STORY ENVELOPE

Storytelling

The story circle in 8 steps with tons of examples.

May 9, 2023

Now Trending:

I'm COLETTE NICHOL

I'm a solo filmmaker , story strategist, SEO consultant , and educator. I'm here to either help you grow your business or start making films! Can't wait to meetcha! While you're here, make sure you sign up for the filmmaking newsletter. Or grab the free SEO Checklist for Beginners.

Free Quiz: Discover Your Filmmaker Archetype

Plus find out the exact GEAR you need to get started. Plus get tips on next steps you can take to advance your career.

27 Tips to Get Your Website More Traffic

Get my SEO Checklist for Beginners. This starter checklist will give you an overview of what it takes to drive more traffic to your site.

Dan Harmon’s Story Circle Is a Modern Take on the Hero’s Journey

Article by Colette Nichol, Story Strategist, SEO Expert, and Solo Filmmaker

What Is Dan Harmon’s Story Circle with Examples?

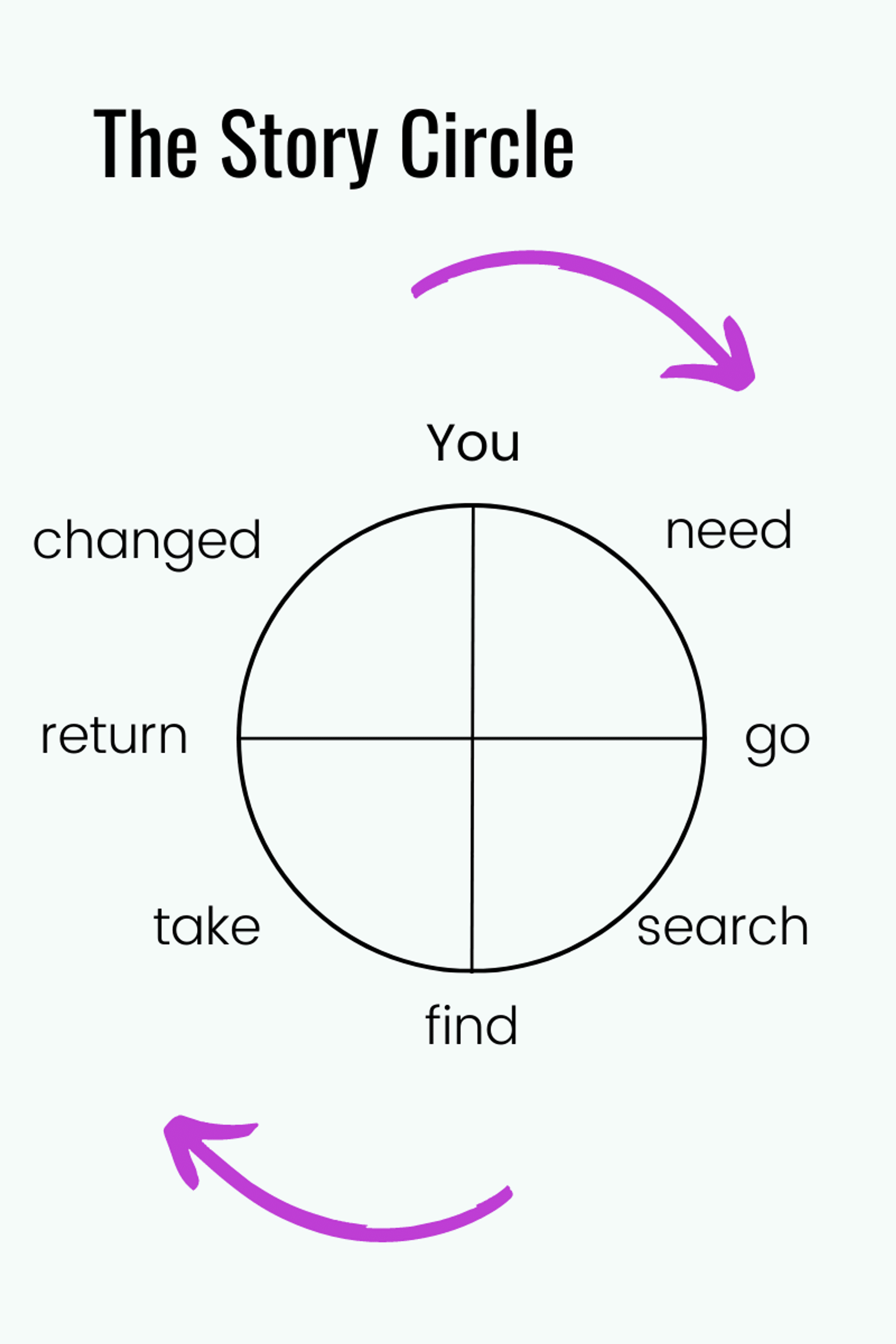

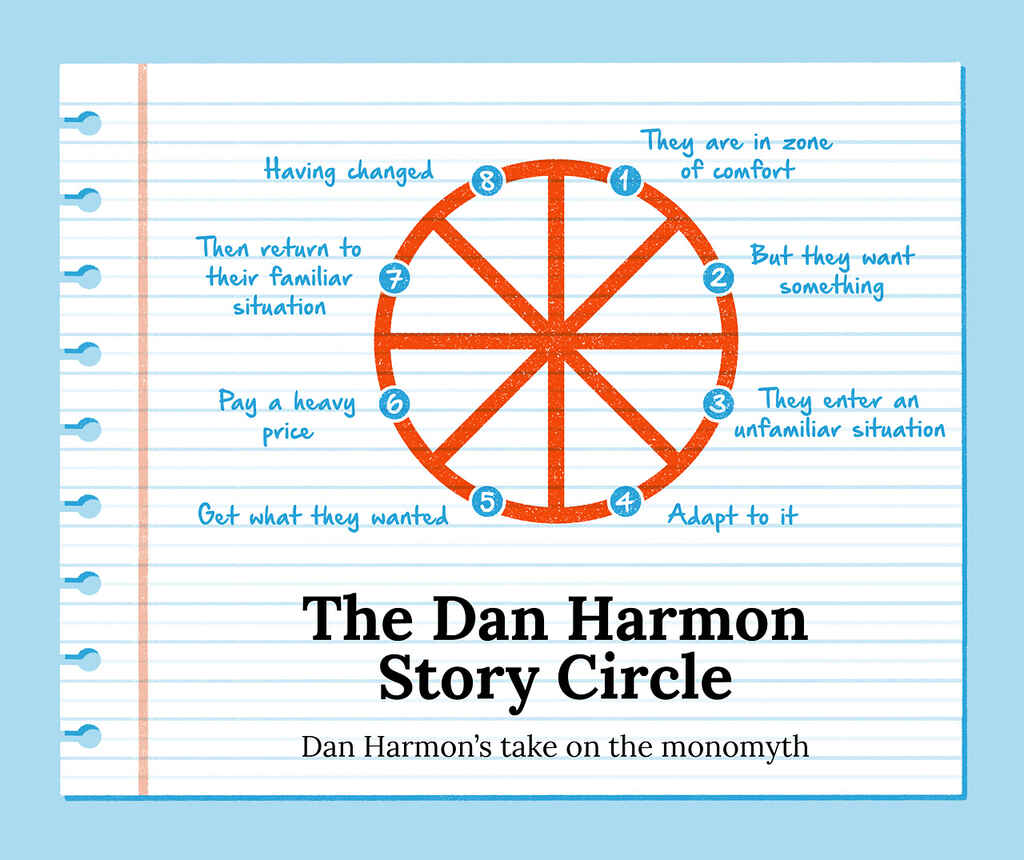

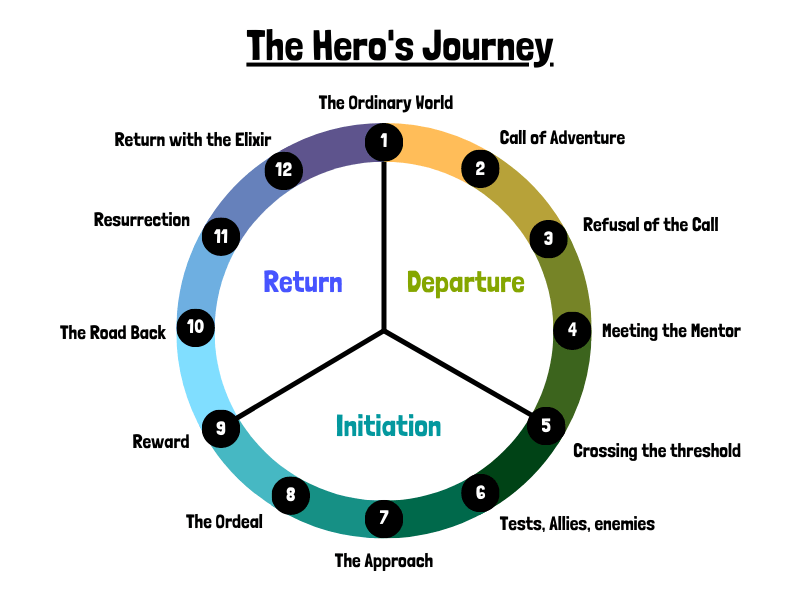

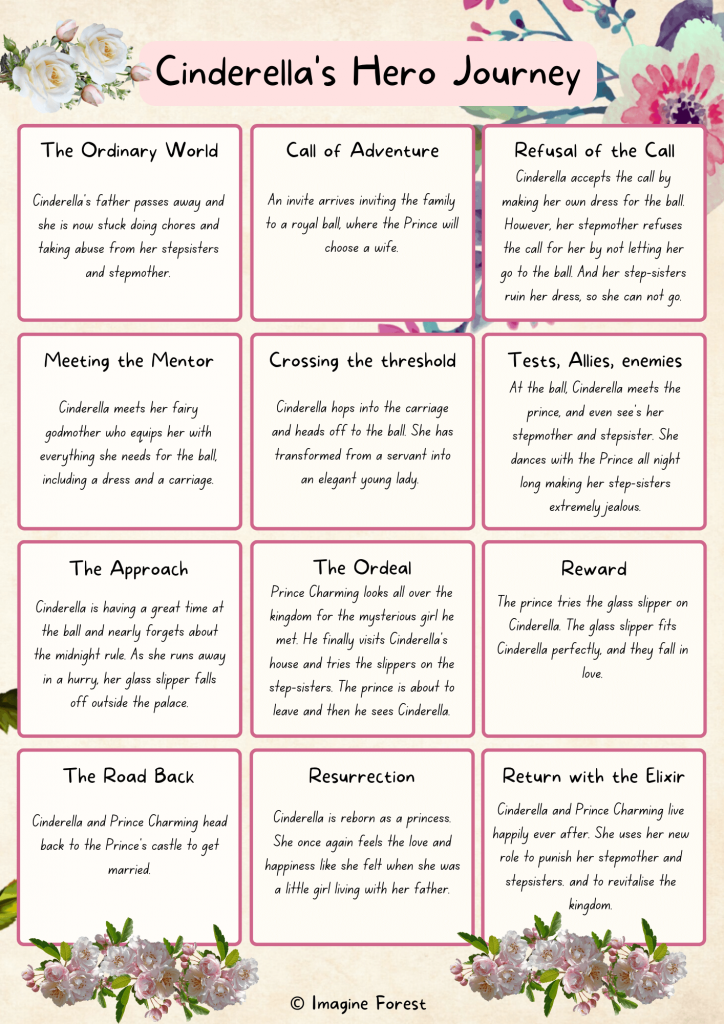

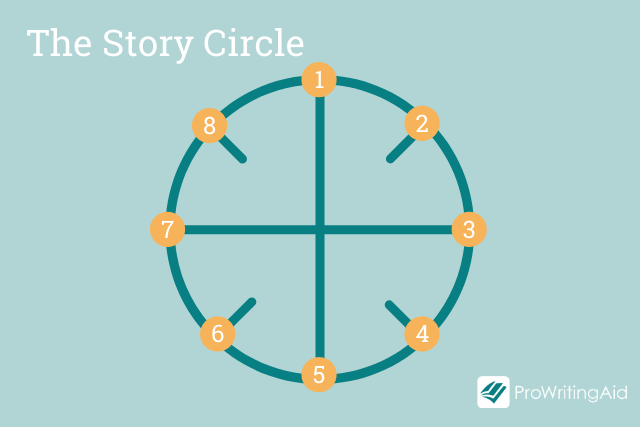

The story circle is a story structure guide created by Dan Harmon based on Joseph Campbell’s analysis of the Hero’s Journey.

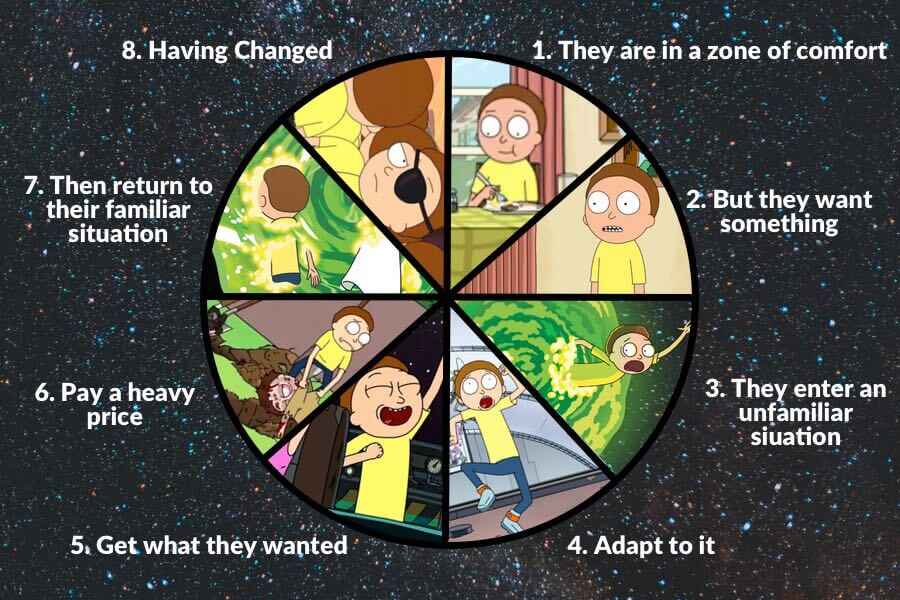

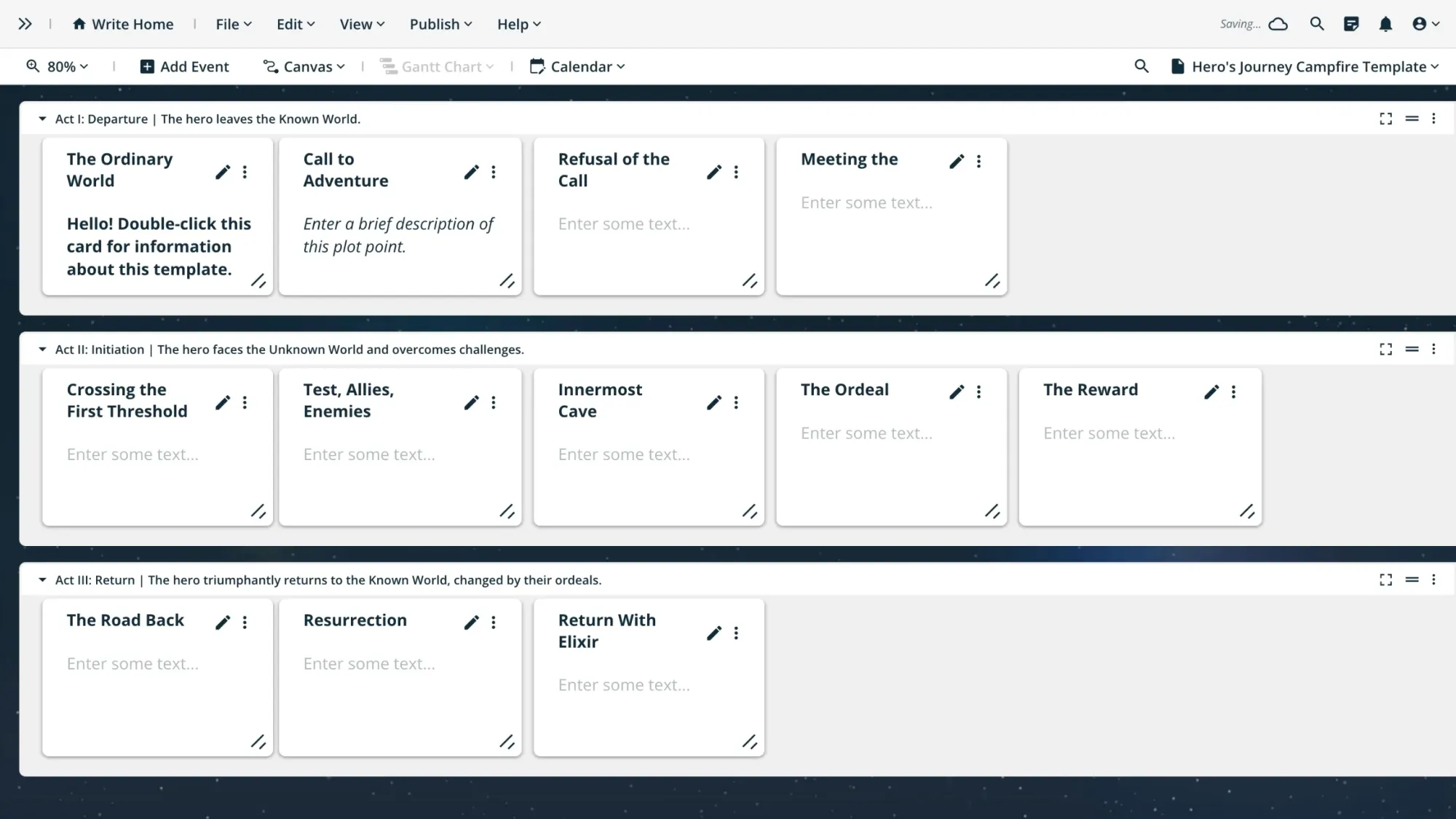

The story circle consists of the eight main plot points that create a story’s foundational structure, which Dan Harmon has labelled: you, need, go, search, find, take, return, changed.

