10 Top-Rated Tourist Attractions in Nunavut

Written by Chloë Ernst and Bryan Dearsley Updated Sep 24, 2021

Officially established in 1999, Canada's Nunavut Territory is an administrative unit that was once part of the former Northwest Territories. And it's a very big place. Nunavut covers the whole of the eastern section of northern Canada and is a wonderful place to learn about the attractions, history, culture, nature, and best places to visit in Canada's Far North.

With an area of 1.9 million square kilometers, Nunavut is almost eight times the size of the United Kingdom and covers roughly one fifth of the total area of Canada. Its southern border is the 60th parallel, while the north extends to within about 800 kilometers of the North Pole. Most of the Territory is situated above the tree line, in a region of predominantly treeless tundra with dwarf shrubs, grasses, mosses, and lichens. Fjords cut deep inland from the coast.

Craft- and handicraft-based businesses have achieved extraordinary success here. Produced mainly in small workshops, the territory's leather goods, jewelry, and ivory work have great appeal for tourists visiting this and other regions of Canada . Hence, in addition to meeting the demand from the as-yet small number of tourists who visit the Far North, there is a lively "export trade" to the major tourist centers of the Canadian South, including Québec, Toronto, and Vancouver.

For inspiration and ideas about fun things to do when it comes to planning your northern Canadian adventure, refer often to our handy list of the top tourist attractions in Nunavut, Canada.

1. Baffin Island

2. auyuittuq national park, 4. ellesmere island, 5. quttinirpaaq national park, 6. sirmilik national park, 7. naujaat (repulse bay), 8. belcher islands, 9. pond inlet, 10. qaummaarviit territorial park, map of tourist attractions in nunavut.

With its breathtaking landscape, the warm hospitality of the Indigenous Inuit people, and the numerous opportunities for a unique holiday experience, Baffin Island is a strong draw for tourists. But it can hardly be said that it suffers from invasions of visitors, which is perfect for those who enjoy extremely remote, nature-inspired adventure travel.

The island is the fifth largest in the world, with a coastline and landscape that vary considerably. One of the best areas to visit is the island's eastern coast. It in fact shares a scenery that's very similar to Norway, with its steep fiords and small offshore islands, boasting a long, narrow alpine-like mountainous zone that reaches heights of 2,591 meters in Auyuittuq National Park on the Cumberland peninsula.

The main administrative town is Iqaluit on Frobisher Bay. The only way to get to the far north island is by air, which can be rather expensive. The cost of living is high, and the climate very "unfriendly," not to mention the hordes of insects that descend on the unfortunate traveler in summer. All in all, however, the region is perhaps somewhere for the travel specialist seeking a unique (and unforgettable) Canadian vacation adventure.

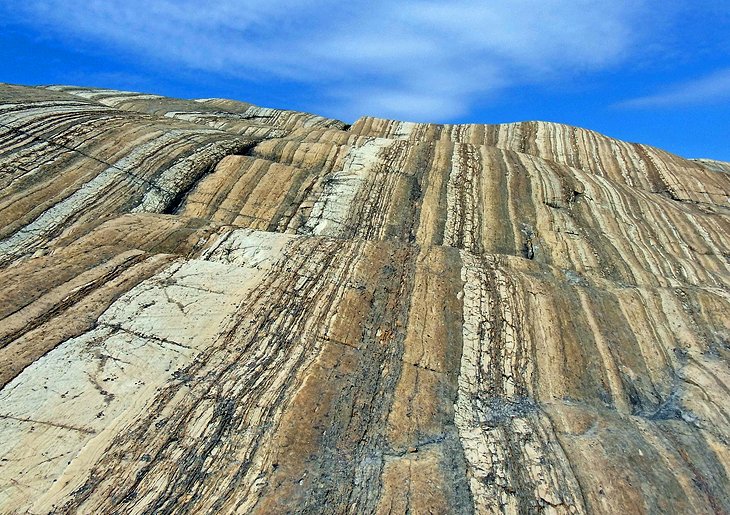

Literally translated as the "land where it never thaws," Auyuittuq National Park sits on the Cumberland Peninsula in the southeast of Baffin Island. The Penny Ice Cap , a remnant of Ice Age glaciations, takes up a large portion of the park.

The landscape is characterized by broad valleys and rugged mountains with vertical walls rising up to 1,200 meters in heigh. Of these, Mount Asgard is particularly impressive. Pangnirtung Pass is the best route through the park ending at the Pangnirtung Fiord.

Among extreme adventurers, the park is also known for its hiking. Of these, perhaps the best can be experienced on Mount Thor, a 1,675-meter-tall mountain peak that's known for its rock climbing. A word of caution: if you're contemplating such an adventure, you're first required to register with Parks Canada (see the website below for details).

Official site: www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/nu/auyuittuq

For many years, whalers, scientists, traders, and missionaries frequented Iqaluit, located at the end of Frobisher Bay. It was long known as the gateway to Baffin Island, and the Inuit name of Iqaluit means "many fish."

However, it was only in 1942, when the area was developed as a U.S. military airfield, that the community began to grow in size. Now the service and administrative center of the Baffin Region, Iqaluit is a modern town with a complete infrastructure and is home to the Nunavut Legislative Assembly, as well as hotels, schools, a hospital, and cathedral. There's also a weather and radio station, as well as a camping site.

Iqaluit is also where you'll find the Unikkaarvik Visitor Centre . This modern facility is a good place to gather information and learn more about this remarkable community. Also worth a visit is the Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum . Located in a former Hudson's Bay Company building, it's dedicated to the preservation of local Inuit art and culture.

Ellesmere Island lies in the extreme north of Canada, and is the second largest island - after Baffin Island - on the Canadian archipelago. It was from Ellesmere's Cape Columbia that American explorer Robert Peary set out in 1909 to walk to the North Pole.

In the extreme north of the island, you'll find Quttinirpaaq National Park . This spectacular mountainous and glaciated region has a number of hiking trails known to serious backpackers and adventure seekers. There's plenty of wildlife spotting opportunities here, too. Tourists often post pictures of sightings of seals and walrus, musk ox, wolves, arctic hare and, from a safe distance, polar bears.

At the south end of Ellesmere Island is Grise Fiord . This very small community boasts good hunting conditions and a beautiful Arctic landscape that can be viewed during canoe or snowmobile tours.

Located in the extreme north of Ellesmere Island is Quttinirpaaq National Park . This extremely mountainous and glaciated region is popular with hikers with a penchant for adventure, drawn here for its remoteness and a number of hiking trails that are known to serious backpackers.

In this predominantly dry Arctic climate, pockets of (relatively) warm and moist temperatures enable plants to grow and animals to exist, such as in the area around Lake Hazen. Here, you'll see everything from muskoxen, Peary caribou, arctic foxes and wolves, lemmings, and more than 30 species of birds. Most trips to Quttinirpaaq begin in Resolute Bay.

Official site: www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/nu/quttinirpaaq

Soaring mountains, rugged glaciers, and a wide variety of wildlife perfectly describe Sirmilik National Park. This beautifully rugged area is one of Canada's most remote and northern national parks, encompassing Bylot Island , Oliver Sound , and the Borden Peninsula .

The land is made up of beautiful mountains, glaciers, ice fields, and coastal lowlands. While some visitors come here for boating and kayaking adventures, it's important to note that the coast is normally not free of ice until mid-July. During ice break up and freeze up, travel to the park is not possible.

Official site: www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/nu/sirmilik

Reached only by plane, Naujaat - known as Repulse Bay up until 2015 before reverting to its native name - thrives on tourism. The big draw? Tourists come in search of land and sea adventures under the wisdom of Inuit tour guides.

The European chapter of this part of Canada's history opened in 1741, when Captain Henry Middleton sailed into the deep bay - known to the Inuit as "Naujaat" (gulls' nesting place) - in search of the Northwest Passage. In his disappointment of not finding the Arctic route, Middleton christened the place Repulse Bay.

Off the Hudson Bay coast lie the barren Belcher Islands, another potential tourist destination in Nunavut. Known to the Inuit as Sanikiluaq, the islands support polar bears and an abundance of marine life, including beluga whales and walruses in the surrounding waters.

While some adventure travelers come here to kayak, the Belcher Islands are, however, extremely remote and see very few visitors each year. There is an airstrip in Sanikiluaq , which services the area, but most who visit arrive by boat..

