PODCAST: HISTORY UNPLUGGED J. Edgar Hoover’s 50-Year Career of Blackmail, Entrapment, and Taking Down Communist Spies

The Encyclopedia: One Book’s Quest to Hold the Sum of All Knowledge PODCAST: HISTORY UNPLUGGED

Reasons for Westward Expansion

What were the reasons for Westward expansion? Ever since the first pioneers settled in the United States at the East , the country has been expanding westward. When President Thomas Jefferson bought the Louisiana territory from the French government in 1803, it doubled the size of the existing United States. Jefferson believed that, for the republic to survive, westward expansion was necessary to create independent, virtuous citizens as owners of small farms. He wrote that those who “labor the earth” are God’s chosen people and greatly encouraged westward expansion. The pioneers who flocked to the West, all had their own set of reasons for taking on the long, treacherous journey to settle there.

Reasons for Moving West

- There was a vast amount of land that could be obtained cheaply

- Great reports were continually sent back East about how fruitful and wonderful the West is, sparking a lot of interest.

- The constraints of European civilization had a lot of people stuck in factory and other low-paid jobs. For the working class it was almost impossible to work themselves up in life, something that was very doable in the New World.

- Mining opportunities, silver, and the gold rush was a big draw for many

- The expanding railroad provided easier access to supplies, making life in the West easier.

- Certain wheat strains were discovered and was capable of adapting to the climate of the plains

- Being a “cowboy” and working on farms with cattle was romanticized

- The lure of adventure

This article is part of our extensive collection of articles on the American West and Native Americans. Click here to see our comprehensive article on the American West and Native Americans.

Additional Resources About American West and Native Americans

American west timeline, native american tribes and nations: a history, the cattle industry in the american west, native american people – origins, cite this article.

- How Much Can One Individual Alter History? More and Less...

- Why Did Hitler Hate Jews? We Have Some Answers

- Reasons Against Dropping the Atomic Bomb

- Is Russia Communist Today? Find Out Here!

- Phonetic Alphabet: How Soldiers Communicated

- How Many Americans Died in WW2? Here Is A Breakdown

4 Routes to the West Used by American Settlers

Roads, Canals, and Trails Led the Way for Western Settlers

Artodidact / Pixabay

- America Moves Westward

- Important Historical Figures

- U.S. Presidents

- Native American History

- American Revolution

- The Gilded Age

- Crimes & Disasters

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/McNamara-headshot-history1800s-5b7422c046e0fb00504dcf97.jpg)

Americans who heeded the call to "go west, young man" may have been proceeding with a great sense of adventure. But in most cases, those trekking to the wide-open spaces were following paths that had already been marked. In some notable cases, the way westward was a road or canal which had been constructed specifically to accommodate settlers.

Before 1800, the mountains to the west of the Atlantic seaboard created a natural obstacle to the interior of the North American continent. And, of course, few people even knew what lands existed beyond those mountains. The Lewis and Clark Expedition in the first decade of the 19th century cleared up some of that confusion. But the enormity of the west was still largely a mystery.

In the early decades of the 1800s, that all began to change as very well-traveled routes were followed by many thousands of settlers.

The Wilderness Road

George Caleb Bingham / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

The Wilderness Road was a path westward to Kentucky established by Daniel Boone and followed by thousands of settlers in the late 1700s and early 1800s. At its beginning, in the early 1770s, it was a road in name only.

Boone and the frontiersmen he supervised managed to link together a route comprising old Indigenous peoples' pathways and trails used for centuries by herds of buffalo. Over time, it was improved and widened to accommodate the wagons and travelers.

The Wilderness Road passed through the Cumberland Gap , a natural opening in the Appalachian mountain range, and became one of the main routes westward. It was in operation decades before other routes to the frontier, such as the National Road and the Erie Canal.

Though Daniel Boone's name has always been associated with the Wilderness Road, he was actually acting in the employ of a land speculator, Judge Richard Henderson. Recognizing the value of vast tracts of land in Kentucky, Henderson had formed the Transylvania Company. The purpose of the business enterprise was to settle thousands of emigrants from the East Coast to the fertile farmlands of Kentucky.

Henderson faced several obstacles, including the aggressive hostility of the Indigenous tribes who were becoming increasingly suspicious of white encroachment on their traditional hunting lands.

And a nagging problem was the shaky legal foundation of the entire endeavor. Legal problems with land ownership thwarted even Daniel Boone, who became embittered and left Kentucky by the end of the 1700s. But his work on the Wilderness Road in the 1770s stands as a remarkable achievement that made westward expansion of the United States possible.

The National Road

Doug Kerr from Albany, NY, United States / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0

A land route westward was needed in the early 1800s, a fact made evident when Ohio became a state and there was no road that went there. And so the National Road was proposed as the first federal highway.

Construction began in western Maryland in 1811. Workers started building the road going westward, and other work crews began heading east, toward Washington, D.C.

It was eventually possible to take the road from Washington all the way to Indiana. And the road was made to last. Constructed with a new system called "macadam," the road was amazingly durable. Parts of it actually became an early interstate highway.

The Erie Canal

Federal Highway Administration / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Canals had proven their worth in Europe, where cargo and people traveled on them, and some Americans realized that canals could bring great improvement to the United States.

Citizens of New York state invested in a project that was often mocked as folly. But when the Erie Canal opened in 1825, it was considered a marvel.

The canal connected the Hudson River, and New York City, with the Great Lakes. As a simple route into the interior of North America, it carried thousands of settlers westward in the first half of the 19th century.

The canal was such a commercial success that soon, New York was being called "The Empire State."

The Oregon Trail

Albert Bierstadt / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

In the 1840s, the way westward for thousands of settlers was the Oregon Trail, which began in Independence, Missouri.

The Oregon Trail stretched for 2,000 miles. After traversing prairies and the Rocky Mountains, the end of the trail was in the Willamette Valley of Oregon.

While the Oregon Trail became known for westward travel in the mid-1800s, it was actually discovered decades earlier by men traveling eastward. Employees of John Jacob Astor , who had established his fur trading outpost in Oregon, blazed what became known as the Oregon Trail while carrying dispatches back east to Astor's headquarters.

Fort Laramie

MPI/Stringer / Getty Images

Fort Laramie was an important western outpost along the Oregon Trail. For decades, it was an important landmark along the trail. Many thousands of emigrants heading to the west passed by it. Following the years of it being an important landmark for westward travel, it became a valuable military outpost.

The South Pass

BLM Wyoming / Flickr / CC BY 2.0

The South Pass was another very important landmark along the Oregon Trail. It marked the spot where travelers would stop climbing in the high mountains and would begin a long descent to the regions of the Pacific Coast.

The South Pass was assumed to be the eventual route for a transcontinental railroad, but that never happened. The railroad was built farther to the south, and the importance of the South Pass faded.

- The National Road, America's First Major Highway

- Biography of Daniel Boone, Legendary American Frontiersman

- Exploration of the West in the 19th Century

- Albert Gallatin's Report on Roads, Canals, Harbors, and Rivers

- Cumberland Gap

- Manifest Destiny: What It Meant for American Expansion

- Building the Erie Canal

- The Growth of the Early US Economy in the West

- Timeline from 1810 to 1820

- The California Gold Rush

- Biography of John C. Frémont, Soldier, Explorer, Senator

- First National Park Resulted From the Yellowstone Expedition

- Abigail Scott Duniway

- American Civil War: Major General John C. Frémont

Module 10: Westward Expansion (1800-1860)

Why it matters: westward expansion.

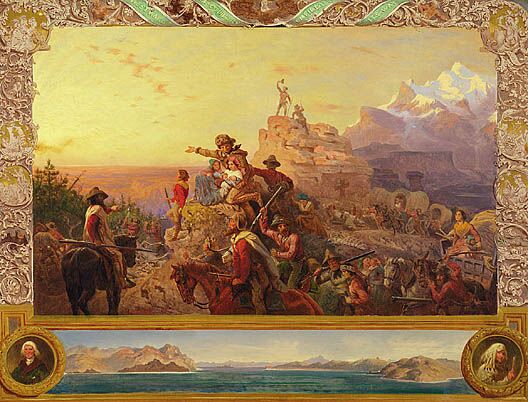

Figure 1 . In the first half of the nineteenth century, settlers began to move west of the Mississippi River in large numbers. In John Gast’s American Progress (ca. 1872), the figure of Columbia, representing the United States and the spirit of democracy, makes her way westward, bringing light to the darkness as she advances.

Why learn about Westward Expansion?

After 1800, the United States expanded westward across North America through a combination of land acquisition and settlement. American pioneers and those who supported them were confident of their right and duty to gain control of the continent and spread the benefits of their “superior” culture to the indigenous populations living in the interior of the country. In John Gast’s American Progress , the White, blonde figure of Columbia—a historical personification of the United States—strides triumphantly westward with the Star of Empire on her head. She brings education, symbolized by the schoolbook, and modern technology, represented by the telegraph wire. White settlers follow her lead, driving the helpless Natives peoples away and bringing successive waves of technological progress in their wake. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the quest for control of the West led to the Louisiana Purchase, the annexation of Texas, and the Mexican-American War. Efforts to seize western territories from Native peoples and expand the republic by warring with Mexico succeeded beyond expectations. Few nations had ever grown so quickly. Yet, this expansion led to debates about the expansion of slavery into the new Western territories, increasing the tension between Northern and Southern states that ultimately led to the Civil War.

- US History. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/11-introduction . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 6

- The Gold Rush

- The Homestead Act and the exodusters

- The reservation system

- The Dawes Act

- Chinese immigrants and Mexican Americans in the age of westward expansion

- The Indian Wars and the Battle of the Little Bighorn

- The Ghost Dance and Wounded Knee

Westward expansion: economic development

- Westward expansion: social and cultural development

- The American West

- Land, mining, and improved transportation by rail brought settlers to the American West during the Gilded Age.

