- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Green Global Travel

World's largest independently owned Ecotourism / Green Travel / Sustainable Travel / Animal & Wildlife Conservation site. We share transformative Responsible Travel, Sustainable Living & Going Green Tips that make a positive impact.

The Effects of Mass Tourism (How Overtourism is Destroying 30+ Destinations)

Disclaimer: This post may contain affiliate links. All hosted affiliate links follow our editorial policies .

Mass Tourism was arguably the most significant travel trend of 2017. Its downside, “overtourism”– the point at which the needs of tourism become unsustainable for a given destination– made headlines all across the world.

“Overtourism plagues great destinations,” claimed sustainable travel expert Jonathan Tourtellot in National Geographic . “Mass Tourism is at a tipping point- but we’re all part of the problem,” wrote Martin Kettle in The Guardian .

In an Associated Press piece on “The Curse of Overtourism,” Pan Pylas examined how European destinations such as Barcelona, Dubrovnik, and Venice are struggling to deal with the negative impacts of tourism.

Here, we’ll examine what mass tourism is, why it’s so popular, and how it is negatively impacting local communities in some of the world’s most beloved travel destinations.

THE DEFINITION OF MASS TOURISM

Mass tourism was originally developed in the late 1800s in the UK by Thomas Cook, who pioneered the concept of affordable group travel tours. By establishing relationships between tour operators, transportation companies, and hotels, Cook was able to get deep volume discounts on travel services and pass those savings along to its customers.

- In modern times, the phrase often refers to budget-friendly package tours, cheap flights, all-inclusive resorts, and cruises. In general, it allows vast numbers of travelers to descend on a given destination in a relatively short time, usually during peak season.

- On the positive side, this extreme influx of tourists can help to generate jobs, stimulate the economy, and develop much-needed infrastructure.

- On the downside, many of these jobs are not given to locals, much of the revenue is kept by outside investors, and the overwhelming tourist crowds often keep locals from being able to enjoy the infrastructure benefits.

- It is inarguably the most popular form of tourism. But most responsible travel experts consider it a shallow, exploitative, and unsustainable form of travel , consuming huge amounts of resources while giving little back to the local community.

To understand why, let’s take a look at how overtourism is affecting 30+ different destinations all around the world.

THE NEGATIVE IMPACTS OF OVERTOURISM

Tourism in Africa Tourism in Asia Tourism in Australia Tourism in Europe Tourism in Central/South America Tourism in North America

TOURISM IN AFRICA

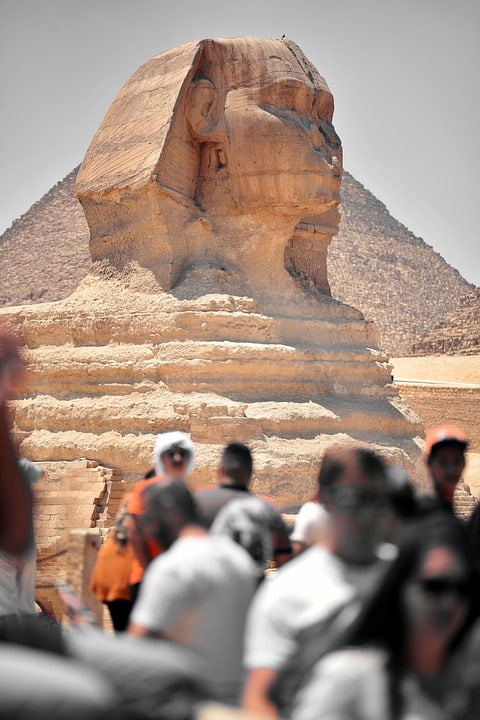

CAIRO/GIZA (Egypt)

The Cairo area is home to some of the oldest, most impressive tourist attractions in the world, from King Tut’s famous burial mask at the Egyptian Museum to the great Pyramids of Giza.

But instead of being a welcoming city that invites travelers to explore the culture and wonder of this ancient capital, mass tourism has largely taken over Cairo and Giza.

As a result, these relatively small sites have been inundated with hordes of camera-wielding tour groups stopping by on day trips from their resorts in Sharm El Sheik.

When I visited Cairo a few years ago, dozens of air-conditioned tour buses swarmed around the Giza plateau, the museum, and tourist hotspots like Khan El Khalili every single day.

They congested the roads around these attractions even more than usual, attracting exploitative cottage industries such as touts, papyrus factory tours, and unethical camel rides. The result has created a massive work and monetary imbalance in the city.

More recently, the tourism industry in and around Cairo has suffered a massive blow. Overblown safety warnings and fears have caused the local economy to crash. As Egyptian tourism starts to recover, Cairo and Giza should take a step back and learn from their past mistakes.

This is their chance to embrace responsible tourism, controlling visitor numbers and encouraging travelers to explore the ancient history and culture of the whole area, not just a few tourist hotspots. –Mike Huxley of Bemused Backpacker

MARRAKECH (Morocco)

Just 10 years ago Marrakech was a city of around 500,000 people. Today that number sits above 1.2 million. In 2008, less than 3 million tourists visited the entire country of Morocco. Last year that number was nearly 11 million, and a vast majority of them traveled to/through Marrakech.

This huge surge in the numbers of tourists and residents has done two things to my home city. First, it’s brought many jobs and much-needed income. Second, it’s put a strain on resources and infrastructure in a way that has proven difficult to manage.

Many longtime Marrakech residents felt an initial benefit from this influx of tourism when they were able to sell their properties and get work. But today the cost of basic goods, rents, and more rises while salaries remain relatively stagnant.

Tourists expect Marrakech to be a cheap destination, thanks to the subsidized low-cost carriers that fly into the city daily. This has a trickle-down effect on the economy. People need to earn more money now than they did a few years ago to maintain even a basic standard of life.

A walk through the medina today is met by hundreds, if not thousands of tourists. It’s very difficult now to experience what traditional life is like in Marrakech, primarily because residents are increasingly outnumbered by tourists.

Many visitors don’t see the negative social impacts of tourism, because Marrakech is still “much more exotic” than their home countries. But for Marrakech, tourism has proven both a blessing and a curse. – Amanda Ponzio-Mouttaki of MarocMama

Mauritius is a beautiful island in the Indian Ocean, 1,200 miles off the southeast coast of Africa . There, misty clouds linger around the top of forested mountains. Tropical temperatures allow lazy days at white sandy beaches , or snorkeling in turquoise lagoons amongst colorful fish and corals.

We stayed in Mauritius for more than a month and liked it. But the negative impacts of tourism on the island are readily apparent.