- You – A character with a problem.

- Need – Has a need.

- Go – And crosses the threshold in the world of adventure.

- Search – To find the answer to their problem.

- Find – They find that things are not what they seem.

- Take – They get what they want but it was not as they expected.

- Return – They return to the ordinary world.

- Changed – And they are transformed by their journey.

For a ton of extensive examples with videos, read through this entire post where I cover each important turning point in a story in details with examples. But first, some background!

Who Is Dan Harmon?

Dan Harmon is a TV writer known for writing and creating Community.

He also co-created Rick and Morty and is credited with writing 61 episodes.

To get the juices flowing in the writer’s room and guide the writing of new episodes, he simplified the hero’s journey into eight key concepts that make it easy to assess or build a story idea quickly.

It’s brilliant. It’s simple. And dammit, it’s delicious!

I got obsessed with Dan Harmon’s story circle a few years ago, hunting down every time Harmon wrote about or spoke about his method of breaking down stories. If he talked about it on the internet, I found it and ate it up.

It’s not that Harmon is saying anything new.

But the way he’s broken down the Hero’s Journey is so practical and, frankly, beautiful that it’s worth knowing and using. If you’re a writer, storyteller, director, producer, or even business owner, you need to know how to pull apart and put together a story.

So let’s discuss and dissect this beautiful tool. Onward!

Table of Contents

- How Dan Harmon’s Story Circle Works

- Part 1: The 8 Stages of Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

YOU, NEED: A Protagonist Needs Something

Go: the hero crosses the threshold into the world of adventure, search: the hero is on the road of trials, find: reckonings, meeting the goddess, vulnerability, bliss, take: the face off, meet your maker, facing the father, return: the flight home, change: the hero is transformed and shares their wisdom, the universal structure of storytelling, top and bottom half of the story circle, part 2: the world of adventure vs. the regular world, crossing the threshold, part 3: starting value or idea and ending value or idea, watch: the dan harmon story circle explained by dan harmon.

- Common Story Circle Questions

How Dan Harmon’s Story Circle Works

First, let me be clear that I’m explaining the story circle in the way that I use it.

I’m not Dan Harmon, and I’m not trying to explain this concept verbatim. So take what you want from this analysis, and don’t hold it against me if I don’t explain this exactly the way Dan Harmon does.

That said, I’m probably the only person on the internet who has hunted down every single thing Mr. Harmon has written about the story circle, put it in a Google doc, printed it, highlighted it, and then practiced it…over and over again!

Anyway, at the end of the day, what matters is HOW you use this information, not whether it was delivered to you in some perfect authoritative package. Now, let’s get to it!

There are three main parts to the story circle:

- The 8 Stages

- The World of Adventure vs. The Regular World

- The Starting Value/Idea vs. The Ending Value/Idea

Part 1: The 8 Stages of Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

There are eight basic stages in the structure of Dan Harmon’s story circle.

It’s no different from the eight stages in the Hero’s Journey. But the way he describes these stages, with a punchy one-word descriptor, makes this tool easy to use.

- Stage 1: YOU

- Stage 2: NEED

- Stage 3: GO

- Stage 4: SEARCH

- Stage 5: FIND

- Stage 6: TAKE

- Stage 7: RETURN

- Stage 8: CHANGE

Before I describe how to interpret and use these stages, look at that list yourself. What do you think each stage means?

Think of a story in your life, and run it through those stages.

You: The Main Character Is in the Comfort Zone

Before anything crazy happens, it’s just you and your regular everyday life.

Things aren’t great. You’re dissatisfied. But you’re not willing to make massive changes. You’re just living life in a quasi-apathetic state, aka normal.

Every story needs a hero—ideally, one, not ten. Even multi-character dramas or action movies like Oceans 11 have one main character who drives the story forward.

Need: The Character Wants Something, Desire Blooms

You want something. You’re not satisfied with just the status quo. Either this desire comes internally and is there before the inciting incident. Or something or someone comes along and awakens the desire within you.

Story Circle Examples

Wizard of oz story structure example:.

Dorothy is in the black-and-white world, moaning and groaning (in song) about how she’d like to be somewhere over the rainbow rather than hanging in Kansas. She needs something to happen so she can escape from her humdrum lands.

Beauty and the Beast Story Structure Example:

Belle reads her fantasy adventure book and longs to be in the middle of a great adventure.

STAGE 1 & 2 – STORY CIRCLE MOVIE EXAMPLE

Go: The Hero Takes Action, Crosses the Threshold and Enters an Unfamiliar World

Your bags are packed, and you’re not just ready to go; you’re going !

This is the part of the story where you exit the ordinary world and enter the world of adventure.

If you’re writing a fish-out-of-water tale about an entitled starlet whose private plane crashes in the Ecuadorian paramo and has to find her way home against all odds, then THIS is the moment her plane crashes, and she’s in the paramo.

Before, she was in her cozy privileged life of plush seats, white leather, and multi-million-dollar movie deals. And now, she’s in an alien landscape where nobody speaks English, and nobody knows who she is.

Dorothy’s little house gets dumped in a colourful town square. She’s no longer in the black-and-white world. She’s now entered a land of technicolour.

Watch the video below and pay attention to how the sound design indicates that she’s entered a world of adventure.

STAGE 3 – STORY CIRCLE MOVIE EXAMPLE

Search: The Hero Begins the Journey and Must Adapt to the Unfamiliar World

You land in a new country without any language skills or understanding of the culture, and now it’s time to fake it ‘til you make it.

Will you survive?

Or will you fall apart?

According to Dan Harmon, “the point of this part of the circle is, our protagonist has been thrown into the water, and now it’s sink or swim.”

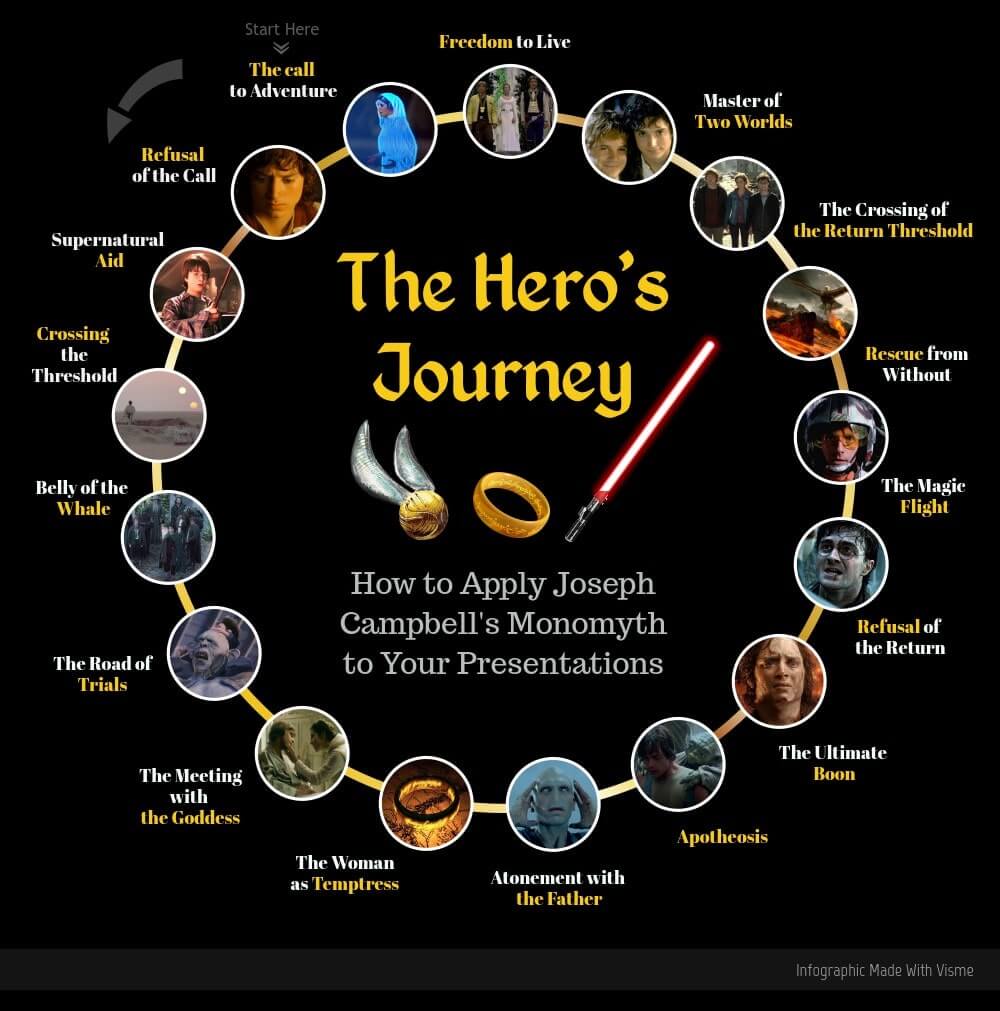

Joseph Campbell, the original story circle creator, i.e. the man behind the hero’s journey analysis, calls this phase in a story the Road of Trials. (+)

This is the phase in a story where your main character tries to get the lay of the land. They may meet new friends and mentors. They may be given a helpful aid critical to their future. They may learn new skills.

But most of all, they get beaten up emotionally—and sometimes physically too.

Yellow bricks are everywhere, and adorable human beings with odd singing voices greet her! Hurrah, she’s in the Land of Oz! But wait, now she has to figure out how to get back home. She needs to follow the yellow brick road. Just her and Toto on a road towards the great unknown. Dorothy begins her adventure.

STAGE 4 – STORY CIRCLE MOVIE EXAMPLE

Find: The Hero Gets What They Wanted, But It’s Not How They Expected

Mother, womb, emergence, transcendence, bliss, reckonings, vulnerability, bliss.

For months, maybe years, you’ve wanted something, and finally, you have a taste.

Let’s say you’ve always wanted to be rich. You’ve been scraping by for years. You graduate from university, and boom! Suddenly, you get a job that pays you 10x what you’ve been earning.

You’re working on Wall Street, making so much money you don’t know what to do with it.

But it doesn’t feel the way you thought it would. Instead of floating through life in blissful happiness, you’re grinding your teeth while you sleep and waking up with headaches. This is not what you bargained for, and you’re not sure what to do about it.

In this part of the story, the hero finds part of what they were looking for, but it’s not how they expected it to be.

This part of the story, as per the hero’s journey, is also the transcendent or “meeting the mother” stage. There is feminine energy at the bottom of the story circle.

In a romantic comedy, this is where the two lovers finally really fall in love or realize what love is all about.

In an action-packed drama, the hero would likely have a moment of rest and romance with a woman who represents his deepest desires.

According to Mr. Harmon, this part of the story circle is where our character is the most vulnerable. The following six concepts are all potentially part of the mix when you reach the bottom of the story circle.

- MEETING WITH THE GODDESS

- CONFESSIONS

- VULNERABILITY

- INTO THE PSYCHE

This part of the story is a major turning point.

It’s another threshold that the character must cross— as they do, the story takes an entirely new turn. The hero is now on the road HOME. They have come this far, and now they have to “screw their courage to the sticking place” and do everything within their power to fight their way home.

Fun fact: this stage in the story circle often involves water.

Pay attention to the next few movies you watch and see if there’s water involved in Stage 5! In the example below, it’s frozen water that’s used to create the moment of bliss.

Dorothy and her friends are near the end of their journey. The Emerald City is finally in sight. But the Wicked Witch of the West has placed a field of magical sleep-inducing poppies on the outskirts of the city, and Dorothy and Toto fall into a deep slumber. This heroine reference hints at the darkness that creeps within us all, particularly as we’re about to make our dreams come true.

This scene is a beautiful example of the fifth stage of the story circle.

As Glenda enchants the field with snow and the white flurries fall upon the field, Dorothy and Toto are revived.

STAGE 5 – STORY CIRCLE MOVIE EXAMPLE

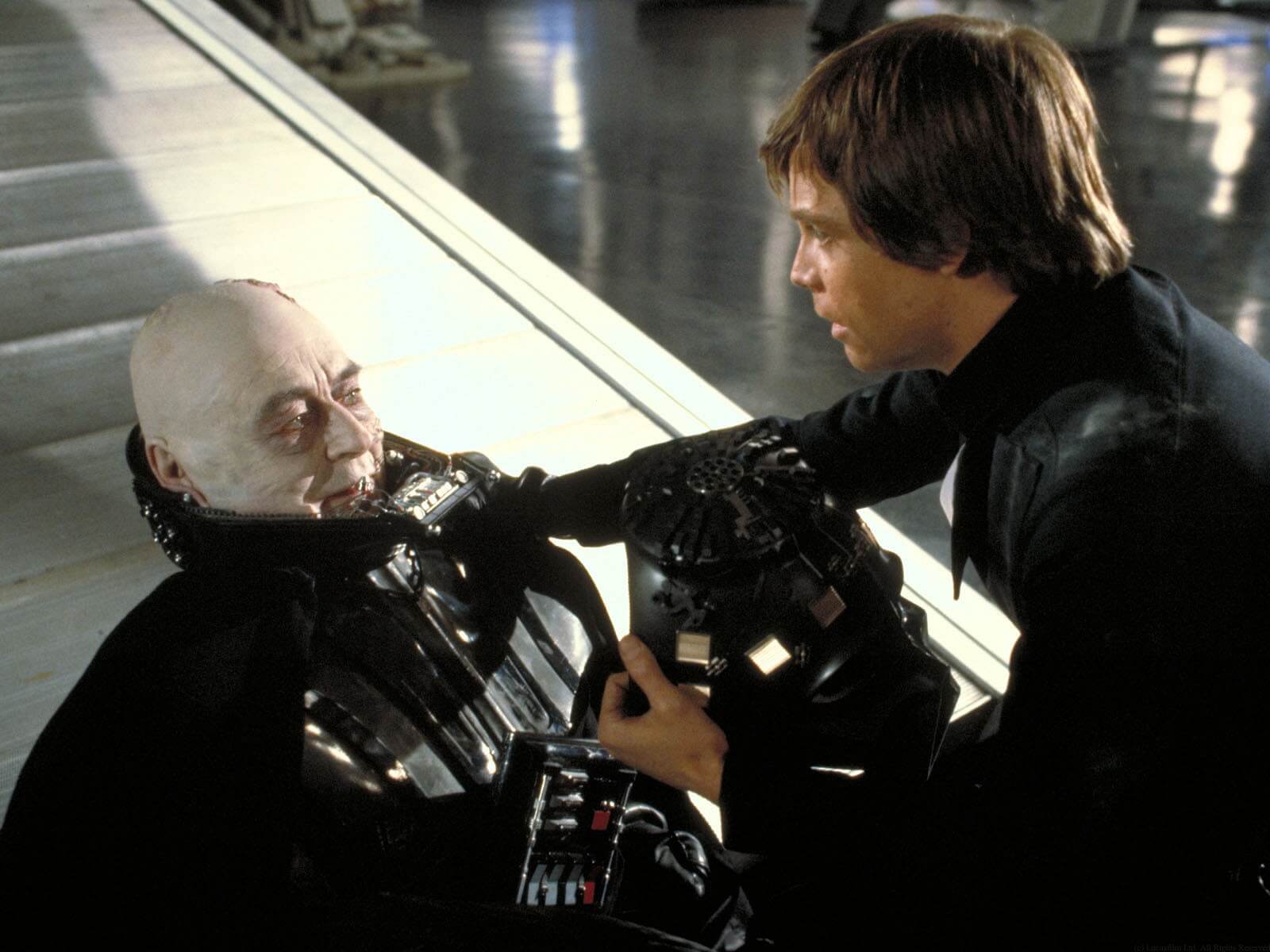

Take: Meet Your Maker, Facing the Father, the Vader Face Off

The hero battles to the next stage, paying a price for what they have won.

It’s time to meet your metaphorical (or real) maker.

This is the moment in the story where you face off with the villain and come close to real or metaphorical death. This climax is the culmination of everything the hero has been fighting for throughout the story.

If they make it through this face-off, they’ll be transformed.

