What Is a Level 5 Emergency Room Visit, and Why Does It Cost So Much?

If you visit the emergency room, your bill will typically include a "ER visit level" line item that’s based on the complexity of your treatment. A Level 5 emergency room visit, or ER visit level 5, is reserved for the most severe cases.

Visit levels range from 1 to 5, from mild to most severe, and most ER visits fall around level 3 or level 4, explains Goodbill lead medical coder, Christine Fries.

A Level 5 emergency room visit charge is reserved for the most severe cases. Most visits fall around level 3 or 4.

Generally speaking, you’re billed for an ER visit level 4 if you get two or fewer diagnostic tests, which can include labs, EKGs or X-rays. Once you get three or more diagnostic tests, you’ll be billed for an ER visit level 5.

Read more ER visit levels here: Why Did My Emergency Room Visit Cost So Much?

But watch out: Hospitals sometimes inflate the leveling on your bill, also known as "upcoding," even if your visit didn’t meet the criteria for that level. The difference in cost between an ER visit level 4 and an ER visit level 5 can be thousands of dollars, she says.

ER visit levels are sometimes inflated on your bill, known as "upcoding." The difference in cost can be thousands of dollars.

"That’s probably the line we see most often stepped over, is they’re billing that ER visit level 5, when it just wasn’t there," Fries told patient advocacy nonprofit Healthcare Reformed in an interview. "With just a single line item flagged as upcoding between an ER visit level 4 and 5, we’ve saved patients over $2,000."

On your bill, a Level 5 emergency room visit charge may show up differently, depending on the hospital. Here are some common ways it might appear on your bill:

- Level 5 ED visit

- ER visit level 5 / ER visit lvl 5

- ED visit level 5 / ED visit lvl 5

To learn more, listen to Fries' full video interview below.

@christyprn Video quality is down📉, but educational quality is UP. 📈 #healthcare #healthcarereform #medicalbills #hospitalbill #medicaldebt #patientadvocate ♬ original sound - Christy, RN | Advocate

Guides, news, and articles to help you tackle hospital bills.

Why Do ER Visits Cost So Much?

Here are 5 things you need to know about ER visit costs, and how to tell if your bill is correct.

How to Negotiate Your Hospital Bill

Read our expert tips on how to negotiate your hospital bill to save up to thousands of dollars.

.jpg)

Can Hospital Bills Affect My Credit?

You have time before your bill can go to collections or affect your credit.

Building trust and confidence into every health care transaction.

© 2022 Goodbill, Inc.

2023 Documentation Guideline Changes for ED E/M Codes 99281-99285

On July 1, 2022, the American Medical Association (AMA) released a preview of the 2023 CPT Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management (E/M) services. These changes reflect a once-in-a-generation restructuring of the guidelines for choosing a level of emergency department (ED) E/M visit impacting roughly 85 percent of the relative value units (RVUs) for typical members. Since 1992, a visit level was based on a combination of history, physical exam, and medical decision-making elements. Beginning in 2023, the emergency department E/M services will be based only on medical decision making.

You Might Also Like

- Documentation Pearls for Navigating Abscess Incision/Drainage Codes

- ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes to Use for Zika Virus Documentation

- Avoid Patient History Documentation Errors in Medical Coding

Explore This Issue

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) represents the specialty in the AMA current procedural technology (CPT) and AMA/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee (RUC) processes. In fact, they are your only voice in those arenas. The AMA convened a joint CPT/RUC work group to refine the guidelines based on accepted guiding principles. Although the full CPT code set for 2023 has not yet been released, the AMA recognized that specialties needed to have access to the documentation guidelines changes early to educate both their physicians on what to document and their coders on how to extract the elements needed to determine the appropriate level of care based on chart documentation. Additionally, any electronic medical record or documentation template changes will need to be in place prior to January 1, 2023, to maintain efficient cash flows and ensure appropriate code assignment.

ACEP was able to convince the Joint CPT/RUC Workgroup that time should not be a descriptive element for choosing ED levels of service because emergency department services are typically provided on a variable intensity basis, often involving multiple encounters with several patients over an extended period of time. It would be nearly impossible to track accurate times spent on every patient under concurrent active management.

The prior requirements to document a complete history and physical examination will no longer be deciding factors in code selection in 2023, but instead the 2023 Guidelines simply require a medically appropriate history and physical exam. That leaves medical decision making as the sole factor for code selection going forward. These changes are illustrated by the 2023 ED E/M code descriptors, which will appear as follows:

The 2023 E/M definitions have been updated to reflect simply Medical Decision Making determining the level.

- 99281: ED visit for the evaluation and management of a patient that may not require the presence of a physician or other qualified health care professional.

- 99282: ED visit for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires a medically appropriate history and/or examination and straightforward medical decision making.

- 99283: ED visit for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires a medically appropriate history and/or examination and low medical decision making.

- 99284: ED visit for the evaluation and management of a patient which requires a medically appropriate history and/or examination and moderate medical decision making.

- 99285: ED visit for the evaluation and management of a patient, which requires a medically appropriate history and/or examination and high medical decision making.

Pages: 1 2 3 | Single Page

Topics: 2023 guidelines Coding CPT guidelines Practice Management Reimbursement & Coding

Uncovering Hidden ACEP Member Resource Gems

Medicare’s Reimbursement Updates for 2024

Workplace Violence and Mental Health in Emergency Medicine

Current issue.

ACEP Now: Vol 43 – No 06 – June 2024

Download PDF

No Responses to “2023 Documentation Guideline Changes for ED E/M Codes 99281-99285”

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Once you learn the rules, choosing the right code is easier than you think.

THOMAS A. WALLER, MD

Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14(1):21-25

Dr. Waller is an assistant professor of family medicine at Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and associate program director for the family medicine residency program at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. Author disclosure: nothing to disclose.

Careful and correct documentation and coding are vital skills for every family physician. They enable us to record the high-quality care we provide for our patients and help ensure that we don't undercode or overcode the services we provide.

My previous article, “Coding Level-IV Visits Without Fear” (FPM, February 2006) , focused on ensuring that you're coding all the level-IV visits you're entitled to. This article will focus on the slight differences in the requirements for established patient level-II (99212) and level-III (99213) visits – differences that can have a surprisingly significant effect on your bottom line if you don't understand them well. For example, the 2007 Medicare allowance (not adjusted for geographic differentials) for a 99212 is $37.14, while the allowance for a 99213 is $59.50. Consequently, each time you code a 99212 when you should have coded a 99213, you leave $22.36 on the table. If you undercode 10 of these visits a week, you've failed to capture $223.60 per week, or more than $10,700 over 48 weeks.

Of course, learning when a 99213 is really a 99212 is also important. Thorough documentation of the work you perform, along with careful attention to medical necessity, will help you audit-proof your practice.

History and exam

Medicare's Documentation Guidelines for Evaluation and Management Services , which most private payers also rely on to a great degree, divides documentation into three key components: history, exam and medical decision making. For established patient visits (99211-99215), two of the three key components must meet or exceed criteria to qualify for a specific level of evaluation and management (E/M) services. (This does not apply to new patient visits, 99201-99205, which require not only all three key components but also more detail for certain key components.)

The documentation guidelines are available in 1995 and 1997 versions, and we are allowed to use either one. Of note, the only significant difference between the two versions is the exam section. I prefer to use the 1995 guidelines, and I have used them in this article, because I believe the exam requirements are easier to follow. Here are the criteria to keep in mind when conducting a patient history and exam:

History. The history requirements for level-II and level-III visits are comparable. They both require that you note a chief complaint (CC) and one to three elements (location, quality, severity, duration, timing, context, modifying factors, or associated signs and symptoms) that describe the history of present illness (HPI). A past medical, family and social history (PFSH) is not required for either level-II or level-III visits.

