The Ages of Exploration

Age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

Chinese explorer who commanded several treasure fleets – Chinese ships that explored and traded across Asia and Africa. His expeditions greatly expanded China’s trade.

Name : Zheng He [jung] [ha]

Birth/Death : 1371 - 1433

Nationality : Chinese

Birthplace : China

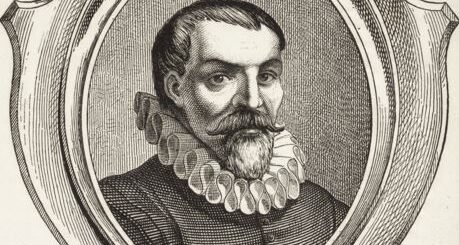

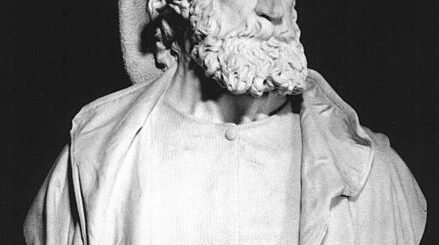

Zheng He Statue

General Zheng He - statue in Sam Po Kong temple, Semarang, Indonesia. (Credit: en.wiki 22Kartika)

Introduction Zheng He was a Chinese explorer who lead seven great voyages on behalf of the Chinese emperor. These voyages traveled through the South China Sea, Indian Ocean, Arabian Sea, Red Sea, and along the east coast of Africa. His seven total voyages were diplomatic, military, and trading ventures, and lasted from 1405 – 1433. However, most historians agree their main purpose was to promote the glory of Ming dynasty China. 1

Biography Early Life Zheng He was born to a noble family in 1371 in the Yunnan Province of China. His father was named Haji Ma, and his mother’s maiden name was “Wen”. Ma He had one older brother, and four sisters. 2 His family was Muslim, so when he was born, he was originally named “Ma He.” Ma is the Chinese version of Mohammed, who was the great prophet of the Islamic faith. 3 His father and grandfather were highly respected in their community. Young Ma He was educated as a child, often reading books from great scholars such as Confucius and Mencius. 4 Ma He was curious about the world from a young age. In Islam, Muslim believers are supposed to make a pilgrimage, called a hajj in Arabic, to the Muslim holy city of Mecca (in present day Saudi Arabia). Ma He’s father and grandfather had both made this hajj, so Ma He often them questions of their journey, along with the people and places they encountered. In 1381, when Ma He was about 11 years old, Yunnan was attacked and conquered by soldiers from the Ming army, who were under the rule of Emperor Hong Wu. Ma He, like many children, were taken captive and brought to serve as a eunuch in the Ming Court.

While serving in the royal court, the Emperor had noticed that Ma He was a hardworking boy. Ma He received military training, and soon became a trusted assistant and adviser to the emperor. He also served as a bodyguard protecting the prince Zhu Di during many battles against the Mongols. Shortly after, Zhu Di became emperor of the Ming Dynasty. Having served in the court for many years, Ma He was eventually promoted to Grand Eunuch.This was the highest rank a eunuch could be promoted to. Because of his new and higher position, the Emperor gave Ma He the new name “Zheng” He. 5 With his new title came additional duties Zheng He would be responsible for. He would be in charge of palace construction and repairs, learned more about weapons, and became more knowledgeable in ship construction. 6 His understanding of ships would become very important to his future. In 1403, Zhu Di, ordered the construction of the Treasure Fleet – a fleet of trading ships, warships and support vessels. This fleet was to travel across the South China Sea and Indian Ocean areas. The Emperor chose Zheng He to command this fleet. He would be the official ambassador of the imperial court to foreign countries. This would begin Zheng He’s maritime career, and some of the most impressive exploration journeys in history.

Voyages Principal Voyage Zheng He’s first voyage (1405-1407) began in July 1405. They set sail from Liujiagan Port in Taicang of Jiangsu Province and headed westward. The fleet had about 208 vessels total, including 62 Treasure Ships, and more than 27,800 crewman. 7 They traveled to present day Vietnam. Here, they met with the king and presented him with gifts. The King was pleased with Zheng He and the emperor’s kind gesture, and the visit was a friendly one. After leaving, the fleet traveled to Java, Sumatra; Malacca (the Spice Islands); crossed the Indian Ocean and sailed west to Cochin and Calicut, India. The many stops included trading of spices and other goods, plus visiting royal courts and building relations on behalf of the Chinese emperor. He also saw several new animals, which he told the emperor about upon his return. Zheng He’s first voyage ended when he returned to China in 1407.

Zheng He’s second (1408-1409) and third (1409-1411) voyages followed a similar route to his first. Once again he stopped in places like Java, Sumatra; and visited ports on the coast of Siam (today called Thailand) and the Malay Peninsula. 8 Zheng He’s fourth voyage (1413-1415) would be his most impressive yet. The Chinese Emperor really wanted to display the wealth and power China had to offer. With 63 large ships, and a crew of over 27,000 men, Zheng He set sail. Once more he sailed to the Malay Peninsula, to Sri Lanka, and on to Calicut in India. Instead of staying at Calicut as he had on previous voyages, Zheng He and his fleet also sailed to the Maldive and Laccadive Islands to the Hormuz on the Persian Gulf. 9 Along the way, they traded goods like silk and spices with rulers of other countries. He returned to Nanjing in 1415. He also brought back with him several envoys or representatives of various countries for the emperor to meet with and learn from.

Subsequent Voyages By 1417, the Yongle Emperor ordered Zheng He to return the envoys home. Once more back on the seas, Zheng He and his large fleet set sail for his fifth expedition (1417-1419). He stopped in many of the same places, including Java, Sumatra, and also brought letters and riches to the different rulers Zheng He met. On this trip, Zheng He sailed into new waters, to the Somali coast and down to Kenya, both in Africa. He returned back to China in 1419. Zheng He’s sixth voyage (1421-1422) was his shortest of them all. He was authorized to return the remaining envoy’s to their home countries. Not only did he revist many of the ports he’d been to many times, but also went back to the Mogadishu region of Somalia. He also visited Thailand, before making his way back to China in September 1422. By the time he returned, the emperor had died. The new emperor suspended all expeditions. Zheng He remained in the royal court working for the new emperor, helping with the construction of a large temple. But would be almost another 10 years before Zheng He went on his seventh and final voyage.

Later Years and Death It was not until 1431 that Zheng He found himself in command of the large Treasure Fleet for his seventh voyage (1431-1433). They sailed to Java, Sumatra and several other Asian ports before arriving in Calicut, India. During this trip, Zheng He temporarily split from the fleet and made his hajj to the Muslim holy city of Mecca. 10 At some point, Zheng He fell ill, and died in 1433. It is not known whether or not he made it back to China, or died on his final great voyage.

Legacy Zheng He’s voyages to western oceans expanded China’s political influence in the world. He was able to expand new, friendly ties with other nations, while developing relations between the east-west trade opportunities. Unfortunately, the official imperial records of his voyages were destroyed. The exact purpose of his voyages, the routes taken, and the size of his fleets are heavily debated because of their unique nature. 11 Nonetheless, his leadership and principles have remained known over the centuries in Chinese history. July 11 is celebrated as China’s National Maritime Day commemorating his first voyage.

- Leo Suryadinata, ed., Admiral Zheng He & Southeast China (Pasir Panjang, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2005), 44.

- Hum Sin Hoon, Zheng He’s Art of Collaboration: Understanding the Legendary Chinese Admiral from a Management Perspective (Pasir Panjang, Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2012), 6.

- Hoon, Zheng He’s Art of Collaboration, 6.

- Hoon, Zheng He’s Art of Collaboration, 7.

- Information Office of the People’s Government of Fujian Province, Zheng He’s Voyages Down the Western Seas (China: China Intercontinental Press, 2005), 8.

- Shih-shan Henry Tsai, The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 157.

- Information Office of the People’s Government of Fujian Province, Zheng He’s Voyages Down the Western Seas, 22.

- Brian Fagan, Beyond the Blue Horizon: How the Earliest Mariners Unlocked the Secrets of the Oceans (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2012), 157.

- Fagan, Beyond the Blue Horizon, 158.

- Fagan, Beyond the Blue Horizon, 162.

- Richard E. Bohlander, ed., World Explorers and Discoverers (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1992), 466.

Bibliography

Bohlander, Richard E., ed. World Explorers and Discoverers. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1992.

Fagan, Brian. Beyond the Blue Horizon: How the Earliest Mariners Unlocked the Secrets of the Oceans. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2012.

