- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Christopher Columbus

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 11, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The explorer Christopher Columbus made four trips across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain: in 1492, 1493, 1498 and 1502. He was determined to find a direct water route west from Europe to Asia, but he never did. Instead, he stumbled upon the Americas. Though he did not “discover” the so-called New World—millions of people already lived there—his journeys marked the beginning of centuries of exploration and colonization of North and South America.

Christopher Columbus and the Age of Discovery

During the 15th and 16th centuries, leaders of several European nations sponsored expeditions abroad in the hope that explorers would find great wealth and vast undiscovered lands. The Portuguese were the earliest participants in this “ Age of Discovery ,” also known as “ Age of Exploration .”

Starting in about 1420, small Portuguese ships known as caravels zipped along the African coast, carrying spices, gold and other goods as well as enslaved people from Asia and Africa to Europe.

Did you know? Christopher Columbus was not the first person to propose that a person could reach Asia by sailing west from Europe. In fact, scholars argue that the idea is almost as old as the idea that the Earth is round. (That is, it dates back to early Rome.)

Other European nations, particularly Spain, were eager to share in the seemingly limitless riches of the “Far East.” By the end of the 15th century, Spain’s “ Reconquista ”—the expulsion of Jews and Muslims out of the kingdom after centuries of war—was complete, and the nation turned its attention to exploration and conquest in other areas of the world.

Early Life and Nationality

Christopher Columbus, the son of a wool merchant, is believed to have been born in Genoa, Italy, in 1451. When he was still a teenager, he got a job on a merchant ship. He remained at sea until 1476, when pirates attacked his ship as it sailed north along the Portuguese coast.

The boat sank, but the young Columbus floated to shore on a scrap of wood and made his way to Lisbon, where he eventually studied mathematics, astronomy, cartography and navigation. He also began to hatch the plan that would change the world forever.

Christopher Columbus' First Voyage

At the end of the 15th century, it was nearly impossible to reach Asia from Europe by land. The route was long and arduous, and encounters with hostile armies were difficult to avoid. Portuguese explorers solved this problem by taking to the sea: They sailed south along the West African coast and around the Cape of Good Hope.

But Columbus had a different idea: Why not sail west across the Atlantic instead of around the massive African continent? The young navigator’s logic was sound, but his math was faulty. He argued (incorrectly) that the circumference of the Earth was much smaller than his contemporaries believed it was; accordingly, he believed that the journey by boat from Europe to Asia should be not only possible, but comparatively easy via an as-yet undiscovered Northwest Passage .

He presented his plan to officials in Portugal and England, but it was not until 1492 that he found a sympathetic audience: the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile .

Columbus wanted fame and fortune. Ferdinand and Isabella wanted the same, along with the opportunity to export Catholicism to lands across the globe. (Columbus, a devout Catholic, was equally enthusiastic about this possibility.)

Columbus’ contract with the Spanish rulers promised that he could keep 10 percent of whatever riches he found, along with a noble title and the governorship of any lands he should encounter.

Where Did Columbus' Ships, Niña, Pinta and Santa Maria, Land?

On August 3, 1492, Columbus and his crew set sail from Spain in three ships: the Niña , the Pinta and the Santa Maria . On October 12, the ships made landfall—not in the East Indies, as Columbus assumed, but on one of the Bahamian islands, likely San Salvador.

For months, Columbus sailed from island to island in what we now know as the Caribbean, looking for the “pearls, precious stones, gold, silver, spices, and other objects and merchandise whatsoever” that he had promised to his Spanish patrons, but he did not find much. In January 1493, leaving several dozen men behind in a makeshift settlement on Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), he left for Spain.

He kept a detailed diary during his first voyage. Christopher Columbus’s journal was written between August 3, 1492, and November 6, 1492 and mentions everything from the wildlife he encountered, like dolphins and birds, to the weather to the moods of his crew. More troublingly, it also recorded his initial impressions of the local people and his argument for why they should be enslaved.

“They… brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks’ bells," he wrote. "They willingly traded everything they owned… They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features… They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron… They would make fine servants… With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”

Columbus gifted the journal to Isabella upon his return.

Christopher Columbus's Later Voyages

About six months later, in September 1493, Columbus returned to the Americas. He found the Hispaniola settlement destroyed and left his brothers Bartolomeo and Diego Columbus behind to rebuild, along with part of his ships’ crew and hundreds of enslaved indigenous people.

Then he headed west to continue his mostly fruitless search for gold and other goods. His group now included a large number of indigenous people the Europeans had enslaved. In lieu of the material riches he had promised the Spanish monarchs, he sent some 500 enslaved people to Queen Isabella. The queen was horrified—she believed that any people Columbus “discovered” were Spanish subjects who could not be enslaved—and she promptly and sternly returned the explorer’s gift.

In May 1498, Columbus sailed west across the Atlantic for the third time. He visited Trinidad and the South American mainland before returning to the ill-fated Hispaniola settlement, where the colonists had staged a bloody revolt against the Columbus brothers’ mismanagement and brutality. Conditions were so bad that Spanish authorities had to send a new governor to take over.

Meanwhile, the native Taino population, forced to search for gold and to work on plantations, was decimated (within 60 years after Columbus landed, only a few hundred of what may have been 250,000 Taino were left on their island). Christopher Columbus was arrested and returned to Spain in chains.

In 1502, cleared of the most serious charges but stripped of his noble titles, the aging Columbus persuaded the Spanish crown to pay for one last trip across the Atlantic. This time, Columbus made it all the way to Panama—just miles from the Pacific Ocean—where he had to abandon two of his four ships after damage from storms and hostile natives. Empty-handed, the explorer returned to Spain, where he died in 1506.

Legacy of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus did not “discover” the Americas, nor was he even the first European to visit the “New World.” (Viking explorer Leif Erikson had sailed to Greenland and Newfoundland in the 11th century.)

However, his journey kicked off centuries of exploration and exploitation on the American continents. The Columbian Exchange transferred people, animals, food and disease across cultures. Old World wheat became an American food staple. African coffee and Asian sugar cane became cash crops for Latin America, while American foods like corn, tomatoes and potatoes were introduced into European diets.

Today, Columbus has a controversial legacy —he is remembered as a daring and path-breaking explorer who transformed the New World, yet his actions also unleashed changes that would eventually devastate the native populations he and his fellow explorers encountered.

HISTORY Vault: Columbus the Lost Voyage

Ten years after his 1492 voyage, Columbus, awaiting the gallows on criminal charges in a Caribbean prison, plotted a treacherous final voyage to restore his reputation.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The First New World Voyage of Christopher Columbus (1492)

European Exploration of the Americas

Spencer Arnold/Getty Images

- Ph.D., Spanish, Ohio State University

- M.A., Spanish, University of Montana

- B.A., Spanish, Penn State University

How was the first voyage of Columbus to the New World undertaken, and what was its legacy? Having convinced the King and Queen of Spain to finance his voyage, Christopher Columbus departed mainland Spain on August 3, 1492. He quickly made port in the Canary Islands for a final restocking and left there on September 6. He was in command of three ships: the Pinta, the Niña, and the Santa María. Although Columbus was in overall command, the Pinta was captained by Martín Alonso Pinzón and the Niña by Vicente Yañez Pinzón.