The only difference between the history requirements for a level-II and a level-III visit is the review of systems (ROS). A level-II visit does not require an ROS, while a level-III visit requires a problem-pertinent ROS, which is a description of one system that is directly associated with the problem. This additional component raises the level of history from problem-focused to expanded problem-focused.

Exam. The exam requirements are slightly different for level-II and level-III visits. Under the 1995 guidelines, a level-II exam must be problem-focused, which requires the description of one component of the affected body area or organ system. A level-III exam is expanded problem-focused, which requires the description of one component of the affected body area or organ system and at least one other affected body area or organ system. The body areas include the following: head/face, neck, chest/breasts/axillae, abdomen/genitals/groin/buttocks, back/spine and each extremity. The organ systems include the following: constitutional (general appearance or vital signs); eyes/ears/nose/mouth/throat, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, skin, neurologic, psychiatric and hematologic/lymphatic/immunologic.

The 1997 guidelines require documentation of one to five specific exam “bullets” for level II and six to 11 bullets for level III. You can find a complete list of exam bullets, as well as the 1995 and 1997 guidelines in their entirety, on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services' Web site at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp .

Medical decision making

The medical decision making component represents the most significant difference between a level-II and a level-III visit. “Straightforward” decision making is sufficient for level II, while “low complexity” decision making is required for level III. Three parameters (diagnosis, data and risk) combine to determine the level of decision making. When two of the three parameters meet or exceed the specified requirements, then the overall level of decision making is determined.

You can use a simple point system to evaluate the number of possible diagnoses or management options and the amount of data to be evaluated. While the point system is not part of the documentation guidelines, it is widely used by Medicare carriers, coders and physicians to assess documentation and aid in code selection.

Diagnosis. The number of diagnoses or management options needed for a level-II visit is considered minimal; only one point is required. You can earn one point if the patient has a self-limited or minor problem (e.g., cold, insect bite, tinea corporis) or an established problem that is stable or improved.

The number of diagnoses or management options for a level-III visit is considered limited, with two points required. Two self-limited problems, two stable established problems or one established problem with mild exacerbation would each yield two points.

Data. In the data section, points are earned according to the amount and complexity of data to be ordered or reviewed. You should document your review of lab, radiology or other diagnostic tests. If you order, plan, schedule or perform a diagnostic service at the time of the encounter, you should document this as well.

For a level-II visit, you need one point to meet the data requirement, which is considered minimal. You can earn one point by ordering or reviewing lab, radiology or procedure reports, or simply by obtaining old records about the patient or obtaining history from someone other than the patient (e.g., a family member or caregiver).

The data for a level-III visit is considered limited and requires a total of two points. You can earn two points by reviewing or ordering two different types of tests (e.g., a complete blood count and a chest X-ray). You can also earn two points by summarizing old records or discussing the case with another health care provider.

Risk. The risk associated with an E/M visit is based on the chance that significant complications, morbidity or mortality occur during the current encounter/procedure or between the present encounter and the next one. The guidelines characterize these in the context of the presenting problems, diagnostic procedures and management options. The highest level of risk in any one of the three categories determines the overall risk.

The risk associated with a level-II visit is considered minimal. Examples include a presenting problem that is self-limited or minor; diagnostic procedures such as labs with venous puncture, chest X-rays, ECGs, EEGs, urinalysis, ultrasound and KOH preparation; or management options such as prescribing rest, gargles, elastic bandages and superficial dressings.

Level-III visits are considered to have a low level of risk. Patient encounters that involve two or more self-limited problems, one stable chronic illness or an acute uncomplicated illness would qualify. Diagnostic procedures with low risk include physiologic tests not under stress, non-cardiovascular imaging studies with contrast, superficial needle biopsies, labs requiring arterial puncture and skin biopsies. Low-risk management options include prescribing over-the-counter drugs, minor surgery with no identified risk factors, physical therapy, occupational therapy and IV fluids without additives.

LEVEL-II AND LEVEL-III ESTABLISHED PATIENT EXAMPLES

The examples below illustrate the slight differences between a level-II visit and a level-III visit. Each row includes two visits that involve a similar chief complaint, but the visit described in the left column warrants a 99212, while the visit in the right column warrants a 99213. Note that the 99213 visits include an expanded problem-focused exam and a review of systems (ROS).

Time-based billing

Another option for coding level-II and level-III encounters is to use time as your guide. According to CPT, a typical level-II visit lasts 10 minutes, while a typical level-III visit lasts 15 minutes. If counseling or coordination of care account for more than 50 percent of the visit, then you can select your E/M code based on the length of the visit. In general, the time spent face-to-face with the patient (and the time spent in counseling) should meet or exceed the listed typical visit times. Remember, the coders who audit your charts do so by counting required components as well as noting recorded visit times. If you decide to use time-based billing, make sure to include in your note that at least half of the face-to-face time was spent counseling or coordinating care (e.g., “total visit time was 15 minutes, half of which was counseling”). Your documentation should also describe the nature of the counseling or care coordination.

Coding with confidence

Although E/M coding is not always instinctive, understanding the differences between level-II and level-III visits will help you choose the appropriate code for your patient encounters and receive the proper reimbursement for your work. Every day you provide your patients with the best possible care. Document it accurately and code with confidence.

Continue Reading

More in fpm, more in pubmed.

Copyright © 2007 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

When to Visit the ER

Unsure when to visit the ER? Learn about common signs and symptoms that indicate you should seek emergency care.

This article is based on reporting that features expert sources.

Getty Images

It's 2 a.m., and you wake up with a terrible pain in your lower back . It's 5 p.m. on a Sunday afternoon, and you suddenly feel extremely nauseous. It's 9 a.m. on a Wednesday morning, and the cough that's been bothering you suddenly seems to take a turn for the worse. What should you do?

Depending on the severity of the problem and your overall health, the answer to that question may be to head to the emergency room – a unit within your local hospital that handles all manner of emergent medical issues.

“ER providers are able to very quickly assess and treat sudden, serious and often life-threatening health issues,” explains Dr. Sameer Amin, chief medical officer with L.A. Care Health Plan, the largest publicly operated health plan in the country that serves nearly 2.9 million members.

The ER, also known as the emergency department, is open 24/7 and can handle a wide range of illnesses, including physical and psychiatric issues, adds Patrick Cassell, patient care administration, emergency services, with Orlando Health in Florida.

Some ERs are Level 1 trauma centers that can handle “very high-level stuff,” he explains, while others, such as those in a community hospital or more rural settings, might need to transfer patients to a larger facility. These transfers happen when the acuity (severity) of the need exceeds the hospital's capacity to care for the patient on-site.

Common Reasons to Visit the ER

So, what constitutes an emergency?

“For us, an emergency is what the patient thinks is an emergency,” Cassell says. “It’s something that we don’t get judge-y about.”

According to a report from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, in 2018 (the most recent year data was available), U.S. residents made 143.5 million emergency room visits. Circulatory and digestive system conditions were the most common reasons for an emergency room visit, and 14% of those seen in the ER were admitted to the hospital .

Some common reasons to visit the ER include:

- Chest pains .

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing.

- Abdominal pain, which may be a sign of appendicitis , bowel obstruction, food poisoning or ulcers .

- Uncontrollable nausea or vomiting.

- COVID-19, influenza and other respiratory infections .

- Severe headaches .

- Weakness or numbness.

- Complications during pregnancy .

- Injuries, such as broken bones, sprains, cuts or open wounds.

