tools4dev Practical tools for international development

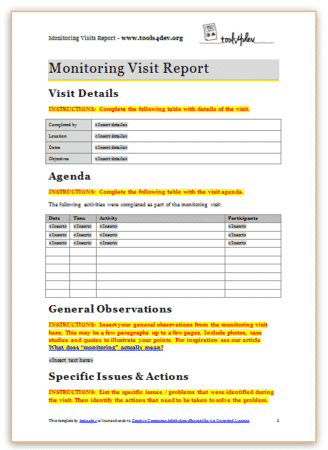

Monitoring visit report template

The purpose of a monitoring visit (sometimes called a supervision visit or a field visit) is to make sure that project activities are implemented the way they are described in the plan. It normally involves meeting with the people running the project, meeting with the participants, and observing the activities.

At the end of a monitoring visit, it is important to prepare a report that describes what you found. These reports will document any discrepancies between the plan and actual implementation, as well as improvements made by the project team.

This monitoring visit report template is appropriate when:

- You need to report the results of a monitoring visit, supervision visit, or field visit.

This monitoring visit report template is NOT appropriate when:

- Your organisation or donor already has a standard template for monitoring visit reports (in which case use their template).

Photo by U.S. Mission Uganda

Tags Monitoring & Evaluation

About Piroska Bisits Bullen

Related Articles

What can international development learn from tech start-ups?

13 May 2021

Social Enterprise Business Plan Template

12 May 2021

How to write an M&E framework – Free video tutorial & templates

10 September 2017

The Art and Science of Site Monitoring Visit Reports

An experienced CRA may follow all the rules and requirements for writing a site monitoring visit report (SMVR), but there are nuances that can make the difference between a report that simply follows that formula and one that really paints a picture its audience can understand.

Roslyn Hennessey, senior project manager at Westat describes the ideal SMVR as “a snapshot in time of what’s happening at the site.” To develop that snapshot, start by asking who will read the report, she advises. There are several types of audiences for SMVRs, all of which have slightly different interests:

- The sponsor wants to know about the performance of the site — is it in compliance with the protocol, are improvements needed, are there any major concerns;

- The PI and site staff want to know if additional training or procedural changes are needed;

- Regulatory authorities and auditors want to know if the site is in compliance and, if not, what corrective action was taken;

- Future monitors need enough information to ensure a smooth hand-off from one CRA to another.

It’s important to give all of the key stakeholders the “heart or the core of the information that they are most interested in,” she says.

And although an SMVR should be comprehensive, it also needs to be concise to avoid burying important information or tiring the reader. Writing an SMVR is an exercise in deciding what information needs to go in and what needs to stay out.

“We really need to get more efficient in terms of going just from point A to B,” she says, “but in that A to B, we need to include some important things.”

Hennessey recommends starting at the end. A monitor usually will have an overall message to convey in the report and should choose the information that supports that message. “Know what you want to say ahead of time and write to your conclusion,” she says. “What do I need to say to get me to that conclusion?”

Be analytical in what you write, she advises. A good SMVR is more than an “information dump.” When writing the report, provide the reader with some context instead of just transcribing notes. Explain what those notes indicate, Hennessey urges. Look for common denominators in the findings and identify root causes of problems. Pay attention to trends, from a single visit and across several visits.

In addition to being analytical, an SMVR should be objective. Elizabeth Weeks-Rowe, a clinical research training consultant, advises SMVR authors to keep the human factor in mind. A monitor may encounter many different personalities in a trial, but they should not be reflected in the site report.

“Taking the emotion out of verbiage is critical,” says Weeks-Rowe. “Be factual, not emotional.” If, for example, a principal investigator is less than professional, this impression should not be included in the report. Instead, address any outcome of that behavior. Making sure that all findings are actionable helps avoid an emotional narrative, she says.

Hennessey notes that an attentive monitor can enhance communication between the site and the sponsor. “Sometimes the investigators feel like the sponsor is too far removed,” she says, and wonder “where is my voice heard?” The investigator may feel more comfortable communicating with the CRA, who then passes the information on to the sponsor via the SMVR.

The last step in writing an effective SMVR is recommending corrective actions, Hennessey says. All issues/findings noted in the report should have an associated action and/or resolution. Have a “no finding left behind” policy, she advises. But, she cautions, don’t be overly prescriptive. It’s important that the PI and site staff take responsibility for problems and solutions.

Both Hennessey and Weeks-Rowe stress taking care of the basics, carefully reviewing the SMVR for misspellings and grammatical errors. Flaws in the presentation, Hennessey says, distract from the content and message and ultimately hurt the credibility of the monitor and the company.

Ultimately, the SMVR must be able to stand the test of time, Hennessey says. Trials can last for years and go through several CRAs along the way. “It’s not often that a CRA gets to work with a site from initiation to closeout,” she notes. And a regulatory request for further information or an audit can come at any time. In one case, she says, the FDA came back to question the SMVR 10 years after the fact.

Upcoming Events

Magi 2024: the clinical research conference, managing data and documentation for fda inspections and remote assessments, effective root cause analysis and capa investigations for drugs, devices and clinical trials, 2024 avoca quality consortium summit, featured products.

Surviving an FDA GCP Inspection: Resources for Investigators, Sponsors, CROs and IRBs

Best Practices for Clinical Trial Site Management

Featured stories.

Thought Leadership: Remote Patient Monitoring Gives New View of Safety in Cardiac Clinical Trials

Ask the Experts: Applying Quality by Design to Protocols

Clinical Trials Need Greater Representation of Obese Patients, Experts Say

FDA IT Modernization Plan Prioritizes Data-Sharing, AI, Collaboration and More

Standard operating procedures for risk-based monitoring of clinical trials, the information you need to adapt your monitoring plan to changing times..

Providing courses, products & services so Clinical Research Professionals can thrive & achieve fulfilling careers.

How to Plan a Productive Site Monitoring Visit

by ClinEssentials Team | Feb 28, 2022 | Tools for Research Professionals , Clinical Research Associates , Clinical Research Coordinators , Tips for Research Professionals | 0 comments

Many Clinical Research Associates are unprepared for their clinical trial monitoring visits, which is an important part of their role. It is understandable – CRAs are busy and it can be hard to find time for planning where there are so many other tasks to complete right away.

Monitoring visits are when CRAs ensure their studies are staying in compliance and on track. Creating a plan for the allotted time is the best way to ensure a productive, efficient monitoring visit.

What Happens at a Clinical Trial Monitoring Visit

Monitoring visits are typically very full days – jam-packed with all of the action items the CRA and the site need and want to accomplish.

A CRA may visit a site for site initiation, an Interim Monitoring Visit (IMV) – also called a Routine Monitoring Visit (RMV), or a study close-out. IMVs are the most common and usually happen every 4-6 weeks. However, monitoring plans differ and are determined by the Sponsor or CRO before a trial begins.

3 objectives of a monitoring visit

While there are many things that a CRA wants to successfully complete at a monitoring visit, there are three main objectives for each visit:

- Discover any data errors and/or discrepancies

- Evaluate the site staff’s understanding of the protocol and procedures

- Determine compliance

Standard tasks, meetings and goals of a monitoring check-in visit

Tasks are based on the reason for the visit. Since an Interim Monitoring Visit is the most common, here are the general business items that a CRA will address at a monitoring check-in visit:

- Review the regulatory binder, study documentation, and CRF entries

- Audit screening, enrollment, visit, and follow up data

- Conduct Source Data Verification

- Perform a safety assessment

- Examine the investigational product and study supplies

- Evaluate study personnel and site facilities

- Meet with the Principal Investigator and site staff

The Association of Clinical Research Professionals (ACRP) created this extensive checklist of tasks for a monitoring visit .

