Advertisement

How Time Travel Works

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

Time Travel Paradoxes

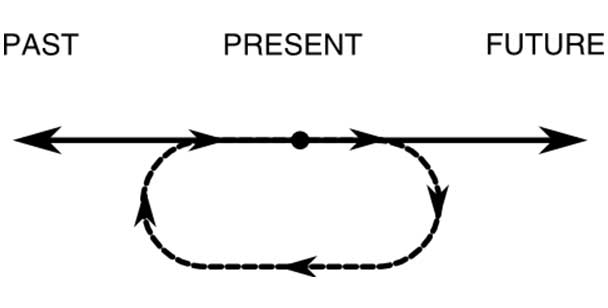

As we mentioned before, the concept of traveling into the past becomes a bit murky the second causality rears its head. Cause comes before effect, at least in this universe, which manages to muck up even the best-laid time traveling plans.

For starters, if you traveled back in time 200 years, you'd emerge in a time before you were born. Think about that for a second. In the flow of time, the effect (you) would exist before the cause (your birth).

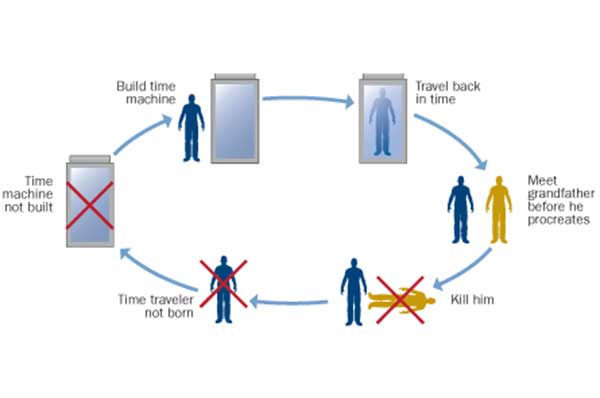

To better understand what we're dealing with here, consider the famous grandfather paradox . You're a time-traveling assassin, and your target just happens to be your own grandfather. So you pop through the nearest wormhole and walk up to a spry 18-year-old version of your father's father. You raise your laser blaster , but just what happens when you pull the trigger?

Think about it. You haven't been born yet. Neither has your father. If you kill your own grandfather in the past, he'll never have a son. That son will never have you, and you'll never happen to take that job as a time-traveling assassin. You wouldn't exist to pull the trigger, thus negating the entire string of events. We call this an inconsistent causal loop .

On the other hand, we have to consider the idea of a consistent causal loop . While equally thought-provoking, this theoretical model of time travel is paradox free. According to physicist Paul Davies, such a loop might play out like this: A math professor travels into the future and steals a groundbreaking math theorem. The professor then gives the theorem to a promising student. Then, that promising student grows up to be the very person from whom the professor stole the theorem to begin with.

Then there's the post-selected model of time travel, which involves distorted probability close to any paradoxical situation [source: Sanders]. What does this mean? Well, put yourself in the shoes of the time-traveling assassin again. This time travel model would make your grandfather virtually death proof. You can pull the trigger, but the laser will malfunction. Perhaps a bird will poop at just the right moment, but some quantum fluctuation will occur to prevent a paradoxical situation from taking place.

But then there's another possibility: The quantum theory that the future or past you travel into might just be a parallel universe . Think of it as a separate sandbox: You can build or destroy all the castles you want in it, but it doesn't affect your home sandbox in the slightest. So if the past you travel into exists in a separate timeline, killing your grandfather in cold blood is no big whoop. Of course, this might mean that every time jaunt would land you in a new parallel universe and you might never return to your original sandbox.

Confused yet? Welcome to the world of time travel.

Explore the links below for even more mind-blowing cosmology.

Related Articles

- How Time Works

- How Special Relativity Works

- What is relativity?

- Is Time Travel Possible?

- How Black Holes Work

- How would time travel affect life as we know it?

More Great Links

- NOVA Online: Time Travel

- Into the Universe with Stephen Hawking

- Cleland, Andrew. Personal interview. April 2010.

- Davies, Paul. "How to Build a Time Machine." Penguin. March 25, 2003.

- Davies, Paul. Personal interview. April 2010.

- Franknoi, Andrew. "Light as a Cosmic Time Machine." PBS: Seeing in the Dark. March 2008. (March 1, 2011)http://www.pbs.org/seeinginthedark/astronomy-topics/light-as-a-cosmic-time-machine.html

- Hawking, Stephen. "How to build a time machine." Mail Online. May 3, 2010. (March 1, 2011)http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/moslive/article-1269288/STEPHEN-HAWKING-How-build-time-machine.html

- "Into the Universe with Stephen Hawking." Discovery Channel.

- Kaku, Michio. "Parallel Worlds: A Journey Through Creation, Higher Dimensions, and the Future of the Cosmos." Anchor. Feb. 14, 2006.

- "Kerr Black Holes and time travel." NASA. Dec. 8, 2008. (March 1, 2011)http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/ask_astro/answers/041130a.html

- Sanders, Laura. "Physicists Tame Time Travel by Forbidding You to Kill Your Grandfather." WIRED. July 20, 2010. (Mach 1, 2011)http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2010/07/time-travel/

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

The Time-Travel Paradoxes

What happens if a time traveler kills his or her grandfather? What is a time loop? How do you stop a time machine from just appearing somewhere in space, millions of kilometers from home? And is there such a thing as free will?

Congratulations! You have a time machine! You can pop over to see the dinosaurs, be in London for the Beatles’ rooftop concert, hear Jesus deliver his Sermon on the Mount, save the books of the Library of Alexandria, or kill Hitler. Past and future are in your hands. All you have to do is step inside and press the red button.

Wait! Don’t do it!

Seriously, if you value your lives, if you want to protect the fabric of reality – run for the hills! Physics and logical paradoxes will be your undoing. From the grandfather paradox to laws of classic mechanics, we have prepared a comprehensive guide to the hazards of time travel. Beware the dangers that lie ahead.

The Grandfather Paradox

Want to change reality? First think carefully about your grandparents’ contribution to your lives.

The grandfather paradox basically describes the following situation: For some reason or another, you have decided to go back in time and kill your grandfather in his youth. Yeah, sure, of course you love him – but this is a scientific experiment; you don’t have a choice. So your grandmother will never give birth to your parent – and therefore you will never be born, which means that you cannot kill your grandfather. Oh boy! This is quite a contradiction!

The extended version of the paradox touches upon practically every single change that our hypothetical time traveler will make in the past. In a chaotic reality, there is no telling what the consequences of each step will be on the reality you came from. Just as a butterfly flapping its wings in the Amazon could cause a tornado in Texas, there is no way of predicting what one wrong move on your part might do to all of history, let alone a drastic move like killing someone.

There is a possible solution to this paradox – but it cancels out free will: Our time traveler can only do what has already been done. So don’t worry – everything you did in the past has already happened, so it’s impossible for you to kill grandpa, or create any sort of a contradiction in any other way. Another solution is that the time traveler's actions led to a splitting of the universe into two universes – one in which the time traveler was born, and the other in which he murdered his grandfather and was not born.

Information passage from the future to the past causes a similar paradox. Let’s say someone from the future who has my best interests in mind tries to warn me that a grand piano is about to fall on my head in the street, or that I have a type of cancer that is curable if it’s discovered early enough. Because of this warning, I could take steps to prevent the event – but then, there is no reason to send back the information from the future that saves my life. Another contradiction!

Marty finds himself in hot water with the grandfather paradox, from ‘Back to the Future’ 1985

Let’s now assume the information is different: A richer future me builds a time machine to let the late-90s me know that I should buy stock of a small company called “Google”, so that I can make a fortune. If I have free will, that means I can refuse. But future me knows I already did it. Do I have a choice but to do what I ask of myself?

The Time Loop

In the book All You Zombies by science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein the Hero is sent back in time in order to impregnate a young woman who is later revealed to be him, following a sex change operation. The offspring of this coupling is the young man himself, who will meet himself at a younger age and take him back to the past to impregnate you know whom.

Confused? This is just one extreme example of a time loop – a situation where a past event is the cause of an event at another time and also the result of it. A simpler example could be a time traveler giving the young William Shakespeare a copy of the complete works of Shakespeare so that he can copy them. If that happens, then who is the genius author of Macbeth?