- New agricultural machinery allowed farmers to increase crop yields with less labor, but falling prices and rising expenses left them in debt.

- Farmers began to organize in local and regional cooperatives like the Grange and the Farmers’ Alliance to promote their interests.

Who owns the West?

Developing the west.

- (Choice A) Railroads led to the discovery of profitable minerals. A Railroads led to the discovery of profitable minerals.

- (Choice B) Railroads brought more people to the East Coast. B Railroads brought more people to the East Coast.

- (Choice C) Railroads allowed farmers to sell their goods in distant markets. C Railroads allowed farmers to sell their goods in distant markets.

Farmers in an industrial age

The grange and the farmers’ alliance, what do you think.

- The Homestead Act , 1862.

- See OpenStax, The Westward Spirit , U.S. History, OpenStax CNX, 2019.

- See David M. Kennedy and Lizabeth Cohen, The American Pageant: A History of the American People, 15th (AP) Edition, (Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning, 2013), 584-585.

- Kennedy and Cohen, The American Pageant , 512-513.

- See Eric Foner, Give Me Liberty!: An American History, 5th AP Edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2016), 593.

- Kennedy and Cohen, The American Pageant , 594-596.

- Kennedy and Cohen, The American Pageant , 596-598.

- See Foner, Give Me Liberty! , 641-643.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail is the most famous of the Overland Trails used by thousands of American pioneers who emigrated to Oregon and other western territories during the age of Manifest Destiny and Westward Expansion. It was blazed by frontiersman Robert Stuart in 1812–1813 and was most popular from 1841 to 1869.

The Oregon Trail , Albert Bierstadt, 1869. Image Source: Butler Institute of American Art .

What was the Oregon Trail?

Oregon trail summary.

The Oregon Trail was the most historic of the Overland Trails used by settlers, traders, and others to migrate to the western United States during the 19th century. The trail stretched for more than 2,000 miles from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon City, in present-day Oregon. The trail was originally used by Native American Indians for hunting and trading. Later, it was developed and improved by explorers like Lewis and Clark and Mountain Men like Jedediah Smith and Jim Bridger . The trail gained widespread popularity in the 1840s when thousands of settlers started using it to move west. The trail’s popularity died out after the use of railroads started in the late 1860s, however, it played a significant part in the westward expansion of the United States and the fulfillment of Manifest Destiny.

Oregon Trail Quick Facts

- The Oregon Trail played a significant role in America’s fulfillment of Manifest Destiny .

- It is estimated that as many as 650,000 moved west on the Overland Trails, including the Oregon Trail, from the early 1840s through the end of the Civil War.

- Roughly one-third of those people went to Oregon.

- In total, the Oregon Trail was about 2,000 miles long.

- The desire to move west was called “Oregon Fever.”

- The Oregon Trail passed through the present-day states of Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon.

- The California Trail, Mormon Trail, and Bozeman Trail were all offshoots from the Oregon Trail.

- Wagons were pulled by oxen, not horses, because Indians would only take horses in raids.

Oregon Trail History

Robert stuart finds the south pass through the rocky mountains.

Robert Stuart was a member of the fur trading group known as the Astorians, who worked for John Jacob Astor and the Pacific Fur Company, part of the American Fur Company . Stuart led an expedition to the Oregon Country that established Fort Astoria.

On the journey back to St. Louis, he discovered a path in the southern portion of present-day Wyoming that went over the Continental Divide and through the Rocky Mountains — and could be traveled by wagon. This part of the trail became known as the “South Pass,” because it was south of the route blazed by Lewis and Clark. The trail Stuart followed from Oregon back to St. Louis is what became known as the Oregon Trail.

Stuart and Astor kept the location of the South Pass a secret.

Running east to west, the trail started in Independence, Missouri, stretched west for approximately 2,000 miles, and ended in Oregon City, Oregon. It was not one continuous trail from Missouri to Oregon. It was a series of paths, trails, and wagon roads that often followed old Native American Indian trails. Along the way, it passed through six states including Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon.

Although there were several other westward trails, the Oregon Trail was the most popular. As more people emigrated west, towns along the route became alternate points of departure for the westward journey, including Atchison and Leavenworth in Kansas, St. Joseph and Weston in Missouri, and Omaha in Nebraska.

Jefferson’s Vision and the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Even before Thomas Jefferson became President in 1800, he had dreams of a nation that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. He tried to organize at least two expeditions that never came to fruition. Finally, the opportunity presented itself in 1803 when he received funding from Congress for a secret military expedition that was going to travel west, into French territory. The plan changed a few months later when France offered the Louisiana Territory to the United States. By the time the Lewis and Clark Expedition set sailed up the Missouri River, the Louisiana Purchase had been completed, eliminating concerns about trespassing in French territory. The expedition spent nearly three years exploring the area, and their reports encouraged many others to travel westward.

Hudson’s Bay Company and the Fur Trade

Following the War of 1812 , the British presence in the west increased, primarily through the efforts of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Although the Treaty of 1818 between the United States and Great Britain established “joint occupation” of the Oregon Territory, the Hudson’s Bay Company essentially controlled the area.

However, the United States continued to explore the area west of the Louisiana Territory and sponsored more expeditions, which were led by men like Captain Benjamin Bonneville, John C. Frémont , and Kit Carson. The American expeditions usually stayed south of the Oregon Territory, including Stephen H. Long’s 1820 expedition into the Great Plains . During that expedition, he famously called the plains the “Great American Desert” — which effectively slowed westward migration for a short time.

Carson and other men, like Jim Bridger, Thomas Fitzpatrick , and James Beckwourth became renowned Mountain Men, known for their knowledge of the territory. Not only did they work for the fur trading companies but they also served as scouts for military and emigrant expeditions.

Jedediah Smith Maps the South Pass

Jedediah Smith led an expedition from the Rocky Mountain Fur Company into the Wind River Valley, in central Wyoming, for the winter of 1823–1824. At some point, they located the Crow Indians, who told them about a passage — the “South Pass” — through the Rocky Mountains that would safely take him across the Continental Divide, which ran between the Central and Southern Rocky Mountains.

In February 1824, Smith and his men went through the South Pass and made their way to the Green River in present-day Utah. They stayed there for the spring, trapping along the river and its tributaries.

Smith sent Thomas Fitzpatrick back to St. Louis to deliver the news of the “discovery” to William Henry Ashley, who used the South Pass to establish his Trapper Rendezvous system, which he started in 1825.

In 1830, Smith sent a letter to Secretary of War John Eaton, informing him of the South Pass. This allowed the route to become an important part of the Oregon Trail, as thousands of Americans used it to move west.

Wyeth-Lee Party

The first group of settlers traveled west in 1834, led by Nathaniel Wyeth and Jason Lee. Wyeth was a merchant from New England and Lee was a missionary. Wyeth made the trip to sell supplies at the annual Rocky Mountain Rendezvous, a gathering of Mountain Men in the Rocky Mountains. Lee was headed west to establish a mission to convert Native American Indians to Christianity. The Wyeth-Lee Party was the first to travel the full length of the Oregon Trail.

Marcus and Narcissa Whitman

In 1836, American missionaries, led by Marcus Whitman and his wife, Narcissa, took the Oregon Trail to the Willamette Valley. The Whitman Party was led by Bonneville. During the journey, the Whitmans became the first people to use wagons to make the journey on the trail. Narcissa Whitman also became one of the first Anglo-American women to travel the entirety of the Oregon Trail. Once they arrived in the Willamette Valley, the Whitman’s established a mission that was visited frequently by emigrants on their way west.

Fort Bridger

By 1840, the demand for felt hats decreased, which diminished the fur trade and Britain’s interests in the region. As the fur trade dwindled, many of the Mountian Men lead emigrants across the Great Plains and over the trail to their new homes in Oregon and California. Some, like Jim Bridger, also established trading posts along the Oregon Trail. Bridger’s post, called Fort Bridger, was set up in 1842 on Blacks Fork of the Green River, in present-day Uinta County, Wyoming.

Great Migration of 1843

During the winter of 1842–1843, Marcus Whitman traveled to Boston. On the return trip, he stopped at Independence, where a massive group of emigrants had gathered to make the journey west. This massive wagon train would be the first major migration along the Oregon Trail and became known as the “Great Migration of 1843.” It is estimated there were at least 120 wagons and somewhere between 800 and 1,000 men, women, and children.

Whitman did not go with the wagon train when it left for Oregon. He traveled to visit missions in the Great Plains but promised to meet them along the Platte River. John Gantt led the group until Whitman met up with them, and then Whitman led them to the Columbia River.

Until then, no one had been able to travel the full length of the Oregon Trail in wagons. When expeditions reached Fort Hall in the eastern portion of the Oregon Territory, they were forced to abandon wagons and finish the trip on pack animals. Whitman convinced the members of the wagon train they could take their wagons with them. When the wagon train arrived near Mount Hood, the wagons were taken apart and floated down the Columbia River. By October, the emigrants arrived in the Willamette Valley.

From then until 1846, when a new road — the Barlow Road — was opened in the territory, allowing emigrants to travel the entire distance of the Oregon Trail by wagon.

Oregon Treaty

Following the Great Migration of 1843, emigration to Oregon increased and the call for the United States to take full control of the Oregon Territory grew, as supporters used the slogan, “54 degrees 40 minutes or fight!”

President James K. Polk , a firm supporter of the concept of America’s Manifest Destiny, made a proposition to British officials to establish a boundary along the 49th parallel. Secretary of State James Buchanan and Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina worked with British officials to design the Oregon Treaty of 1846. Per the treaty, all of Vancouver Island was given to Canada, and the United States was given the lower portion of the territory, which comprised present-day Washington and Oregon. The treaty was ratified by the Senate on June 18, 1846.