CRAs are responsible for documenting everything they observe, notice, and discuss during a visit. Following the visit, this information is compiled into a clinical monitoring report. Here are 5 guidelines for writing a useful clinical monitoring report from MasterControl.

Consequences of being Unprepared for a Monitoring Visit

Being prepared for a monitoring visit is instrumental in the success of the visit. When both the Clinical Research Associate and the research site are prepared, monitoring visits run smoothly and efficiently. The patient volunteers, clinical research team, and CRO or Sponsor are all negatively affected when the CRA or the site staff has not taken the time to prepare for a monitoring visit.

Scheduling conflicts and unavailability of key team members can lead to important meetings that have to wait until the next visit.

The site may not have the necessary documents or the regulatory binder ready for the CRA to review, which is one of the primary activities for most monitoring visits.

When monitoring visits are not successful and all essential tasks and meetings do not occur, the trial can be delayed – and potentially over budget. Sponsors and CROs may lose trust in the site and the staff.

3 Steps for a Successful Monitoring Visit

With proper communication and a simple 3 step process, preparing for a monitoring visit does not have to be overly time-consuming. Plus, spending time in advance will be time saved through an efficient, organized visit!

- Plan the visit. Download this free checklist that will lead to a well-planned visit. It even includes a list of documents to have on your computer and in your work bag. (The checklist can be modified based on the protocol or directions from the research team.)

- Review the study protocol and have a thorough understanding of the entire document.

- Bring clinical trial monitoring tools! Use the Visit To Do List to stay focused and on task. Provide the site staff with a copy of the Action Item List – and use the other copy to write the Monitoring Visit Report and Follow-Up Letter.

For more tips, check out Dan Sfera’s YouTube video about how CRAs should prepare for a site monitoring visit .

Stop showing up unprepared for a monitoring visit! As a leader and essential member of the research team, the site staff will appreciate and respect you for your thoroughness and organization – and this will be evident in their work!

For more great ideas and monitoring tools that help Clinical Research Professionals become more efficient, visit www.clinessentials.com .

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

More Resources

How to Get into Clinical Research

by ClinEssentials Team | Feb 7, 2024 | Clinical Research Careers , Clinical Research Coordinators , Clinical Trial Assistants , Tips for Research Professionals

How Clinical Trial Managers Are Involved with Study Recruitment

by ClinEssentials Team | Jan 10, 2024 | Clinical Research Careers , Clinical Trial Managers , Tips for Research Professionals

CRA Responsibilities for Each Stage of a Clinical Trial

by ClinEssentials Team | Dec 27, 2023 | Clinical Research Careers , Clinical Research Associates , Tips for Research Professionals

How to Review a Clinical Trial Protocol (Free Checklist Included)

by ClinEssentials Team | Nov 8, 2023 | Clinical Research Careers , Clinical Trial Managers , Tips for Research Professionals , Tools for Research Professionals

Site Monitor Visits

Study sites are monitored to ensure oversight of the clinical research study by the sponsor..

Regular site monitor visits can be broken down into four types: pre-study visits, initiation visits, periodic monitoring visits, and close-out visits. Study sites may also be monitored or audited by the FDA, Clinical Research Organizations (CROs), IRBs and sponsors. For more information on site audits by outside entities please visit the training documents on Quality Management: Audits .

Pre-Study Visits

Pre-study visits (site selection visits or site qualification visits (SQVs)) are conducted to determine if the investigator and clinical site have the capability to conduct the study. During this visit, both an investigator and a study coordinator must be available. When applicable, pharmacy staff may also need to be available. The monitor will usually request a tour of the facility and time to discuss the basic fundamentals of the protocol and how that relates to the feasibility of recruiting potential participants.

Other topics of discussion during the pre-study visit include:

- Investigator responsibilities

- Qualifications of investigator or other site personnel

- Study objectives, protocol-required procedures, eligibility criteria, and patient recruitment

- IRB (e.g., informed consent requirements)

- Adverse event reporting, source documentation, and record retention

- Space requirements, availability of a secure area to store investigations drug or devices, availability of required equipment

Initiation Visits

A Site Initiation Visit (SIV) is when the research study team receives adequate training from the sponsor or CRO on the protocol. It is also the opportunity for the sponsor or CRO to ensure that the investigator fully understands his/her responsibilities (21 CFR 312 Subpart D). This visit usually occurs after the site has completed all regulatory requirements and has obtained IRB approval for the research study at their site. The initiation visit is the last step before the study site is activated for enrollment by the sponsor.

During study start-up, a sponsor may choose to hold an investigator meeting for a large number of sites in lieu of conducting many site initiation visits. If you are required to travel to an investigator meeting for a study, visit the Office of Sponsored Programs (OSP) for OSU’s travel policies.

Other topics of discussion during the site initiation visit include:

- Study overview, eligibility criteria, procedures, access to suitable patient population

- Lab manual, requirements for research sample processing and shipping

- Regulations and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, informed consent requirements, IRB obligations, adverse event reporting, drug accountability

- Data forms review including Case Report Forms (CRFs)

- Regulatory documents and study file organization

- 21 CFR 312 Subpart D Responsibilities of Sponsors and Investigators

- OSP Travel

Periodic Monitoring Visits

The sponsor and/or CRO will develop a monitor plan that includes the frequency and duration of periodic monitor visits. The focus of these visits is to evaluate the way the study is being conducted and to perform source document verification. These visits can occur every few weeks to once a year and can take less than one day up to several days at a time. It is important to be familiar with the contract agreements, as they may contain the agreement as to the frequency and duration of site monitoring visits and the sponsor’s data entry expectations. The contract agreement should match what the sponsor and/or CRO creates in the site monitor plan.

At the beginning of the study, it should be determined where the monitor or monitors will work while they are on site. Ideally, the monitor should have their own workspace separate from the research study team. In addition, many monitors require internet access for their laptops. Instructions for OSUMC guest wireless can be found here .

Preparing for a periodic monitoring visit:

- Identify a quiet place for the monitor to work and ensure access to a copy machine, phone, water fountain, and restroom

- Complete all necessary CRFs

- Confirm that Serious Adverse Event (SAE) forms have been submitted and are available for review

- Obtain medical records for the CRFs to be reviewed

- Organize study file documents for review

- Confirm that signed consent forms for all enrolled participants are available

- Schedule an appointment for the monitor to visit the pharmacy if needed

- Schedule time for the study coordinator to meet with the monitor towards the end of the visit to review findings

- Schedule time for the investigator to meet with the monitor towards the end of the visit to review findings

Close-Out Visits

When the research study has been completed at a site, a close-out visit occurs. This type of visit can take the form of an on-site visit or, in some cases, be conducted via a telephone call. Some close-out visits are also combined with a final periodic monitoring visit.

Action items during the close-out visit may include:

- Discuss timelines and strategies for the completion of outstanding case report forms and queries

- Return or destruction of study drug

- Collect outstanding patient data forms and study forms such as the screening and monitoring logs

- Perform a final review of the study file documents

- Discuss the plans for record retention

- Discuss ongoing investigator responsibilities

Liu, M.B. and Davis, K.; Chapter 6: Monitoring. Lessons from a Horse Named Jim: a Clinical Trials Manual from the Duke Clinical Research Institute . Durham, NC: Duke Clinical Research Institute, 2001. Print.

If you have a disability and experience difficulty accessing this content, please submit an email to [email protected] for assistance.

GxP Lifeline

How to write a useful clinical monitoring report.

Documentation is among the least glamorous and most burdensome aspects of compliance . For regulators, nothing happened if it wasn’t documented. Some companies err on the side of caution by requiring too much documentation without focusing on the documentation’s purpose. However, it’s also important to not neglect documentation when it is needed. One place where this balance is particularly important is in site clinical monitoring .