First Landfall: San Salvador

On October 12, Rodrigo de Triana, a sailor aboard the Pinta, first sighted land. Columbus himself later claimed that he had seen a sort of light or aura before Triana did, allowing him to keep the reward he had promised to give to whoever spotted land first. The land turned out to be a small island in the present-day Bahamas. Columbus named the island San Salvador, although he remarked in his journal that the natives referred to it as Guanahani. There is some debate over which island was Columbus’ first stop; most experts believe it to be San Salvador, Samana Cay, Plana Cays or Grand Turk Island.

Second Landfall: Cuba

Columbus explored five islands in the modern-day Bahamas before he made it to Cuba. He reached Cuba on October 28, making landfall at Bariay, a harbor near the eastern tip of the island. Thinking he had found China, he sent two men to investigate. They were Rodrigo de Jerez and Luis de Torres, a converted Jew who spoke Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic in addition to Spanish. Columbus had brought him as an interpreter. The two men failed in their mission to find the Emperor of China but did visit a native Taíno village. There they were the first to observe the smoking of tobacco, a habit which they promptly picked up.

Third Landfall: Hispaniola

Leaving Cuba, Columbus made landfall on the Island of Hispaniola on December 5. Indigenous people called it Haití but Columbus referred to it as La Española, a name which was later changed to Hispaniola when Latin texts were written about the discovery. On December 25, the Santa María ran aground and had to be abandoned. Columbus himself took over as captain of the Niña, as the Pinta had become separated from the other two ships. Negotiating with the local chieftain Guacanagari, Columbus arranged to leave 39 of his men behind in a small settlement, named La Navidad .

Return to Spain

On January 6, the Pinta arrived, and the ships were reunited: they set out for Spain on January 16. The ships arrived in Lisbon, Portugal, on March 4, returning to Spain shortly after that.

Historical Importance of Columbus' First Voyage

In retrospect, it is somewhat surprising that what is today considered one of the most important voyages in history was something of a failure at the time. Columbus had promised to find a new, quicker route to the lucrative Chinese trade markets and he failed miserably. Instead of holds full of Chinese silks and spices, he returned with some trinkets and a few bedraggled Indigenous people from Hispaniola. Some 10 more had perished on the voyage. Also, he had lost the largest of the three ships entrusted to him.

Columbus actually considered the Indigenous people his greatest find. He thought that a new trade of enslaved people could make his discoveries lucrative. Columbus was hugely disappointed a few years later when Queen Isabela, after careful thought, decided not to open the New World to the trading of enslaved people.

Columbus never believed that he had found something new. He maintained, to his dying day, that the lands he discovered were indeed part of the known Far East. In spite of the failure of the first expedition to find spices or gold, a much larger second expedition was approved, perhaps in part due to Columbus’ skills as a salesman.

Herring, Hubert. A History of Latin America From the Beginnings to the Present. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962

Thomas, Hugh. "Rivers of Gold: The Rise of the Spanish Empire, from Columbus to Magellan." 1st edition, Random House, June 1, 2004.

- Biography of Christopher Columbus

- La Navidad: First European Settlement in the Americas

- Biography of Christopher Columbus, Italian Explorer

- The Third Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- The Second Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- 10 Facts About Christopher Columbus

- The Truth About Christopher Columbus

- The Fourth Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- Biography of Juan Ponce de León, Conquistador

- Amerigo Vespucci, Explorer and Navigator

- Where Are the Remains of Christopher Columbus?

- Biography of Diego Velazquez de Cuellar, Conquistador

- The Florida Expeditions of Ponce de Leon

- A Brief History of the Age of Exploration

- Did Christopher Columbus Actually Discover America?

Account Options

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

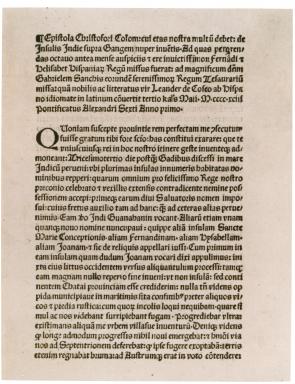

Columbus reports on his first voyage, 1493

A spotlight on a primary source by christopher columbus.

On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from Spain to find an all-water route to Asia. On October 12, more than two months later, Columbus landed on an island in the Bahamas that he called San Salvador; the natives called it Guanahani.

For nearly five months, Columbus explored the Caribbean, particularly the islands of Juana (Cuba) and Hispaniola (Santo Domingo), before returning to Spain. He left thirty-nine men to build a settlement called La Navidad in present-day Haiti. He also kidnapped several Native Americans (between ten and twenty-five) to take back to Spain—only eight survived. Columbus brought back small amounts of gold as well as native birds and plants to show the richness of the continent he believed to be Asia.

When Columbus arrived back in Spain on March 15, 1493, he immediately wrote a letter announcing his discoveries to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, who had helped finance his trip. The letter was written in Spanish and sent to Rome, where it was printed in Latin by Stephan Plannck. Plannck mistakenly left Queen Isabella’s name out of the pamphlet’s introduction but quickly realized his error and reprinted the pamphlet a few days later. The copy shown here is the second, corrected edition of the pamphlet.

The Latin printing of this letter announced the existence of the American continent throughout Europe. “I discovered many islands inhabited by numerous people. I took possession of all of them for our most fortunate King by making public proclamation and unfurling his standard, no one making any resistance,” Columbus wrote.

In addition to announcing his momentous discovery, Columbus’s letter also provides observations of the native people’s culture and lack of weapons, noting that “they are destitute of arms, which are entirely unknown to them, and for which they are not adapted; not on account of any bodily deformity, for they are well made, but because they are timid and full of terror.” Writing that the natives are “fearful and timid . . . guileless and honest,” Columbus declares that the land could easily be conquered by Spain, and the natives “might become Christians and inclined to love our King and Queen and Princes and all the people of Spain.”

An English translation of this document is available.

I have determined to write you this letter to inform you of everything that has been done and discovered in this voyage of mine.

On the thirty-third day after leaving Cadiz I came into the Indian Sea, where I discovered many islands inhabited by numerous people. I took possession of all of them for our most fortunate King by making public proclamation and unfurling his standard, no one making any resistance. The island called Juana, as well as the others in its neighborhood, is exceedingly fertile. It has numerous harbors on all sides, very safe and wide, above comparison with any I have ever seen. Through it flow many very broad and health-giving rivers; and there are in it numerous very lofty mountains. All these island are very beautiful, and of quite different shapes; easy to be traversed, and full of the greatest variety of trees reaching to the stars. . . .

In the island, which I have said before was called Hispana , there are very lofty and beautiful mountains, great farms, groves and fields, most fertile both for cultivation and for pasturage, and well adapted for constructing buildings. The convenience of the harbors in this island, and the excellence of the rivers, in volume and salubrity, surpass human belief, unless on should see them. In it the trees, pasture-lands and fruits different much from those of Juana. Besides, this Hispana abounds in various kinds of species, gold and metals. The inhabitants . . . are all, as I said before, unprovided with any sort of iron, and they are destitute of arms, which are entirely unknown to them, and for which they are not adapted; not on account of any bodily deformity, for they are well made, but because they are timid and full of terror. . . . But when they see that they are safe, and all fear is banished, they are very guileless and honest, and very liberal of all they have. No one refuses the asker anything that he possesses; on the contrary they themselves invite us to ask for it. They manifest the greatest affection towards all of us, exchanging valuable things for trifles, content with the very least thing or nothing at all. . . . I gave them many beautiful and pleasing things, which I had brought with me, for no return whatever, in order to win their affection, and that they might become Christians and inclined to love our King and Queen and Princes and all the people of Spain; and that they might be eager to search for and gather and give to us what they abound in and we greatly need.

