7 Great Victoria Desert Facts: A Land of Resilience and Wonder

The Great Victoria Desert, a vast expanse of arid land stretching across two Australian states, has long been a source of fascination for adventurers, scientists, and travelers. Despite its harsh conditions, this remarkable landscape boasts an impressive array of flora and fauna, as well as a rich cultural history that dates back thousands of years.

In this blog post, we delve into the key facts about the Great Victoria Desert, exploring its geography, ecology, and human history.

1. Location and Size

The Great Victoria Desert, a vast and remote expanse of arid land, is located in Australia and spans two states: South Australia and Western Australia. Its size, covering an area of approximately 422,466 square kilometers (163115.035 square miles), makes it the largest desert in Australia and the eighth largest in the world.

The Great Victoria Desert’s vast size and remoteness contribute to its low population density, with only a small number of indigenous communities and mining settlements scattered throughout the region. The desert remains largely undeveloped and unexplored, offering a unique opportunity for scientists and adventurers alike to study and experience an ancient and pristine landscape.

2. Climate and Weather

The climate of the Great Victoria Desert is characterized by its arid conditions, which are marked by low rainfall and high temperatures. These extreme conditions have shaped the landscape and the unique ecosystems in the desert.

Rainfall in the Great Victoria Desert is both scarce and unpredictable, with average annual precipitation ranging from 200 to 250 millimeters (8 to 10 inches).

The desert experiences extreme temperature fluctuations throughout the year, with summer temperatures frequently soaring up to 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit). These high temperatures, intense sunlight, and arid conditions can lead to rapid evaporation rates and extremely dry air.

3. Flora and Fauna

Despite the harsh conditions and extreme climate, the Great Victoria Desert is home to various unique plant and animal species. These organisms have evolved to survive and thrive in an environment of scarce water resources, high temperatures, and nutrient-poor soils.

The vegetation of the Great Victoria Desert is dominated by three primary types of plants: spinifex grass, acacia shrubs, and eucalyptus trees. Spinifex grass, a resilient species with deep roots that help it to access water from the soil, covers much of the desert’s sandy dunes. This grass forms dense hummocks that provide essential habitat and shelter for various small animals and reptiles.

Acacia shrubs, also known as wattles, are another common plant species found in the desert. These hardy shrubs are well-adapted to arid conditions, with small, water-conserving leaves and the ability to fix nitrogen from the atmosphere to improve soil fertility.

Many species of eucalyptus trees can also be found in the Great Victoria Desert, particularly along watercourses and in areas where groundwater is accessible. These trees provide essential habitat and food resources for various native bird and animal species.

The Great Victoria Desert is home to diverse animal species, many of which are uniquely adapted to life in this harsh environment.

The desert has a variety of lizard species, such as the at-risk great desert skink, the Central Ranges taipan, and several petite marsupials, like the imperiled sandhill dunnart and the crest-tailed mulgara.

One adaptation for survival in this terrain involves digging into the sands, a strategy employed by creatures like the southern marsupial mole and the water-holding frog.

The desert’s predators consist of the dingo (found north of the Dingo Fence) and two sizeable monitor lizards, namely the perentie and the sand goanna.

The avian population comprises species like the chestnut-breasted whiteface, which resides on the desert’s eastern border, and the malleefowl that inhabits the Mamungari Conservation Park.

4. Indigenous People and Culture

The Great Victoria Desert is the traditional home of several indigenous groups, including the Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara, and Ngaanyatjarra peoples. These indigenous communities have lived in the region for thousands of years, maintaining a strong connection to the land and its resources.

These Aboriginal groups have developed a deep knowledge of the desert’s flora, fauna, and natural processes, allowing them to survive and thrive in the challenging environment. Their traditional practices, such as hunting, gathering, and the use of fire for land management, have shaped the landscape and continue to play an important role in the desert ecosystem.

The indigenous people of the Great Victoria Desert have a rich cultural heritage intimately tied to the land. Their stories, ceremonies, and art forms often reflect their deep connection to the desert and its natural processes.

This cultural heritage is not only crucial for the identity and well-being of these communities but also contributes to the broader understanding of Australia’s indigenous history and the role of Aboriginal people in shaping the continent’s landscapes.

Today, the indigenous communities of the Great Victoria Desert continue to uphold their traditional ways of life while also engaging with modern challenges, such as land rights, cultural preservation, and sustainable development.

5. Exploration and Settlement

Ernest Giles, an intrepid British explorer, embarked on a mission to traverse the uncharted expanses of the Great Victoria Desert in 1875. He named the desert after the then-reigning monarch, Queen Victoria.

However, the Great Victoria Desert in Australia has been home to aboriginal people for millennia, long before the arrival of Europeans. The Spinifex People, also known as the Pila Nguru people, have lived in the Tjuntjuntjara area for approximately 25,000 years, with some current families tracing their roots back 600 generations.

As the traditional owners of the land, they have a deep connection to the area and its natural resources. Sadly, in the 1950s, the British and Australian governments chose the region for nuclear testing, and many of the Pila Nguru people were forced to leave their homes.

This displacement caused them to lose their traditional way of life, and they were relocated to settlements further south. However, some of the surviving families returned to their native lands in the 1980s.

6. Conservation and Environmental Issues

The Great Victoria Desert, while seemingly inhospitable, is a fragile and unique ecosystem that faces a number of conservation and environmental challenges. Efforts to protect the region’s biodiversity, cultural heritage, and natural resources are crucial to ensure the long-term survival of this extraordinary landscape and its inhabitants.

There are several protected areas within the Great Victoria Desert, including the Mamungari Conservation Park in South Australia and the Great Victoria Desert Nature Reserve in Western Australia.

These parks aim to preserve the unique flora and fauna of the region, as well as protect the cultural heritage of the indigenous communities who have lived in the area for thousands of years.

One of the significant environmental challenges facing the Great Victoria Desert is the impact of invasive species, such as rabbits, camels, and feral cats. These non-native animals can have detrimental effects on the desert’s ecosystem as they compete with native species for resources, spread diseases, and disrupt natural predator-prey relationships.

The potential effects of climate change on the Great Victoria Desert ecosystem are another cause for concern. Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events can have significant impacts on the desert’s flora and fauna, altering the distribution of species and potentially leading to localized extinctions.

7. Tourism and Recreation

The Great Victoria Desert offers a range of outdoor activities for adventurous travelers seeking to experience its unique landscapes, flora, and fauna. From 4WD tours to hiking and birdwatching, there is no shortage of opportunities for exploration and adventure in this vast and captivating region.

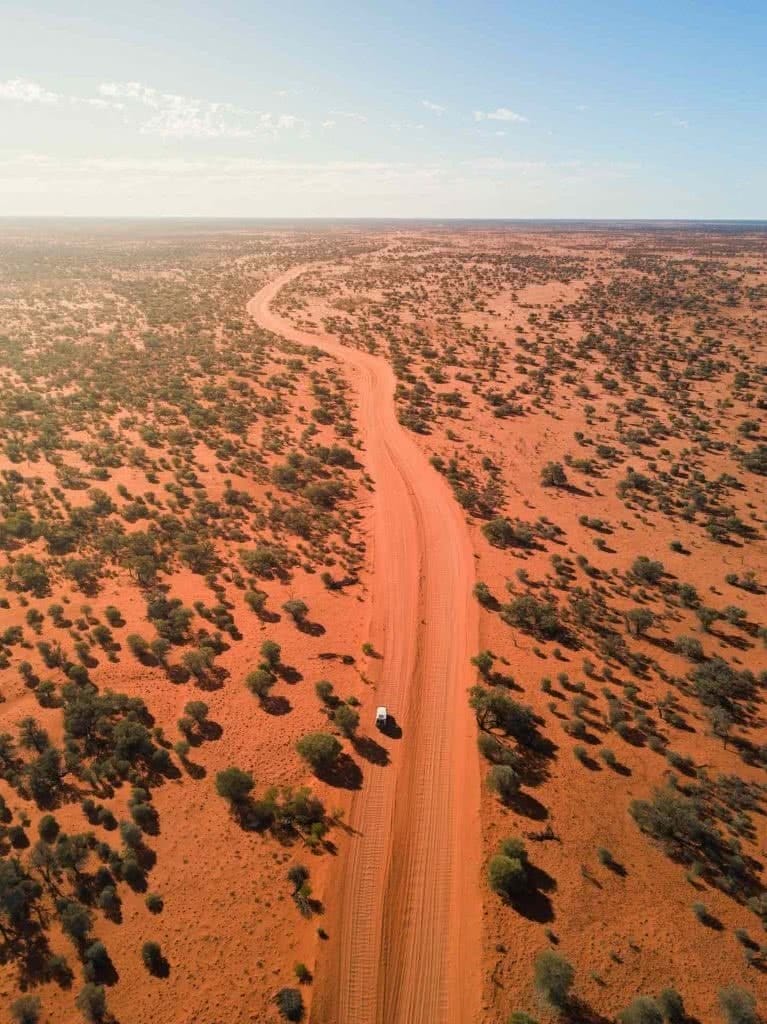

- 4WD Tours : One of the most popular ways to explore the Great Victoria Desert is by embarking on a 4WD tour. These off-road adventures allow travelers to access remote areas of the desert while guided by experienced drivers who possess expert knowledge of the terrain and local conditions.

- Hiking and Birdwatching: For those who prefer a slower pace, hiking is an excellent way to immerse oneself in the desert’s unique beauty. Numerous trails and tracks provide opportunities to explore diverse landscapes, from vast sand dunes to rocky outcrops and ephemeral waterholes.

- Aboriginal Cultural Experiences: Visitors to the Great Victoria Desert also have the opportunity to learn about the region’s rich Aboriginal culture through guided tours and cultural experiences. These activities provide insight into the traditional knowledge and practices of the desert’s indigenous inhabitants, as well as their enduring connection to the land.

Popular Attractions

There are several notable attractions within the Great Victoria Desert that should not be missed by travelers, including:

- The Anne Beadell Highway : A remote 4WD track that traverses the desert, the Anne Beadell Highway is an iconic route for off-road enthusiasts. This challenging track stretches over 1,300 kilometers and takes travelers through a variety of landscapes, from sand dunes to salt lakes and rocky outcrops.