Site monitoring reports serve a regulatory purpose by proving the site monitoring happened. Their usefulness extends beyond simply checking a box on the compliance checklist. A well-written report shouldn’t be an afterthought but should be an integral part of the site visit. The report and visit are essential parts of proper clinical trial management .

#1: Clinical Monitoring Report Preparation

Site monitoring has a purpose. Keep that purpose in mind as you prepare. There are requirements in the study protocol that must be met, some of which pertain to what information needs to be included in the report. Depending on how or if the clinical trial is using centralized or remote monitoring, some of the information for the report can be collected before the monitor is even on-site. If those methods are used, reviewing documentation and data can be done beforehand. Remote access to that information is also useful when it comes to writing the report after the visit.

An important component of preparing is to look at past clinical monitoring reports and audit reports, if any have been conducted. If a previous site interim visit reported a problem, that requires follow-up during the next visit. Time on-site is limited, so these issues should be prioritized. A risk-based approach to monitoring will also indicate certain areas that require precedent.

#2: Note Taking

Taking notes takes time, but it’s worth it in situations where you couldn’t possibly remember everything. The monitoring report template should be open throughout the visit, both to keep you on track and to give you a place to write notes. Everyone has their own system of taking notes, but your focus should be on the areas most important to regulators — patient safety and data quality. This is the whole reason for doing the site monitoring, so take notes that demonstrate adherence to protocol, good clinical practices (GCP) , and regulations. Or notes on how the site is not adhering to those requirements.

#3: Monitoring Follow-Up

Your clinical monitoring visit and the ensuing report aren’t isolated incidents. They will be shaped by previous visits and affect future ones. Hopefully, issues from the past site monitoring reports that you reviewed while preparing for the visit have been resolved. If not, include it in your notes and the final report. Any corrective action the site has implemented should prevent recurrence. The site and monitor should work together to find solutions that will bring the site into compliance. Your report should also include any items that will need follow-up during the next visit.

Besides follow-up for a single site, monitors should also be aware of how any issues might reflect a trend across the whole study. If multiple sites are having the same issue, it might have more to do with the study protocol than the sites themselves.

#4: Write Your Clinical Monitoring Report ASAP

Taking great notes is critical, but the best time to write the report is when it’s fresh on your mind. There might be details that didn’t make it into your notes that would soon be forgotten. Or you might look back at your notes later and realize something that made sense in the moment no longer does. It’s important to write the report quickly because human memory is fallible. Going along with that, if multiple site visits are scheduled for the same day, there’s danger in remembering something from one site as pertaining to another. At the very least, the report for one site should be written before visiting the next.

#5: Be Clear and Concise in Your Report

A site monitoring report shouldn’t read like a doctoral thesis. But it also can’t be a collection of bullet points. There’s a balance that monitors have to achieve between having too much information and not enough. The report absolutely should include:

- The date of the visit.

- Name of people involved (from the site and sponsor).

- Summary of what was reviewed.

- Description of any issues or potential issues (e.g., nonconformance, problems with data, etc.)

- Description of any corrective action, who is responsible for that action, and when that action will be completed.

While there’s no wordcount requirement for a site monitoring report, the summary and descriptions do need to be detailed enough to verify the monitoring plan was followed.

Documenting what happens during a clinical monitoring visit is just as important as the visit itself. It’s essential for showing the site is compliant with regulations and the study protocol. It also demonstrates the improvements sites make when issues are discovered and who is responsible for them. Reports from previous visits serve as a starting point for the next visit and ensure follow-up items aren’t forgotten. Keeping all this in mind, the site monitoring report needs to be given forethought and attention to make it a useful document.

Sarah Beale is a content marketing specialist at MasterControl in Salt Lake City, where she writes white papers, web pages, and is a frequent contributor to the company’s blog, GxP Lifeline. Beale has been writing about the life sciences and health care for over five years. Prior to joining MasterControl she worked for a nutraceutical company in Salt Lake City and before that she worked for a third-party health care administrator in Chicago. She has a bachelor’s degree in English from Brigham Young University and a master’s degree in business administration from DeVry University.

View {title}

- to the content

- to the main navigation

- to the service navigation

Monitoring Site Initiation Visit (SIV) Report Template

Carefully assessing whether a site is ready to start a trial is a crucial step towards mitigating risks when conducting a trial. This template includes a step-by-step checklist for monitors and covers all the important aspects of a site initiation visit (SIV). It complements our series of monitoring templates covering all aspects of monitoring from the starting line to the finish line. These templates are freely accessible and are suitable for all sites doing clinical research.

Is your site ready to start a trial?

The up-to-date and user-friendly Monitoring Site Initiation Visit (SIV) Report Template can be used to report a site initiation visit.

This template is a step-by-step checklist with convenient drop-down lists. It guides monitors through all the important aspects of a site initiation visit (SIV), so they can assess whether a site is ready to start a clinical trial. It is part of a series of monitoring templates that includes:

- Monitoring Close-Out Visit (COV) Template

- Monitoring Visit Report Template

- Monitoring Plan Template

- Routine Monitoring Visit and Close-Out Visit (RMV-COV) Report Template

This template is suitable for any monitor engaged in clinical research in Switzerland and abroad. We particularly recommend using this template within the SCTO’s CTU Network for investigator-initiated, multicentre studies. It can also be used as a self-assessment form for study sites in anticipation of a site initiation visit.

This template was developed by the SCTO’s Monitoring Platform and first published in August 2021 and last revised in March 2023 (V3).

Monitoring Site Initiation Visit Report, cover page

Monitoring Site INitiation Visit Report, page 1

Monitoring Site Initiation Visit Report, page 2

Monitoring Site Initiation Visit Report, page 3

Monitoring Site Initiation Visit Report, page 4

Monitoring Site Initiation Visit Report, page 5

Monitoring Site Initiation Visit Report, page 6

This template is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0. Its content can be shared and adapted as long as you follow the terms of the license. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

- Monitoring Site Initiation Visit Report V3 (last revised in March 2023) (docx, 1.28 MB)

Our templates and tools are free. As a publicly funded organisation, we strive to inform the public about the impact of our work and to continually improve our services. We therefore kindly ask you to leave us your email address so we can contact you with a short one-time survey. You may download the document without providing your personal data.

Questions or suggestions?

Feel free to contact us with any questions or feedback related to this resource!

Before continuing on our website: We use cookies on our website to ensure that it functions smoothly and to analyse website use. Please read our data privacy statement and accept the use of cookies.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Sage Choice

Triggered or routine site monitoring visits for randomised controlled trials: results of TEMPER, a prospective, matched-pair study

Associated data.

Supplemental material, 793379_supp_mat for Triggered or routine site monitoring visits for randomised controlled trials: results of TEMPER, a prospective, matched-pair study by Sally P Stenning, William J Cragg, Nicola Joffe, Carlos Diaz-Montana, Rahela Choudhury, Matthew R Sydes and Sarah Meredith in Clinical Trials

Supplemental material, 793379_supp_mat_2 for Triggered or routine site monitoring visits for randomised controlled trials: results of TEMPER, a prospective, matched-pair study by Sally P Stenning, William J Cragg, Nicola Joffe, Carlos Diaz-Montana, Rahela Choudhury, Matthew R Sydes and Sarah Meredith in Clinical Trials

Supplemental material, 793379_supp_mat_3 for Triggered or routine site monitoring visits for randomised controlled trials: results of TEMPER, a prospective, matched-pair study by Sally P Stenning, William J Cragg, Nicola Joffe, Carlos Diaz-Montana, Rahela Choudhury, Matthew R Sydes and Sarah Meredith in Clinical Trials

Supplemental material, 793379_supp_mat_4 for Triggered or routine site monitoring visits for randomised controlled trials: results of TEMPER, a prospective, matched-pair study by Sally P Stenning, William J Cragg, Nicola Joffe, Carlos Diaz-Montana, Rahela Choudhury, Matthew R Sydes and Sarah Meredith in Clinical Trials

Supplemental material, 793379_supp_mat_5 for Triggered or routine site monitoring visits for randomised controlled trials: results of TEMPER, a prospective, matched-pair study by Sally P Stenning, William J Cragg, Nicola Joffe, Carlos Diaz-Montana, Rahela Choudhury, Matthew R Sydes and Sarah Meredith in Clinical Trials

Background/aims

In multi-site clinical trials, where trial data and conduct are scrutinised centrally with pre-specified triggers for visits to sites, targeted monitoring may be an efficient way to prioritise on-site monitoring. This approach is widely used in academic trials, but has never been formally evaluated.