Story Structure Examples:

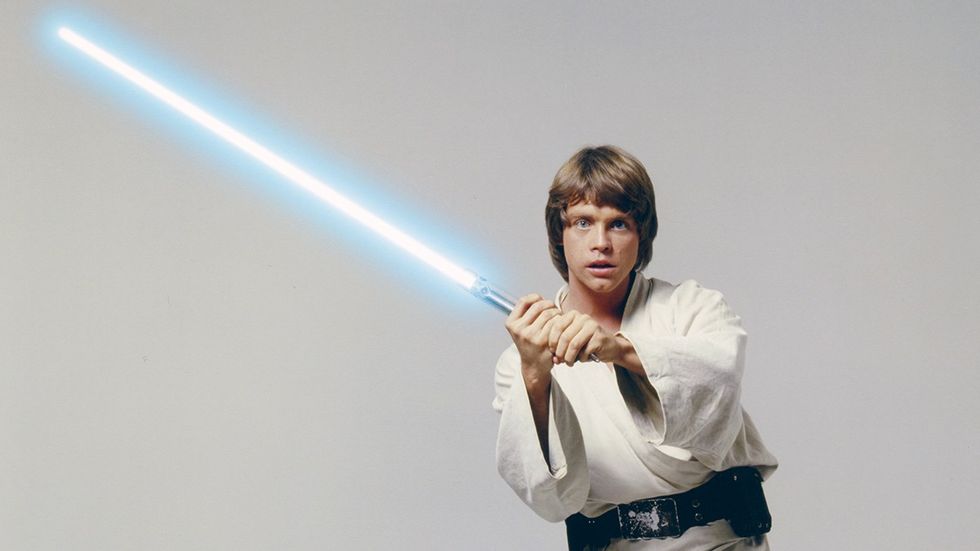

- Luke Skywalker faces Darth Vader.

- Peter faces Hook as he frees Wendy and the boys.

- The Titanic is sinking— Jack and Rose face a wall of water that could eat them alive.

- Dorothy faces the Wicked Witch of the West.

STAGE 6 – STORY CIRCLE MOVIE EXAMPLES

Return: The Flight Home

You’ve gotten what you needed, defeated the villain, learned something about yourself, and now you’re ready to return home with your new knowledge. But not so fast!

This is the part in a romantic comedy where the hero chases after the one he (or she) loves. He races to the airport to make sure his soul mate doesn’t get on that flight.

In an action movie, the hero has just defeated the villain and must head home, sometimes chased by more attacking gremlins.

Dorothy discovers the wizard is a fake. But luckily, it turns out there’s still a way to get home. It turns out that the pathway to getting home had been on Dorothy’s feet the entire time. She clicks her heels three times and repeats, “There’s no place like home.”

Titanic Story Structure Example:

Rose lies on the wooden board, the night is cold, and she’s nearly frozen. Then flashlights pierce the darkness. A boat has arrived. She and Jack can go home. She turns to Jack to wake him up, but he’s cold to the touch. Jack has died. But Rose can still go home. Broken-hearted, she nearly gives up. But at the last minute, as the boat is gliding away, Rose calls out. She leaves her raft and swims towards the boat and the possibility of going home.

STAGE 7 – STORY CIRCLE MOVIE EXAMPLES

Change: The Hero Has Transformed and Brings New Gifts to their World

You’re home now after your 300-day trip around the world.

You’re no longer the same. You’ve learned things about yourself and the world you can never unlearn. You’ve tested your strength and courage. You have wisdom to share and are happy to be back in the ordinary world. This transformation you’ve undergone in your journey into the unknown and back is irreversible.

Dorothy finally realizes that her home and family are the most valuable treasures on earth. She’s no longer the dreamy girl who wishes to be far away. She’s grateful for what she has and sees treasure in the simple things. She is transformed.

STEP 8 – STORY CIRCLE MOVIE EXAMPLE

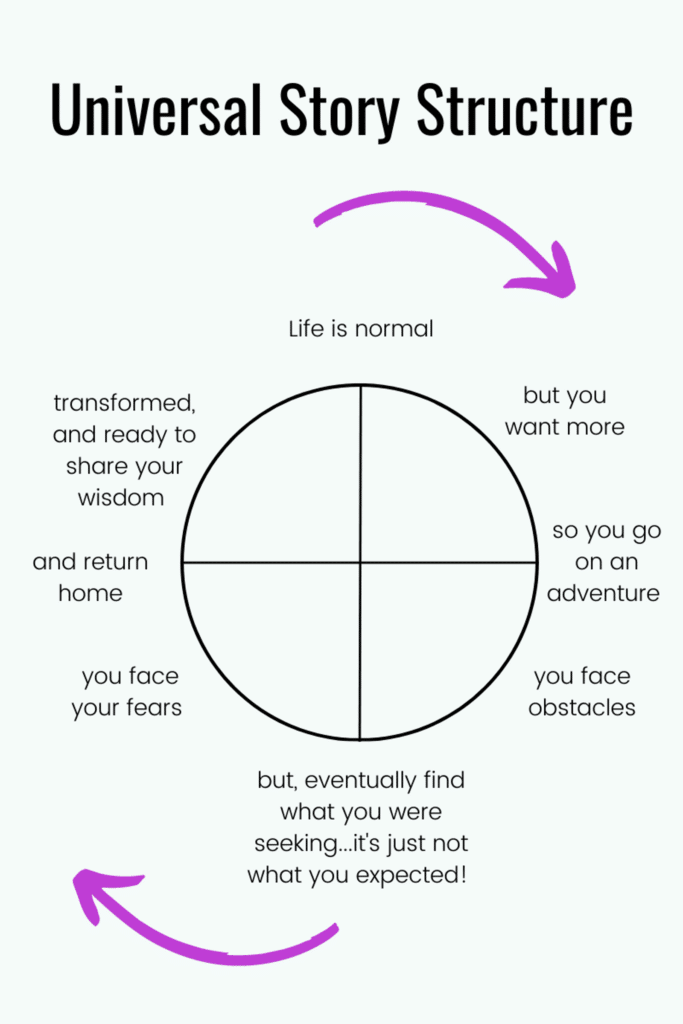

There is a basic universal structure to a good story.

The hero starts out in their regular world. Things are normal. Perhaps they are unfulfilled.

Early in the story, the hero develops a burning need.

They want something, but there are obstacles in the way. To get into the meat of the story, the hero has to answer the call and race across the threshold into the World of Adventure.

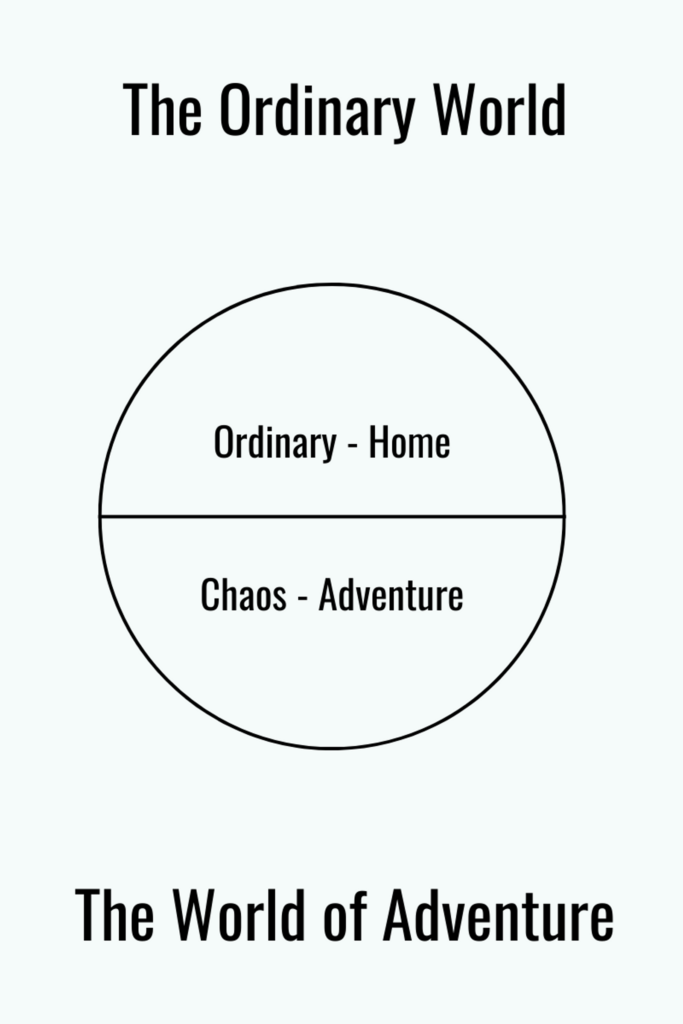

There are two slices to the story circle.

You can cut your story circle in half vertically and horizontally. On the top is the regular world, and on the bottom is the world of adventure.

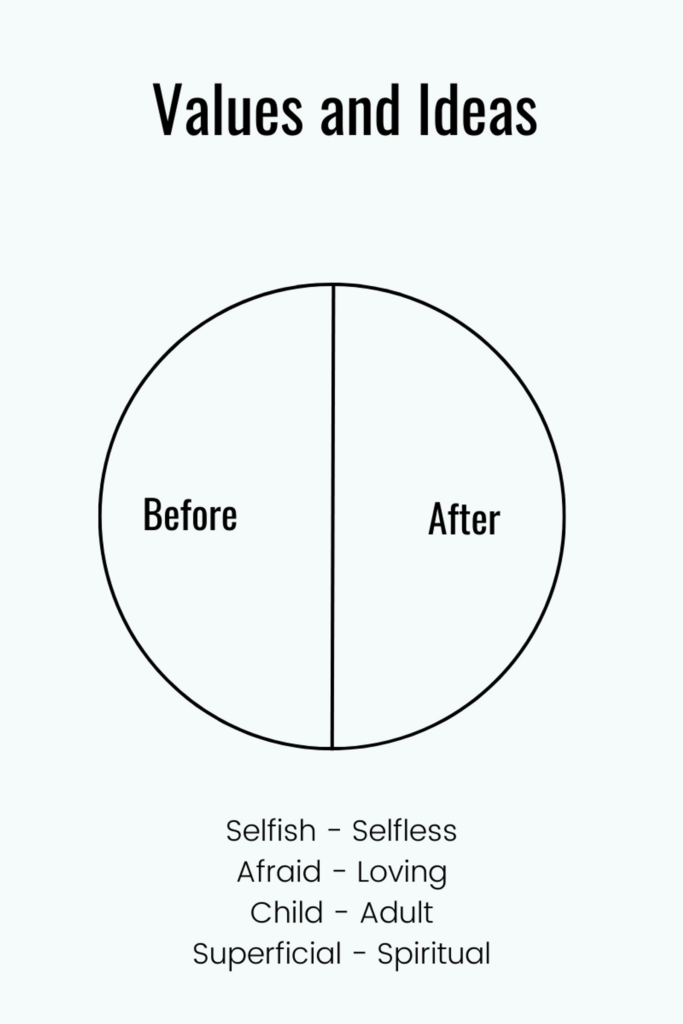

Meanwhile, when you cut your story circle in half vertically, the left side is the starting idea or value, and the right side is the ending idea or value i.e. the transformation.

Can you see how if you use the story circle, you can quickly test your story and see if it works?

The horizontal slice represents the moment the hero crosses the threshold into a new world, out of her comfort zone, and into the mud.

And near the end of the story, it represents her return to the familiar world again. The top half of the story circle is the Regular World. The bottom half of the story circle represents the World of Adventure.

It wouldn’t be a story if you didn’t end up in The World of Adventure.

The reason we love stories so much is that they transport us. They take us out of the everyday grind. They show us who we can become if we take a leap of faith and follow our dreams, passions, and inner guidance.

When you split your story circle in half horizontally, you see how the hero must cross the threshold, passing from the regular world into the world of adventure.

For the story to get going, the hero must enter a quagmire of challenges.

The character enters an unfamiliar situation.

They are now in the World of Adventure. They are no longer stuck or stagnant. They are NOT in their comfort zone any longer. They’ve stepped out onto the rickety bridge and are moving forward, one foot in front of the next, creeping over the abyss.

They adapt to the situation.

This is the part in the story where the hero meets friends and foes and gains tools and tricks that they can use to defeat their enemy in the future.

You could think of this as the training stage.

In your own life, when you embark on a new adventure, there’s a stage where you’ve landed in the new world, and you have to learn the ropes.

You start a new job, and you have no idea what the hell you’re doing.

You meet new co-workers, figure out who the crazy people are, and learn how to use the weird 1980s coffee maker they inexplicably have in the break room.

Joseph Campbell called this stage of the Hero’s Journey the Road of Trials.

The final part of the story circle is the vertical cut.

On the left, you have the idea or value that drives the character and the story from the beginning. On the right, you have the idea or value that takes over after the character lives through the moment of reckoning or meeting with the goddess.

If you begin the love story guarded, unwilling to trust your heart with anyone, after you experience a true-love kiss, you change.

You begin to act out of love instead of fear.

You’re no longer guarded; you’re driven by a desire to love and be loved.

If you begin a coming of age story as a selfish, bratty, spineless child, you will cross the threshold at the bottom of the story circle and move into adulthood. You are no longer in it for yourself alone; you fight for others and give of yourself selflessly.

If your story can’t be split into two opposing values, it will lack tension.

Common Story Circle Questions:

When you’re writing a story or coming up with the plot points for a screenplay or video, it’s common to get lost or stuck.

Although storytelling is a natural part of how we share the moments in our lives with friends and family, when doing it formally, things can go sideways fast.

So, let’s answer some of your pressing story circle questions!

When should you use Dan Harmon’s story circle?

You should use Dan Harmon’s story circle and the Hero’s Journey structure whenever you’re crafting a story.

Before you start writing a story or script, create an outline of the structure and use Dan Harmon’s story circle to test your idea. Make sure that you have all the basic structural elements before you start writing.

What is a story circle?

A story circle is a way of breaking down your story’s structure to identify if your story works.

The story circle is based on Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. It is Dan Harmon’s simplified version of the hero’s journey and is a simple structural analysis tool for storytellers.

What is the concept of the story circle?

The basic concept of the story circle is that every story follows a universal pattern.

Every story starts with a main character that has a need, goes on a journey into a world of adventure and is changed through facing challenges.

How many steps are in a story circle? And what are the steps?

There are eight steps in the story circle.

- You – A main character in the ordinary world

- Need – Has a need and a desire to take action

- Go – They leave their ordinary world and take decisive action

- Search – The hero searches for what they need, facing obstacles

- Find – They find what they were looking for, but it’s not what they expected

- Take – They pay the price and face their mortality as they take what they need

- Return – Finally, the hero can return home

- Change – Transformed and ready to share their wisdom

Where did the story circle come from?

The story circle came from Dan Harmon’s obsession with storytelling and his need for a simple story structure tool that could help him while writing hundreds of television episodes.

Did Dan Harmon create the story circle?

Dan Harmon created the story circle based on Joseph Campbell’s analysis of the hero’s journey.

Become a Confident Storyteller

Hi, I’m Colette Nichol! I’m a video producer, story strategist, and solo filmmaker based out of Vancouver, Canada.

If you’re interested in becoming a confident storyteller, check out my online storytelling course Story Guru .

Or read more of the storytelling articles on the blog:

📖 Top 10 Elements of a Story

📖 How to Tell a Captivating Story

📖 What Story Should I Write?

📖 How to Write a Logline for a Movie

About the Author

Hi! I’m Colette Nichol . I’m a solo filmmaker and story strategist based out of rainy Vancouver, Canada. I’ve been making videos and micro films for small businesses and global brands since 2014.

Plus, I LOVE to help aspiring filmmakers pursue their dreams and start making films. This blog is designed to help you gain the knowledge you need to become a filmmaker.

If you want more, get on the waitlist for the Story Envelope Academy Solo Filmmaking Mentorship Program. It opens up one time per year and is the best way to become a filmmaking or video pro fast!

CLICK HERE to get on the solo filmmaking mentorship waitlist.

I'm Colette Nichol!

Welcome! I’m a story strategist, SEO consultant , filmmaker , and digital media consultant based out of rainy Vancouver, Canada. My mission is to give you the tools and tactics you need to achieve your dreams! If you're here for filmmaking training, please join the inbox party: take my free mini-course and start building a filmmaking and video creation skill set.

ahoy there!

Browse By Category

FILMMAKING TECHNIQUES

FILMMAKING BASICS

STORYTELLING

SEO FOR SMALL BUSINESS

LEARN FILMMAKING

VISUAL STORYTELLING

Elevating messages that matter. Tell your story. Share your vision. Grow your global audience.

STORY ENVELOPE MEDIA

CONTACT >

GET FREEBIES >

FILMMAKING COURSE >

© STORY ENVELOPE MEDIA 2021 | Photos by social squares & Unsplash & COLETTE NICHOL | TERMS OF SERVICE

Storytelling 101: The Dan Harmon Story Circle

The Story Circle by Dan Harmon is a basic narrative structure that writers can use to structure and test their story ideas. Telling stories is an inherently human thing, but how we structure the narrative separates a good story from a truly great one.

Because of Dan Harmon’s background in screenwriting, the Story Circle is popular among filmmakers and writers on TV shows and TV series, but any storyteller can benefit from using it. Let’s look at this narrative structure more closely, examine the eight steps, and discuss its use in story and character development!

What is the Dan Harmon Story Circle?