- Urinary tract infections .

- Dizziness, hallucinations and fainting .

- Mental health disorders or suicide attempts.

- Substance use disorders.

- Back pain .

- Skin infections, rashes or lesions on the skin.

- Foreign object stuck inside the body.

- Tooth aches .

When to Seek Urgent Care Instead of the ER

If you're questioning where to seek care, you should opt for the emergency room if you might have a potentially serious condition or are in severe pain, advises Dr. Brian Lee, medical director of the Emergency Care Center at Providence St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, California.

However, if you’re having a medical issue that’s not a full-blown emergency, but your primary care provider can’t get you in for an appointment, that’s a good time to head to an urgent care provider.

“Urgent care clinics are best equipped for a less dire level of care,” Amin explains. “They fill the gaps when the health concern will not require a hospital stay but still needs immediate treatment.”

Deciding between the ER and urgent care also depends on your medical history, notes Dr. Christopher E. San Miguel, clinical assistant professor of emergency medicine with the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus. For example, most people with a cough and a low-grade fever can be treated at an urgent care clinic without difficulty.

“If, however, you have a history of a lung transplant, you should probably be seen for your cough and fever at an ED,” he recommends.

Because urgent care centers typically offer less robust interventions than what you’d find at the emergency room, they can’t help in all situations. They can, however, refer you to a local ER if you do require more intensive care. They also tend to have a lower deductible than the ER, “and if you’re paying out of pocket, urgent cares can be cheaper than an emergency department typically,” Cassell says.

Cost of Urgent Care vs. ER

On the cost front, San Miguel says there are a few factors to be aware of, particularly if funds are an issue.

“Urgent cares are like any other outpatient health care office – they can require payment up front and decline to see patients who are unable to pay,” San Miguel explains.

Emergency departments, however, are compelled by federal law – the Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act, which was enacted in 1986 – to see patients and assess them for “life- or limb-threatening illness and injuries regardless of their ability to pay,” he says.

While this means that the ER must see you, they can “decline to treat non-life-threatening problems once they determine that they are non-life-threatening,” San Miguel adds.

You won’t be charged a fee upfront to be seen in the emergency room, but the hospital can and will bill you after you’ve been discharged.

When you accept treatment at the emergency department, “you’re still ultimately accepting responsibility for the bill ,” San Miguel points out. “And because of the nature of providing a 24-hour service that is prepared to handle any emergency, the cost of care in the ED is much higher than the cost in an urgent care.”

If you find yourself in a situation where you’ve received emergency care but are unable to pay, you should call the billing office as soon as possible to talk about your options.

“Often the bill will be reduced and you’ll be placed on a reasonable payment plan,” San Miguel says.

For any non-urgent or ongoing health concerns, visit with your primary care provider, Amin adds.

“It’s always better to have longstanding issues taken care of in a calm and collected manner during normal business hours,” he explains.

How Long Is the Wait at an ER?

Before you arrive, consider that you could be in for a long wait, depending on the type of problem you’re having and the situation inside the ER.

“We don’t operate on a first-come, first-served basis. It’s based on how sick you are,” Cassell explains.

For instance, he says, patients with more severe illnesses, such as a suspected heart attack or stroke , will take precedence over less severe problems, such as a sprain or an earache .

Even though you may walk in and find an empty waiting room and assume you’ll be seen quickly, there could be all sorts of activity going on behind the scenes. Especially in larger ERs, ambulances may be arriving with sick patients or the ER may already be very busy with sicker patients. You will get the same triage if you come by ambulance or walk in to the ER.

So rest assured that if you are very sick, you will get brought back immediately if you walk into ER. Similarly, if you take an ambulance for broken toe, it wont get you in sooner. You will likely be placed in waiting room if ER full.

San Miguel adds, “The best thing you can do is to let the triage/registration team know if there has been a change in your symptoms while you are waiting. For instance, if your chest pain is getting worse or if you are now having trouble breathing, this should prompt the team to reassess you and make sure you are triaged appropriately.”

What Should You Do While You're Waiting to Be Seen?

While you’re waiting, Amin recommends considering what the provider will ask you, such as:

- When did symptoms start?

- How long have they been going on for? Have they changed in severity or frequency?

- Are symptoms related to a health issue you’re being treated for?

- What triggered your visit to the ER today?

You should also bring a list of your medications, health conditions and history, such as chronic conditions and previous surgeries. It's also a good idea to have the names of the providers on your care team, including your primary care doctor and any specialist. Having this information at the ready is especially helpful if you’re headed to an ER that’s outside of the health system you typically use.

“It’s immensely valuable if patients are able to provide us with an accurate history of their medical problems and current medications,” San Miguel notes. “Unfortunately, not all electronic health systems communicate with each other, and in the middle of the night, it can be impossible to request records from another hospital.”

What Happens When You See an ER Provider

When you are brought in to see a provider, the initial aim of the interaction is to assess what’s going on and make sure you’re stabilized.

For some patients, a "big point of frustration is the need to tell their symptoms to more than one person," San Miguel says. "It seems like we’re quite unorganized and not communicating with each other, but in reality, we just know that the patients themselves are the best source of information about their own symptoms.”

As the physician, San Miguel always reads the notes that come from the initial intake, “but I want to confirm the details directly with you.”

While you will receive some care on the spot, most of your treatment will take place elsewhere, Cassel adds.

“With the exception of putting in stitches to fix a cut, the emergency department is not in and of itself a definitive care spot. Definitive care takes place outside of the ED,” he says.

This means that once the care team determines what’s going on and what care you need, you’ll either be admitted to the hospital for more intensive treatment or sent home with care instructions and a plan for additional follow-up if necessary.

For example, if you are having a heart attack , you’ll be admitted to an inpatient unit in the hospital for more testing and stabilization. If you’ve come in for an earache, you’ll probably be given a prescription and sent home. You'll then use those medications and recover with instructions to follow up with your primary care provider as soon as they can see you.

Lee underscores that “emergency and urgent care is not complete care. It is an acute intervention that addresses specific issues that often require further attention in the ambulatory office setting.”

Lastly, remember that the providers you’re working with are doing their best to look after you in a timely, helpful fashion. The ER staff understand you have been waiting, but they have no control over how many patients show up at once. If a surge of patients show up in an hour, the ER doesn't have the ability to suddenly bring on more staff. This happens more frequently than people realize.

Cassell says that the people who staff the emergency department are there “because we love it. We are task-focused, and we’re often very busy going from place to place, but we really do care.”

Keep in mind that the ER is not generally a calm place and the patient experience will be different from what you might get if you’re admitted in the hospital.

What to Pack in Your Hospital Bag

The U.S. News Health team delivers accurate information about health, nutrition and fitness, as well as in-depth medical condition guides. All of our stories rely on multiple, independent sources and experts in the field, such as medical doctors and licensed nutritionists. To learn more about how we keep our content accurate and trustworthy, read our editorial guidelines .

Amin is chief medical officer of L.A. Care Health Plan, the largest publicly operated health plan in the U.S.

Cassell is patient care administrator, emergency services, with Orlando Health in Florida.

Lee is medical director of the Emergency Care Center at Providence St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, California.

San Miguel is clinical assistant professor of emergency medicine with the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus.

Tags: health , patients , patient advice , hospitals

Most Popular

Patient Advice

health disclaimer »

Disclaimer and a note about your health ».

Your Health

A guide to nutrition and wellness from the health team at U.S. News & World Report.

You May Also Like

Does medicare cover alert systems.