TEMPER assessed the ability of targeted monitoring, as used in three ongoing phase III randomised multi-site oncology trials, to distinguish sites at which higher and lower rates of protocol and/or Good Clinical Practice violations would be found during site visits. Using a prospective, matched-pair design, sites that had been prioritised for visits after having activated ‘triggers’ were matched with a control (‘untriggered’) site, which would not usually have been visited at that time. The paired sites were visited within 4 weeks of each other, and visit findings are recorded and categorised according to the seriousness of the deviation. The primary outcome measure was the proportion of sites with ≥1 ‘Major’ or ‘Critical’ finding not previously identified centrally. The study was powered to detect an absolute difference of ≥30% between triggered and untriggered visits. A sensitivity analysis, recommended by the study’s blinded endpoint review committee, excluded findings related to re-consent. Additional analyses assessed the prognostic value of individual triggers and data from pre-visit questionnaires completed by site and trials unit staff.

In total, 42 matched pairs of visits took place between 2013 and 2016. In the primary analysis, 88.1% of triggered visits had ≥1 new Major/Critical finding, compared to 81.0% of untriggered visits, an absolute difference of 7.1% (95% confidence interval −8.3%, +22.5%; p = 0.365). When re-consent findings were excluded, these figures reduced to 85.7% versus 59.5%, (difference = 26.2%, 95% confidence interval 8.0%, 44.4%; p = 0.007). Individual triggers had modest prognostic value but knowledge of the trial-related activities carried out by site staff may be useful.

Triggered monitoring approaches, as used in these trials, were not sufficiently discriminatory. The rate of Major and Critical findings was higher than anticipated, but the majority related to consent and re-consent with no indication of systemic problems that would impact trial-wide safety issues or integrity of the results in any of the three trials. Sensitivity analyses suggest triggered monitoring may be of potential use, but needs improvement and investigation of further central monitoring triggers is warranted. TEMPER highlights the need to question and evaluate methods in trial conduct, and should inform further developments in this area.

Introduction

Clinical trial monitoring is defined by the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) as ‘The act of overseeing the progress of a clinical trial, and ensuring that it is conducted, recorded and reported in accordance with the protocol, Standard Operating Procedures, Good Clinical Practice (GCP), and the applicable regulatory requirements’, and aims to protect the rights and well-being of trial participants, while ensuring protocol compliance and data integrity. 1

Monitoring often relies on-site visits, an approach recommended in ICH GCP guidance: ‘In general there is a need for on-site monitoring …’ (section 5.18.3). 1 Through that guidance, and following high-profile data fraud cases, 2 on-site monitoring has become a standard means of ensuring GCP compliance since the 1990s, at least in industry-sponsored trials. Visit activities commonly include intensive document review, in particular, source data verification (SDV): the process of checking case report form data against source notes. While this may be done in a sample of patients, or on selected data items on all patients, many trials’ site visits aim to check 100% of trial data. 3 Intensive on-site monitoring has been highlighted as inefficient and associated with significant costs 4 – 9 which are passed down to patients and healthcare systems as drug development expenses. 2 , 4

A growing body of evidence shows that 100% SDV is of limited value. 10 – 13 Trialists 14 , 15 and regulators 16 – 18 have expressed support for ‘risk-based monitoring’, recognising that not all clinical trials require the same approach to quality control and assurance. This is reflected in the update of ICH GCP E6. 19

One risk-based approach is ‘triggered’ or ‘targeted’ on-site monitoring. It was suggested as a possible option for trials of investigational medicinal products classed as low or medium risk by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, Medical Research Council (MRC), and UK Department of Health. 16 An initial risk assessment determines the key risks resulting from the intervention and the design of the trial and strategies to minimise those risks are specified. If triggered monitoring is selected, over the course of the trial sites are prioritised for visits based on central monitoring ‘triggers’: predefined indicators such as number of protocol deviations, case report form return rates, uncommon patterns of serious adverse event reporting or subjective assessments of site performance. Such targeted monitoring is also mentioned as a possible approach in the update to ICH GCP E6. 19

Although triggered monitoring approaches are not uncommon 3 and have clear potential benefits in terms of resource-use, there is no empirical evidence to show how well they work. TEMPER was designed to provide such evidence.

Study design

TEMPER is a prospective, matched-pair study assessing the value of triggered monitoring in distinguishing sites with important protocol or GCP compliance issues not identified centrally. Trials unit teams used triggers to identify sites to visit (‘triggered visit’). Each of these was matched with an ‘untriggered site’, and the paired sites were visited and monitored according to the trial’s monitoring plan. Site visit findings were categorised according to a standard classification based on a high-level summary ( Table 1 ). We compared the proportion of triggered and untriggered visits with ≥1 Major/Critical finding not identified through central monitoring or previous visits. The study design is summarised in Figure 1 . We developed a bespoke system, the TEMPER Management System (TEMPER-MS) to support implementation of the study. 20

Classification of monitoring findings in TEMPER.

TEMPER study design.

Ethics committee advice deemed no ethical review was required because the additional site visits were within the scope of each trial’s monitoring plan. To ensure visits were arranged and conducted as per normal practice, site staff were not explicitly informed about the TEMPER study or the reason for a monitoring visit.

Trial selection

Included trials were conducted and monitored by the MRC Clinical Trials Unit at University College London; sponsored by the UK MRC; employing a triggered monitoring strategy; investigational medicinal products risk category B (‘somewhat higher risk than standard medical care’) according to MRC/Department of Health/Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency risk classification. 16 Trials also needed to have started recruitment before 2012 and plan follow-up to continue until after 2014.

Triggers were based on those in use in the selected trials, with some additional quantification where thresholds of concern had not previously been defined. The triggers were mainly quantitative although subjective ‘general concerns’ could also be added to each site’s overall trigger score in response to, for example, worrying contact with a site or other more objective concerns not captured by the trial’s triggers. As risks and monitoring needs changed over time, some new triggers were added and/or thresholds modified (e.g. one trial demanded a higher threshold for data return ahead of an interim analysis). Table 2 summarises and exemplifies the trigger types used by trial at the completion of TEMPER.

Trigger types used during the course of TEMPER by trial.

CRF: case report form; SAE: serious adverse event.

Site selection

We scheduled regular ‘trigger meetings’ (3–6 monthly or more frequently if required) with trials unit teams to review trigger data. Sites’ trigger scores were calculated by the TEMPER-MS and reviewed by the trial teams to decide which sites to visit. Chosen sites usually had the highest total trigger scores, but general concerns sometimes led to other sites being prioritised. All trigger meeting discussions were documented.

To replicate real-life prioritisation by resource-limited trial teams, we asked teams to distinguish between sites that would definitely be visited in normal practice (‘triggered-and-usually-visited’); and those, usually with lower trigger scores, considered lower priority for a visit at that time (‘triggered-but-not-usually-visited’); both are grouped as ‘triggered visits’ for the primary analysis.