Set on the Baffin Island coast, Pond Inlet - or Mittimatalik in Inuit - is an Inuit village to the west of a rugged mountainous terrain. It attracts visitors for its natural beauty and culture, though the region is extremely remote and therefore costly to access.

One of the top tourist attractions in the community is the Nattinnak Centre . Part museum, part visitor center, the facility features fascinating displays on the history, geography, and wildlife of the region.

Qaummaarviit Territorial Park , once home to the Thule People and known as the "place that shines," is a rugged destination located on an island. Accessible by ski, dogsled, or snowmobile during the winter months, and by boat during the open-water season, here visitors can see the remains of the old Thule sod houses and artifacts dating back more than 750 years ago.

Also of interest are the many features that point to evidence of Inuit settlement and culture dating as far back as the 1600s. (Editor's Note: No camping is allowed, so plan to visit as part of a day trip to the island.)

More Related Articles on PlanetWare.com

Explore Canada's Great White North : While planning your Canada travel itinerary , be sure to consider some of the great attractions and destinations in the Far North. A few of our favorites include exploring Hudson Bay , known for its spectacular landscape and plentiful wildlife (yes, including polar bears), and the Northwest Territories , a vast region many times the size of the UK, which stretches toward the North Pole and is known for its abundant flora and fauna, as well as its capital city, Yellowknife , popular for its scenic drives and hikes.

More on Canada

Get up close to Arctic Wildlife

Nunavut is home to the Arctic Big Five . Namely Polar Bears, Musk Ox, Belugas, Walruses and the exclusive Narwhal. For these reasons, it is an incredible place to come and see the world’s most remarkable arctic animals and marine life in their natural habitat. Experiences and sightings depend greatly on season and location. Early spring offers opportunities to see Polar Bears roaming the Floe Edge. While summer and fall are usually the best times to spot Narwhals and Beluga in high Arctic locations such as Resolute Bay. Narwhals can also be spotted near the shores of Pond Inlet and Arctic Bay. Muskox and Caribou can be found in communities such as Baker Lake, Cambridge Bay, Gjoa Haven to name a few.

For the best chance to encounter wildlife, book yourself a tour with a local outfitter.

Explore the Great Outdoor

The landscape of Nunavut is unlike other parts of Canada. In Nunavut, there are no trees. Instead, the territory is made up of rolling plateaus, glacial troughs, fiords, and mountains that could rival the Rockies. It’s also the largest province or territory in Canada. For reference, if Nunavut were a country it would be the third largest. Open spaces for adventure are abundant in the Arctic. Make the most out of your trip and visit Auyuittuq National Park . There, you’ll be surrounded by rejuvenating mountains and glorious scenery. Feeling adventurous? Hike Mount Thor. Or enjoy the scenery by skidoo, dogsled, or even hot air balloon.

Discover Inuit Culture

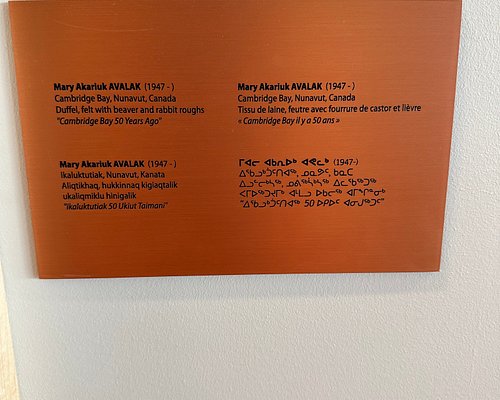

Visit museums and cultural centres, enjoy country food, and guided tours led by Indigenous-owned businesses and leaders. Enjoy Art? Browse soapstone sculptures at the Iqaluit gallery or Uqqurmiut Centre for Arts and Crafts in Pangnirtung. Or celebrate Inuit traditions at the Alianait Festival held in June or the Toonik Tyme Festival held every spring in Iqaluit, the capital.

Catch an Arctic Char

Commonly found in the freshwaters of Nunavut, Arctic Char are emblematic of the territory. So much so, that the name of towns reflect the importance of the salmonid. Abundant and readily accessible, if you’re eager to catch a Char , Nunavut is your place. The best time to catch Arctic Char is during summer from June to October. In the capital, Char can be found in Sylvia Grinnell River. Further north, the community of Pond Inlet provides the opportunity to reel in the Arctic Char. However, Char can be caught in nearly every community in Nunavut.

See the Northern Lights

Is viewing the Northern Lights on your bucket list? The Northern Lights, also known as Aqsarniit, in Inuktitut, are the result of solar particles entering the earth’s atmosphere. Regardless of the science, Nunavut is a prime destination to see nature's light show. For optimal viewing, visit from fall to winter, when skies are free of clouds.

Picture a treeless, ice-encrusted wilderness lashed by unrelenting weather with a population density that makes Greenland seem claustrophobic. Add polar bears, narwhals, beluga whales and a scattered Inuit population who have successfully mastered a landscape so harsh that foreigners could not colonize it.

Leave the planning to a local expert

Experience the real Nunavut. Let a local expert handle the planning for you.

Attractions

Must-see attractions.

Quttinirpaaq National Park

The northernmost and most mountainous of Nunavut's national parks, 37,775-sq-km Quttinirpaaq is Canada's second-largest, way up on Ellesmere Island. Now…

Kenojuak Cultural Centre & Print Shop

Though many Inuit communities now generate world-class artworks, Cape Dorset's remain the most revered. The new Kenojuak Cultural Centre, named after…

Uqqurmiut Centre for Arts & Crafts

Pang is famous for its lithographs, prints and tapestries, and this extraordinary place brings it all together. There are few tapestry studios in the…

Auyuittuq National Park

Among the globe's most flabbergasting places, Auyuittuq (ah-you-ee-tuk) means 'the land that never melts.' Appropriately, there are plenty of glaciers in…

Katannilik Territorial Park

Near Iqaluit and one of Nunavut's finest parks, Katannilik means 'Place of Waterfalls' and comprises two main features. A Canadian Heritage waterway,…

Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum

This friendly little museum in an old Hudson's Bay Company building showcases an engaging permanent collection of traditional Inuit clothing, tools,…

Ovayok Territorial Park

Ovayok Territorial Park, accessible via a rough road or 15km hike, is a prime place to see musk ox and offers good views from Mt Pelly (200m). It has some…

Matchbox Gallery

This small space is famed for having pioneered Inuit ceramic art. Watch artists at work, and browse and buy a wide range of beautiful handicrafts,…

Plan with a local

Experience the real Canada

Let a local expert craft your dream trip.

Latest stories from Nunavut

Filter by interest:

- All Interests

- Adventure Travel

- Art & Culture

- Beaches, Coasts & Islands

- Food & Drink

Feb 11, 2020 • 5 min read

After the winter darkness, Nunavut's capital, Iqaluit, celebrates the return of the sun with a raft of Inuit traditions.

Purchase our award-winning guidebooks

Get to the heart of Nunavut with one of our in-depth, award-winning guidebooks, covering maps, itineraries, and expert guidance.

Nunavut and beyond

- Get Paid to Review Campsites!

Stay in the Loop

Subscribe for exclusive content, giveaways, new products and more!

- Backpacking

- Backcountry Cooking

- Wilderness Medicine

- Destinations

- TRIP REPORTS

Arctic Travel , Nunavut

The ultimate nunavut travel guide.

Are you interested in experiencing the land of the midnight sun? A vast tundra of wildflowers, towering cliffs and meandering icebergs bobbing along freely in the arctic ocean? If this intrigues you, it sounds like you would be interested in travelling to Nunavut.

I spent four months living in Nunavut in 2015, made another visit in 2019 and I anticipate many more visits to come. In this post you’ll find everything you need to know to visit Nunavut yourself, as well as all the resources I’ve written about my favourite territory. Plus, throughout this post you’ll find external resources to provide even more information. If after all this, you have any additional questions, please leave a comment below!

This post may contain affiliate links. If you make a purchase through one of these links, I may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. Your support is much appreciated! You can learn more by reading my full disclosure .

Welcome to Nunavut

Nunavut is a destination as off-the-beaten-path as they come. Nunavut receives just 14,000 visitors each year; it is often forgotten by foreigners and Canadians alike. So if you aren’t familiar with Nunavut, you are not alone. Here are some quick facts and reasons why Nunavut is a great place to visit.