Paul Wynn June 14, 2024

Ways to Overcome Anger or a Bad Mood

Vanessa Caceres June 14, 2024

Esthetician vs. Dermatologist

Elaine K. Howley June 14, 2024

When to Do an Eye Exam

Claire Wolters June 13, 2024

Does Medicare Cover Botox?

Paul Wynn June 13, 2024

Can You Be Vegan During Pregnancy?

Janet Helm June 11, 2024

Should You Get a Full-Body MRI?

Claire Wolters June 11, 2024

How Are Patients Choosing ASCs?

Paul Wynn June 10, 2024

Medicare IRMAA 2024

C.J. Trent-Gurbuz June 10, 2024

Breastfeeding Tips

Vanessa Caceres June 7, 2024

- Find a Doctor

- Patients & Visitors

- ER Wait Times

- For Medical Professionals

- Piedmont MyChart

- Medical Professionals

- Find Doctors

- Find Locations

Receive helpful health tips, health news, recipes and more right to your inbox.

Sign up to receive the Living Real Change Newsletter

What to expect in the emergency department

“The emergency department is an area in the hospital where we can quickly assess patients, make them better, or decide they’re going to need additional testing or management and admit them to the hospital,” says Jeffrey Oyler, M.D. , an emergency medicine physician at Piedmont Atlanta Hospital .

Every patient who visits the emergency department (ED) will go through triage, which allows the ED team to establish the severity of that person’s condition. Triage takes into account the patient’s vital signs, as well as his or her complaint. Dr. Oyler says measuring the patient’s vital signs is the most crucial component of triage because these signs are essential to assessing the patient and are something that cannot be faked. The patient is then categorized based on the Emergency Severity Index:

- Level 1 – Immediate: life-threatening

- Level 2 – Emergency: could be life-threatening

- Level 3 – Urgent: not life-threatening

- Level 4 – Semi-urgent: not life-threatening

- Level 5 – Non-urgent: needs treatment as time permits

“It’s hugely important for us to establish who is the sickest, so we can provide the interventional care they need immediately, then work our way down the list as fast as we can,” says Dr. Oyler. Based on the assessment by the triage nurse, the patient will either be:

- Taken to an exam room. If all rooms are full, that person will be next in line for a room. Dr. Oyler emphasizes that patients are not seen in the order of arrival, but based on the severity of their condition.

- Offered a fast-track service. The fast track does not have all of the capabilities of the emergency department, but is intended to help patients with minor emergencies get through the system. People in the waiting room may see other patients with minor injuries being called back before those with more serious injuries, but they are actually being treated in the fast-track area, Dr. Oyler explains.

Behind the waiting room doors

“A quiet waiting room is something we ideally love to have, but it is not a reflection of what is going on in the back,” says Dr. Oyler. “You can have one person or 20 people in your waiting room, but you could have complete chaos in the back with very, very sick patients.” Although the ED waiting room may not seem busy, the behind-the-scenes ambulance bay can bring in patients at all hours of the day. “You can have an incredibly long wait in our emergency department if you show up with a non-life-threatening condition that could have waited for treatment at your primary care physician’s office the next day,” he says. “We are sensitive to the fact that you are waiting,” says Dr. Oyler. “We want you to get back to a room and be seen as fast as possible, but we’re also prioritizing care for people who absolutely have to have it right then and there.” Dr. Oyler stresses the importance of patience if your illness or injury is not life-threatening. “We know you’re suffering and it’s not what we desire, but when your time comes, you’re going to get the service you wanted.” If your condition is not an emergency, you can save time and money by visiting an urgent care center or your primary care physician’s office. Insurance co-pays are usually more expensive at the emergency department compared to co-pays at other facilities. For more information on emergency services throughout the Piedmont system, visit our locations map to choose an emergency room near you .

Need to make an appointment with a Piedmont physician? Save time, book online .

- emergency department

- Emergency Medicine

- Jeffrey Oyler

- urgent care

Related Stories

Schedule your appointment online

Schedule with our online booking tool

*We have detected that you are using an unsupported or outdated browser. An update is not required, but for best search experience we strongly recommend updating to the latest version of Chrome, Firefox, Safari, or Internet Explorer 11+

Share this story

Download the Piedmont Now app

- Indoor Hospital Navigation

- Find & Save Physicians

- Online Scheduling

Download the app today!

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Hospital Emergency Room Visits per 1,000 Population by Ownership Type

Data are loading.

- Hospital Utilization

'Really astonishing': Average cost of hospital ER visit surges 176% in a decade, report says

Hospital emergency rooms are more likely to charge pricier levels of care than a decade ago, generating bigger bills that consumers increasingly must pay with their own money, according to a new report.

The nonprofit Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI) examined insurance claims for a decade’s worth of hospital emergency room bills , analyzing millions of insurance claims for people under the age of 65 who get health insurance through an employer.

HCCI found that hospital emergency rooms not only substantially increased prices for care from 2008 through 2017. The hospitals and doctors also billed for more complex care, which allows them to collect more lucrative fees from consumers, employers and private insurers.

The average emergency room visit cost $1,389 in 2017, up 176% over the decade. That is the cost of entry for emergency care; it does not include extra charges such as blood tests, IVs, drugs or other treatments.

“When you look at the last 10 years, it’s really astonishing how this average cost of admission to the ER has gone up,” says HCCI senior researcher John Hargraves, who presented his report this week at the AcademyHealth meeting in Washington, D.C.

Last month, President Trump called on Congress to curb surprise medical billing , which describes when a consumer gets an often-expensive bill from a hospital or doctor that is not part of their insurance network. Many states already have passed legislation to address these unexpected bills .

More: Trump has the power to save seniors' lives and fix a surprise billing issue in Medicare

It comes down to the codes

But less attention has been paid on how ERs bill patients.

Every hospital emergency room visit is assessed on a scale of 1 to 5 – a figure intended to gauge medical complexity and the amount a consumer will be billed.

An insect bite might be assigned the lowest billing code, 99281. A heart attack, the highest code, 99285.

The difference in how an emergency room visit is coded might cost a consumer hundreds more for simply stepping in the building.

In 2008, 17% of hospital visits were charged the most expensive code. That surged to 27% of visits in 2017, the report said. The average price for the most expensive code more than doubled from $754 in 2008 to $1,895 in 2017.

Hospitals also increased billings for the second most expensive code, but they billed the three least expensive codes less often compared to a decade ago.

Are we sicker? Or just being billed like it?

Does that mean Americans became sicker over the past decade, requiring more intense and complex care at hospital emergency rooms? The report does not address that question.

Americans don't go to the hospital ER more often than they did a decade ago, the report said. However, those visits cost more and are more likely billed with more expensive codes.

"We don't see a big rise in overall ER rates," Hargraves says. "Which is what you'd expect if there's a large increase of people having heart attacks or other (more severe) things. I think that's telling."

The report combines the amount charged by hospitals and doctors, who often bill patients separately.

Hospital industry officials point to their own studies to explain the increased use of more expensive codes at emergency rooms.

An American Hospital Association report found the average number of emergency room visits per 1,000 patients increased nearly 12% between 2006 and 2010. The report also found those adults had a rising level of illness. The report examined hospital use by older adults eligible for Medicare; HCCI reported on hospital claims of people under the age of 65.

“Hospital emergency departments treat many of our nation’s sickest and most complex patients,” says Ashley Thompson, senior vice president of policy at the American Hospital Association. “As hospitals serve as the front-door for dealing with issues ranging from violence, mental health conditions and the opioid epidemic , the number and complexity of ED visits overall continues to increase.”

The decade-long change in billing practices comes as hospitals have shifted to electronic health records systems. These computerized systems might prompt hospital staff to better document care, which might support the use of more expensive codes, Hargraves said.