Later Years on the Oregon Trail

Thousands of Americans streamed west to Oregon and California over the Oregon Trail following the Oregon Treaty. Some of the key events included:

- 1846 — The Donner Party became stranded in the Sierra Nevada Mountains during the winter.

- 1847 — Brigham Young led the Mormon Brigade to Utah.

- 1849 — Following the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in California, an estimated 30,000 emigrants went west at the onset of the California Gold Rush . At least 55,000 followed in 1850.

- 1851 — Congress passed the Donation Land Act, which granted land to settlers in Oregon and incentivized immigration.

- 1854–1857 — Immigration slowed due to the Indian Wars.

- 1858 — Gold was discovered in Colorado.

- 1859 — The first stagecoaches were used on the trail.

- 1860 — Silver was found in Nevada and the Pony Express started.

- 1863 — Gold was found in Montana and the Pony Express went bankrupt.

- 1866–1869 — The era of the overland trails came to an end with the railroads.

Interesting Facts About the Oregon Trail

Prairie schooners.

Emigrants primarily traveled the Oregon Trail in covered wagons, known as “Prairie Schooners.” They were built out of wood and iron and covered with waterproofed cotton or linen canvas. The wagons were usually about 10 feet long, and 4 feet wide, and could weigh up to 2,500 pounds when fully loaded. The pioneers often walked alongside the wagons, which were pulled by oxen or mules.

The wagons were typically loaded with enough food to finish the trip to the West Coast and included preserved foods, including hard tack, bacon, coffee, flour, beans, and rice. They also carried critical supplies, such as cooking utensils, clothing, candles, a rifle, tents, bedding, axes, and shovels.

They were called schooners as a reference to small sailing ships.

A Treacherous Journey

The journey was dangerous. The pioneers were exposed to harsh weather, threats from wild animals, and attacks from Native American Indians. Clean water was often an issue, and unsanitary conditions contributed to the spread of diseases, which led to the deaths of many settlers.

Destinations Other than Oregon

Despite the dangers, many people made the journey in search of new opportunities and a better life in the western territories. The Oregon Trail was the most popular of the westward wagon trails, but there were others. Some of them branched off the Oregon Trail, such as the California Trail , which left the Oregon Trail in Idaho and headed south to California, and the Mormon Trail, which went from Council Bluffs, Iowa to Salt Lake City, Utah.

Oregon National Historic Trail

The Oregon Trail was popular until the Transcontinental Railroad connected the East to the West in 1869. In 1978, the U.S. Congress officially named the trail the Oregon National Historic Trail. Although much of the trail has been built over, around 300 miles of the trail have been preserved and can still be visited today.

Why was the Oregon Trail Important?

Oregon trail significance.

The Oregon Trail is important to United States history because it provided a vital path for westward expansion in the United States. The trail was used by hundreds of thousands of people in the 19th century. It played a key role in the settlement and development of the American West and will forever be linked with the concept of Manifest Destiny and Westward Expansion.

Oregon Trail APUSH

Use the following links and videos to study the Oregon Trail, Manifest Destiny, and Westward Expansion for the AP US History (APUSH) exam. Also, be sure to look at our Guide to the AP US History Exam .

Oregon Trail Definition

The definition of the Oregon Trail for APUSH is a vital overland route to the western United States that extended from Missouri to the Oregon Territory. The trail was discovered in 1812, and then opened to emigration in the 1840s. Over the next 25 years, it is estimated that 500,000-650,000 people moved west on the Overland Trails, including the Oregon Trail.

Oregon Trail FAQs

Why was the Oregon Trail important for the settlement of the West?

The Oregon Trail was important to the settlement of the West because the eastern portion of the trail served as the main path westward for most emigrants. Several other Overland Trails branched off of it, including the California Trail, Mormon Trail, and Bozeman Trail. The Oregon Trail played an important role in America’s Manifest Destiny .

What was the most common cause of death on the Oregon Trail?

It is estimated that nearly one in every ten people died on the trail. The most common causes of death were sickness, particularly cholera, and accidents.

What was it like to be on the Oregon Trail?

This video from Weird History explores what it was like for pioneers on the Oregon Trail.

- Written by Randal Rust

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Lewis and Clark Expedition

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 28, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Lewis and Clark Expedition began in 1804, when President Thomas Jefferson tasked Meriwether Lewis with exploring the lands west of the Mississippi River that comprised the Louisiana Purchase. Lewis chose William Clark as his co-leader for the mission. The excursion lasted over two years. Along the way they confronted harsh weather, unforgiving terrain, treacherous waters, injuries, starvation, disease and both friendly and hostile Native Americans. Nevertheless, the approximately 8,000-mile journey was deemed a huge success and provided new geographic, ecological and cultural information about previously uncharted areas of North America.

Who Were Lewis and Clark?

Meriwether Lewis was born in Virginia in 1774 but spent his early childhood in Georgia . He returned to Virginia as a teenager to receive his education and graduated from college in 1793. He then joined the Virginia state militia—where he helped to put down the Whiskey Rebellion —and later became a captain in the U.S. Army. At age 27 he became personal secretary to President Thomas Jefferson .

William Clark was also born in Virginia in 1770 but moved with his family to Kentucky at age 15. At age 19, he joined the state militia and then the regular Army, where he served with Lewis and was eventually commissioned by President George Washington as a lieutenant of infantry.

In 1796, Clark returned home to manage his family’s estate. Seven years later, Lewis chose him to embark on the epic excursion that would help shape America’s history.

Louisiana Purchase

During the French and Indian War , France surrendered a large part of Louisiana to Spain and almost all of its remaining lands to Great Britain.

Initially, Spain’s acquisition didn’t have a major impact since it still allowed the United States to travel the Mississippi River and use New Orleans as a trade port. Then Napoleon Bonaparte took power in France in 1799 and wanted to regain France’s former territory in the United States.

In 1802, King Charles IV of Spain returned the Louisiana Territory to France and revoked America’s port access. In 1803, under the threat of war, President Jefferson and James Monroe successfully negotiated a deal with France to purchase the Louisiana Territory—which included about 827,000 square miles—for $15 million.

Even before negotiations with France were finished, Jefferson asked Congress to finance an expedition to survey the lands of the so-called Louisiana Purchase and appointed Lewis as expedition commander.

Preparations for the Lewis and Clark Expedition

preparations immediately. He studied medicine, botany, astronomy and zoology and scrutinized existing maps and journals of the region. He also asked his friend Clark to co-command the expedition.

Even though Clark was once Lewis’ superior, Lewis was technically in charge of the trip. But for all intents and purposes, the two shared equal responsibility.

On July 5, 1803, Lewis visited the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry to obtain munitions. He then rode a custom-made, 55-foot keelboat—also called “the boat” or “the barge”—down the Ohio River and joined Clark in Clarksville, Indiana . From there, Clark took the boat up the Mississippi River while Lewis continued along on horseback to collect additional supplies.

Some of the supplies collected were:

- surveying instruments including compasses, quadrants, telescope, sextants and a chronometer

- camping supplies including oilcloth, steel flints, tools, utensils, corn mill, mosquito netting, fishing equipment, soap and salt

- weapons and ammunition

- medicines and medical supplies

- books on botany, geography and astronomy

Lewis also collected gifts to present to Native Americans along the journey such as:

- ivory combs

- bright colored cloth

- sewing notions

Corps of Discovery

Lewis entrusted Clark to recruit men for their “Corps of Volunteers for Northwest Discovery,” or simply the Corps of Discovery. Throughout the winter of 1803-1804, Clark recruited and trained men at Camp DuBois north of St. Louis, Missouri . He chose unmarried, healthy men who were good hunters and knew survival skills.

The expedition party included 45 souls including Lewis, Clark, 27 unmarried soldiers, a French-Indian interpreter, a contracted boat crew and an enslaved person owned by Clark named York.

On May 14, 1804, Clark and the Corps joined Lewis in St. Charles, Missouri and headed upstream on the Missouri River in the keelboat and two smaller boats at a rate of about 15 miles per day. Heat, swarms of insects and strong river currents made the trip arduous at best.

To maintain discipline, Lewis and Clark ruled the Corps with an iron hand and doled out harsh punishments such as bareback lashing and hard labor for those who got out of line.

On August 20 of that year, 22-year-old Corps member Sergeant Charles Floyd died of an abdominal infection, possibly appendicitis. He was the only member of the Corps to die on their journey.

Native American Encounters

Most of the land Lewis and Clark surveyed was already occupied by Native Americans. In fact, the Corps encountered around 50 different Native American tribes including the Shoshone, the Mandan, the Minitari, the Blackfeet, the Chinook and the Sioux .

Lewis and Clark developed a first contact protocol for meeting new tribes. They bartered goods and presented the tribe’s leader with a Jefferson Indian Peace Medal, a coin engraved with the image of Thomas Jefferson on one side and an image of two hands clasped beneath a tomahawk and a peace pipe with the inscription, “Peace and Friendship” on the other.

They also told the Indians that America owned their land and offered military protection in exchange for peace.

Some Indians had met “white men” before and were friendly and open to trade. Others were wary of Lewis and Clark and their intentions and were openly hostile, though seldom violent.

In August, Lewis and Clark held peaceful Indian councils with the Odo, near present-day Council Bluffs, Iowa , and the Yankton Sioux at present-day Yankton, South Dakota .

In late September, however, they encountered the Teton Sioux, who weren’t as accommodating and tried to stop the Corps’ boats and demanded a toll payment. But they were no match for the military weapons of the Corps, and soon moved on.