Hoon, Hum Sin. Zheng He’s Art of Collaboration: Understanding the Legendary Chinese Admiral from a Management Perspective. Pasir Panjang, Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2012.

Information Office of the People’s Government of Fujian Province, Zheng He’s Voyages Down the Western Seas. China: China Intercontinental Press, 2005.

Suryadinata, Leo ed. Admiral Zheng He & Southeast China. Pasir Panjang, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2005.

Tsai, Shih-shan Henry. The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

Premium Content

- HISTORY MAGAZINE

China’s greatest naval explorer sailed his treasure fleets as far as East Africa

Spreading Chinese goods and prestige, Zheng He commanded seven voyages that established China as Asia's strongest naval power in the 1400s.

Perhaps it is odd that China’s greatest seafarer was raised in the mountains. The future admiral Zheng He was born around 1371 to a family of prosperous Muslims. Then known as Ma He, he spent his childhood in Mongol-controlled, landlocked Yunnan Province, located several months’ journey from the closest port. When Ma He was about 10 years old, Chinese forces invaded and overthrew the Mongols ; his father was killed, and Ma He was taken prisoner. It marked the beginning of a remarkable journey of shifting identities that this remarkable man would navigate.

Many young boys taken from the province were ritually castrated and then brought to serve in the court of Zhu Di, the future Ming emperor or Yongle. Over the next decade, Ma He would distinguish himself in the prince’s service and rise to become one of his most trusted advisers. Skilled in the arts of war, strategy, and diplomacy, the young man cut an imposing figure: Some described him as seven feet tall with a deep, booming voice. Ma He burnished his reputation as a military commander with his feats at the battle of Zhenglunba, near Beijing. After Zhu Di became the Yongle emperor in 1402, Ma He was renamed Zheng He in honor of that battle. He continued to serve alongside the emperor and became the commander of China’s most important asset: its great naval fleet, which he would command seven times.

China on the high seas

Zheng He’s voyages followed in the wake of many centuries of Chinese seamanship. Chinese ships had set sail from the ports near present-day Shanghai, crossing the East China Sea, bound for Japan. The vessels’ cargo included material goods, such as rice, tea, and bronze, as well as intellectual ones: a writing system, the art of calligraphy, Confucianism , and Buddhism.

As far back as the 11th century, multi-sailed Chinese junks boasted fixed rudders and watertight compartments—an innovation that allowed partially damaged ships to be repaired at sea. Chinese sailors were using compasses to navigate their way across the South China Sea. Setting off from the coast of eastern China with colossal cargoes, they soon ventured farther afield, crossing the Strait of Malacca while seeking to rival the Arab ships that dominated the trade routes in luxury goods across the Indian Ocean—or the Western Ocean, as the Chinese called it.

While a well-equipped navy had been built up during the early years of the Song dynasty (960- 1279), it was in the 12th century that the Chinese became a truly formidable naval power. The Song lost control of northern China in 1127, and with it, access to the Silk Road and the wealth of Persia and the Islamic world. The forced withdrawal to the south prompted a new capital to be established at Hangzhou, a port strategically situated at the mouth of the Qiantang River, and which Marco Polo described in the course of his famous adventures in the 1200s. ( See pictures from along Marco Polo's journey through Asia. )

For centuries, the Song had been embroiled in battles along inland waterways and had become indisputable masters of river navigation. Now, they applied their experience to building up a naval fleet. Alas, the Song’s newfound naval mastery was not enough to withstand the invasion of the mighty Mongol emperor Kublai Khan. ( Kublai Khan achieved what Genghis could not: conquering China .)

Kublai Khan kamikazed

Kublai Khan built an empire for the Mongols in the 13th century, conquering China in 1279. He also had his sights set on Japan and tried to invade, not once, but twice: first in 1274 and again in 1281. Chroniclers of the time report that he sent thousands of Chinese and Korean ships and as many as 140,000 men to seize the islands of Japan. Twice his massive forces sailed across the Korea Strait, and twice his fleet was turned away; legend says that two kamikazes, massive typhoons whose name means “divine wind,” were summoned by the Japanese emperor to sink the invading vessels. Historians believed the stories to be legendary, but recent archaeological finds support the story of giant storms saving Japan.

The Mongols and the Ming

Having toppled the Song and ascended to the Chinese imperial throne in 1279, Kublai built up a truly fearsome naval force. Millions of trees were planted and new shipyards created. Soon, Kublai commanded a force numbering thousands of ships, which he deployed to attack Japan, Vietnam, and Java. And while these naval offensives failed to gain territory, China did win control over the sea-lanes from Japan to Southeast Asia. The Mongols gave a new preeminence to merchants, and maritime trade flourished as never before.

For Hungry Minds

On land, however, they failed to establish a settled form of government and win the allegiance of the peoples they had conquered. In 1368, after decades of internal rebellion throughout China, the Mongol dynasty fell and was replaced by the Ming (meaning “bright”) dynasty. Its first emperor, Hongwu, was as determined as the Mongol and Song emperors before him to maintain China as a naval power. However, the new emperor limited overseas contact to naval ambassadors who were charged with securing tribute from an increasingly long list of China’s vassal states, among them, Brunei, Cambodia, Korea, Vietnam, and the Philippines, thus ensuring that lucrative profits did not fall into private hands. Hongwu also decreed that no oceangoing vessels could have more than three masts, a dictate punishable by death. ( The Ming Dynasty built the Great Wall. Find out if it worked. )

Yongle was the third Ming emperor, and he took this restrictive maritime policy even further, banning private trade while pushing hard for Chinese control of the southern seas and the Indian Ocean. The beginning of his reign saw the conquest of Vietnam and the foundation of Malacca as a new sultanate controlling the entry point to the Indian Ocean, a supremely strategic location for China to control. In order to dominate the trade routes that united China with Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, the emperor decided to assemble an impressive fleet, whose huge treasure ships could have as many masts as necessary. The man he chose as its commander was Zheng He.

Epic voyages

Although he is often described as an explorer, Zheng He did not set out primarily on voyages of discovery. During the Song dynasty, the Chinese had already reached as far as India, the Persian Gulf, and Africa. Rather, his voyages were designed as a display of Chinese might, as well as a way of rekindling trade with vassal states and guaranteeing the flow of vital provisions, including medicines, pepper, sulfur, tin, and horses.

The fleets that Zheng He commanded on his seven great expeditions between 1405 and 1433 were suitably ostentatious. On the first voyage, the fleet numbered 255 ships, 62 of which were vast treasure ships, or baochuan. There were also mid-size ships such as the machuan, used for transporting horses, and a multitude of other vessels carrying soldiers, sailors, and assorted personnel. Some 600 officials made the voyage, among them doctors, astrologers, and cartographers.

The ships left Nanjing (Nanking), Hangzhou, and other major ports, from there veering south to Fujian, where they swelled their crews with expert sailors. They then made a show of force by anchoring in Quy Nhon, Vietnam , which China had recently conquered. None of the seven expeditions headed north; most made their way to Java and Sumatra, resting for a spell in Malacca, where they waited for the winter monsoon winds that blow toward the west.

You May Also Like

She was Genghis Khan’s wife—and made the Mongol Empire possible

Meet 5 of history's most elite fighting forces

Kublai Khan did what Genghis could not—conquer China

They then proceeded to Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) and Calicut in southern India, where the first three expeditions terminated. The fourth expedition reached Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, and the final voyages expanded westward, entering the waters of the Red Sea, then turning and sailing as far as Kenya, and perhaps farther still. A caption on a copy of the Fra Mauro map —the original, now lost, was completed in Venice in 1459, more than 25 years after Zheng He’s final voyage—implies that Chinese ships rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1420 before being forced to turn back for lack of wind.

Treasure ships were the largest vessels in Zheng He’s fleet. A description of them appears in adventure novel by Luo Maodeng, The Three-Treasure Eunuch’s Travels to the Western Ocean (1597). The author writes that the ships had nine masts and measured 460 feet long and 180 feet wide. It is hard to believe that the ships would have been quite so vast. Authorities on Zheng He’s maritime expeditions believe the vessels more likely had five or six masts and measured 250 to 300 feet long.

Chinese ships had always been noted for their size. More than a century before Zheng He, explorer Marco Polo described their awesome dimensions: Between four and six masts, a crew of up to 300 sailors, 60 cabins, and a deck for the merchants. Chinese vessels with five masts are shown on the 14th-century “Catalan Atlas” from the island of Mallorca. Still, claims in a 1597 adventure tale that Zheng He’s treasure ships reached 460 feet long do sound exaggerated. Most marine archaeological finds suggest that Chinese ships of the 14th and 15th centuries usually were not longer than 100 feet. Even so, a recent discovery by archaeologists of a 36-foot-long rudder raises the possibility that some ships may have been as large as claimed. (A 1,200-year-old shipwreck reveals how the world traded with China.)

