters reveal just how hard it was

By Dr Joëlle Gergis, University of Melbourne

The women screamed as the huge waves crashed loudly on the wooden deck. Horrified, they watched the foaming torrent wash away their blankets. Many dropped to their knees, praying for the violent rocking to stop. The sea raged around them as the wind whipped up into a frenzy, damaging all but one of the heavily loaded ships.

The severe storm was yet another taste of the ferocious weather that slammed the First Fleet as it made its way across the Southern Ocean in December 1787. Now, after an eight-month journey from England in a ship riddled with death and disease, the passengers’ introduction to Australia was also far from idyllic.

The unforgiving weather that greeted the First Fleet was a sign of things to come. More than once, intense storms would threaten the arrival of the ships and bring the new colony close to collapse.

So how did the early arrivals to Australia deal with such extreme weather? Have we always had a volatile climate? To answer these questions, we need to follow Australia’s colonial settlers back beyond their graves and trace through centuries-old documents to uncover what the climate was like from the very beginning of European settlement.

Restoring one of the world's rarest maps

By poking around in the settlers’ old diaries, letters and newspaper clippings, we can begin to piece together an idea of what the country’s climate was like long before official weather measurements began.

When the British sailed into Australian waters, they had no idea of what awaited them. Perhaps they expected that life would resemble their other colonial outposts like India, or an undeveloped version of England. With enough hard work, surely the land could be tamed to support their needs.

But when the First Fleet sailed into Sydney Cove, they unknowingly entered an ancient landscape with an unforgiving climate.

Even before Governor Arthur Phillip set foot in Botany Bay, violent storms had battered the overcrowded ships of the First Fleet. During the final eight-week leg of the journey from Cape Town to Botany Bay, the ships had sailed into the westerly winds and tremendous swells of the Southern Ocean. Ferocious weather hit the First Fleet as it made its way through the roaring forties in November–December 1787.

Although the strong westerlies were ideal for sailing, conditions on the ships were miserable. Lieutenant Philip Gidley King described the difficult circumstances on board HMS Supply : ‘Very strong gales … with a very heavy sea running which keeps this vessel almost constantly under water and renders the situation of everyone on board her, truly uncomfortable’. Unable to surface on deck in the rough seas, the convicts remained cold and wet in the cramped holds.

Captain John Hunter described how the rough seas made life on the Sirius very difficult for the animals on board:

The rolling and labouring of our ship exceedingly distressed the cattle, which were now in a very weak state, and the great quantities of water which we shipped during the gale, very much aggravated their distress. The poor animals were frequently thrown with much violence off their legs and exceedingly bruised by their falls.

How a quest for the past found a living present

It wasn’t until the first week of January 1788 that the majority of the First Fleet sailed past the south-eastern corner of Van Diemen’s Land, modern-day Tasmania. As his boat navigated the coast, surgeon John White noted: ‘We were surprised to see, at this season of the year, some small patches of snow’.

According to Bowes Smyth, faced with a ‘greater swell than at any other period during the voyage’, many of the ships were damaged, as were seedlings needed to supply the new colony with food. Bowes Smyth continued:

The sky blackened, the wind arose and in half an hour more it blew a perfect hurricane, accompanied with thunder, lightening and rain … I never before saw a sea in such a rage, it was all over as white as snow … every other ship in the fleet except the Sirius sustained some damage … during the storm the convict women in our ship were so terrified that most of them were down on their knees at prayers.

Finally, on 19 January, the last ships of the First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay. But after just three days there, Phillip realised that the site was unfit for settlement. It had poor soil, insufficient freshwater supplies, and was exposed to strong southerly and easterly winds.

With all the cargo and 1400 starving convicts still anchored in Botany Bay, Phillip and a small party, including Hunter, quickly set off in three boats to find an alternative place to settle. Twelve kilometres to the north they found Port Jackson.

On 23 January 1788, Phillip and his party returned to Botany Bay and gave orders for the entire fleet to immediately set sail for Port Jackson. But the next morning, strong headwinds blew, preventing the ships from leaving the harbour. A huge sea rolling into the bay caused ripped sails and a lost boom as the ships drifted dangerously close to the rocky coastline. According to Lieutenant Ralph Clark:

The Irish Rising that shaped Australia

If it had not been by the greatest good luck, we should have been both on the shore [and] on the rocks, and the ships must have been all lost, and the greater part, if not the whole on board drowned, for we should have gone to pieces in less than half of an hour.