Fort Mandan

In early November, the Corps came across villages of friendly Mandan and Minitari Indians near present-day Washburn, North Dakota , and decided to set up camp downriver for the winter along the banks of the Missouri River.

Within about four weeks they’d built a triangular-shaped fort called Fort Mandan , which was surrounded by 16-foot pickets and contained quarters and storage rooms.

The Corps spent the next five months at Fort Mandan hunting, forging and making canoes, ropes, leather clothing and moccasins while Clark prepared new maps. According to Clark’s journal, the men were in good health overall, other than those suffering from sexually transmitted infections.

While at Fort Mandan, Lewis and Clark met French-Canadian trapper Toussaint Charbonneau and hired him as an interpreter. They allowed his pregnant Shoshone wife, Sacagawea , to join him on the expedition.

Sacagawea had been kidnapped by Hidatsa Indians at age 12 and then sold to Charbonneau. Lewis and Clark hoped she could help them communicate with any Shoshone they’d encounter on their journey.

On February 11, 1805, Sacagawea gave birth to a son and named him Jean Baptiste. She became an invaluable and respected asset for Lewis and Clark.

The Continental Divide

On April 7, 1805, Lewis and Clark sent some of their crew and their keelboat loaded with zoological and botanical samplings, maps, reports and letters back to St. Louis while they and the rest of the Corps headed for the Pacific Ocean.

They crossed through Montana and made their way to the Continental Divide via Lemhi Pass where, with Sacagawea’s help, they purchased horses from the Shoshone. While there, Sacagawea reunited with her brother Cameahwait, who hadn’t seen her since she was kidnapped.

The group next headed out of Lemhi Pass and crossed the Bitterroot Mountain Range using the harrowing Lolo Trail and the help of many horses and a handful of Shoshone guides.

This leg of the journey proved to be the most difficult. Many of the party suffered from frostbite, hunger, dehydration, bad weather, freezing temperatures and exhaustion. Still, despite the merciless terrain and conditions, not a single soul was lost.

After 11 days on the Lolo Trail, the Corps stumbled upon a tribe of friendly Nez Perce Indians along Idaho’s Clearwater River. The Indians took in the weary travelers, fed them and helped them regain their health.

As the Corps recovered, they built dugout canoes, then left their horses with the Nez Perce and braved the Clearwater River rapids to Snake River and then to the Columbia River. They reportedly ate dog meat along the way instead of wild game.

Fort Clatsop

A bedraggled and harried Corps finally reached the stormy Pacific Ocean in November of 1805. They’d completed their mission and had to find a place to live for the winter before heading home.

They decided to make camp near present-day Astoria, Oregon , and started building Fort Clatsop on December 10 and moved in by Christmas .

It was not an easy winter at Fort Clatsop. Everyone struggled to keep themselves and their supplies dry and fought an ongoing battle with tormenting fleas and other insects. Almost everyone was weak and sick with stomach problems (likely caused by bacterial infections), hunger or influenza-like symptoms.

Lewis and Clark Journey Home

On March 23, 1806, the Corps left Fort Clatsop for home. They retrieved their horses from the Nez Perce and waited until June for the snow to melt to cross the mountains into the Missouri River Basin.

After again traversing the rugged Bitterroot Mountain Range, Lewis and Clark split up at Lolo Pass.

Lewis’ group took a shortcut north to the Great Falls of the Missouri River and explored Marias River—a tributary of the Missouri in present-day Montana—while Clark’s group, including Sacagawea and her family, went south along the Yellowstone River. The two groups planned to rendezvous where the Yellowstone and Missouri met in North Dakota.

HISTORY Vault: Lewis and Clark: Explore New Frontier

Discover the adventures of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark as they traversed the vast, unknown continent of North America.

Pompey’s Pillar

On July 25, 1806, Clark carved his name and the date on a large rock formation near the Yellowstone River he named Pompey’s Pillar , after Sacagawea’s son whose nickname was “Pompey.” The site is now a national monument managed by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Two days later, at Marias River near present-day Cut Bank, Montana, Lewis and his group encountered eight Blackfeet warriors and were forced to kill two of them when they tried to steal weapons and horses. The location of the clash became known as Two Medicine Fight Site.

It was the only violent episode of the expedition, although soon after the Blackfeet fight, Lewis was accidentally shot in his buttocks during a hunting trip; the injury was painful and inconvenient but not fatal.

On August 12, 1806, Lewis and Clark and their crews reunited and dropped off Sacagawea and her family at the Mandan villages. They then headed down the Missouri River—with the currents moving in their favor this time—and arrived in St. Louis on September 23, where they were received with a hero’s welcome.

Legacy of the Expedition

Lewis and Clark returned to Washington, D.C. , in the fall of 1806 and shared their experiences with President Jefferson.

While they had failed to identify a coveted Northwest Passage water route across the continent, they had completed their mission of surveying the Louisiana Territory from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, and did so against tremendous odds with just one death and little violence.

The Corps had traveled more than 8,000 miles, produced invaluable maps and geographical information, identified at least 120 animal specimens and 200 botanical samples and initiated peaceful relations with dozens of Native American tribes.

Both Lewis and Clark received double pay and 1,600 acres of land for their efforts. Lewis was made Governor of the Louisiana Territory and Clark was appointed Brigadier General of Militia for Louisiana Territory and a federal Indian Agent.

Clark remained well-respected and lived a successful life. Lewis, however, was not an effective governor and drank too much. He never married or had children and died in 1809 of two gunshot wounds, possibly self-inflicted. A few years later, Sacagawea died, and Clark became her children’s guardian.

Despite Lewis’ tragic end, his expedition with Clark remains one of America’s most famous. The duo and their crew—with the aid of Sacagawea and other Native Americans—helped strengthen America’s claim to the West and inspired countless other explorers and western pioneers.

Building Fort Clatsop. Discovering Lewis & Clark. Corps of Discovery. National Park Service: Gateway Arch. Expedition Timeline. Thomas Jefferson Foundation: The Jefferson Monticello. Flagship: Keelboat, Barge or Boat? Discovering Lewis & Clark. Fort Clatsop Illnesses. Discovering Lewis & Clark. Fort Mandan Winter. Discovering Lewis & Clark. Indian Peace Medals. Thomas Jefferson Foundation: The Jefferson Monticello. Lemhi Valley to Fort Clatsop. Discovering Lewis & Clark. Lolo Trail. National Park Service: Lewis and Clark Expedition. Louisiana Purchase. Thomas Jefferson Foundation: The Jefferson Monticello. The Journey. National Park Service: Lewis and Clark Expedition. The Native Americans. PBS. To Equip an Expedition. PBS. Two Medicine Fight Site. National Park Service: Lewis and Clark Expedition. Washington City to Fort Mandan. Discovering Lewis & Clark.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

19th Century Transportation Movement

Westward expansion and the growth of the United States during the 19th century sparked a need for a better transportation infrastructure. At the beginning of the century, U.S. citizens and immigrants to the country traveled primarily by horseback or on the rivers. After a while, crude roads were built and then canals. Before long the railroads crisscrossed the country moving people and goods with greater efficiency. This caused distinct regional economies to form and, by the turn of the century, a national economy.

Travel through these technological developments during the 19th Century Transportation Movement with the selected classroom resources.

Human Geography, Social Studies, U.S. History

Why Did People Move West in the 1800s?

By Karen Harris Last updated May 17, 2023

When the first Europeans arrived on the eastern shores of North America, they could scarcely comprehend the vast wilderness that stretched for thousands of miles to the Pacific Ocean far to the west.

The new Americans, however, were not content to stay in one place, as census records show us.

Packing up one’s family and heading off into the unknown must have been a frightening endeavor. We know that the westward migration was fraught with danger: accidents and injuries were common, as were illnesses.

The pioneers encountered Native Americans, many of whom were hostile. The terrain was treacherous, and the weather was unpredictable. In all, the journey could be brutal and deadly. Yet, as much as 40% of the U.S. population participated in the migration, to some degree.

The answer to that question is quite simple.

They felt pulled to the West by some factor or another, or they felt pushed to leave their current home in the East for various reasons. The lure of the West beckoned many pioneers with the promise of untapped resources, fertile land, adventure, freedom, and open spaces. Others migrated to the West to escape poverty, crowded cities, or political or religious persecution.

One of the biggest factors that contributed to the western migration, however, was the idea of Manifest Destiny . The prevailing national attitude of the 1800s, Manifest Destiny, was the belief that the American way of life was destined by God to spread across the North American continent.

To understand why people risked everything to move west in the 1800s, we need to understand Manifest Destiny, as well as the factors that pulled and pushed settlers to join the migration.

Read next : The Many Lives of Olive Oatman, Tattooed Captive of the West

Start of the Western Migrations

Under President Thomas Jefferson, the United States more than doubled in size after the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Jefferson envisioned a healthy American society, growing and expanding westward into the uncharted wilderness.

The American public seemed to agree.

According to census records, less than 10% of American citizens lived west of the Appalachian Mountains in 1800. Two dozen years later, that number increased to 30% of the country’s population.

Throughout the early and mid-1800s, census records show that roughly half of all American citizens moved to new locations from census to census, proving that westward mobility was in full swing.

Related read : 14 Facts About the Mormon Migration, A Classic Old West Exodus

Manifest Destiny and the Western Migration

In 1845, newspaper publisher John O’Sullivan used a new term — manifest destiny — to describe the prevailing attitude of the day. According to Manifest Destiny, God bestowed special virtues on the American people.

It was the belief that America was destined by God to spread across the entire North American continent. The American people were preordained to settle the western frontier with vast farms and ranches. Manifest Destiny was meant to be, the concept held. It would be wrong to not join the Western Migration, according to the precepts of Manifest Destiny.