Questions for Discussion

Read the document introduction and transcript in order to answer these questions.

- Columbus described the Natives he first encountered as “timid and full of fear.” Why did he then capture some Natives and bring them aboard his ships?

- Imagine the thoughts of the Europeans as they first saw land in the “New World.” What do you think would have been their most immediate impression? Explain your answer.

- Which of the items Columbus described would have been of most interest to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella? Why?

- Why did Columbus describe the islands and their inhabitants in great detail?

- It is said that this voyage opened the period of the “Columbian Exchange.” Why do you think that term has been attached to this period of time?

A printer-friendly version is available here .

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter..

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

- ALL OVER THE MAP

A 500-year-old map used by Columbus reveals its secrets

Newly uncovered text opens a time capsule of one of history’s most influential maps.

This 1491 map is the best surviving map of the world as Christopher Columbus knew it as he made his first voyage across the Atlantic. In fact, Columbus likely used a copy of it in planning his journey.

The map, created by the German cartographer Henricus Martellus, was originally covered with dozens of legends and bits of descriptive text, all in Latin. Most of it has faded over the centuries.

But now researchers have used modern technology to uncover much of this previously illegible text. In the process, they’ve discovered new clues about the sources Martellus used to make his map and confirmed the huge influence it had on later maps, including a famous 1507 map by Martin Waldseemuller that was the first to use the name “America.”

MARTELLUS AND COLUMBUS

Contrary to popular myth, 15th-century Europeans did not believe that Columbus would sail off the edge of a flat Earth, says Chet Van Duzer, the map scholar who led the study. But their understanding of the world was quite different from ours, and Martellus’s map reflects that.

Its depiction of Europe and the Mediterranean Sea is more or less accurate, or at least recognizable. But southern Africa is oddly shaped like a boot with its toe pointing to the east, and Asia is also twisted out of shape. The large island in the South Pacific roughly where Australia can actually be found must have been a lucky guess, Van Duzer says, as Europeans wouldn’t discover that continent for another century. Martellus filled the southern Pacific Ocean with imaginary islands, apparently sharing the common mapmakers’ aversion to empty spaces .

Another quirk of Martellus’s geography helps tie his map to Columbus’s journey: the orientation of Japan. At the time the map was created, Europeans knew Japan existed, but knew very little about its geography. Marco Polo’s journals, the best available source of information about East Asia at the time, had nothing to say about the island’s orientation.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Martellus’s map shows it running north-south. Correct, but almost certainly another lucky guess says Van Duzer, as no other known map of the time shows Japan unambiguously oriented this way. Columbus’s son Ferdinand later wrote that his father believed Japan to be oriented north-south, indicating that he very likely used Martellus’s map as a reference.

When Columbus made landfall in the West Indies on October 12, 1492, he began looking for Japan, still believing that he’d achieved his goal of finding a route to Asia. He was likely convinced Japan must be near because he’d travelled roughly the same distance that Martellus’s map suggests lay between Europe and Japan, Van Duzer argues in a new book detailing his findings.

Van Duzer says it’s reasonable to speculate that as Columbus sailed down the coast of Central and South America on later voyages, he pictured himself sailing down the coast of Asia as depicted on Martellus’s map.

You May Also Like

Gettysburg was no ordinary battle. These maps reveal how Lee lost the fight.

These enigmatic documents have kept their secrets for centuries

This European map inspired a playful cartography craze 500 years ago

Restoring a time capsule.

The map is roughly 3.5 by 6 feet. Such a large map would have been a luxury object, likely commissioned by a member of the nobility, but there’s no shield or dedication to indicate who that might have been. It was donated anonymously to Yale University in 1962 and remains in the university’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Over time, much of the text had faded to almost perfectly match the background, making it impossible to read. But in 2014 Van Duzer won a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities that allowed him and a team of collaborators to use a technique called multispectral imaging to try to uncover the hidden text.

The method involved taking many hundreds of photographs of the map with different wavelengths of light and processing the images to find the combination of wavelengths that best improves legibility on each part of the map (you can play around with an interactive map created by one of Van Duzer’s colleagues here ).

Many of the map legends describe the regions of the world and their inhabitants. “Here are found the Hippopodes: they have a human form but the feet of horses,” reads one previously illegible text over Central Asia. Another describes “monsters similar to humans whose ears are so large that they can cover their whole body.” Many of these fantastical creatures can be traced to texts written by the ancient Greeks.

The most surprising revelation, however, was in the interior of Africa, Van Duzer says. Martellus included many details and place names that appear to trace back to an Ethiopian delegation that visited Florence in 1441. Van Duzer says he knows of no other 15th-century European map that has this much information about the geography of Africa, let alone information derived from native Africans instead of European explorers. “I was blown away,” he says.

The imaging also strengthens the case that Martellus’s map was a major source for two even more famous cartographic objects: the oldest surviving terrestrial globe , created by Martin Behaim in 1492, and Martin Waldseemuller’s 1507 world map , the first to apply the label “America” to the continents of the western hemisphere. (The Library of Congress purchased Waldseemuller’s map for a record $10 million in 2003.)

Waldseemuller liberally copied text from Martellus, Van Duzer found after comparing the two maps. The practice was common in those days—in fact, Martellus himself apparently copied the sea monsters on his map from an encyclopedia published in 1491, an observation that helps date the map.

Despite their commonalities, the maps by Martellus and Waldseemuller have one glaring difference. Martellus depicts Europe and Africa nearly at the left edge of his map, with only water beyond. Waldseemuller’s map extends further to the west and depicts new lands on the other side of the Atlantic. Only 16 years had passed between the making of the two maps, but the world had changed forever.

Greg Miller and Betsy Mason are authors of the forthcoming illustrated book from National Geographic, All Over the Map . Follow the blog on Twitter and Instagram .

Related Topics

- AGE OF DISCOVERY

The lost continent of Zealandia has been mapped for the first time

Legendary Spanish galleon shipwreck discovered on Oregon coast

Vlad the Impaler's thirst for blood was an inspiration for Count Dracula

Magellan got the credit, but this man was first to sail around the world

Swastika Mountain needed a new name. Here’s how it got one.

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

The Ages of Exploration

Christopher columbus, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

He is credited for discovering the Americas in 1492, although we know today people were there long before him; his real achievement was that he opened the door for more exploration to a New World.

Name : Christopher Columbus [Kri-stə-fər] [Kə-luhm-bəs]

Birth/Death : 1451 - 1506

Nationality : Italian

Birthplace : Genoa, Italy

Christopher Columbus leaving Palos, Spain

Christopher Columbus aboard the "Santa Maria" leaving Palos, Spain on his first voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. The Mariners' Museum 1933.0746.000001

Introduction We know that In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue. But what did he actually discover? Christopher Columbus (also known as (Cristoforo Colombo [Italian]; Cristóbal Colón [Spanish]) was an Italian explorer credited with the “discovery” of the America’s. The purpose for his voyages was to find a passage to Asia by sailing west. Never actually accomplishing this mission, his explorations mostly included the Caribbean and parts of Central and South America, all of which were already inhabited by Native groups.

Biography Early Life Christopher Columbus was born in Genoa, part of present-day Italy, in 1451. His parents’ names were Dominico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa. He had three brothers: Bartholomew, Giovanni, and Giacomo; and a sister named Bianchinetta. Christopher became an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business, but he also studied mapmaking and sailing as well. He eventually left his father’s business to join the Genoese fleet and sail on the Mediterranean Sea. 1 After one of his ships wrecked off the coast of Portugal, he decided to remain there with his younger brother Bartholomew where he worked as a cartographer (mapmaker) and bookseller. Here, he married Doña Felipa Perestrello e Moniz and had two sons Diego and Fernando.