- The Neale Junction : A historic meeting point of two outback tracks, the Neale Junction marks the intersection of the Anne Beadell Highway and the Connie Sue Highway. This remote location is a popular stop for travelers, offering a chance to rest and reflect on the vastness of the desert.

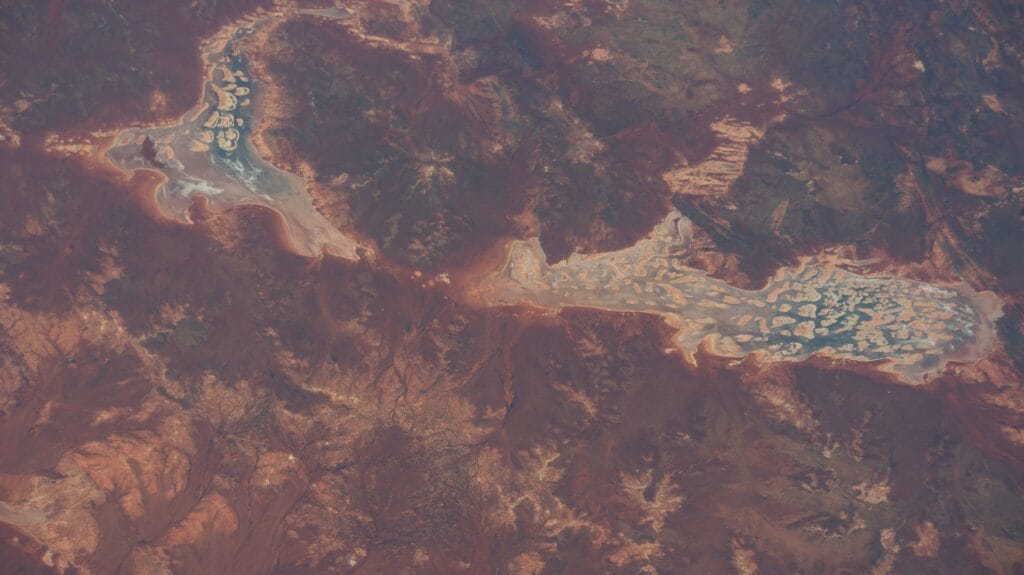

- The Serpentine Lakes : This series of salt lakes provide a unique landscape for photography enthusiasts and nature lovers alike. The lakes’ striking appearance, with their serpentine shapes and brilliant white salt crusts, creates a surreal and otherworldly atmosphere that is sure to leave a lasting impression.

The Great Victoria Desert is a vast and fascinating region, rich in natural beauty, unique wildlife, and cultural heritage. Its challenging environment has shaped the lives of its indigenous inhabitants and inspired generations of explorers and settlers.

The Great Victoria Desert is an ideal destination if you are searching for a unique, adventurous, and unforgettable travel experience.

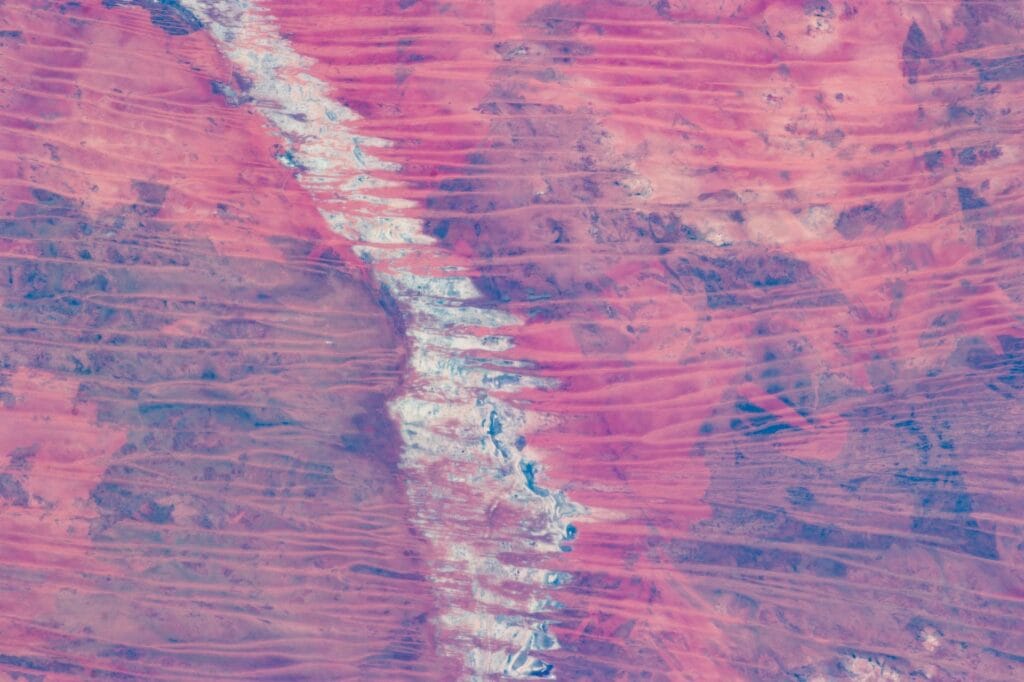

Featured Image by: Marian Deschain , CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Related Posts:

- Family & Relationships

- Fashion & Lifestyle

- Health & Fitness

- Home & Décor

- Kitchen & Cooking

- – Blog

The Great Victoria Desert – Nature | Culture | Adventure

- by Rachel Truman

Spanning over a vast area in Western Australia and South Australia, the Great Victoria Desert is one of the top largest deserts in the country. Despite its harsh and unforgiving climate, this arid expanse contains a surprising diversity of plant and animal life that has adapted to survive in the extreme conditions. The desert is home to a variety of unique flora such as spinifex, mulga, and mallee scrub, which provide habitat for animals like lizards, snakes, and small marsupials.

Although largely uninhabited by humans, the Great Victoria Desert Nature Reserve holds a wealth of Aboriginal history and culture, with sacred sites and rock art scattered throughout. This expansive wilderness contains natural wonders waiting to be explored.

This article will highlight some of the most fascinating aspects of this iconic Australian outback environment, from its breathtaking landscapes to its resilient inhabitants. The Great Victoria Desert never ceases to amaze.

Table of Contents

Where is the Great Victoria Desert?

The Great Victoria Desert, Australia’s largest desert and the eighth largest in the world is situated in the central and western regions of Australia. Covering an expansive area of approximately 422,466 square kilometers (163,115.035 square miles), this arid landscape spans across two Australian states: South Australia and Western Australia. The desert extends from the central to the western part of the continent, presenting a vast and remote expanse of arid land that captivates adventurers, scientists, and travelers alike.

Geography and Size

The Great Victoria Desert’s geography is characterized by vast stretches of arid land, sandy dunes, grasslands, and salt lakes. Dominated by open woodlands, including vegetation such as eucalyptus mulga, hummock grass understorey, and various shrubs, the desert showcases a unique and diverse topography. It is renowned for its immense size, making it the largest desert in Australia and a prominent feature in the southern rangelands of Western Australia.

The sheer magnitude of the desert, extending over 700 kilometers from west to east, contributes to its status as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. The Great Victoria Desert location, marked by its expansiveness and remoteness, adds to its allure as a pristine and untouched natural landscape.

Climate and Weather

Characterized by abiotic conditions, the Great Victoria Desert climate and weather shape its unique ecosystems. With low rainfall and high temperatures, the environment experiences extreme fluctuations. Annual precipitation averages between 200 to 250 millimeters, contributing to the scarcity of water resources. Summer temperatures frequently soar to 40 degrees Celsius, creating an environment of intense sunlight, rapid evaporation, and extremely dry air.

How Was the Great Victoria Desert Formed?

The formation of the Great Victoria Desert is a result of geological and climatic processes that have shaped the Australian continent over millions of years. Here is an overview of the key factors contributing to the formation of the Great Victoria Desert:

- Tectonic Activity: The Australian continent has been influenced by tectonic movements over geological time scales. The gradual drifting of the Australian tectonic plate and its interactions with neighboring plates played a role in shaping the landscape.

- Erosion and Uplift: The desert’s topography has been shaped by processes of erosion and uplift. Various geological forces, including wind and water erosion, as well as tectonic uplift, have contributed to the creation of distinct landforms within the Great Victoria Desert.

- Climate Changes: Changes in climate over epochs have significantly influenced the desert’s formation. Australia, as a continent, has experienced fluctuations in climate, with periods of aridity leading to the development of extensive arid regions.

- Regularity of Rainfall: The Great Victoria Desert is characterized by low and unpredictable rainfall. The arid climate, with an annual precipitation ranging from 200 to 250 millimeters (8 to 10 inches), has limited the growth of vegetation and contributed to the arid nature of the landscape.

- Evolution of Flora and Fauna: The flora and fauna within the Great Victoria Desert have adapted to the challenging environment shaped by arid conditions. The evolution of specific plant and animal species, such as spinifex grass, acacia shrubs, and various desert-adapted animals, reflects the long-term influence of climatic factors.

- Sand Dunes and Salt Lakes: The desert’s topographical features, including extensive sand dunes and salt lakes, are a result of aeolian processes (wind-related) and variations in salt deposition. These features contribute to the unique and visually striking landscapes within the Great Victoria Desert.

- Human Impact: While natural processes played a significant role in the desert’s formation, human activities, such as Indigenous land management practices, have also contributed to shaping the landscape over thousands of years.

Flora and Fauna

Contrary to expectations, the Great Victoria Desert hosts a diverse range of plant and animal species, each uniquely adapted to survive in this challenging environment.

What Plants Reside in the Great Victoria Desert?

Spinifex grass, acacia shrubs, and eucalyptus trees dominate the vegetation. Spinifex grass, with its deep roots, forms dense hummocks providing an essential habitat for small animals and reptiles. Acacia shrubs, known as wattles, showcase adaptability to arid conditions, while eucalyptus trees thrive along watercourses, supporting native bird and animal species.

What Animals Live in the Great Victoria Desert?