Quick Facts about Nunavut

Country : Canada

Demographic : Approximately 85% of the population is Indigenous, ~12% is Caucasian and the remaining ~3 % are visible minorities.

Language : Four official languages (English, Inuktitut, French and Inuinnaqtun)

Size : 2 million square kilometers (20% of Canada’s landmass)

Regions : Nunavut is divided into three regions:

- Qikiqtaluuk (Baffin) Region includes Baffin Island, Ellesmere Island and surrounding islands on the eastern and northern parts of Nunavut

- Kivalliq Region extends north from Manitoba and includes most of the land along the coast of Hudson Bay

- Kitikmeot Region is the land around the center and western border of Nunavut

Communities : Iqaluit is the capital city of Nunavut; it is the largest community with approximately 7,500 people. There are 25 other communities, with populations ranging from 100 to 2,500. None of the communities have road access between them, nor are they connected to southern Canada.

Read more : Interesting Facts About Nunavut

Reasons to Visit Nunavut

You visit Nunavut to experience life at the top of the world. Witness magnificent wildlife – polar bears, narwhals, beluga, caribou – in their natural environment. Watch lonely icebergs floating in the frigid arctic ocean. Catch the northern lights as they dance across the sky. Learn about Inuit traditions and modern ways of life. There is so much to do and experience in this territory.

Read more: The Honest Reason Why No On Visits Nunavut

Logistics of Traveling to Nunavut

Planning a trip to somewhere so off-the-beaten-path can be daunting. Here are the answers to the most common questions you may have about planning a trip to Nunavut.

What is the best time of year to visit Nunavut?

The best time of year to visit Nunavut depends a bit on the activities you are interested in doing. If you want to go snowmobiling on the tundra or dogsledding on the frozen arctic ocean, mid-February to April is the best time to visit Nunavut. If you want to go hiking or kayaking, I’d recommend visiting in August or September .

However, if you are interested in doing an arctic safari or staying at a fly-in lodge, hiking the Pang Pass or seeing particular wildlife, the best time to visit is a little different. I have a comprehensive post coming out soon on this topic.

Read more : The Best Time of Year to Visit Nunavut

How long should you spend in Nunavut?

Forever! Kidding, kidding (though after visiting you might want to). How long you spend in Nunavut will depend on whether you are doing a guided tour or visiting on your own.

Many guided tours are seven to ten days in length, though they can be much longer too. Regardless of the duration, you’ll want to arrive at your tour’s meeting place one or two days early, and depart one or two days after your tour ends.

Weather can be unpredictable in the arctic, and sometimes flights don’t get out exactly when planned.

If you’re visiting one of the communities on your own, you generally need less time. For example, I recommend people spend three to four nights in Iqaluit (you can read more about visiting Iqaluit below).

How do you get to Nunavut?

Getting to Nunavut is actually quite straightforward. You can fly to Iqaluit from Ottawa or Montreal, or to some of the larger communities from Yellowknife.

There are several small airlines operating in the north, with the two major airlines being First Air and Canadian North , both of which offer flights from the south. I recommend using Google Flights to see what airlines fly to the exact destination you are looking to travel to.

Read more : How to get to Nunavut, Canada’s Seemingly Inaccessible Territory

Things to do in Nunavut

There are plenty of activities to do in Nunavut, though they differ depending on whether or not you are going on your own or with a tour operator.

With a tour operator, you could visit a fly-in lodge or join a floe edge arctic safari for great wildlife viewing. There are tour operators in Nunavut who offer heli-skiing, cruises, dive trips and more. Going with a tour operator will be pricey, but can be an incredible experience. If you have the means, I highly recommend joining an arctic safari.

If you visit one of the communities in Nunavut on your own, here are some activities you could do (though it will vary by community). You could go snowmobiling or dogsledding in the winter, kayaking and hiking in the summer, visit cultural centres and attend a festival . You cansee the northern lights or check out Inuit art . There are lots of things to do in Nunavut!

Alternatively, Nunavut has four national parks you could plan a trip to. This would be on the pricier end and usually you need to have some experience camping in a remote area (or, of course join a tour operator).

Read more : Snowmobiling, Kayaking & More: 10 Incredible Things to Do in Nunavut

What are the best tour companies in Nunavut?

Note: I am not sponsored by any tour companies.

Arctic Kingdom

AK is the best tour company for arctic safaris. On their trips, you stay at a base camp where the land or sea ice (depending on time of year) meets the open ocean. These areas are hotspots for all different kinds of wildlife (polar bear, narwhal and beluga, to name a few). AK is the company I worked for when I was living in Nunavut and I assisted with Glaciers & Polar Bear trip.

Quark Expeditions

Quark are the experts in Antarctic travel, however they’ve been gaining ground in the Arctic as well. Their trips tend to be on large cruise-like ships, which I’ve heard are very comfortable but the boat itself can be quite noisy. A Quark representative told me that if you want to see arctic wildlife, go with Arctic Kingdom not Quark (the loud boats will scare away the wildlife).

Inukpak Outfitting

Inukpak is your guide for short trips in and around Iqaluit. They offer half and full day snowmobiling, dogsledding, hiking and kayaking trips. Inukpak also has some short multi-day trips leaving from Iqaluit.

Weber Arctic

Weber Arctic offers two fly-in lodges in Nunavut. If you’re interested in seeing the caribou migration, I recommend choosing Weber Arctic. They also offer fat-biking and heli-skiing trips if you’re looking for something more active.

Black Feather

Black Feathers offers backpacking tours in Nunavut, specifically in Auyuittuq, Quttinirpaaq and Sirmilik national parks. In addition, they also do multi-day canoe trips on Nunavut rivers like the Hood and Coppermine.

There are numerous tour companies in addition to the ones I’ve listed above. The Destination Nunavut website lists tour companies for specific communities, plus additional resources to make travelling to Nunavut as smooth as possible.

Planning a Visit to Iqaluit, Nunavut

What if I don’t have a ton of money? Can I still visit Nunavut?

Because of how remote Nunavut is, going on a multi-day tour (like an arctic safari or fly-in lodge) is extremely expensive. Does this mean a lack of funds will prevent you from ever travelling to Nunavut? Heck no! Luckily, travellers can visit Iqaluit (the capital city of Nunavut) for a taste of the arctic without breaking their budget.

How do you get to Iqaluit?

As mentioned above, you can fly to Iqaluit from Ottawa or Montreal with Canadian North airlines. Flights will generally cost about $700 each way, In my post How to Visit Nunavut on the Cheap , I have some tips for getting cheap airfare to Iqaluit.

How long should you spend in Iqaluit?

I recommend travellers spend four nights in Iqaluit . Three nights would allow you to do all the major activities, however weather can be unpredictable in Iqaluit so I think it helps to have a one day buffer.

Read more : 21 Unique Things to do in Iqaluit, Nunavut + The Ultimate Iqaluit Travel Guide

Where to Stay in Iqaluit

Iqaluit has four hotels, of which I recommend Accommodations by the Sea or The Discovery. However, as restaurants are extremely expensive in Iqaluit, I suggest looking at Airbnbs where you’ll have access to a kitchen. This is also a great way to meet residents in Iqaluit and learn more about life there.

What are the food options in Iqaluit?

There are two main grocery stores in Iqaluit – Arctic Ventures and North Mart . I think Arctic Ventures is better for produce, whereas North Mart has a greater selection of non-grocery items (it’s sort of like a Walmart in the north).

There are also some good restaurants. The Frobisher Inn has the Frob Kitchen & Eatery , and The Discovery Lodge Hotel has The Granite Room . These two options would be a little more high-end. Yummy Shawarma is also really good.

My favourites include The Storehouse (for the pool tables, though the food is decent) and Black Heart Cafe which has great lattes and amazing breakfast sandwiches (they put a hashbrown IN the sandwich – it’s heavenly). There is also a new (to me) brewery called NuBrew Co . in Iqaluit that my friends speak highly of, though I’ve never been there myself.

What activities are there to do in Iqaluit?

Many of the activities listed in 10 Incredible Things to do in Nunavut can be done in Iqaluit. This includes snowmobiling, dogsledding, kayaking, hiking, ATV-ing and cultural activities. I’ve written posts dedicated to my favourite activities and linked them below. I recommend contacting Inukpak Outfitting , as they lead most of the tours in and around Iqaluit.