Christopher Columbus owned a copy of Marco Polo’s famous book, and it gave him a love for exploration. In the mid 15th century, Portugal was desperately trying to find a faster trade route to Asia. Exotic goods such as spices, ivory, silk, and gems were popular items of trade. However, Europeans often had to travel through the Middle East to reach Asia. At this time, Muslim nations imposed high taxes on European travels crossing through. 2 This made it both difficult and expensive to reach Asia. There were rumors from other sailors that Asia could be reached by sailing west. Hearing this, Christopher Columbus decided to try and make this revolutionary journey himself. First, he needed ships and supplies, which required money that he did not have. He went to King John of Portugal who turned him down. He then went to the rulers of England, and France. Each declined his request for funding. After seven years of trying, he was finally sponsored by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain.

Voyages Principal Voyage Columbus’ voyage departed in August of 1492 with 87 men sailing on three ships: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María. Columbus commanded the Santa María, while the Niña was led by Vicente Yanez Pinzon and the Pinta by Martin Pinzon. 3 This was the first of his four trips. He headed west from Spain across the Atlantic Ocean. On October 12 land was sighted. He gave the first island he landed on the name San Salvador, although the native population called it Guanahani. 4 Columbus believed that he was in Asia, but was actually in the Caribbean. He even proposed that the island of Cuba was a part of China. Since he thought he was in the Indies, he called the native people “Indians.” In several letters he wrote back to Spain, he described the landscape and his encounters with the natives. He continued sailing throughout the Caribbean and named many islands he encountered after his ship, king, and queen: La Isla de Santa María de Concepción, Fernandina, and Isabella.

It is hard to determine specifically which islands Columbus visited on this voyage. His descriptions of the native peoples, geography, and plant life do give us some clues though. One place we do know he stopped was in present-day Haiti. He named the island Hispaniola. Hispaniola today includes both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In January of 1493, Columbus sailed back to Europe to report what he found. Due to rough seas, he was forced to land in Portugal, an unfortunate event for Columbus. With relations between Spain and Portugal strained during this time, Ferdinand and Isabella suspected that Columbus was taking valuable information or maybe goods to Portugal, the country he had lived in for several years. Those who stood against Columbus would later use this as an argument against him. Eventually, Columbus was allowed to return to Spain bringing with him tobacco, turkey, and some new spices. He also brought with him several natives of the islands, of whom Queen Isabella grew very fond.

Subsequent Voyages Columbus took three other similar trips to this region. His second voyage in 1493 carried a large fleet with the intention of conquering the native populations and establishing colonies. At one point, the natives attacked and killed the settlers left at Fort Navidad. Over time the colonists enslaved many of the natives, sending some to Europe and using many to mine gold for the Spanish settlers in the Caribbean. The third trip was to explore more of the islands and mainland South America further. Columbus was appointed the governor of Hispaniola, but the colonists, upset with Columbus’ leadership appealed to the rulers of Spain, who sent a new governor: Francisco de Bobadilla. Columbus was taken prisoner on board a ship and sent back to Spain.

On his fourth and final journey west in 1502 Columbus’s goal was to find the “Strait of Malacca,” to try to find India. But a hurricane, then being denied entrance to Hispaniola, and then another storm made this an unfortunate trip. His ship was so badly damaged that he and his crew were stranded on Jamaica for two years until help from Hispaniola finally arrived. In 1504, Columbus and his men were taken back to Spain .

Later Years and Death Columbus reached Spain in November 1504. He was not in good health. He spent much of the last of his life writing letters to obtain the percentage of wealth overdue to be paid to him, and trying to re-attain his governorship status, but was continually denied both. Columbus died at Valladolid on May 20, 1506, due to illness and old age. Even until death, he still firmly believing that he had traveled to the eastern part of Asia.

Legacy Columbus never made it to Asia, nor did he truly discover America. His “re-discovery,” however, inspired a new era of exploration of the American continents by Europeans. Perhaps his greatest contribution was that his voyages opened an exchange of goods between Europe and the Americas both during and long after his journeys. 5 Despite modern criticism of his treatment of the native peoples there is no denying that his expeditions changed both Europe and America. Columbus day was made a federal holiday in 1971. It is recognized on the second Monday of October.

- Fergus Fleming, Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 30.

- Fleming, Off the Map, 30

- William D. Phillips and Carla Rahn Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 142-143.

- Phillips and Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus, 155.

- Robin S. Doak, Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World (Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005), 92.

Bibliography

Doak, Robin. Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World. Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005.

Fleming, Fergus. Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Phillips, William D., and Carla Rahn Phillips. The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Map of Voyages

Click below to view an example of the explorer’s voyages. Use the tabs on the left to view either 1 or multiple journeys at a time, and click on the icons to learn more about the stops, sites, and activities along the way.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

This video is part of a series of 16 animated maps.

▶ view series: the age of discovery, christopher columbus’ first voyage 1492-1493.

This map is part of a series of 16 animated maps showing the history of The Age of Discovery.

Before undertaking his first voyage, Christopher Columbus had sailed on Portuguese ships in the Atlantic Ocean along the African coast to the south and to the British Isles and perhaps Iceland to the north.

But when Lisbon refused to finance his new project, he turned to King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile and asked them to sponsor his voyage to Asia by sailing across the ocean in a westerly direction.

His flotilla of three ships set sail from Southern Spain on 3 August 1492. It headed first for the Canary Islands, where it stayed in port for a month.

Early in September, the ships set a course towards the west. After a few weeks at sea, the crew began to worry that their mission was a failure, and on 10 October they complained and threatened a mutiny, forcing Christopher Columbus to agree to turn back if no land was sighted within three days.

Two days later, on 12 October, the flotilla anchored off an inhabited island in the Bahamas. The island was given the name of San Salvador and the sailors called the inhabitants ‘Indians’, because they were convinced they had reached India.

Deciding to go further in search of gold and the continent of Asia, Columbus spent another two months sailing around in the Caribbean Sea. He discovered the islands of Juana, now Cuba, on 26 October and Hispaniola, now Santo Domingo, on 6 December.

When one of his three ships was lost after being driven onto the coast, he was forced to leave 40 men behind before turning back.

The fleet set a north-easterly course until it reached the latitude of the Azores, and then headed due east in order to take advantage of the trade winds for the trip home to Europe.

To prove that he had indeed found land, Christopher Columbus brought back a few natives, some gold and some parrots.

Three ships: These were a carrack named the Santa Maria and two caravels, the Pinta and the Nina.

HISTORIC ARTICLE

Aug 3, 1492 ce: columbus sets sail.

On August 3, 1492, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus started his voyage across the Atlantic Ocean.

Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies, U.S. History, World History

Loading ...