Ma Huan's true tall tales

Of the three chroniclers who recorded Zheng He’s voyages, Ma Huan was perhaps the most reliable. Of humble origins, Ma Huan converted to Islam as a young man and studied Arabic and Persian. At age 23 he served as an interpreter for the fourth expedition. He served on the sixth and seventh voyages as well. In East Africa Ma Huan first saw what he called a qilin —the Chinese word for a unicorn-like creature—evidently a giraffe: ”The head is carried on a long neck over 16 feet long,” he noted, with some exaggeration. “On its head it has two fleshy horns. It has the tail of an ox and the body of a deer...and it eats unhusked rice, beans and flour cakes.”

End of an odyssey

Zheng He’s voyages ended abruptly in 1433 on the command of Emperor Xuande. Historians have long speculated as to why the Ming would have abandoned the naval power that China had nurtured since the Song. The problems were certainly not economic: China was collecting enormous tax revenues, and the voyages likely cost a fraction of that income.

The problem, it seems, was political. The Ming victory over the Mongols caused the empire’s focus to shift from the ports of the south to deal with tensions in the north. The voyages were also viewed with suspicion by the very powerful bureaucratic class, who worried about the influence of the military. This fear had reared its head before: In 1424, between the sixth and seventh voyages, the expedition program was briefly suspended, and Zheng He was temporarily appointed defender of the co-capital Nanjing, where he oversaw construction of the famous Bao’en Pagoda, built with porcelain bricks.

The great admiral died either during, or shortly after, the seventh and last of the historic expeditions, and with the great mariner’s death his fleet was largely dismantled. China’s naval power would recede until the 21st century. With the nation’s current resurgence, it is no surprise that the figure of Zheng He stands once again at the center of China’s maritime ambitions. Today the country’s highly disputed “nine-dash line”— which China claims demarcates its control of the South China Sea—almost exactly maps the route taken six centuries ago by Zheng He and his remarkable fleet.

Related Topics

- IMPERIAL CHINA

The Great Wall of China's long legacy

Why Lunar New Year prompts the world’s largest annual migration

These 5 secret societies changed the world—from behind closed doors

Was Manhattan really sold to the Dutch for just $24?

Go inside China's Forbidden City—domain of the emperor and his court for nearly 500 years

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Coronavirus Coverage

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Corrections

The Seven Voyages of Zheng He: When China Ruled the Seas

In the early 15th century, admiral Zheng He embarked on seven epic voyages, spreading the prestige and influence of Ming China across Southeast Asia, India, Arabia, and even East Africa.

From 1405 to 1433 CE, the Chinese admiral Zheng He led seven great voyages, unmatched in history. The so-called Treasure Fleet traveled to Southeast Asia and India, sailed across the Indian Ocean to Arabia, and even visited the far-flung shores of East Africa.

Zheng He commanded a veritable floating metropolis consisting of 28, 000 men and over 300 vessels, of which 60 were enormous “treasure ships,” nine-masted behemoths over 120 meters (394 foot) long. Sponsored by the Yongle emperor, the Treasure Fleet was designed to spread the influence of Ming China overseas and establish a tributary system of vassal countries. Although the task was successful, bringing over 30 countries under the nominal control of China, political intrigues at the court, and the Mongol threat on the Empire’s northern border, led to the Treasure Fleet’s destruction. As a result, the Ming emperors shifted their priorities inwards, closing China to the world and leaving the high seas to the European navies of the Age of Exploration.

First Voyage of Zheng He and the Treasure Fleet (1405-1407)

On July 11, 1405, after an offering of prayers to the goddess protector of sailors, Tianfei, the Chinese admiral Zheng He and his Treasure Fleet set out for its maiden voyage. The mighty armada comprised of 317 ships, 62 of them being enormous “treasure ships” ( baochuan ), carrying nearly 28,000 men. The fleet’s first stop was Vietnam, a region recently conquered by the Ming dynasty’s armies. From there, the ships proceeded to Siam (present-day Thailand) and the island of Java before reaching Malacca on the southern tip of the Malaysian peninsula. The local ruler quickly submitted to Ming rule , allowing Zheng He to use Malacca as the main base of operations for his armada. It was the beginning of a renaissance for Malacca, which would become a strategically important port for all shipping between India and Southeast Asia in the following decades.

From Malacca, the fleet continued their voyage eastwards, crossing the Indian Ocean and arriving at the main trading ports on the southwest coast of India, including Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) and Calicut. The scene of Zheng He’s 300-vessel armada must have been awe-inspiring to the locals. Unsurprisingly, the local rulers accepted China’s nominal control, exchanged gifts, and their ambassadors boarded the ships, which would take them to China. On their return trip, laden with tribute and envoys, the Treasure Fleet confronted the notorious pirate Chen Zuyi in the Strait of Malacca. Zheng He’s ships destroyed the pirate armada and captured their leader, taking him back to China where he was executed.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription, the second and third voyages: gunboat diplomacy (1407-1409 and 1409-1411).

The defeat of the pirate armada and the destruction of their base at Palembang secured the Malacca strait and the valuable trade routes linking Southeast Asia and India. Everything was ready for the second voyage of Zheng He in 1407. This time a smaller fleet of 68 ships sailed to Calicut to attend the inauguration of the new king. On the return trip, the fleet visited Siam (present-day Thailand) and the island of Java, where Zheng He got embroiled in a power struggle between two rival rulers. Although the Treasure Fleet’s main task was diplomacy, Zheng He’s massive ships carried heavy guns and were filled with soldiers. Therefore, the admiral could get involved in local politics.

After the armada returned to China in 1409 with holds full of tribute gifts and carrying new envoys, Zheng He immediately departed for another two-year voyage. Like the first two, this expedition also terminated at Calicut. Once again, Zheng He employed gunboat diplomacy when he intervened in Ceylon. Ming troops defeated the locals, captured their king, and brought him back to China. Although the Yongle emperor released the rebel and returned him home, the Chinese backed another regime as a punishment.

Fourth Voyage: The Treasure Fleet in Arabia (1413-1415)

Following a two-year pause, in 1413, the Treasure Fleet set out again. This time, Zheng He ventured beyond the ports of India, leading his armada consisting of 63 ships all the way to the Arabian peninsula. The fleet reached Hormuz, a key link between the maritime and overland Silk roads . The smaller fleet visited Aden, Muscat, and even entered the Red Sea. As these were predominantly Muslim lands, it must have been essential for the Chinese to have specialists in Islamic religion onboard.

Once again, Zheng He got entangled in a local conflict, this time in Samudera, on the north coast of Sumatra. The Ming forces, skilled in the art of war , defeated a usurper who had murdered the king and brought him to China for execution. The Ming had focused all their efforts on diplomacy, but when it failed, they secured their own interests by employing the mighty Treasure Fleet against potential troublemakers.

Fifth and Sixth Voyages: The Treasures of Africa (1416-1419 and 1421-1422)

In 1417, the Treasure fleet left China on its longest voyage to date. After it returned various foreign dignitaries to Southeast Asia, Zheng He crossed the Indian Ocean and sailed to the coast of East Africa. The armada visited several major ports, exchanged gifts, and established diplomatic relations with the local leaders. Among the vast quantities of tribute brought back to China were many exotic animals — lions, leopards, ostriches, rhinoceroses, and giraffes — some of them seen by the Chinese for the first time. The giraffe, in particular, was the most peculiar, and the Chinese identified it as a qilin — a legendary beast that in ancient Confucian texts epitomized virtue and prosperity.

However, while the giraffe could be interpreted as an auspicious sign, the Treasure Fleet was costly to maintain and keep afloat. After Zheng He returned from the sixth expedition in 1422, (which also visited Africa) he discovered that his patron and childhood friend — the Yongle emperor — had died on a military campaign against the Mongols. The new Ming ruler was less welcoming to what many courtiers considered expensive far-flung cruises. In addition, the Mongol threat in the north required vast funds to be diverted for military expenditure and the rebuilding and expansion of the Great Wall . Zheng He retained his position at court, but his naval expeditions were halted for several years. The new emperor lived only a few months and was succeeded by his more adventurous son, the Xuande emperor. Under his leadership, Zheng He would make one last grand voyage.

Seventh Voyage of Zheng He: The End of an Era (1431-1433)

Almost ten years after his last voyage, Zheng He was ready for what would became the Treasure Fleet’s final voyage. The great eunuch admiral was 59 years old, in poor health, but was eager to sail again. So, in the winter of 1431, more than a hundred ships and over 27, 000 men left China, sailing across the Indian Ocean and visiting Arabia and East Africa. The primary purpose of the fleet was to return the foreign envoys home, but it also solidified the tributary relationship between Ming China and over thirty overseas countries.