Over Arctic Ocean & Endless Tundra: Snowmobiling in Iqaluit : If you’re visiting between February and April, one activity I recommend is snowmobiling on the arctic ocean. Whether you’ve snowmobiled before or you’re brand new, you’ll have an unreal experience snowmobiling here.

Ruff Riding: Dogsledding in Iqaluit : Thinking of going dogsledding in Iqaluit? Read about my experience dogsledding and all the information you need to book this experience yourself.

Stories from Living in Nunavut

As I said, I lived in Nunavut for four months when I was working as a tour guide. I led groups to hike onto the tundra, kayak around icebergs and more. It was a crazy summer and I picked up a few stories from my time living there.

How a flaming wooden dog gave me a social life in the Arctic : The story of a lonely girl trying to make a home in the arctic, and how one unexpected night changed everything.

North of the Arctic Circle: A Look Inside a Remote Arctic Base Camp : Go behind the scenes and into the inner workings of a remote arctic basecamp. I had the pleasure of working at one for ten days and I wish I could have stayed there longer. You can stay at one as a guest on an arctic safari.

The reality of arctic tourism, as explained by the youngest explorer to the North Pole : In this post I interviewed Tessum Weber about the harsh realities of tourism in the arctic. Astonishingly expensive trips, contributions to climate change and keeping the territory a seldom-traveled destination are all topics Tessum answers with refreshing honesty.

Travelling to Nunavut: Additional Resources

There are two destination marketing websites in Nunavut: Destination Nunavut and Nunavut Tourism . Both websites provide information to help you plan and book your trip.

I hope this has been helpful. Should you have any other questions, please comment below.

Mikaela | Voyageur Tripper

Mikaela has been canoeing, hiking and camping for over ten years. She previously worked as a canoeing guide in Canada, and spent a season guiding hiking and kayaking tours in the high Arctic. Mikaela is a Wilderness First Responder and Whitewater Rescue Technician.

MY FAVOURITE GEAR

Fleece Sweater

Down Jacket

Hiking Boots

Hiking Shirt

Hiking Pants

15 thoughts on “ The Ultimate Nunavut Travel Guide ”

Stay in touch.

Join our community of outdoor adventurers - you'll find trip inspiration, gear discussions, route recommendations, new friends and more!

What a magical place this is!! Nunavut seems like a wonderful place to visit. Off the beaten path but with all the essentials. I love the sled dogs, too!

Yes, it’s a beautiful place for sure, Alexandra! The dogs sure are cute. Thanks for the comment!

This looks like such a peaceful destination! I would love to visit someday and try dog sledding. Kayaking looks beautiful as well! Thanks for the tips!

You’re welcome Jordan! Glad you liked it. Dog sledding was great because, well, dogs. But honestly I preferred snowmobiling! Either way, tons to do up north. Hope you can make the trip up!

Oh my God,what an incredible place ,I wish to visit Nunavut sometime .loved all your pics.thanks for inspiring

Thanks Madhu! I’m glad you liked it. Nunavut really is an incredible place.

How interesting to discover this destination with you Mikaela! I am in awe with the landscapes and all the activities you can do here! It looks so amazing! Impressive that you lived there for 4 months too 🙂

It was a crazy four months for sure, Ophelie. I’d love to do it again (though maybe not in the winter).

I was just talking to my boyfriend about how we should go travel through Nunavut today! Love this post and am definitely saving it for our trip!

Oh yay I’m so excited about that Bettina! I really hope you’re able to make the trip next year!

Nunavut looks like such a snowy and beautiful place! I would love to visit.

Thanks for commenting Francesca, it really is! I hope you’re able to visit!

How about visiting in December? The websites mentioned have lots of info but limited on dates. Some tour company sites do not work or respond.

Hi Elizabeth – check out this post for complete information: https://www.voyageurtripper.com/what-is-the-best-time-of-year-to-visit-nunavut/

But in general, I don’t think December would be the ideal month. There’s a lot of darkness and you can’t do many of the activities outlined in the guide.

We are two retired Australians travelling to Nunavut in March-April 2024. l have tried everywhere to see if we might require a permit in Nunavut. We are visiting Ilaquit, Rankin Inlet, Arctic Bay and Resolute. Also, it is confusing as to which settlements are “dry” and not allowing alcohol. Can you please give us any advice? Thank you very much! Wendy. February 2024.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Facebook Group

The top 10 attractions in Nunavut

Things to do

A trip to Nunavut is spent learning about the region's unique wilderness and wildlife, about the Inuit people and their Thule ancestors, and about the powerful relationship between the two.

Nunavut's Capital, Iqaluit External Link Title is at the center of the action. Located on Baffin Island, this is where most trips to the territory begin and end. Traditional Inuit culture can be seen everywhere, from the city's fantastic arts and crafts, to the many festivals it hosts, to the artists, musicians and filmmakers that live there. Iqaluit is also located close to three territorial parks, each home to unbelievable scenery, beautiful natural features, and many archeological artifacts dating back to the ancient Thule people. Outdoor activities like skiing, snowmobiling and dogsledding are popular parts of daily life, as are hunting, fishing and berry picking. Stay in town to dine and explore, or head out into nature. Everything starts here.

Naujaat (Repulse Bay)

Naujaat External Link Title is a birdwatcher's paradise. The name even means "nesting place for seagulls" in the local Inuktitut language. Formerly known as Repulse Bay, this hamlet sits near a cliff area where seagulls are born every June. It's also located directly on the Arctic Circle, a fact marked by an impressive stone cairn found in the community. Only about 1,050 people live in Naujaat, meaning they're greatly outnumbered by the birds and other local wildlife. Rolling hills, beautiful inlets, and Arctic tundra form a landscape that tends to experience some pretty cold weather. But that shouldn't stop you from visiting in the warmer months, for great fishing, hunting ATV riding, hiking, kayaking, and, of course, birdwatching. From the seagulls, that gave it its name, to tundra swans, peregrine falcons, and snow geese, there are birds aplenty.

Auyuittuq National Park

Glaciers, rugged mountains and rivers dominate the terrain of Auyuittuq National Park External Link Title . The prospect of some challenging terrain attracts leagues of hikers and skiers, most of whom follow the 60-mile Akshayuk Pass (known locally as Pang Pass), a traditional Inuit travel corridor that crosses the park. We can't all take on 60 miles though, so visitors can also do day hikes to the Arctic Circle, or tackle the terrain via dogsled or snowmobile. If you're going to visit anything in the park, make it Mount Thor. The aptly-named mountain has the world's highest vertical drop, at 4,101 feet. It's really something to behold.

Sirmilik National Park

Sirmilik National Park External Link Title , on the northwest side of Baffin Island, has one of the most diverse sets of wildlife in the Arctic. Narwhals, caribou, polar bears, ringed seals, killer whales all travel the shore and the water beyond it. The park also houses an important bird sanctuary, Bylot Island, with over 70 species and hundreds of thousands of birds either nesting there, or passing through. At over 8,500 square miles, it stands to reason that wildlife would inhabit the park. But all that space also means lots of rooms for activities (beyond the obvious wildlife viewing). This includes mountain climbing, ski touring, sea kayaking, touring the floe edge and visiting archeological sites.

West Baffin Eskimo Co-Operative Limited

Carvings, etchings and stonecut prints are the bread and butter of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-Operative Limited External Link Title , a collection of Inuit artists based in Cape Dorset. The co-operative has existed for more than 50 years, and has since become arguably the Inuit art capital of the world. On the shores of the Hudson Strait, these artists ply their trade to the delight of the many art lovers that make the trip to the island year-after-year.

Cunningham Inlet (Somerset Island)

Plain and simple, Cunningham Inlet on Somerset Island is the best place in the world to watch beluga whales. Thousands of these beautiful animals visit the inlet every year to play, nurse their young and molt their skin. The consistency with which they visit and the remoteness of the site -- 500 miles north of the arctic circle -- make this a truly wild experience. Guests can shack up at the beautiful Arctic Watch Lodge External Link Title , and walk less than a mile for unrivaled views of these beluga pods, and enjoy all the other wildlife, natural beauty and archeological sites that fill Somerset Island.