On August 3, 1492, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus started his voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. With a crew of 90 men and three ships—the Niña, Pinta, and Santa Maria—he left from Palos de la Frontera, Spain. Columbus reasoned that since the world is round, he could sail west to reach “the east” (the lucrative lands of India and China). That reasoning was actually sound, but the Earth is much larger than Columbus thought—large enough for him to run into two enormous continents (the “New World” of the Americas) mostly unknown to Europeans. Columbus made it to what is now the Bahamas in 61 days. He initially thought his plan was successful and the ships had reached India. In fact, he called the indigenous people “Indians,” an inaccurate name that unfortunately stuck.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

The Four Voyages of Columbus, 1492–1503

The Waldseemüller Map: Charting the New World

Two obscure 16th-century German scholars named the American continent and changed the way people thought about the world

Toby Lester

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Waldseemuller-Map-631.jpg)

It was a curious little book. When a few copies began resurfacing, in the 18th century, nobody knew what to make of it. One hundred and three pages long and written in Latin, it announced itself on its title page as follows:

INTRODUCTION TO COSMOGRAPHY WITH CERTAIN PRINCIPLES OF GEOMETRY AND ASTRONOMY NECESSARY FOR THIS MATTER

ADDITIONALLY, THE FOUR VOYAGES OF AMERIGO VESPUCCI

A DESCRIPTION OF THE WHOLE WORLD ON BOTH A GLOBE AND A FLAT SURFACE WITH THE INSERTION OF THOSE LANDS UNKNOWN TO PTOLEMY DISCOVERED BY RECENT MEN

The book—known today as the Cosmographiae Introductio , or Introduction to Cosmography —listed no author. But a printer's mark recorded that it had been published in 1507, in St. Dié, a town in eastern France some 60 miles southwest of Strasbourg, in the Vosges Mountains of Lorraine.

The word "cosmography" isn't used much today, but educated readers in 1507 knew what it meant: the study of the known world and its place in the cosmos. The author of the Introduction to Cosmography laid out the organization of the cosmos as it had been described for more than 1,000 years: the Earth sat motionless at the center, surrounded by a set of giant revolving concentric spheres. The Moon, the Sun and the planets each had their own sphere, and beyond them was the firmament, a single sphere studded with all of the stars. Each of these spheres wheeled grandly around the Earth at its own pace, in a never-ending celestial procession.

All of this was delivered in the dry manner of a textbook. But near the end, in a chapter devoted to the makeup of the Earth, the author elbowed his way onto the page and made an oddly personal announcement. It came just after he had introduced readers to Asia, Africa and Europe—the three parts of the world known to Europeans since antiquity. "These parts," he wrote, "have in fact now been more widely explored, and a fourth part has been discovered by Amerigo Vespucci (as will be heard in what follows). Since both Asia and Africa received their names from women, I do not see why anyone should rightly prevent this [new part] from being called Amerigen—the land of Amerigo, as it were—or America, after its discoverer, Americus, a man of perceptive character."

How strange. With no fanfare, near the end of a minor Latin treatise on cosmography, a nameless 16th-century author briefly stepped out of obscurity to give America its name—and then disappeared again.

Those who began studying the book soon noticed something else mysterious. In an easy-to-miss paragraph printed on the back of a foldout diagram, the author wrote, "The purpose of this little book is to write a sort of introduction to the whole world that we have depicted on a globe and on a flat surface. The globe, certainly, I have limited in size. But the map is larger."

Various remarks made in passing throughout the book implied that this map was extraordinary. It had been printed on several sheets, the author noted, suggesting that it was unusually large. It had been based on several sources: a brand-new letter by Amerigo Vespucci (included in the Introduction to Cosmography ); the work of the second-century Alexandrian geographer Claudius Ptolemy; and charts of the regions of the western Atlantic newly explored by Vespucci, Columbus and others. Most significant, it depicted the New World in a dramatically new way. "It is found," the author wrote, "to be surrounded on all sides by the ocean."

This was an astonishing statement. Histories of New World discovery have long told us that it was only in 1513—after Vasco Núñez de Balboa had first caught sight of the Pacific by looking west from a mountain peak in Panama—that Europeans began to conceive of the New World as something other than a part of Asia. And it was only after 1520, once Magellan had rounded the tip of South America and sailed into the Pacific, that Europeans were thought to have confirmed the continental nature of the New World. And yet here, in a book published in 1507, were references to a large world map that showed a new, fourth part of the world and called it America.

The references were tantalizing, but for those studying the Introduction to Cosmography in the 19th century, there was an obvious problem. The book contained no such map.

Scholars and collectors alike began to search for it, and by the 1890s, as the 400th anniversary of Columbus' first voyage approached, the search had become a quest for the cartographical Holy Grail. "No lost maps have ever been sought for so diligently as these," Britain's Geographical Journal declared at the turn of the century, referring both to the large map and the globe. But nothing turned up. In 1896, the historian of discovery John Boyd Thacher simply threw up his hands. "The mystery of the map," he wrote, "is a mystery still."

On March 4, 1493, seeking refuge from heavy seas, a storm-battered caravel flying the Spanish flag limped into Portugal's Tagus River estuary. In command was one Christoforo Colombo, a Genoese sailor destined to become better known by his Latinized name, Christopher Columbus. After finding a suitable anchorage site, Columbus dispatched a letter to his sponsors, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, reporting in exultation that after a 33-day crossing he had reached the Indies, a vast archipelago on the eastern outskirts of Asia.

The Spanish sovereigns greeted the news with excitement and pride, though neither they nor anybody else initially assumed that Columbus had done anything revolutionary. European sailors had been discovering new islands in the Atlantic for more than a century—the Canaries, the Madeiras, the Azores, the Cape Verde islands. People had good reason, based on the dazzling variety of islands that dotted the oceans of medieval maps, to assume that many more remained to be found.

Some people assumed that Columbus had found nothing more than a few new Canary Islands. Even if Columbus had reached the Indies, that didn't mean he had expanded Europe's geographical horizons. By sailing west to what appeared to be the Indies (but in actuality were the islands of the Caribbean), he had confirmed an ancient theory that nothing but a small ocean separated Europe from Asia. Columbus had closed a geographical circle, it seemed—making the world smaller, not larger.

But the world began to expand again in the early 1500s. The news first reached most Europeans in letters by Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine merchant who had taken part in at least two voyages across the Atlantic, one sponsored by Spain, the other by Portugal, and had sailed along a giant continental landmass that appeared on no maps of the time. What was sensational, even mind-blowing, about this newly discovered land was that it stretched thousands of miles beyond the Equator to the south . Printers in Florence jumped at the chance to publicize the news, and in late 1502 or early 1503 they printed a doctored version of one of Vespucci's letters, under the title Mundus Novus , or New World , in which he appeared to say that he'd discovered a new continent. The work quickly became a best seller.

"In the past," it began, "I have written to you in rather ample detail about my return from those new regions...and which can be called a new world, since our ancestors had no knowledge of them, and they are entirely new matter to those who hear about them. Indeed, it surpasses the opinion of our ancient authorities, since most of them assert that there is no continent south of the equator....[But] I have discovered a continent in those southern regions that is inhabited by more numerous peoples and animals than in our Europe, or Asia or Africa."

This passage has been described as a watershed moment in European geographical thought—the moment at which a European first became aware that the New World was distinct from Asia. But "new world" didn't necessarily mean then what it means today. Europeans used it regularly to describe any part of the known world that they had not previously visited or seen described. In fact, in another letter, unambiguously attributed to Vespucci, he made clear where he thought he had been on his voyages. "We concluded," he wrote, "that this was continental land—which I esteem to be bounded by the eastern part of Asia."

In 1504 or so, a copy of the New World letter fell into the hands of an Alsatian scholar and poet named Matthias Ringmann. Then in his early 20s, Ringmann taught school and worked as a proofreader at a small printing press in Strasbourg, but he had a side interest in classical geography—specifically, the work of Ptolemy. In a work known as the Geography , Ptolemy had explained how to map the world in degrees of latitude and longitude, a system he had used to stitch together a comprehensive picture of the world as it was known in antiquity. His maps depicted most of Europe, the northern half of Africa and the western half of Asia, but they didn't, of course, include all the parts of Asia visited by Marco Polo in the 13th century, or the parts of southern Africa discovered by the Portuguese in the latter half of the 15th century.