You’ll come across a variety of animals in the Great Victoria Desert as it is home to different lizard species, including the at-risk great desert skink and the Central Ranges taipan. Marsupials like the sandhill dunnart and the crest-tailed mulgara have adapted to the challenging terrain. Some species, like the southern marsupial mole and the water-holding frog, employ sand-digging strategies for survival. Predators include dingoes, perenties, and the formidable sand goanna. The avian population features unique species such as the chestnut-breasted whiteface and the malleefowl.

Threatened Species

Several species in the Great Victoria Desert face endangerment, including the sandhill dunnart, southern marsupial mole, malleefowl, great desert skink, rock wallabies, and bilbies. The delicate balance of this ecosystem requires concerted conservation efforts.

Indigenous People and Culture

The Great Victoria Desert is the traditional home of indigenous groups such as the Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara, and Ngaanyatjarra peoples. With a history spanning thousands of years, these communities maintain a profound connection to the land. Traditional practices, including hunting, gathering, and controlled fire use for land management, have shaped both the landscape and the indigenous way of life. The rich cultural heritage, expressed through stories, ceremonies, and art, reflects a deep connection to the desert’s natural processes.

Conservation and Environmental Issues

Preserving the delicate balance of the Great Victoria Desert is crucial for its biodiversity, cultural heritage, and natural resources. Protected areas, such as the Mamungari Conservation Park and Great Victoria Desert Nature Reserve, aim to safeguard flora, fauna, and indigenous cultural practices. Environmental challenges, including invasive species like rabbits, camels, and feral cats, pose a threat to the ecosystem. Additionally, climate change impacts, such as rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns, demand attention for the long-term sustainability of this unique landscape.

Tourism and Recreation – Explore the Great Desert

For those seeking adventure and an immersive experience, the Great Victoria Desert offers a range of outdoor activities. 4WD tours, guided by experienced drivers, provide access to remote areas. Hiking allows exploration of diverse landscapes, from sand dunes to rocky outcrops. Aboriginal cultural experiences provide insights into traditional knowledge and practices. Notable attractions, including the Anne Beadell Highway, Neale Junction, and the Serpentine Lakes, showcase the diverse and captivating features of the desert.

Additionally, visitors have a plethora of activities to indulge in within the Great Victoria Desert:

- Travel Routes: Drive the 1,325-kilometer Anne Beadell Highway from east to west, visiting Kirgella Rocks, Queen Victoria Springs, and Plumridge Lakes Nature Reserve.

- Exploration: Hike around the Kirgella Rocks for a closer experience of the desert’s unique features.

- Recreation: Engage in thrilling activities such as sandboarding, ATV riding, or horseback riding to add an adventurous touch to your visit.

- Aerial Perspective: Experience the breathtaking landscape from above through activities like hang gliding, providing a unique vantage point of the desert’s vastness.

Tour operators offer multi-day tour packages, catering to diverse preferences. To make the most of your visit, allocate at least four days for the tour. Given the vastness of the land and the myriad of activities and sites, a weekend trip might not suffice. Camping and motorbike tours emerge as popular choices among nature enthusiasts.

The top 3 recommended activities include ATV riding, hiking, and horseback riding. The best time to travel is in January when the average daily temperature is 95 degrees Fahrenheit, offering warm conditions. In contrast, July is considered the least favorable month due to freezing temperatures during the winter months.

Victoria Desert Trip Guide

As with any trip, it’s important to pack appropriately for the climate and activities you’ll be doing. Here are some tips on what to bring:

- Clothing: The Great Victoria Desert can get very hot during the day and cold at night, so it’s important to pack clothing that can accommodate both extremes. Lightweight, breathable clothing is best for the daytime, while warm layers are necessary for cooler nights. Don’t forget a hat and sunglasses to protect yourself from the sun.

- Footwear: Comfortable, sturdy shoes are a must for exploring the desert. Hiking boots or sneakers with good traction are recommended.

- Water: It’s essential to stay hydrated in the desert, so bring plenty of water with you. A reusable water bottle is a great option to reduce waste.

- Sunscreen and Insect Repellent: Protect your skin from the harsh sun and pesky bugs with sunscreen and insect repellent.

- First Aid Kit: It’s always a good idea to have a basic first aid kit on hand in case of any accidents or injuries.

- Navigation Tools: The Great Victoria Desert is vast and can be easy to get lost in, so bring a map, compass, or GPS device to help you navigate.

- Camping Gear: If you plan on camping in the desert, make sure to bring a sturdy tent, sleeping bag, and camping stove.

By packing these essentials, you’ll be well-prepared for a safe and enjoyable trip to the Great Victoria Desert. Remember to always respect the environment and follow Leave No Trace principles to help preserve this unique natural wonder for future generations.

Final Thoughts

The Great Victoria Desert represents one of the last great wildernesses on the planet. This vast and remote landscape contains a diversity of natural wonders for those willing to venture into its depths. While its harsh climate and isolation present challenges, the rewards come in the form of stunning vistas, unique wildlife encounters, and the humbling experience of Australia’s expansive outback.

For the intrepid traveler, a journey through the Great Victoria Desert promises adventure, insight into indigenous culture, and an appreciation for the resilient lifeforms that endure in this iconic desert environment. Though arid and extreme, the beauty and fascination of this desert will continue to draw travelers to unlock its mysteries and embrace its extremes.

Who is the Great Victoria Desert named after?

The Great Victoria Desert earned its name from British explorer Ernest Giles, who embarked on an expedition in 1875 and named the desert in honor of Queen Victoria, the reigning monarch at the time. This vast arid landscape, stretching across South Australia and Western Australia, stands as a testament to the historical exploration of the Australian continent.

Is Uluru in the Great Victoria Desert?

No, Uluru, also known as Ayers Rock, is not situated in the Great Victoria Desert. Uluru is located in the Northern Territory of Australia, specifically in Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. The Great Victoria Desert, although expansive and captivating, is geographically distinct, spanning across parts of South Australia and Western Australia.

How old is the Great Victoria Desert?

Determining the exact age of the Great Victoria Desert is challenging due to its gradual formation over millions of years through geological and climatic processes. However, indigenous communities like the Pila Nguru people have a history of approximately 25,000 years in the region, showcasing the enduring connection between humans and this ancient Australian landscape. Explore the wonders of the Great Victoria Desert with our comprehensive guide. Discover its geography, climate, flora, fauna, and more.

As a freelance journalist, copywriter, and editor, Rachel Truman crafts compelling stories across travel, food, family, lifestyle, and B2B. With a keen eye for detail, Rachel specializes in creating engaging branded content, making every word an adventure

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- The Great Victoria Desert

- The Great Victoria Desert (GVD) is Australia’s largest dune desert and the seventh-largest desert in the world.

- It was named after Queen Victoria in 1875 by a team led by Australian explorer, Ernest Giles.

- The climate of the GVD bioregion is arid with warm to extremely hot and humid summers.

- Some threatened mammals live in this region like the sandhill dunnart, the Southern marsupial mole, and the malleefowl.

The Great Victoria Desert (GVD) is Australia’s largest dune desert and the seventh- largest desert in the world . It spans over 700 kilometers from west to east and covers a total area of 350,000 square kilometers. This huge desert is considered an arid land with areas that go from Western to South Australia. It was named after a British queen, Queen Victoria, in 1875 by a team led by Australian explorer, Ernest Giles.

Where Is The Great Victoria Desert?

- Plants And Animals

- Endangered Species

Historical Role

Human settlements, modern significance, environmental threats and territorial disputes.

Australia’s biggest desert considered a UNESCO Biosphere reserve is located in the southern rangelands of Western Australia and stretches into the Western side of South Australia. It is located North of the Nullarbor Plain and is surrounded by other smaller deserts and ranges like the Darling Range, the Gibson Desert, Hamersley Range, and the Barrow Range.

Topography Of The Great Victoria Desert

Australia’s largest desert consists of many small sandhills, grasslands, and salt lakes. There is very little room for farming and grazing and the entire vicinity is a protected area.

It is so huge it would take several days for a person to cross it. Several parks and reserves are located here including the Great Victoria Desert Nature Reserve, the Flora and Fauna Conservation Park, and the Nullarbor National Park.

The Climate Of The Great Victoria Desert

The climate of the GVD bioregion is arid with warm to extremely hot and humid summers. Daytime temperatures at this time range between 32 to 40 °C (90 to 104 °F). Summer months are from December and February. Winter, on the other hand, happens Between June and August and is relatively still warm compared to other parts of Australia with temperatures that range between 20.4 and 22.7°C in the daytime.

The GVD also receives little rain that’s variable and unpredictable. Annual rainfall can average somewhere below 150 mm to over 250 mm. Because water is so scarce it is such a precious resource and only certain species of plants and animals can survive there.

Plants And Animals Of The Great Victoria Desert

Most of the Great Victoria Desert is covered by open woodlands with vegetation including eucalyptus mulga ( Acacia aneura ), a hummock grass understorey ( Triodia spp. , largely T. basedownii ), and shrubs ( Maireana sedifolia , Dodenaea attenuata ) according to WWF .

Three species of gum tree thrive in GVD, Eucalyptus gongylocarpa, E. socialis and E. pyriformis . The first is also known as the desert gum and typically grows among the sand in the Great Victoria Desert. A small tree called mulga also grows in the area stretching across the desert covering hundreds of miles.

The GVD has an exceptionally high diversity of reptiles according to WWF. One of which is the endangered great desert skink which was thought to be extinct in South Australia until its rediscovery in 1998. There are over a hundred species of reptiles in this arid area. Throughout different parts of the desert, there are various species of lizards.

Other animals that call the Great Victoria Desert home are rock wallabies that are nearing extinction. They live on the jagged cliffs in the desert and are well equipped for life on the rocky hillside because of their short powerful legs. There are also many bilbies in the area which look like large mice with big rabbit ears. Many camels are also found here although unlike those found in other countries, these are feral and are considered 'pests' since they damage vegetation. Their numbers all around Australia have now reached a million and their population increases 8% yearly.

The GVD is also home to several predators like the dingo, the perentie, as well as feral cats, and foxes. There are also some hoop snakes known as Bandy Bandy in the area which only come up to the ground at night to hunt for food.