This phenomenon is also known as the Bootstrap Paradox , based on another story by Heinlein, who likened it to a person trying to pull himself up by his bootstraps (a phrase which, in turn, comes from the classic book The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen). The word ‘paradox’ here is a bit misleading, since there is no contradiction in the loop – it exists in a sequence of events and feeds itself. The only contradiction is in the order of things that we are acquainted with, where cause leads to effect and nothing further, and there is meaning to the question “how did it all begin?”

Terminator 2 (1991). The shapeshifting android (Arnold Schwarzenegger) destroys himself in order to break the time loop in which his mere presence in the present enabled his production in the future

Time travelers – where have all they gone?

In 1950, over lunch physicist Enrico Fermi famously asked: “If there is intelligent extraterrestrial life in the Universe – then where are they?” indicating that we have never met aliens or came across evidence of their existence, such as radio signals which would be proof of a technological society. We could pose that same question about time travelers: “If time travel is possible, where are all the time travelers?”

The question, known as the Fermi Paradox, is an important one. After all, if it were possible to travel through time, would we not have bumped into a bunch of observers from the future at critical junctures in history? It is unlikely to assume that they all managed to perfectly disguise themselves, without making any errors in the design of the clothes they wore, their accents, their vocabulary, etc. Another option is that time travel is possible, but it is used with the utmost care and tight control, due to all the dangers we discuss here.

On June 28, 2009, physicist Stephen Hawking carried out a scientific experiment which was meant to answer this question once and for all. He brought snacks, balloons and champagne and hosted a secret party for time travelers only – but sent out the invitations only on the next day. If no one showed up, he argued, that would be proof that time travel to the past is not possible. The invitees failed to arrive. “I sat and waited for a while, but nobody came,” he reported at the Seattle Science Festival in 2012.

Multiple time travelers also undermine the possibility of a fixed and consistent timeline, assuming that the past can indeed be changed. Imagine, for example, a nail-biting derby between the top clubs, Hapoel Jericho and Maccabi Jericho. Originally Maccabi won, so a Hapoel fan traveled back in time and managed to lead to his team’s victory. Maccabi fans would not give up and did the same. Soon, the whole stadium is filled with time travelers and paradoxes.

One way or round trip?

When considering travel, it is always continuous – from point A to point B, through all the points in between. Time travel should supposedly be the same: travelers get into their machine, push the button, and go from time A to time B, through all the times in between. But there’s a catch, if we are only travelling through time, then to the casual observer, the time machine continuously exists in the same space between the points in time. The result is that our journey is one-way and the time travelers will stay stuck in the future or the past because the machine itself will block the time-path back. And that is before we even start wondering how to even build this thing in the first place if it already exists in the place where we want to build it.

If that’s the case, then there’s no choice but to assume that there is some way to jump from time to time or place to place and materialize at the destination. How will our machine “know” to jump to an empty area, and to avoid materializing into a wall or a living creature unlucky enough to occupy that same spot? The passengers will undoubtedly need effective navigation and observation equipment to prevent unfortunate accidents at the point of entry.

Advanced time travel

In addition to the problems that time travel poses for anyone trying to keep the notion of cause and effect in order, time travelers may also face – or already have faced – other challenges from physics, even classical physics.

One issue you have to consider during time travel, and which science fiction writers usually prefer to ignore for convenience sake, is the question of arrival at the specified time destination and what would happen to us there.

It is usually assumed, with no good reason, that if someone is travelling through time, he or she will land in the same place, but at a different time – past or future. But this is where we hit a snag: the Earth rotates around the sun at a speed of 110,000 kph, and the Solar System itself is moving in its trajectory around the galaxy at a speed of 750,000 kph. If we time-travel for even a few seconds and stay in the same coordinates of space, we will probably find ourselves floating in outer space and perhaps even manage a quick glance around before we die. Our time machine will have to take into account this movement of the heavenly bodies and place us at exactly the right spot in space.

This alone may be resolved, since time travel, in any case, takes place between two points in the four-dimensional space-time continuum. According to the theory of general relativity, the theoretical foundation for time travel, space and time are a single physical entity, known as space-time. This entity can be bent and distorted – in fact gravity itself is an external manifestation of space-time distortion.

The Time Lord ,Doctor Who explains what “time” is exactly (Doctor Who, Season 3, Chapter 10: Blink).

Time travel would be possible if we could create a closed space-time loop, or if we could go from one point to another through a shortcut called a “Wormhole”. This would, in any case, not be just moving from one point in time to another, but would also include moving through space. Thus, from the outset, the journey is not only in time, but necessarily includes a destination point in space, which we will need to pre-program on our machine, of course .

In practice, the situation is more complicated – especially if we want to go into the distant past or distant future. The speed of the celestial bodies, and even the Earth’s shape and the structure of the continents, the seas, and mountains on the face of the Earth, change over the years. And because even a tiny deviation in our knowledge of the past can land us in the core of the Earth, in outer space or somewhere else that immediately reduces life expectancy to zero – time travel becomes a Russian roulette.

How to travel in time and stay alive

Let’s assume we coped with this problem and managed to get to the exact point in space-time that can sustain life. Careful – we’re not there yet; we still have to deal with momentum.

Momentum is a conserved quantity, which basically represents the potential of a body to continue moving at the speed and direction in which it is already travelling. If we were to jump out of a moving car (heaven forbid!), conservation of momentum is what would cause us to roll on the ground and probably get injured (in the best-case scenario). And so, if we leap in time – say, a month back – and land at the exact same point on Earth – we would discover, much to our dismay, that even if we started motionless in relation to the ground, now the ground underneath us is moving quickly at one angle or another towards us . Thus, even if we were lucky enough not to crash immediately on impact, we’re likely to hit some obstacle. And if by some miracle we were to survive, we would quickly find ourselves burning up in the atmosphere or gasping for air in space – because we have far exceeded the escape velocity from Earth.

A possible solution to this problem is to plan our landing point ahead, so that the ground speed will be equal in size and direction to our exit speed, but this places many constraints on our journey. We could always leap into space, where there are hardly any moving objects to be bumped into, and only then land again at our point of destination on Earth.

Having said all that, this problem arises chiefly when we assume that time hopping is immediate – that we disappear from one point in time and immediately appear in another, without losing mass, energy, or momentum. But since a “realistic” journey in time is not instantaneous, rather it involves travelling along space-time, it is no different from other types of journeys. This being the case, we can hope that we could adjust our speed to the desired value and direction prior to landing, just like a spacecraft slowing down before landing on a planet.

We should also keep in mind that thankfully, we will have access to a powerful technology that would enable us to cope with such problems: Time-travel technology itself. For example, we might decide to send thousands of tiny probes ahead of us, each to a slightly different point in space-time. Some of them, maybe even most, will be destroyed for one of the reasons already mentioned. The others will wait patiently until the present and then feed their programmed coordinates into the time machine. Thus by definition, the destination entered will be safe for us, except, perhaps for the annoying probe shower hitting the travellers. For the travellers themselves, the entire process will be immediate.

Time Travelling Grammar

Finally, we come to the question: How do you actually talk about time travel? The three tenses – past, present, and future – are insufficient to discuss a future event that happened some time in the past with someone who is in the present, which is another’s past and yet another’s future. And what is the correct grammatical tense to use when we talk about an alternative future that would have been created after we killed our grandfather? Or how do we express the future-past tense (or past-future, or past-future-past?), when we get stuck in a time loop where what will happen leads to what had already taken place, and so on? And of course the biggest question that Hebrew editors and translators have faced for years – is there really such a thing as present continuous?

It’s complicated.

Arguing about tenses and a time machine, The Big Bang Theory, Season 8, Episode 5, 2014

In his book, The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, science fiction writer Douglas Adams suggests to his readers to consult (by Dr. Dan Streetmentioner) Time Traveler's Handbook of 1001 Tense Formations (by Dr. Dan Streetmentioner) to find the answers to these questions. That’s all very well, but, Adams tells us, “most readers get as far as the Future Semi-Conditionally Modified Subinverted Plagal Past Subjunctive Intentional before giving up; and in fact in later editions of the book all pages beyond this point have been left blank to save on printing costs.”

If, despite all of the above, you’re still intent on travelling back to Mount Sinai or the Apollo 11 moon landing – let us then wish you bon voyage, and please give our regards to Neil Armstrong!

Unlocking Time Travel Paradoxes: Your Ultimate Guide

Understanding the paradoxes of time travel is complex; this comprehensive guide provides exact and concise explanations. Time travel has been a popular concept in science fiction for many years, from h.g.