With around 1.3 million residents in 790 square miles, Mauritius is among the countries with the highest population density in the world. More than one million tourists visit Mauritius every year.

Driving across the island, it feels like one massive, congested town, with the exception of a few sugarcane fields and coastal areas dominated by luxury resorts.

Outside of southern Mauritius, where the last pocket of extended forest remains in the Black Forest National Park, very little natural habitat is left for local wildlife. Unfortunately, this is one of the island’s most heavily promoted regions for day trips, with busloads of tourists visiting every day.

It will take smarter decisions by the government, tour operators, and responsible tourism NGOs to reduce the destructive environmental impacts of tourism in Mauritius’ future. –Marcelle Heller of The Wild Life

CAPE TOWN (South Africa)

Cape Town has emerged as one on southern Africa’s favorite holiday hotspots. Despite its current problems with drought and crime, the city is still magnificent if you love the beach, ecotourism (including penguins! ) , food, and wine.

One of the major downfalls of overtourism in Cape Town is the pricing increase for property, which is creating a greater divide between rich and poor. Tourists arrive, instantly fall in love with the city, and realize property is relatively cheap.

So they decide to purchase a house or apartment, which drives up prices and makes it almost impossible for locals to afford homes. Even worse are the overseas investors who buy a property just to rent it out on Airbnb.

Other negative effects of tourism include horrendous traffic, an increase in petty theft, and the rise of begging street kids. Word to the wise: Do not come in December or January! You’ll feel suffocated, as holiday-makers descend on the city from Johannesburg and all around the world. – Callan Wienburg of Singapore n Beyond

TOURISM IN ASIA

AGRA/TAJ MAHAL (India)

Close your eyes and think of India . If anything resembling a white marble onion dome comes to mind, you’re not alone. The Taj Mahal , a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is the veritable symbol of India, and on many people’s bucket lists.

When visitors make the journey to Agra (home of the Taj Mahal) three things stand out. One, the sublime beauty of the world’s most perfect building. It is truly spectacular, and rarely disappoints. Two, the overwhelming crowds.

The Taj Mahal attracts 7 to 8 million people per year. Unless you arrive by 6 am, just before it opens, you’ll be met with hordes of people. Three, the degradation and disorder of Agra.

You’d think the city that houses one of the world’s top tourist attractions would benefit from the influx of tourism revenue. But nothing could be further from the truth.

Aside from the stringent management and upkeep of the Taj Mahal itself— which includes a pollution-free perimeter zone and a regular mudpack to clean the surface — there are almost no other signs of civic improvement in Agra. The Taj Mahal is worth seeing, no question. But there’s no denying that it is falling victim to pollution.

It’s unfortunate that the lack of marketing innovation by the Indian tourism industry results in most tourists heading straight for the “Golden Triangle” of Delhi, Agra, and Jaipur. There’s so much more to see and experience in India, far away from the crowds, touts, and other aggravations of this over-touristed route. –Mariellen Ward of Breathedreamgo

BAGAN (Myanmar)

Although mainstream tourism is relatively new in Myanmar, Bagan’s famous Valley of Temples is already suffering growing pains. Over 4,000 pagodas once stood here, but that number has been reduced by half over time by earthquakes, natural erosion, and disrespectful travelers.

One of the most common activities in Bagan is to climb the pagodas at sunrise to watch the hot air balloons glide across the sky, and again in the evening to see the sunset. The experience is extraordinary… if you can find a secluded, secure temple. However, the majority of tourists flock to the five most popular pagodas, where climbing is allowed.

The problem is that some disrespectful tourists aren’t satisfied with the views from the platform area. So they climb up the ancient brick formations to the tip of the pagodas, which often crumble. It’s an insult to the historic importance of the site. Several travelers have lost their lives after plummeting from the top.

As travelers, it is our duty to preserve these sacred cultural heritage sites. Yet repeatedly visitors destroy the places they’re so eager to cross off their bucket list, without giving any thought to future generations. – Lola Méndez of Miss Filatelista

BALI (Indonesia)

Bali used to be a peaceful place where travelers would go to escape the stress of their everyday life. They could enjoy lush nature, bask in the sun on beautifully pristine beaches, and surf some killer waves. Most visitors would spend their time immersing themselves in the ancient traditions and rituals of the local people.

This aspect of Bali is so distant now, it takes a great deal of effort to discover it. Nowadays Bali is mayhem. Due to uncontrolled development, the land that nature ruled has been filled with large chain hotels and shopping malls. Depansar, Bali’s capital, is completely congested with traffic and pollution. What used to be a tropical paradise is being ruined by overtourism.

Most of the beaches are incredibly crowded. The lack of proper garbage disposal and recycling initiatives means that places such as Kuta Beach are enormous dumps where rats party day and night . In order to accommodate the needs of mass tourism , development is slowly but steadily pushing its way through the rest of the island, too.

Visitors who wish to avoid the crowds need to travel to the north of the island and visit the most remote beaches. Renting a motorbike or a car may also be a good idea in order to travel more independently. –Claudia Tavani of My Adventures Across the World

EL NIDO, PALAWAN (Philippines)

In 2016 Palawan was named the world’s most beautiful island by Condé Nast Traveler. Known as a haven for adventurers looking to experience untouched nature, quiet turquoise waters, and respite from hordes of sun seekers, this promising ecotourism destination has exploded in popularity. Unfortunately El Nido (once a sleepy fishing village) has been bearing the brunt of it, attracting over 200,000 visitors to an area with a population of 36,000.

The problems caused by overtourism here are many. There’s rampant tourism development all over town. There’s not enough local food to feed all the visiting mouths, a problem exacerbated by the mass conversion of farmland into resort construction sites. There’s no waste water management system, meaning sewage from these newly constructed hotels goes straight into that turquoise ocean.

Island-hopping is the main attraction in El Nido’s archipelago, and every travel agency in town basically sells the same day tour. So idyllic lagoons became swamped with beer-swilling sunbathers.

Thankfully, 2017 saw the introduction of daily visitor caps to three of the main hotspots. But as long as overall visitor numbers remain unmanaged, tour operators will simply shift crowds to other islands.

So how can we visit Palawan responsibly? Steer completely clear of El Nido, at least until the powers-that-be have invested in proper infrastructure and resources to cope with tourism volume. There are plenty of beautiful spots all over the large island of Palawan, including some commendable eco-resorts in Coron. -Ellie Cleary of Soul Travel Blog

READ MORE: The Best Things To Do In Coron, Palawan Philippines

HALONG BAY (Vietnam)

As a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Halong Bay is easily the most famous site in Vietnam. It’s also the most visited, with nearly three million tourists cruising its waters every year. Hundreds of junk boats ply its water each day, against the natural backdrop of dark green rock formations shrouded in mist.