Others aren't so sure.

Whistleblowers

Jeffrey Newman is a Boston attorney who has represented whistleblowers under the federal False Claims Act. The federal law allows individuals to bring lawsuits on behalf of the government and collect a portion of any settlement. The law is often used by ex-employees of hospitals, medical practices, drug companies or medical-device makers when they suspect a former employer is improperly billing federal health programs such as Medicare or Medicaid.

In March, a nurse practitioner represented by Newman settled a False Claims Act case for $2.1 million against CareWell Urgent Care Centers.

The settlement said that CareWell managers directed doctors and other medical providers ask patients about 13 body parts or systems and examine at least 9 areas, even if the patient's symptoms that did not require such extra attention.

If the doctors did not ask the questions, the urgent care center's medical records system registered a "no" answer. The robust queries were meant to ensure the urgent care center could bill at a higher level reimbursement code, the settlement said.

Newman said he believes there are not enough checks and balances to guarantee medical services are properly coded.

"They can find reasons to say they were doing more complex things," Newman says. "They often see this as an easy mark to pump the services and say, 'We're being better doctors,' when it contravenes the rules."

You may also be interested in:

- Making medical bills transparent

- Millions in medical debt gone, thanks to these churches

- Doctors, hospitals sue patients who post negative comments, reviews on social media

- Free In-Person Regional Events Focused on Oncology and Population Health

- Conferences

Publication

A Revised Classification Algorithm for Assessing Emergency Department Visit Severity of Populations

An updated emergency visit classification tool enables managers to make valid inferences about levels of appropriateness of emergency department utilization and healthcare needs within a population.

ABSTRACT Objectives: Analyses of emergency department (ED) use require visit classification algorithms based on administrative data. Our objectives were to present an expanded and revised version of an existing algorithm and to use this tool to characterize patterns of ED use across US hospitals and within a large sample of health plan enrollees.

Study Design: Observational study using National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey ED public use files and hospital billing data for a health plan cohort.

Methods: Our Johns Hopkins University (JHU) team classified many uncategorized diagnosis codes into existing New York University Emergency Department Algorithm (NYU-EDA) categories and added 3 severity levels to the injury category. We termed this new algorithm the NYU/JHU-EDA. We then compared visit distributions across these 2 algorithms and 2 other previous revised versions of the NYU-EDA using our 2 data sources.

Results: Applying the newly developed NYU/JHU-EDA, we classified 99% of visits. Based on our analyses, it is evident that an even greater number of US ED visits than categorized by the NYU-EDA are nonemergent. For the first time, we provide a more complete picture of the level of severity among patients treated for injuries within US hospital EDs, with about 86% of such visits being nonsevere. Also, both the original and updated classification tools suggest that, of the 38% of ED visits that are clinically emergent, the majority either do not require ED resources or could have been avoided with better primary care.

Conclusions: The updated NYU/JHU-EDA taxonomy appears to offer cogent retrospective inferences about population-level ED utilization.

Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(3):119-125. https://doi.org/10.37765/ajmc.2020.42636

Takeaway Points

- There is renewed interest in understanding emergency department (ED) use patterns in populations, both because of increased use associated with healthcare reform and as private payers seek to stem their rising ED spending.

- To assess the appropriateness of ED use at the population level, validated classification methods that use available administrative data will be required.

- Our analysis using an updated classification suggests that an even greater number of ED visits than previously categorized are nonemergent.

- Health plans and other organizations might use ED visit classification algorithms to gain an understanding about how populations make use of hospital services.

The New York University Emergency Department Algorithm (NYU-EDA) is widely used to classify emergency department (ED) visits. 1,2 This measurement tool’s development occurred in the late 1990s and was based on 5700 ED discharge abstracts from 6 hospitals in the Bronx, a borough of New York City. The NYU-EDA probabilistically classified 659 diagnosis codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification ( ICD-9-CM ). The original NYU-EDA mapped only about 5% of all ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes. We propose an algorithm that remedies this shortfall and classifies nearly all ED visits.

The NYU-EDA has been applied in health services research studies to identify emergent visits that required ED care. 3,4 Several studies have focused on nonemergent and primary care—treatable ED visits and evaluated emergent and nonemergent utilization patterns to assess the impact of healthcare reforms. 5-11 Estimates of proportions of nonemergent visits have ranged between 17% and 49%. One study looked at primary care—sensitive (PCS) visits (ie, emergent visits that are potentially avoidable and nonemergent and primary care–treatable visits) and found that up to 50% of ED visits were PCS in a statewide all-payer claims database with 92% of ED visits classified. 12

Evidence for the validity of the NYU-EDA has grown over 2 decades. Emergent visits were associated with total charges and increased likelihood of death and inpatient hospitalization directly from the ED and within 30 days from a previous visit. 10,13-15 However, researchers and emergency medicine clinicians have cautioned against using visit classifications based solely on discharge diagnoses for interventions aimed at reducing unnecessary visits or for denying payment. First, underlying differences in morbidity and access to care may, to some degree, account for utilization patterns that would be detected by an ED visit classification algorithm. Second, there are reasons for visits on the individual level that may be appropriate for ED utilization, which can differ from discharge diagnoses that categorize the encounter as nonemergent. For example, patients who are experiencing chest pain and come to the ED for evaluation are not necessarily inappropriately using the ED. ED visit classifications are useful tools for understanding the healthcare needs of populations, not the medical needs of individual patients. 16-19

A team of Johns Hopkins University (JHU) emergency medicine physicians and health services researchers has further updated and expanded the NYU-EDA using their best clinical judgment and diagnosis aggregations from the Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) System. 20 In this revised JHU version of the NYU-EDA (or NYU/JHU-EDA for short) we undertook 3 significant modifications and improvements to the original version and updates undertaken by other teams. First, rather than assigning ICD codes probabilistically, we classify each ED visit into 1 of 11 categories. Second, rather than placing all injuries into 1 category, we subcategorize injuries into 3 severity levels: nonsevere injuries, severe injuries, and severe injuries that are likely to require inpatient admissions. Third, we significantly expand the classification of ICD codes.

In this article, we describe the updated NYU/JHU-EDA, and, using data from a federal survey of US hospital EDs and a large claims database from multiple health plans, we compare results of our revised tool with the original NYU-EDA and 2 earlier modifications developed by Johnston et al and Ballard et al. 2,13

The first objective of this article is to offer a description and first-stage assessment of our ED classification algorithm. The second goal is to use this methodology to offer an account of use patterns of American EDs based on a representative sample of patients visiting hospital EDs and a large national sample of health plan enrollees. In addition to describing our new measurement tool, our analysis adds to the literature on how Americans use EDs and will offer insights into how health plans and other organizations might use classification algorithms to gain an understanding of how populations make use of hospital EDs.

Review of Previous Approaches for Classifying ED Visits

The original NYU-EDA first classifies common primary ED discharge diagnoses as having varying probabilities of falling into each of the 4 following categories: (1) nonemergent; (2) emergent, primary care treatable; (3) emergent, ED care needed, and preventable or avoidable with timely and effective ambulatory care; and (4) emergent, ED care needed, and not preventable. 1 The original NYU system categorizes certain diagnoses separately and directly into 5 additional categories: injuries, psychiatric conditions, alcohol related, drug related, or unclassified.