Wells’ “the time machine” to the recent “avengers: endgame” movie. However, the paradoxes that arise from changing time can be difficult to comprehend. This guide delves into the potential consequences of altering the past, present, and future, and the conflicting theories surrounding each scenario.

Through the use of real-world examples and theoretical explanations, this guide provides a clear understanding of the complicated topic of time travel paradoxes.

Credit: www.kobo.com

What Are Time Travel Paradoxes And Why Do They Matter?

Definition of time travel paradoxes.

Time travel paradoxes relate to logical puzzles that arise due to the possibility of travelling through time. These paradoxes or contradictions emerge because time travel to the past provides the option of changing events that have already occurred, thus creating a paradoxical timeline where the past causes the present, while the present modifies the future.

Time travel paradoxes can be divided into two categories: ontological paradoxes and causal loops. Ontological paradoxes result from a circumstance that makes it impossible to determine cause and effect, leading to a time loop, while causal loops happen when an event in the present or the future leads to a past event that has already occurred.

Here are some examples of the most popular time travel paradoxes:

Importance Of Understanding Time Travel Paradoxes

Comprehending the concept of time travel paradoxes is essential because it helps to avoid inconsistencies and illogical events in science fiction stories, movies, and books that involve time travel. While time travel is still theoretically unfeasible, knowing the paradoxes aids in making constructive and logical arguments that preserve story continuity and enhance readers’ overall experience.

Understanding time travel paradoxes also helps us in comprehending the physical realism behind these theoretical concepts, which inform our understanding of time. In addition, it helps one predict possible outcomes of time travel scenarios.

Examples Of Time Travel Paradoxes

Some of the most famous time travel paradoxes examples include:

- The grandfather paradox: Where a time traveler goes back in time and unintentionally kills their grandfather, preventing their birth and creating a paradoxical timeline.

- The bootstrap paradox: Where an object or information is perpetually circulated through time without any discernible origin.

- The predestination paradox: Where events from the future lead to the same events in the past, making it impossible to differentiate between cause and effect.

These paradoxes give rise to a plethora of logical puzzles and offer an in-depth understanding of the intricate structure of time travel.

The Grandfather Paradox: A Classic Conundrum

Time travel is a concept that has fascinated humans for centuries. Who wouldn’t love to go back in time and see their ancestors or the significant historical events they learned about in school? However, the idea raises many questions, including the paradoxes of time travel.

The grandfather paradox is among the best-known time travel paradoxes, and it goes something like this:

Explanation Of The Paradox

What if you had a chance to go back in time and kill your grandfather while he was still a young man? In this instance, if your grandfather dies before your mother or father was born, then how could you be alive today, let alone travel back in time, to begin with?

This is the paradox at play here. The paradox sets up a closed loop of causality where the outcome is either impossible or doesn’t make logical sense.

Different Interpretations Of The Paradox

People have proposed many ways to explain the paradox, but each raises more questions than it creates. For instance:

- One interpretation suggests that the past is not unique and that changing it would create a branching reality with a new timeline. However, this idea rarely explains how time travel affects the original timeline.

- Another interpretation suggests that a person traveling to the past cannot change what has already occurred; instead, their actions help to cause what has already happened in history. However, this interpretation raises an issue regarding free will.

Resolving The Grandfather Paradox

Several solutions have been proposed to resolve the paradox. Here are some of them:

- The novikov self-consistency principle states that the act of time travel is impossible in situations where it would lead to inconsistencies. In simpler terms, if an action would create a time paradox, it simply cannot happen.

- Another proposed solution is that time travelers who undertake the grandfather paradox cannot succeed in killing their ancestors, no matter how hard they try. The universe would magically conspire against them to prevent such an impossibility.

- Lastly, some theorists suggest that the paradox is, in fact, a theoretical problem rather than a practical one, and that it may never arise in any practical scenario.

The grandfather paradox is an enigmatic phenomenon that has defied a straightforward explanation. While several suggestions have been made to resolve the paradox, each explanation raises fresh questions or falls short of fully explaining time travel. Nonetheless, the paradox provides a delightful theoretical puzzle for those interested in the intricacies of spacetime.

Wormhole Time Travel: A Gateway To The Alternate Realities

Understanding the concept of wormhole time travel.

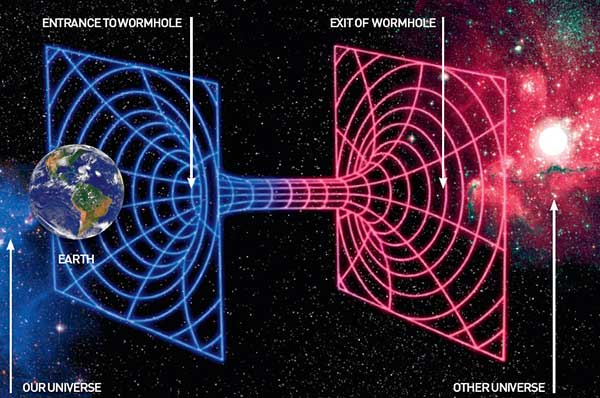

Wormhole time travel is a hypothetical method of traveling through time that involves using a wormhole, or a tunnel connecting two separate points in space-time. Here are the key points to understand about this concept:

- Wormholes are predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity and have been explored in science fiction for decades.

- The idea behind wormhole time travel is that if two wormholes were ever connected, one end could be used as a time machine to travel back or forward in time.

- However, the existence and stability of wormholes remain unproven, and creating a stable wormhole large enough to send a person through is purely theoretical at this point.

Theoretical Mechanics Of Wormhole Time Travel

The mechanics of wormhole time travel are complex and impossible to confirm without experimental evidence, but here are some of the key theoretical ideas:

- Wormholes are believed to be formed by warping space-time, creating a shortcut through the universe.

- In order to travel through a wormhole, it would have to be stabilized and kept open. The energy requirements for this would be astronomical.

- Time travel through a wormhole could potentially involve traveling faster than the speed of light, which violates current laws of physics and presents additional theoretical problems.

Potential Risks And Benefits Of Wormhole Time Travel

If wormhole time travel were ever made possible, it would undoubtedly come with risks and benefits. Here are a few potential examples:

- Benefits: Wormhole time travel could potentially allow people to explore other time periods and learn from history in ways that would otherwise be impossible. It could also lead to breakthroughs in physics and advance our understanding of the universe.

- Risks: Any form of time travel carries the risk of altering the timeline, creating paradoxes, or unintentionally causing harm to the future or past. Furthermore, the technology required for wormhole time travel would likely be exploited by governments, corporations, or individuals for malicious purposes.

While wormhole time travel remains purely hypothetical at this point, understanding its potential mechanics and implications is an important step in exploring the mysteries of time travel.

Time Travel In Literature And Film: A Brief History

Time travel is one of the most intriguing and fascinating concepts to grace the world of literature, film, and television. From the works of h. g. Wells and mark twain to modern-day film franchises like ‘Back to the Future’ and ‘Terminator’, time travel has been a widely discussed and debated phenomenon.

Here is a brief look at the history of time travel in literature, film, and television.

The Early Days Of Time Travel Fiction

- H.g. Wells’ groundbreaking novel, ‘the time machine’, introduced the concept of time travel to the world in 1895.

- Mark Twain’s ‘a connecticut yankee in king Arthur’s court’ explored the possibility of time travel in a light-hearted, satirical manner in 1889.

- In ‘the chronic argonauts’, published in 1888, welsh author d. d. home introduced the concept of a machine that could travel through time.

Evolution Of Time Travel In Cinema

- The earliest onscreen depictions of time travel can be traced back to the silent era of cinema, with films like ‘a trip to the moon’ (1902) and ‘the electric hotel’ (1908).

- The 1960 adaptation of h.g. Wells’ ‘the time machine’ introduced the modern concept of time travel on the big screen.

- The ‘back to the future’ trilogy, which premiered in the 1980s, is regarded as one of the most iconic and influential time travel movie franchises of all time.

Popular Time Travel Themes In Tv And Literature

- The concept of altering history and changing the present by traveling back in time is a widely explored theme in time travel literature and film.

- The ‘butterfly effect’ is a popular concept in time travel stories and refers to small, seemingly insignificant events in the past having dramatic consequences in the present.