The TEMPER-MS matching algorithm proposed ‘untriggered’ sites to visit, minimising differences in (1) number of patients and (2) time since first patient randomised, while maximising differences in trigger score (see Appendix in Supplementary Material and Diaz-Montana et al. 20 ). The closest match was accepted, unless there were clearly documented reasons not to. For example, an untriggered site that had been visited very recently outwith TEMPER was replaced with the next closest match.

Site visits

To maximise similarity between triggered and untriggered monitoring visits, they were all conducted according to the trial’s monitoring plan with the same planned checks at all visits in addition to follow-up of any specific concerns raised by the trials unit team. These were broadly similar across the trials in the study: monitoring usually included SDV on a sample of patients and review of consent forms, pharmacy documents and facilities, and Investigator Site Files.

We aimed to conduct all visits within 3 months after the trigger meeting, with paired visits as close together as possible, and no more than 28 days apart. The triggered visit was planned before its untriggered match to help ensure that any changes to monitoring visit approach implemented by the trial team at the time of the triggered visit could be reflected in the paired visit. All monitors performed the same roles at site visits. Triggered visits were attended by TEMPER-specific and trial-specific monitors, untriggered visits only by TEMPER monitors. The same GCP and monitoring training was undertaken both by the trial team members attending visits and the monitors; the latter also received trial-specific training. A TEMPER-specific monitoring visit report ensured consistent reporting. Reports were written and followed-up according to each trial’s monitoring plan and trials unit procedures.

Data collection, finding classification and endpoint definition

Findings were classified as ‘Critical’, ‘Major’ or ‘Other’ (see Table 1 ), with their final grade taking account of any relevant response from the site to the monitoring report. All Critical and Major findings were further categorised as new or ‘already known prior to the monitoring visit’ (e.g. through central monitoring or self-reporting by the site). The latter were excluded from the primary outcome, but included in the monitoring report to allow follow-up to resolution by the trial team as required. The protocol provided detailed guidance on appropriate gradings (see Online Supplementary Material ). This was updated to incorporate new findings as they arose. Selected findings (related to consent and missed serious adverse events in particular), if repeated to a predefined level, could be ‘upgraded’ from ‘Other’ to ‘Major’ or from ‘Major’ to ‘Critical’. In these cases, one additional finding of the higher grade was added to the total findings for that visit.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of sites with ≥1 Major or Critical finding not already identified through central monitoring or a previous visit (‘new’ findings). Secondary outcomes were number of Major and Critical findings, proportion of sites with ≥ 1 Critical finding, number of Critical findings and category of Major/Critical findings.

Sample size

Sample size calculations, based on review of previous trials unit monitoring reports from trials using triggered monitoring, assumed ∼70% of triggered visits would produce ≥1 new Major/Critical finding. To detect an absolute reduction of ≥30% (from 70% to 40%) in untriggered sites, with 80% power and two-sided significance level of 5%, required ∼84 site visits in 42 matched pairs. We sought balanced numbers of visits across trials and required ≥50% of each trial’s triggered visits to be ‘triggered and usually visited’. Ten additional, unmatched visits were made to high recruiting sites not otherwise selected for visits, to allow further assessment of ‘high recruitment’ as a predictor of findings in secondary analyses.

The primary analysis was a two-group comparison of the proportion of sites with ≥1 new Major/Critical finding in the triggered versus untriggered groups. Analyses of total numbers of Major and Critical findings used one-sample t-tests of the within-pair differences. Prior to the first analysis, the TEMPER Endpoint Review Committee recommended a sensitivity analysis to exclude all findings related to re-consent, as these typically communicated minor changes in side-effect profile that could have been communicated without requiring re-consent. A second, exploratory analysis, excluded all consent-related findings because previous research suggested that these could likely be identified centrally. 21 , 22

In secondary analyses, using all 94 visits, and with additional information of potential prognostic value obtained from questionnaires completed by the Trials unit and site staff prior to the monitoring visits (see Online Supplementary Material ), the ability of individual triggers and site characteristics to predict on-site findings was assessed by comparing the proportion of visits with the outcome of interest (Eg ≥ 1 Major/Critical finding) at sites where a trigger had/had not fired. This utilised chi-square tests (with trend for ordered categories) or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate for univariate analyses and logistic regression for multivariate analyses.

Consistency

To reduce intra- and inter-observer bias, in addition to Monitor training and the use of the categorisation system, a Consistency Monitoring Group, comprising trials unit staff from the participating trials’ teams, discussed suitable gradings for findings. The Endpoint Review Committee comprised four experienced trialists from the trials unit with no direct link to the trials, and reviewed, for all visit reports and blind to whether the visit was triggered or untriggered, all Major and Critical findings and a selection of Other findings. They also performed cross-visit reviews of similar sorts of findings to ensure consistency of grading. The categorisation appendix and grading of relevant findings from previous visits were updated if required following Consistency Monitoring Group or Endpoint Review Committee discussions.

Three trials were included; all randomised, multicentre (>100 sites) cancer treatment trials with a time-to-event outcome measure (recurrence-free or overall survival), planned accrual of >1000 patients and paper-based data collection.

Site selection and matching

In total, 23 trigger meetings and 84 paired monitoring visits took place between 2013 and 2016 ( Figure 1 ). Triggered and untriggered sites had mean trigger scores of 4.0 (range of 2–6) and 0.8 (range of 0–3), respectively. The matching algorithm gave mean within-pair differences (triggered–untriggered) of -1.4 months (70.1 vs 71.5) in time since first randomisation and +8.5 (49.9 vs 41.4) in patients randomised.

Visit conduct

Three visits were >1 week outside the 3-month visit window. Five untriggered visits were >28 days after their triggered match, the longest gap being 4 months; the continued suitability of the untriggered match as a control was confirmed at the next trigger meeting. One untriggered visit was before its triggered match because of a short-notice postponement.

The median (interquartile range) number of trials unit staff attending triggered and untriggered visits was 3 (2–3) and 2 (2–2), respectively (Wilcoxon p < 0.01). Visit conduct within pairs was similar in most respects: full Investigator Site File checks were done at 25/42 triggered and 27/42 untriggered visits (p = 0.65), pharmacy facility checks at 25 and 29, respectively (p = 0.36), while the median (interquartile range) number of patients undergoing SDV was 4 (3–5) and 4 (3–5), respectively (paired t-test p = 0.08). However, more consent forms were checked at triggered (median (interquartile range): 44 (27–77)) than untriggered visits (35 (18–70)) (paired t-test p = 0.01).

Primary outcome: Major/Critical findings

Table 3 summarises all Major and Critical findings, and Table 4 summarises the primary outcome; 88.1% of triggered visits had ≥1 new Major/Critical finding, compared to 81.0% of untriggered visits, an absolute difference of 7.1% (95% confidence interval (CI) –8.3%, +22.5%; p = 0.365). When re-consent findings were excluded, these figures reduced to 85.7% versus 59.5% (difference = 26.2% (95% CI 8.0%, 44.4%; p = 0.007)); while excluding all consent and re-consent findings reduced them further to 69.0% versus 45.2% (difference = 23.8% (95% CI 3.3%, 44.4%; p = 0.027)). Findings by trial are summarised in Table S1 in the Online Supplementary Material .

Summary of Major and Critical findings at TEMPER monitoring visits.

CRF: case report form; SDV: source data verification; SAE: serious adverse event.

Primary and secondary binary outcomes.

CI: confidence interval.

Secondary outcomes

Critical findings ( Online Supplementary Material Table S2 ) were almost solely from consent form and source data reviews. The majority (59%) were upgrades because of a cumulative number of Major findings, and the remainder were graded Critical in their own right. The proportion of visits with Critical findings was approximately halved in untriggered visits, but these differences were of borderline statistical significance ( Table 4 ).