Manifest Destiny was used to justify the various wars and conflicts that the United States fought in the early to mid-1800s. These wars, including battles against Native America, as well as the Mexican-American War , were fought to oust non-Americans from lands in the western wilderness.

The American people felt justified in removing the Native Americans from their ancestral lands because they strongly believed that they were acting according to God’s plans.

Related read : 7 Tantalizing Stories of Lost Treasure in Oregon

A Dangerous Journey West

The Western frontier was a dangerous place. There were Native American tribes, many of which were hostile to white settlers. There were swift-moving rivers, dense forests, vast grasslands, brutal deserts, and unforgiving mountains.

Pioneers died crossing rivers or succumbed to deadly thirst in the deserts. Others were killed by bears, rattlesnakes, or wolves. There were no doctors or hospitals in the western wilderness. If someone was injured or fell ill, they could not get medical help.

People died from fevers, infections, and in childbirth.

Related read : 10 Wild West Facts of Everyday Life on the Frontier

The Pull and Push of Western Migration

The dangers of traveling into the west were well known, yet thousands of families and individuals took the risk. They uprooted their families and sold their properties so they could head west into the dangerous unknown.

Why? Certainly, the belief in Manifest Destiny could account for many of the pioneers, but it was only one of the reasons for Western Migration . The other reasons can be divided into two categories: reasons that pulled, or attracted, people to the West, and reasons that pushed them out of the East.

Related read : Chuckwagon Chow: 8 Cattle-Drive Foods Cowboys Ate on the Trail

The Pull of the West

America was the land of opportunity, and, for many pioneers, the West held endless possibilities. Looking for a better life, these pioneers envisioned a life of freedom and prosperity in the homesteads they would carve out of the wilderness.

Many of them wanted to raise their children away from the crowded and dirty cities of the east. They also wanted more control over their lives and their futures. As westward pioneers, their success would be tied to their own hard work, determination, and ingenuity — not the whims of their factory bosses.

Following Families West

A good many settlers moved West to join family or friends who had made the journey ahead of them. They probably received letters back from their loved ones detailing the rich resources and fertile land of the West and inviting them to join them on the frontier.

Starting a new life in the unknown land of the west would be easier for a larger group than an individual family, so it was not uncommon for families to travel west to rejoin their loved ones.

Riches & Opportunities of the West

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 sparked a mass migration of American settlers. For them, the lure of easy wealth outweighed the perils of the journey itself. Gold was not the only valuable resource.

Silver, copper, and other valuable metals were discovered in the West. Stories of prospectors striking it rich were published in the newspapers back East, making it seem as though immense wealth awaited anyone who traveled west.

In reality, very few people struck it rich during the Gold Rush, but that didn’t stop the waves of people from rushing to California to try their luck.

For many Americans living in the eastern cities in the 1800s, life was boring and tedious. Thomas Jefferson, among others, called the American West a new “Garden of Eden,” full of promise.

Stories and news articles painted life in the West as exciting and adventurous. The West beckoned adventure-seekers. People who wanted the challenge of pioneer life and the opportunity to commune with nature were drawn to the western wilderness.

Related read : 9 Reasons Why Fort Bridger was the Worst Fort on the Oregon Trail

Homesteading Land

Aside from the California Gold Rush , perhaps the biggest reason why people migrated to the West in the 1800s was to get free land.

Under the Homestead Act of 1862 , signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln, any adult could receive a grant for 160-acre homestead parcels west of the Mississippi River, providing they had never taken up arms against the U.S. in the past.

A homesteader only needed to live on the land and improve it for five years and then the government would transfer ownership of the land to the homesteader.

Even women, immigrants, and freed slaves could apply for land.

For African Americans and other oppressed groups, this was the only opportunity for land ownership. According to historical records, about one-fourth of all black farmers owned their own land by the end of the 1800s, thanks largely to the Homestead Act. Nearly ten percent of the United States, more than 1.6 million acres, was given away for free via the Homestead Act.

The Push of the East

For many Americans in the 1800s, the West offered an escape from the drudgery of their lives in the East. They did not necessarily feel drawn to the western frontier so much as they felt pushed out of their current homes for various reasons. They did not want to stay in their present location, and the best option available to them was to head west.

Economic factors were one of the biggest contributing factors.

In the cities of the East, Americans had to compete for jobs and housing with newly arrived immigrants, as well as their neighbors. Good-paying, steady jobs were hard to come by. With no government regulations over the workplace, factory workers toiled in unsafe and horrific conditions, clocking in long hours with no breaks and no days off.

Wages were low, keeping most factory workers living on the edge of poverty. The workers could see that there was little hope for an improvement to their economic situation if they stayed in the East. Their best hope for a brighter future was to move west.

The cities in the East grew rapidly. They were crowded and dirty and, in many cases, riddled with crime. Youngsters were often recruited to work in the factories alongside their parents or were left to roam the streets unsupervised. Families didn’t want to raise their children in such a place. They could not sufficiently improve their surroundings, but they could leave the cities and head west.

Leaving the Troubles of the East

Diseases spread quickly in the crowded cities, especially among factory workers. Doctors often prescribed fresh air and sunshine as cures for various ailments. It was not uncommon for folks to make the move to the West for health reasons and to leave the disease-filled cities behind.

Even though the United States was founded on the principle of religious and political tolerance, discrimination was rampant in the eastern cities of the 1800s. Many pioneers moved to the West to escape religious, political, and social persecution and harassment.

One notable group that fled to the West were the Latter-Day Saints, but they were certainly not the only ones. Catholics and Jews also ventured to the western frontier. Individuals, as well as groups, left the East for these reasons.

People in the West were more tolerant of mixed marriages, spinster women, and ex-cons — those who would not have fit easily into society in the East.

Last, there was an emerging anti-modernization movement growing in the country at the time. As factories grew larger and more machines were brought in, many people blamed the new technology for corrupting the traditional American way of life.

They sought to flee from the evils of modern times and live more simply, and westward expansion offered an escape.

Related : Cowboy & Western Name Generator

Westward Expansion: Fulfilling Manifest Destiny

With so many Americans moving to the western frontier during the 1800s, the United States realized its goal of spreading the American ideology from sea to shining sea.

For better or worse, Manifest Destiny had been fulfilled.

The Western Migration can be compared to European colonialism , however, as the spread of white settlers came at the expense of many native populations. The end result was a nation that extends from one side of the continent to the other, that has grown wealthy and prosperous thanks to the abundant natural resources of the West.

Read more about life in the Old West:

- Westward Ho: Daily Life on the Oregon Trail

- Register Cliff: Where Pioneer Graffiti Becomes an Historic Time Capsule

- Hope Deferred: 16 Iconic Landmarks on the Oregon Trail

- Prairie Pioneers: True & Inspiring Oregon Trail Stories

- Hell on Wheels History: Rowdy Railroad Towns Across the Plains

Further Reading

- Dreams of El Dorado: A History of the American West , H.W. Brands

- The Age of Gold: The California Gold Rush and the New American Dream , H.W. Brands

- Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson and the Opening of the American West , Stephen E. Ambrose

- Blood and Treasure: Daniel Boone and the Fight for America’s First Frontier , Bob Drury & Tom Clavin

- The Earth Is Weeping: The Epic Story of the Indian Wars for the American West , Peter Cozzens

by Karen Harris

Although Karen lives in the Midwest, she likes to put the emphasis on the "west." A freelance writer who specializes in American history, Karen has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Central Michigan University and a master's degree in English from Indiana University.

Discussion (1)

One response to “why did people move west in the 1800s”.

thank you this was very helpful!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Related Posts

7 Facts You May Not Know About the Conestoga Wagon

The Conestoga wagon was an icon of Western expansion, but it is often misunderstood. Conestoga wagons were important…

When Did the Wild West Really End?

The Wild West is a more nebulous term than you may think, so when the era ended is…

17 Epic Facts about the Transcontinental Railroad

When the Golden Spike connected Central Pacific and Union Pacific rails at Promontory Summit, Utah, in May 1869,…

14 Vintage Old West Magazines You Can Still Find Today

The 1960s and ’70s ushered in a golden era of Old West magazine publishing, and today these aged-but-entertaining…

29 Most Iconic Quotes from ‘Tombstone’

The classic 1993 Western Tombstone is full of memorable quotes from Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday and the infamous…

- American History

- Ancient History

- European History

- Military History

- Medieval History

- Latin American History

- African History

- Historical Biographies

- History Book Reviews

- Sign in / Join

The Wagon Train: Emigrant Travel in the American West

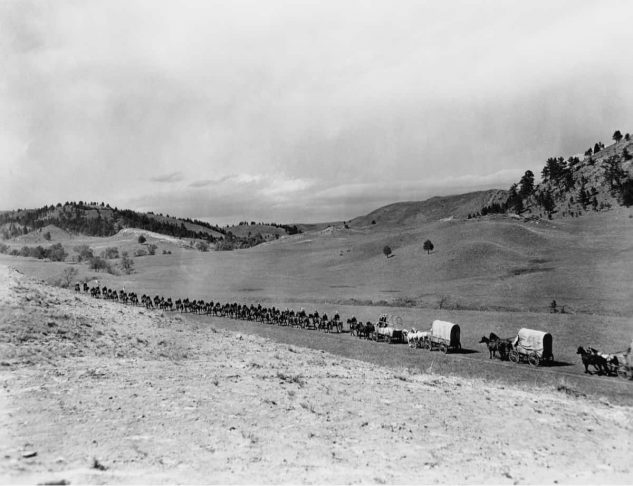

Large groups of covered wagons often traveled together in the American West for protection and mutual support.