Sadly, overtourism in Halong Bay has resulted in both environmental issues and fatal accidents. The influx of visitors coupled with a lack of safety regulations has created a market saturated with irresponsible tour operators who are more concerned with profits than environmental and safety issues. In 2011, a boat sank there, killing 12 tourists. According to several comments from travelers on Lonely Planet, this isn’t an isolated incident .

We cruised Halong Bay on a mid-range overnight boat trip and it opened my eyes to what poorly managed tourism can do to a place. The beauty of the poetic landscapes is undeniable, but the sheer amount of environmental destruction is enough to put off any traveler with a conscience.

For now, I wouldn’t recommend anyone to visit Halong Bay, at least until the bay is cleaned up and the situation controlled with new safety measures. –Nellie Huang of Wild Junket

MAYA BAY, KOH PHI PHI (Thailand)

If you love to travel, you’ve most likely seen The Beach , the 2000 movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio. Millions of people saw it, and it seems like most of them ended up traveling to Maya Bay Beach on Koh Phi Phi, where most of the film was shot.

Sadly, the place is a paradise no more, thanks to seemingly endless hordes of tourists. If you visit during the middle of the day, you’ll mostly see it packed with long-tail boats and people. Many are rowdy and obnoxiously drunk, leaving a trail of litter in their wake. The only way to see the real beauty of Maya Bay is to find a boat that will bring you there early in the morning, or around sunset.

The bay is located on Koh Phi Phi Leh. You can’t stay there overnight, but you can stay on the nearby (and bigger) island of Koh Phi Phi Don. Another option is taking a Maya Bay Sleep Aboard tour, where you sleep on the boat near this spot and get to spend almost a full day here. –Sonal & Sandro of Drifter Planet

PERHENTIAN ISLANDS (Malaysia)

When we got to Malaysia, my partner Karen couldn’t wait to show me the Perhentian Islands. Having been there previously on a diving trip, she raved about these tropical paradise islands, with their white sand beaches and crystal clear waters.

Unfortunately, what we found once we arrived was more like Paradise Lost. Every day we would notice these weird brown patches floating in the ocean. To this day I’m scared to think what they were. All I know is that everyone avoided them.

What was once an occasional speedboat taxi had now turned into a sea full of them. To make matters worse, they were driven by teens racing each other, making what should have been a leisurely swim into a worrisome nightmare. One day we even had a helicopter land right on the beach, unannounced!

The Perhentian Islands are becoming a victim of their own success. Instead of trying to keep the natural balance of things , there seems to be more and more tourism-related development going on. Unfortunately, if this keeps going, the pristine beauty of these islands will be lost forever. It’s in everyone’s interest to help preserve the Perhentians before it’s too late. –Paul Farrugia of Globalhelpswap

TOURISM IN AUSTRALIA

ULURU (Australia)

Australia’s most iconic natural attraction, Uluru (or Ayers Rock) is a symbol of the Outback that attracts more than 300,000 visitors every year.Believed to be millions of years old, this beautiful red rock juts imposingly out of the sand in the middle of the Australian desert.

Looming large at 1,142 feet, Uluru is considered a sacred site by the Indigenous Anangu people, the traditional owners of the land, and holds UNSECO World Heritage status for its ancient rock paintings. But mass tourism has caused numerous issues, provoking long-standing debates over whether or not tourists should be allowed to climb it.

Much of the controversy centers around respecting the Aboriginal community’s repeated requests that visitors not climb their sacred site. Tourists have been defecating, urinating, leaving trash, and vandalizing the rock face at the top of Uluru for years. Visitors have also been chipping off stones and defacing culturally significant engravings with name carvings of their own. As a result, a recent decision by local authorities will make Uluru off limits to climbers starting in October 2019.

To avoid the problems associated with overtourism, consider visiting during the wet season (January-March). The days are much hotter, but you’ll find very few tourists in the National Park. Early birds can head out for the base walk (6.5 miles, which takes around 3 hours) while everyone else is sleeping, getting close to the rock in complete silence. -Megan Jerrard of Mapping Megan

READ MORE: 10 Australian National Parks for your World Bucket List

TOURISM IN CENTRAL/SOUTH AMERICA

CARTAGENA (Colombia)

Colombia is a country whose reputation has been unfairly plagued by its past. In recent years, as the political and criminal situation calmed down considerably, new airline routes have opened up. As a result, Colombia is now bringing in quite a bit of tourism, attracting over 2.5 million visitors in 2016.

Cartagena, Colombia’s Caribbean tourism capital, attracts around 14% of those travelers. And while the city doesn’t seem overrun by visitors, the desire to cater to them has led to the gentrification of Getsemaní. Development of this ultra-hip neighborhood is largely being funded by international companies, who seem hell-bent on tourism profits regardless of the impact on the locals who live there.

Some of the more popular local beaches are so swamped with tourists, they’re too expensive for locals to get out to them. The tourism boom in Cartagena has also led to a staggering problem wherein young local girls are forced into prostitution to cater to foreigners.

If you’re visiting Cartagena, I recommend talking to the friendly locals. Ask them about their favorite places to go and things to do in the area. Support local businesses, and do your best to put money into the local economy rather than spending it to support international corporate interests. – Megan Starr

READ MORE: Best Attractions in Cartagena, Columbia

EASTER ISLAND (Chile)

Easter Island is best known for the mysterious Moai, gigantic stone statues created by the ancient Rapa Nui civilization. The Rapa Nui people carved the statues (some nearly 30 feet tall and weighing 80 tons), transported them to different sites, and erected them on ceremonial platforms. No one knows their purpose, but the 887 Moai are the tiny island’s main attraction.

Unfortunately, the sheer number of tourists (around 100,000 annually) are changing the nature of tourism on Easter Island. The Moai are very fragile, and tourists who touch the statues cause irreversible damage. Two important archaeological sites were closed to tourists in recent years due to deterioration.

Easter Island once collapsed under a population of 10,000. Now the island’s infrastructure and resources are being stressed by the growing surge of visitors. Available landfill area for non-recyclable waste is extremely limited.