Ellesmere Island

Nunavut is home to more than one big island. Ellesmere Island is second in size only to Baffin Island, and sits about as far north as Canada goes. It was from this island in 1909 that an explorer set out to walk to the North Pole, which is located only 447 miles away. In other words, Ellesmere Island is not a place to go sunbathing. It is a place to observe muskox, caribou, wolves and lemmings. It's also a great place to take canoe and snowmobile tours through great hunting land. And it's also an awesome place to test your gumption with mountain climbing, backpacking or, if you really want the memory of a lifetime, a North Pole excursion of your own. Did I mention the 24-hour daylight?

If you're going to visit the scenic hamlet of Pond Inlet External Link Title for one reason, and one reason only, make it the narwhals. These unicorns of the sea famously pass through the inlet in large pods, creating a really incomparable wildlife viewing experience. Located near the floe edge, Pond Inlet is also a great place to see other wildlife in the spring. Immerse yourself in the local culture and history, from a local theater group to a variety of archeological digs. And if you love to get outside, the icebergs, glaciers, mountains and fjords that really characterize the entire territory of Nunavut are all close by. Make sure to explore some ice caves, or check out the hoodoos -- tall, thin rock formations.

Iqalugaarjuup Nunanga Territorial Park

It might not be easy to say Iqalugaarjuup Nunanga Territorial Park External Link Title , but it is easy to love it. Five miles from Rankin Inlet, this beautiful park features a chain of lakes, tundra, wetlands and all the varieties of animals that inhabit these ecosystems. Thanks to the varied terrain, many trails, and ancient Thule archeological sites it contains, the park is a popular destination for hiking. While you can visit the park in the winter, by ski or snowmobile, most choose to come in the summer when the birds are chirping and the purple mountain flowers are in bloom. Bring your binoculars and see if you can spot a peregrine falcon, or wade into the waters and catch yourself an Arctic char.

The Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage is actually a sea route that connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through the Arctic Ocean above Canada. The famous route passes around and above Baffin Island, with lots to see along the way. Cruise the passage External Link Title , skirting icebergs as you trace the steps of arctic explorers. Hop a zodiac ashore to abandoned whaling stations, Hudson's Bay Company outposts and ancient Thule campsites littered with artifacts. Grab your binoculars to hone in on walrus, narwhal, polar bears and sea birds. If you'd rather stick to land, there's also a Northwest Passage Trail External Link Title that sees you walk among the relics of the men who first explored this trail.

Get inspired

Other articles you might enjoy

Nunavut's World-Class Trophy Fishing and Hunting

The top fall destinations across Canada

Best camping in Canada – with a twist

Fascinating national historic sites in Canada

5 New Year’s resolutions to check off in Canada

One national park to visit in every province and territory

Top Canadian spring adventures

Guide to traveling Canada safely

Top RV road trips in Canada

Things to Do in Nunavut, Canada - Nunavut Attractions

Things to do in nunavut.

- 5.0 of 5 bubbles

- 4.0 of 5 bubbles & up

- Good for a Rainy Day

- Budget-friendly

- Good for Big Groups

- Adventurous

- Good for Kids

- Hidden Gems

- Good for Couples

- Good for Adrenaline Seekers

- Honeymoon spot

- Things to do ranked using Tripadvisor data including reviews, ratings, photos, and popularity.

1. Baffin Island

2. Unikkaarvik Visitor Centre

3. Arctic Coast Visitor Centre

4. Legislative Assembly of Nunavut

5. Sylvia Grinnell Territorial Park

6. Auyuittuq National Park

7. Apex Beach

8. Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum

9. St. Jude's Cathedral

10. Ellesmere Island

11. Sirmilik National Park

12. The Matchbox Gallery

13. katannilik territorial park.

14. Margaret Aniksak Visitor's Centre

15. Northern Collectables

16. Qaummaarviit Territorial Park

17. angmarlik visitor centre.

18. Nunavut Brewing Company

20. Iqalugaarjuup Nunanga Territorial Park

21. Carvings Nunavut

22. Ovayok Territorial Park

23. Kugluktuk Visitor Heritage Centre

24. Tasiluliariaq Rotary Park

25. soper river (kuujjuaq).

26. Canadian High Arctic Research Station

27. Inukpak Outfitting

28. Quttinirpaaq National Park

29. Apex Trail

30. Kivalliq Regional Visitor Centre

What travelers are saying.

- Unikkaarvik Visitor Centre

- Baffin Island

- Quttinirpaaq National Park

- Ellesmere Island

- Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum

- Sylvia Grinnell Territorial Park

- Auyuittuq National Park

- Sirmilik National Park

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Kikkert, Peter. "Nunavut". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 31 January 2023, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/nunavut. Accessed 27 April 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 31 January 2023, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/nunavut. Accessed 27 April 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Kikkert, P. (2023). Nunavut. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/nunavut

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/nunavut" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Kikkert, Peter. "Nunavut." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published August 09, 2007; Last Edited January 31, 2023.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published August 09, 2007; Last Edited January 31, 2023." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Nunavut," by Peter Kikkert, Accessed April 27, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/nunavut

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Nunavut," by Peter Kikkert, Accessed April 27, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/nunavut" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Article by Peter Kikkert

Published Online August 9, 2007

Last Edited January 31, 2023

Nunavut, or “Our Land” in Inuktitut, encompasses over 2 million km 2 and has a population of 36,858 residents (2021 census), 30,865 of whom are Inuit. Covering roughly the part of the Canadian mainland and Arctic Archipelago that lies to the north and northeast of the treeline, Nunavut is the largest and northernmost territory of Canada and the fifth largest administrative division in the world. Nunavummiut live in 25 communities spread across this vast territory, with the largest number, 7,429 (2021 census), in the capital, Iqaluit. The creation of Nunavut in 1999 (the region was previously part of the Northwest Territories) represented the first major change to the political map of Canada since the incorporation of Newfoundland into Confederation in 1949. Beyond changing the internal political boundaries of Canada, Nunavut’s formation represented a moment of great political significance; through political activism and long-term negotiations, a small, marginalized Indigenous group overcame many obstacles to peacefully establish a government that they controlled within the Canadian state, thereby gaining control of their land, their resources and their future. As such, the creation of Nunavut represents a landmark moment in the evolution of Canada and a significant development in the history of the world’s Indigenous peoples.

Nunavut covers 1,936,113 km 2 of land and 157,077 km 2 of water in Northern Canada, representing 21 percent of the country’s total area. The territory includes part of the mainland, most of the Arctic Archipelago , and all of the islands in Hudson Bay , James Bay and Ungava Bay . Nunavut is divided by three of Canada’s seven physiographic regions . These regions are the Hudson Bay Lowlands , the Canadian Shield and the Arctic Lands .

The Hudson Bay Lowlands are a sedimentary basin in the middle of the Canadian Shield . The Canadian Shield comprises much of the mainland, certain islands around Hudson Bay and parts of the Arctic Archipelago . The lowlands of the Canadian Shield rest on a bed of rock that is at least 1 billion years old. They are covered by a thin layer of soil, and are often poorly drained and flat. A defining characteristic of this physiographic region are the thousands of lakes and rivers that dot the surface.

The Arctic Lands physiographic region extends throughout the northern half of Nunavut . It includes most of Canada’s Arctic Archipelago . The eastern edge of the Archipelago is a mountainous zone, with elevations approaching 2,000 m in the north, and a heavily fjorded coast. In sharp contrast, the central and western islands are relatively flat, with low relief. On the northern islands, night lasts for 24 hours during the winter months, while day lasts for 24 hours during the summer.

Much of the land in Nunavut is characterized as tundra , which is bare, rocky and treeless. The soil of the tundra is locked in permafrost . The Arctic is experiencing climate warming faster and more intensely than most other parts of the world. Changes in Nunavut include higher temperatures, melting permafrost, reduced sea ice, thinning and retreating glaciers and diminished ice shelves. These changes threaten polar bears , seals , walruses , caribou and many other species on which traditional Inuit harvesting practices depend. ( See also Geography of Nunavut .)

Pre-Dorset and Dorset Culture

During the last Ice Age , much of Nunavut was covered by a thick sheet of glacial ice. Between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago the glaciers covering Nunavut melted, and shortly afterward the landscape filled with caribou and muskoxen , while walrus , seals and whales moved into the channels between the islands. While Indigenous peoples followed migrating caribou to the edge of the treeline on the mainland, they never ventured to the Arctic coastline or the islands beyond.