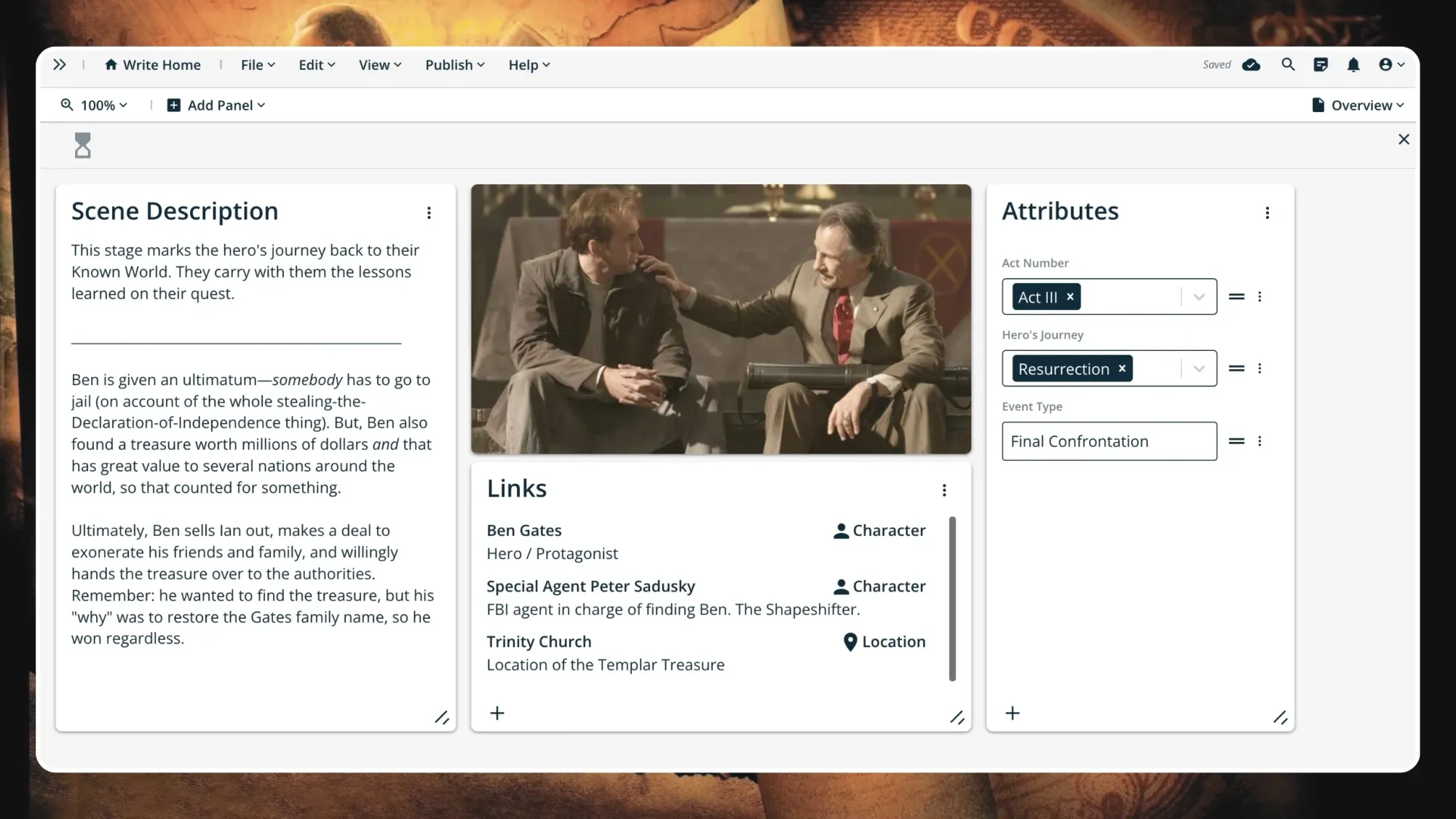

The Dan Harmon Story Circle describes the structure of a story in three acts and with eight plot points, which are called steps. When you have a protagonist who will progress through these, you have a basic character arc and the bare minimum of a story—the story embryo or plot embryo, if you will.

The Story Circle as a narrative structure is descriptive, not prescriptive, meaning it doesn’t tell you what to write, but how to tell the story. The steps outline when the plot points occur and the order in which your hero completes their character development. These eight steps are:

1. You A character in their zone of comfort

2. Need wants something

3. Go! so they enter an unfamiliar situation

4. Struggle to which they have to adapt

5. Find in order to get what they want

6. Suffer yet they have to make a sacrifice

7. Return before they return to their familiar situation

8. Change having changed fundamentally

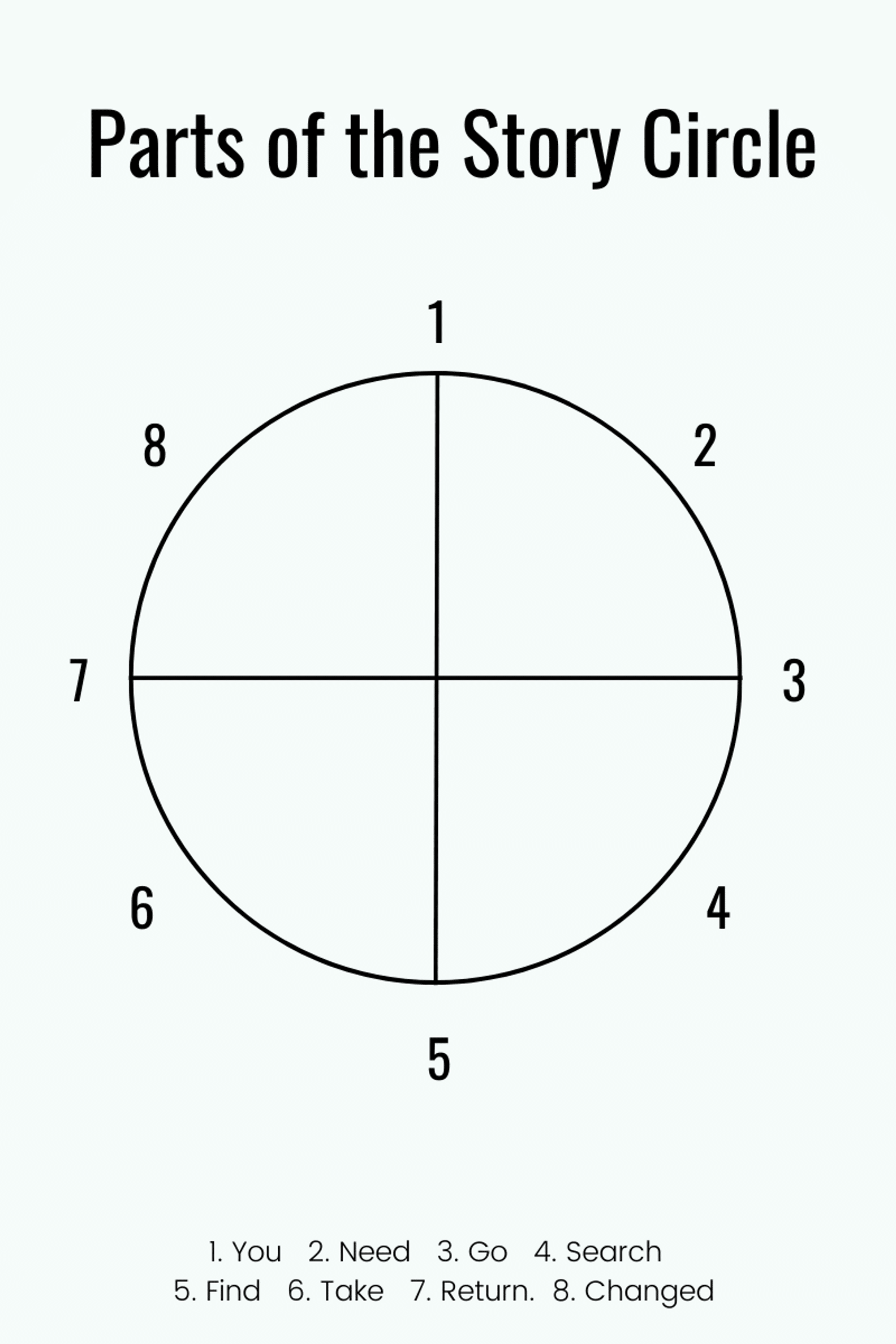

The hero completes these steps in a circle in a clockwise direction, going from noon to midnight. The top half of the circle and its two-quarters of the whole make up act one and act three, while the bottom half comprises the longer second act. In their consecutive order, the Story Circle describes the three acts:

Working with the Story Circle enables you to think about your main character and to plot from their emotional state. The steps will automatically make your hero proactive as you focus on their motivation, their actions and the respective consequences.

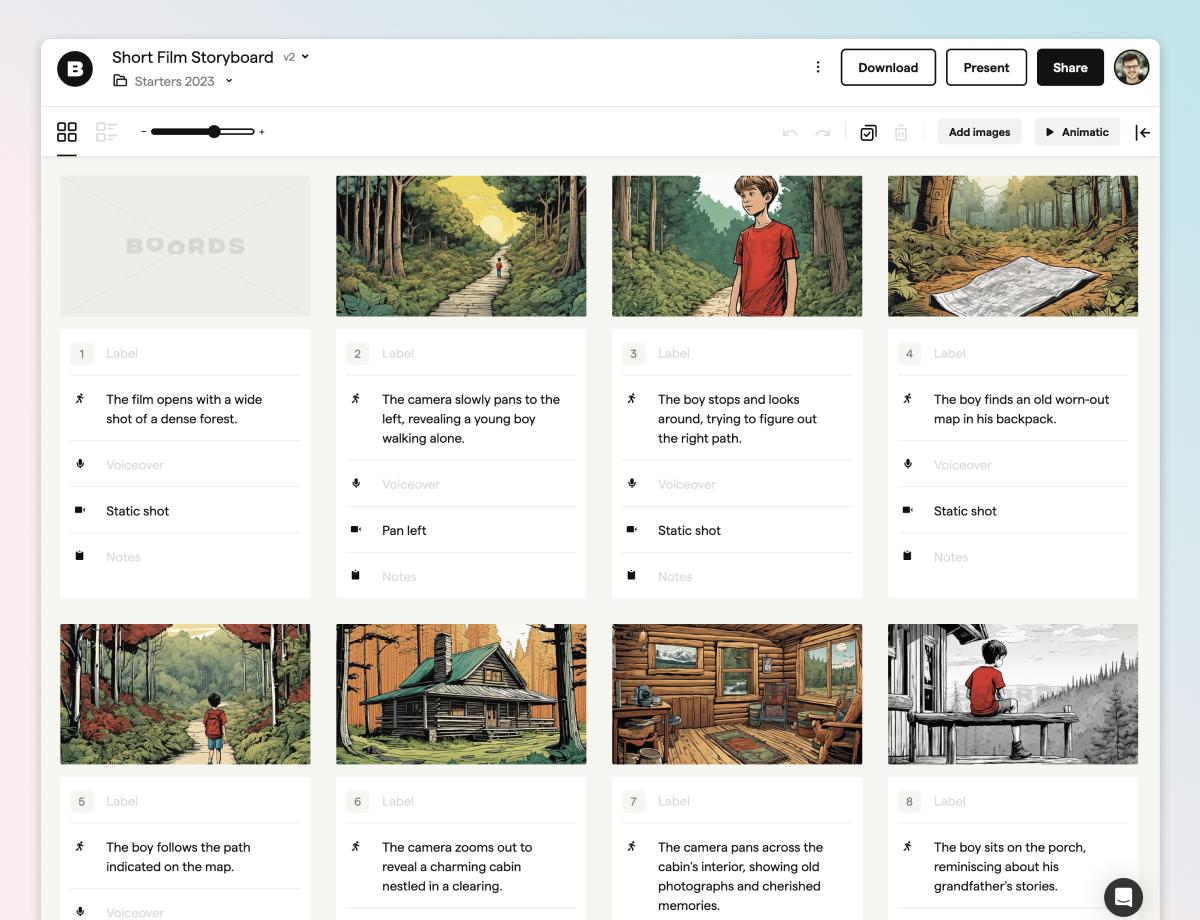

The Shortcut to Effective Storyboards.

Boords is an easy-to-use storyboarding tool to plan creative projects.

The Story Circle in story structure theory

Why is this narrative structure a circle? A classic graph of the three-act structure charts the rising and falling action with its plot points as a line with peaks, so why can't your hero complete the eight steps in a linear fashion from the beginning to the end?