The median number of new Major and Critical findings ( Table 5 ) was three at triggered visits and one at untriggered visits; the mean within-pair difference was 1.40 (95% CI –0.72, 3.53; p = 0.19) for all findings, 1.05 (95% CI 0.032, 2.06; p = 0.044) excluding re-consent findings and 0.48 (95% CI –0.12, 1.08; p = 0.12) excluding all consent findings (when the median number of findings was 1 and 0, respectively). The median number of new Critical findings was zero at all visits.

Secondary continuous outcomes.

Prognostic value of individual triggers

The ability of specific triggers to predict the presence of Major and/or Critical findings at the site visit was assessed across all outcomes ( Online Supplementary Material Tables S3 and S4 ). While the finding rates tended to be higher when the trigger had been fired at the time of site selection, only three triggers showed even a modest association with outcome (p < 0.05 for at least one outcome, no adjustment for multiple testing). These were ‘data query resolution time’, ‘protocol deviation’ and ‘general concern’. Multivariate analyses were carried out for each outcome measure, but resulted in univariate models only, namely, the trigger with the strongest association with that outcome measure in the univariate analysis.

High-recruiting sites were defined as the top 10% of trial sites ordered by recruitment at the time of the site visit. The prognostic value of high recruitment on outcomes was investigated excluding all consent findings, as the number of consent forms checked was directly related to number of patients. We found no evidence of higher finding rates at these sites.

Other site characteristics

Trials unit teams completed 90/94 pre-visit questionnaires. There was no clear evidence of a linear relationship between the trial team ratings and the presence of Major or Critical findings, including or excluding consent findings (data not shown).

Pre-visit site questionnaires were provided by 76/94 sites. There was no evidence of a linear association between the chance of ≥1 Major/Critical finding and the number of active trials either per site or per staff member. There was, however, evidence that the greater the number of different trial roles undertaken by the Research Nurse, the lower the probability of Major/Critical findings. To a lesser extent, the reverse was true for the principal investigator (see Online Supplementary Material Table S5 ).

We have shown that triggered monitoring, as used in these trials, did not satisfactorily distinguish sites with higher and lower levels of concerning on-site monitoring findings. The pre-specified primary comparison showed no significant difference between triggered and untriggered visits in the proportion with ≥1 Major/Critical finding not previously identified centrally. However, over 70% of on-site findings related to issues in recording informed consent, and 70% of these to re-consent; the pre-specified sensitivity analysis excluding re-consent findings demonstrated a clear difference in event rate. There was some heterogeneity between trials in the primary comparison, but much greater consistency in the sensitivity and secondary analyses. In addition, there was some evidence that the trigger process used could identify sites at increased risk of serious concern: around twice as many triggered visits had ≥1 Critical finding, in the primary and sensitivity analyses. Thus, we would suggest that triggered monitoring has promise, but clearly needs refinement.

The categorisation framework we used is, we believe, similar to those applied by regulators to the same findings. However, these typically identify a finding of importance in relation to an individual patient, when it is only by accumulation that these are likely to have serious impact on the trial as a whole. Risk-based monitoring is not looking for perfection in trial data or conduct, but to detect errors that really matter. We found no visit findings that raised serious issues that would apply across sites, involved serious trial-wide safety issues, or suggested any biases across trial arms which would impact credibility of the trials’ results.

The prevalence of sites with Major and Critical findings was higher than expected, echoing the experience of others. 23 However, the great majority of our findings, like others’, 24 related to documenting the consent process, for example, ensuring that correct versions are used, and signatures and dates are present and consistent with the timing of randomisation. The ‘quality by design’ concept 25 states the first course of action should be preventive; informed consent form templates used by academic clinical trials units should, therefore, be reviewed to see if their design can be improved and completion errors reduced. Timely central monitoring of consent forms with adequate anonymisation 22 may mitigate the effects of many consent form completion errors, particularly if trial treatment timelines mean that full consent forms – or at least selected items – can be reviewed before randomisation.

Re-consent was usually provoked by updates to drug safety information, of which participants (at least those still on treatment) should be aware. This can be a lengthy process and therefore difficult to monitor centrally. When re-consent is explicitly required, better central monitoring methods are possible, perhaps using site logs with lists of expected visit dates. However, although regulatory guidance is clear that participants must be informed about significant trial updates, the method is not specified. 19 Research Ethics Committees and Institutional Review Boards may prefer formal, documented informed re-consent, but this may not always be necessary. Waiting until the participant’s next trial visit may sometimes be inferior (certainly in terms of speed) to sending an immediate letter to the participants explaining the changes and asking them to contact their site only if they have concerns.

Beyond consent processes, the majority of other findings were identified from SDV activities. A growing body of evidence suggests intensive SDV is often of little benefit to randomised controlled trials, with any discrepancies found having minimal impact on the robustness of trial conclusions. 11 , 12 , 26 SDV for a sample of participants may be sufficient to detect systematic problems, 27 , 28 and focussing SDV only on key data items may be appropriate and rational.

We carried out exploratory analyses of the prognostic value of individual triggers to see if visits to sites at which a specific trigger had fired were substantially more likely to find Major or Critical findings than visits to sites at which this trigger was not fired. The sample size was sufficient to detect an absolute difference of approximately 30% in finding rates. Some triggers, including high or low serious adverse event rates, were rarely met so their prognostic value could not be assessed. Three triggers were of potential, though still at best modest value, given the multiple outcome measures assessed: the speed of data query resolution, protocol deviations and ‘general concern’. These triggers were not wholly independent, and it was not possible to combine them in a way that improved finding rate discrimination more than our triggered/not triggered visit categorisation. We note that high recruitment and poor case report form return rates, although commonly used as triggers 3 were not of clear prognostic value.

Analysis of site staffing and workload suggested that the fewer trial responsibilities held by the research nurse, the higher the chance of a Major/Critical finding, with a trend to the converse (mainly when findings relating to consent are excluded), in relation to the principal investigator. These findings suggest that, while an insufficiently supported and possibly overstretched investigator may impact adversely on trial conduct, an experienced, capable local Research Nurse, able to take responsibility for many elements of trial conduct, is key.

Ultimately, the sensitivity and specificity of triggered monitoring depends on the selection of triggers. We found Major and Critical findings at untriggered visits, suggesting it remains necessary to visit these sites unless central monitoring techniques can be improved or the discriminatory value of triggers can increase. We used the trials’ existing triggers – quantified more precisely where needed to facilitate ranking of sites – without any prior assessment of their potential value. The search for more discriminatory triggers should encompass work on Key Performance Indicators 29 and Central Statistical Monitoring. 30 Subjective assessments may be of value, but are perhaps more prone to inconsistency, particularly when staff turnover is high, and therefore, harder to generalise. We might also optimise current triggers, for example, with better (non-dichotomous) treatment of continuous variables or greater incorporation of temporal trends.

Planning, conducting and follow-up on monitoring visits is time-consuming and therefore costly, 2 , 8 , 9 so maximising cost-benefit is key. We did not routinely use triggers to guide the content of site visits which was perhaps not optimal. Refined triggers could target specific activities, for example, data quality issues could provoke SDV visits and general concerns could provoke additional training. Prospective study of trigger-defined visits is warranted.

Central monitoring enables review of information across sites and time without the time constraints of a site visit. Maximising these strengths would free more time at visits for targeted SDV and activities best done in-person, for example, process review, building rapport or training.