Being a responsible tourist on Easter Island is easy. Just don’t touch the Moai, stick to marked trails, watch where you walk (archaeological sites are everywhere), respect local culture, and leave no waste. To avoid the crowds, travel off-season in winter (June to September) and skip the Tapati Festival in January. – Ketki Sharangpani of Dotted Globe

MACHU PICCHU/INCA TRAIL (Peru)

One special destination that’s sadly suffering from overtourism is Machu Picchu, and the increasingly popular Inca Trail that leads to it. Strict caps on visitors were put in place by the Peruvian government a few years back– 500 permits per day for the Inca Trail and 2500 per day for Machu Picchu. Yet still the famed site often sees double that number of visitors.

This is obvious in terms of countless irresponsible travelers ruining the natural beauty and mystical appeal with their ubiquitous selfie sticks. But what’s even worse is the area’s sanitation issues.

There’s toilet paper lining the hiking trails, squat toilets overflowing, and now the preservation of this precious site seems to be in danger.

There is good news: In the summer of 2017, the Peruvian government passed a new restriction for Machu Picchu visitors, requiring they enter with an official tour guide in groups of 16 or less.

Additionally, entry grants only a morning visit or an afternoon visit. So if if you want to spend the entire day, you’ll need to pay twice. While inside, visitors will need to stay on marked paths.

Hopefully new laws like these will help to ease the strain on this important UNESCO World Heritage site . –Jessie Festa of Jessie on a Journey

SALAR DE UYUNI (Bolivia)

It’s difficult to imagine how an area sprawling 4,085 square miles could ever feel crowded. But that’s just what’s happening at Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia’s famous salt pan.

Tourism has been a major contributor to the local economy, and even protected the Bolivia against Lithium mining. But the impacts haven’t been all good.

The number of visitors from the Uyuni departure point have far surpassed local infrastructure in recent years, and the city suffers from unmanaged waste.

While few studies have been conducted on the environe impacts of mass tourism, it’s impossible to imagine that hundreds of 4x4s have no impact on the ecosystem.

With more tourists feeding wildlife and treading on the plants and soil surrounding popular attractions, a change is inevitable.

From a human standpoint, increased competition has invited in big name travel companies. The prices of tours are WAY down, and margins for local operators have fallen with it.

The experience can still be incredible if you’re mindful about how you visit. Consider departing from Tupiza rather than Uyuni to support a different community.

Support the local businesses, tip your guides well, tread lightly, and leave the place like you found it so that it can be enjoyed by generations to come. – Taylor of Travel Outlandish

TOURISM IN EUROPE

AMSTERDAM (Netherlands)

Amsterdam is known all around the world as one of Europe’s most lovely cities. However in recent years the combination of drug-focused tourism and cheap budget flights have turned the city’s Centre district into a crowded mass tourism playground.

It finally reached a point in 2017 where overtourism was so bad, the government banned new tourist-oriented shops from opening in the Centre. They also started regulating Airbnb much more strictly, as the housing crisis in Amsterdam reached full bloom.

The rise in tourism has also made it very difficult for local residents in the Centre to find shops to do their errands in.

If you’re looking to contribute to a more sustainable future for Amsterdam, please consider staying outside of the Centre and NOT using an Airbnb.

Similarly, be sure to visit some of the residential neighborhoods, such as De Pijp, which are full of cute independent shops run by young Dutch entrepreneurs who are committed to making Amsterdam the best city in the Netherlands. –Karen Turner of Wanderlustingk

BARCELONA (Spain)

Barcelona has a lot to offer, including stunning Gaudi architecture, a rich tapas and wine culture, and (thanks to the 1992 Olympics) a two-mile stretch of beautiful beach.

The same Olympics that improved local quality of life by installing a municipal sailing center and public housing also put Barcelona on the map for international tourism, which grew to an unsustainable 32 million visitors in 2016.

A large number of these visitors are day-trippers, coming into the city on cruise ships carrying up to 5,000 passengers, all of whom descend on the nearby old town en masse. Barceloneta, once a quaint fisherman’s quarter, has become overcrowded.

AirBnB is forcing out locals, as renting out apartments to tourists is much more lucrative for owners than having long-term tenants. According to real estate portal Idealista, renewal contracts on apartments in 2016 saw an average price hike of over 20%.

Local shops around the Ramblas– some of them over 100 years old– are similarly being replaced by souvenir shops that can afford the rising rental prices for businesses. This gentrification is killing the area’s authenticity.

To avoid these tourism issues, seek out licensed hotels or apartments outside the most crowded areas of Barcelona. You can also visit popular tourist sites during the week, when the visitor numbers tend to be lower. – Edwina Dandler of Traveling German

CINQUE TERRE (Italy)

Up until I was 16 years old, I spent my summer holidays in a small seaside village in Liguria. Some of my grandma’s relatives lived near Cinque Terre, and we visited the area several times.

The five candy-colored villages were a popular day-trip destination, even in the 1980s. It was always hard to park, and the small beaches were packed, but no more so than elsewhere in the region.

In 2014 I returned to Cinque Terre after 15 years away, and I was shocked by what I saw. The quaint villages of my childhood were literally overrun with tourists.

The narrow, historic centre streets were a shuffling mass of bodies, litter was everywhere, and people treated local homes as if they were museums, walking in and posing for pictures.

A friend of mine from Vernazza (one of the five villages) told me that all these tourists are putting a terrible strain on the area.

First of all, these “bucket list” tourists spend little or no money– maybe a couple of euros for water and a focaccia. Tons of rubbish need to be removed daily, and locals are unable to enjoy their villages due to the multitudes of rude, rowdy people crowding them all summer.

My tip? Pretty much every town in Liguria has the same candy-colored houses that make Cinque Terre famous. I always recommend Levanto, a place with amazing nature and outdoor adventure! –Margherita Ragg of The Crowded Planet

DUBROVNIK (Croatia)

The Pearl of the Adriatic has been a popular tourist destination since the days when it was part of Yugoslavia. As if the appeal of the citrus-colored Old Town nestled atop the turquoise sea wasn’t enough, Dubrovnik also has a fascinating, tumultuous history that is very much still rooted in its local culture.

I’ve been lucky to call Dubrovnik home over the past three years. During this time, I’ve watched Game of Thrones and the cruise ship industry turn this small town into one of the trendiest destinations in Europe.

There’s no doubt this tourism boom has significantly boosted the local economy. But unfortunately the sea of mass tourism is pushing Dubrovnik far beyond its carrying capacity.

Just 40,000 people live in Dubrovnik, yet over 2 million people visit during the high season each summer. The Old Town is flooded with hot bodies and selfie sticks.