Endangered Species

Some threatened mammals also live in this region like the sandhill dunnart, the Southern marsupial mole, and the malleefowl. The Southern marsupial mole is an interestingly quirky creature. The tiny marsupial is covered all over with silky and thick cream-colored fur, have vestigial eyes, and no external ear opening. They are also known as “blind sand burrowers” and they live mostly underground coming up occasionally to feed on geckoes and insects.

The malleefowl, on the other hand, also known as ‘Nganamara’, is a ground-dwelling bird that’s about the size of a domestic chicken. They create mounds and keep eggs there with their mate which they often stay with for the rest of their lives. There are only a few of them due to extensive clearing of vegetation for mining and exploration activities as well as overgrazing by feral animals.

The Great Victoria Desert was named after the then-ruling United Kingdom monarch, Queen Victoria, by explorer Ernest Giles. Giles was the first ever explorer to crisscross it with his team on camels, doing so from May to November of 1875, according to South Australian History. David Lindsey was the next explorer to have crossed the Great Victoria Desert from North to South in 1891. Frank Hann then followed, traversing the desert from 1903 to 1908 in search of pastures suited for grazing and the presence of gold deposits. Len Beadell, a surveyor for the Australian Army, also crossed the desert as he worked in the building of the Anne Beadell Highway from 1953 to 1960. According to Australian Geographic, aboriginal communities have lived in the Great Victoria Desert for at least 15,000 years. Oak Valley, Watarru, and Walalkara are the parts of the desert where the largest of these communities live.

Long before the Europeans came to this part of Australia, aboriginal people have been calling the Great Victoria Desert home. The people of Tjuntjuntjara, for instance, known today as the Spinifex People have inhabited the area for 25,000 years. Current Spinifex families here go back to as far as 600 generations.

Also known as the Pila Nguru people, they are considered the traditional owners of the land. Although in the 1950s many of them were driven away from their home. British and Australian governments chose the area near their settlements as the site for nuclear testing. Many of them moved out of their native lands and away from their traditional way of life. They were transferred to settlements further down South. Many of the surviving families moving back to their native lands in the 80s.

Due to the harsh climate and geographical isolation, much of the settlers there have remained relatively undisturbed ever since. Aboriginal populations in this area are also growing.

In Australia, according to the country’s government, desert tourism influences nearly all other the industries in the Great Victoria region, including their infrastructure and the quality of life among the populations there. Tours to deserts like the Great Victoria Desert contribute $94.8 million daily to the economy. This desert is endowed with unique flora and fauna, and many tourists and researchers visit here just to see them. Other tourists are more allured by the opportunity yo get to experience the aboriginal culture.

Weapons testing ( especially nuclear) and mining are the main threats to the Great Victoria Desert's biodiversity, according to World Wildlife Fund. They pollute and cause vegetation to be cleared and fragmented, thereby destroying the desert’s ecological balance. Past nuclear tests conducted there between 1953 and 1963 left sections of the deserts in Maralinga and Emu contaminated with radionuclides. Plutonium-239 deposits in the long term also threaten the health of animals in the desert if inhaled, due to their long radioactive half-lives. Road building and vehicles being driven off of designated tracks also disrupt the desert ecosystems. As such, permits for off-trail drives are needed. Introduced animals like camels, rabbits, and house mice, which increase during rains, also feed on, and thereby take away from, native vegetation fed on by native mammals of the Great Victoria Desert.

- World Geography

More in World Geography

Pantanal, Brazil

What Is A Plateau?

Regions Of Europe

Transcontinental Countries Of The World

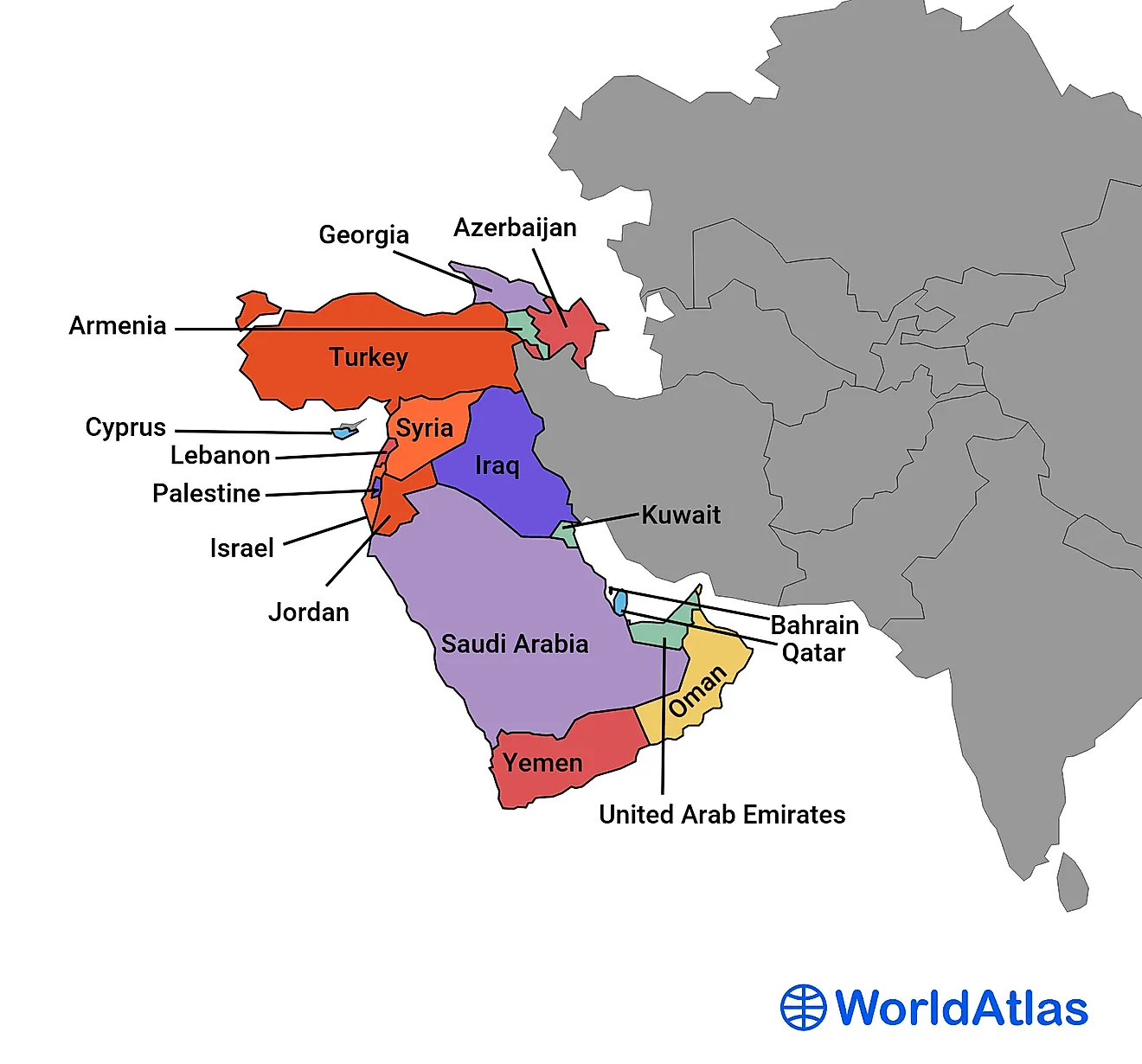

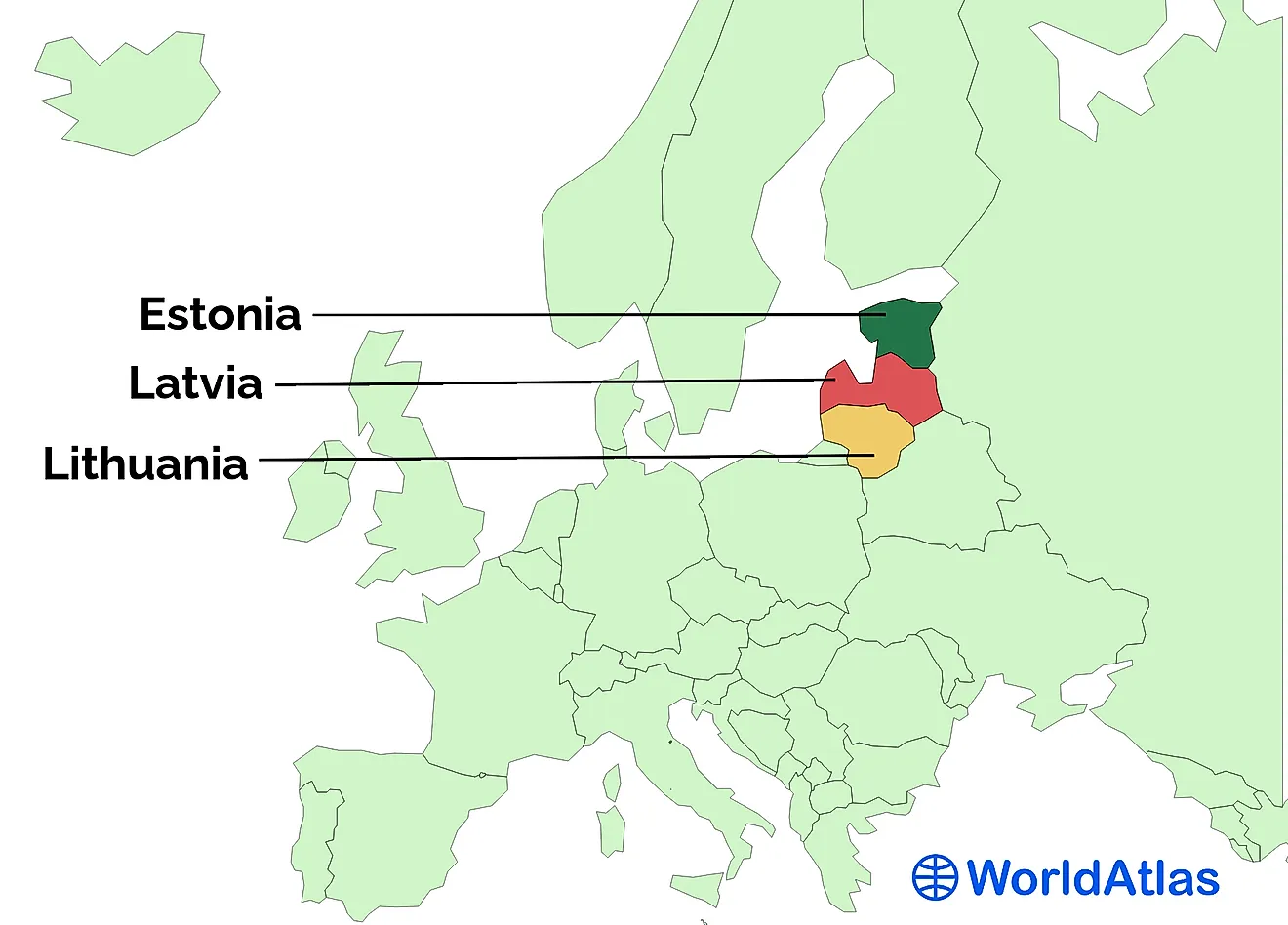

Western Asia

Is Greenland A Country?