Around 5,000 years ago, however, the first people began to explore the lands and sea that now make up Nunavut. In a wave of migration that likely started in Siberia, the Palaeo-Inuit of the Pre-Dorset culture moved in small groups across the Arctic coastline and Archipelago, pushing through to Greenland and Labrador . As they encountered the different ecosystems and geography of the Arctic, they adapted their hunting techniques and tool technology. In Nunavut, they hunted muskoxen and caribou with bow and arrow, and seals, fish, walruses and even small whales by throwing harpoons from the shore or sea ice. For shelter, they crafted tents out of animal skin. The small cutting edges of their stone tools have led archaeologists to call the Pre-Dorset culture the Arctic Small Tool Tradition.

The Pre-Dorset way of life transitioned to the Dorset culture 2,500 years ago, characterized by markedly different tool technology, including triangular blades and soapstone lamps. The Dorset hunted sea mammals, including narwhal and walrus. Unlike their predecessors, the Dorset lived in more permanent houses made of snow, stone and turf.

About 1,000 years ago, another wave of migration started to move from the southern Bering Sea to the eastern Arctic. These people, known as the Thule , adapted a maritime hunting culture with the tools, boats and skills required to harvest the larger whales found in the waters of the Arctic Archipelago . Advanced tool technology that included the sealskin kayak, the open skin boat known as the umiaq, harpoons, fishing spears, lances, bows and arrows, a type of knife called the ulu, soapstone lamps and pots, and snow goggles, helped the Thule to successfully travel on the land and effectively harvest the animals that sustained them. In addition to whales, the Thule also harvested seal, fish, caribou and smaller mammals. The large volumes of food provided by the seal hunts allowed the Thule to live in larger, more permanent communities, often a dozen or more houses made of stone slabs, sod and whalebone. In these villages, people had ample leisure time to craft their sophisticated tools, often out of metal, and develop their vibrant culture, expressed in elaborate carvings, amongst other crafts.

As the Thule pushed into the Arctic Archipelago, they moved into land inhabited by the Dorset. Inuit oral tradition remembers the Dorset as the Tuniit or the Sivullirmiut (the first inhabitants) and describes these people as peaceful giants, taller and stronger than the Thule. While there may have been some intermarriage or conflict between the two groups, on the whole a pattern of encounter and retreat seems to have been followed, with the Dorset choosing to keep their distance from the Thule and their culture. As the Dorset retreated into more marginal and inhospitable zones, the struggle to survive became ever more difficult. Although the idea is disputed between archaeologists, there is a chance that a small group of Dorset people known as the Sadlermiut survived in a small, isolated community on Coats , Walrus and Southampton islands in Hudson Bay (near the present-day Nunavut community of Coral Harbour ) until they died of an epidemic in the early 20th century.

Around 500 years ago, Thule culture changed dramatically. In response to a cooling climate, the Thule abandoned most of the northern Archipelago. In addition, their permanent villages started to break apart as the people embraced a more migratory life based on seasonal subsistence patterns shaped by local environments. The people now lived in small shifting family groups with a non-hierarchical social organization.

The shift in Thule culture ended in the emergence of the diverse Inuit societies that exist in Nunavut today. Throughout the Kitikmeot, groups of Inuit — the Inuinnait and the Netsilingmiut — thrived in a pattern of life perfectly adapted to the environmental conditions of the central Arctic. In a seasonal cycle that repeated year after year, they lived in large iglu villages on the sea ice and hunted seals during the winter months before returning to the land in smaller groups to fish and hunt caribou in the spring and summer. These groups were amongst the most nomadic people in the North American Arctic, and they travelled extensively in their seasonal cycle as they sought the best hunting and fishing grounds in the region.

In the coastal areas of the Kivalliq, the Kivallirmiut (also called Caribou Inuit) adapted to life in the interior, where they hunted caribou and geese and fished for trout . Their dependence on inland rather than coastal resources made them unique among Inuit societies. During the fall hunt, populations gathered at a few good hunting spots to replenish their food supplies for winter. Caribou skins were used to make clothes and containers, as well as tents during the summer months and snowhouses during the winter.

In the Qikiqtaaluk, the different groups of Baffin Island Inuit and the Iglulingmuit adapted to their local environments. The people of the Qikiqtaaluk harvested walruses , seals , caribou and arctic char.

Throughout Nunavut, Inuit developed rich and vibrant cultures and traditional knowledge systems strongly connected to their local environments. At the same time, they also participated in extensive trade networks, exchanging skins, driftwood, soapstone, flint, copper, clothing and tools. ( See also Indigenous People: Arctic .)

European Exploration

The first Europeans to explore parts of Arctic North America were the Norse. After settling along the southwestern coast of Greenland after the year 980, groups of Norse intermittently ventured to the eastern fringe of the Arctic Archipelago until about 1450 CE in search of resources and trading partners. Most scholars agree that the Norse called Baffin Island “Helluland.” Archaeological remains indicate that as the Norse ventured into the region, they met and traded with first the Dorset and then the Thule inhabitants.

In the first European forays into the Arctic Archipelago in the 16th and early 17th centuries, explorers searched for a commercial route to Asia, a water passageway known as the Northwest Passage linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans above northern North America. During three expeditions in the late 1570s, Martin Frobisher explored Greenland (the Norse abandoned the area in the early 15 th century), sailed into the bay on southeastern Baffin Island that now bears his name and claimed the region for Queen Elizabeth I. By 1620, John Davis , Robert Bylot and William Baffin had followed Frobisher’s route and pushed further north into Davis Strait , Smith, Jones and Lancaster Sounds and charted the eastern coastline of Baffin Island. Soon after, English efforts relocated to the southerly reaches of the North American archipelago, where in 1610 Henry Hudson explored the enormous bay named after him. By the end of the century, the newly formed Hudson’s Bay Company dominated exploration in the North, but its focus on the subarctic fur trade left little incentive to support forays into the Arctic Archipelago. With a great deal of assistance from Indigenous peoples and their technologies, Samuel Hearne made it to the Arctic coast by way of the Coppermine River in 1771, stopping at what is now Kugluktuk .

After French leader Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo in 1815, the British Royal Navy “ruled the waves.” Without a war to fight and Britain’s sea-lanes of trade and communication secure, the navy struggled to find an outlet for its energies. Government-sponsored polar exploration provided a purpose for the Royal Navy and a testing ground for its ships and men, while adding to British power and prestige. Between 1818 and 1845, the navy uncovered large parts of Arctic North America as it sent its ships and crews into the ice and labyrinth of islands in the Archipelago ( see Arctic Exploration ).

By the 1840s, seaborne expeditions led by John Ross and William Parry had explored parts of the eastern and central Archipelago, while overland expeditions by Hudson’s Bay Company explorers had illuminated more of the western end of the Northwest Passage. As a result, the British government felt confident that a new expedition led by 59-year-old John Franklin would finally conquer the Passage. His two ships, Erebus and Terror , were the first to sail through Peel Sound but became trapped in the ice near King William Island (with the assistance of Inuit oral history, the Erebus was found in 2014, the Terror in 2016). Franklin died in June 1847, and the remaining crews abandoned the ships the following spring of 1848 in a fatal attempt to walk to the closest settlement, hundreds of kilometres to the south. Everyone succumbed to starvation and exhaustion. Subsequent British searches to determine what happened to the expedition, which seemed to vanish without a trace, crisscrossed the centre of the Arctic Archipelago by ship and sledge, filling in a large part of the map and uncovering three Northwest Passages. ( See also Exhibit: Arctic Exploration ).

The Franklin search internationalized exploration in the Arctic Archipelago. Englishman E.A. Inglefield and Americans E.K. Kane, I. Hayes and C.F. Hall navigated the channel between Greenland and Ellesmere Island , and the survey of Ellesmere’s east shore was completed by the 1875–76 British polar expedition under G.S. Nares. In 1876, P. Aldrich rounded the top of Ellesmere Island and named the northernmost point of what is now Canadian territory Cape Columbia. Norwegian Otto Sverdrup explored the western shore of Ellesmere Island (1898–1902). Sverdrup and his men also surveyed the entire coast of Axel Heiberg Island , and to the west discovered and mapped Amund Ringnes and Ellef Ringnes islands and King Christian Island. From 1903 to 1906, another Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen , made use of the internal combustion engine to propel his 47-ton Gjøa through the Northwest Passage for the first time.