On the return trip in 1433, Zheng He died and was buried at sea. The death of the great admiral and seafarer reflected the fate of his beloved Treasure Fleet. Faced with a continuous Mongol threat from the north and surrounded by powerful Confucian courtiers who had no love for “wasteful adventures” the emperor ended the naval expeditions for good. He also ordered the dismantlement of the Treasure Fleet. With the eunuch faction defeated, the Confucians sought to erase the memory of Zheng He and his voyages from Chinese history. China was opening a new chapter by closing itself to the outside world. In an ultimate act of irony, Europeans began their voyages only a few decades later. Soon, they dominated the high seas, eventually leading to the European arrival in China as the superior power.

The Mongol Empire Versus China: The Way of War

By Vedran Bileta MA in Late Antique, Byzantine, and Early Modern History, BA in History Vedran is a doctoral researcher, based in Budapest. His main interest is Ancient History, in particular the Late Roman period. When not spending time with the military elites of the Late Roman West, he is sharing his passion for history with those willing to listen. In his free time, Vedran is wargaming and discussing Star Trek.

Frequently Read Together

Admiral Zheng He: China’s Forgotten Master of the High Seas

The Mighty Ming Dynasty in 5 Key Developments

What Was the Silk Road & What Was Traded on It?

- Documentary

- Entertainment

- Building Big

- How It’s Made

- Monarchs and Rulers

- Travel & Exploration

The Astonishing Voyages of Zheng He

The monumental voyages of Zheng He redefined the parameters of exploration in the early fifteenth century. Regarded as one of the world’s greatest explorers, admiral Zheng He established Chinese influence around the globe and set a high bar for maritime expeditions for hundreds of years. This is the remarkable story of Zheng He.

Decades before renowned European explorers like Christopher Columbus, Amerigo Vespucci, Bartolomeu Dias, and Pedro Álvares Cabral embarked on their famed voyages during the Age of Discovery, admiral Zheng He had already set out on some of the most daring and extensive maritime expeditions in history.

Between 1405 and 1433, Zheng He led seven epic voyages across the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. These expeditions, involving hundreds of ships and tens of thousands of men, were virtually unparalleled in scale and ambition.

The Zheng He voyages showcased the technological, navigational, and diplomatic achievements of China’s Ming dynasty, and they significantly impacted global trade patterns and cultural exchanges. His journeys laid the groundwork for the interconnected global trade system that developed in the centuries to follow.

The story of Zheng He and the Chinese treasure ship is legendary in China – he is widely celebrated as the most distinguished explorer and adventurer in the annals of Chinese maritime history. This is the remarkable story of the voyages of Zheng He.

The Early Life of Zheng He

A modern wall painting of Zheng He (Credit: Pictures from History / Contributor via Getty Images)

Originally named Ma He, Zheng He was born in 1371 in the southwestern Chinese province of Yunnan. His early life was marked by significant upheaval. At the age of ten, during the Ming Dynasty’s military campaign in Yunnan, he was captured and subsequently entered into imperial service. Despite these early challenges, Zheng He rose through the ranks, demonstrating remarkable intelligence and loyalty. Crucially, he made influential friends while in the service of Zhu Di, who became the Yongle Emperor, the third emperor of the Ming dynasty. It was these connections which eventually led to him becoming one of the most famous maritime explorers in Chinese history.

Zheng He & Yongle

When Zhu Di successfully took the throne and became Emperor Yongle in 1402, Zheng He’s position in the court was set. The emperor, eager to assert Ming China’s power and prestige, initiated a series of ambitious naval expeditions and appointed Zheng He to lead these voyages. This decision marked a significant turning point, transitioning the young man from a court advisor to Admiral Zheng He, the commander of what would become some of history’s most extensive and far-reaching maritime expeditions.

Under Yongle’s patronage, Zheng He led seven grand voyages between 1405 and 1433, reaching far beyond the traditional routes of commerce, developing diplomatic relationships, permanently reshaping Chinese life, and establishing Zheng He as a legendary figure in the annals of exploration.

The Seven Voyages of Zheng He

A giraffe brought to the court of Emperor Yongle (Credit: Pictures from History / Contributor via Getty Images)

Each of the Zheng He voyages was a complex undertaking, involving not just exploration but also diplomatic missions, trade, and the demonstration of Chinese naval might. They were also a way for the emperor to legitimise his position in the international political arena.

These expeditions were unprecedented for their scale and impact. They greatly enhanced the Ming dynasty’s influence across the Indian Ocean and established China as a major maritime power.

Full-sized replica of one of Admiral Zheng He's ships (Credit: ROSLAN RAHMAN / Staff via Getty Images)

There remains some debate as to the size of Zheng He’s ships. The Chinese treasure ship described by Chinese chroniclers was believed to be 127 metres long and 52 metres wide. It is thought it could carry somewhere between 500 and 1,000 people. This would have been double the length of any contemporary wooden ship, and in fact bigger than later ships such as the HMS Victory, launched in the eighteenth century. Indeed it would have therefore been similar in size to nineteenth century iron-hulled steamers.

Yet some scholars doubt the veracity of these claims – written three centuries later – suggesting they were probably no more than 70m in length.

In addition to the famous Chinese treasure ship, the Zheng He voyages also included equine ships carrying horses and repair materials, supply ships carrying food and medical supplies, transport ships, and warships.

The First Voyage: 1405-1407

Believed to have consisted of over 300 ships and almost 28,000 men, the cargo, according to a contemporary writer, included ‘ imperial letters to the countries of the Western Ocean and with gifts to their kings of gold brocade, patterned silks, and coloured silk gauze, according to their status ’. The first of the voyages of Zheng He took him through Southeast Asia, the Horn of Africa and parts of the Arabian Peninsula. It was largely used to establish a Chinese presence, show off the might of their naval power, and to create tributary relationships.

The Second & Third Voyages: 1407/8-1409 and 1409-1411

The second and third voyages of Zheng He were similar in size and purpose to that of the first. The fleet stopped in places like Java and the coastal cities of Siam (modern-day Thailand), India’s Malabar Coast and the Malay Peninsula. They were, like the first voyage, designed to develop and strengthen diplomatic ties, establish new – and expand existing – tributary relationships, and also to deal with disruptions encountered in previous voyages, including one on Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka).

The Fourth Voyage: 1412-1415

The fourth voyage – believed to be the largest of all including close to 29,000 men and over sixty Chinese treasure ships – took Zheng He further than he had been previously. As well as the Malay Peninsula, modern-day Sri Lanka, and Calicut in India, he carried on to the Maldives, Hormuz in the Persian Gulf and, it is believed, the eastern coast of Africa. He traded spices and silks with foreign rulers and returned with diplomatic envoys from a number of countries he visited.

The Fifth Voyage: 1417-1419

One of the primary purposes of the fifth voyage was for Zheng He to return the envoys from whence they came, along with imperial letters and gifts for the various rulers in acknowledgement of them sending representatives to China. The fifth voyage is said to have returned to China with ivory, as well as zebras, camels, ostriches and even giraffes.

The Sixth Voyage: 1421-1422/3

Smaller in size than previous voyages, the sixth voyage was similar in route to the previous trip and visited a number of previous locations. Around two years after Admiral Zheng He returned, the Yongle Emperor died. While Zheng He remained at court, all naval expeditions were suspended and it would be almost a decade before he took his final voyage under the Xuande Emperor.

The Last Voyage of Zheng He

Replica of Zheng He's treasure ship in Nanjing (Credit: China Photos / Stringer via Getty Images)

A huge fleet of Chinese treasure ships set out in 1431 for what would be the last hurrah of Zheng He.

By this time he was around sixty and in failing health, but the lure of the open ocean was too good to refuse. The seventh voyage reached as far west as Hormuz and contemporary sources suggest they visited at least seventeen or even as many as twenty countries. This was to be his final voyage.

There are two competing theories as to the date of the death of Zheng He.

The most commonly accepted theory is that Zheng He died in 1433, either at sea or shortly after his fleet returned to China. This version is widely cited in historical documents and is the one most historians lean towards due to its consistency with the timelines of his voyages and historical records from the Ming dynasty.

A less common but still significant theory suggests that Zheng He died in 1435, two years after the last voyage. This theory is based on some later historical texts and inscriptions that suggest he might have lived beyond the completion of his seventh voyage. However, this theory is not as widely accepted due to less supporting evidence compared to the 1433 theory.