Cars honk at each other in bumper-to-bumper traffic. The buses are packed with tourists and a few locals (if they’re lucky enough to get on first).

Residents reclaim Dubrovnik in the winter months. The town celebrates local pride with holidays like St. Blaise Day and Badnjak, which are filled with dancing, eating, and singing traditional Croatian songs. This is when the city’s culture truly shines.

Efforts are currently underway to extend the tourist season beyond the summer and limit cruise ships. But living expenses are still increasing due to tourism, and many locals are struggling.

Many people, especially those from the Old Town, feel that Dubrovnik’s original spirit cannot be recovered. –Alexandra Schmidt of The Mindful Mermaid

When I spent time volunteering in the environmental field back in 2012, little did I know that one of the most striking destinations I had ever visited would soon become a victim of mass tourism.

Who knows if its popularity was caused by Game of Thrones , Star Wars , or the endless Instagram postings featuring Iceland ? Or maybe it’s because budget travel companies such as Wow Air sell low-cost flights from many European destinations.

Regardless, the harsh reality is that tourists arrive to find hotels and car rentals are expensive and in increasingly short supply during the high season (from June to August).

In June 2016, the situation was so chaotic that the government planned to restrict Airbnb rentals. Other measures to reduce the number of visitors are planned to be implemented soon.

So if you have Iceland on your bucket list, try to visit during the shoulder seasons (Spring or Fall) instead of Summer. Travelers and locals alike will benefit.

Most people believe everyone should be able to access the places we, as privileged people from first world countries, travel to regularly. But at what cost? Perhaps it’s time to rethink tourism as we know it, or else we’ll all have to live with the unfortunate consequences. -Inma Gregorio of A World To Travel

READ MORE: 10 Incredible Iceland Waterfalls

ISLE OF SKYE (Scotland)

The Isle of Skye in northwest Scotland boasts numerous natural landmarks. There’s the Old Man of Storr and the Quiraing range, the bizarre basalt formation Kilt Rock, Neist Point lighthouse, the Cuillin mountains, and of course the magical Fairy Pools.

Skye is Scotland’s largest island, and the only one that is accessible from the mainland via a bridge. And this is were the trouble starts…

The problem is that word on Skye’s stellar beauty has spread, making it one of Scotland’s most over-popular holiday destinations. While this brings invaluable income to local businesses, it’s proven problematic in terms of infrastructure and environmental impact.

Stories of cars spilling out of the limited parking lots onto the road and blocking locals’ daily commutes are overshadowed by even worse stories about inappropriate behavior by some tourists due to a lack of public toilet facilities.

Accommodations are seriously limited, which has caused the police to limit island visits to those with reservations only.

Responsible tourism to Skye is still possible. Allow yourself to go off the beaten path and support local businesses who give back to the community and act for the environment. Treat the island as if it was your home.

And finally, take a look around: Scotland’s Inner Hebrides offer many incredible islands that are waiting for you to discover them! –Kathi Kamleitner from Watch Me See

READ MORE: Top 10 Things To Do On The Isle of Skye

LISBON (Portugal)

If we compare Lisbon to other European cities, I believe there’s still a chance to save the Portuguese capital from overtourism.

Tourism in Lisbon is a great product: We have great weather and food, killer sunsets, a diverse culture and heritage, and a young population who speaks at least one foreign language fluently.

Tourism was the only industry bringing in a decent income when everything else seemed to be crashing under the economic recession. In fact, we now have tourists visiting all year round– there’s hardly a low season or shoulder season.

The housing crisis has been the biggest issue facing Lisbon. Locals can’t find affordable houses in the center of the city because landlords can make more money by listing their apartments on short-term rental websites (and paying less taxes). Not to mention the historic buildings being refurbished by foreign investment companies into luxury condos and more short-term rental units.

It’s a vicious cycle: Old-age tenants die or get evicted, the owner sells to the highest bidder, and the house becomes a short-term rental. There’s little that’s typical about Alfama or Mouraria these days. The old quarters are being stripped of their cultural identity.

The best way a traveler can stop this is by booking a hotel instead of a short-term rental. – Sandra Henriques Gajjar of Tripper

READ MORE: Things To Do In Portugal For Nature Lovers

PRAGUE (Czech Republic)

Travel is a good thing, for the most part. Most destinations rely on the economic gains from this $7 trillion a year industry, and there are countless benefits to travelers themselves. But when tourism grows at an unsustainable, it can be damaging both to locals and their environment. Prague is a perfect example of mass tourism.

For me, Prague was once a fairytale bucket list destination. But now that over tourism has clouded the experience, it no longer seems like such a magical place.

The city is crowded no matter what time year you visit, with people and vendors elbow to elbow on the Charles Bridge. New developments are often under construction, which detracts from the city’s beauty. Prague has also become more expensive, both for tourists and locals alike.

To avoid huge crowds, become a morning person to beat the crowds. Connect with locals via Facebook groups or Couchsurfing, and explore with expats or locals who know the best places to visit.

Prague is still a stunning city, but for now I avoid it and explore less touristy places instead. –Olga Maria of DreamsInHeels

SANTORINI (Greece)

Not all that long ago, Santorini was a small, rocky, relatively unknown Greek Island. But it has risen in recent years to become one of the most iconic places to visit in Greece due largely to its whitewashed villages, blue-domed churches, and incredible sunsets.

But many of the locals who once lived in this Mediterranean paradise have been driven out due to rising property costs. The price for Greeks to ferry to work from neighboring islands is prohibitively high.

The locals who are left are invaded by disrespectful visitors who often destroy their property while trying to get the perfect selfie. And when it comes to the environment, the island’s main roads are littered with trash left by indifferent tourists.

Avoiding the Santorini crowds completely is almost impossible, especially if you hope to view the sunset in iconic spots like Oia. However, the island’s east-facing side affords equally beautiful views, and the gorgeous resorts there are more affordable and just as luxurious.

Take some time on the south side of the island for wine tasting and wandering through villages. Also consider going to Santorini in the off-season, when it’s cheaper and less crowded.

Three times as many hotels will be staying open throughout the winter in order to help encourage better distribution of the influx of tourists. – Eileen Cotter Wright of Pure Wander

READ MORE: The Best Places To Visit in Greece in 40 Fantastic Photos

SVANETI (Georgia)

Situated on the southern slopes of the Greater Caucasus mountains and surrounded by 16,000-foot peaks, stunning Svaneti is one of the fastest growing tourism destinations in Georgia.

The mountains, remoteness, and unique indigenous traditions make it an ideal destination for hiking, trekking, wildlife, and cultural tourism. However, negative impacts of tourism can already be seen.