Sinai Peninsula

Baltic States

- Science & Environment

History & Culture

- Opinion & Analysis

- Destinations

- Activity Central

- Creature Features

- Earth Heroes

- Survival Guides

- Travel with AG

- Travel Articles

- About the Australian Geographic Society

- AG Society News

- Sponsorship

- Fundraising

- Australian Geographic Society Expeditions

- Sponsorship news

- Our Country Immersive Experience

- AG Nature Photographer of the Year

- Web Stories

- Adventure Instagram

Desert delight

For five days I’ve been travelling along the straight line of the 1325km-long Anne Beadell Highway. This somewhat grandly named – but deteriorating – bush track stretches from the opal town of Coober Pedy in South Australia to Laverton in the Western Australian Goldfields. Along the way it traverses the Great Victoria Desert (GVD), which straddles the border between SA and WA. With a staggering size of more than 400,000sq.km – about twice the size of Great Britain – the GVD is Australia’s largest desert, covering about 5 per cent of the continent.

The term “desert” usually connotes images of dry, barren landscapes, recalling harsh and desolate wastelands. But so far these clichés don’t relate. The heavily corrugated and intermittently washed-out Anne Beadell leads through surprisingly dense vegetation, contradicting the common wisdom that deserts are characterised by a lack of plants, notably trees.

Andrew Dwyer, owner of the Diamantina Touring Company, with whom I’m travelling, has been roaming Australia’s deserts for 36 years. The GVD, named after Queen Victoria in 1875, is his favourite. “The space, the solitude, the pristine nature, the location, and the fact that it is in between the [ranges of] Central Australia to the north and the Nullarbor to the south” make the GVD a very special place for him. For this experienced desert veteran, however, the GVD does not seem like a typical desert. “It’s an arid region,” he says, adding that dictionaries define deserts as “dry and lifeless” places. “There is nothing dry and lifeless about [this],” he adds.

A desert is typically defined as an area receiving less than 250mm of rain per year. Australia’s deserts sometimes exceed this due to uneven rainfall distribution. In the GVD, the average annual rainfall is low and irregular, ranging from 200 to 250mm. Thunderstorms, mostly in summer, are relatively common with, on average, 15 to 20 per year dumping moisture onto the parched land below.

Surprising vegetation

I had my first experience of the GVD driving the Googs Track from Ceduna, on the SA coast, to the Trans-Australian Railway at Malbooma, near Tarcoola, in outback SA. The Googs Track is bulldozed straight through an undulating expanse of mallee-covered dunes that roll and heave towards the horizon.

It’s a roller-coaster at the very south-eastern extremity of the GVD that’s a popular challenge for four-wheel-drive enthusiasts. What surprises me about it is the extent of vegetation. Often described as a “sea of mallee”, this section of the GVD is densely covered in these multi-stemmed eucalypt species. There is also an abundance of wildflowers. One of the show-off flowering shrubs in the area, the grass-leaf hakea, is in full bloom. Its clusters of bright- pink flower cones distract me from the – at times challenging – track. Carpets of daisies colour the understorey.

The Googs Track brutalises this desert’s rolling dunes by cutting straight through them. In contrast, the Anne Beadell Highway follows valleys between the long rows and rarely crosses them. Both routes reveal the true nature of the GVD. It’s Australia’s largest dune field, with long drifts aligned in a west–east direction. However, in a very real sense, it’s also a green desert, although it has no major watercourses except, perhaps, the saline Ponton Creek, which is located on the GVD’s southern extremity. There’s no permanent surface water, with rock holes and claypans scarce – although soaks do hold water during wet periods.

It’s only in sections cleared by bushfires or cultural burning that this ocean of sand is revealed. Everywhere else, plants, ranging from grasses such as Eragrostis eriopoda – ornamental woollybutt – to spinifex, and from stately trees to shrubs, cover the sand. The lofty perspective of a drone reveals thetree cover, while seemingly dense from a ground perspective, is actually quite sparse, with ample space between each tree.

And yet, the botanical stars here are trees. The rare and aptly named Christmas tree mulga surprises with its tall, conifer-like shape. The desert poplar, with its lush, silvery-green foliage, is a favourite for roaming camels but seems alien among the desert vegetation. The large-fruited Ooldea mallee, with its stunning clusters of yellow flowers, appears overly flamboyant for such a dry area. The western myall, often described as a bonsai on steroids, seduces with its gnarly and photogenic shapes.

Then there is the marble gum, the signature tree of the GVD, with its sometimes stately size and ghostly mottled bark. These magnificent eucalypts often sit on the crests of dunes and become steady companions as you traverse deeper into the desert. As with the spinifex grasses, these beautiful eucalypts begin to appear about four days into our traverse. On the Coober Pedy side of the GVD there are no marble gums.

Australia’s most biodiverse desert

It’s easy to initially dismiss the GVD as monotonous, because its real beauty isn’t immediately obvious…at least to the uninitiated. If your eyes are only set to panoramic views, you might get the impression of endless sameness. To see this desert’s real nature, you need to rid yourself of preconceptions of what a desert should look like. The GVD demands a deeper connection and a closer look before it reveals itself. Far from being uniform, this desert is defined by constant changes in vegetation. For Andrew, “it’s a virtual botanical garden”. “It’s the most biodiverse desert in Australia,” he says. “The extraordinary thing about the Great Victoria Desert is that it has so many different plant colonies. You’ve got the casuarina pauper forests over limestone, you’ve got the dune communities, you’ve got mallee and you’ve got these beautiful flowering eucalypts. It’s just so diverse.”

As if to underscore Andrew’s words, the desert throws in a surprise when we encounter dunes that localised rains have turned into flowering gardens. Contrasting with the deep-red sand, the colourful bouquets on display consist of masses of striking poached-egg daisies, delicate purple parakeelyas and small yellow button daisies. Far from being a barren wasteland, the GVD is a biologically rich bioregion, with a vast array of animals and plants that have adapted to the harsh conditions. While the vegetation is there for all to see, the fauna is much more secretive. Wildlife sightings during the day are sparse. We see the occasional feral camel family group, a brown falcon with a small snake in its talons, a mob of red kangaroos in the distance and, every now and then, a thorny devil.

The real picture of what populates this arid wonderland is revealed in the sand. A multitude of prints divulge the abundance of animal species in the GVD. Visitors with the skills to interpret these animal tracks might find prints made by several species of dunnarts, mice and kangaroos.

The desert’s reptile fauna is especially diverse. The GVD is considered one of the richest areas in the country for reptiles, with approximately 90 species living among the dunes. Snake and lizard tracks are common. Every now and then, beetle tracks and prints made by birds add to the picture. Some of the more common bird species are the brown falcon, crested pigeon, ringneck and mulga parrots, fairy-wrens, and honeyeaters. Bird enthusiasts can also expect to glimpse two of Australia’s most beautiful, yet elusive, bird species here: the scarlet-chested parrot and princess parrot .

A dark history

There is, however, another side to this ecologically largely intact wilderness. Three days into our journey, we deviate from the Anne Beadell Highway and follow a short, dusty track north. It leads through magnificent stands of mature western myall. Some are in full bloom, completely covered in yellow flowers. Then the trees stop and an undulating, sparsely vegetated area opens up, with grasses and bluebush stretching to the horizon. This is Emu Field.

Located about 260km by road west of Coober Pedy, this place has a dark history. In 1953 the British detonated two atomic bombs here, Totem I and II. Two concrete plinths mark ground zero and warn of radiation. Atomic glass – molten sand transformed into glass by the immense heat of the explosion – litters the ground. Barrel-sized concrete foundations that once held up scientific instruments and other items, as well as twisted metal, are some of the very few leftovers of a once extensive infrastructure. Nearby is the large claypan that served as an airport during the test operation. We stop at Observation Point, a lookout from where British scientists observed the two explosions on the horizon.

“The great dichotomy of the GVD is you’ve got this stunning nature, and yet most of the infrastructure was built to blow things up,” Andrew says. Large sections of the GVD are classified as the Woomera Prohibited Area and, to this day, a permit is required to enter it. The Anne Beadell Highway, our pathway through this enormous desert, was in fact constructed in connection with the rocket range projects at Woomera.

Only 180km south of Emu Field, on the southern edge of the GVD and within a few kilometres of the almost treeless plains of the Nullarbor, is Maralinga, the second atomic test site within this extraordinary desert.

Robin Grant Matthews is the site manager and the only permanent occupant of Maralinga Village. “Been coming to this place since 1972,” he says. “It’s my wife’s traditional land. Now that she is sadly passed away, I’m feeling really connected to the land through her.”

Robin’s interest in history drives him to explore the test sites. “The British left so many secrets here and I try to unravel them all,” he says, admitting that many of his questions about the site will remain forever unanswered. “Maralinga always will hold those secrets,” he says. “If you find something, nine out of 10times it opens a Pandora’s box of questions.”

His wife succumbed to cancer a while back, and Robin recently survived Hodgkin’s lymphoma. “It comes from this place,” he says, recalling how for years they’d dig through the dirt here and become covered in dust. Now he always carries a radiation monitor and carefully checks everything he unearths. One of his discoveries is a series of buried steel bunkers close to ground zero, where volunteers huddled during the detonations. Another relic of the test period is the heavy lead casing of a camera used to photograph the detonations.