When Ringmann came across the New World letter, he was immersed in a careful study of Ptolemy's Geography , and he recognized that Vespucci, unlike Columbus, appeared to have sailed south right off the edge of the world that Ptolemy had mapped. Thrilled, Ringmann printed his own version of the New World letter in 1505—and to emphasize the southness of Vespucci's discovery, he changed the work's title from New World to On the Southern Shore Recently Discovered by the King of Portugal , referring to Vespucci's sponsor, King Manuel.

Not long afterward, Ringmann teamed up with a German cartographer named Martin Waldseemüller to prepare a new edition of Ptolemy's Geography . Sponsored by René II, the Duke of Lorraine, Ringmann and Waldseemüller set up shop in the little French town of St. Dié, in the mountains just southwest of Strasbourg. Working as part of a small group of humanists and printers known as the Gymnasium Vosagense, the pair developed an ambitious plan. Their edition would include not only 27 definitive maps of the ancient world, as Ptolemy had described it, but also 20 maps showing the discoveries of modern Europeans, all drawn according to the principles laid out in the Geography —a historical first.

Duke René seems to have been instrumental in inspiring this leap. From unknown contacts he had received yet another Vespucci letter, also falsified, describing his voyages and at least one nautical chart depicting the new coastlines explored to date by the Portuguese. The letter and the chart confirmed to Ringmann and Waldseemüller that Vespucci had indeed discovered a huge unknown land across the ocean to the west, in the Southern Hemisphere.

What happened next is unclear. At some time in 1505 or 1506, Ringmann and Waldseemüller decided that the land Vespucci had explored was not a part of Asia. Instead, they concluded that it must be a new, fourth part of the world.

Temporarily setting aside their work on their Ptolemy atlas, Ringmann and Waldseemüller threw themselves into the production of a grand new map that would introduce Europe to this new idea of a four-part world. The map would span 12 separate sheets, printed from carefully carved wood blocks; when pasted together, the sheets would measure a stunning 4 1/2 by 8 feet—creating one of the largest printed maps, if not the largest, ever produced to that time. In April of 1507, they began printing the map, and would later report turning out 1,000 copies.

Much of what the map showed would have come as no surprise to Europeans familiar with geography. Its depiction of Europe and North Africa derived directly from Ptolemy; sub- Saharan Africa derived from recent Portuguese nautical charts; and Asia derived from the works of Ptolemy and Marco Polo. But on the left side of the map was something altogether new. Rising out of the formerly uncharted waters of the Atlantic, stretching almost from the map's top to its bottom, was a strange new landmass, long and thin and mostly blank—and there, written across what is known today as Brazil, was a strange new name: America.

Libraries today list Martin Waldseemüller as the author of the Introduction to Cosmography , but the book does not actually single him out as such. It includes opening dedications by both him and Ringmann, but these refer to the map, not the text—and Ringmann's dedication comes first. In fact, Ringmann's fingerprints are all over the work. The book's author, for instance, demonstrates a familiarity with ancient Greek—a language that Ringmann knew well but Waldseemüller did not. The author embellishes his writing with snatches of verse by Virgil, Ovid and other classical writers—a literary tic that characterizes all of Ringmann's writing. And the one contemporary writer mentioned in the book was a friend of Ringmann's.

Ringmann the writer, Waldseemüller the mapmaker: the two men would team up in precisely this way in 1511, when Waldseemüller printed a grand map of Europe. Accompanying the map was a booklet titled Description of Europe , and in dedicating his map to Duke Antoine of Lorraine, Waldseemüller made clear who had written the book. "I humbly beg of you to accept with benevolence my work," he wrote, "with an explanatory summary prepared by Ringmann." He might just as well have been referring to the Introduction to Cosmography .

Why dwell on this arcane question of authorship? Because whoever wrote the Introduction to Cosmography was almost certainly the person who coined the name "America"—and here, too, the balance tilts in Ringmann's favor. The famous naming-of-America paragraph sounds a lot like Ringmann. He's known, for example, to have spent time mulling over the use of feminine names for concepts and places. "Why are all the virtues, the intellectual qualities and the sciences always symbolized as if they belonged to the feminine sex?" he would write in a 1511 essay. "Where does this custom spring from: a usage common not only to the pagan writers but also to the scholars of the church? It originated from the belief that knowledge is destined to be fertile of good works....Even the three parts of the old world received the name of women."

Ringmann reveals his hand in other ways. In both poetry and prose he regularly amused himself by making up words, by punning in different languages and by investing his writing with hidden meanings. The naming-of-America passage is rich in just this sort of wordplay, much of which requires a familiarity with Greek. The key to the whole passage, almost always overlooked, is the curious name Amerigen (which Ringmann quickly Latinizes and then feminizes to come up with America). To get Amerigen, Ringmann combined the name Amerigo with the Greek word gen, the accusative form of a word meaning "earth," and by doing so coined a name that means—as he himself explains—"land of Amerigo."

But the word yields other meanings. Gen can also mean "born" in Greek, and the word ameros can mean "new," making it possible to read Amerigen as not only "land of Amerigo" but also "born new"—a double-entendre that would have delighted Ringmann, and one that very nicely complements the idea of fertility that he associated with female names. The name may also contain a play on meros , a Greek word sometimes translated as "place." Here Amerigen becomes A-meri-gen, or "No-place-land"—not a bad way to describe a previously unnamed continent whose geography is still uncertain.

Copies of the Waldseemüller map began to appear at German universities in the decade after 1507; sketches of it and copies made by students and professors in Cologne, Tübingen, Leipzig and Vienna survive. The map clearly was getting around, as was the Introduction to Cosmography itself. The little book was reprinted several times and attracted acclaim across Europe, largely because of the long Vespucci letter.

What about Vespucci himself? Did he ever come across the map or the Introduction to Cosmography ? Did he ever learn that the New World had been named in his honor? The odds are that he did not. Neither the book nor the name is known to have made it to the Iberian Peninsula before he died, in Seville, in 1512. But both surfaced there soon afterward: the name America first appeared in Spain in a book printed in 1520, and Christopher Columbus' son Ferdinand, who lived in Spain, acquired a copy of the Introduction to Cosmography sometime before 1539. The Spanish didn't like the name, however. Believing that Vespucci had somehow named the New World after himself, usurping Columbus' rightful glory, they refused to put the name America on official maps and documents for two more centuries. But their cause was lost from the start. The name America, such a natural poetic counterpart to Asia, Africa and Europa, had filled a vacuum, and there was no going back, especially not after the young Gerardus Mercator, destined to become the century's most influential cartographer, decided that the whole of the New World, not just its southern part, should be so labeled. The two names he put on his 1538 world map are the ones we've used ever since: North America and South America.

Ringmann didn't have long to live after finishing the Introduction to Cosmography . By 1509 he was suffering from chest pains and exhaustion, probably from tuberculosis, and by the fall of 1511, not yet 30, he was dead. After Ringmann's death Waldseemüller continued to make maps, including at least three that depicted the New World, but never again did he depict it as surrounded by water, or call it America—more evidence that these ideas were Ringmann's. On one of his later maps, the Carta Marina of 1516—which identifies South America only as "Terra Nova"—Waldseemüller even issued a cryptic apology that seems to refer to his great 1507 map: "We will seem to you, reader, previously to have diligently presented and shown a representation of the world that was filled with error, wonder, and confusion.... As we have lately come to understand, our previous representation pleased very few people. Therefore, since true seekers of knowledge rarely color their words in confusing rhetoric, and do not embellish facts with charm but instead with a venerable abundance of simplicity, we must say that we cover our heads with a humble hood."