When I first visited Svaneti in 2001, I didn’t see any other tourists for a week. In 2014 there were 14,160 visitors, and by 2016 there were 18,347. Because most tourists go to Mestia (2,700 inhabitants) and hike/drive east towards Ushguli (200 inhabitants) between June-September, it’s getting harder to accommodate them.

New concrete guesthouses are being built randomly, without any permission. But they’re incompatible with the local cultural and architectural heritage and ultimately spoil the picturesque landscape.

Farmland has been reduced to build new accommodations and ski facilities, causing problems with local food supplies. There’s a growing issue with solid waste disposal in villages and along the hiking trails. And the famous Svan hospitality is vanishing: Getting invited to dine with the local family is now very rare.

Svaneti is at risk of losing its traditional Georgian charm. To avoid the crowds , head west of Mestia, where tourism has hardly been developed at all. – Marta Mills of One Planet Blog

VENICE (Italy)

There is a certain aura of magic and mystery about Venice. For decades, visitors have been unable to resist the allure of the city’s romantic canals, singing gondoliers, picturesque bridges and grand architecture. The “City of Bridges” tops the ‘must visit cities in Europe’ lists year after year but for how much longer?

Aside from its risk of sinking and its threat from flooding, Venice is a city under populated and over-crowded.

Mass tourism attributed to the mega-cruise ships is causing irreversible damage not only to the fragile lagoon ecosystem but the city itself. A city that only in-habits under 55,000 residents yet welcomes over 30 million visitors a year.

Venice and its Lagoon have long been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. But due to mass-tourism, not only does it risk losing its status, it faces entering the “Endangered” list, a list normally reserved for ruins and sites damaged by war.

Vandalism, crime, destruction of some historical sites and tourist stupidity has already caused tension between residents and visitors.

To add to its woes, cruise ship visitors lack of overnight stays means city tax (that benefits the city) is not being paid, local businesses in the same “tourist” areas are strained and local necessity shops have been closed to only be replaced with souvenir stalls, further pushing locals out of their own city.

Venice is a city that strongly relies on tourism, and while many believe the ban of large ships to Venice would solve the problem, there is so much more that needs to be done to ensure this charming city continues to thrive, and be preserved for generations to come.

To avoid Venice overtourism, visit out-side of the peak seasons (so October-December & February – April) and ensure you’re a responsible tourist! –Samantha & Leonardo of The Wandering Wanderlusters

READ MORE: Le Marche, Italy: A Local’s 7 Favorite Places To Visit

TOURISM IN NORTH AMERICA

DENALI NATIONAL PARK, ALASKA (USA)

Most people wouldn’t think of mass tourism when considering Alaska, the wildest state in the USA . But having been there before the Alaska Highway was paved all the way through in 1992, I can see a major difference.

Before the opening of the highway, Alaska was a great adventure . You were lucky if you could get through the state without getting stuck in the mud somewhere. Now you can just cruise through, perhaps seeing the odd construction site along the way where last winter’s potholes are being repaired.

Denali National Park has been especially impacted by tourism development. Before 1992 there were only a few lodges and cabins along the Nenana River, and a campground with very basic facilities. Today you’ll find luxury resorts, a Good Sam Park, and a boardwalk mall with fast food and ice cream joints.

You have to wait in a line of jostling tourists to enter the park on one of the park’s buses. Photo stops along the park road are precisely timed, and the feeling of being out in the wilderness is lost in the process.

My tip? Skip the bus tours entirely and go wilderness hiking in Denali to experience the park’s true, wild nature. – Monika Fuchs of Travel World Online

READ MORE: Denali National Park: Exploring America’s Last Great Frontier

BANFF, ALBERTA (Canada)

I grew up in a small town near Banff, one of the most frequently visited destinations in Canada. Located in the Canadian Rockies, it’s home to several of Canada’s most famous ski resorts.

Tourism there created a unique set of social problems caused primarily by the fact that, as a town located inside a National Park, Banff had strict boundaries. Therefore it wasn’t able to expand beyond the 4.9 square kilometers allotted to it.

The extreme popularity of the destination and the limits on expansion means that the town’s limited real estate is extremely expensive and almost entirely devoted to high-end tourism.

Nearly everyone who lived there worked in the service industry (as I did). So they couldn’t afford the few apartments available, and were forced to live in small, dingy dormitories provided by their employers. Seasonal hiring/firing made for high turnover, which created a transient community locals were reticent to embrace.

The result was a very strange society of short-term locals and a nearly ubiquitous binge-drinking party culture. Think of a college town where all the students have enough money to get drunk every night and can leave any time they want.

Banff is by no means a terrible town. But overtourism has turned it from a quaint skiing community into a churn-and-burn business more focused on pleasing tourists than providing an affordable quality of life for locals. –Matt Gibson of Xpat Matt

MANHATTAN, NEW YORK CITY (USA)

Manhattan is the most-visited part of NYC, the USA ’s top port of entry, top generator of tourism revenue, and top big-city destination. Tens of millions of people visit every year – a fact that’s regularly emphasized by marketing org NYC & Company.

But how many millions are too many, even in a megacity? Parts of Manhattan have hit their carrying capacity– the point beyond which bigger tourism numbers just aren’t better.

As a native New Yorker, I studiously avoid places like Times Square and Rockefeller Center during heavy travel periods. They’re not pleasant to visit for anyone, whether tourists or locals.

But Manhattan’s problems run deeper. There are vital questions about the degree to which the money tourists spend in Manhattan adds to the local economy.

The gross value may tell one tale, but when factoring the economic impact of tourism, the economic leakage (money benefiting businesses based elsewhere), the hard and soft costs of managing tourism, and the relatively shallow spread of benefits, the economic yield might not make as much economic sense.

Fortunately, NYC is considering alternative tourism strategies. The new “True York City” campaign encourages visitors to explore and engage more deeply with the area.

Perhaps it’s the start of real thinking about the quality of the NYC tourism experience, rather than the quantity. –Ethan Gelber of The Travel Word

MAUI, HAWAII (USA)

Maui has topped “ Best Island in the World ” ratings for years. It’s no surprise, considering its perfect weather, perfect beaches, and perfectly picturesque views. But all this perfection comes at a cost, which is the degradation of my once-perfect vacation destination .

At just 727 square miles, Maui is a small island, yet it sees around 3 million tourists each year. Those visitors drive up local prices, crowd the more popular areas, and make it harder and harder to relax in the land of aloha.