The exact circumstances and location of his death remain uncertain due to the lack of definitive historical records. Despite this, his legacy as a great navigator and diplomat endures, and the voyages of Zheng He continue to be celebrated for their remarkable achievements in maritime history.

The Enduring Legacy of Zheng He

Historic world map (Credit: Photo 12 via Getty Images)

The Zheng He voyages stand as a monumental chapter in the annals of maritime history, showcasing the prowess and ambition of the Ming Dynasty’s naval capabilities.

His journeys surpassed the maritime boundaries of his time, and fostered unprecedented cultural and economic exchanges between China and the rest of the world. The expeditions, marked by their scale, sophistication, and diplomatic finesse, not only redefined global trade routes, but also left an indelible mark on the history of international relations and cross-cultural interactions.

The story of Zheng He continues to inspire and intrigue scholars, and is a reminder of the complexity of the vast, interconnected tapestry of human history.

You May Also Like

Unraveling the secrets of the betz mystery sphere, the legend of aztlan: mythical origin of aztec civilisation, the beast of gevaudan: france’s legendary nightmare, the piltdown man hoax: unravelling a scientific scandal, explore more, adam’s calendar: humanity’s oldest timekeeper, olivier levasseur: the pirate’s code and buried treasure, skyquake: the mysterious sounds from the sky, who started april fools’ day, zosimos of panopolis: alchemy and the quest for knowledge, the mystery of costa rica spheres: ancient artifacts unveiled.

World History Edu

- Famous Explorers

Who was the Chinese Admiral Zheng He?

by World History Edu · February 16, 2024

Zheng He, a Ming Dynasty eunuch admiral, led seven epic voyages from China to Africa, showcasing maritime prowess and diplomatic influence. His expeditions, spanning 1405-1433, established trade routes, promoted cultural exchanges, and demonstrated China’s naval dominance, leaving a lasting legacy on global exploration and intercontinental relations during the early 15th century.

Who were the 10 Most Influential Explorers of the Age of Discovery?

Image: A statue of Zheng He, located at Stadthuys Museum in the Malaysian city of Malacca.

In the article below, World History Edu explores the life and major accomplishments of this famed Chinese explorer:

Zheng He was originally named Ma He. His family were Muslims and had a military background associated with the Mongol Yuan Dynasty.

After the Ming Dynasty overthrew the Mongols, he was captured as a child, taken to the capital Nanjing, and castrated to serve as a eunuch in the imperial court. Despite this early adversity, he proved to be highly capable and intelligent, quickly rising through the ranks.

Rise to Prominence

His prowess and loyalty caught the attention of Zhu Di, the Prince of Yan, who later became the Yongle Emperor. He played a crucial role in Zhu Di’s successful bid for the throne, known as the Jingnan Campaign.

As a reward for his service, Zhu Di, now the Yongle Emperor, entrusted him with a series of naval expeditions that were to make history. It was around this time that Ma He adopted the name Zheng He.

The Seven Voyages

Zheng He’s fleet was a massive armada that included treasure ships reportedly measuring up to 400 feet in length, along with numerous support vessels. These voyages demonstrated the might and wealth of the Ming Dynasty to the rest of the world and established Chinese influence across the Indian Ocean.

- First Voyage (1405-1407): Zheng He’s fleet visited various territories along the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, including Java, Sumatra, and reached as far as the coast of present-day Sri Lanka, establishing Chinese dominance and influence in these regions.

- Subsequent Voyages: Over the next three decades, Zheng He led six more expeditions, extending his routes to the Arabian Peninsula and the East African coast, visiting places such as Malindi (in modern-day Kenya). These voyages facilitated trade, collected tributes from foreign lands, and projected Chinese naval power.

Diplomacy and Trade

Zheng He’s expeditions were not merely displays of naval might but also diplomatic missions. They helped establish and strengthen ties with various nations along the Indian Ocean rim through the Chinese tributary system, where foreign states would acknowledge Ming superiority and in return, receive protection and trade rights.

These missions helped create a maritime trade network that was crucial for the exchange of goods, cultures, and ideas between East and West.

Cultural Exchange

The voyages of Zheng He played a significant role in cultural exchange between China and the visited regions. His fleet carried not just goods, but also technologies, knowledge, and religious beliefs, facilitating a two-way exchange of cultural practices and ideas.

For instance, Zheng He is credited with spreading aspects of Chinese culture, such as Confucianism and Chinese technology, while also bringing back to China knowledge about the wider world.

Zheng He’s voyages were remarkable for their time and left a lasting legacy. They were a testament to the Ming Dynasty’s naval capabilities and its far-reaching influence. However, after Zheng He’s death and the ascension of the Xuande Emperor, China’s policy shifted towards isolationism. The treasure fleets were discontinued, and many of Zheng He’s records and maps were destroyed, marking the end of China’s age of exploration.

Despite this, Zheng He’s legacy lived on in various ways. His voyages demonstrated the potential of international trade and cultural exchange. They also influenced maritime navigation techniques in the Indian Ocean and beyond. In modern times, Zheng He is celebrated as one of China’s greatest explorers, with his life and expeditions being the subject of extensive study and admiration.

Frequently Asked Questions

Zheng He is best known for his seven epic voyages between 1405 and 1433, which took his majestic fleet through the South China Sea, the Indian Ocean, and beyond, reaching as far as the east coast of Africa.

Here are some frequently asked questions about the Chinese admiral and explorer:

When was he born and what was his early life like?

Zheng He, born Ma He in 1371 in what is now Yunnan Province, China, was a Chinese mariner, explorer, diplomat, and fleet admiral during the early Ming Dynasty.

He was captured as a child by Ming forces during their military campaign against the Mongols and was subsequently castrated, becoming a eunuch in the service of the imperial court.

Despite his early hardship, Zheng He rose to prominence in the Chinese imperial court, mainly due to his close relationship with the Yongle Emperor, who ascended the throne in 1402.

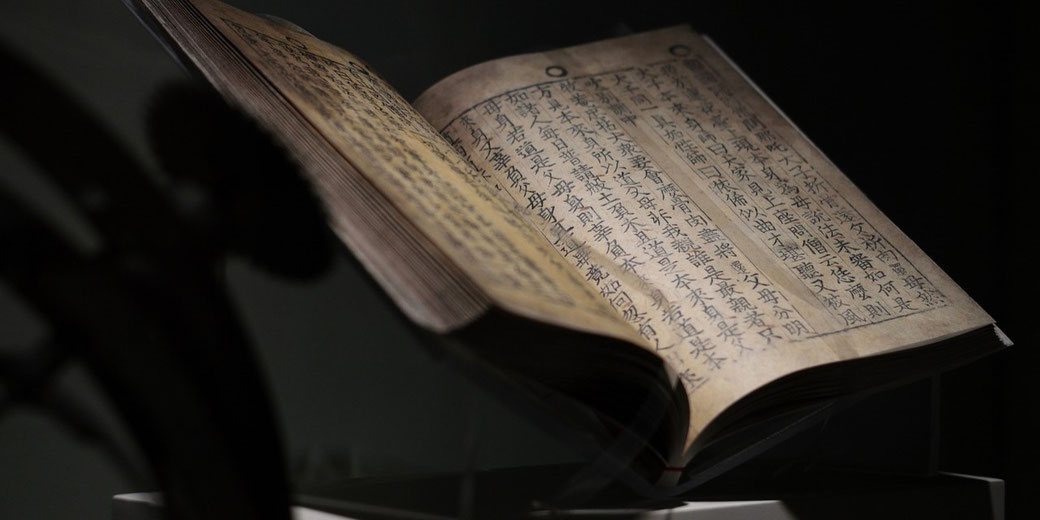

The primary goals of Zheng He’s voyages were to establish Chinese presence, exert imperial control over trade in the Indian Ocean, and extend the tributary system of China. These expeditions were unprecedented in size, scope, and distance, involving hundreds of ships and tens of thousands of sailors.. Image: A woodblock print from China depicting the ships of Zheng He.

What were Zheng He’s voyages about?

Zheng He’s voyages were aimed at establishing Chinese presence and dominance in the Indian Ocean, securing and expanding trade routes, collecting tributes from foreign lands, and promoting diplomatic relations.

How far did Zheng He’s expeditions reach?

Zheng He’s expeditions reached as far as the east coast of Africa, including modern-day Kenya and possibly even beyond.

How many voyages did Zheng He lead?

Zheng He led a total of seven voyages between 1405 and 1433.

How significant were Zheng He’s voyages?

His voyages expanded the horizons of the known world, facilitating trade and cultural exchange on an unprecedented scale. Despite the subsequent period of isolationism that followed his voyages, Zheng He’s legacy as a symbol of China’s historical maritime prowess and its potential for engagement with the world remains influential to this day.