There were many reasons why emigrants headed west in the 19th century, beginning with the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1803. In the 1830s, politicians started encouraging Americans to move to Oregon in an effort to discourage settlement by the British. In 1848, gold was discovered in California. And in 1862, the United States Congress passed the Homestead Act, granting permission to families to settle on parcels of 160 acres and earn ownership of the land by cultivating the fields. The Great Western Migration lasted until the late 1800s and emigrants took advantage of these opportunities for land and riches by traveling to their destinations in large groups of covered wagons, or wagon trains.

Organizing a Wagon Train

Wagon trains were organized wherever people decided to band together and head west, but Independence, Missouri quickly gained a reputation as the perfect starting point for emigration. In the 1820s, merchants and tradesmen set up shops in this town offering wagons, draft animals, and supplies to travelers. However, many families filled their wagons and started their journey from their former homes and Independence was simply the place where they joined the train. Once the families met in Independence and agreed to travel together, they often established temporary governments. Some were quite formal with written constitutions and courts of appeal.

Leaders and Guides

The wagon train was led by a Wagon Master, or Captain, who had the grand distinction of signaling the start of the trip. He was the alarm clock for the emigrants, checking in with the families to make sure everyone was up and moving in the mornings, which made him a little less popular. He also made the major travel decisions, such as when to take breaks and camp for the night. By the mid 19th century there were dozens of guidebooks published to aid travelers, but some of these guides offered bad advice and placed emigrants in perilous situations, so wagon trains also had scouts, or guides. Guides were mountain men, fur trappers, and traders who knew the trails.

Moving the Wagons along the Trail

Wagon Masters learned quickly that wagon trains were easily managed if they were limited in size to somewhere between twenty and forty wagons. However, in the early years of westward emigration, some trains were as large as 100 wagons. Wagons often left or joined trains on the journey, particularly if there was an argument among families. When moving, wagons generally traveled in a straight line and drivers sometimes allowed a bit of distance between each wagon, or even drove them side by side, to reduce the amount of dust. At night, the wagons formed a circle for protection from wind, bad weather, bandits and Native American Indian attacks, and the animals were kept inside the circle to prevent theft.

Although emigrants are portrayed in films traveling in large Conestoga Wagons with their tilted front and rear, these wagons were generally used by merchants, who also traveled in wagon trains on occasion. The preferred method of transportation for emigrant families was the lightweight Prairie Schooner. The Prairie Schooner required fewer draft animals, reducing the expense of travel, but it had a maximum weight of 1600 pounds. Therefore, the driver of the wagon walked alongside the oxen and other family members walked beside or behind the wagon so they could pack more supplies without taxing the animals.

Draft Animals

To pull their wagons, emigrants could choose between horses, mules and oxen. Horses were faster, but they required costly grains for feed and were easily stolen at night. Mules were hard-working creatures, but also more expensive. The most popular draft animal was oxen. Though sources vary in reporting the cost of draft animals, according to Time Life Books The Old West: The Pioneers, a mule cost $90 in the 1840s, but an Ox was only $50. Oxen were also slow movers and less likely to be stolen.

- Nevin, David. The Old West: The Pioneers. Time Life Books. Canada: 1974.

- “Westward Ho!” The Real West. The History Channel. 9 Jun 2008

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

McCarthy and Stalin – Political Brothers?

Why the United States Entered World War I

123rd Machine Gun Battalion in the Meuse-Argonne

Northern Military Advantages in the Civil War

The Year Before America Entered the Great War

Causes of the 1937-1938 Recession

- Pantone Colors

Notes From The Frontier

- Oct 21, 2019

What Pioneers Packed to Go West

Updated: May 11, 2023

Pioneers packed like their lives depended on it, because they did!

Westering pioneers had many routes to choose from but the main ones were the Oregon, California, Sante Fe, and Mormon Trails. Whatever route they chose, many read guidebooks like Landsford Hastings’ 1845 “The Emigrant’s Guide to Oregon and California” or Captain Randolph Marcy’s 1859 “The Prairie Traveler: A Hand-Book for Overland Expeditions.” They offered advice on what and how to pack, what draft animals to buy, distances, water, grass, terrain, weather, firearms and ammunition, tools, wagon parts, how to make repairs, and what hardships they might meet along the way.

Two primary types of wagons were used on wagon trails going west. The Conestoga wagon was named for Conestoga Township in Pennsylvania where many German pioneers in the 1750s first started West on the Appalachian Trail to settle land east of the Mississippi. It was a huge and very heavy wagon, 28 feet long with wheels five feet tall and, loaded, could weigh as much as six tons and took three pair of oxen to pull. (Like pulling a semi!)

Later, the much smaller Prairie Schooner became most common on the Oregon, California and Sante Fe Trails to the Western frontier. It was usually built in the Midwest for the departure points in Missouri, where all three trails started. The prairie schooner was half the size of the Conestoga, 12-13 feet long, and weighed 1,300 pounds empty and as much as two tons loaded. It required less animals to pull and to feed on the trail and could move faster (20 miles a day vs. 13-15 for the Conestoga wagon).

The sides of the wagons were waterproofed with tar, so they could ford rivers and keep the cargo dry. A thoroughly water-proofed wagon would also float in high water, making the crossing much easier. The canvas tops were oiled to keep out the rain. Wooden wheels had iron rims to prevent wear.

The Oregon Trail took roughly four to six months to complete. Packing could mean the difference between life and death on the trail and varied wildly depending upon the sensibilities (and sometimes the sense!) of the travelers. James Miller’s 1848 diary entry describes what they packed for food: “We had… 200 lbs. flour for each person, 100 lbs. bacon, corn meal, dried apples and peaches, beans, salt, pepper, rice, tea, coffee, sugar, and many smaller articles for such a trip.” Pioneers also commonly packed 80 lbs. lard, 20 lbs. sugar, 10 lbs. each of coffee and salt per person, yeast, hardtack and crackers.

A wagon was filled with essentials, so travelers usually walked alongside the wagons. This also saved the energy of the oxen, mules or horses pulling the wagons. Teams grazed at night for grass.

Some travelers brought cattle to butcher along the way. Many brought a milk cow and a chicken or two for eggs. Each morning, after milking the cow, the buckets of milk were covered and hung under the wagon. The jarring of the unsprung axle would churn the milk! At night, the fresh butter would be skimmed off. A Dutch oven was the standard cooking container because it was versatile and could be used to bake bread, cook soups, grill meat, and make oatmeal in the morning.

Most wagons had a “chuck box” at the back of the wagon that consisted of a fold-down table surface in front of a cabinet that contained food stuffs, utensils, plates and basics needed to prepare a meal. Shelving below the axle contained larger Dutch ovens, bowls for making bread dough, tubs for washing, or even bottles of a more sundry nature.

Large wooden water kegs were carried on the sides of the wagons. Water would be resupplied from rivers along the way. However, there were some dry stretches and water was carefully preserved. Cholera epidemics were most common along the Platte River and were caused by contaminated water from the massive numbers of travelers that bivouacked there.

Medical and surgical supplies were essential: bandages, ointment, laudanum, cough syrups that contained cocaine, painkillers that contained opium, and of course alcohol for drinking. (Alcohol as an antiseptic was not commonly used until the 1890s.) Surgical instruments for suturing wounds, pulling teeth, lancing boils, extracting bullets or arrowheads, and a bone saw for amputating were commonly packed as well.

Tools for repairing or rebuilding wheels, axles, wagons, ox bows, and harnesses were heavy but crucial to have. The basics were hammers, saws, augers and gimlets. Prudent planners would also pack heavy rope, chains, spare parts, axle grease, and even pulleys. Oil and candle lanterns were essential since work and repairs often had to be done at night, so all would be ready when the wagon train left in the morning.

Warm clothing for rain and cold was packed, as was bedding. Although bedding took up space, it was crucial to get as much sleep as possible. Travelers walked about 20 miles a day over often rough terrain, or in prairie grass as tall as they were, and were exhausted at the end of each day.

Those who insisted on packing iron stoves, heavy furniture, pianos, sewing machines, iron plows, kegs of whiskey, blacksmith anvils, or other weighty items usually discarded them on the side of the trail as the grazing and water ran out. Fort Laramie in Wyoming became known as “Camp Sacrifice” because it was so littered with jettisoned cargo, antique furniture and family heirlooms, chests of silver and china, stoves, and pianos, broken wagons, and dead animals.

Most wagon trains had at least 25 wagons. Perhaps the largest wagon train to travel on the Oregon Trail left Missouri in 1843 with over 100 wagons, 1,000 men, women and children, and 5,000 head of oxen and cattle. The train was led by a Methodist missionary named Dr. Elijah White. But wagon trains became so common on the trail that processions seemed to have no beginning or end. Diaries told of hundreds of wagons passing by Fort Laramie in a single day in the 1850s. Foraging for the teams became a serious challenge because grazing near the trail had been exhausted.

Two posts from the pioneer diary of Elizabeth J. Goltra provide a glimpse of traveling on the trail:

September 20, 1853: Two of our horses are missing this morning. Bought 30 pounds of beef and some other eatables… found plenty of wood and water and grass one mile south. We are now at the foot of the Cascades, in heavy timber. Bought 80 pounds of flour off an emigrant at 10¢ per pound. We now have plenty of provisions to last us through. We guard our cattle very closely or we would lose them in the timber. Rest the remainder of the day to let the cattle eat plenty for feed is scarce in the mountains.

September 24, 1853: This is a very rainy morning. The roads are very bad. Fearful of being caught in a snowstorm… This is the roughest and steepest hill on the road. Got down all safe by cutting and chaining a tree behind the wagon 100 feet long. Camped at the foot of the hill and tied our stock up with nothing to eat but a little grass we carried along with us.