Waldseemüller produced no other maps after the Carta Marina, and some four years later, on March 16, 1520, in his mid-40s, he died—"dead without a will," a clerk would later write when recording the sale of his house in St. Dié.

During the decades that followed, copies of the 1507 map wore out or were discarded in favor of more up-to-date and better-printed maps, and by 1570 the map had all but vanished. One copy did survive, however. Sometime between 1515 and 1517, the Nuremberg mathematician and geographer Johannes Schöner acquired a copy and bound it into a beechwood-covered folio that he kept in his reference library. Between 1515 and 1520, Schöner studied the map carefully, but by the time he died, in 1545, he probably had not opened it in years. The map had begun its long sleep, which would last more than 350 years.

It was found again by accident, as happens so often with lost treasures. In the summer of 1901, freed from his teaching duties at Stella Matutina, a Jesuit boarding school in Feldkirch, Austria, Father Joseph Fischer set out for Germany. Balding, bespectacled and 44 years old, Fischer was a professor of history and geography. For seven years he had been haunting the public and private libraries of Europe in his spare time, hoping to find maps that showed evidence of the early Atlantic voyages of the Norsemen. This current trip was no exception. Earlier in the year, Fischer had received word that the impressive collection of maps and books at Wolfegg Castle, in southern Germany, included a rare 15th-century map that depicted Greenland in an unusual way. He had to travel only some 50 miles to reach Wolfegg, a tiny town in the rolling countryside just north of Austria and Switzerland, not far from Lake Constance. He reached the town on July 15, and upon his arrival at the castle, he would later recall, he was offered "a most friendly welcome and all the assistance that could be desired."

The map of Greenland turned out to be everything Fischer had hoped. As was his custom on research trips, after studying the map Fischer began a systematic search of the castle's entire collection. For two days he made his way through the inventory of maps and prints and spent hours immersed in the castle's rare books. And then, on July 17, his third day there, he walked over to the castle's south tower, where he had been told he would find a small second-floor garret containing what little he hadn't yet seen of the castle's collection.

The garret is a simple room. It's designed for storage, not show. Bookshelves line three of its walls from floor to ceiling, and two windows let in a cheery amount of sunlight. Wandering about the room and peering at the spines of the books on the shelves, Fischer soon came across a large folio with beechwood covers, bound together with finely tooled pigskin. Two Gothic brass clasps held the folio shut, and Fischer gently pried them open. On the inside cover he found a small bookplate, bearing the date 1515 and the name of the folio's original owner: Johannes Schöner. "Posterity," the inscription began, "Schöner gives this to you as an offering."

Fischer started leafing through the folio. To his amazement, he discovered that it contained not only a rare 1515 star chart engraved by the German artist Albrecht Dürer, but also two giant world maps. Fischer had never seen anything quite like them. In pristine condition, printed from intricately carved wood blocks, each one was made up of separate sheets that, if removed from the folio and assembled, would create maps approximately 4 1/2 by 8 feet in size.

Fischer began examining the first map in the folio. Its title, running in block letters across the bottom of the map, read, THE WHOLE WORLD ACCORDING TO THE TRADITION OF PTOLEMY AND THE VOYAGES OF AMERIGO VESPUCCI AND OTHERS. This language brought to mind the Introduction to Cosmography , a work Fischer knew well, as did the portraits of Ptolemy and Vespucci that he saw at the top of the map.

Could this be... the map? Fischer began to study it sheet by sheet. Its two center sheets, which showed Europe, northern Africa, the Middle East and western Asia, came straight from Ptolemy. Farther to the east, it presented the Far East as described by Marco Polo. Southern Africa reflected the nautical charts of the Portuguese.

It was an unusual mix of styles and sources: precisely the sort of synthesis, Fischer realized, that the Introduction to Cosmography had promised. But he began to get truly excited when he turned to the map's three western sheets. There, rising out of the sea and stretching from the top to bottom, was the New World, surrounded by water.

A legend at the bottom of the page corresponded verbatim to a paragraph in the Introduction to Cosmography . North America appeared on the top sheet, a runt version of its modern self. Just to the south lay a number of Caribbean islands, among them two big ones identified as Spagnolla and Isabella. A small legend read, "These islands were discovered by Columbus, an admiral of Genoa, at the command of the King of Spain." Moreover, the vast southern landmass stretching from above the Equator to the bottom of the map was labeled DISTANT UNKNOWN LAND. Another legend read THIS WHOLE REGION WAS DISCOVERED BY THE ORDER OF THE KING OF CASTILE. But what must have brought Fischer's heart to his mouth was what he saw on the bottom sheet: AMERICA.

The 1507 map! It had to be. Alone in the little garret in the tower of Wolfegg Castle, Father Fischer realized that he had discovered the most sought-after map of all time.

Fischer took the news of his discovery straight to his mentor, the renowned Innsbruck geographer Franz Ritter von Wieser. In the fall of 1901, after intense study, the two went public. The reception was ecstatic. "Geographical students in all parts of the world have awaited with the deepest interest details of this most important discovery," the Geographical Journal declared, breaking the news in a February 1902 essay, "but no one was probably prepared for the gigantic cartographical monster which Prof. Fischer has now awakened from so many centuries of peaceful slumber." On March 2 the New York Times followed suit: "There has lately been made in Europe one of the most remarkable discoveries in the history of cartography," its report read.

Interest in the map grew. In 1907, the London-based bookseller Henry Newton Stevens Jr., a leading dealer in Americana, secured the rights to put the 1507 map up for sale during its 400th-anniversary year. Stevens offered it as a package with the other large Waldseemüller map—the Carta Marina of 1516, which had also been bound into Schöner's folio—for $300,000, or about $7 million in today's currency. But he found no takers. The 400th anniversary passed, two world wars and the cold war engulfed Europe, and the Waldseemüller map, left alone in its tower garret, went to sleep for another century.

Today, at last, the map is awake again—this time, it would appear, for good. In 2003, after years of negotiation with the owners of Wolfegg Castle and the German government, the Library of Congress acquired it for $10 million. On April 30, 2007, almost exactly 500 years after its making, German Chancellor Angela Merkel officially transferred the map to the United States. That December, the Library of Congress put it on permanent display in its grand Jefferson Building, where it is the centerpiece of an exhibit titled "Exploring the Early Americas."

As you move through it, you pass a variety of priceless cultural artifacts made in the pre-Columbian Americas, and a choice selection of original texts and maps dating from the period of first contact between the New World and the Old. Finally you arrive at an inner sanctum, and there, reunited with the Introduction to Cosmography , the Carta Marina and a few other select geographical treasures, is the Waldseemüller map. The room is quiet, the lighting dim. To study the map you have to move close and peer carefully through the glass—and when you do, it begins to tell its stories.

Adapted from The Fourth Part of the World , by Toby Lester. © 2009 Toby Lester. Published by the Free Press. Reproduced with permission.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

The First Voyage of Columbus

Christopher Columbus departed on his first voyage from the port of Palos (near Huelva) in southern Spain, on August 3, 1492, in command of three ships : the Ni�a , the Pinta and the Santa Maria . His crew mostly came from surrounding towns such as Lepe and Moguer.