Seven atomic bombs were detonated in Maralinga between 1956 and 1963. Taranaki was one of these test sites and was once considered the most contaminated site on earth. The contamination, however, stemmed not from the fall-out of the bombs but from so-called minor trials, which involved testing the performance of weapon components. Among other extremely toxic substances, plutonium was blown up and spread over a large area.

From the lofty perspective of a drone, the scale of Taranaki’s scarred landscape, where some 330,000 cubic metres of plutonium-contaminated soil was scraped off and buried deep in a massive pit, becomes visible. The effects of the detonations are still visible at the blast sites – the vegetation hasn’t recovered in the intervening 70 years. The sterilised ground is still stunting plant growth.

“I really believe it was necessary in one way, because Britain wanted to get into the nuclear arms race, but they came here and took this place over,” Robin says. “They said it was supposedly an uninhabited desert. But it wasn’t. Anangu people were walking around here. It’s a really bad piece of our history.”

More surprises

After our side-trip to Emu Field, we return to the Anne Beadell Highway and are once again swallowed up by the ever-changing vegetation of the GVD. There is an acute sense of remoteness now. Left and right of the track, untouched bush stretches to the horizon, giving the GVD great ecological integrity. Mark Shephard, author of The Great Victoria Desert – no longer in print – called this desert the “hidden jewel of Australia’s outback”. Apart from the excursion to Emu Field, other attractions are sparse. Two short detours interrupt our journey west – one to the crash site of a Goldfields Air Services plane that came down in 1993, and the other to the Serpentine Lakes, a series of claypans along an ancient river course.

A visit to two waterholes, the Mulga and Djindagara rock holes, and to an area with large stone arrangements, brings the area’s history of human occupation into focus. Despite being one of the most sparsely populated areas in Australia, the GVD has long been occupied by the people of Tjuntjuntjara, known today as the Spinifex People , or Anangu.

“People were always on the move,” Andrew says. “People would journey from the Musgrave Ranges south all the way to Ooldea Soak and other water points.” These water points – rock holes containing water – were vitally important in the otherwise waterless expanse. Scattered throughout the desert, they were linked by travelling routes, especially in the eastern half of the GVD.

On the western side – within the Anangu Tjutaku Indigenous Protected Area, which represents the latest step in the Spinifex People’s articulation of their traditional and cultural connection to, and ownership of, the region – is Ilkurlka roadhouse. This is the first tiny enclave we encounter after leaving Coober Pedy. Ilkurlka is owned by the Tjuntjuntjara community, which is based 130km south of the roadhouse.

Philip Merry, of English descent, is employed by the community as the manager of this lonely post, which some consider the most remote roadhouse in Australia. “I was fortunate to be allowed to work here,” Philip says. He’s used to isolation, having spent most of his working life roaming the vast Australian interior as a mineral explorer.

The roadhouse was built in 2003, funded by money paid as compensation following the nuclear tests. “We are in the centre of culturally very sensitive Country,” Philip says. In summer, when there is less to do at the roadhouse, he gets the chance to experience the beauty of the GVD and the culture of the Spinifex People. He’s been taken around rock holes, told stories about Country and seen bushcraft in action. He considers himself a truly lucky man to be given a glimpse, every now and then, of this ancient culture. For us, just travelling through, it stays a hidden world.

About 300km west of the roadhouse and close to the western extremity of the GVD, the landscape dramatically changes. We’ve now reached breakaway country. The most striking landmark is the rock bastion of Bishop Rileys Pulpit – a freestanding mesa, or flat-topped landform – surrounded by steep rock walls. From the top, the view reveals sparse vegetation. The overgrown dunes have disappeared. So have the marble gums and spinifex grasses. The ground is rocky and barren. Although the landscape is still not entirely devoid of vegetation, some of the terms often associated with deserts now finally apply here; it seems a harsh, bleak, parched and hostile place.

Floating first

Colour fills the skies above Northam, Western Australia, as the Top Guns of the balloon world chase glory in the Women’s World Hot Air Balloon Championship.

An unexpected Pacific paradise

Visiting Micronesia’s islands and atolls offers an unexpected rare glimpse into remote communities steeped in centuries-old cultural traditions.

Go beyond: the ultimate guide to outback travel

Exploring the outback is a rite of passage for adventurous Aussie families. Here’s all you need to know for a successful, safe and fun experience.

Watch Latest Web Stories

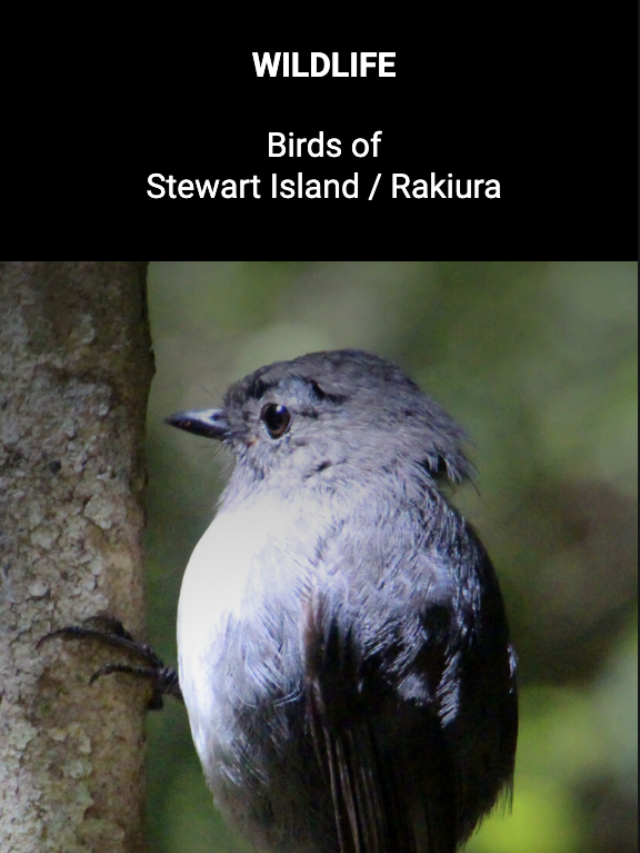

Birds of Stewart Island / Rakiura

Endangered fairy-wrens survive Kimberley floods

Australia’s sleepiest species

Great Victoria Desert

A large and expansive desert ecoregion of many small sandhills, grassland plains, gibber plains and salt lakes.

422,466 km²

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Top 3 Threats

- Feral animals

- Nuclear testing

Background – CC Attribution Share Alike 3.0 Unported – Marian Deschain, 2011 / Map – CC Attribution Share Alike 3.0 Unported – Hesperian, 2007

- Mamungari Conservation Park

- Tallaringa Conservation Park

- Yellabinna Regional Reserve

- Yeo Lake Nature Reserve

- Friends of Parks South Australia

- Friends of the Great Victoria Desert

- WA Parks and Wildlife Service Volunteers

Food and Homeware: The Brew

Environmental Consulting: Low Ecological Services

- Great Victoria Desert Biodiversity Trust

- Carbon Positive Australia

- Country Needs People

- desertSMART EcoFair

- 10 Deserts Project

- Adopt carbon farming practices on your land

- Avoid mass-farmed products (e.g. palm oil)

- Avoid the use of toxic chemicals

- Buy from local businesses

- Buy from long-lasting brands

- Compost edible and biodegradable waste

- Holiday locally (reduce your air-miles)

- Increase your local Indigenous knowledge

- Invest in ethical banks and institutions

- Keep your pets indoors at night

- Minimise unnecessary packaging and bags

- Plant native plants on your property

- Promote upcycling and reusing

- Recycle in your local area

- Reduce energy consumption at home

- Reduce your red meat consumption

- Switch to a renewable energy supply

- Use public transport as much as possible

- Vote for a clean and green future

- Watch and learn about local native wildlife

CANOPY LAYER

Plant Baarla ( Eucalyptus gongylocarpa ) and Ooldea Range Mallee ( Eucalyptus canescens ) if you have the space. To create habitat, consider installation of nestboxes for native birds and creating hollows in old, dead tree limbs.

SUB-CANOPY LAYER

Plant native sub-canopy trees like Ponton Creek Mallee ( Eucalyptus articulata ), Red Mallee ( Eucalyptus socialis ) and Belah ( Casuarina cristata ) or tall shrubs like Mulga ( Acacia aneura ) and Emu Tree ( Hakea francisiana ). To create habitat, consider installation of nestboxes for native birds and creating tree hollows in old, dead tree limbs.

SHRUB LAYER

Plant native shrubs that are hardy to desert conditions including Narrow-leaved Hop-bush ( Dodonaea attenuata ), Honeysuckle Grevillea ( Grevillea juncifolia ), Cactus Bossiaea ( Bossiaea walkeri ), Pin Bush ( Acacia nyssophylla ), Western Myall ( Acacia papyrocarpa ), Tar Bush ( Eremophila glabra ) and Sandhill Hibiscus ( Alyogyne pinoniana ). To create habitat, consider installing insect hotels, compost-heaps and bird-baths in this layer.

GROUND LAYER

Plant tufts of cottage-garden style herbs and grasses like Lobed Spinifex ( Triodia basedowii ), Ruby Saltbush ( Enchylaena tomentosa ), Davenport Daisy ( Lawrencella davenportii ), Annual Yellowtop ( Senecio gregorii ) and the stunning, profusely-flowering Cephalipterum drummondii . To create habitat, consider installing a pond or bog-garden with native aquatic and riparian plants, log-piles for sheltering amphibians and reptiles and leave areas of leaf-litter for important insects.

The Great Victoria Desert is a global hotspot for plants and animals that are adapted to the extremes of survival. Reptiles, desert plants and birds are all well-adapted to tolerate hot days, cold nights and little standing water. The ecoregion is home to intriguing mammals as well, although many species have been driven to extinction largely due to introduced predators like cats. Reptiles are particularly well represented with over 100 species recorded by scientists in the desert’s ecosystems. The ecoregion also contains large protected areas as well as important Indigenous Protected Areas and the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (or APY) lands.