- Time loops are another popular theme in time travel stories. The idea of reliving the same day or moment repeatedly has been explored in various films and tv shows, such as ‘groundhog day’ and ‘Russian doll’.

Overall, time travel remains a fascinating and captivating concept, with seemingly endless possibilities for exploration in literature, film, and television.

Time Travel In Science Fiction: Exploring The Possibilities

The science fiction universes of time travel.

The concept of time travel is a popular theme in science fiction. Here are the key points to understand the science fiction universes of time travel:

- Time travel has been portrayed in science fiction in various ways, including teleportation, time machines, and portals.

- Popular science fiction universes of time travel include a doctor who, back to the future, and the terminator.

- Doctor who is a british science fiction television series that features the adventures of a time-traveling alien called the doctor.

- Back to the Future is an American science fiction comedy film about a teenager who travels through time with the help of a delorean time machine.

- The terminator is a science fiction film franchise about a cyborg assassin sent back in time to eliminate the mother of the future resistance leader.

Impact Of Time Travel Fiction On Science And Technology

Science fiction has influenced scientific research and development in many ways, including in time travel. Here are the key points to understand the impact of time travel fiction on science and technology:

- Theoretical physicists have been inspired by science fiction to investigate the possibility of time travel using concepts such as black holes, wormholes, and spacetime.

- Science fiction has also influenced the development of technology, such as smartphones, virtual reality, and artificial intelligence, which were once considered far-fetched ideas from science fiction.

- Time travel fiction has also inspired the development of various tools and gadgets, such as the time-turner in harry potter and sonic screwdrivers in doctor who.

Real-Life Applications Of Time Travel Concept

The concept of time travel may seem like a purely fictional idea, but there are a few real-life applications of this concept. Here are the key points to understanding real-life applications of time travel:

- Time dilation is a real phenomenon predicted by Einstein’s theory of relativity, where time moves slower for objects that are moving faster or are in a stronger gravitational field.

- One application of time dilation is in satellite navigation systems, where accurate timekeeping is essential. The difference in the passage of time between the satellites and the receiver on Earth must be taken into account for accurate navigation.

- Time travel has also been proposed as a possible solution to prevent catastrophic events such as asteroid impacts or supernovas. By changing the trajectory of an object early enough, it may be possible to prevent it from colliding with Earth in the future.

The Bootstrap Paradox: The Self-Perpetuating Conundrum

Understanding the bootstrap paradox.

The bootstrap paradox is a mind-bending paradox that creates a self-perpetuating conundrum. It details a scenario where an item or information exists at a specific point in time without an origin. This paradox is also known as the ontological paradox and is a common trope in science fiction.

It arises because time travel creates a closed loop that defies the laws of causality. Some key features of the bootstrap paradox are:

- Information or object exists with no origin.

- The origin of the object is unknown as it has been passed from one instance of time to another.

- The object or information is self-created and self-maintaining.

Resolving The Bootstrap Paradox

The bootstrap paradox remains a paradox, and scientists do not have an explanation for it as it defies the laws of causality. However, there are ways to resolve it by creating multiple realities and timelines. Some ways to resolve this paradox are:

- Multiverse theory: This hypothesis suggests that there are multiple parallel universes, each following a different timeline.

- Fate vs. free will: This debate suggests that the information and objects that appear in the timeline appeared because they were fated to do so.

- Multiple time loops: Some theories suggest that bootstrap paradoxes can be resolved by creating multiple time loops. The origin of the object can be traced back to a different loop.

Examples Of The Bootstrap Paradox In Pop Culture

The bootstrap paradox has been a plot device in many fiction stories, movies, and tv shows. The following are some of the most popular examples of the bootstrap paradox in pop culture:

- Back to the Future (1985): Marty mcfly goes back in time and gives his younger self a sports almanac from the future. That younger self then gives the almanac to biff, who then becomes rich and powerful.

- Terminator (1984): In this movie, john connor sends kyle reese back in time to protect his mother from the Terminator. However, kyle reese turns out to be john’s father.

- Predestination (2014): This movie explores the bootstrap paradox when a time traveler becomes his mother and father.

The bootstrap paradox remains an enigma in science and has been a popular theme in science fiction. Although physicists have not yet found an explanation for it, it has produced some thought-provoking and entertaining stories in pop culture.

The Predestination Paradox: Past, Present, And Future Intertwined

Understanding the paradoxes of time travel: a comprehensive guide.

Time travel is a fascinating concept that never fails to pique our interest. However, as exciting as it may sound, it also presents a unique set of challenges one must face to fully comprehend the idea. One of the most intriguing paradoxes of time travel is the predestination paradox.

It is the notion that the past, present and future are interwoven, with each event depending on the other. In this segment of the guide, we will go through the explanation of the predestination paradox, different interpretations and ways to overcome it.

Explanation Of The Predestination Paradox

The predestination paradox states that if one travels back in time and changes something, that change may have already happened in the past. This means that the events of the past have already happened, and any attempt to change them might instead execute them.

In simpler terms, it means that the future creates the past, and the past creates the future. Here are some key points to keep in mind:

- Time travelers that attempt to change the past could unwittingly bring about the events they tried to prevent. This is often referred to as the ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’.

- On the contrary, any changes made in the past might have already happened.

- This means that the future might not be affected by any alterations made in the past, since they were part of the timeline already.

There are several interpretations of the predestination paradox. Here are a few of them:

- The novikov self-consistency principle suggests that the timeline is unchangeable because time travelers were always part of the timeline and have influenced events before they travel into the past.

- The multiple-worlds theory suggests that every alteration creates a new timeline. This means that the traveler will enter a different timeline where their actions will have different ramifications.

- The causality loop theory suggests that time travelers went back in time and did something they had to do, which resulted in the eventual outcome.

Ways To Overcome The Predestination Paradox

Overcoming the predestination paradox is challenging, but not impossible. Here are some ways to go about it:

- One way is to use a different model of time travel. For instance, ‘branching parallel universes’ is an alternate idea that proposes every time travel event leads to a new timeline, meaning changes to the past don’t affect the original timeline.

- Another way is to introduce the ‘memory cloud theory,’ which suggests that a time traveler’s memory of a particular event does not match the historical record since they have come from a different timeline.

The predestination paradox is a popular and paradoxical element of time travel. Although the concept can be challenging to grasp, different interpretations and techniques explain its mechanisms and how it can be overcome.

Implications Of Time Travel Paradoxes

Time travel is a concept that has fascinated people for decades. The ability to travel through time and witness historical events has been depicted in movies, books, and tv shows. However, the concept of time travel is not so straightforward and brings with it a set of paradoxes.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the paradoxes of time travel and their implications. In this section, we will delve into the philosophical, ethical, and scientific limitations of time travel.

Philosophical Implications Of Time Travel

Time travel raises a number of philosophical questions that have puzzled scholars for years. Below are some of the key philosophical implications of time travel:

- Time travel can lead to the possibility of altering the past, which then raises questions about free will and determinism.

- It could cause a temporal paradox, such as the grandfather paradox where one travels back in time and accidentally causes the death of their grandfather, resulting in them never being born.

- Time travel could also lead to the question of whether different timelines exist as a result of different choices being made, resulting in a multiverse.

Ethical Implications Of Time Travel

Time travel can have significant ethical implications that are worth considering. Below are some of the key ethical implications of time travel:

- Changing historical events could have a significant impact on the world we know today, resulting in unknown consequences.

- Time travel raises moral issues concerning the rights of individuals in the past. For instance, should one be allowed to interfere in a situation that happened in the past?

- Visiting the past may lead to ethical problems, for example, when one sees a disturbing event unfold and wants to prevent it from happening.

Scientific Limitations Of Time Travel

While time travel is a fascinating concept, science has its limitations, and these should be considered when thinking about the possibilities of time travel. Below are some of the key scientific limitations of time travel:

- Current scientific knowledge limits the possibility of backward time travel to levels that may not be noticeable, while forward time travel is plausible.

- Time travel to the past, if possible, may be limited to observations only, with no possibility of interacting with the environment.

- There are certain physical limitations that may make it impossible to travel through time, such as faster-than-light travel.

Time travel paradoxes raise many philosophical, ethical, and scientific questions. It is important to consider all of these implications before traveling through time and interfering with the course of history.

Frequently Asked Questions On Understanding The Paradoxes Of Time Travel: A Comprehensive Guide

What are the paradoxes of time travel.