There is also the negative environmental impact of tourism, with several endemic species needing additional protection.

One especially egregious example of the effects of tourism on Maui is Molokini. This tiny, fingernail-shaped atoll just off the coast of Maui is a popular spot for snorkeling. When I first booked a half-day snorkel trip in the early 2000s, it was fantastic.

But when I returned in 2010, there were so many packed catamarans that the snorkeling area was full of swimmers. It’s not much fun to be constantly on the lookout to avoid getting kicked in the face, and it’s likely even less fun for the fish that live there. Or did.

Maui depends on tourism for its economic health, so it’s hard to hate on the island for being so popular. But I’d love it if there was a better balance between the needs of the island’s coffers and the health of its flora and fauna. –Jen Miner of The Vacation Gals

READ MORE: Maui, Hula & Hawaiian Culture

YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK (USA)

Located in the northwestern corner of Wyoming, Yellowstone National Park is the gem that started the United States’ National Park system . In the last 10 years, tourism has increased by 40%, with over 4.2 million visiting the park in 2016.

This dramatic increase has caused numerous tourism problems. The first is visitors walking off marked trails, causing environmental damage by killing the vegetation (which leads to erosion issues).

The second problem is with visitors who throw items such as coins and food into the geothermal features, which harm the geothermal algae. Some visitors even walk in the geothermal features, which can lead to death.

Another big issue is human/wildlife encounters. Yellowstone’s animals are learning bad habits that make them think people are food sources. Bears can become aggressive and dangerous when fed.

Poorly informed visitors will involve themselves in an “animal rescue” rather than letting nature take its course (see: the couple who put a baby Bison in the back of their car ).

The best way to avoid the masses is to avoid visiting Yellowstone during the summer. May and October are a great time to take advantage of warmer weather without dealing with major crowds. –Jennifer Melroy of Made all the Difference

YUCATAN PENINSULA (Mexico)

From Playa del Carmen to Cancun, the uncontrolled surge of tourism to the Yucatan Peninsula has turned much of the region into one massive all-inclusive resort. What once was a series of pristine jungle and marine ecosystems is gradually being destroyed by chaotic urbanization.

Nearly 10 million visitors a year descend upon Quintana Roo (the Mexican state which includes the Yucatan coast), and their piña coladas and suntan lotion are suffocating the ecosystems with plastic bottles and organic waste.

Most locals don’t profit from this rapid rise of tourism revenue: All-inclusive resorts rarely hire indigenous natives, and these resorts rarely give back to the community.

Once a quiet fishing village, Playa Del Carmen has lost all local appeal. It’s become a throbbing beach town dominated by a tourist strip filled with splashy resorts, booming nightclubs, and drugs. Violence and theft has surged in the surrounding communities while police are occupied with patrolling the tourist areas.

If you do head to Playa del Carmen or Cancun, don’t stay at an all-inclusive. Understand that unchecked tourism has had a negative impact, and let that guide your spending. Dine at local restaurants. Shop at locally-owned businesses. Chat to local people.

It’s really the only way to ensure your visit to this mass tourism hotspot has positive benefits. –Mike Jerrard of Waking Up Wild

READ MORE : Riviera Maya: Tulum, Coba Mayan Ruins, Monkeys & More!

About the Author

Green Global Travel is the world's #1 independently owned ecotourism website encouraging others to embrace sustainable travel, wildlife conservation, cultural preservation, and going green tips for more sustainable living.

We've been spotlighted in major media outlets such as the BBC, Chicago Tribune, Forbes, The Guardian, Lonely Planet, National Geographic, Travel Channel, Washington Post and others.

Owned by Bret Love (a veteran journalist/photographer) and Mary Gabbett (business manager/videographer), USA Today named us one of the world's Top 5 Travel Blogging Couples. We were also featured in the 2017 National Geographic book, Ultimate Journeys for Two, for which we contributed a chapter on our adventures in Rwanda. Other awards we've won include Best Feature from both the Caribbean Tourism Organization and the Magazine Association of the Southeast.

As Seen On…

Join the 300,000+ people who follow Green Global Travel’s Blog and Social Media

What is overtourism and how can we overcome it?

The issue of overtourism has become a major concern due to the surge in travel following the pandemic. Image: Reuters/Manuel Silvestri (ITALY - Tags: ENTERTAINMENT)

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Joseph Martin Cheer

Marina novelli.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Travel and Tourism is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, travel and tourism.

Listen to the article

- Overtourism has once again become a concern, particularly after the rebound of international travel post-pandemic.

- Communities in popular destinations worldwide have expressed concerns over excess tourism on their doorstep.

- Here we outline the complexities of overtourism and the possible measures that can be taken to address the problem.

The term ‘overtourism’ has re-emerged as tourism recovery has surged around the globe. But already in 2019, angst over excessive tourism growth was so high that the UN World Tourism Organization called for “such growth to be managed responsibly so as to best seize the opportunities tourism can generate for communities around the world”.

This was especially evident in cities like Barcelona, where anti-tourism sentiment built up in response to pent-up frustration about rapid and unyielding tourism growth. Similar local frustration emerged in other famous cities, including Amsterdam , Venice , London , Kyoto and Dubrovnik .

While the pandemic was expected to usher in a new normal where responsible and sustainable travel would emerge, this shift was evidently short-lived, as demand surged in 2022 and 2023 after travel restrictions eased.

Have you read?

Ten principles for sustainable destinations: charting a new path forward for travel and tourism.

This has been witnessed over the recent Northern Hemisphere summer season, during which popular destinations heaved under the pressure of pent-up post-pandemic demand , with grassroots communities articulating over-tourism concerns.

Concerns over excess tourism have not only been seen in popular cities but also on the islands of Hawaii and Greece , beaches in Spain , national parks in the United States and Africa , and places off the beaten track like Japan ’s less explored regions.

What is overtourism?

The term overtourism was employed by Freya Petersen in 2001, who lamented the excesses of tourism development and governance deficits in the city of Pompei. Her sentiments are increasingly familiar among tourists in other top tourism destinations more than 20 years later.

Overtourism is more than a journalistic device to arouse host community anxiety or demonize tourists through anti-tourism activism. It is also more than simply being a question of management – although poor or lax governance most definitely accentuates the problem.

Governments at all levels must be decisive and firm about policy responses that control the nature of tourist demand and not merely give in to profits that flow from tourist expenditure and investment.

Overtourism is often oversimplified as being a problem of too many tourists. While that may well be an underlying symptom of excess, it fails to acknowledge the myriad factors at play.