What were Zheng He’s major accomplishments?

His major accomplishments include leading seven grand naval expeditions, establishing and strengthening maritime trade routes, fostering diplomatic relations between China and over 30 countries, and demonstrating the power and wealth of the Ming Dynasty.

How did Zheng He die, and where is he buried?

Zheng He is believed to have died in 1433 during or shortly after his seventh voyage. The exact location of his grave is unknown, but a tomb believed to be symbolic of his burial exists in Nanjing, China.

What happened to Zheng He’s fleet after his voyages?

After Zheng He’s death and the subsequent rise of conservative factions at court, the Ming Dynasty shifted towards isolationism. The great fleets were dismantled, and ocean-going voyages were discouraged.

What were the sizes of Zheng He’s fleets?

Zheng He’s fleets were massive, with some estimates suggesting that the largest voyages consisted of over 250 ships and thousands of crew members, including diplomats and soldiers.

Are there any controversies or debates surrounding Zheng He’s voyages?

Yes, there are debates regarding the purpose and the scale of Zheng He’s voyages, the extent of the territories he might have reached, and the impact of his expeditions on global history, including speculative theories about his fleet reaching the Americas or Australia, which lack historical evidence.

Tags: China Chinese Explorers Ma He Ming Dynasty Yunnan Province Zheng He

You may also like...

Who was Barentsz and how significant was his exploration of the Arctic?

February 9, 2024

Why was Vasco da Gama determined to open trade route to the east?

February 3, 2024

John Cabot: History and Major Accomplishment of the Renowned Italian Explorer

February 6, 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Next story Religious Practices and Major Deities of Pre-Columbian Civilizations

- Previous story What were the Pre-Columbian Civilizations in America?

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

Life and Major Works of Giuseppe Bazzani (23 September 1690 – 17 August 1769), the Italian painter of Late Baroque

Most Famous Admirals of All Time

Hraesvelgr in Norse Mythology: Origin Story & Depiction

Hayreddin Barbarossa: History & Accomplishments

Life and Major Accomplishments of General Douglas MacArthur

Greatest African Leaders of all Time

Queen Elizabeth II: 10 Major Achievements

Donald Trump’s Educational Background

Donald Trump: 10 Most Significant Achievements

8 Most Important Achievements of John F. Kennedy

Odin in Norse Mythology: Origin Story, Meaning and Symbols

Ragnar Lothbrok – History, Facts & Legendary Achievements

9 Great Achievements of Queen Victoria

12 Most Influential Presidents of the United States

Most Ruthless African Dictators of All Time

Kwame Nkrumah: History, Major Facts & 10 Memorable Achievements

Greek God Hermes: Myths, Powers and Early Portrayals

8 Major Achievements of Rosa Parks

10 Most Famous Pharaohs of Egypt

How did Captain James Cook die?

Kamala Harris: 10 Major Achievements

Poseidon: Myths and Facts about the Greek God of the Sea

How and when was Morse Code Invented?

Nile River: Location, Importance & Major Facts

The Exact Relationship between Elizabeth II and Elizabeth I

- Adolf Hitler Alexander the Great American Civil War Ancient Egyptian gods Ancient Egyptian religion Apollo Athena Athens Black history Carthage China Civil Rights Movement Cold War Constantine the Great Constantinople Egypt England France Germany Hera Horus India Isis John Adams Julius Caesar Loki Military Generals Military History Nobel Peace Prize Odin Osiris Pan-Africanism Queen Elizabeth I Ra Religion Set (Seth) Soviet Union Thor Timeline Turkey West Africa Women’s History World War I World War II Zeus

Zheng He (1371–1433): China’s masterful mariner and diplomat

(A fairy tale?)

Ever since Gavin Menzies, a British retired naval officer, published the fictional story 1421: The Year China Discovered America , fleet admiral and diplomat Zheng He (1371–1433) has enjoyed a sort of revival as the Chinese explorer who might have circumnavigated the Earth before the age of Western exploration. I don’t know whether this is true or not, so let’s skip this take on him.

This trope replaces the previous one that had cast Zheng He as the luckless admiral who might have led China in an effort to establish an overseas empire , were it not for the inward looking Confucian bureaucrats in Nanjing and Beijing, who closed China to the world.

In fairness to history, the third Ming emperor, Yongle (1402–1424), who selected Zheng He to be the commander in chief of what became a series of missions to the ‘Western Oceans’, was a man of action. He overextended the empire’s resources , and at the end of his reign, retrenchment became inevitable in face of the collapse of the paper-money system which had funded his many adventures, and those of Zheng He. The abandonment of the Indian Ocean reflects a more realistic view of China’s possibilities. Still, completing the Great Wall of China (which the Chinese actually called The Long Wall) is taken to be a symbol of the Ming dynasty’s inward looking attitude.

Trade monopoly: Europe vs China

Could China have profited from an overseas empire? We in the West see empire-building as such a self-evident policy that we don’t stop a minute and reflect on the fact that China and Europe were different. The first was a unified empire , the second a region of warring statelets .

1. If one is an European warring state keen on profit from international trade, the thing to do is to obtain an import monopoly in Europe , and the rest of Europe will have to pay the import prices set by the monopolist (revenues may be then invested (or wasted) in intra-European warring). To protect the monopoly position within Europe, one needs to protect the supply chain all the way up to the overseas producer. This is why the Dutch settled in Indonesia, and the British in Bengal. Competitive empire-building reflects the fragmented structure of warring Europe.

China on the other hand was a unified state. It was immaterial where the imports landed. In fact, an open trading system ensured China competitive prices. From all over the Indian Ocean and the Indonesian archipelago, traders, both foreign and Chinese, brought goods to China unbidden . Canton (Guangzhou) was a majority Muslim, reflecting their prominent role in the Indian Ocean. On the other hand, Chinese communities have taken on predominant roles along the coast of Indonesia.

2. Europe needed goods from the Orient. While China certainly appreciated goods from Indian Ocean trading, it needed foremost horses for its troops . That explains in part the fixation with the nomads to the north: it had a vital interest there and was ready to pay for it in silk. The Silk Road at the outset was a way for the nomadic Xiongnu to get rid, in India and the West, of surplus silk they’d gotten from the Han in exchange for horses under the tribute system. Its political roots lie in the realisation that neither side could win at war, and thus unilateral rent extraction through conquest respective pillage was not a viable policy.

Ever since the Song Empire (960–1279), China maintained a political presence in Southeast Asia, and a few political missions on squadrons had been sent into the region. Ming Emperor Yongle’s effort to send a fleet under Zheng He into the Indian Ocean has to be understood as a reinforcement and continuation of this policy. But was it necessary?

Zheng He’s fleet and voyages

Zheng He’s fleet of 250 ships, with 27,000 sailors and soldiers on board, sailed 7 times altogether into the Indian Ocean, visiting in turn Indonesia, Ceylon, Calicut, Hormuz, Aden, and Africa, all the way down to Malindi in present-day Kenya. It was an effort ‘to bring the Western Ocean into the Chinese tributary system by overawing, or if need be overpowering, opposition’ (from Edward L. Dreyer’s book Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433 ). So they did, fighting in Ceylon, capturing pirates in Indonesia, and unseating a local pretender there. For the rest, they brought home goods – like the mythical qilin (giraffe) – and other ‘goods and treasures without name, which were too many to be accounted for, yet they did not make up for the wasteful expenses’, sneered the Confucian bureaucrats.

China and trade

And they were right, in a way: the terms of trade for horses were set at China’s northern door and the nomads paid the associated transport costs. Here, the exchange took place at the port of call, far away from China. The terms of trade reflected local conditions, and on top of that, China had to pay for transport costs. In economic terms, there was no way China could win. The Indian Ocean trading system brought goods to China – unbidden. A policy of dominance could increase the flow (at the risk of creating a supply overhang), but only by shouldering the collateral costs. And as a final point: silk textiles were being produced in India and the Middle East; what was in demand from China by then was tea and porcelain . Zheng He, as a good bureaucrat, may have missed the prevailing market conditions.

China’s tribute system

Most profoundly, China’s tribute system reflected a strategic choice: it represented a system of peaceful and commercial exchange in dealing with foreign powers – eschewing rent extraction through force. Given this choice, for all its ritual complexity, the tribute system was no more than a system of public procurement for vital goods (army horses from nomads in the north). There were no vital goods the Chinese state (or the Chinese court) saw the necessity to procure in the Indian Ocean. 1 Consequently it applied a policy of benign (or malign 2 at times) neglect.