The adaptation by Ballard et al sums the NYU-EDA probabilities for nonemergent and emergent primary care—treatable visits and compares this sum with the total probability of the emergent, ED care needed categories. 13 Depending on the larger of the 2 resultant likelihoods, visits are classified as nonemergent or emergent, or as intermediate when there is an equal probability of being nonemergent or emergent. The Ballard et al method classifies visits into 1 of 8 categories, which have been shown to be a good predictor of subsequent hospitalization and death within 30 days of an ED visit. 13

After 2001, the NYU-EDA was not updated, and newly added diagnosis codes were not classified. In 2018, Johnston and colleagues identified new codes that are “nested” within previously classified diagnoses and applied the original probabilistic weights to these codes. 2 New diagnoses that remained unclassified were “bridged” to already weighted codes using ICD -based condition groupings from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification System. 21 Instances in which a new diagnosis mapped to several codes with different weights were resolved in favor of a code most likely to represent an unavoidable emergent visit. 2 Because assigned weights sum to 1, both the original NYU-EDA and the update by Johnston et al describe a collection of ED visits by averaging weights.

We took a different approach to update, enhance, and expand the NYU-EDA method. We did not use probabilities but rather assigned primary discharge diagnoses to single classes and uniquely classified each ED visit. For codes that had been previously included in the original NYU-EDA, we based our updated assignments on the category with the highest probability. We resolved cases of equally high probabilities among multiple categories by giving preference to the emergent, ED care needed category.

Data Sources

To build our revised methodology, we combined ED encounter data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) from the period of 2009 to 2013. We used data from the 2014 survey for validation. 22 The reason for an ED visit is present in NHAMCS data and contained mainly signs and symptom diagnoses, but it was not present in claims. We used discharge diagnoses only and thus retained a key characteristic of the NYU-EDA and previous revised versions. Second, we extracted hospital ED claims from a large health insurance plan database. We obtained health plan claims data from QuintilesIMS (Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania [on November 6, 2017, the name of the organization changed to IQVIA]). The claims extract spanned the same time period (2009-2013) and included 14 commercial health plans; 6 of these plans also had Medicaid and Medicare managed care enrollees. The database consisted of patient enrollment data, ICD-9-CM diagnoses, hospital revenue center codes, procedures coded with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), and plan-allowed amounts for medical services.

Following the literature, we identified ED visits in the claims database through the presence of revenue center codes (0450-0459, 0981) and CPT codes for evaluation and management (EM) services in the ED (99281-99285). 23,24 We resolved instances in which facility and professional claims indicated different primary diagnoses by prioritizing facility bills. Our rationale for giving diagnoses on facility bills priority over professional bills for the same visit is that facility bills relate more closely to the final discharge record, whereas some professional claims may contain preliminary diagnoses.

Development of the NYU/JHU EDA

We applied the Johns Hopkins ACG system to help categorize diagnoses that were not included in the original NYU-EDA method. The system assigns diagnoses found in claims or encounter data to 1 of 32 Aggregated Diagnosis Groups (ADGs) (ie, morbidity types with similar expected need for healthcare resources). 25,26 The ACG system also maps diagnoses to 1 of 282 Expanded Diagnosis Clusters (EDCs) (ie, clinically homogeneous groups of diagnoses).

To help expand the scope of the NYU-EDA visit classification to more diagnoses, we formed “clinical classification cells” for ICD codes falling within combinations of ADGs and EDC clusters. Each unique cell was reviewed and categorized by our clinician team of 3 practicing emergency physicians (K.P., D.M.R, and Dr Alan Hsu).

For classification cells with ICD codes that were not previously classified with NYU-assigned probabilities, 2 of our clinicians independently assigned an ED visit class. After differences among approximately 35% of all manual assignments were reconciled and finalized by the third clinician, we developed majority class assignments for the remaining diagnoses within classification cells. Relatively uncommon diagnoses within cells that contained only codes without any original NYU-EDA weights or any manually assigned diagnosis remained unclassified. Using this approach, our NYU/JHU-EDA currently classifies 10,723 ICD-9-CM and 74,329 International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification ( ICD-10-CM ) codes ( eAppendix Tables 1 and 2 [ eAppendix available at ajmc.com ] provide examples of common ICD codes in each NYU/JHU-EDA category).

To help us assign severity levels to ACG-based classification cells consisting of injury-related diagnoses, we used CPT codes for EM services associated with ED visits and further assessed whether visits resulted in an inpatient admission. EM codes classify severity from minor (99281) to high with immediate threat to life or physiologic function (99285). We counted the number of nonsevere injury visits (99281-99283) and the number of severe injury visits (99284, 99285) in our health insurance claims data sets. Based on the larger of the 2 counts, each of our injury diagnosis clusters was classified as being either nonsevere or severe. A subset of severe injury visits was identified as likely to require inpatient hospitalization based on a greater than 50% likelihood of cases being admitted. All injury ICD clusters that were so assigned into 1 of 3 severity levels underwent a final clinical review by our clinician team. A graphic overview of the final classification categories of our revised NYU/JHU-EDA grouping taxonomy is presented in the Figure .

Statistical Analysis

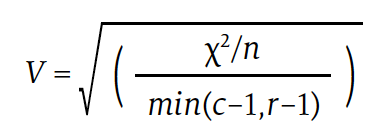

We conducted pairwise comparisons of visit distributions among the 4 EDA versions applied to NHAMCS and health plan data and computed Cramér’s V measure of association. Cramér’s V is a number between 0 and 1 that indicates how strongly 2 categorical variables are associated. It is based on Pearson’s χ 2 statistic and computed as follows:

Download PDF: A Revised Classification Algorithm for Assessing Emergency Department Visit Severity of Populations

Adolescent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Decade of Rising Surgical Cost

Health Equity Conversations: Managing Underserved Communities and Value-Based Payment

Experts Highlight How GLP-1s Have Revolutionized Management of T2D and Obesity

Health Equity Conversations: Barriers to Equitable Care

How the IRA Has Unraveled the “Biotech Social Contract”

Hospital Strategies in Commercial Episode-Based Reimbursement

2 Commerce Drive Suite 100 Cranbury, NJ 08512

© 2024 MJH Life Sciences ® and AJMC® . All rights reserved.

- Ver contenido en español . página externa

- Help in other languages . external page

- View by A-Z

- View by Location

- View by Category

Emergency Medicine

Address Hospital Bldg – Dept 100, 1st Floor 700 Lawrence Expy Santa Clara, CA 95051

Contact us Information: 408-851-5300

Hours 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

If you have an emergency medical condition, call 911 or go to the nearest hospital.

When you are experiencing a life- or limb-threatening emergency, then a visit to the emergency room is necessary.

An emergency medical condition is a medical or psychiatric condition that manifests itself by acute symptoms of sufficient severity (including severe pain) such that you could reasonably expect the absence of immediate medical attention to result in serious jeopardy to your health, serious impairment to your bodily functions, or serious dysfunction of any bodily organ or part. An Emergency Medical Condition is also “active labor,” which means a labor when there is inadequate time for safe transfer to a Plan Hospital (or designated hospital) before delivery or if a transfer poses a threat to the health of the member or unborn child.

OUR DOCTORS

- Emergency Medicine Doctors

- Dealing with Emergencies

- Choking Rescue Procedure (Heimlich Maneuver)

- Choking Rescue for Babies

- Shop Our Plans

- Easier Health Care . external page

- Specialty Care . external page

- Maternity . external page

- Total Health For All . external page

- Price Transparency . external page

Our Regions

- Northern California

- Southern California

- Mid-Atlantic States

- Oregon/SW Washington

Visit Our Other Sites

- KP.org . external page

- Individual & Family Plans . external page

- For Businesses

- Medical Financial Assistance . external page

- For Federal Employees

- Health Care Reform

- Accessibility . external page

- Terms & Conditions

- Technical Information

- Privacy Statement

- Nondiscrimination Policy

Most features are available only to members receiving care at Kaiser Permanente medical facilities.