Paradoxes of time travel are causality, predestination, and grandfather paradoxes which are contradictions.

Is Time Travel Possible According To Science?

According to science, some theories suggest time travel is possible but it remains unproven.

Can The Grandfather Paradox Be Solved?

The grandfather paradox has no known solution. Many theories and hypotheses suggest various resolutions.

As we come to the end of our comprehensive guide, it’s clear that time travel is not just a topic for science fiction. The paradoxes of time travel are complex and varied, and our understanding of them is constantly evolving.

One thing is certain – the more we study time travel, the more we realize how little we understand. Nevertheless, the important thing is to approach time travel theories with an open mind and a love for learning. Regardless of whether time travel ever becomes a reality, exploring the intricacies of such a concept is both fascinating and thought-provoking.

It forces us to consider our notions of causality, determinism, and free will, and it helps us better understand the fundamental nature of time and space. So, keep exploring, keep questioning, and who knows, maybe someday we’ll be able to take that leap through time.

Passport Specialist, Tech fanatic, Future explorer

Securing Your Business: Empowering Employees to Prevent Data Breaches

The ethics of ai companions: navigating rights, privacy, and interpersonal boundaries, leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Engineers Garage

Time Travel: Theories, Possibilities, and Paradoxes Explained

By Neha Rastogi February 16, 2017

Time Travel has been a matter of great interest for Science fiction since ages. Whether it’s the movies like Planet of the Apes (1968) or modern franchises like “Doctor Who” and “Star Trek” ; the concept is grabbing a lot of eyeballs. Not only movies and shows but even some mythological tales like Mahabharata and the Japanese story of Urashima Taro support the evidence that time travel exists. We often see stories where characters use time machines to jaunt through the years but the reality is far more complex and inexplicable.

Understanding the Concept of Time Travel

Time Travel is defined as the phenomenon of moving between different points in time through a hypothetical device called “Time Machine”. Despite being predominantly related to the field of philosophy and fiction, it’s somehow supported to a small extent by physics in conjunction with quantum mechanics. However, before getting into the argument of how real it is, let’s comprehend the fundamental meaning of time.

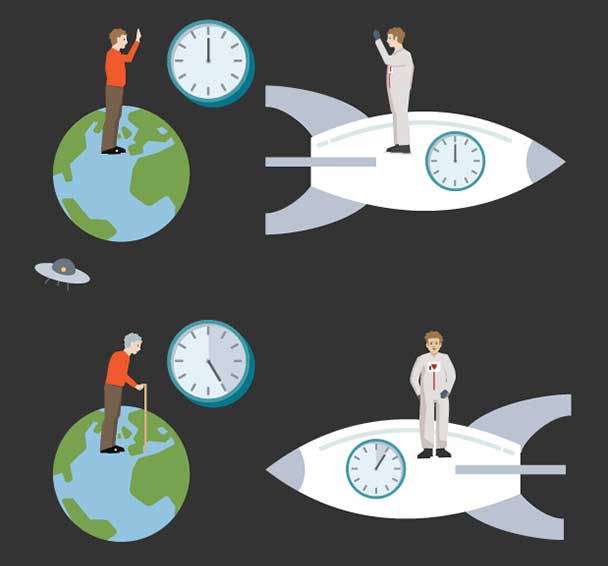

Basically, the whole idea of Time Travel is administered by the concept of time. Usually, people believe that time is constant but the famous Physicist Albert Einstein introduced the “Theory of Relativity” as per which, time is relative. In other words, time slows down or speeds up depending on how fast the observer moves relative to something else. According to him, a person traveling inside a spaceship at the speed of light would age much slower than his/her twin back at home.

Time is Relative

After Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, his teacher Herman Minkowski emphasized on space-time, a mathematical model that joins both space and time in a continuum. This implies that time and space cannot exist without each other. Space is a 3-dimensional arena consisting of length, width, and height. This is joined by Time with the fourth dimension called direction. So anything that happens in the universe takes place in this space-time continuum. Although this validates that space travelers are slightly younger than their twins when they return to earth, yet a huge leap in the past or future is not possible with the current technology.

Time Machines

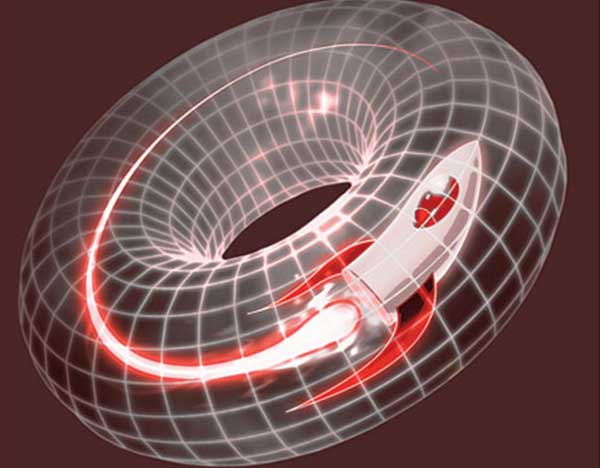

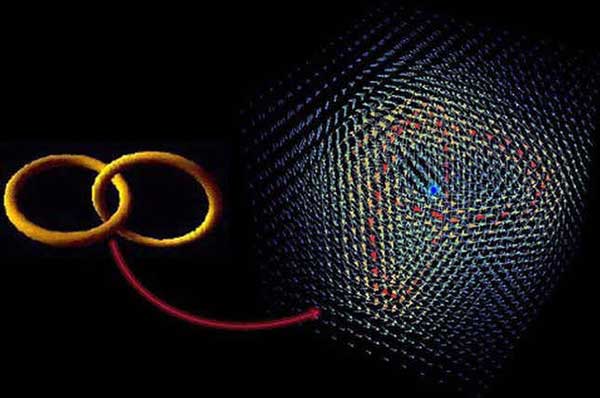

It is believed that in order to travel back or forward in time, one would require a device called Time Machine . The research on such a device would involve bending space-time to such an extent that time lines turn back on themselves to form a loop, which is termed as “closed time-like curve.” Such an action demands the use of an exotic form of matter with “negative energy density” that has a unique property of moving in the opposite direction of the normal matter when pushed. Even if it exists, the quantity would be too small to construct a machine.

Pictorial Representation of Time Travel through closed time-like curve

However, some another research suggests that time machines can also be constructed by building a doughnut-shaped hole enveloped within a sphere of normal matter. Inside this doughnut-shaped hole filled with vacuum, gravitational force can be used to bend the space-time so as to form a closed time-like curve. After racing around inside this doughnut a traveler would be able to go back in time with each lap. But in reality, it’s quite complex because the gravitational fields have to be very strong and would demand precise manipulation.

Time Travel Approaches in Physics

After studying and researching about Time Travel, various physicists have come up with approaches that may support its possibility, at least theoretically. Let’s take a look at these concepts so as to understand how Time Travel could actually work someday.

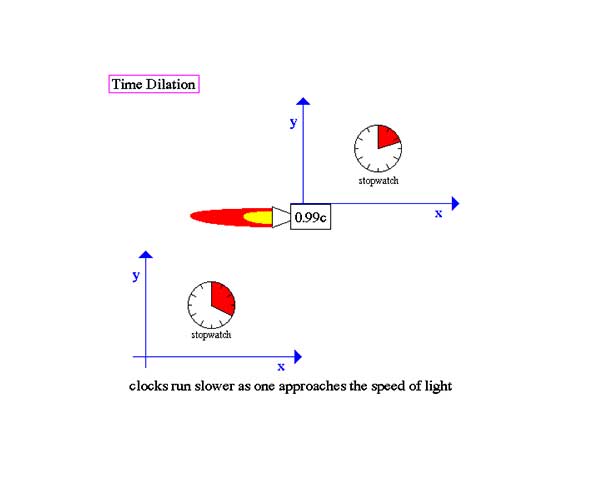

Time Dilation

Time Dilation Explanation

An important aspect of Einstein’s relativity theory is the term “time dilation” , which is defined as the difference of elapsed time between two events as measured by observers who are either moving relative to each other or are situated at different locations from the gravitational mass. As per the theory, time dilation can be summarized as a phenomenon which occurs due to the difference in either gravity or relative velocity.

In special relativity the time dilation effect is reciprocal i.e. when two clocks are in motion with respect to each other, for both the observers, the other one will be time dilated or the other clock will move slower. However, in general relativity, an observer at the top of the tower will find the clock closer to the ground to be slower and the other observer would agree about the direction and magnitude of this difference.