Large sand dune and sand plain desert

Carle Thulka (Lake Maurice)

Mintabie Painted Desert

Native plant communities

Pearl Bluebush ( Maireana sedifolia )

Western Myall ( Acacia papyrocarpa )

Sand Goanna ( Varanus gouldii )

Greater Stick-nest Rat ( Leporillus conditor )

Chestnut-breasted Whiteface ( Aphelocephala pectoralis )

Mt Finke Grevillea ( Grevillea treueriana )

Lesser Stick-nest Rat ( Leporillus apicalis )

Long-tailed Hopping-mouse ( Notomys longicaudatus )

Lesser Bilby ( Macrotis leucura )

Keystone Relationships

The Pearl Bluebush is a succulent-like small bluish-white shrub that is one of the few desert plants to provide moisture to grazers. This species is vital as a source of protein and hydration to many native animals.

Life-support Systems

Air filtration, shade provision, soil retention, flood mitigation, bioremediation, pollinator support, healthy culture, healthy people, climate change, biodiversity is fundamental to a healthy planet and thriving communities, but the world's species are under tremendous threat..

Great Victoria Desert landscape

The South Australian section of the Great Victoria Desert (GVD) is one of nine distinct sub-landscapes in the Alinytjara Wiluṟara region. It is the largest desert in Australia, spanning over 700 kilometres from west to east. Its pristine, arid wilderness includes red sand dunes, stony plains and dry salt lakes. There is no permanent surface water, with scarce rockholes, claypans and soaks holding water only during wet periods. Within this landscape there are Aṉangu communities at Oak Valley, Watarru and Walalkara. The South Australian section of the GVD is co-managed by the Department for Environment and Water (DEW) and the Traditional Owners of these lands, with work on Country supported by the National Parks and Wildlife Service and the AW Landscape Board.

Key characteristics

- The largest desert in Australia, featuring red sand dunes, stony plains and dry salt lakes

- An area of significant conservation importance that is a Declared UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve

- A remarkably weed-free landscape compared to other parts of the state, with only eight species of weeds reported

Native plants and animals

- Many species of conservation significance, reflecting an area rich in flora and fauna

- 15 bird species with a conservation rating including the princess parrot, malleefowl and scarlet chested parrot

- 95 reptile species, of which 18 have conservation significance

This landscape attracts four-wheel drive tourists wanting to experience the beauty and challenges of travelling through this remote area. Access to this region requires a pass or permit . There is no access for the general public to the APY Lands, and no transit permits are allowed. Visitors should also be aware that there are safety issues specific to the region.

- One Earth Navigator

- Our Mission

- Meet the Team

- Advisor Network

- Partner With Us

- Reports & Financials

- Science Overview

- Solutions Framework

- Bioregions Framework

- Read Stories

- Watch Videos

- Explore Categories

- One Earth Contributors

- Discover your Bioregion

- On-the-ground Projects

Image credit: Courtesy of Marian Deschain

Great Victoria Desert

The ecoregion’s land area is provided in units of 1,000 hectares. The protection goal is the Global Safety Net (GSN1) area for the given ecoregion. The protection level indicates the percentage of the GSN goal that is currently protected on a scale of 0-10. N/A means data is not available at this time.

Bioregion: Greater Australian Interior Desert & Shrublands (AU7)

Realm: Australasia

Ecoregion Size (1000 ha):

Ecoregion ID:

Protection Goal:

Protection Level:

States: Australia

The Great Victoria Desert is a global hotspot for reptile diversity, with the colourful thorny devil ( Moloch horridus ) being one of the most spectacular. These largely yellow lizards acquire water from their ant diet and the morning dew that settles on their extraordinary dense and long thorns. Over 100 species of reptile have been documented, including numerous geckos, agamids, skinks, goannas, and elapid snakes. In the western reaches of the desert, up to 9 gecko species co-occur in the same site, utilizing a range of habitats from rocks and salt flats to sand ridges.

The flagship species of the Great Victoria Desert ecoregion is the chestnut-breasted whiteface. Image credit: Creative Commons

The desert is largely covered in open woodlands of Eucalyptus gongylocarpa , E. pyriformis , and E. socialis with a hummock grass understory ( Triodia spp., mainly T. basedownii ), mulga ( Acacia aneura ) with other grasses ( Aristida spp. and Plectrachne spp.), or belah ( Casuarina cristata ) with shrubs ( Maireana sedifolia , Dodenaea attenuata ). Gibber plains covered in varnished pebbles have little vegetation, though after abundant rains ephemeral Fabaceae, Compositae, and Amaranthaceae flowers cover the broad plains with swathes of color.

Many of the vertebrate species have relatively wide distributions, though the endangered chestnut-breasted whiteface ( Aphelocephala pectoralis ) has a relatively restricted range. The malleefowl ( Leipoa ocellata ) is an unusual ground bird occurs here. The little-known night or spinifex parrot ( Geopsittacus occidentalis ) is recorded here, as well. The great desert skink ( Egernia kintorei ) was rediscovered a few decades ago.

Sand goanna. Image credit: John Tann, Creative Commons

Mammals include the endangered sandhill dunnart ( Sminthopsis psammophila ), the endangered marsupial mole ( Notoryctes typhlops ), and the vulnerable mulgara ( Dasycercus cristicauda ). Several mammals have been lost or extirpated, including the the pig-footed bandicoot ( Chaeropus ecaudatus ), short-tailed hopping mouse ( Notomys amplus ), long-tailed hopping mouse ( N. longicaudatus ), and lesser stick-nest rat ( Leporillus apicalis ). The greater stick-nest rat ( L. conditor ) still occurs.

Perentie. Image credit: Creative Commons

There are currently 9 threatened plant species, 10 threatened mammal species, 4 threatened bird species, and 1 threatened reptile species. Little grazing or clearing of habitat occurs, though military activities have brought in roads and radiation from nuclear tests in areas. Feral rabbits and mice degrade native vegetation and introduced foxes, feral cats, and dingos prey on native wildlife. Despite having the largest conservation areas in South Australia—the Unnamed Conservation Park (21,289 km 2 ) and the indigenous Pitjantjatjara lands—there are limited conservation actions. Other protected areas include Gibson Desert Nature Reserve, Mamungari Conservation Park, Warburton, Yulara, and Tallaringa Conservation Park.

The priority conservation actions for the next decade are to: 1) implement protection and recovery plans for the sandhill dunnart and malleefowl; 2) expand population control programs for feral cat, rabbit, and fox, especially within key protected areas; and 3) ensure that several Acacia corridors that cross the ecoregion remain intact.

Citations

- Cogger H. 2000. Reptiles and amphibians of Australia. Reed New Holland, Sydney, Australia.

- Greenslade P, L Joseph, R Barley (editors). 1986. The Great Victoria Desert . Nature Conservation Society of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia.

- Pianka ER. 1984. Diversity and adaptive radiations of Australian desert lizards. Pages 371-376 in M Archer, G Clayton (editors), Vertebrate zoogeography and evolution in Australasia . Hersperian Press, Perth, Australia.

Subscribe to receive monthly updates on climate solutions, environmental heroes, and the profound beauty and wonder of our shared planet Earth.

Explore the Bioregions

Want to learn more about the fascinating species, diverse ecosystems, and natural wonders of the Earth? Click the button below to launch One Earth's interactive navigator and discover your Bioregion!

This Is What Australia's Great Victoria Desert Is Known For (Besides Its Incredible Ecosystem)

The Great Victoria Desert is a mashup of historical and biological significance, starting with its unique environment.

The Great Victoria Desert (GVD) is one of the world’s prime spots for reptiles. It is both the hidden gem of Australia and the largest desert. It is one of the landmasses that has seen little to no development over the past decades. It consists mainly of playa lakes and dune fields. If you think that deserts are barren places with no signs of life , then do not be misconstrued by the “desert” in its name, as it does have some grasslands and the reptiles mentioned above. It is called a desert due to the lack of rainfall, not because it’s dry.

Reptilian And Wildlife Paradise

Certain species of reptiles can survive and thrive in deserts. Most common among them are snakes and lizards. The Great Victoria Desert is home to such animals and other types of reptiles that have adapted to the harsh conditions in the bioregion.

Thorny Devil

The Thorny Devil (Moloch horridus) is a lizard species that is endemic to the Australian desert. They cannot be found anywhere else. The Thorny Devil gets its name from its spiky skin that's used as a defense mechanism from predators. The spikes make them hard to be swallowed. Aside from the Thorny devil, the GVD is home to at least 100 species of geckos, skinks, snakes, and goannas.

The Various Mammals

Aside from reptiles, the GVD is home to mammals such as the sandhill dunnart, marsupial mole, and mulgara. A few of these plant, mammal, bird, and reptile species are endangered, which is why conservation efforts are in place. Predatory animals, like wild dogs and red foxes, threaten small and medium-sized animals in the desert.

RELATED: Crossing The Mighty Sahara Desert From Morocco To Senegal Via The Coastal Route

Flora and Fauna

The flora in the GVD has survived and thrived in harsh conditions with little to no rain. Only the hardiest plants can survive in such conditions. However, some of the plant species are in danger of extinction due to the worsening climate. The proliferation of buffelgrass (Cenchrus ciliaris) is a threat to the desert’s ecosystem because it spreads quite fast and can cause the rapid spread of bushfires.

Most famous plants:

- Mulga (Acacia aneura)

- Marble gum (Eucalyptus gongylocarpa)

- Large-fruited mallee (Eucalyptus youngiana)

History Of the Desert

The Great Victoria Desert is considered to be an unallocated land belonging to the Crown. Named after the then-reigning Queen Victoria at its discovery, the Great Victoria Desert is still largely untouched, at least until the late 1950s.

When people talk about the “Australian outback,” they’re most likely imagining the Great Victoria Desert. It is a vast arid land filled with exotic desert animals. It is a great place to go for a bit of adventure in the outback. There are parks and conservation sites where tourists can experience being one with the reptiles and possibly visit Aboriginal communities in some parts of the desert.

History of Nuclear Tests

Nuclear weapons testing was conducted in some regions of the Great Victoria Desert between 1956 and 1963. The weapons testing left certain parts of the desert contaminated with radioactive material. Because of the fallout from the blasts and the harmful effects of nuclear waste on the environment and people, these areas have been restricted and are now monitored.