Columbus called first at the Canary Islands, the westernmost Spanish possessions. He was delayed there for four weeks by calm winds and the need for repair and refit. Columbus left the island of Gomera on September 6, 1492, but calms again left him within sight of the western island of Hierro until September 8.

Columbus went ashore the next morning at an island he called San Salvador, which the natives called Guanahani. The identity of his landfall island is in dispute, but it was most likely one of the Plana Cays in the Bahamas. At Guanahani, Columbus met and traded with the Native Americans of the Lucayan tribe. He also kidnapped several of the natives to act as guides before leaving two days later. He stopped at three other islands in the Bahamas over the next two weeks, which he named Santa Maria de la Concepci�n , Fernandina , and Isabela . These are most likely the Crooked-Acklins group, Long Island, and Fortune Island, respectively. His final stop in the Bahamas was at the Ragged Islands, which he called the Islas de Arena (Sand Islands). Following the directions of his native guides, he arrived at Bariay Bay, Cuba on October 28.

Columbus spent fruitless weeks in Cuba searching for gold, or for the Chinese civilization he had read about from Marco Polo. He reached as far west as Cayo Cruz on October 31 before north winds and increasing frustration caused a change of plan. His kidnapped Native American guides had indicated that gold was to be found on another island to the east, so Columbus reversed course. While sailing north of Cuba on November 22, Mart�n Alonso Pinz�n, captain of the Pinta , left the other two ships without permission and sailed on his own in search of an island called "Babeque" or "Baneque", where he had been told by his native guides that there was much gold. Columbus continued his exploration of Cuba with the remaining two ships, rounding the eastern end and reaching as far as Punta Guayacanes before he arrived at Hispaniola on December 5.

On Christmas Eve, the flagship Santa Maria grounded on a reef near Cap Haitien and sank the next day. Columbus used the remains of the ship to build a fort on shore, which he named La Navidad (Christmas). But the tiny Ni�a could not hold all of the remaining crew, so Columbus was forced to leave about 40 men behind to await his return from Spain. He departed from La Navidad in the Ni�a on January 2, 1493.

Now down to just one ship, Columbus continued eastward along the coast of Hispaniola, and was surprised when he came upon the Pinta on January 6. Columbus's anger at Pinz�n was eased by his relief at having another ship for his return to Spain, and by the fact that Pinz�n had finally found the long-sought gold nuggets in the bed of a local river.

The two ships departed Hispaniola from Samana Bay (in the modern Dominican Republic) on January 16, but were again separated by a fierce storm in the North Atlantic on February 14; Columbus and Pinz�n each believed that the other had perished. Columbus sighted the island of Santa Maria in the Azores the next day. After a run-in with the local governor, he arrived at Lisbon on March 4, and finally made it back to his home port of Palos on March 15, 1493.

Meanwhile, Pinz�n and the Pinta had missed the Azores and arrived at the port of Bayona in northern Spain. After a stop to repair the damaged ship, the Pinta limped into Palos just hours after the Ni�a . Pinz�n had expected to be proclaimed a hero, but the honor had already been given to Columbus. Pinz�n died a few days later.

A summary of Columbus's log of the voyage can be found here.

Christopher Columbus

Italian explorer Christopher Columbus discovered the “New World” of the Americas on an expedition sponsored by King Ferdinand of Spain in 1492.

c. 1451-1506

Quick Facts

Where was columbus born, first voyages, columbus’ 1492 route and ships, where did columbus land in 1492, later voyages across the atlantic, how did columbus die, santa maria discovery claim, columbian exchange: a complex legacy, columbus day: an evolving holiday, who was christopher columbus.

Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer and navigator. In 1492, he sailed across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain in the Santa Maria , with the Pinta and the Niña ships alongside, hoping to find a new route to Asia. Instead, he and his crew landed on an island in present-day Bahamas—claiming it for Spain and mistakenly “discovering” the Americas. Between 1493 and 1504, he made three more voyages to the Caribbean and South America, believing until his death that he had found a shorter route to Asia. Columbus has been credited—and blamed—for opening up the Americas to European colonization.

FULL NAME: Cristoforo Colombo BORN: c. 1451 DIED: May 20, 1506 BIRTHPLACE: Genoa, Italy SPOUSE: Filipa Perestrelo (c. 1479-1484) CHILDREN: Diego and Fernando

Christopher Columbus, whose real name was Cristoforo Colombo, was born in 1451 in the Republic of Genoa, part of what is now Italy. He is believed to have been the son of Dominico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa and had four siblings: brothers Bartholomew, Giovanni, and Giacomo, and a sister named Bianchinetta. He was an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business and studied sailing and mapmaking.

In his 20s, Columbus moved to Lisbon, Portugal, and later resettled in Spain, which remained his home base for the duration of his life.

Columbus first went to sea as a teenager, participating in several trading voyages in the Mediterranean and Aegean seas. One such voyage, to the island of Khios, in modern-day Greece, brought him the closest he would ever come to Asia.

His first voyage into the Atlantic Ocean in 1476 nearly cost him his life, as the commercial fleet he was sailing with was attacked by French privateers off the coast of Portugal. His ship was burned, and Columbus had to swim to the Portuguese shore.

He made his way to Lisbon, where he eventually settled and married Filipa Perestrelo. The couple had one son, Diego, around 1480. His wife died when Diego was a young boy, and Columbus moved to Spain. He had a second son, Fernando, who was born out of wedlock in 1488 with Beatriz Enriquez de Arana.

After participating in several other expeditions to Africa, Columbus learned about the Atlantic currents that flow east and west from the Canary Islands.

The Asian islands near China and India were fabled for their spices and gold, making them an attractive destination for Europeans—but Muslim domination of the trade routes through the Middle East made travel eastward difficult.

Columbus devised a route to sail west across the Atlantic to reach Asia, believing it would be quicker and safer. He estimated the earth to be a sphere and the distance between the Canary Islands and Japan to be about 2,300 miles.

Many of Columbus’ contemporary nautical experts disagreed. They adhered to the (now known to be accurate) second-century BCE estimate of the Earth’s circumference at 25,000 miles, which made the actual distance between the Canary Islands and Japan about 12,200 statute miles. Despite their disagreement with Columbus on matters of distance, they concurred that a westward voyage from Europe would be an uninterrupted water route.

Columbus proposed a three-ship voyage of discovery across the Atlantic first to the Portuguese king, then to Genoa, and finally to Venice. He was rejected each time. In 1486, he went to the Spanish monarchy of Queen Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. Their focus was on a war with the Muslims, and their nautical experts were skeptical, so they initially rejected Columbus.

The idea, however, must have intrigued the monarchs, because they kept Columbus on a retainer. Columbus continued to lobby the royal court, and soon, the Spanish army captured the last Muslim stronghold in Granada in January 1492. Shortly thereafter, the monarchs agreed to finance his expedition.

In late August 1492, Columbus left Spain from the port of Palos de la Frontera. He was sailing with three ships: Columbus in the larger Santa Maria (a type of ship known as a carrack), with the Pinta and the Niña (both Portuguese-style caravels) alongside.

On October 12, 1492, after 36 days of sailing westward across the Atlantic, Columbus and several crewmen set foot on an island in present-day Bahamas, claiming it for Spain.

There, his crew encountered a timid but friendly group of natives who were open to trade with the sailors. They exchanged glass beads, cotton balls, parrots, and spears. The Europeans also noticed bits of gold the natives wore for adornment.