PHOTOS: (1) Conestoga wagons were used early in pioneer history to travel on the Appalachian Trail and east of the Mississippi. But they were extremely heavy—up to six tons loaded--and required up to six animals, usually oxen, to pull. (2) The smaller Prairie Schooner started to replace the larger Connestoga wagons and were often built in the Midwest near the starting point of the Oregon Trail. (3) Two families rest at the end of the day on the trail at the foothills of the Rockies in northern Utah,1870. Photograph by Henry Martinean. Denver Public Library. (4) A very rare photograph of the inside of a covered wagon packed for the Oregon Trail shows the crowded quarters. (5) Custer’s Black Hills Expedition of 1874 included 110 covered wagons, 1,200 men, artillery and food supply for two months. This expedition was about the same size as the largest wagon train ever to travel the Oregon Trail.

You may also enjoy these related posts:

-What Pioneers Ate

https://www.notesfromthefrontier.com/post/what-pioneers-ate

-Pioneer Survival Guides

https://www.notesfromthefrontier.com/post/pioneer-survival-guides-in-the-1800s

"What Pioneers Packed" was originally posted on Facebook and NotesfromtheFrontier.com on June 24, 2019

513,667 views / 23,754 likes / 14,767 shares / 676 comments

© 2021 NOTES FROM THE FRONTIER

- Homesteading Life

- Most Popular

Thank you for this wonderful and detailed post. the photos and drawings are awesome and so helpful in research.

Thank you, Gini❣️

I really enjoyed this article! I’m always fascinated with American pioneer history!!

Great article and photos. Much appreciated. Really brought out what hardships they faced and what was needed to survive them. Interesting re: food supplies.

Thanks for your question, Jim. I can’t answer your question off the top of my head, but I do know that reliable wagon masters were a rare breed and a very valuable commodity! Many had worked the fur trade or been Indian scouts. This would make an excellent post in the future! Look for it. Thanks again.

Any recollection of a Peter Purrier as a wagon master? Approximately how many “reliable” wagon masters were there. Thanks Jim Wheeler

Deborah Hufford

Author, Notes from the Frontier

Deborah Hufford is an award-winning author and magazine editor with a passion for history. Her popular NotesfromtheFrontier.com blog with 100,000+ readers has led to an upcoming novel ! Growing up as an Iowa farmgirl, rodeo queen and voracious reader, her love of land, lore and literature fired her writing muse. With a Bachelor's in English and Master's in Journalism from the University of Iowa , she taught students of Iowa's Writer's Workshop , then at Northwestern University , Marquette and Mount Mary . Her extensive publishing career began at Better Homes & Gardens , includes credits in New York Times Magazine , New York Times , Connoisseur , many other titles, and serving as publisher of The Writer's Handbook .

Deeply devoted to social justice, especially for veterans, women, and Native Americans, she has served on boards and donated her fundraising skills to Chief Joseph Foundation , Missing & Murdered Indigenous Women ( MMIW ), Homeless Veterans Initiative , Humane Society , and other nonprofits.

Deborah's soon-to-be released historical novel, BLOOD TO RUBIES weaves indigenous and pioneer history, strong women and clashing worlds into a sweeping saga praised by NYT bestselling authors as "crushing," "rhapsodic," "gritty," and "sensuous." Purchase BLOOD TO RUBIES online beginning June 9. Connect with Deborah on DeborahHufford.com , Facebook , and Instagram .