Between 1913 and 1918, the northern party of the Canadian Arctic Expedition (CAE), led by Vilhjalmur Stefansson , outlined the edge of Canada’s continental shelf and discovered some of the world’s last major land masses — Lougheed, Borden , Mackenzie King , Meighen and Brock islands — while drifting dangerously but deliberately on ice floes. Meanwhile, the southern party explored much of the Kitikmeot region, contacting groups of Inuinnait and extensively studying their culture and language.

Over this time, many groups of Inuit encountered European explorers and started to trade furs and other traditional items for European food and metal tools. Inuit played important roles in many of these expeditions, as hunters, guides and interpreters, even assisting the Europeans with their mapmaking. Many explorers owed their success — and lives — to Inuit who taught them how to travel effectively, dress properly for the weather and live off the land.

Whalers, Fur Traders and Missionaries

While the explorers initiated contact with many Inuit groups, the arrival of whalers, fur traders and missionaries had a far greater impact. In the late 18th century, European whaling operations began in the Eastern Arctic, and by 1840, American, English and Scottish whalers had established year-round shore stations in Cumberland Sound, where they occasionally hired Inuit families to work for them. This long-term European presence brought greater trade to the Inuit groups in the region, but also more diseases. Extensive whaling operations also led to overharvesting, which led whaling crews to expand their focus to caribou and muskox , depleting many of animals essential to Inuit subsistence patterns. By the end of the century, the whaling industry in the Eastern Arctic had come to an end.

By the late 19th century, fur traders started to move into the territory that now makes up Nunavut. In the early 20th century, fur-trading posts were established at the sites of many of the communities that now exist in Nunavut. The involvement of Inuit in the fur-trade economy changed their lives in subtle ways. With a steady source of cash income now available, Inuit could purchase a steady stream of hunting supplies, canned food and luxury goods from the fur traders. These trade goods, which included new technologies such as rifles, stoves and steel traps, changed how they hunted and lived on the land. To attend to their trap lines between April and November, many Inuit in the central Arctic settled into coastal trapping locations rather than in winter sealing camps on the sea ice, ending the seasonal cycle that their ancestors had embraced for centuries. Focus on the fur trade shifted Inuit from focus on hunting solely for food, clothing and shelter to supplying outsiders with goods. This altered traditional trade and migration patterns, and some Inuit chose to settle closer to the fur-trading posts.

In the footsteps of the whalers and fur traders came the missionaries, both Catholic and Protestant, who established churches, provided health care and established mission schools — often in competition with one another. Many missionaries promoted practices and ideals that challenged the Inuit belief system and attempted to end certain traditional practices. In the eastern and western Arctic, missionaries translated the New Testament into Inuit dialects using a system of syllabic writing.

While these developments changed the way that Inuit lived and sometimes brought additional hardships, none were as serious as the epidemics that the Europeans brought with them. Measles, tuberculosis and influenza killed many Inuit.

Although life started to change with the influx of whalers, fur traders and missionaries, as well as with the introduction of a new economy, new religions and new technologies, many Inuit in Nunavut were able to maintain their traditional subsistence patterns well into the 20th century. Inuit continued to travel extensively, moving between their new trap lines and the best hunting and fishing areas. “We work hard then. We travelled much,” Elder Ekalun told Weekend Magazine in 1970. “If one was lucky, one had lots to eat. If one had no luck, one was hungry. Often one was hungry. But then came again good times. And the people were happy and danced.”

Canadian Government Administration

During much of the 19th century, the British government and its Colonial Office spent little time thinking about their claim to the islands. While explorers planted flags and made claims, Britain never formally annexed the Arctic Islands into its empire. In the 1870s, however, concerns arose about potential American claims to the islands of the Archipelago . In 1880, Britain transferred its rights to the islands to Canada. For its part, after 1880, Canada did little to consolidate its administrative or practical control over the Archipelago. By the turn of the century, the activities of foreign explorers in the High Arctic islands and ongoing concerns about the strength of its legal claims prompted the Canadian government to extend its efforts in Arctic North America. Joseph-Elzéar Bernier patrolled the waters of Hudson Bay and the Arctic islands, asserting control and indicating Canada’s supervision over the region. Bernier intercepted and imposed licenses on foreign whalers, collected customs duties, conducted geographical research and planted the flag on many northern islands.

In 1919 and 1920, concerns over the Danish government’s alleged denial of Canadian sovereignty over Ellesmere Island led to greater government activity on the eastern fringe of the archipelago. In 1922, the Liberal government of William Lyon Mackenzie King instituted an annual ship patrol in the Eastern Arctic and established new RCMP posts at Pond Inlet on Baffin Island and Craig Harbour on Ellesmere. When in 1925 an American expedition announced its plans to explore the area above Ellesmere Island and refused to ask the Canadian government’s permission, it led to more police posts and patrols around the islands of the Archipelago and Ottawa’s insistence that any explorer or scientist who wished to travel in the Archipelago must apply to Ottawa for a license. In 1930, negotiations with the Norwegian government led to its recognition of Canada’s sovereignty over the Sverdrup Islands .

As the Canadian government extended its administration throughout Nunavut, it also tried to determine its relationship with Inuit. Although the collapse of the fur trade in the 1930s led the federal government to initiate relief programs for certain groups of Inuit, in order to save administrative costs, official policy continued to promote a traditional, self-sufficient way of life for Inuit into the 1950s. In 1939, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in the Re Eskimo case that, constitutionally, Inuit should be classified as Indians in Canada, which made them the legal responsibility of the federal government. Still, no comprehensive Inuit policy emerged. In 1951, the government amended the Indian Act to exclude Inuit. As these events went on in Ottawa, most Inuit continued their traditional life, although contact with people from the South slowly increased.

Second World War

During the Second World War , the American military developed several ambitious defence projects for what is now Nunavut, including the Crimson Route, an alternate path for ferrying planes and material to Britain. Air bases were built, complete with support facilities and the required infrastructure. The Crimson Route involved installations at Churchill , Manitoba; Southampton Island in Hudson Bay ; Fort Chimo (Kuujjuaq); Iqaluit (then called Frobisher Bay by non-Inuit); Padloping Island in Davis Strait’s Merchants Bay; and other northern sites. The presence of large numbers of American military personnel at these installations had a large impact on Inuit living near them. During the war the Canadian government also started to issue identification disks to Inuit in order to keep track of them — reducing them to a number for administrative ease (this practice was only discontinued in 1971, when all Inuit selected surnames).

Did You Know? On 27 January 2020, Inuit elder Qapik Attagutsiak was recognized by Parks Canada as a “Hometown Hero” for her “significant” contributions to Canada’s Second World War effort. Qapik was part of a nationwide effort to recycle bones, fats, metals and rubber for wartime production. Living on an island near Igloolik , west of Baffin Island ( Nunavut ), Qapik collected walrus and seal bones which were used to make aircraft glue, fertilizer, and cordite (a type of explosive used in bullets). Qapik, 99, was honoured by Nunavut Commissioner Nellie Kusugak and Minister of Environment and Climate Change Jonathan Wilkinson at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau , Quebec.

As relations between the Soviet Union and the United States deteriorated after the Second World War , it became obvious to defence planners that the Arctic would form the front line if another world war broke out. In the years that followed, air bases and military stations were built across Nunavut, culminating in the construction of the Distant Early Warning Line — a radar line that could provide advanced warning of incoming Soviet bombers — in 1955. The construction of the DEW Line stations brought hundreds of ships, planes and workers to the Canadian Arctic. They brought with them buildings, steel towers, oil drums, electronic equipment, paint, wood, wire and all types of construction gear. This, and the other defence activities that the Cold War inspired, forever changed the face of Nunavut and the lives of Inuit.

Military construction became a key impetus for Inuit to settle in permanent communities. The military recruited Inuit to work on construction projects, which caused many to come off the land and settle around military installations. While many performed janitorial duties and manual labour, others received training as mechanics, carpenters, drivers and heavy equipment operators. Inuit workers continued to hunt and fish whenever they had a chance, but more families started to supplement country food with whatever rations they could secure from personnel working at the DEW Line stations. The wage economy began to undermine the traditional social organization of the Inuit, changed family life and parenting norms (as men left for weeks at a time) and altered gender roles. For many Inuit, the DEW Line brought a dramatic shift from a self-sustaining nomadic life to sedentary community life and a wage-based economy. New clothes, new housing and new technology all led to rapid lifestyle changes in a very short period of time.