Kaiser Permanente health plans around the country: Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc., in Northern and Southern California and Hawaii • Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Colorado • Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Georgia, Inc., Nine Piedmont Center, 3495 Piedmont Road NE, Atlanta, GA 30305, 404-364-7000 • Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of the Mid-Atlantic States, Inc., in Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, D.C., 2101 E. Jefferson St., Rockville, MD 20852 • Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of the Northwest, 500 NE Multnomah St., Suite 100, Portland, OR 97232 • Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Washington or Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Washington Options, Inc., 1300 SW 27th St., Renton, WA 98057

- Doctors, Clinics & Locations, Conditions & Treatments

- Patients & Visitors

- Medical Records

- Support Groups

- Help Paying Your Bill

- COVID-19 Resource Center

- Locations and Parking

- Visitor Policy

- Hospital Check-in

- Video Visits

- International Patients

View the changes to our visitor policy

View information for Guest Services

New to MyHealth?

Manage Your Care From Anywhere.

Access your health information from any device with MyHealth. You can message your clinic, view lab results, schedule an appointment, and pay your bill.

ALREADY HAVE AN ACCESS CODE?

Don't have an access code, need more details.

Learn More about MyHealth Learn More about Video Visits

MyHealth for Mobile

Get the iPhone MyHealth app Get the Android MyHealth app

WELCOME BACK

Emergency department.

We continue serving our community’s adults and children. As one of the most advanced trauma centers in the world, we are uniquely equipped to handle all cases at all times, even in unprecedented circumstances. Our systems have allowed us to adapt while maintaining the highest standards for safety.

We are ready for your emergency »

Leaders in Emergency Medicine

Stanford Health Care provides world-class emergency care, with adult and pediatric emergency departments in Palo Alto and an emergency department in Pleasanton serving all patients.

The Marc and Laura Andreessen Adult Emergency Department in Palo Alto is the only Level 1 Trauma Center between San Francisco and the South Bay. It serves the San Mateo and Santa Clara County communities and is a transfer center for facilities across and beyond the state of California that need the specialized expertise that Stanford Medicine offers. The Emergency Department is dedicated to rapid interventions and has designations as a Comprehensive Stroke Center and Chest Pain Center.

The Marc and Laura Andreessen Pediatric Emergency Department in Palo Alto is the only Level 1 Pediatric Trauma Center between San Francisco and the South Bay. It provides an environment that is non-threatening and calming for children as well as informative and assuring to parents. It is equipped to treat anything from colds and upset stomach to chronic or critical illnesses. It is located just down the hall from Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford.

The Stanford Health Care Tri-Valley Emergency Department in Pleasanton is equipped to manage injuries and illnesses that range from minor to life threatening. It serves the Tri-Valley community, providing integral care to the region. The Emergency Department has designation as a Primary Stroke Center. The hospital maintains the highest quality and safety ratings and is a recognized leader in maternity care. Learn about safety during the pandemic »

Marc and Laura Andreessen Adult Emergency Department

1199 Welch Road Palo Alto, CA 94304 Phone: 650-723-5111

Marc and Laura Andreessen Pediatric Emergency Department

900 Quarry Road Extension Palo Alto, CA 94304 Phone: 650-723-5111

Stanford Health Care - Tri-Valley Emergency Department

5555 W. Las Positas Blvd Pleasanton, CA 94588 Phone: 925-416-3418

Our Doctors

Our advanced practice providers.

The doctors listed here serve the Marc and Laura Andreessen Adult and Pediatric Emergency Departments in Palo Alto. This list is not a comprehensive list of all Stanford Health Care emergency providers.

Stanford Transfer Center

The Transfer Center serves as a gateway for requests from other facilities. Staffed by communications specialists and registered nurses, the Transfer Center triages requests made by physicians wishing to transfer a patient to Stanford Hospital and Stanford Health Care – ValleyCare.

The goals of the Transfer Center are:

- To provide a single point of contact for physicians wishing to access hospital services.

- To ensure appropriate utilization of resources.

- To use a multidisciplinary approach coordinating with physicians, Transfer Center staff, case managers, and financial counselors.

- To explore the benefits of bringing a patient to Stanford from an outlying facility.

- To expedite patient transfers.

- To limit potential financial liability on the part of patients and their families.

The Transfer Center is open seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day to take calls related to patient transfers.

Phone: 1-800-800-1551

Fax: 650-723-6505

24 hours - 7 days a week

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Respiratory Virus Data Channel Weekly Snapshot

Provides a summary of the key viral respiratory illness findings for COVID-19, influenza, and RSV from the past week and access to additional information and figures.

Note: data summaries are based on CDC subject matter expert interpretation of publicly available findings across multiple data systems, some of which are not included in the data visualizations on these web pages.

The amount of respiratory illness (fever plus cough or sore throat) causing people to seek healthcare continues to decrease across most areas of the country. This week, no jurisdictions experienced moderate, high, or very high activity compared to 1 jurisdiction experiencing moderate activity (0 high or very high) the previous week.

Reported on Friday, May 3rd, 2024.

Seasonal influenza, COVID-19, and RSV activity continues to decrease in most areas of the country. Hospital bed occupancy for all patients, including within ICUs, remains stable nationally.

Most key indicators, including wastewater viral activity , are showing low levels of activity nationally.

Nationally, seasonal influenza activity continues to decrease. Additional information about current influenza activity can be found at: Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report | CDC

All ten regions of the country are below the 3% percent positivity epidemic threshold indicating that the RSV season has ended. Hospitalization rates are low in all age groups.

Vaccination

National vaccination coverage for COVID-19, influenza, and RSV vaccines remained low for children and adults for the 2023-24 respiratory illness season. COVID-19 vaccines continue to be recommended and can provide a layer of protection.

Discover data stories

Provides an update on how COVID-19, influenza, and RSV may be spreading nationally and in your state.

Provides an update on how respiratory viruses are contributing to serious health outcomes, like hospitalizations and deaths, both nationally and in your state.

Provides an update on how COVID-19, influenza, and RSV illness, hospitalizations, and deaths are affecting different groups.

Provides an update on receipt of vaccination and intent for vaccination for COVID-19 (children and adults), influenza (children and adults), and RSV (adults) based on weekly updated National Immunization Survey (NIS) survey responses.

Explore deeper data

Wastewater (sewage) data specific to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, are displayed at the national, regional, and state levels. These data can provide an early signal of changes in infection levels.

Data on COVID-19 cases and deaths among residents and staff of nursing homes are displayed at the national and state levels.

Weekly trends in COVID-19-related and overall hospital bed occupancy.

Estimated trends for COVID-19 and influenza infections and hospitalizations, based on modeling and forecasting, are displayed at the national and state levels.

Descargo de responsabilidad: Es posible que en este sitio encuentre algunos enlaces que le lleven a contenido disponible sólo en inglés. Además, el contenido que se ha traducido del inglés se actualiza a menudo , lo cual puede causar la aparición temporal de algunas partes en ese idioma hasta que se termine de traducir (generalmente en 24 horas). Llame al 1-800-CDC-INFO si tiene preguntas sobre la influenza estacional, COVID-19 o el VRS cuyas respuestas no ha encontrado en este sitio. Agradecemos su paciencia.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- ACS Foundation

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- ACS Archives

- Careers at ACS

- Federal Legislation

- State Legislation

- Regulatory Issues

- Get Involved

- SurgeonsPAC

- About ACS Quality Programs

- Accreditation & Verification Programs

- Data & Registries

- Standards & Staging

- Membership & Community

- Practice Management

- Professional Growth

- News & Publications

- Information for Patients and Family

- Preparing for Your Surgery

- Recovering from Your Surgery

- Jobs for Surgeons

- Become a Member

- Media Center

Our top priority is providing value to members. Your Member Services team is here to ensure you maximize your ACS member benefits, participate in College activities, and engage with your ACS colleagues. It's all here.