Watch CBS News

Earthquake maps show where seismic activity shook the Northeast today

By Lucia Suarez Sang

Updated on: April 5, 2024 / 7:51 PM EDT / CBS News

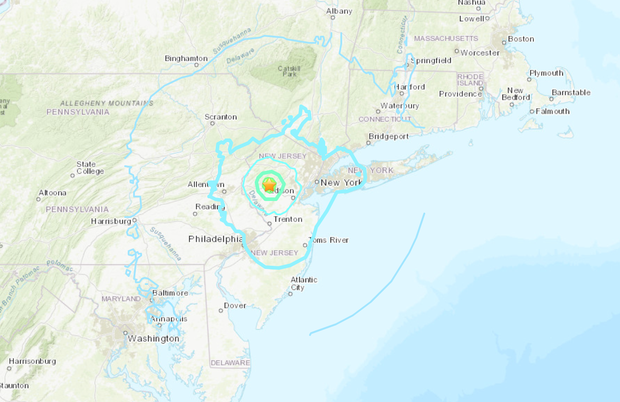

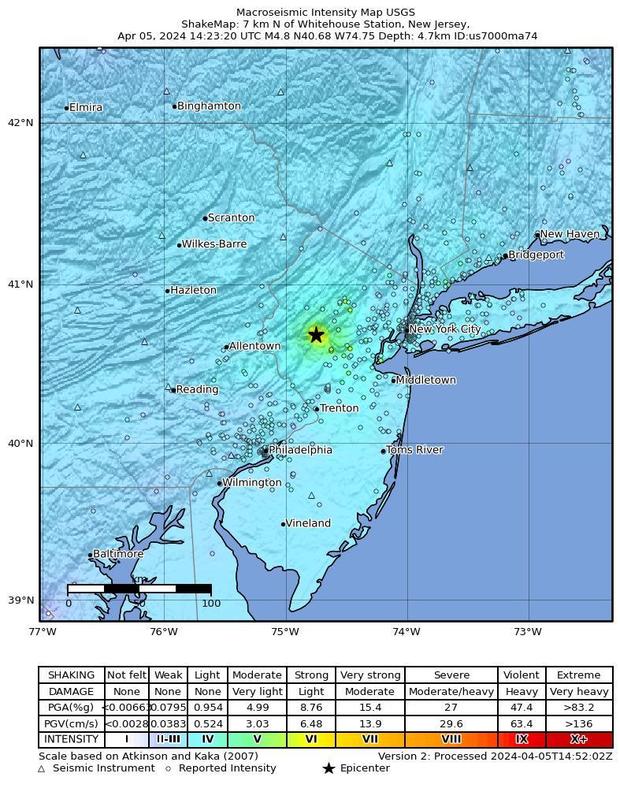

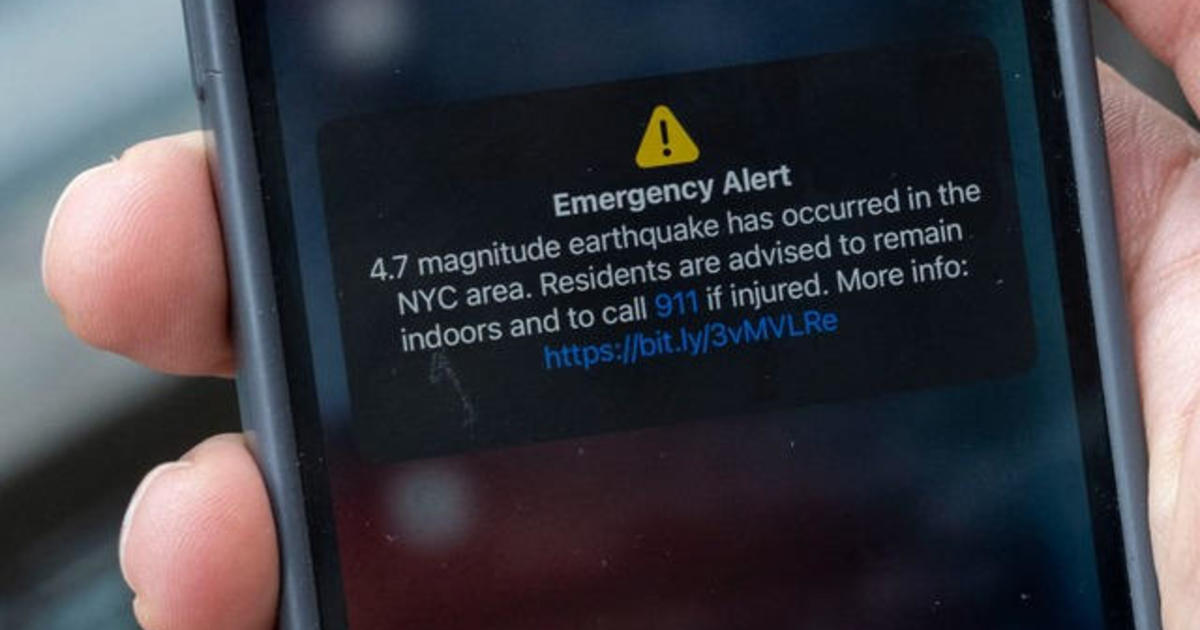

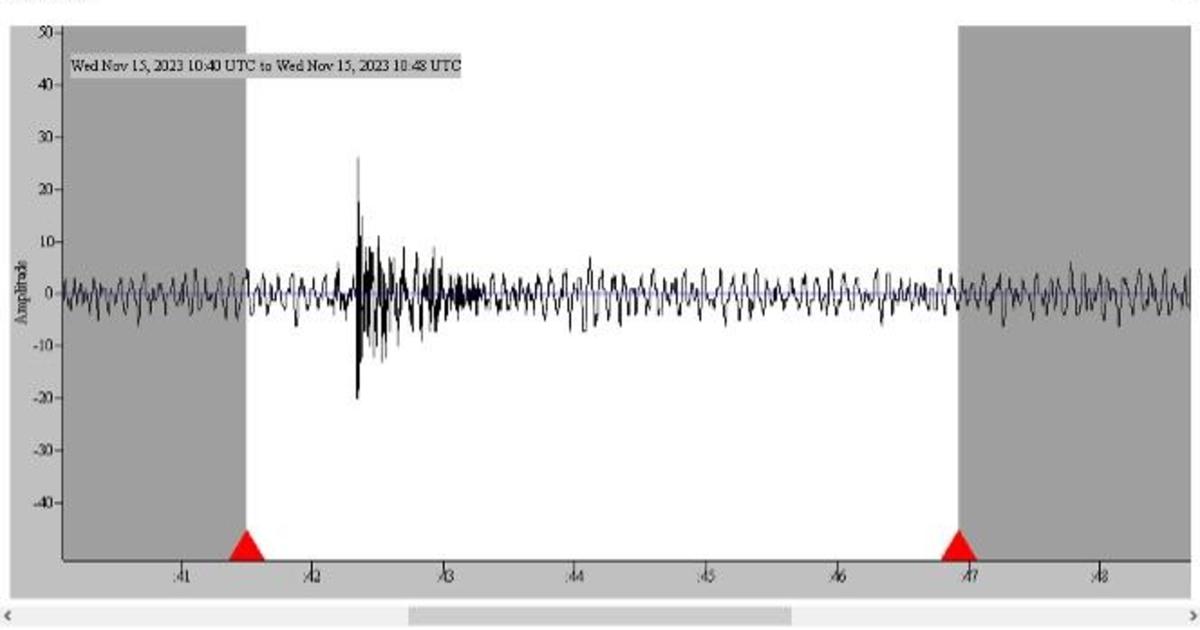

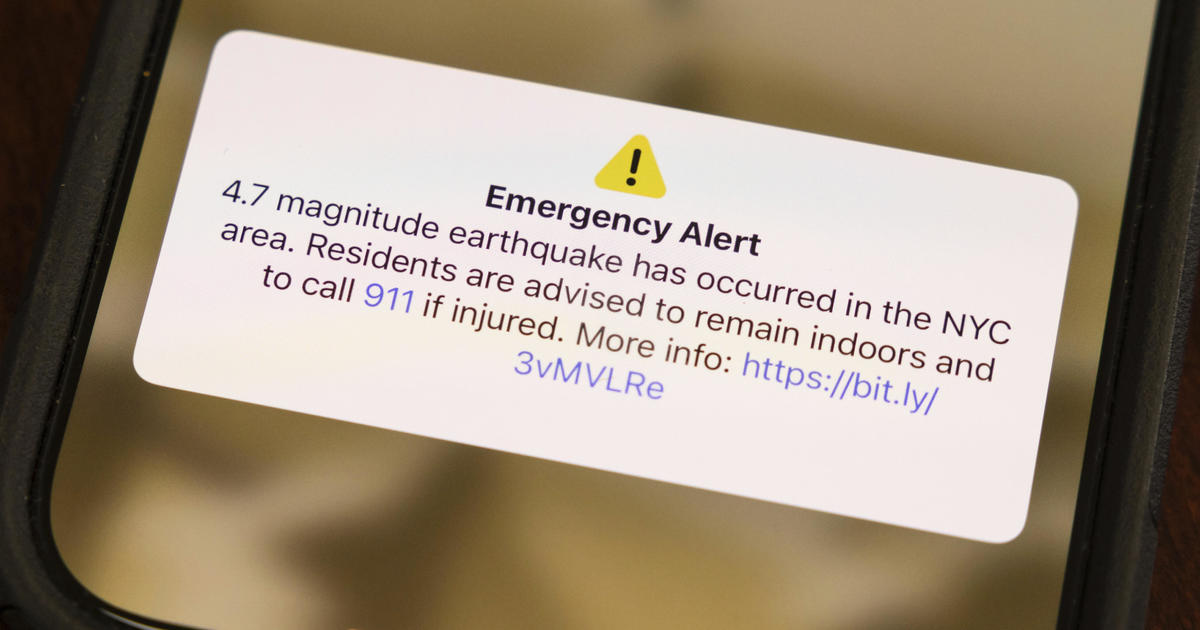

Residents across the Northeast were rattled by a 4.8 magnitude earthquake that shook the densely populated New York City metropolitan area and much of the surrounding region on Friday morning. The U.S. Geological Survey was quick to release maps showing the spot where the quake was centered, in New Jersey, and the area where it was felt.

The USGS reported the quake occurred about 7 miles north of Whitehouse Station, New Jersey. It indicated that the quake might have been felt by more than 42 million people. There were several aftershocks later in the day, including one with a magnitude of 4.0.

People in Baltimore , Philadelphia , New Jersey, Connecticut, Boston and other areas of the Northeast reported shaking. Tremors lasting for several seconds were felt over 200 miles away near the Massachusetts-New Hampshire border.

The map below shows the seismic intensity of the earthquake. The map, which is mostly a lighter shade of blue, shows that the intensity was light to weak, depending on the distance from the epicenter.

Another map released by the European-Mediterranean Seismological Centre on X, formerly Twitter, highlights the eyewitness reports of shaking and possible damage levels during the seismic event.

#Earthquake 18 mi W of #Plainfield (New Jersey) 23 min ago (local time 10:23:20). Updated map - Colored dots represent local shaking & damage level reported by eyewitnesses. Share your experience via: 📱 https://t.co/IbUfG7TFOL 🌐 https://t.co/wErQf69jIn pic.twitter.com/jBjVw1ngAD — EMSC (@LastQuake) April 5, 2024

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul and New York City Mayor Eric Adams have been briefed on the quake.

"We're taking this extremely seriously and here's why: There's always the possibility of aftershocks. We have not felt a magnitude of this earthquake since about 2011," Hochul said.

People across the region were startled by the rumbling of the quake. One New York City resident told CBS New York's Elijah Westbrook, "I was laying in my bed, and my whole apartment building started shaking. I started freaking out,"

It's not the first time the East Coast and New York City have been hit by an earthquake.

A 5.0 quake was measured in New York City in 1884.

The shaking stirred memories of the Aug. 23, 2011, earthquake that jolted tens of millions of people from Georgia to Canada. Registering magnitude 5.8, it was the strongest quake to hit the East Coast since World War II. The epicenter was in Virginia.

That earthquake left cracks in the Washington Monument, spurred the evacuation of the White House and Capitol and rattled New Yorkers three weeks before the 10th anniversary of the Sept. 11 terror attacks.

- New England

- Connecticut

- Earthquakes

- United States Geological Survey

- Philadelphia

More from CBS News

How are earthquakes measured? How today's event stacks up to past quakes

What causes earthquakes? The science behind why they happen

Earthquake snarls air and train travel in the New York City area

NYC, New Jersey earthquake witnesses share first-hand accounts

Total solar eclipse April 8, 2024 facts: Path, time and the best places to view

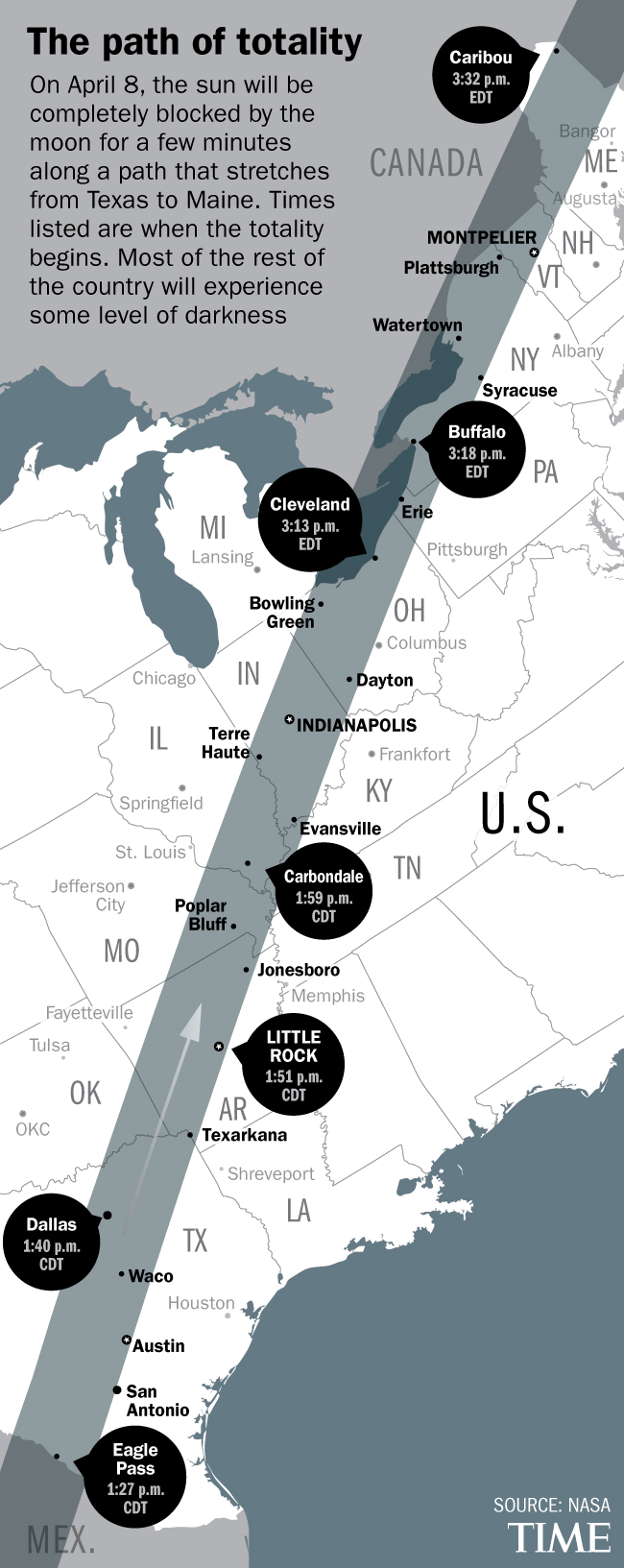

In the U.S., 31 million people already live inside the path of totality.

Scroll down to see the list of U.S. cities where the April 8 total solar eclipse will be visible, the duration of the eclipse in those locations and what time totality will begin, according to GreatAmericanEclipse.com .