The construction phase of the DEW Line lasted only a couple of years. While some Inuit workers found full-time work at the stations, more were laid off. The fur trade still offered some cash income, and many Inuit continued to work their trap lines. For most, however, the fur trade could not provide full-time employment. Some Inuit found work with the various government agencies that moved into the North, while others had to live off casual employment and social assistance. With few jobs available, unemployment persisted as a major problem in every community in the decades ahead.

Paternalism and the Welfare State

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Canadian government became even more involved in the everyday lives of Inuit as it sought to expand its administrative activities in the North. In so doing, Ottawa jettisoned the old policy of “keeping the Native Native” and became far more paternalistic in its approach, often causing great damage to Inuit. In the 1950s, Ottawa forcibly relocated Inuit from Inukjuak in Northern Québec to Grise Fjord and Resolute , ostensibly to provide them with better hunting grounds and greater prosperity, although many Inuit and historians argue that the government wanted to create a permanent human presence in the High Arctic to bolster Canada’s sovereignty over the region. During the construction of the DEW Line, the federal government started to post Northern Service Officers (NSO) to administer the new communities forming in Nunavut. In addition, the government initiated social welfare programs for housing, education, health care and economic development. In order to receive an education, however, many Inuit youth had to attend residential schools and federal hostels far from their communities, where they experienced emotional, physical and sexual abuse, as well as assimilatory practices that assaulted their language, culture and spiritual beliefs.

Housing remained the first and most pressing problem for the expanding communities. Adequate housing could neither keep up with the number of new people migrating into the communities, nor could casually employed and unemployed Inuit afford houses. Overcrowding became a major problem. After reports of the deplorable living conditions arrived in Ottawa, a government-administered housing program was started to send prefabricated houses to the communities in the early 1960s. As communities developed, traditional methods of subsistence proved increasingly difficult, given the lengthy travel times to available resources and the need to engage in the wage economy.

The Canadian government initiated its northern policies without consulting Inuit. Ottawa’s paternalistic approach was highlighted during the 1952 meeting of the Canadian Eskimo Affairs Committee, when a senior government official said, “The only reason why Eskimos were not invited to the meeting was…that it was felt that few, if any, of them have yet reached the stage where they could take a responsible part in such discussion.” A territorial council in Ottawa administered the whole of the Northwest Territories , which then stretched over one third of Canada’s land mass. Slowly, however, Inuit became more politically active. Inuit became involved in local government and administrative organizations such as town and hamlet councils and housing authorities. In 1950, Inuit became eligible to vote in federal elections, and in 1966 the first Inuk, Simonie Michael, was elected to the NWT Council. Additional changes came in 1967 when the territorial government moved from Ottawa to Yellowknife , but even this was incredibly distant for Inuit living in the Eastern Arctic.

The Creation of Nunavut

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Inuit across the Canadian Arctic started to organize to discuss land claims and better governance options. In 1971, the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada was formed and was heavily involved in the preparation of the first Inuit land claims proposal in 1976. This proposal called for a land claim and the creation of a new territory, administered by a new government. In this territory, Inuit would have political control through their sheer numbers and voting power. The proposal was soon withdrawn, however, because of its complexity, lack of community input and concern that it had been overly influenced by southern consultants. First the NWT Inuit Land Claims Commission (1977), then the Nunavut Land Claims Project (1979) and finally the Tunngavik Federation of Nunavut (1982) were formed to deal with the land claims negotiations. In these negotiations, Inuit consistently clashed with the federal government over whether the land claims should include the political division of the Northwest Territories , leading to the creation of a new territory. Only after years of debate was the idea of Nunavut accepted by the federal government, but it was still decided to negotiate the creation of the new territory separate from the land claim.

The concept of a separate Nunavut steadily grew. In 1979, the Northwest Territories was divided into two federal electoral districts, with the new eastern district of Nunatsiaq corresponding to what would become Nunavut. The first member elected in that district, Peter Ittinuar , was also the first Inuk to sit in the House of Commons . In 1982, the NWT Division Plebiscite ended with 56 percent of the voters in favour of division. In the eastern Arctic, where the Inuit population was highest, the percentage in favour of division reached 80 percent. Afterwards, the Nunavut Constitutional Forum was created to plan for the division. While there was much debate over the boundary line between Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, in 1992 the proposed boundary passed in another plebiscite.

An agreement-in-principle on the land-claims settlement was finally reached in 1990. Members of both the Tunngavik Federation and federal negotiating teams signed this document, the “Nunavut Land Claims Agreement” (NLCA), in September of 1992. It was then put to a plebiscite in October of 1992 and saw a record turnout of voters, who passed the agreement with an overwhelming majority of 84.7 percent. The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act — the largest Indigenous land-claims settlement in Canadian history — which ratified the agreement, and the Nunavut Act , which created the new territory, were both passed on 10 June 1993 (the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act came into force on 9 July 1993). The NLCA granted Inuit the right to hunt, fish and trap throughout the territory. That Agreement subdivided Nunavut into three designations of land: 1) Crown lands over which Inuit have the right to hunt, trap, fish and participate in management; 2) 318,084 km 2 of Inuit-owned land, including rights to the ground’s surface but not what lies beneath; and 3) 37,883 km 2 of Inuit-owned land including both surface and subsurface rights. Inuit were invited to select the parcels of land for each designation. In compensation for the Crown lands that were not to be Inuit property, the federal government agreed to pay recognized Inuit organizations $1.17 billion over 14 years.

After ratification of the two acts in 1993, attention turned toward implementation. This process was led by Chief Commissioner John Amagoalik, while the land-claims settlement process was spearheaded by Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI). Over the next few years, these groups created new government departments and trained employees. On 15 February 1999, the first election was held in Nunavut to vote in the first members of the legislative assembly. After the election, the assembly chose Paul Okalik as the territory’s first premier, while the federal government appointed Helen Maksagak as the first Commissioner of Nunavut. On 1 April 1999, Nunavut officially separated from the Northwest Territories to become the newest Canadian territory.

Did You Know? Nunavut Day is celebrated annually on July 9 , even though Nunavut officially became a territory of Canada on April 1 , 1999. The date of July 9 was chosen because it commemorates the passing of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act (1993), a milestone agreement between the people of Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, and the federal government of Canada, paving the way for the establishment of Nunavut in 1999.

Demographics

Until 2016, Nunavut was the least inhabited province or territory in Canada, a title it has since lost to Yukon. As of 2016, the territory has the strongest population growth in the country, reporting a 12.7 percent increase between the 2011 and 2016 censuses (the population rose from 31,906 to 35,944). Most of this population increase is the result of Nunavut possessing the highest fertility rate in Canada — an average of 2.9 children per women, well past the national average of 1.5. This rapid growth has earned Nunavut another important distinction: it has the youngest population in Canada, with about 30 percent of Nunavummiut being under the age of 14 in 2016.

Language and Ethnicity

There are four official languages spoken in Nunavut — Inuktitut , Inuinnaqtun (a dialect of Inuktitut spoken in Kitikmeot), English and French. Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun is the mother tongue of 65.1 percent of Nunavummiut. While English is spoken throughout the territory, Iqaluit is also home to a large francophone community. Nunavut has the only act (the Inuit Language Protection Act ) in Canada that aims to protect and revitalize an Indigenous peoples’ language and insists that the Government of Nunavut take positive action to advance the Inuit language in government, education and other public services.

According to the 2021 census, 30,865 residents of Nunavut are Inuit. Following Inuit, the two most commonly cited ethnicities were Scottish and Irish, accounting for 9.2 and 4.9 percent of the population respectively.

In 2001, the last year statistics are available, over 93 percent of Nunavummiut identified as Christian.

Communities

List of Nunavut’s 10 Largest Communities

Source: Statistics Canada, 2021 Census

Nunavut’s population of 36,858 residents is spread out across 25 communities, ranging in size from a couple of hundred people to 7,429 in Iqaluit , the territory’s capital. Most of these communities are geographically isolated and accessible only by air and sea.