We acknowledge several limitations. TEMPER was conducted in only three trials of similar type although we see no reason to doubt its applicability to other trials. The trials unit staff present at triggered and untriggered visits were not blind to visit type. TEMPER monitors were at all visits, but trial team staff were only required to attend triggered visits. However, the additional staff at triggered visits often included new trial staff attending for training purposes and the planned activities were the same at all visits. The only notable difference in completed activity within pairs was the number of consent forms checked, which was higher in the triggered visits compared to the untriggered visits. While this could have increased the chance of findings at triggered visits, this appears not to have been the case, the difference in finding rates being greater when consent findings were excluded. Observation bias due to lack of blinding of monitoring staff was mitigated by consistent training on the trials and monitoring methods, the use of a common finding grading system and independent review of all Major and Critical findings which was blind to visit type.

The sample size was modest, but nonetheless adequately powered to detect the minimal differences in visit finding rates necessary to support the triggered monitoring strategy employed in these trials. TEMPER assessed the value of pre-existing triggers, rather than first exploring the best triggers. Evidence to support triggered monitoring comes largely from our sensitivity and exploratory analyses, although these were pre-planned, and recommended by an independent committee, which was blind to visit type.

Research into trial conduct rarely has the rigour we demand of clinical trials. The motivation to study this area comprises (1) the need to monitor trials effectively, minimising risk to patients’ rights and safety and protecting data integrity and (2) the need to do so in a cost-effective manner, noting that monitoring activities are a major component of trial conduct costs at the coordinating centre. TEMPER is one of the few studies to address monitoring strategies in a prospective manner, 23 , 31 , 32 and the first, we believe, to specifically evaluate triggered monitoring. Its results should help challenge and guide the future use of triggered monitoring.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors acknowledge the teams working on the trials that took part in TEMPER, the Endpoint Review Committee and Consistency Monitoring Group, previous TEMPER Study Monitors and study team members, Matt Nankivell for conducting the independent validation analyses, staff at sites who participated in TEMPER study visits and Sharon Love and Director of MRC Clinical Trials Unit at University College London, Mahesh Parmar, for review of the final manuscript. The results were presented at the Joint 2017 International Clinical Trials and Methodology Conference (ICTMC) and Society for Clinical Trials (SCT) meeting, Liverpool, UK, May 2017.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This work was supported by the Cancer Research UK (grant C1495/A13305 from the Population Research Committee); additional support was provided by the Medical Research Council (MC_EX_UU_G0800814) and the MRC London Hub for Trial Methodology Research (MC_UU_12023/24).

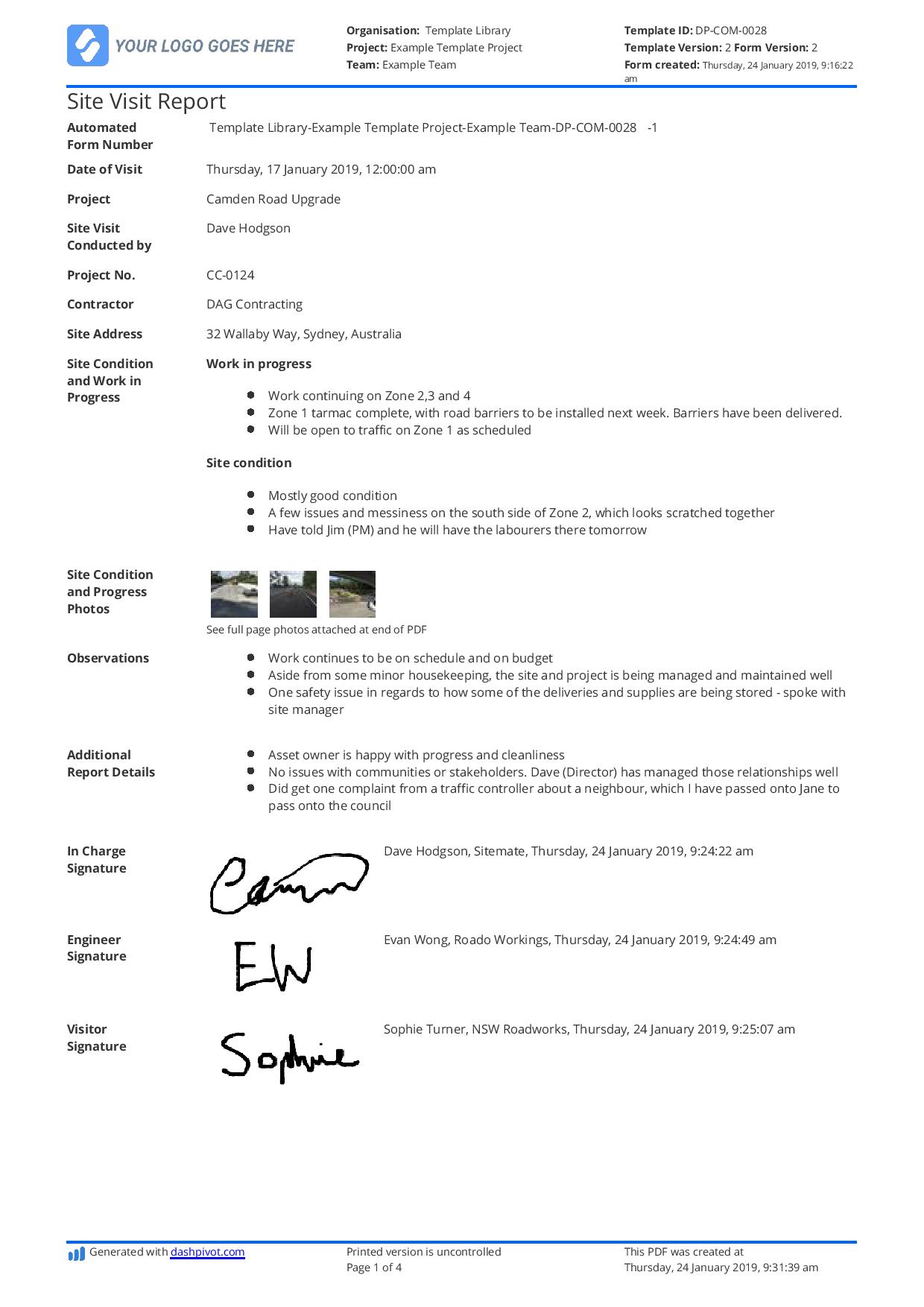

Construction Site Visit Report Template and Example

Start with a free 30-day trial. No credit card required.

This construction site visit report template makes your site visits and site visit reports easier, more organised and more professional.

Trusted by over 250,000 people from built-world companies of all sizes

~200 employees

~20 employees

~25,000 employees

~40 employees

~10,000 employees

~1,500 employees

~35,000 employees

Preview how this construction site visit report template works below

Try using the interactive site visit report template preview below

Use this construction site visit report template for free.

This construction site visit report sample is powered by dashpivot..

- Access and complete your site visit report on any device - mobile, tablet or computer.

- Print, send or download your site visit reports in PDF or CSV formats with your company logo

- Store and manage your site visit reports online where they are easily searchable and always organised

- Customise the site visit report template in seconds with drag-and-drop functionality

- Convert your site visit reports from timeline view into a register instantly, to eliminate manual data entry

Dashpivot is user friendly software trusted by built world companies of every size all over the world.

Templates allow for better, customised site visit reports with automations

Form builder, spreadsheet view, timeline view, convert your manual site visit reports into smart digital reports to save time and reduce errors..

Create or customise your construction site visit reports with the simple drag-and-drop form builder, or use the free digital construction site visit report template to get started straight away or make minor adjustments to suit your needs.

Powerful fields enable you to choose how information is captured and managed within forms to save time and improve data accuracy.

Switch to Timeline view to see an overview of all submitted site visit reports

Register view is great for seeing a spreadsheet view of reports, but the Timeline view is great for seeing a quick overview of reports submitted by date.