The Hero’s Journey

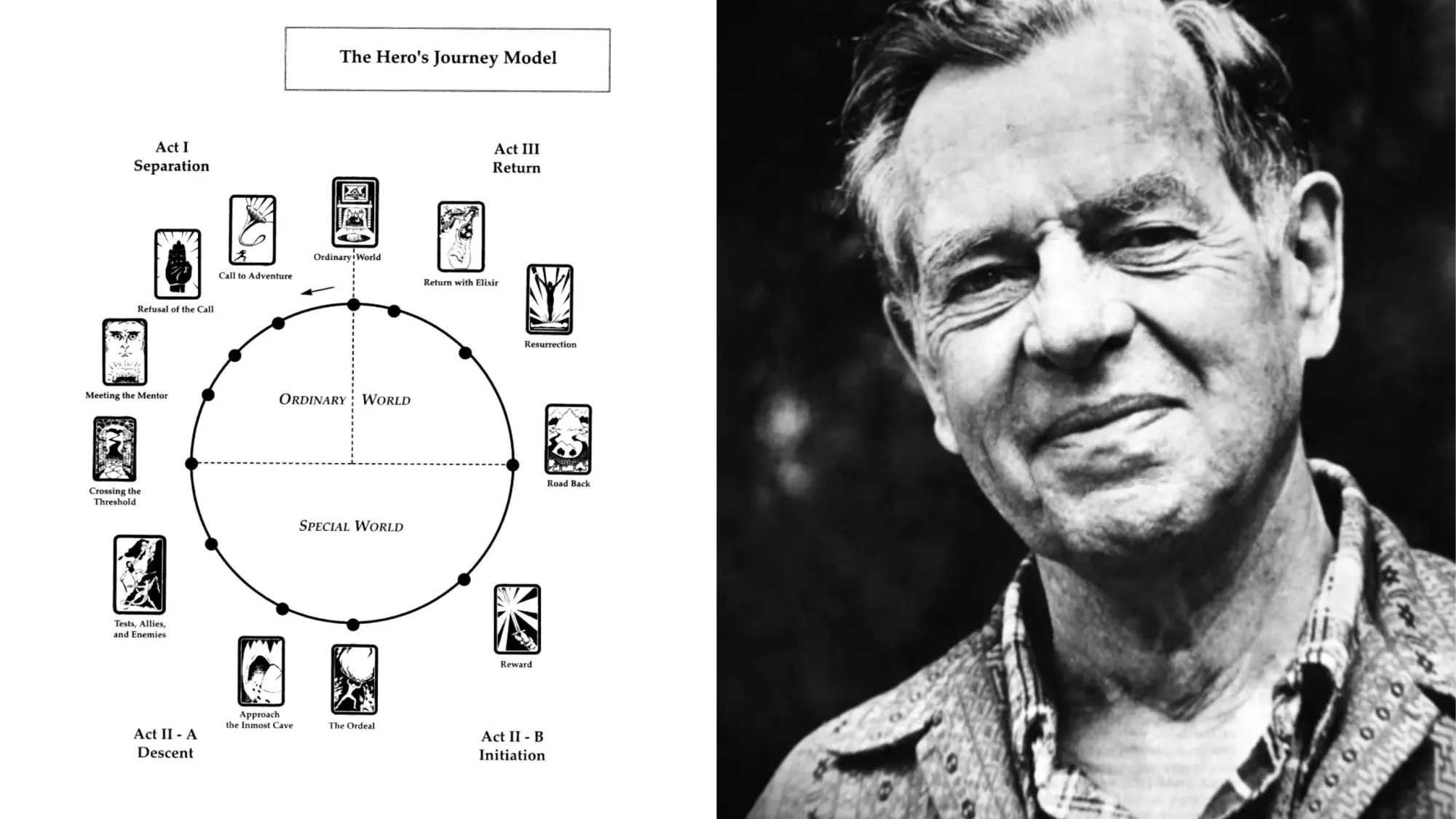

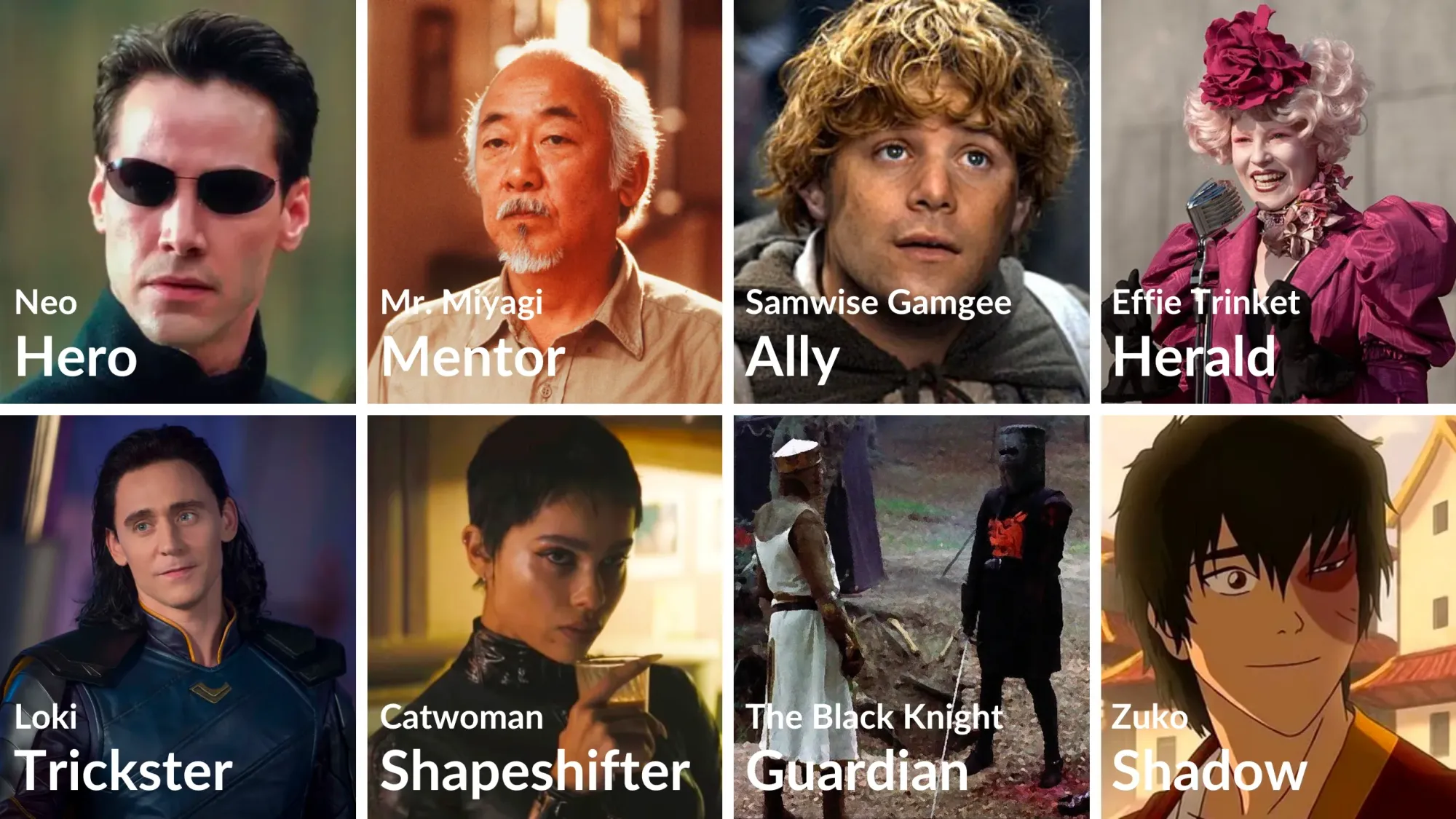

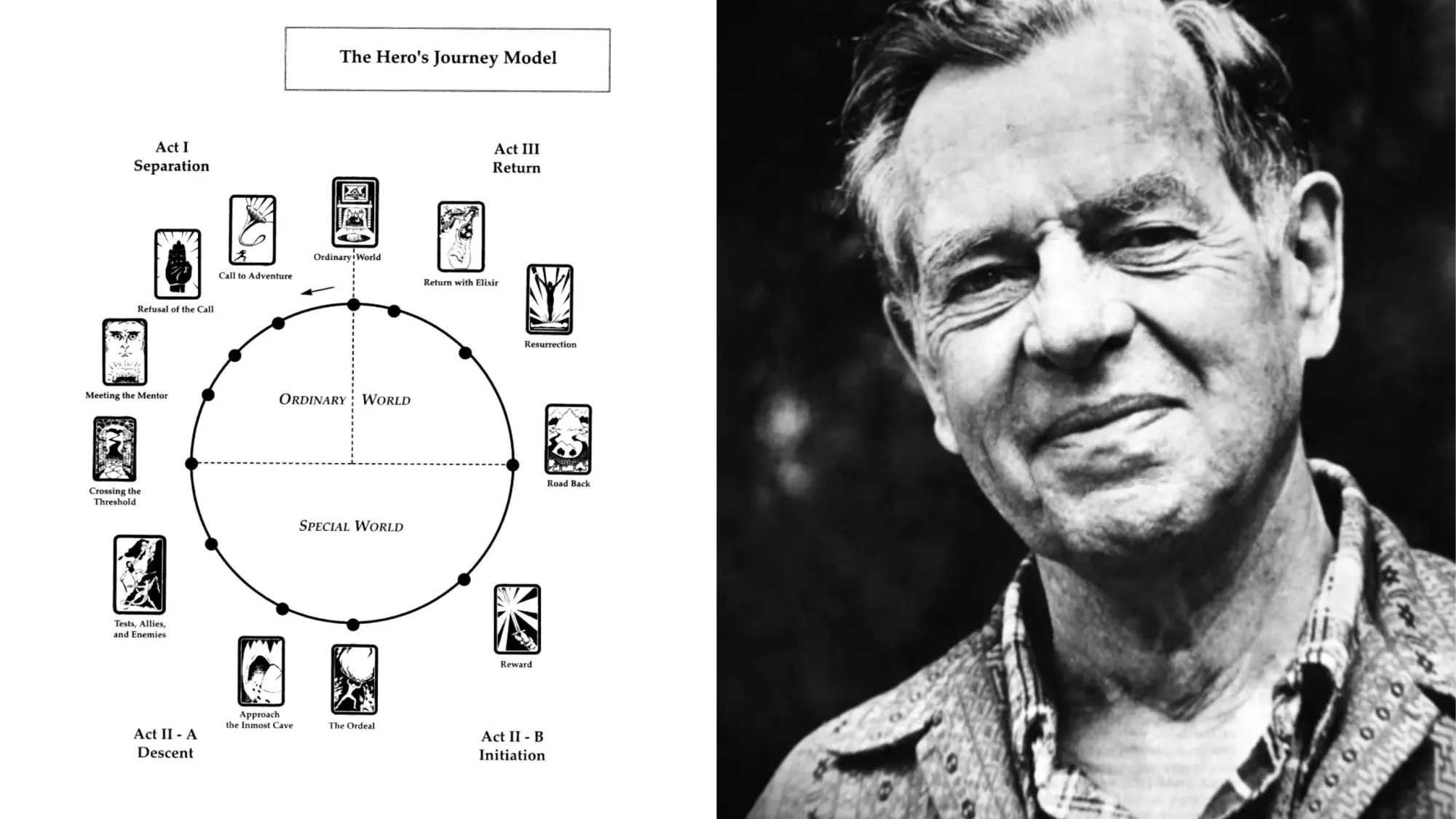

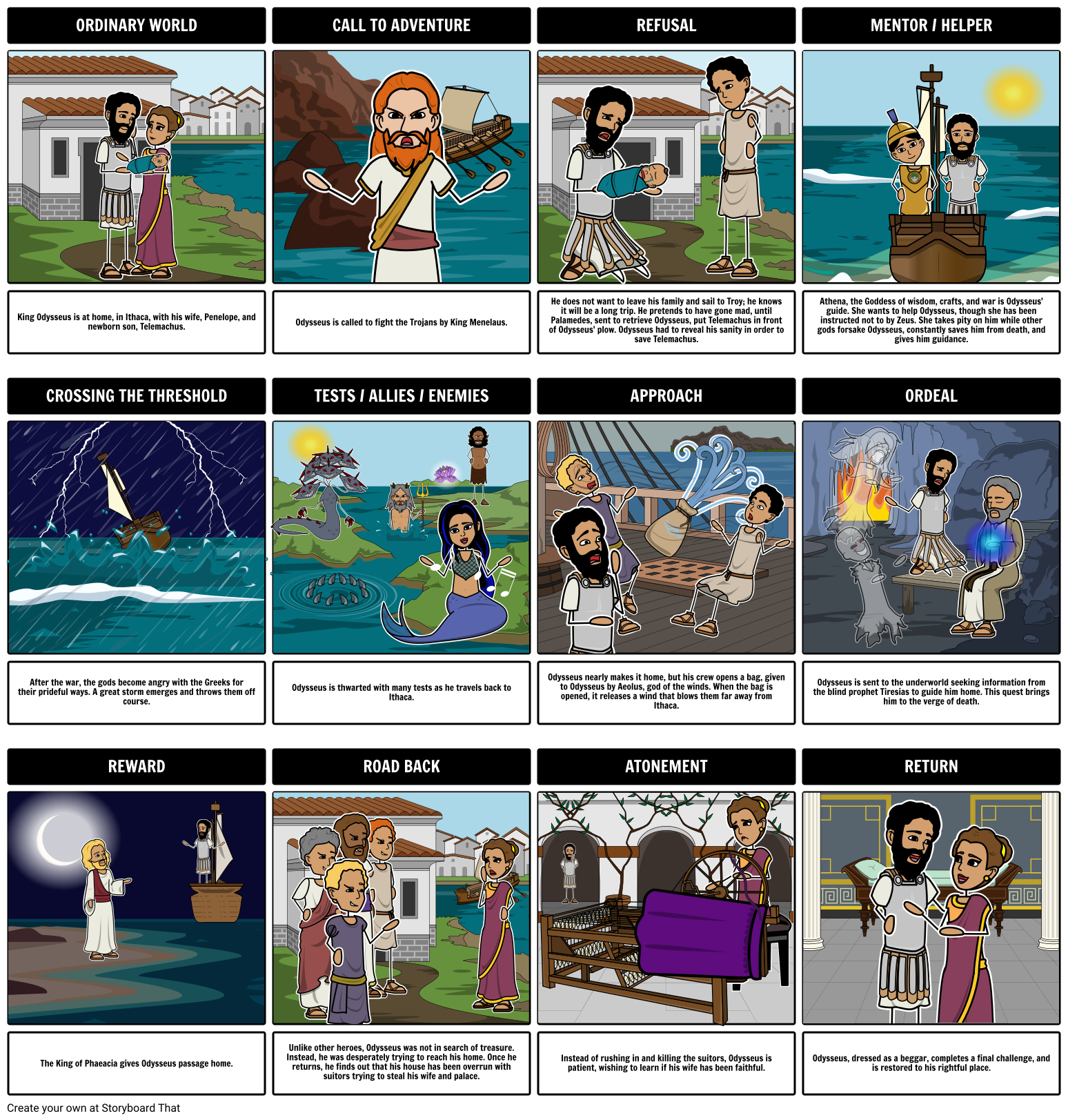

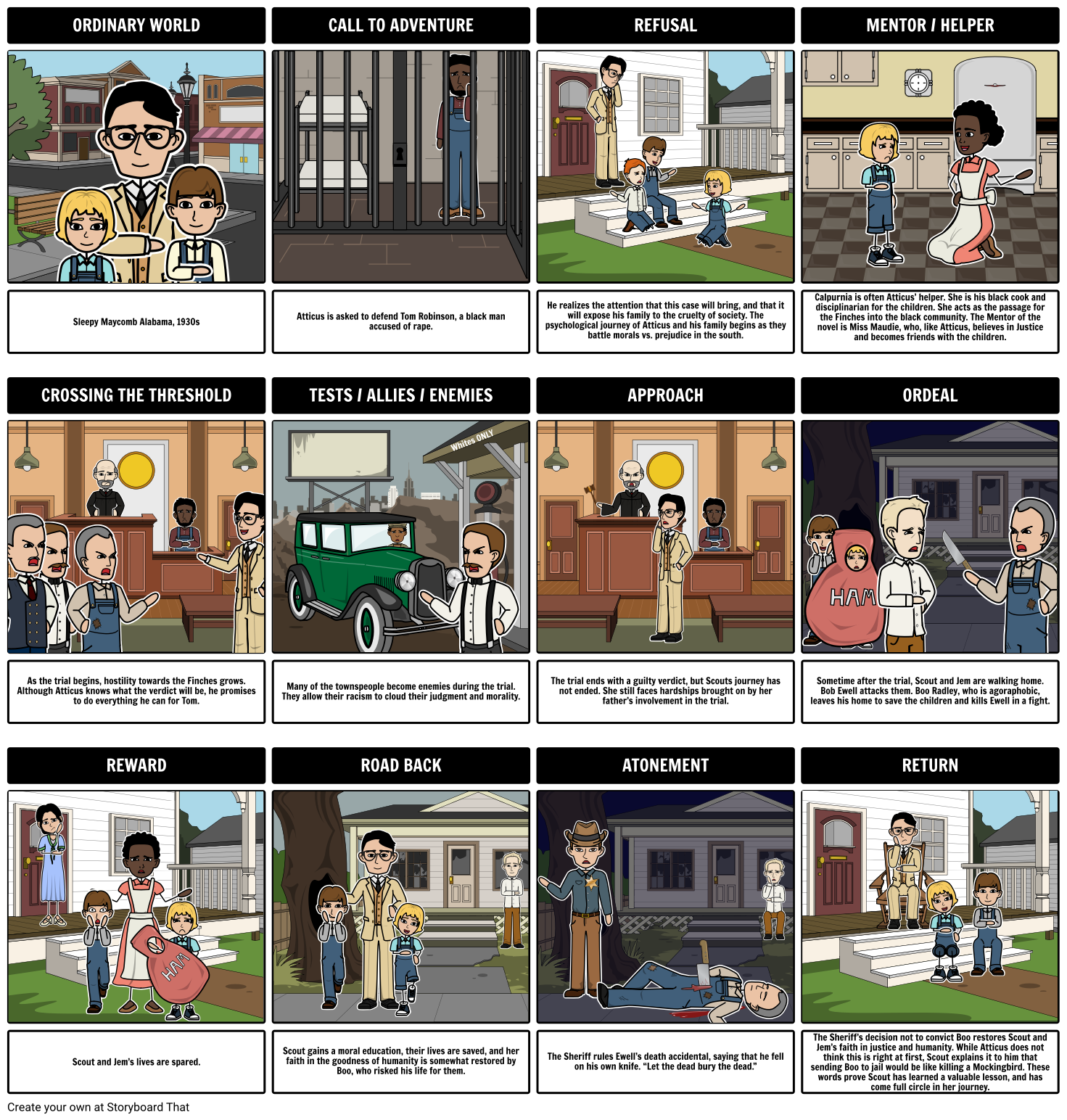

Dan Harmon hardly invented the circular narrative structure or traced the cyclical nature of stories in the three-act structure. He merely simplified the Hero’s Journey and adapted it to his own screenwriting needs. The hero’s journey is a template of stories that describes the stages of a hero embarking on a quest or adventure, who has to go through crisis before victory to emerge transformed. Though the hero often brings back an “elixir”, the solution to their initial “problem”, it’s their inner change that enables them to prevail in the “new order” at home.

The monomyth

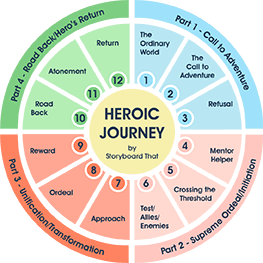

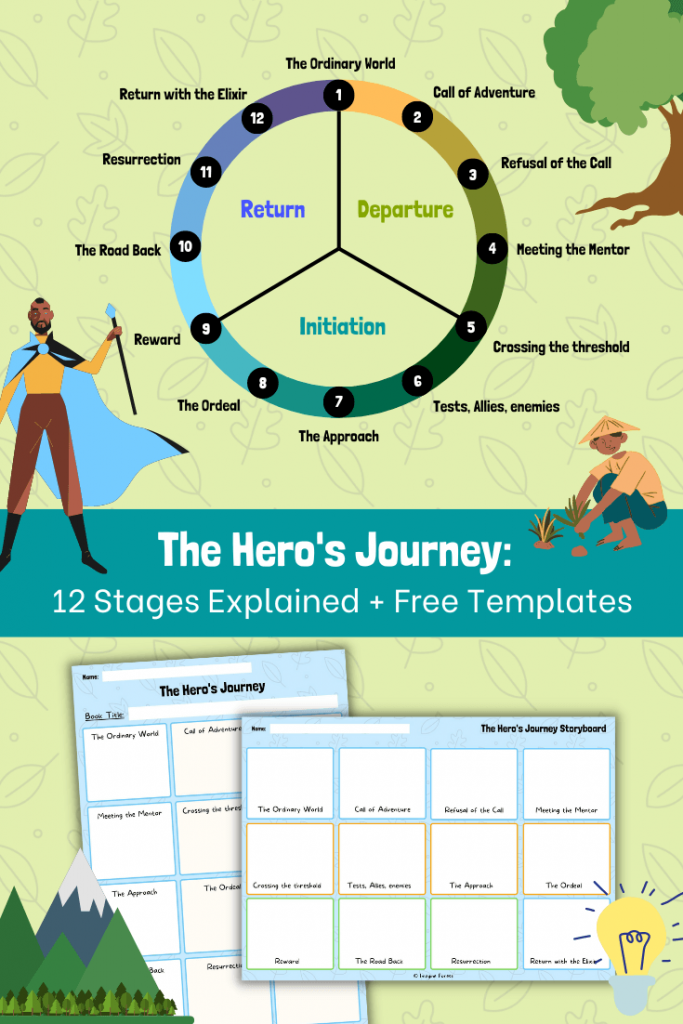

The return as expressed in the circle is essential to the monomyth , which is a concept of mythology described by the American writer Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces . The monomyth sees common narrative structures in all great myths. Campbell names the three acts Departure , Initiation , and Return , and charts the Hero's Journey over 17 stages. Hollywood executive and Disney screenwriter, Christopher Vogler, reduced the number to 12 steps in The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers .

Simplification of steps in the circle

Interestingly, American philologist David Adams Leeming in 1981 and American screenwriter and filmmaker Phil Cousineau in 1990 both used only eight steps for their adaptation of the Hero’s Journey. Dan Harmon developed his Story Circle in the late 1990s when he was stuck on a project. He cites Christopher Vogler and the screenwriting author Syd Field as influences.