How much did Zheng He’s explorations cost?

How much did all this cost? Building the fleet absorbed about half the tax receipts for one year, and then there was the expense of running the operation. A doable policy, but not a marginal expense, and therefore it was subjected to scrutiny as to its effectiveness. Showing the flag impressed everyone in sight, but politically they were all dwarfs. These places were duly impressed, went about the required motions of showing respect, and then settled back into their well-established routines as trade nodes. Even Calicut, or Hormuz, were just platforms of exchange, not of large scale production. In this light, retrenchment is understandable.

A unique, self-sufficient fleet

What about Zheng He? Zheng He was a genius in his own way, albeit unrecognised to this day. His skill was in the area of logistics and organisation, and here he still is unmatched.

To my knowledge, there has never been (nor is there today) a fleet able to ‘project power’ (an army of over 5,000 marines at the ready) in foreign waters repeatedly, for a period of up to 2 years each time (with a turn-around time of 4–6 months between missions). Along the way, the fleet was essentially self-sufficient, both as to supplies and to the upkeep of the ships. These were flat-bottomed wooden vessels with capital ships weighing around 20,000T each (opinions differ somewhat on this point), 4 times the largest ships of the Western line, lumbering at 2–3 knots of speed powered by 9 masts, and able to sail for 20–30 days out of sight of land. And though he may have lost the odd vessel, in the 30 years that the fleet was kept up, Zheng He never lost even a fraction of the fleet to storm.

What an engineering and organisational performance!

1. When Emperor Qianlong, who reigned 1735–1796, indicated to the British Envoy Macartney in 1793 that China did not need any British goods, he was using such a ‘public (or court) procurement’ lens. From such an angle, the statement was understandable.

2. Trade between China and Southeast Asia continued, disrupted at times by imperial edicts, and then followed by accommodation.

This post was first published on DeepDip.

Browse through our Diplo Wisdom Circle (DWC) blog posts .

Related blogs

Related events, related resources, related histories, leave a reply, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Subscribe to Diplo's Blog

Diplo: effective and inclusive diplomacy.

Diplo is a non-profit foundation established by the governments of Malta and Switzerland. Diplo works to increase the role of small and developing states, and to improve global governance and international policy development.

Diplo on Social

Want to stay up to date.

Subscribe to more Diplo and Geneva Internet Platform newsletters!

Zhen He's Voyages to the West

Zheng He (or Ma Sanbao) (1371-1433 AD) was a court eunuch, marine explorer and fleet admiral, born into an adventurous Muslim family in Kunyang of Yunnan Province. His grandfather was a noble from the Mongolian tribe and once made a pilgrimage to Mecca. Ma Sanbao had an elder brother and two sisters. His parental family was greatly respected in Kunyang for its pious religious beliefs.

The Ming Army attacked Yunnan in 1381, and the eleven-year old Ma Sanbao was captured, castrated and brought to the palace of the Prince of Yan (later the Yongle Emperor) to serve as a eunuch.

In the battle of Zhengzhou (presently Renqiu of Hebei Province), Ma helped the Prince of Yan, Zhu Di, to seize the throne of Emperor Jianwen. As a reward after ascending the throne, Zhu Di bestowed the imperial surname "Zheng" on Ma Sanbao; hence the name Zheng He.

Between 1405 and 1433 , under Emperor's orders, Zheng He led seven expeditionary ocean voyages to western countries . This was a great feat in the history of Chinese marine navigation, in recognition of which the title Sanbao Eunuch (Three-Protection Eunuch) was conferred on Zheng in 1431.

Preconditions of Zheng He's Marine Voyages

- The shipbuilding industry prospered during the Tang (618–907 AD) and Song (960–1279 AD) dynasties, making long-distance oceanic exploration possible.

- The development of compasses and gunpowder provided reassurance for oceanic exploration, in regard to security.

- The Yongle Emperor was showing off marine prowess for political reasons.

- Ocean trade prospered during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368 AD). The Yuan Empire boasted the strongest army and largest fleet in the world, laying a good foundation economically and militarily for marine exploration.

- Sailors, soldiers and translators worked together to accomplish the task of exploration.

Zheng He's Seven Voyages to the West

Zheng He left on his 1st voyage in 1405 with a fleet of 240 ships and visited over 30 states along the coasts of the West Atlantic and Indian Oceans. His visits helped to strengthen relations between China and countries in Southeast Asia and East Africa. Zheng's 7th voyage was cut short in 1433 owing to his death at Guli in India. He and his crewmen had traveled as far as the Red Sea and the East African coast.

The First Voyage

On June 15th, 1405, Zheng He set sail from Longjiang Harbor in Nanjing , and returned on September 2nd, 1407. According to records, more than 27,800 crewmen participated in the voyage. During this first voyage, Zheng visited Champa (presently Vietnam), Java Island, Malacca, Aru, Samudera, Qiulon, Kollam, Cochin (presently South West India) and Calicut (presently South India).

The Second Voyage

On September 13th, 1407, only 11 days after his return from the first voyage, Zheng left with his fleet for a second time. During this trip he visited Champa, Java Island, Siam (presently Thailand), Malacca, Cochin, Ceylon (presently Sri Lanka) and Calicut.

In July 1409, on his return voyage, Zheng made a special trip to Ceylon and erected a monument at Mt. Ceylon Temple to commemorate the voyage. It was estimated that over 27,000 crewmen had joined in the voyage.

The Third Voyage

In September 1409, Zheng left with a fleet of 48 ships from Liujiagang, Suzhou in Jiangsu Province, on a third voyage to the West. This time he visited Champa, Java, Malacca, Semudera, Ceylon, Quilon, Cochin, Calicut, Siam, Lambri and Kayal (namely, present-day Vietnam), Indonesia, Malaysia and India. On July 9th, 1411, Zheng was presented with relics from the Buddha via Ceylon, while on his way home.

The Fourth Voyage

Over 27,670 crewmen were enrolled on Zheng He's fourth journey to the West, which departed in November 1413. They made a detour round the Arabian Peninsula and sailed as far as Mogadishu and Malindi (presently in Kenya). On July 8th, 1415, Zheng and his fleet returned home. At that time, an envoy from Malindi presented giraffes to the Ming emperor.

The Fifth Voyage

Zheng's fifth voyage to the West started at Quanzhou (presently in Guangdong Province) in May 1417 and ended at Ma Lam (an ancient kingdom in an East African country) via Champa and Java Island. Zheng sailed home on July 17th, 1419. On his return, the Aden Kingdom presented unicorns, Maldive lions and Barawa ostriches to the Ming emperor.

The Sixth Voyage

On September 30th, 1421, Zheng left China with a fleet of ships to escort foreign envoys home. He passed through Champa, Bengal, Ceylon, Calicut, Cochin, Maldives, Hormuz, Djofar, Aden, Mogadishu and Brava. The fleet returned home on August 18th, 1422, with more envoys from Siam, Samudera and Aden.

In the 22nd year of the Yongle period (1426), the Yongle Emperor passed away, and Zhu Gaozhi (later known as the Renzong Emperor) ascended the throne. Zhu stopped Zheng's voyages to the West, owing to bankruptcy.

The Seventh Voyage

On December 6th, 1431, Zheng He set sail towards the West for a 7th time, from Longjiangguan (presently Xiaguan in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province). He died from overwork in 1433, on the homeward voyage. The fleet was then led by another eunuch, Wang Jinghong, and returned to Nanjing on July 7th, 1433. The number of crewmen on that voyage was 27,550.

Zheng He's Contribution to Global Ocean Exploration

Zheng He's travels to the West were unprecedented in their scale and scope. Zheng made a great contribution to friendly relations between China and the rest of the world in the spheres of politics, economy and culture.

Zheng's travels to the West turned a new page in the history of world marine navigation, 87 years before Christopher Columbus discovered America, 92 years before Vasco da Gama discovered the Cape of Good Hope and 114 years before Magellan sailed around the globe.

In China, Zheng He is regarded as an outstanding diplomat and navigator. His travels to the West made a great impact on world history, for which he is justifiably renowned.