- Membership Benefits

- Find a Surgeon

- Find a Hospital or Facility

- Quality Programs

- Education Programs

- Member Benefits

New Pediatric Surgical Guidance

In the latest issue of the Bulletin, we look at a new two-tier model that provides guidance to improve pediatric heart surgical care related to structure, processes, and outcome metrics.

Explore the ACS

Quality in Action

ACS-verified programs are committed to the highest standards of patient care, providing surgical teams with the tools to save and improve lives.

Call for Abstracts

Submit your abstracts for the TQIP Annual Conference by June 30. Share what internal PI efforts you have embarked on and how you use TQIP.

Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program

MBSAQIP accredits inpatient and outpatient bariatric surgery centers in the U.S. and Canada.

Latest News

Can private practice survive.

Otolaryngologist Bobby Mukkamala, MD, FACS, Becomes AMA President-Elect; Other Fellows Elected to Leadership

Learn more about several ACS Fellows recently elected to leadership in the American Medical Association.

US Surgeons: Participate in ACS Surgeon Well-Being Survey

Data from the survey will drive advocacy for workplace well-being, create national minimum standards, and more.

The House of Surgery

Hear a discussion about how surgeons in all career stages can enhance their leadership skills and use those skills to advocate for the profession.

Journal of the American College of Surgeons

Read the latest issue today!

Events & Courses

Clinical Congress 2024

Register for Clinical Congress 2024—the premier surgical education event—Saturday, October 19 through Tuesday, October 22.

Quality and Safety Conference

Register today for the 2024 ACS Quality and Safety Conference, July 18–21, to join with leaders in surgical quality improvement.

Become a member today

Associate Fellows

We're dedicated to the betterment of our members and patients everywhere. Access an extensive library of educational resources and build stronger ties with surgeons locally and around the world.

Anaphylaxis

On this page, when to see a doctor, risk factors, complications.

Anaphylaxis is a severe, life-threatening allergic reaction. It can happen seconds or minutes after you’ve been exposed to something you’re allergic to. Peanuts or bee stings are examples. In anaphylaxis, the immune system releases a flood of chemicals that can cause the body to go into shock. Blood pressure drops suddenly, and the airways narrow, blocking your breathing. The pulse may be fast and weak, and you may have a skin rash. You may also get nauseous and vomit. Anaphylaxis needs to be treated right away with an injection of epinephrine. If it isn’t treated right away, it can be deadly.

Anaphylaxis is a severe, potentially life-threatening allergic reaction. It can occur within seconds or minutes of exposure to something you're allergic to, such as peanuts or bee stings.

Anaphylaxis causes the immune system to release a flood of chemicals that can cause you to go into shock — blood pressure drops suddenly and the airways narrow, blocking breathing. Signs and symptoms include a rapid, weak pulse; a skin rash; and nausea and vomiting. Common triggers include certain foods, some medications, insect venom and latex.

Anaphylaxis requires an injection of epinephrine and a follow-up trip to an emergency room. If you don't have epinephrine, you need to go to an emergency room immediately. If anaphylaxis isn't treated right away, it can be fatal.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Symptoms of anaphylaxis include hives and itchy, pale, or flushed skin. Blood pressure may be low, it may be hard to breathe, and the pulse may be weak and fast. You may get nauseous, vomit, have diarrhea, feel dizzy, and faint. Symptoms usually happen minutes after you’ve been exposed to something you’re allergic to, but they might not appear for a half hour or longer.

Anaphylaxis symptoms usually occur within minutes of exposure to an allergen. Sometimes, however, anaphylaxis can occur a half-hour or longer after exposure. In rare cases, anaphylaxis may be delayed for hours. Signs and symptoms include:

- Skin reactions, including hives and itching and flushed or pale skin

- Low blood pressure (hypotension)

- Constriction of the airways and a swollen tongue or throat, which can cause wheezing and trouble breathing

- A weak and rapid pulse

- Nausea, vomiting or diarrhea

- Dizziness or fainting

Seek emergency medical help if you, your child or someone else you're with has a severe allergic reaction. Don't wait to see if the symptoms go away.

If you have an attack and you carry an epinephrine autoinjector, administer it right away. Even if symptoms improve after the injection, you still need to go to an emergency room to make sure symptoms don't recur, even without more exposure to the allergen. This second reaction is called biphasic anaphylaxis.

Make an appointment to see your provider if you or your child has had a severe allergy attack or signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis in the past.

The diagnosis and long-term management of anaphylaxis are complicated, so you'll probably need to see a doctor who specializes in allergies and immunology.

Anaphylaxis is caused by a severe allergic reaction. It happens when the immune system mistakes a food or substance for something that’s harmful. In response, the immune system releases a flood of chemicals to fight against it. These chemicals are what cause the symptoms of an allergic reaction. Allergy symptoms usually aren’t life-threatening, but a severe reaction can lead to anaphylaxis. The most common triggers of anaphylaxis in children are food allergies like to peanuts, milk, fish, and shellfish. In adults, stings from insects, latex, and some medications can cause anaphylaxis.

The immune system produces antibodies that defend against foreign substances. This is good when a foreign substance is harmful, such as certain bacteria or viruses. But some people's immune systems overreact to substances that don't normally cause an allergic reaction.

Allergy symptoms aren't usually life-threatening, but a severe allergic reaction can lead to anaphylaxis. Even if you or your child has had only a mild anaphylactic reaction in the past, there's a risk of more severe anaphylaxis after another exposure to the allergy-causing substance.

The most common anaphylaxis triggers in children are food allergies, such as to peanuts and tree nuts, fish, shellfish, wheat, soy, sesame and milk. Besides allergy to peanuts, nuts, fish, sesame and shellfish, anaphylaxis triggers in adults include:

- Certain medications, including antibiotics, aspirin and other pain relievers available without a prescription, and the intravenous (IV) contrast used in some imaging tests

- Stings from bees, yellow jackets, wasps, hornets and fire ants

Although not common, some people develop anaphylaxis from aerobic exercise, such as jogging, or even less intense physical activity, such as walking. Eating certain foods before exercise or exercising when the weather is hot, cold or humid also have been linked to anaphylaxis in some people. Talk with your health care provider about precautions to take when exercising.

If you don't know what triggers an allergy attack, certain tests can help identify the allergen. In some cases, the cause of anaphylaxis is not identified (idiopathic anaphylaxis).

You may be more at risk of anaphylaxis if you’ve had this reaction before or if you have allergies or asthma. Conditions like heart disease or a buildup of white blood cells can also increase your risk.

There aren't many known risk factors for anaphylaxis, but some things that might increase the risk include:

- Previous anaphylaxis. If you've had anaphylaxis once, your risk of having this serious reaction increases. Future reactions might be more severe than the first reaction.

- Allergies or asthma. People who have either condition are at increased risk of having anaphylaxis.

- Certain other conditions. These include heart disease and an irregular accumulation of a certain type of white blood cell (mastocytosis).

An anaphylactic reaction can be life-threatening — it can stop your breathing or your heartbeat.

The best way to prevent anaphylaxis is to stay away from substances that cause this severe reaction. Also:

- Wear a medical alert necklace or bracelet to indicate you have an allergy to specific drugs or other substances.