The Hero’s Journey in screenwriting

The Hero's Journey, the monomyth and Joseph Campbell are popular in Hollywood filmmaking. George Lucas used the template for Star Wars , you can read The Matrix trilogy by the Wachowskis as an extensive study in mythological storytelling, and Pixar movies such as Finding Nemo exhibit monomyth story structure.

Save the Cat

Screenwriter and author Blake Snyder omitted the circular structure in his work, but his book Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You'll Ever Need also takes the Hero’s Journey and breaks it down into 15 essential story beats or plot points.

What else is Dan Harmon known for?

Daniel James Harmon (born 1973) is an American writer, producer , and actor known for the sitcom Community and the animated series, Rick and Morty . In episode S4E6 “Never Ricking Morty” the two characters find themselves aboard the circular Story Train and the episode pokes meta-fictional fun at the narrative structure. Dan Harmon also created and hosted the comedy podcast Harmontown . In 2013, Harmon published the book, You'll Be Perfect When You're Dead .

The 8 steps of the story circle

You. Need. Go. Struggle. Find. Take. Return. Change. The way the story circle works is that your main character, much like Campbell’s hero, moves from a zone of comfort towards a want, and with that, into the chaos of the second act, from where they’ll return changed. The top half of the circle represents order and the bottom half chaos. The right side of the circle represents the hero resisting their transformation, the left side represents the hero moving towards their transformation.

In this cyclical nature of storytelling, you can see the main character gain and lose: they gain their want, but lose stability; they lose in the struggle, but ultimately find what they want; they pay a heavy price for it, but can bring it back home; the old order cannot be again, but they have changed to exist in the new order.

1. A zone of comfort

The first step establishes the hero of your story in their familiar surroundings. Think of it as a 'before' picture. Note that "zone of comfort" doesn't mean things are perfect. Your main character exists in a status quo in which they have arranged for themselves to fit into their current conditions.

The 'before' picture is important for the character arc so that viewers can recognize the significance of the change later. Interesting main characters are not perfect, either, but exhibit human flaws the audience can understand and sympathize with.

For the second step, you dangle something in front of your main character: desire is something they want as a thing to obtain or a problem they want to go away.

The desire becomes the main goal of the protagonist, but their next actions are decided in a "push" or "pull" fashion: if the desire is pulling them out of the status quo, then they might prepare for the journey (think: Harry Potter getting his supplies). If they're being pulled out of their comfort zone and would rather stay where it's nice and warm, then they debate how they can avoid having to go.

"Desire" can take the form of a problem or an adversary in the sense that the hero would very much like for the antagonist to disappear so they could return to the status quo right away.

3. Entering an unfamiliar situation

In step three, you kick off the action: green means go! Your hero is proactive: even when they've been debating and their desire is of a "pull" nature, they still make a conscious decision and take the first step themselves. This step also signifies the crossing of the threshold from order into chaos, from the first into the second act.

Their new surroundings are unknown and they find themselves in an unfamiliar situation, which can be hostile, or simply something they’ve never experienced before: it’s the figurative (or, with Stranger Things , literal) upside-down of their initial surroundings.

4. Adaptation

Your hero may or may not like the chaos in their new world, but the only way out is through. As a storyteller you throw increasingly bigger obstacles in their way and put them through many trials and tribulations, forcing them to adapt as they struggle to overcome the hurdles.

What's important: the way back is barred, because the old home is so much worse (up to where return signifies death), or because there is another insurmountable concrete or abstract obstacle.

5. Attaining the object of desire

At the halfway point, you let your hero have what they desire. Reading the Story Circle like a clock, it's now 6 PM and high time to return home. Step five, as the crucial finding step, raises the stakes of the story.

Your main character has completed the search, found what they wanted, and is holding the (metaphorical) key in their hands — but the lock which it turns is half a world away! Can they make it back, and in time? To increase tension, many stories introduce time constraints here, such as a countdown of any sort, a sick or wounded companion, or the environment turning on the main character.

6. A heavy price to pay

Your hero takes what they want, but something is taken from them. Before they can go on, they must leave something behind. This loss can take many forms: a temporary, albeit despairing setback which leaves the hero stranded; the death or sacrifice of a companion character; losing "innocence"; having to give up any integral part of themselves, from limb to memories.

This step marks the absolute low point in the journey of your hero. The heavy price is so hefty that they seriously doubt if carrying on is even worth it. There are many names to describe this moment, from figurative death (of the old hero) to the “dark night of the soul” or the darkest hour.

7. Return to the familiar situation

Your hero finds it within themselves to complete the journey and return home to their familiar situation. However, within themselves is key here! Note that with step seven, your main character crosses back into the upper half of the circle, leaving the chaos of the second act behind. Yet this threshold doesn’t come without a trial of its own.

In ancient myths, when the protagonist returns, they often face a gatekeeper, a riddle to solve, or proof that they are who they say they are. Although they surely have changed externally, it’s their internal transformation that allows them to pass this test. Even when the magic “key” is a concrete object, such as an “elixir”, only they can wield or apply it.

The familiar situation is often only seemingly familiar and externally changed as well, because the hero has been presumed dead, their old surroundings have been transformed or old friends have moved on with their lives.

8. Fundamental change

The application of the “solution” by your hero to establish the “new order” brings with it the realization that they are not the same person anymore: they have changed from the beginning. This is where you do a second snapshot and show the ‘after’ picture.

Change can be for the good and your main character is now wiser, better, more mature, no longer alone, or richer in some sense; but the ending can also be tragic, and though they have brought better circumstances for someone else, they are now morally corrupt, filled with despair, utterly alone, or at the end of their life.

Get your FREE Filmmaking Storyboard Template Bundle

Plan your film with 10 professionally designed storyboard templates as ready-to-use PDFs.

How to use Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

In conclusion, let’s note again that Dan Harmon’s Story Circle, like all story structures, is best understood as primarily descriptive; approaching screenwriting with such a ‘template’ seems formulaic, but the structure doesn’t prescribe to you as a writer the story to tell, only how. You can take Snyder’s beats or the Dan Harmon Story Circle and overlay the structure over any existing film (with a story in the traditional sense): from Harry Potter to anime movies to early cinema, you’ll be able to match the steps to the action or the script.

As a screenwriter working on a feature film, TV series or TV show, you can begin plotting the character arc of your hero with the eight steps we’ve outlined above. Gather your ideas and see what sticks, or test an existing story idea with the eight steps: are your stages ‘strong’ enough? Pay attention to the three quarters, or noon, 3 pm, 6 pm, and 9 pm, when you read the Story Circle like a clock. They’re essential to moving your story forward in a believable way.

If your story doesn’t seem to pick up any momentum and you struggle to progress your main character through the steps, you might need to work on your hero more. Are they proactive enough? Is their desire big enough? Are the upper and lower half of the circle opposites, and are the left and right half contrasting enough?

For more theoretical background, you can read up on the Hero’s Journey by Joseph Campbell, and for a fun, practical exercise, watch a favorite movie and plot the steps of Dan Harmon’s Story Circle for it!

Related links

Online storyboarding software

The Shortcut to Effective Storyboards

Boords is the top-rated online storyboarding software that makes planning video projects a joy, not a job.

Passion doesn’t always come easily. Discover your inner drive and find your true purpose in life.

From learning how to be your best self to navigating life’s everyday challenges.

Discover peace within today’s chaos. Take a moment to notice what’s happening now.

Gain inspiration from the lives of celebrities. Explore their stories for motivation and insight into achieving your dreams.

Where ordinary people become extraordinary, inspiring us all to make a difference.

Take a break with the most inspirational movies, TV shows, and books we have come across.

From being a better partner to interacting with a coworker, learn how to deepen your connections.

Take a look at the latest diet and exercise trends coming out. So while you're working hard, you're also working smart.

Sleep may be the most powerful tool in our well-being arsenal. So why is it so difficult?

Challenges can stem from distractions, lack of focus, or unclear goals. These strategies can help overcome daily obstacles.

Unlocking your creativity can help every aspect of your life, from innovation to problem-solving to personal growth.

How do you view wealth? Learn new insights, tools and strategies for a better relationship with your money.

Hero's Journey: A Guide to Becoming The Hero Of Your Story

What will your story be.

Be the hero of your story . It’s common advice from motivational speakers and life coaches, a call to arms to take centre stage and tackle life’s challenges head-on, to emerge victorious in the face of adversity, to transform through hardship.

As humans, hardwired to view the world and share experiences through the medium of stories, myths often act as powerful motivators of change. From ancient cave paintings to the Star Wars and its Death Star to Harry Potter and his battle against evil, the hero’s journey structure is a familiar one. It’s also one you need to know if you want to know how to write a book , but I digress.

This article will outline the stages, and psychological meaning, of the 12 steps of Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey. So, are you ready to become the hero of your story? Then let the adventure begin...

Who is Joseph Campbell?

Joseph Campbell was an American professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College, and an expert of mythology that once spent five years in a rented shack, buried in books for nine hours each day. His greatest contribution is the hero’s journey, outlined in his book The Hero with A Thousand Faces . Campbell was able to synthesise huge volumes of heroic stories, distilling a common structure amongst them.

Near the end of his life, Campbell was interviewed by Bill Moyers in a documentary series exploring his work, The Power of Myth .

Throughout their discussion, Campbell highlighted the importance of myth not just in stories, but in our lives, as symbols to inspire us to flourish and grow to our full potential.

How is the hero’s journey connected to self development?

You might be wondering what storytelling has to do with self-development. Before we dive into the hero’s journey (whether that is a male or a female hero’s journey), context will be useful. Joseph Cambell was heavily inspired by the work of Carl Jung, the groundbreaking psychologist who throughout his life worked on theories such as the shadow, collective unconscious, archetypes, and synchronicity.

Jung’s greatest insight was that the unconscious is a vast, vibrant landscape, yet out sight from the ordinary conscious experience. Jung didn’t only theorize about the unconscious; he provided a huge body of work explaining the language of the unconscious, and the way in which it communicates with the conscious mind.

The nature of the unconscious

Due to its vast nature, the unconscious doesn’t operate like the conscious mind, which is based in language, logic, and rationality. The unconscious instead operates in the imaginal realm — using symbols and meaning that take time to be deciphered and understood consciously. Such symbols surface in dreams, visualizations, daydreams, or fantasies.

For Jung, the creative process is one in which contents of the unconscious mind are brought to light. Enter storytelling and character development — a process of myth-making that somehow captures the truth of deep psychological processes.

Campbell saw the power of myth in igniting the unconscious will to grow and live a meaningful life. With that in mind, his structure offers a tool of transformation and a way to inspire the unconscious to work towards your own hero’s journey.

The 12 steps of the hero’s journey

The hero’s journey ends where it begins, back at the beginning after a quest of epic proportions. The 12 steps are separated into three acts:

- departure (1-5)

- initiation (5-10)

- return (10-1)

The hero journeys through the 12 steps in a clockwise fashion. As Campbell explains:

“The usual hero adventure begins with someone from whom something has been taken, or who feels there is something lacking in the normal experience available or permitted to the members of society. The person then takes off on a series of adventures beyond the ordinary, either to recover what has been lost or to discover some life-giving elixir. It’s usually a cycle, a coming and a returning.”

Let’s take a closer look at each of the steps below. Plus, under each is a psychological symbol that describes how the hero’s journey unfolds, and how when the hero ventures forth, he undergoes an inner process of awakening and transformation.

1. The ordinary world

The calm before the storm. The hero is living a standard, mundane life, going about their business unaware of the impending call to adventure. At this point, the hero is portrayed as very, very human. There could be glimpses of their potential, but these circumstances restrict the hero from fulfilling them. Although well within the hero’s comfort zone, at this stage, it’s clear something significant is lacking from their life.

Psychological symbol

This is represented as a stage of ignorance, pre-awakening. Living life by the status quo, on other people’s terms, or simply without questioning if this is what you want. At this point life is lived, but not deeply satisfying.

2. Call to adventure

Next is a disruption, a significant event that threatens the ways things were. This is a challenge that the hero knows deep down will lead to transformation and change, and that the days of normality, “the way things are,” are numbered. The hero confronts the question of being asked to step into their deeper potential, to awaken the power within, and to enter a new, special world.

Many of us embark on inner-journeys following hardship in life — the death of a loved one, the loss of a job, physical or mental illness. This stage occurs when it becomes apparent that, to move through suffering, one has to look within, to adventure into the soul.

3. Refusal of the call

No compelling story would be complete without friction. The hero often resists this call to adventure, as fear and self-doubt surface at full force, and the purpose of this new life direction is questioned. Can the reluctant hero journey forth? Do they have the courage?

The only way to grow and live a deeply fulfilling life is to face the discomfort of suffering. Campbell himself once said: “ The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek .” At this stage, fears, and anxieties about delving deep into the psyche arise. The temptation is to remain blissfully ignorant, to avoid discomfort, and to stay in your familiar world.

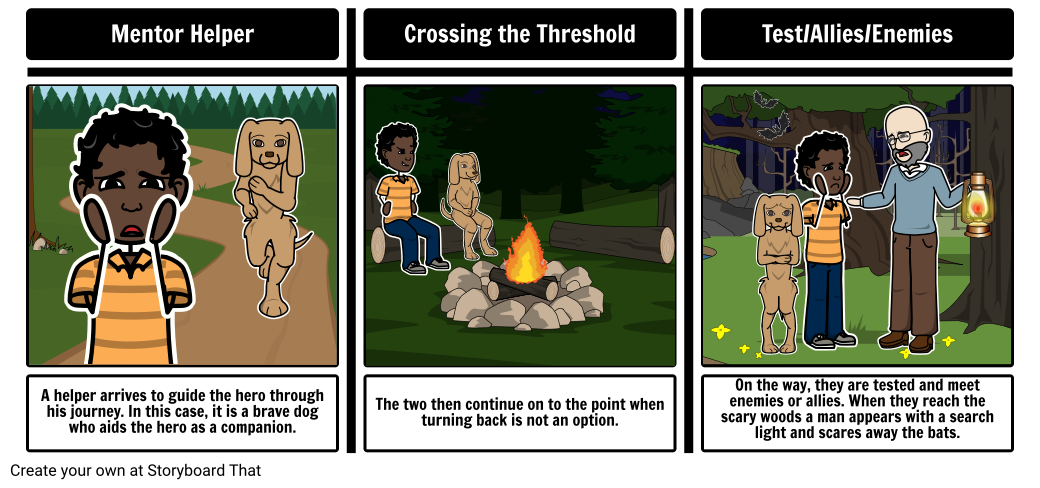

4. Meeting a mentor

As the hero faces a crisis of confidence, a wise mentor figure appears.

This character offers inspiration, guidance, or understanding that encourages the hero to have the self-belief to start this new adventure. In many stories, a mentor is someone else who has embarked on the hero’s journey, or someone who attempted, and failed. This person reflects the importance of this mission, reminding the hero their calling far exceeds their fear.

When the journey of exploration has to begin, people or situations enter your life at just the right time, guiding you in the right direction. This could be a close friend, a peer, a professional, such as a coach or therapist, or even a fictional character in a film or book. In most cases, these are chance encounters that contain a sense of knowing before the hero leaves on his or her adventure.

5. Crossing the threshold

This is a pivotal moment in the hero’s journey, as the initiation begins. This occurs when the hero fully commits to their quest, whether physical, emotional, or spiritual. This is the point of no return, where the reluctant hero embarks on their adventure, and has accepted that the way things were must change. The hero enters a new zone, one in which the call to adventure must be accepted. The hero’s resolve is hardened, and they understand they have a responsibility to confront what is ahead of them.

Whatever your life was before the call to action, this is a crossroads which is accepted, knowing your life may never be the same. This is a point of empowerment, where you realize that journeying within will lead you to greater self-understanding, even if those insights will dramatically change your life direction.

6. Test, allies, enemies

Now the hero has ventured outside of their comfort zone, the true test begins. This is a stage of acclimatizing to unknown lands. Unknown forces work against them, as they form bonds with allies who join them along the way, or face formidable enemies or encounters that have to be conquered. Throughout this testing time, the hero will be shaped and molded through adversity, finding deeper meaning in their life and mission.

Once the journey of self-discovery is underway, the initial burst of inspiration might be tested by the difficulty of the task. You might meet people who are able to offer advice or guide you, or those who reflect areas of yourself you have to work on.

Often, these are inner experiences, in the forms of memories, emotions, or outward tests, such as difficult circumstances that challenge your resolve and commitment to your new life direction.