Due to the concept of time dilation, the current human time travel record is held by Russian cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev . Owing to the high-speed (7.66 km/s) of ISS and the length of time spent in space, it is believed that the cosmonaut actually arrived 0.02 seconds in the future while returning to the earth.

Cosmic String

Diagram Depicting Cosmic Strings

In 1991 J Richard Gott gave the idea of Cosmic Strings , which are believed to be left over from the early cosmos. These are defined as string-like objects or narrow tubes of energy that are stretched across the entire length of the universe. Owing to the huge amount of mass and massive gravitational pull, it would allow objects attached to the Cosmic Strings to travel at the speed of light.

So if two strings are pulled close to each other or one of them is stretched near the black hole, it might warp space-time to such an extent that would lead to creating a closed time-like curve and hence leading to the possibility of time travel. Theoretically, the gravity generated by these two Cosmic strings would help in propelling a spaceship into the past.

However, coming to the reality, the loop of strings is required to contain half the mass-energy of an entire galaxy so as to travel one year back in time. This implies that powering a time machine would require splitting half the atoms present in the whole galaxy.

Black holes

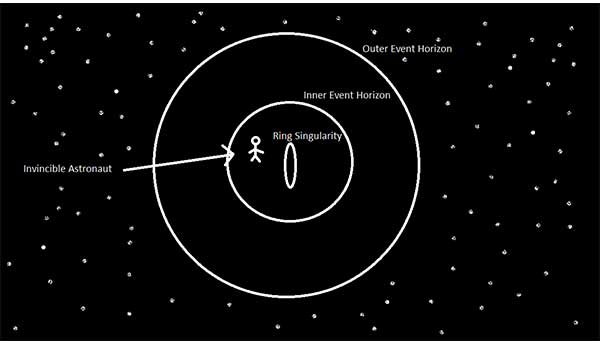

Illustration of Kerr Hole

When stars (having a mass of more than four times our sun) reach their end of life and all their fuel is burned up, they collapse under the pressure of their own weight creating “Black Holes” . The boundary of a Black Hole, called Event Horizon , has such a strong gravitational pull that it doesn’t even allow light to pass through it. Since light travels at the fastest speed, everything else traveling through a black hole is also dragged back. Such a non-rotating black hole is named as Schwarzschild black hole .

However, traveling to a parallel universe is possible through a rotating black hole named Kerr Hole . It was proposed in 1963 by a mathematician named Roy Kerr . As per his theory, if dying stars collapse into a rotating ring of neutron stars, that would produce enough centrifugal force to prevent the formation of singularity.

Note: Singularity can be perceived as the point into which the black hole tapers much like an ice-cream cone. At this point, the laws of Physics cease to exist and all the matter is crushed beyond recognition.

Since there will be no singularity, it would be safe to pass through a black hole without being crushed and exit out of a “White Hole” . A white hole is believed to be the exhaust end of a black hole which pushes everything away from it. Hence we may travel into another time or even another universe.

Although Kerr Holes are just theoretical, if they exist then we may find our way to a one-way trip to the past or future. However, physicist Kip Thorne believes that such a black hole doesn’t exist and it would suck everything before someone even reaches the Singularity.

Diagrammatic Representation of Wormhole

Wormholes, also known as Einstein-Rosen Bridges , are believed to be the most potential means for time travel. It could allow us to travel several light years from earth and in much less time as compared to the conventional space travel methods. The possibility of wormholes is based on Einstein’s theory of relativity which says that any mass curves space-time. The following example is used to explain this curvature.

If two persons are holding a bed sheet stretching it tight and a baseball is placed on the sheet, its weight will make it roll to the middle of the sheet creating a curve at that point. Now if a marble is placed on the sheet, it would travel towards the baseball because of the curve. Here space is depicted as a two-dimensional plane than the four dimensions that actually makes up space-time.

Now if this sheet is folded over leaving a space at the top and bottom, placing the baseball on the top would form a curvature. If an equal mass is placed at the bottom part at a point corresponding to the location of the baseball, the second mass would eventually meet with the baseball. Similarly, wormholes might develop.

In space, masses that place pressure on different parts of the universe combine together to form a tunnel. Theoretically, this tunnel joins two separate times and allows passage between them. However, it’s possible that certain unforeseen physical properties may prevent the occurrence of wormholes and even if they exist, these might be really unstable.

Possibly someday human may learn to capture, stabilize and enlarge these tunnels but according to Dr. Hawking, prolonging the life of a tunnel through folded space-time may lead to a radiation feedback loop destroying the time tunnel.

Time Travel Paradoxes

If we ever work out a theory for time travel, we would give way to certain complexities known as paradoxes. A paradox is something that contradicts itself. In other words, time travel is not believed to be a practical concept because of certain situations that are likely to arise as the after-effects. These are broadly classified as -:

1. Closed Casual Loops: The cause and effect run in a circle causing a loop and is also internally consistent with the timeline’s history.

Diagram depicting time loop

• Predestination Paradox

It is defined as a situation when a traveler going back in time causes the event which he is trying to prevent from happening. It implies that any attempt to stop any event from occurring in the past would simply lead to the cause itself. The paradox suggests that things are destined to turn out the way they have happened and anyone attempting to change the past would find himself trapped in the repeating loop of time. For example, if you travel in the past to prevent your lover from dying in a road accident, you will find out that you were the one who accidentally ran over her.

• Bootstrap Paradox

A bootstrap paradox, also known as an Ontological Paradox where an object, person, or piece of information sent back in time leads to an infinite loop where the object has no discernible origin and is believed to exist without ever being created. It implies that the past, present and future and not defined, thus making it complicated to pinpoint the origin of anything. It raises questions like how were the objects created and by whom.

2. Consistency Paradox: It generates a number of timeline inconsistencies related to the possibility of altering the past. It can be further divided into the following categories.

• The Grandfather Paradox

Grandfather Paradox

This paradox talks about a hypothetical situation where a person travels back in time and kills his paternal grandfather at the time when his grandfather didn’t even meet his grandmother. In such a situation, his father would never have been born and neither would the traveler himself. So if he was never born, how would he travel to the past to kill his grandfather?

The paradox also talks about auto-infanticide where a time traveler goes into the past to kill himself when he was an infant. Now if he killed himself when he was a kid, how would he exist in the future to come back in time? Some physicists say that you would be able to go back in time but you won’t be able to change it, while others suggest that you would be born in one universe but unborn in another universe.

• The Hitler Paradox

Similar to the grandfather paradox, the killing Hitler paradox erases the reason for which you would want to go into the past and kill Hitler. Moreover, killing grandfather might have a “butterfly effect” but killing Hitler would have a far-reaching impact on the History as it would change the whole course of events. If you were successful in killing Hitler, there’d be no reason that would make you want to go back in time and kill him.

This paradox has been explained very well in a Twilight Zone episode called “Cradle of Darkness” as well as an episode “Let’s Kill Her” from Dr. Who.

• Polchinski’s Paradox

American physicist Joseph Polchinski proposed a paradox where a billiard ball enters a wormhole and emerges out of the other end in the past just in time to collide with its younger version and prevents it from entering the wormhole in the first place. While proposing this scenario, Joseph had Novikov’s Self Consistency Principle in his mind which states that time travel is possible but time paradoxes are forbidden.

A number of solutions have been suggested to avoid these inconsistencies like the billiard ball will deliver a blow which changes the course of the younger version of the ball but it would not stop it from entering the wormhole. This also explains that if you go back in time to kill your grandfather then something or the other will happen to prevent you from making it happen thus preserving the consistency of the History.

Solutions for the Paradoxes

In order to come up with a solution for these above-mentioned paradoxes, scientists have proposed some explanations which are enlisted below

The Solution: Time Travel is impossible because of the paradoxes that it creates.

Self-Healing Hypothesis: If we succeed to change the events in the past, it will set off another set of events that will keep the present unchanged.

The Multiverse: Every time an event in the past is altered, an alternate parallel universe or timeline is created.

Erased Timeline Hypothesis: A person traveling to the past would exist in the new timeline but their own timeline would be erased.

Is Time Travel Possible?

Nobody seems to have a definite answer in support or against the existence of Time Travel. On one hand, Einstein suggested to traveling at the speed of light in order to jaunt through the future but this would mean an unimaginable amount of energy would be required. Moreover, the centrifugal force on the body would prove to be fatal. Although it has been observed that space travelers age a little slower as compared to their identical twin on earth but some believe that there is no definite answer to travel back in space.