By 3 p.m. on 26 January 1788, all eleven ships of the First Fleet had safely arrived in Port Jackson. Meanwhile, while waiting for the others to arrive, Phillip and a small party from the Supply had rowed ashore and planted a Union Jack, marking the beginning of European settlement in Australia.

After such an epic journey, the whole ordeal was washed away with swigs of rum. Unknowingly, it marked the start of our rocky relationship with one of the most volatile climates on Earth.

This is an edited extract from Joelle Gergis’s Sunburnt Country: The History and Future of Climate Change in Australia , out 2 April from Melbourne University Press. RRP $34.99, Ebook $16.99, from mup.com.au and all good bookstores.

This article has been co-published with The Conversation .

Banner image: The H.M. Bark Endeavour, part of Captain Cook’s first voyage of discovery to Australia and New Zealand from 1769 to 1771, Oswald Brett

First Fleet Timeline

Leaving england.

Last Sight of England

Reaching the Canary Islands

Departing the Canary Islands

Passing Cape Verde Islands

Crossing the Equator

Islands of Rio de Janeiro in Sight

Docks at Rio de Janeiro

Departs Rio de Janeiro

Cape of Good Hope sighted

Anchors in Table Bay for supplies

Departs Table Bay

The Advance Party

Sighting Van Diemen's Land

HMS Supply arrives in Botany Bay

Entire Fleet arives at Botany Bay

Captain Phillip and Captain Hunter go to the North

Entire Fleet anchors in Port Jackson

- Transition Guide (Opens in new window)

- Subscribe Now (Opens in new window)

Your Military

- Army Times (Opens in new window)

- Navy Times (Opens in new window)

- Air Force Times (Opens in new window)

- Marine Corps Times (Opens in new window)

- Pentagon & Congress

- Defense News (Opens in new window)

- Israel-Palestine

- Extremism & Disinformation

- Afghanistan

- Benefits Guide (Opens in new window)

- Family Life

- Military Pay Center

- Military Retirement

- Military Benefits

- Discount Depot

- Gear Scout (Opens in new window)

- Military Culture

- Military Fitness

- Military Movies & Video Games

- Military Sports

- Military Communities

- Pay It Forward (Opens in new window)

- Military History

- Salute to Veterans

- Black Military History

- Congressional Veterans Caucus (Opens in new window)

- Military Appreciation Month

- Vietnam Vets & Rolling Thunder

- Service Members of the Year (Opens in new window)

- World War I

- Honor the Fallen (Opens in new window)

- Hall of Valor (Opens in new window)

- Create an Obituary (Opens in new window)

- Medals & Misfires

- Installation Guide (Opens in new window)

- Battle Bracket

- America's Military

- Task Force Violent

- CFC Givers Guide

- Newsletters (Opens in new window)

- Early Bird Brief

- MCON (Opens in new window)

- Long-Term Care Partners

- Navy Federal

A timeline of the US-built Gaza pier and the challenges it’s faced

A string of security, logistical and weather problems has battered the plan to deliver desperately needed humanitarian aid to Gaza through a U.S. military-built pier .

Broken apart by strong winds and heavy seas just over a week after it became operational, the project faces criticism that it hasn’t lived up to its initial billing or its $320 million price tag.

Military’s novel floating pier arrives in Gaza amid security concerns

The gaza aid pier is made possible by an oft-neglected but vital military capability known as joint logistics over-the-shore, or jlots..

U.S. officials say, however, that the steel causeway connected to the beach in Gaza and the floating pier are being repaired and reassembled at a port in southern Israel, then will be reinstalled and working again next week.

While early Pentagon estimates suggested the pier could deliver up to 150 truckloads of aid a day when in full operation, that has yet to happen . Bad weather has hampered progress getting aid into Gaza from the pier, while the Israeli offensive in the southern city of Rafah has made it difficult, if not impossible at times, to get aid into the region by land routes.

Aid groups have had mixed reactions — both welcoming any amount of aid for starving Palestinians besieged by the nearly eight-month-old Israel-Hamas war and decrying the pier as a distraction that took pressure off Israel to open more border crossings, which are far more productive.

It’s “a side-show,” said Bob Kitchen, a top official of the International Rescue Committee.

The Biden administration has said from the start that the pier wasn’t meant to be a total solution and that any amount of aid helps.

“Nobody said at the outset that it was going to be a panacea for all the humanitarian assistance problems that still exist in Gaza,” national security spokesman John Kirby said Wednesday. “I think sometimes there’s an expectation of the U.S. military — because they’re so good — that everything that they touch is just going to turn to gold in an instant.”