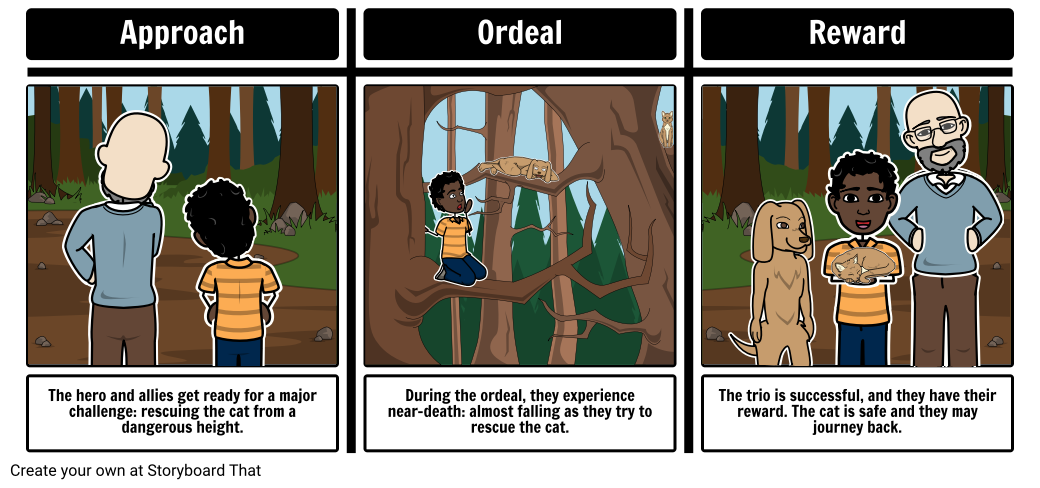

7. Approach to the inmost cave

Having already crossed the threshold into the unknown and the uncertain, having faced obstacles and enemies, and having begun to utilize their qualities along the way, the next stage is another threshold.

This is the beating heart of the hero’s challenge, where again self-doubt and fear can arise, as another threshold has to be crossed. This is often a period of respite, giving the hero time to pause and reflect. Will the hero make the leap?

The hero’s journey has ups and downs. There may be quick wins in the beginning — your new life direction may go well, or inner-work may lead you to a new place of calm or confidence. But then, out of nowhere, comes an even bigger challenge, surfacing as a question mark to the person you’ve become. Life often has a way of presenting the right challenges at the right time…

This is the life-or-death moment. This can be a meeting with an ultimate enemy or facing the hero’s deepest fear. There is an awareness that if the hero fails, their new world, or their life, could be destroyed.

Everything the hero has fought for up to this point, all the lessons learned along the journey, all the hidden potentials actualized, will have to be utilized to survive this supreme ordeal, for the hero to be victorious. Either way, the hero will undergo a form of death, and leave the ordeal forever changed.

There are inner challenges that have to be confronted on the journey of self-discovery. This might be in the form of trauma that has to be confronted and healed, people with whom you have to have difficult conversations, or fears you have to face, actions that in the past you never thought you’d be capable of. But, with the skills you’ve learned along the way, this time you’ll be ready. But it won’t be easy.

9. Reward (seizing the sword)

Through great adversity comes triumph. Having confronted their greatest fear, and survived annihilation, the hero learns a valuable lesson, and is now fully transformed and reborn — with a prize as a reward.

This object is often symbolized as a treasure, a token, secret knowledge, or reconciliation, such as the return of an old friend or lover. This prize can assist in the return to the ordinary world — but there are still a few steps to come.

When confronting deep inner fears or challenges, you are rewarded with deep insights or breakthroughs. That might be in the form of achieving a significant goal or inwardly having a sense of peace or reconciliation with your past, or moments that have previously felt unresolved. As a spiritual process, this may also be the realization that behind suffering and pain lies freedom or inner peace.

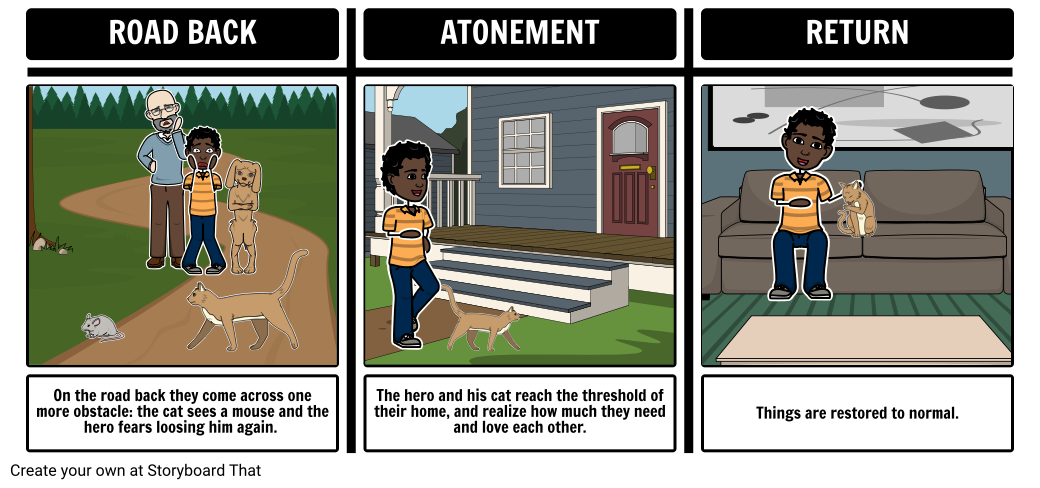

10. The road back

Having traveled into distant, foreign lands and slain the dragon, now it’s time for the hero to make their return journey. This stage mirrors the original call to adventure and represents another threshold.

The hero may be understanding their new responsibility and the consequences of their actions, and require a catalyst to make the journey back to the ordinary world with their prize.

The hard work has been done, the ultimate fear confronted, new knowledge found. Now, what’s the next step? For many, the initial stages of growth come with a period of renunciation or are symbolized by an outward journey away from home, or away from familiarity.

Then comes the stage of returning to familiarity, or the things left behind — be it family, friends, locations, or even behaviors that were once loved and sacrificed during the journey.

11. Resurrection

When it appears the hero is out of the woods, there comes a final confrontation — an encounter with death itself. Transformed inwardly and with a personal victory complete, the hero faces a battle that transcends their individual quest, with its consequences far-reaching, for entire communities or even humanity itself.

This purification solidifies the hero’s rebirth, as their new identity fully emerges just in time to return to the ordinary world.

In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, self-actualization is secondary to self-transcendence. In other words, once inner battles have been faced, and the alchemy of psychological transformation is underway, the next stage is to apply the newfound insights and knowledge to a bigger cause — supporting others, or standing up a mission that will benefit the wider world.

12. Return with the elixir

Following the final battle, the hero finally returns home. By now, personal transformation is complete, they’re returning home a different person. Having faced indescribable hardship, the hero returns with added wisdom and maturity. The elixir is the treasure they’ve returned with, ready to share with the ordinary world. This could be a sense of hope, freedom, or even a new perspective to assist those originally left behind.

The hero has a new level of self-awareness, seeing the ordinary world through fresh eyes. They’ve left internal conflict behind. There’s an understanding that things will never be the same, but that the hero’s journey was part of their destiny.

Then comes the ultimate prize: a final reconciliation, acceptance from the community, celebration, redemption. Whatever the prize, there are three elements: change , success , and proof of the journey .

Following a transformative psychic process, there’s an understanding of what is within your control. The “ordinary world” may have many elements that remain the same, but this is accompanied by a realization that when you change, so does your reality. Previously modes of thinking may be replaced, as bridges are built with your past, giving opportunity for a renewed approach to life.

What can we learn from the hero's journey?

At the time of writing this article, I’m in the UK visiting my family for the first time in 18 months. As I walked down paths I’d walked throughout my childhood, I was struck by how much I’ve changed over the years. A passage from T.S Eliot’s poem Little Gidding came to mind:

“We shall not cease from exploration. And the end of all our exploring. Will be to arrive where we started. And know the place for the first time.”

I reflected on the notion of coming full circle — to begin a journey, outwardly or inwardly, before finding yourself back at the beginning, transformed. In spiritual traditions, the circle is a powerful symbol of timelessness, death and rebirth, totality, and wholeness. Aptly, the 12 steps of the hero’s journey are depicted as a circle. It’s not a coincidence.

What can we learn from the hero’s journey? In a way, it is similar to the writer’s journey. Above all else, it’s a reminder that we each within us have a purpose, a quest and a mission in this life that can and will invoke our truest potential. The path isn’t easy — there are many, many challenges along the way. But at the right time, people and situations will come to our aid.

If you’re able to confront the mission head-on and take bold steps along the way — just like all the heroes of fiction before you, from Shakespeare’s characters to Luke Skywalker and Rey from the universe brought to us by George Lucas — then you will be transformed, and then you can return to where you started, reborn, ready to share your gifts and your lessons with the world.

Hot Stories

Couple marries 10 years after interracial marriage becomes legal — now they’re goals, usps worker goes 400 extra miles to make a special delivery - 8 decades in the making, not everyone has a great relationship with their mom — and that's ok, man continues sending ex-wife anniversary cards - 22 years following divorce, jennifer garner's mom made only $1 a day - but she was determined to change her family’s fate, man tries to scam 84-year-old out of $8,000 - she outsmarts him with a clever question, man spending his birthday all alone calls 911 - he didn't think cops would show up.

Cops Surprise Lonely Man Who Called 911 on His Birthday

Most of us know that if you’re ever in an emergency situation, you can call 911 for immediate help. Well for one man, having no one there to help him celebrate his birthday was an emergency. So he called the help line just to hear some well wishes. What he didn't expect was for two police officers to show up.

Making the Call

White and pink covered cake with lightened candle

According to WHDH News in Boston, a local man called 911 on May 2, just after midnight. It was his birthday, and he just wanted someone to wish him a happy birthday.

Initially, the responders thought the call was a joke. Officer Israel Bracho told the outlet he and his partner believed the man was pulling their leg, but then they verified he was telling the truth.

Different states have different penalties for misusing the emergency line. But this time, the police officers took another approach and decided to make the man's day memorable.

“Everyone has one birthday, so everyone deserves to feel special on that day,” Bracho said.

A Big Surprise

On their way to see the man, Chris, Bracho and his partner made a stop to pick up a muffin and candles.

“On our way there, we decided we can’t show up to someone’s house empty-handed. My mother raised me right — she would’ve killed me if I didn’t,” Bracho explained.

The pair showed up just before 1 a.m. with the treat. In the bodycam footage , which was later shared on social media , Chris’ face lit up when he realized the officers were there to celebrate him.

“Oh my God,” he said as the officers sang “Happy Birthday.”

“You guys are awesome,” the now 25-year-old said. “This is more than I could ask for.”

“Don’t eat it all in one sitting,” Bracho joked. “Take it easy, brother; God bless you.”

Spreading Kindness

It’s always heartwarming to hear stories of police officers taking to their communities and spreading kindness like the officers in this story did. We often hear about bad or scary situations, so moments like these are a great reminder that police are there to serve the community in various ways.

This story also reminds us that sometimes it’s easy to be kind and help someone when they need it most. Not everyone has someone to spend a birthday or special occasion with, but by taking the time to remember them — even with a small token — you can make a huge difference in their day.

Everyone deserves to feel special once in a while, and that’s within all of our power to do. All it takes is a smile, a kind gesture, or some nice words to turn another person’s day around. And in a pinch, a muffin will do.

Teen Is Incarcerated for Helping Drug Gang - Years Later, She Passes the Bar Exam on First Try

Mom leaves kids after husband's death - so her 10-year-old son takes charge, dying woman has one last wish - and her "young boyfriend" fulfills it, grieving starbucks barista serves a stranger - minutes later, she returns with a note, lamar odom regrets choosing khloe kardashian over taraji p henson, the kardashian redemption - an uncensored documentary, how did betrayal connect jennifer aniston and selena gomez, how tiffany haddish finally found the love she deserved, subscribe to our newsletter, the great takedown of nickelodeon’s dan schneider - how even small voices have the power for impact, chris gardner beyond the pursuit of happyness: the work begins, 100 powerful motivational quotes to help you rise above, wim hof: the iceman’s heroic journey to warming the hearts of millions, plus-size plane passenger refuses to give up extra seat to toddler - strangers "weigh in".

Plus-size Passenger Refuses to Give Up Extra Seat To Toddler

Flying may be the quickest way to travel but it isn't always the most comfortable. The seats are small, legroom is almost non-existent, and there's always that one annoying passenger in front of you who seems to find extreme enjoyment in testing the limits of just how far back that reclining seat can go.

Airlines are notorious for cramming in as many people as possible in the smallest spaces possible, which can be especially difficult for plus-sized passengers.

One woman decided to combat this by purchasing an extra seat.

But instead of sitting back and enjoying her flight, she found herself at the center of attention after refusing to give up the extra seat she had rightfully paid for to accommodate a toddler on the crowded flight.

Obese Woman Refuses to Give Up Extra Seat

Taking to the Reddit forum, Am I The A**hole , a 34-year-old woman explains that she is "actively working toward losing weight" but is still obese.

After having a bad experience on a previous flight, she opted to book an additional seat.

"...because I’m fat, I booked an extra seat so everyone can be more comfortable. I know it sucks having to pay for an extra seat but it is what it is."

At first, everything goes smoothly. She checks in, makes it through security, and boards the plane.

But just as she is settling into her seat, her trip takes a nosedive.

"This woman comes to my row with a boy who appeared to be about a year old," she writes. "She told me to squeeze in to one seat so her son could sit in the other."

Not only does the mother disparagingly tell her to "squeeze in" but she doesn't even bother to ASK her to move, she TELLS her to.

Understandably, the woman refuses to budge. "I told her no and that I paid for this seat for the extra space," she writes.

Despite the fact that the woman has every right to deny the order, and she has the ticket to prove it, the mother digs in. Her "huge fuss" attracts the attention of a nearby flight attendant.

"She told the flight attendant I was stealing the seat from her son, then I showed my boarding passes, proving that I, in fact paid for the extra seat."

And here's where things really take off. The flight attendant sides with the mother and asks the plus-sized passenger if she "could try to squeeze in."

She again refuses. "The boy, who the mom said is 18 months old was supposed to sit in her lap so he could do just that," she explains.

Eventually, the flight attendant tells the mom to put her son on her lap.

But the flight is already ruined. The Redditor shares that the unhappy mom wouldn't let it go, giving her dirty looks and passive-aggressive remarks for the entire flight.

She ends her post begging the question, "I do feel a little bad because the boy looked hard to control so AITA?"

The Internet Weighs In

The plus-sized woman's refusal to give in to the mom's demand has sparked a whole lot of feelings. The post has gone viral on Reddit with over 18,000 upvotes and nearly 5,000 commenters "weighing in."

The comments are overwhelmingly in support of the OP (original poster). In fact, you'd be hard-pressed to find a comment that supported the "entitled mother."

"She’s TA for not buying a seat for her son and assuming someone else would give up a seat they paid for. Odds are she was hoping there’d be extra seats on the flight so she didn’t have to pay and used the lap thing as a loophole."

"NTA. Look, at the base level, you paid for the seat regardless of the reason. You're entitled to use it, not the mom with a wriggly toddler. Not your kid, not your problem."

Commenters praised the OP for selflessly dishing out for an extra seat to accommodate her size in an attempt to make others flight comfortable too.

"NTA, and I hope it doesn't sound condescending to say, but good for you buying the extra seat. You being the sort of conscientious person who will spend the extra money to avoid encroaching on others is probably why you are having (needless) self-doubt about the encounter. The mom was entitled and fully in the wrong, and if the flight attendant gave you attitude then they are in the wrong, too."

And this brings up a valid point about the flight attendant's response. Should she have tried to force the issue?

"What's even the point of the extra seat if the flight attendants are going to let entitled people bully others into giving up the extra seat?"

"The cabin crew should have stopped this straight away once they saw you had booked both seats, it should have been obvious why. They should not have asked you to squeeze in to 1 seat."

Standing Up For Your Rights

While it is possible to have empathy and compassion for the mother (flying with little ones is challenging at best) she did, essentially, try to commandeer a stranger's seat.

A seat she had no right to and didn't pay for. Now there's no telling if she tried to purchase a seat for her toddler and there were no more tickets available or if she was banking on a stranger to accommodate her child.

Either way, the plus-size woman specifically paid for an extra seat so she wouldn't have to deal with the uncomfortable and frankly dehumanizing experience of trying to "squeeze in" to a seat made for bodies that conform to ridiculously narrow societal standards.

While it can be difficult to stand up for your rights in the face of opposition, it is important to advocate for yourself.

What do you think? Did she do the right thing?