- 11-Day China Classic Tour

- 3-Week Must-See Places China Tour Including Holy Tibet

- 8-Day Beijing–Xi'an–Shanghai Private Tour

- How to Plan Your First Trip to China 2024/2025 — 7 Easy Steps

- 15 Best Places to Visit in China (2024)

- Best (& Worst) Times to Visit China, Travel Tips (2024/2025)

- How to Plan a 10-Day Itinerary in China (Best 5 Options)

- China Weather in January 2024: Enjoy Less-Crowded Traveling

- China Weather in March 2024: Destinations, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in April 2024: Where to Go (Smart Pre-Season Pick)

- China Weather in May 2024: Where to Go, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in June 2024: How to Benefit from the Rainy Season

- China Weather in July 2024: How to Avoid Heat and Crowds

- China Weather in August 2024: Weather Tips & Where to Go

- China Weather in September 2024: Weather Tips & Where to Go

- China Weather in October 2024: Where to Go, Crowds, and Costs

- China Weather in November 2024: Places to Go & Crowds

- China Weather in December 2024: Places to Go and Crowds

Get Inspired with Some Popular Itineraries

More travel ideas and inspiration, sign up to our newsletter.

Be the first to receive exciting updates, exclusive promotions, and valuable travel tips from our team of experts.

Why China Highlights

Where can we take you today.

- Southeast Asia

- Japan, South Korea

- India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Sri lanka

- Central Asia

- Middle East

- African Safari

- Travel Agents

- Loyalty & Referral Program

- Privacy Policy

Address: Building 6, Chuangyi Business Park, 70 Qilidian Road, Guilin, Guangxi, 541004, China

Biography of Zheng He, Chinese Admiral

hassan saeed / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0

- Figures & Events

- Southeast Asia

- Middle East

- Central Asia

- Asian Wars and Battles

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- Ph.D., History, Boston University

- J.D., University of Washington School of Law

- B.A., History, Western Washington University

Zheng He (1371–1433 or 1435) was a Chinese admiral and explorer who led several voyages around the Indian Ocean. Scholars have often wondered how history might have been different if the first Portuguese explorers to round the tip of Africa and move into the Indian Ocean had met up with the admiral's huge Chinese fleet . Today, Zheng He is considered something of a folk hero, with temples in his honor throughout Southeast Asia.

Fast Facts: Zheng He

- Known For : Zheng He was a powerful Chinese admiral who led several expeditions around the Indian Ocean.

- Also Known As : Ma He

- Born : 1371 in Jinning, China

- Died : 1433 or 1435

Zheng He was born in 1371 in the city now called Jinning in Yunnan Province. His given name was "Ma He," indicative of his family's Hui Muslim origins since "Ma" is the Chinese version of "Mohammad." Zheng He's great-great-great-grandfather Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar was a Persian governor of the province under the Mongolian Emperor Kublai Khan , founder of the Yuan Dynasty that ruled China from 1279 to 1368.

Ma He's father and grandfather were both known as "Hajji," the honorific title bestowed upon Muslim men who make the "hajj," or pilgrimage, to Mecca. Ma He's father remained loyal to the Yuan Dynasty even as the rebel forces of what would become the Ming Dynasty conquered larger and larger swathes of China.

In 1381, the Ming army killed Ma He's father and captured the boy. At just 10 years old, he was made into a eunuch and sent to Beiping (now Beijing) to serve in the household of 21-year-old Zhu Di, the Prince of Yan who later became the Yongle Emperor .

Ma He grew to be seven Chinese feet tall (probably around 6-foot-6), with "a voice as loud as a huge bell." He excelled at fighting and military tactics, studied the works of Confucius and Mencius, and soon became one of the prince's closest confidants. In the 1390s, the Prince of Yan launched a series of attacks against the resurgent Mongols, were based just north of his fiefdom.

Zheng He's Patron Takes the Throne

The first emperor of the Ming Dynasty , Prince Zhu Di's eldest brother, died in 1398 after naming his grandson Zhu Yunwen as his successor. Zhu Di did not take kindly to his nephew's elevation to the throne and led an army against him in 1399. Ma He was one of his commanding officers.

By 1402, Zhu Di had captured the Ming capital at Nanjing and defeated his nephew's forces. He had himself crowned as the Yongle Emperor. Zhu Yunwen probably died in his burning palace, although rumors persisted that he had escaped and become a Buddhist monk. Due to Ma He's key role in the coup, the new emperor awarded him a mansion in Nanjing as well as the honorific name "Zheng He."

The new Yongle Emperor faced serious legitimacy problems due to his seizure of the throne and the possible murder of his nephew. According to Confucian tradition, the first son and his descendants should always inherit, but the Yongle Emperor was the fourth son. Therefore, the court's Confucian scholars refused to support him and he came to rely almost entirely upon his corps of eunuchs, Zheng He most of all.

The Treasure Fleet Sets Sail

Zheng He's most important role in his master's service was being the commander-in-chief of the new treasure fleet, which would serve as the emperor's principal envoy to the peoples of the Indian Ocean basin. The Yongle Emperor appointed him to head the massive fleet of 317 junks crewed by over 27,000 men that set out from Nanjing in the fall of 1405. At the age of 35, Zheng He had achieved the highest rank ever for a eunuch in Chinese history.

With a mandate to collect tribute and establish ties with rulers all around the Indian Ocean, Zheng He and his armada set forth for Calicut on India's western coast. It would be the first of seven total voyages of the treasure fleet, all commanded by Zheng He, between 1405 and 1432.

During his career as a naval commander, Zheng He negotiated trade pacts, fought pirates, installed puppet kings, and brought back tribute for the Yongle Emperor in the form of jewels, medicines, and exotic animals. He and his crew traveled and traded not only with the city-states of what are now Indonesia, Malaysia , Siam , and India , but also with the Arabian ports of modern-day Yemen and Saudi Arabia .

Although Zheng He was raised Muslim and visited the shrines of Islamic holy men in Fujian Province and elsewhere, he also venerated Tianfei, the Celestial Consort and protector of sailors. Tianfei had been a mortal woman living in the 900s who achieved enlightenment as a teenager. Gifted with foresight, she was able to warn her brother of an approaching storm at sea, saving his life.

Final Voyages

In 1424, the Yongle Emperor passed away. Zheng He had made six voyages in his name and brought back countless emissaries from foreign lands to bow before him, but the cost of these excursions weighed heavily on the Chinese treasury. In addition, the Mongols and other nomadic peoples were a constant military threat along China's northern and western borders.

The Yongle Emperor's cautious and scholarly elder son, Zhu Gaozhi, became the Hongxi Emperor. During his nine-month rule, Zhu Gaozhi ordered an end to all treasure fleet construction and repairs. A Confucianist, he believed that the voyages drained too much money from the country. He preferred to spend on fending off the Mongols and feeding people in famine-ravaged provinces instead.

When the Hongxi Emperor died less than a year into his reign in 1426, his 26-year-old son became the Xuande Emperor. A happy medium between his proud, mercurial grandfather and his cautious, scholarly father, the Xuande Emperor decided to send Zheng He and the treasure fleet out again.

In 1432, the 61-year-old Zheng He set out with his largest fleet ever for one final trip around the Indian Ocean, sailing all the way to Malindi on Kenya's east coast and stopping at trading ports along the way. On the return voyage, as the fleet sailed east from Calicut, Zheng He died. He was buried at sea, although legend says that the crew returned a braid of his hair and his shoes to Nanjing for burial.

Although Zheng He looms as a larger-than-life figure in modern eyes both in China and abroad, Confucian scholars made serious attempts to expunge the memory of the great eunuch admiral and his voyages from history in the decades following his death. They feared a return to the wasteful spending on such expeditions. In 1477, for example, a court eunuch requested the records of Zheng He's voyages with the intention of restarting the program, but the scholar in charge of the records told him that the documents had been lost.

Zheng He's story survived, however, in the accounts of crew members including Fei Xin, Gong Zhen, and Ma Huan, who went on several of the later voyages. The treasure fleet also left stone markers at the places they visited.

Today, whether people view Zheng He as an emblem of Chinese diplomacy and "soft power" or as a symbol of the country's aggressive overseas expansion, all agree that the admiral and his fleet stand among the great wonders of the ancient world.

- Mote, Frederick W. "Imperial China 900-1800." Harvard University Press, 2003.

- Yamashita, Michael S., and Gianni Guadalupi. "Zheng He: Tracing the Epic Voyages of China's Greatest Explorer." White Star Publishers, 2006.

- Timeline: Zheng He and the Treasure Fleet

- Biography of Zhu Di, China's Yongle Emperor

- The Seven Voyages of the Treasure Fleet

- Why Did Ming China Stop Sending out the Treasure Fleet?

- Biography of Explorer Cheng Ho

- Emperors of the Ming Dynasty

- Zheng He's Treasure Ships

- What Is a Qilin?

- Indian Ocean Trade Routes

- Han Dynasty's Emperors of China

- China's Forbidden City

- History of the Pekingese Dog

- Country Profile: Malaysia Facts and History

- Puyi, China's Last Emperor

- Biography of Qin Shi Huang, First Emperor of China

- Was Sinbad the Sailor Real?

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center