You can choose which tag is showing with the report to make for easy organisation - common tags used are location, project or team to quickly see how each selection is performing.

View detailed information on your site visit reports in the Register view.

Say goodbye to filling in forms and maintaining spreadsheets and 'databases' as well. Dashpivot can convert all of your information into a register in a single click so you don't have to manage multiple sources of information.

Ensure submitted site visit reports are actioned with automated workflows

Workflows enable you to setup simple yet powerful automations which notify chosen people at certain stages of a process. View these workflows to see the current status of your site visit reports so nothing important ever gets missed.

Standardise your construction quotation templates and build powerful automations to eliminate data entry and double-handling

Other popular templates you can use and customise for free.

Construction Log Book template

Make your log book easier to complete, share and organise with this digital log book template.

Construction Work Order template

This construction work order template can be used and adapted for any work order, to make your communications more efficient and more reliable.

Construction Stop Work Order template

This construction stop work order template ensures your stop work orders never get missed or ignored.

Build digital processes around your site visits

Take the digital template a step further by using a digital app to help create and manage your site visit reports.

Allow your team to record new site visit reports or access existing site visit reports on site via their mobile or tablet.

Take photos on site and attach them directly to your reports.

Streamline all of your commercial processes in one place

If you're running site visit reports, there are other documents and processes you're running on a daily, weekly and monthly basis.

Make it easy for your team to fill out standardised reports and forms across all of their responsibilities with everything they need in one place.

Sitemate builds best-in-class software tools for built world companies.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The purpose of a monitoring visit (sometimes called a supervision visit or a field visit) is to make sure that project activities are implemented the way they are described in the plan. It normally involves meeting with the people running the project, meeting with the participants, and observing the activities. At the end of a monitoring visit, it is important to prepare a report that ...

An experienced CRA may follow all the rules and requirements for writing a site monitoring visit report (SMVR), but there are nuances that can make the difference between a report that simply follows that formula and one that really paints a picture its audience can understand. Roslyn Hennessey, senior project manager at Westat describes the ...

The up-to-date and user-friendly Monitoring Visit Report Template can be used to report monitoring visits. This template facilitates step-by-step reporting of all matters relevant to the reporting of monitoring visits. The template includes an action list and practical drop-down menus. It is part of a series of monitoring templates that includes:

Bring clinical trial monitoring tools! Use the Visit To Do List to stay focused and on task. Provide the site staff with a copy of the Action Item List - and use the other copy to write the Monitoring Visit Report and Follow-Up Letter. For more tips, check out Dan Sfera's YouTube video about how CRAs should prepare for a site monitoring visit.

Using the Site Monitoring Visit Report. The Site Monitoring Visit (SMV) Report has been developed to help ensure comprehensive and consistent monitoring of 21st Century Community Learning Centers (CCLC) in New York State. While this document is intended for use by program reviewers, it is also recommended for use by sub-grantees to (1) guide ...

A site visit report is a formal document that provides a detailed account of a visit to a particular location or project site. It records the observations, activities, conditions, discussions, and any deviations or issues identified during the visit. The report often includes recommendations or action items based on these findings.

Here's a sample format for your next Site Visit Report. Report Title: Site Visit Report Project Name: [Project's Name] Location of Site: [Site's Address] Date of Visit: [Date, e.g., September 13, 2023] Report Prepared By: [Your Name/Team's Name] 1. Introduction: A brief description of the site and the project. Mention any background information pertinent to the visit.

A site visit report serves as a crucial tool in the realm of project management, bridging the gap between on-ground realities and managerial oversight. Its primary purpose is to document firsthand observations, activities, and conditions of a specific site at a given time, offering a snapshot of the project's progress, challenges, and ...

Each monitoring visit is an integral part of the clinical research process. In conclusion, the different types of monitoring visits, PSVs, SIVs, IMVs, and COVs, are designed to ensure that the study is being conducted in a way that the subjects are safe and the data is valid. The CRA must ensure that sites are performing the study in compliance ...

On Site Monitoring Visit Report Template TOOL 1.5.3 INSTITUTIONAL LOGO Monitoring Visit Report (On-Site) Protocol title (short) Protocol number Site Investigator Date of visit (day/month/year) Monitor Attendees The following personnel attended this initiation Name (last, first) Title Survey role

Regular site monitor visits can be broken down into four types: pre-study visits, initiation visits, periodic monitoring visits, and close-out visits. Study sites may also be monitored or audited by the FDA, Clinical Research Organizations (CROs), IRBs and sponsors. For more information on site audits by outside entities please visit the training documents on Quality Management: Audits.

Initial (first)monitoring visit. If you were recently hired for a CRA position in a new pharmaceutical company, you would need to do the next steps prior to scheduling the first monitoring visit: - Familiarize with the company's general SOPs and Sponsor's study-specific SOPs (if applicable) relating to the clinical study initiation ...

Site monitoring reports serve a regulatory purpose by proving the site monitoring happened. Their usefulness extends beyond simply checking a box on the compliance checklist. A well-written report shouldn't be an afterthought but should be an integral part of the site visit. The report and visit are essential parts of proper clinical trial ...

The up-to-date and user-friendly Monitoring Site Initiation Visit (SIV) Report Template can be used to report a site initiation visit. This template is a step-by-step checklist with convenient drop-down lists. It guides monitors through all the important aspects of a site initiation visit (SIV), so they can assess whether a site is ready to ...

Here's a breakdown of what should typically be included in a site visit report report: Project Reference: The construction project name and reference ID. Location: The exact address or co-ordinates of the construction site. Date of Site Visit: The specific date (s) when the visit was recorded. Prepared By: The name of the individual or team ...

The same GCP and monitoring training was undertaken both by the trial team members attending visits and the monitors; the latter also received trial-specific training. A TEMPER-specific monitoring visit report ensured consistent reporting. Reports were written and followed-up according to each trial's monitoring plan and trials unit procedures.

There will be many good tips to help you with monitoring visit report completion. So, for those of you that don't know, let's start with the guidelines. Per ICH/GCPs, the monitor should submit a written report to the sponsor after each trial site visit or trial related communication. The guidelines also state what each report should include ...

For each activity, OUs must perform site visits to provide oversight over agreements/awards, inspect implementation progress and deliverables, verify monitoring data, and learn from implementation. While each Mission and the activity's context should inform the number and frequency of site visits, in general, Missions should conduct site ...

These guidelines describe the procedures before, during, and following a monitoring visit. These procedures may vary depending on the type of study and the type of visit being conducted: site assessment visit, site initiation visit, site interim monitoring visit, for cause visit, or site close-out visit.

Monitoring Visit Number (2) - Date (04-12-2019) Page 2 of 12 AHRC Monitoring Visit Report Template Version 1.0 12JUL2019 identified and can be found in page 2. Site staff remain accommodating and a pleasure to work with. The organization and cooperation of the site staff was greatly appreciated by the monitors.

Start with a free 30-day trial. No credit card required. This construction site visit report template makes your site visits and site visit reports easier, more organised and more professional. 100% fully customisable construction site visit report template. Export your site visit report to PDF or CSV. Access reports on mobile, tablet or computer.

5.18.6 Monitoring Report. ADDENDUM. The monitor should submit a written report to the sponsor after each trial-site visit or trial-related communication. Reports should include the date, site, name of the monitor, and name of the investigator or other individual(s) contacted.

Monitoring Guidelines and SOP Manual Document Control Doc. No.: FORM 004 Rev. No.: 0 Date: Page: 1 of 8 SITE INITIATION VISIT REPORT Protocol: PI Name: PI Address: Date of Visit: Monitor(s): Other Sponsor Personnel Present: Site Personnel Present at Visit (include names and titles): PROCEDURAL REVIEW