*Featured image contains photos by George Zografidis and Gustavo Fring

Copyright © 2024 Goalcast

Get stories worth sharing delivered to your inbox

TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Sep 07, 2022

Dan Harmon Story Circle: The 8-Step Storytelling Shortcut

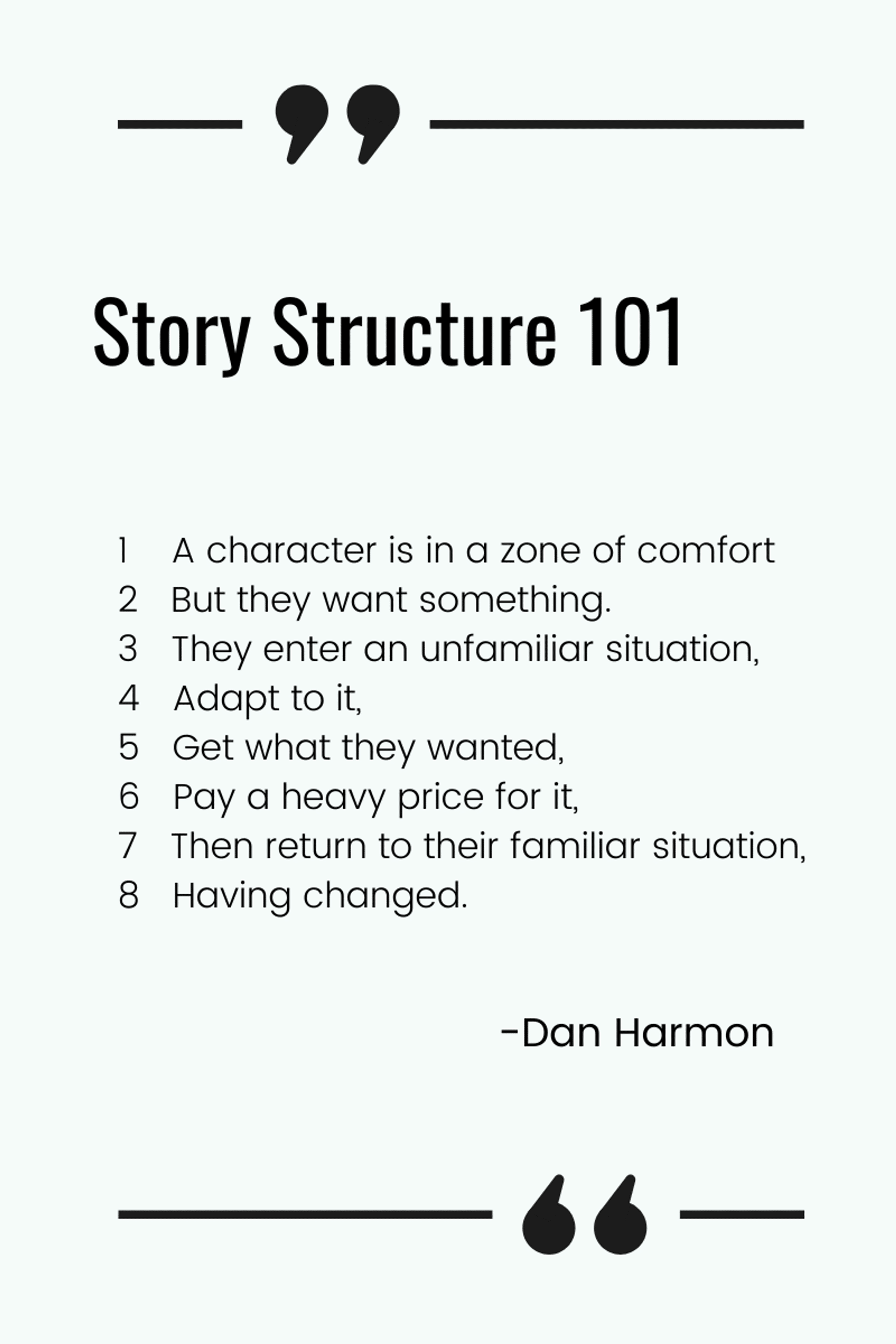

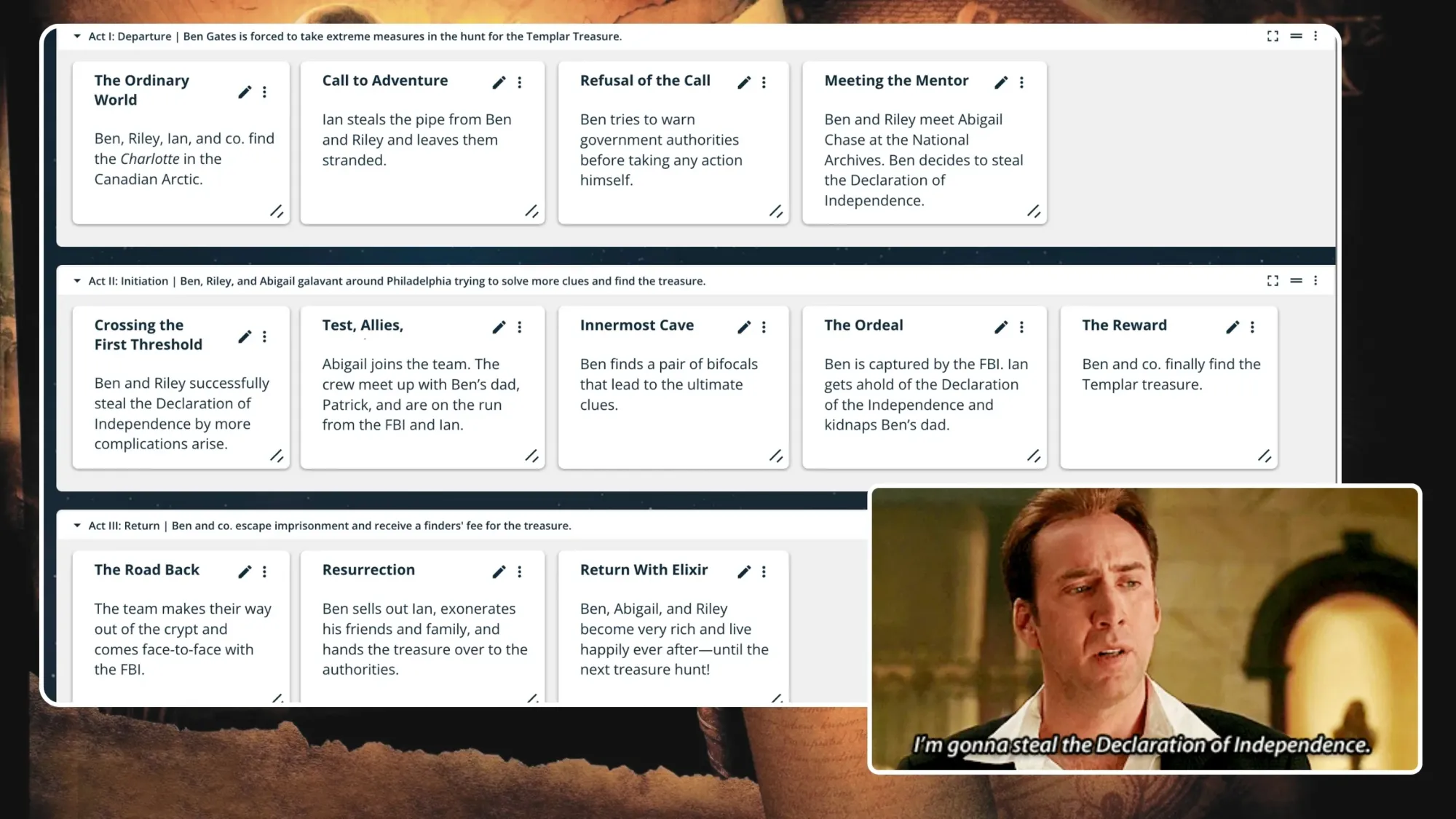

The Dan Harmon Story Circle, also known as “The Embryo”, is an approach to plotting developed by TV writer Dan Harmon. It follows a protagonist through eight stages, beginning with the character being in their comfort zone, then venturing out into the unknown to seek something they want. The character achieves their desire, but at a great cost, and ultimately returns transformed by what they’ve experienced.

This narrative framework is applicable to a wide range of genres and forms, and is a great way to structure any story that focuses on character development. This post contains a breakdown of the individual steps, gives examples of the Story Circle in action, and explains why it’s such an invaluable template for writers.

What is the Dan Harmon Story Circle?

This particular story structure is adapted from The Hero’s Journey — which itself derives from the work of academic Joseph Campbell. The Story Circle lays out a kind of narrative arc that's commonly used by myths from all over the world and emphasises how almost all forms of storytelling have a cyclical nature. In broad strokes, they always involve:

- Characters venturing out to get what they need, and

- Returning, having changed.

The Story Circle functions similarly — so, you may ask, why not just use the original? In short, Campbell’s system is more complex (11-steps), and alludes to a particular type of story, namely high fantasy (think knights, wizards, potions, and swords in stones). What Harmon did was streamline this process to just eight steps, and broaden them out to be less genre specific. The benefit of Harmon’s version over Vogler’s is that it focuses more specifically on character and is much easier to apply to a wider range of stories.

You might be asking why Harmon doesn’t just lay this structure out in a flat line. When asked about this, he points to the rhythms of biology, psychology, and culture as his inspiration: how we all move cyclically through phases of life and death, conscious and unconscious, order and chaos.

The fascinating thing he points out is that cycles like these are, in part, what have allowed humans to evolve .

“Behind (and beneath) your culture creating forebrain, there is an older, simpler monkey brain with a lot less to say and a much louder voice. One of the few things it's telling you, over and over again, is that you need to go search, find, take and return with change. Why? Because that is how the human animal has kept from going extinct, it's how human societies keep from collapsing and how you keep from walking into McDonald's with a machine gun.”

“We need [to] search — We need [to] get fire, we need [to find a] good woman, we need [to] land [on the] moon — but most importantly, we need RETURN and we need CHANGE, because we are a community, and if our heroes just climbed beanstalks and never came down, we wouldn't have survived our first ice age.”

What Harmon's getting at is that stories are a basic, universal part of human culture because of their millennia-long history as both a teaching and a learning tool. This idea of questing, changing, and returning is not a hack concept concocted by lazy writers, but an ingrained part of our collective psyche. That’s why stories from one culture are able to resonate with people across the world.

In Harmon’s philosophy, when a book, film, show, or song doesn’t meet the criteria above, it’s not necessarily bad writing: it’s simply not a story.

The 8 steps of Dan Harmon’s Story Circle

Now that we’ve got the background, it’s time to get into the meat: what are the steps of the Story Circle, and what do they entail.

Here are the Story Circle’s 8 steps:

- A character is in a zone of comfort. Everyday life is mundane and unchallenging.

- But they want something. The protagonist’s desire compels them to take action.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation. The character crosses the threshold to pursue what they want.

- Adapt to it. They acquire skills and learn how to survive in this new world.

- Get what they wanted. The character achieves their goal, but at a cost.

- Pay a heavy price for it. New and unexpected losses follow the victory.

- Then return to their familiar situation. The character goes back to where they started.

- Having changed. The story’s resolution; the lessons they’ve learned stay with them, and the character has grown.

In the video below, Harmon applies the story circle to an episode of Rick and Morty entitled “Mortynight Run.” For enough context to understand the clip, here’s some background info:

Rick is a mad, drunk, egomaniacal scientist who has invented a portal gun that allows him to have debauched adventures across time and space. He almost always drags his sensitive, anxious grandson Morty along for the ride. In this episode, they also bring along Morty’s father, Jerry, for whom Rick only has disdain.

Let's take another look at how the episode’s “A” story — which centers on Morty's journey — fits into the story circle.

1. A character is in a zone of comfort

The first beat of the story sees Rick and Morty on what seems like just another one of their adventures, flying through space with Jerry in tow. Things take a turn when Rick takes a call to organize a shady deal, and unceremoniously dumps Jeff from their spaceship.

It becomes apparent that Rick is carrying out an arms deal, selling weapons to an assassin to pay for an afternoon at the arcade — much to Morty’s dismay.

2. But they want something

As Harmon points out, “This is an ethical quandary for Morty.” The boy is put in a situation of guilt that compels him to “go across a threshold and search for a way to undo the ethical damage that he perceives Rick as doing.” Putting things right is Morty’s “want”, which takes us to the next stage.

3. They enter an unfamiliar situation

Even though he rarely defies his grandfather’s instructions, Morty takes Rick’s car keys and chases after the assassin, accidentally killing him in the process. He’s now trapped in an Intergalactic Federation outpost.

4. Adapt to it

Morty discovers an alien gas entity named ‘Fart’ — who was the assassin’s target. Going against Rick’s instructions once more (and making what he believes to be the ethical choice), Morty liberates Fart from space jail and they make their escape.

5. Get what they wanted

Morty has achieved his goal: he’s saved a life, and stopped a prolific assassin — and can now rest assured that he’s done the right thing.

6. Pay a heavy price for it

“In the second half of the story, we start finding out that the act of saving that life is going to cost a lot of other people their lives,” Harmon explains. Bounty hunters and law enforcement are seeking the group, and Fart slaughters many space cops and innocent bystanders while Rick and Morty make their escape.

7. Then return to their familiar situation

After the escape, the gang returns to a place resembling ‘normal life’, a phase Harmon refers to as “crossing the threshold” (here metaphorical, rather than a literal return home). At this point, Morty realizes that Fart is a truly malevolent creature and means to return with his people to destroy all carbon-based life.

Note: On the Circle diagram, Step 7 (the return) is directly opposite to Step 3, where Morty first crossed the threshold into the unfamiliar situation. Balance and harmony are a big part of Harmon's approach to storytelling.

8. Having changed

“So Morty makes the decision to change into someone who kills.” Realizing that his belief that all lives must be saved is not an absolute truth — some are simply malevolent — he terminates Fart, thereby saving the universe and becoming someone different from the person he started as. As Harmon points out, this is not a show for kids: not all protagonists need to learn universally positive messages for a story to ring true.

Harmon has laid out his process for using the story circle in a fascinating set of posts (warning: contains swears) where he also talks about the nature of storytelling, answering questions like…

Why use the Story Circle?

According to Harmon, the beauty of the Story Circle is that it can be applied to any type of story — and, conversely, be used to build any type of story, too.

“Start thinking of as many of your favorite movies as you can, and see if they apply to this pattern. Now think of your favorite party anecdotes, your most vivid dreams, fairy tales, and listen to a popular song (the music, not necessarily the lyrics).”

So let’s put that theory to the test. Let’s pick an example that’s far removed from Harmon’s own work see if it applies: Dickens’s Great Expectations .

- Zone of Comfort : Pip, a young orphan, lives a modest life on the moors.

- But they want something : He becomes obsessed with Estella, a wealthy girl of his age.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation : A mysterious benefactor plucks Pip from obscurity and throws him — a fish out of water — into London society.

- Adapt to it : He learns to live the high life and spends his money frivolously

- Get what they wanted : Pip is finally a gentleman, which he believes will entitle him/make him worthy of Estella.

- Pay a heavy price for it : Pip discovers that his money came from a convict, he drowns in debt, he regrets alienating his Uncle, he realizes that his pursuit of Estella is futile.

- Then return to their familiar situation : Pip makes peace with his Uncle Joe (who nurses him back to health). Pip disappears to Egypt for years, and once again returns home…

- Changed : Back once again where the story started, a now-humbled Pip reunites with Estella who, due to some plot, is ready to open her heart to him.

Although Great Expectation was a serial, written week-by-week, Dickens must have consciously or unconsciously been aware of this cycle, or something like it. He sent his characters on a journey towards something they wanted — only for them to pay the price and return home, changed.

As with any sensible advice about structure, the takeaway here is not that you must slavishly adhere to a set formula or risk ruining your story. This story circle, along with other popular story structures like the three-act structure , are simply tools based on observations of stories that have managed to resonate with readers over the centuries. They can also be a great tool to know what should come next, and to pace yourself within your story — if you’re halfway through and still in the comfort zone, you know you need to make some changes.

There are, of course, plenty of other options for story structure, which you can learn about by reading the rest of this guide — or trying the quiz below!

Which story structure is right for you?

Take this quiz and we'll match your story to a structure in minutes!

Just know this: if you find yourself at an impasse with any story you’re writing — you could do a lot worse than crack out the story wheel, identify where you are, and see what comes next in the cycle.

3 responses

2deuces says:

25/07/2018 – 19:48

This is great. One difficulty about using the Hero's Journey and other Plot Structures is that the main character needs to end up in a different place than at the beginning. That is fine for a movie or a stand-alone book, book but what about episodic series such as Perry Mason, Poirot, or just about any TV series. The Story Circle solves this problem by bringing the MC (actually the entire cast) back to the beginning waiting for the next case, next mission, next customer to enter the bar etc. Even if the series has a long arc (Breaking Bad) over time we see Walter slowly evolving due to the impact of each episode.

↪️ Martin Pitt replied:

26/07/2018 – 20:33

The location does not need to differ, the change here explained was to the character themselves. After all with the given example, Morty usually always ends up back home. Whether they realised some truth, became more humble, or worse; On that note: If the character is worse off that could be fixed in a future story or you could have a really great villain on your hands to play with! Regardless, change could be anything I think or to someone else.

↪️ 2deuces replied:

27/07/2018 – 17:14

Sorry I didn't mean a different location but a different psychological place. Scrooge woke up in his bedroom but he was a different person on his return.

Comments are currently closed.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your stories to life

Use our free writing app to finally write — and publish — that book!

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Holiday Savings

cui:common.components.upgradeModal.offerHeader_undefined

The hero's journey: a story structure as old as time, the hero's journey offers a powerful framework for creating quest-based stories emphasizing self-transformation..

Table of Contents

Holding out for a hero to take your story to the next level?

The Hero’s Journey might be just what you’ve been looking for. Created by Joseph Campbell, this narrative framework packs mythic storytelling into a series of steps across three acts, each representing a crucial phase in a character's transformative journey.

Challenge . Growth . Triumph .

Whether you're penning a novel, screenplay, or video game, The Hero’s Journey is a tried-and-tested blueprint for crafting epic stories that transcend time and culture. Let’s explore the steps together and kickstart your next masterpiece.

What is the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey is a famous template for storytelling, mapping a hero's adventurous quest through trials and tribulations to ultimate transformation.

What are the Origins of the Hero’s Journey?

The Hero’s Journey was invented by Campbell in his seminal 1949 work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces , where he introduces the concept of the "monomyth."

A comparative mythologist by trade, Campbell studied myths from cultures around the world and identified a common pattern in their narratives. He proposed that all mythic narratives are variations of a single, universal story, structured around a hero's adventure, trials, and eventual triumph.