“We knew going in that this was going to be tough stuff,” he added. “And it has proven to be tough stuff.”

Before the war, Gaza was getting about 500 truckloads of aid on average every day. The United States Agency for International Development says it needs a steady flow of 600 trucks a day to ease the struggle for food and bring people back from the brink of famine .

The aid brought through the pier was enough to feed thousands for a month, but U.N. data shows it barely made a dent in the overall need of Gaza’s 2.3 million people.

Here’s a look at the timeline of the pier, the problems it faced and what may come next:

March: Announcement and prep

March 7: President Joe Biden announces his plan for the U.S. military to build a pier during his State of the Union address.

“Tonight, I’m directing the U.S. military to lead an emergency mission to establish a temporary pier in the Mediterranean on the coast of Gaza that can receive large shipments carrying food, water, medicine and temporary shelters,” he said.

But even in those first few moments, he noted the pier would increase the amount of humanitarian aid getting into Gaza but that Israel “must do its part” and let more aid in.

March 8: Maj. Gen. Pat Ryder, Pentagon spokesman, tells reporters it will take “up to 60 days” to deploy the forces and build the project.

March 12: Four U.S. Army boats loaded with tons of equipment and steel pier segments leave Joint Base Langley-Eustis in Virginia and head to the Atlantic Ocean for what is expected to be a monthlong voyage to Gaza.

The brigade’s commander, Army Col. Sam Miller, warns that the transit and construction will be heavily dependent on the weather and any high seas they encounter.

Late March: U.S. Army vessels hit high seas and rough weather as they cross the Atlantic, slowing their pace.

April: Construction and hope

April 1: Seven World Central Kitchen aid workers are killed in an Israeli airstrike as they travel in clearly marked vehicles on a delivery mission authorized by Israel.

The strike fuels ongoing worries about security for relief workers and prompts aid agencies to pause delivery of humanitarian assistance in Gaza.

April 19: U.S. officials confirm that the U.N. World Food Program has agreed to help deliver aid brought to Gaza via the maritime route once construction is done.

April 25: Major construction of the port facility on the shore near Gaza City begins to take shape. The onshore site is where aid from the causeway will be delivered and given to aid agencies.

April 30: Satellite photos show the U.S. Navy ship USNS Roy P. Benavidez and Army vessels working on assembling the pier and causeway about 6.8 miles from the port on shore.

May: The pier opens … then closes

May 9: The U.S. vessel Sagamore is the first ship loaded with aid to leave Cyprus and head toward Gaza and ultimately the pier. An elaborate security and inspection station has been built in Cyprus to screen the aid coming from a number of countries.

May 16: Well past the 60-day target time, the construction and assembly of the pier off the Gaza coast and the causeway attached to the shoreline are finished after more than a week of weather and other delays.

May 17: The first trucks carrying aid for the Gaza Strip roll down the newly built pier and into the secure area on shore, where they will be unloaded and the cargo distributed to aid agencies for delivery by truck into Gaza.

May 18: Crowds of desperate Palestinians overrun a convoy of aid trucks coming from the pier, stripping the cargo from 11 of the 16 vehicles before they reach a U.N. warehouse for distribution.

May 19-20: The first food from the pier — a limited number of high-nutrition biscuits — reaches people in need in central Gaza, according to the World Food Program.

Aid organizations suspend deliveries from the pier for two days while the U.S. works with Israel to open alternate land routes from the pier and improve security.

May 24: So far, a bit more than 1,000 metric tons of aid has been delivered to Gaza via the U.S.-built pier, and USAID later says all of it has been distributed within Gaza.

May 25: High winds and heavy seas damage the pier and cause four U.S. Army vessels operating there to become beached, injuring three service members, including one who is in critical condition.

Two vessels went aground in Gaza near the base of the pier and two went aground near Ashkelon in Israel.

May 28: Pentagon spokeswoman Sabrina Singh says large portions of the causeway are being pulled from the beach and moved to an Israeli port for repairs. The base of the causeway remains at the Gaza shore.

She also says that aid in Cyprus is being loaded onto vessels and will be ready to unload onto the pier once it is back in place.

May 29: Two of the Army vessels that ran aground in the bad weather are now back at sea and the other two near the pier are being freed, with the aid of the Israeli navy.

What’s next?

In the coming days, the sections of the causeway will be put back together, and by the middle of next week will be moved back to the Gaza shore, where the causeway will once again be attached to the beach, the Pentagon says.