Theoretical physicist Brian Greene of Columbia University says that “No one has given a definite proof that you can’t travel to the past. But every time we look at the proposals and detail it seems kind of clear that they’re right at the edge of the known laws of physics.” Besides, Prof. Hawking feels that “Today’s science fiction is tomorrow’s science fact.”

However, the paradoxes, especially the grandfather paradox, have imposed a big question mark on the possibility of Time Travel. Basically, with the present laws and knowledge of Physics, the human won’t be able to survive in the process of Time Travel. So, we need certain developments in the quantum theories till we are sure as to how the paradoxes can be solved.

You may read our Blog and Article section for more topics on electronics engineering, industry, and technology.

Questions related to this article? 👉Ask and discuss on Electro-Tech-Online.com and EDAboard.com forums. Tell Us What You Think!! Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Search Engineers Garage

- Arduino Projects with code and circuit diagram

- Raspberry pi

- 8051 Microcontroller

- PIC Microcontroller

- Battery Management

- Electric Vehicles

- EMI/EMC/RFI

- Hardware Filters

- IoT tutorials

- Power Tutorials

- Circuit Design

- Project Videos

- Tech Articles

- Invention Stories

- Electronic Product News

- Business News

- Company/Start-up News

- DIY Reviews

- EDABoard.com

- Electro-Tech-Online

- EG Forum Archive

- Cables, Wires

- Connectors, Interconnect

- Electromechanical

- Embedded Computers

- Enclosures, Hardware, Office

- Integrated Circuits (ICs)

- LED/Optoelectronics

- Power, Circuit Protection

- Programmers

- RF, Wireless

- Semiconductors

- Sensors, Transducers

- Test Products

- eBooks/Tech Tips

- Design Guides

- Learning Center

- Webinars & Digital Events

- Digital Issues

- EE Training Days

- LEAP Awards

- Webinars / Digital Events

- White Papers

- Engineering Diversity & Inclusion

- Guest Post Guidelines

The Quirk E. Newsletter

We promise to send you only the coolest stuff we have to offer every month, like information on new releases, preorder campaigns, giveaways, and discounts. Right now, you only need 3 referrals to get a free e-book!

Or subscribe and set genre preferences

By clicking subscribe, I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Quirk Books’ Privacy Policy and Terms of Use . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Classic Time Travel Paradoxes (And How To Avoid Them)

[Movie still from Time Machine , Warner Bros. and Dreamworks]

Editor's Note: We're bringing back one of our most loved posts because hey, time travel is always a relevant topic of discussion. Originally published 11/30/12.

Author's Note: I assume that some day, this article will serve as an invaluable guide and warning for our time traveling ancestors-to-be (who will of course be unable to read books and learn these lessons for themselves, either because [a] all the books will have been burned, or [b] kids will have stopped reading books entirely, because grumble grumble, god damn kids, when I was your age, video games, blah blah, detriment to society, buncha hooligans, kids these days, no respect, etc). In the meantime, just enjoy it for all of its delightfully entertaining/convoluted/paradoxical pleasures.

As anyone who’s anyone who’s read any time travel story ever could easily tell you, time travel is a tricky subject. Temporal paradoxes might seem simple and straightforward at the start (no they don’t), but they always devolve quite quickly (linear time-wise) into some sort of trippy, philosophically complicated, timey-wimey conundrum that makes even the most convoluted middle school relationship make sense by comparison. Come to think of it, maybe the reason that all those cool kids in middle school suffer from impossibly complicated and melodramatic romances to begin with is because they’re all too “cool” to read time travel stories in the first place, which would obviously teach them the benefits of temporally linear dating, if nothing else.

I’m looking at you, River Song.

For the most part, any paradox related to time travel can generally be resolved or avoided by the Novikov self-consistency principle, which essentially asserts that for any scenario in which a paradox might arise, the probability of that event actually occurring is zero — or, to quote from LOST, “whatever happened, happened,” meaning that no matter what anyone does, they can’t actually create a paradox, because the laws of quantum physics will self-correct to avoid such a situation. Still, I’m wary of such a loose explanation for things, and so below, I’ve compiled a list of a few of the more popular time travel paradoxes — and what to do to avoid them.

ONTOLOGICAL PARADOX : Also known as the “Bootstraps Paradox,” an ontological paradox arises when a person or object is sent through time and recovered by another person, whose actions then lead to the original person or object back to the time from when it came in the first place, thus creating an endless loop with no discernible point of origin. Thus, the original person or object is essentially “pulling itself up by its own bootstraps,” hence the nickname (thanks in no small part to the Robert Heinlein story “By His Bootstraps”).

Example : The Terminator films are a prime and popular example of the Ontological Paradox. In the future, a Terminator is sent back in time to kill the mother of resistance leader John Connor before he is born. While the original T-800 is ultimately destroyed, the leftover pieces are found by scientists who use the technological to…develop and create Skynet, and the Terminator-series robots. Skynet would have never been created if Skynet hadn’t taken over the world and then sent a Terminator back in time to get destroyed and ultimately lead to the creation of Skynet. Trippy, right?

There's also the fact that Future John Connor sends his buddy Kyle Reese back in time to protect his mother from the T-800, only Kyle ends up totally bangin' John's mom (dude high five! I mean, not cool, man) and impregnates her with his buddy John Connor. So to top it all off, if John hadn't sent his friend back in time, his friend would never have had sex with John's mom, and John would never have been born (meaning that Kyle Reese is either the best or worst friend, ever).

How to Avoid : No one’s really sure if a real-life ontological paradox would lead to some massive hemorrhaging of spacetime, or if the closed loop is kind of automatically self-corrected since it all works itself out evenly in the end anyway. Still, better to avoid these kind of complicated situations, and the best way to do that would simply be to stop taking candy from strangers — “candy” in this case being mysterious or alien artifacts with questionable origins, possibly given to you by mysterious people who may or may not come from the future. See? Maybe all those warnings that your Mom gave you when you were a little kid still mean something today. Or maybe all along she was just trying to prevent you from sending your friends back in time to sleep with her. Or perhaps encourage it…

PREDESTINATION PARADOX : The predestination paradox is similar to the ontological paradox in that the Cause leads to an Effect which then leads back to the initial Cause. The basic tenant of the predestination paradox is similar to that of a self-fulfilling prophecy: the motivation for the time traveler to travel in time is ultimately realized to have been the time traveler’s fault, due to his or her decision to time travel in the first place, or else otherwise unavoidable. Stories involving predestination paradoxes often involve a heavy sense of irony — the time traveler might go back in time in order to change something, for example, but his or her actions inadvertently lead to the exact situation that inspired the time traveler to have gone back and changed things. Thus, nothing ultimately changes. Determinism is a bleak friend.

Example : In Twelve Monkeys, James Cole is sent back in time to prevent a mysterious disaster involving the “Army of the Twelve Monkeys.” His wild rantings in the past about the terrible future from which he came are overheard by Jeffrey Goines, a mental patient who is remembered in the future as the leader of Army of the Twelve Monkeys. Ultimately, Cole’s efforts to prevent his future from happening inspire the actions that lead to his future coming to be. And in a cruel twist of irony, James Cole’s childhood memory of a man in a airport being shot and falling into the arms of a beautiful blonde — the memory that haunts him for the rest of his life — turns out that the guy who was shot was actually him, in the future, dooming young James Cole to grow up and repeat the cycle all over again.

How to Avoid : This one’s tricky, because philosophically, it’s all about free will (or lack thereof). So in fact, by trying to teach you to how to avoid falling victim to the tenants of the predestination paradox, I’m probably going to inspire you to go back in time and create the French film La jetée, which in turn inspires Terry Gilliam to make Twelve Monkeys, which in turn inspires me to use it as an example in this article, et cetera et cetera. Basically we’re all screwed, unless we avoid time travel and time travelers all together. Even a many worlds theory/alternate timeline thing can’t prevent this, because your actions wouldn’t even create a divergent timeline — they would just result in your present situation. So, sorry dude, nothing you can do is going to change anything. Again, unless you don’t do anything at all, although that still doesn’t guarantee anything.