Tours And Activities

Tour operators offer multi-day tour packages to visitors. For example, DACA Tours offers a 5-day motorbike tour of the desert starting at $2,805. To make a visit worthwhile, it is best to allow at least four days for the tour. It is an immense landmass with so many activities and sites that a weekend trip might not be enough! Camping and motorbike tours seem to be quite popular among nature-loving folks.

Top 3 activities:

- Horseback riding

Accommodations

Various types of accommodations surround The Great Victoria Desert. Therefore, it’s best to coordinate with tour operators for pickups and drop-offs after a full day of activities.

Desert Cave Hotel

Coober Pedy Experience

Mud Hut Motel

Best Time to Travel

January is the best time to visit the Great Victoria Desert because it’s the warmest time of the year. The average daily temperature is 95 degrees Fahrenheit. On the other hand, the worst time to visit is July. During the winter months, temperatures drop below the freezing point.

RELATED: This Is What It's Like To Hike Iceland's Volcanic Deserts, Known As The Highlands

Conservation Efforts

A significant portion of the Great Victoria has rightfully remained untouched. The desert has a unique ecosystem that protects the life that grows within it. The Mamungari Conservation Park is one of few conservation sites that continue to be protected due to being proclaimed a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO in 1977.

Some Aboriginal communities have been populating some of the more habitable areas of the desert. In 1991, the Maralinga Tjarutja and Pila Nguru groups were given a portion of the land by the government. While it is possible to visit the site, visitors are asked to present permits and other documents, which usually take weeks to process. Visitors have limited access to the park, often requiring the assistance of rangers and locals guides.

The Great Victoria Desert is a gem of the Australian tourism industry . Offering visitors a different way to engage with Mother Nature, will definitely feel a lot different from the usual beach vacation or holidays by the mountains. Nature and animal lovers might be surprised at what they find in the Great Victoria Desert. Unlike what your elementary science teacher would have taught you, deserts are not all barren and dry. Despite the arid climate, the Great Victoria Desert has protected various species of plants and animals. So have fun basking in the flora and fauna of the Great Victoria Desert.

NEXT: These Are The Most Beautiful Deserts In The World, And They're Far From Being Barren Wastelands

Discover the world

Where do you want to go :.

- Destinations

- Travelers & Locals

- Tours & Guides

320 Places and 555 Members

1250 Places and 2400 Members

2050 Places and 1500 Members

820 Places and 3400 Members

1050 Places and 2650 Members

1000 Places and 4340 Members

775 Places and 350 Members

800 Places and 750 Members

Join the Fun!

Create your travel profile. Meet like minded travelers. Share the places you love.

Tour Guide or Travel Agent?

Create a free profile and list your travel offers.

A Social Network Connecting Travelers and Locals

Travel is all about new experiences. No matter where you're going, Touristlink gives you opportunity to get a real feel of the culture. Meet up with a local for a coffee or beer, find travel companions to share the journey. Touristlink makes it easy to arrange your trip directly with the person organizing it. With over 50,000 tour operators and 150,000 travelers and locals signed up we are the largest social network connecting travelers and locals. Learn More >

Want to get started? Sign up and tell us where you're going. Share your trip plan with other travelers and locals and meet someone new or broadcast it to local guides to find the best deal or discover a tour you have not heard about. How it Works >

Post a Trip. Here is how it works

Travel is all about new experiences. No matter where you're going, Touristlink gives you opportunity to get a real feel of the culture. Meet up with a local for a coffee or beer, find travel companions to share the journey, or if you want arrange a tour with an independent guide. If you are looking to find a tour guide we will email your trip plan to relevant local guides and tour operators.

Post your trip

It takes just a few seconds to post your trip details to the Touristlink community.

Get Connected

Once it's posted locals and other travelers going the same place can see it and contact you. If you're looking for a guide or great travel deal will email your trip plan to the local tour operators so they may contact you.

Enjoy your Trip

Half of travel is meeting new and interesting people. Take a chance and see where Touristlink takes you. Get started.

Explore World

- Places To Visit

- Recreation / Outdoor

- Tourist Essentials

- Shopping / Nightlife

- Popular Destinations

- Towns & Villages

- Universities

- Skyscrapers

- Historic Houses

- States/Regions

- Heritage Sites

- Key Buildings

- Neighborhoods

- Famous Streets

- Plazas and Squares

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Learn more I agree

The Great Victoria Desert

Biodiversity trust, for all of us.

The Great Victoria Desert Biodiversity Trust is an environmental initiative which conserves and increases knowledge of biodiversity in the Great Victoria Desert.

The Great Victoria Desert Biodiversity Trust acknowledges and respects the land of indigenous people across the regio n , including elders past, pr esent and future .

About Our Trust

The trust was established by the tropicana joint venture as part of its offset strategy for the tropicana gold mine in western australia under the environmental protection and conservation act 1999. the trust has supported a variety of activities including desktop studies, field surveys and initiatives, and workshops, and projects that have community benefits to build capacity for people to manage country..

Workshops designed to increase knowledge.

MANAGING HABITATS

Spatial mapping and landscape trials in the GVD.

COMMUNITY SUPPORT

Support indigenous Rangers to attend NRM and indigenous forums, and manage country.

THREATENED SPECIES

Publicly available desktop studies, field surveys and initiatives.

Our Largest Desert

The Great Victoria Desert is Australia’s largest desert, covering an area of 418,800 km 2 within Western Australia and South Australia. Limited research and surveys have been conducted due to vast distances, inaccessibility and the high costs of mobilising people and equipment.

We Have the Energy to Impact Our Future, and We’re Doing Something About It

The Trust represents a new structure of offset delivery and operates as a unique partnership model between industry and government.

Happening Now

Always Was, Always Will Be

NAICDOC week 2020 The Trust recognises the importance of NAIDOC Week to celebrate the history, culture and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

GVD Landscape Conservation Initiative

The Landscape Conservation Initiative (LCI) objective is to reduce the extent and intensity of wildfires, and the impacts of...

Other Featured Initiatives

The Landscape Conservation Initiative (LCI) objective is to reduce the extent and intensity of wildfires, and the impacts of invasive animals on threatened...

Ground truthing Malleefowl mounds in the GVD

The Trust partnered with the National Malleefowl Recovery team to investigate LiDAR results

Get Involved Today

Learn more about partnering or getting involved, stay up to date.

Subscribe to stay up to date with news and events in the future.

Subscribe Now

Great Victoria Desert, Australia The Largest Desert In Australia

Great Victoria Desert

Size and Location History Climate Environment Individual Travel Tour Travel

About the Great Victoria Desert

Size and location.

The Great Victoria is the largest Australian desert . Its size is 424,400 km 2 (163,900 miles 2 ) according to most sources (though I've seen anything between 348,750 km 2 /134,655 miles 2 and 250,000 miles 2 ).

If the last number is correct then the Great Victoria Desert in Australia is the third largest desert in the world , after the Sahara and the Arabian Desert. If the first number is correct it would still make it to number eight on the list, followed by the Great Sandy Desert . Two Western Australian deserts in the top ten...

I didn't go out and measure. Either way the Great Victoria Desert is the largest desert in Australia. It spans over 700 km/435 miles from west to east , with the western part of it belonging to Western Australia , and the eastern part extending into South Australia . It can take several days to cross this desert, but more about that later.

On the borders of the Great Victoria Desert you find... more deserts. The Gibson in the north, the Little Sandy Desert to the north-west, the Nullarbor Plain in the South, and the Tirary and the Sturt Stony Desert to the east. Australia is a dry country once you leave the coasts. No wonder people always talk about "the Outback desert" (which I guess sums up all the Australian deserts...).

Return to top

The Great Victoria Desert in Australia was first crossed by the European explorer Ernest Giles in 1875 and named after Queen Victoria.

David Lindsey 's expedition crossed the area from north to south in 1891 . Lime Juice Camp is named to remind us of one of their mishaps: it was there that the party decided to have a celebration and open their supply of lime juice. It was mixed with whiskey and water in a galvanized tin, with the result that everybody became rather sick with zinc poisoning. Ah well...

The next explorer to leave his mark was Frank Hann , who was looking for pastoral lands and for gold in the area between 1903 and 1908. He named a few more places and features.

And last but not least there is the famous Len Beadell . He worked as a surveyor for the Australian army, and surveyed and build roads in the 1960s . If you read any of the many books he wrote about his time in the Great Victoria Desert then you can guess that the Anne Beadell Highway (named after his wife) is not exactly a highway...

The Great Victoria Desert receives only little rain, though not as little as one might suspect for a desert. The rainfall range is 200 - 250 mm a year, but the rain is unreliable. Southern parts receive some winter rainfall, further north the only water source are thunderstorms. And they are isolated and unpredictable.

The days in summer are hot, anything between 30 and 40°C (90 - 105F), but the dry heat is not as uncomfortable as the humid swelter of tropical Australia.

Winter temperatures range from a comfortable 20 to 25°C , but the nights can be freezing. And I do mean freezing, frosts are common .

Environment

Many people hear the word desert and expect endless sand dunes, or barren stony plains without vegetation. The Great Victoria Desert looks nothing like that. It's called a desert because there is little rain, not because it is dead or boring.

The amount of vegetation may surprise you . Australia has always been a dry continent, and the plants are well adapted to living with very little water. Not only marble gums, mulga and spinifex grass thrive here. You will find a huge variety of shrubs and smaller plants.

When it does rain the transformation is total. The desert bursts into bloom seemingly over night. Fields of wildflowers, accentuated with flowering grevilleas and acacias, yellows, whites and mauves against the red sands... I was lucky enough to cross the Great Victoria Desert after a big rain. The sight of the blooming desert is something I will never forget. (And the fact that I didn't have a camera on the trip is something I will never forgive myself...)

But even without any rain the Great Victoria Desert is a sight to behold. Rocks and ranges, caves and gorges, bluffs and breakaways... and wildlife, wildlife, wildlife .

But there are concerns also. Increasing tourist traffic may lead to habitat degeneration. And introduced feral animals are already impacting negatively. Donkeys, camels, rabbits... Chances are you'll see them, and they don't belong here.

Travel in the Great Victoria Desert

Individual travel.