GRANDFATHER PARADOX : This one perfectly demonstrates the aforementioned Novikov self-consistency principle. The basic idea is that, no matter how hard you try, you can’t go back in time and kill your grandfather, because if you did, your mother or father would never have been born, which means that you would never have been born, which means you couldn’t have gone back in time and killed your grandfather, which means that you didn’t go back in time and kill your grandfather, because you can’t go back in time and kill your grandfather, because if you did, you wouldn’t be born, which you obviously have already been born because if you were never born then you couldn’t have gone back in time and tried (and failed) to kill your grandfather in the first place.

That’s just a simple and straightforward summary though. You know, in Layman’s terms.

Basically, the Grandfather paradox conveys the idea of a self-correcting universe and/or fixed points in time. Even if you were able to go back in time and, I don’t know, shoot your Grandpa in the head before he ever meets your Grandma (jeez, you must really hate that guy, huh?), your Grandfather would turn out to be an early sperm donor or something, who would still manage even posthumously to impregnate your Grandmother, because you would have to exist in order to have shot him in the head in the first place. So you might be able to fudge a few temporal details here and there, but no matter what you do, the end result stays the same.

Example : Let’s just say that when you're LOST on a magical tropical island somewhere in the Pacific Ocean (ish?) and you end up skipping through time and decide to try to kill that evil guy while he’s still a kid and/or stop a nuclear bomb you've so affectionately nicknamed “The Jughead” from exploding and causing all kinds of electromagnetic problems and inconsistencies on your already-mystical island home, the best that’s going to happen is you get some kind of weird Hindu sideways limbo reality that works as a parallel narrative to the entire last season of your television show. Oh, and that little kid you shot still turns out to be pretty evil, and it’s all your fault.

How to Avoid : Uhh, don’t try to kill your grandfather in the past before the birth of your father? Take that as a metaphor all you’d like.

HITLER'S MURDER PARADOX : This is similar to the Grandfather Paradox, in that the time traveller goes back in time to change something significant that has already happened. Unlike the Grandfather Paradox (which we assume would self-correct despite our best efforts), the change that one wishes to affect in the Hitler’s Murder Paradox is one that is more technically feasible — as in not intrinsically paradoxical — but still ultimately problematic.

The name comes from the idea that one could theoretically go back in time and kill Adolf Hitler before the Holocaust happened, thus preventing the systematic annihilation of some six million Jews and other minorities. Which, ya know, all sounds good and well, except that it tends to lead to some kind of downward spiraling domino effect with plenty of other consequences that the well-intentioned time traveler probably didn’t consider, and which ultimately might lead to a worse situation than that which the time traveler had hoped to prevent.

Example : This kind of stuff is rampant in comic books, especially X-Men, but the best example of it was the early 90s Age of Apocalypse storyline, in which Professor Xavier’s schizophrenic mutant son, Legion, decides to make daddy proud by helping his dream of mutant-human co-existence come true. Legion concludes that the best way to do this is to go back in time and kill Magneto before he becomes, ya know, Magneto. The only problem is, Magneto and Xavier were like totally BFF back then, so Xavier ends up taking the bullet for Magneto and dies (so yes, Legion does technically end up killing his own father, but that’s not the point).

As a result of there being no Charles Xavier, the psycho evil Darwinist uber-mutant Apocalypse ends up taking over the world before Magneto’s team of X-Men (named in honor of his deceased friend) are able to stop him, which leads to all kinds of crazy situations like evil Hank McCoy aka Dark Beast, who works alongside the evil versions of Cyclops and Havok, or a Sabretooth who is actually a pretty likeable superhero and a member of the X-Men. Oh, also, Magneto and Rogue totally have the sex, and humans are being systematically slaughtered in concentration camps by Apocalypse and his cronies. So basically, in his attempt to kill a perceived “Hitler” in the form of Magneto, Legion caused a real and even more twisted Holocaust to happen. WHOOPS.

How to Avoid : In addition to the whole alternate-reality-that-is-ironically-worse-than-the-world-as-it-used-to-be problem, there’s also the moral compromise of killing an innocent child, even though you know that child is going to grow up to become pretty much the worst (greatest?) mass murderer in history. The best way to avoid it is simply and sadly to accept that you cannot change the past and shouldn’t even try. That is, unless you’re smart enough to have eliminated any possibility of negative domino effect resulting out of your actions.

For example, if you went back in time and eliminated M. Night Shyamalan shortly before the release of Signs, there would be nothing but positive results; the world would mourn the tragic and mysterious loss of a gifted young filmmaker taken before his time, we would all be so blinded by the shock of his death that we’d be able to ignore how bad the aliens looked in that movie (and the fact that seeing them at all was completely unnecessary), and the rest of us wouldn’t have been forced to endure such awful schlock as The Happening or Lady in the Water. See? That way everyone wins!

BUTTERFLY EFFECT : Similar to the cascading domino effect of the Hitler’s Murder Paradox, but on a different level. Whereas killing Hitler would obviously be a landmark event with quite a significant historical impact, something like, say, accidentally stepping on a bug in the past probably wouldn’t have as big of an effect, right?

Have you even been paying attention? Of course it will! That’s the whole point of a time travel paradox! Just like the way that a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil can affect a weather system in Texas, one tiny change in the past can lead to all kinds of Rube Goldbergian complications that can subtly — or seriously — affect the present. The term “Butterfly Effect” is actually derived from “A Sound of Thunder,” a short story by Ray Bradbury, in which a character accidentally steps on a butterfly in prehistoric times and causes catastrophic changes in the future from which he came.

Example : In Orpheus With Clay Feet by Philip K. Dick, the main character, Jesse Slade, enlists in the services of a time travel tourism agency, who set him up with a trip that allows him to go back in time and act as a muse for some significant historical figure. Slade chooses to go back and inspire his favorite science fiction writer Jack Dowland (which was also Dick’s pen name). Unfortunately, in his efforts to inspire Dowland’s monumental science fiction work, Slade directly reveals to Dowland that he is a time traveler hoping to inspire his work. Dowland takes this as an insulting ruse, and as a result, never becomes the great science fiction writer that he is meant to be. He does, however, publish a single science short story, under the pen name Philip K. Dick: a story called Orpheus With Clay Feet, about a time traveler that goes back in time to inspire his favorite science fiction writer, a man named Jack Dowland.

How to Avoid : Watch your step

Like What You Just Read? We Suggest The Following Blog Posts.

Privacy Overview

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

Paradoxes of Time Travel

Ryan Wasserman, Paradoxes of Time Travel , Oxford University Press, 2018, 240pp., $60.00, ISBN 9780198793335.

Reviewed by John W. Carroll, North Carolina State

Wasserman's book fills a gap in the academic literature on time travel. The gap was hidden among the journal articles on time travel written by physicists for physicists, the popular books on time travel by physicists for the curious folk, the books on the history of time travel in science fiction intended for a range of scholarly audiences, and the journal articles on time travel written for and by metaphysicians and philosophers of science. There are metaphysics books on time that give some attention to time travel, but, as far as I know, this is the first book length work devoted to the topic of time travel by a metaphysician homed in on the most important metaphysical issues. Wasserman addresses these issues while still managing to include pertinent scientific discussion and enjoyable time-travel snippets from science fiction. The book is well organized and is suitable for good undergraduate metaphysics students, for philosophy graduate students, and for professional philosophers. It reads like a sophisticated and excellent textbook even though it includes many novel ideas.

The research Wasserman has done is impressive. It reminds the reader that time travel as a topic of metaphysics did not start with David Lewis (1976). Wasserman (p. 2 n 4) identifies Walter B. Pitkin's 1914 journal article as (probably) the first academic discussion of time travel. The article includes a description of what has come to be called the double-occupancy problem, a puzzle about spatial location and time machines that trace a continuous path through space. The same note also includes a lovely passage, which anticipates paradoxes about changing the past, from Enrique Gaspar's 1887 book:

We may unwrap time but we don't know how to nullify it. If today is a consequence of yesterday and we are living examples of the present, we cannot unless we destroy ourselves, wipe out a cause of which we are the actual effects.

These are just two of the many useful bits of Wasserman's research.

Chapter 1 usefully introduces examples of time travel and some examples one might think would involve time travel, but do not (e.g., changing time zones). There is good discussion of Lewis's definition of time travel as a discrepancy between personal and external time, including a brief passage (p. 13) from a previously unpublished letter from Lewis to Jonathan Bennett on whether freezing and thawing is time travel. I had often wonder what Lewis would have said; now I know what he did say!