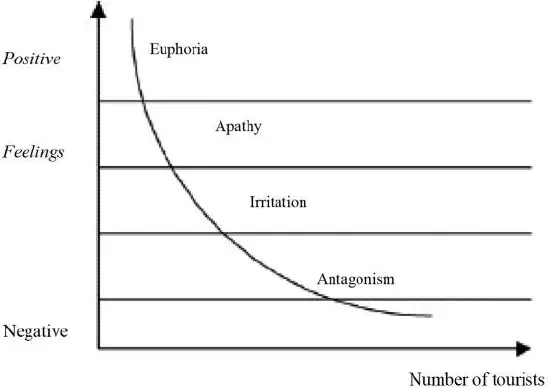

In its simplest iteration, overtourism results from tourist demand exceeding the carrying capacity of host communities in a destination. Too often, the tourism supply chain stimulates demand, giving little thought to the capacity of destinations and the ripple effects on the well-being of local communities.

Overtourism is arguably a social phenomenon too. In China and India, two of the most populated countries where space is a premium, crowded places are socially accepted and overtourism concerns are rarely articulated, if at all. This suggests that cultural expectations of personal space and expectations of exclusivity differ.

We also tend not to associate ‘overtourism’ with Africa . But uncontrolled growth in tourist numbers is unsustainable anywhere, whether in an ancient European city or the savannah of a sub-Saharan context.

Overtourism must also have cultural drivers that are intensified when tourists' culture is at odds with that of host communities – this might manifest as breaching of public norms, irritating habits, unacceptable behaviours , place-based displacement and inconsiderate occupation of space.

The issue also comes about when the economic drivers of tourism mean that those who stand to benefit from growth are instead those who pay the price of it, particularly where gentrification and capital accumulation driven from outside results in local resident displacement and marginalization.

Overcoming overtourism excesses

Radical policy measures that break the overtourism cycle are becoming more common. For example, Amsterdam has moved to ban cruise ships by closing the city’s cruise terminal.

Tourism degrowth has long been posited as a remedy to overtourism. While simply cutting back on tourist numbers seems like a logical response, whether the economic trade-offs of fewer tourists will be tolerated is another thing altogether.

The Spanish island of Lanzarote moved to desaturate the island by calling the industry to focus on quality tourism rather than quantity. This shift to quality, or higher yielding, tourists has been mirrored in many other destinations, like Bali , for example.

Dispersing tourists outside hotspots is commonly seen as a means of dealing with too much tourism. However, whether sufficient interest to go off the beaten track can be stimulated might be an immoveable constraint, or simply result in problem shifting .

Demarketing destinations has been applied with varying degrees of success. However, whether it can address the underlying factors in the long run is questioned, particularly as social media influencers and travel writers continue to give attention to touristic hotspots. In France, asking visitors to avoid Mont Saint-Michelle and instead recommending they go elsewhere is evidence of this.

Introducing entry fees and gates to over-tourist places like Venice is another deterrent. This assumes visitors won’t object to paying and that revenues generated are spent on finding solutions rather than getting lost in authorities’ consolidated revenue.

Advocacy and awareness campaigns against overtourism have also been prominent, but whether appeals to tourists asking them to curb irresponsible behaviours have had any impact remains questionable as incidents continue —for example, the Palau Pledge and New Zealand’s Tiaki Promise appeal for more responsible behaviours.

Curtailing the use of the word overtourism is also posited – in the interest of avoiding the rise of moral panics and the swell of anti-tourism social movements, but pretending the phenomenon does not exist, or dwelling on semantics won’t solve the problem .

Solutions to address overtourism

The solutions to dealing adequately with the effects of overtourism are likely to be many and varied and must be tailored to the unique, relevant destination .

The tourism supply chain must also bear its fair share of responsibility. While popular destinations are understandably an easier sell, redirecting tourism beyond popular honeypots like urban heritage sites or overcrowded beaches needs greater impetus to avoid shifting the problem elsewhere.

Local authorities must exercise policy measures that establish capacity limits, then ensure they are upheld, and if not, be held responsible for their inaction .

Meanwhile, tourists themselves should take responsibility for their behaviour and decisions while travelling, as this can make a big difference to the impact on local residents .

Those investing in tourism should support initiatives that elevate local priorities and needs, and not simply exercise a model of maximum extraction for shareholders in the supply chain.

How is the World Economic Forum supporting the development of cities and communities globally?

The Data for the City of Tomorrow report highlighted that in 2023, around 56% of the world is urbanized. Almost 65% of people use the internet. Soon, 75% of the world’s jobs will require digital skills.

The World Economic Forum’s Centre for Urban Transformation is at the forefront of advancing public-private collaboration in cities. It enables more resilient and future-ready communities and local economies through green initiatives and the ethical use of data.

Learn more about our impact:

- Net Zero Carbon Cities: Through this initiative, we are sharing more than 200 leading practices to promote sustainability and reducing emissions in urban settings and empower cities to take bold action towards achieving carbon neutrality .

- G20 Global Smart Cities Alliance: We are dedicated to establishing norms and policy standards for the safe and ethical use of data in smart cities , leading smart city governance initiatives in more than 36 cities around the world.

- Empowering Brazilian SMEs with IoT adoption : We are removing barriers to IoT adoption for small and medium-sized enterprises in Brazil – with participating companies seeing a 192% return on investment.

- IoT security: Our Council on the Connected World established IoT security requirements for consumer-facing devices . It engages over 100 organizations to safeguard consumers against cyber threats.

- Healthy Cities and Communities: Through partnerships in Jersey City and Austin, USA, as well as Mumbai, India, this initiative focuses on enhancing citizens' lives by promoting better nutritional choices, physical activity, and sanitation practices.

Want to know more about our centre’s impact or get involved? Contact us .

National tourist offices and destination management organizations must support development that is nuanced and in tune with the local backdrop rather than simply mimicking mass-produced products and experiences.

The way tourist experiences are developed and shaped must be transformed to move away from outright consumerist fantasies to responsible consumption .

The overtourism problem will be solved through a clear-headed, collaborative and case-specific assessment of the many drivers in action. Finally, ignoring historical precedents that have led to the current predicament of overtourism and pinning this on oversimplified prescriptions abandons any chance of more sustainable and equitable tourism futures .

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Travel and Tourism .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How Japan is attracting digital nomads to shape local economies and innovation

Naoko Tochibayashi and Naoko Kutty

March 28, 2024

Turning tourism into development: Mitigating risks and leveraging heritage assets

Abeer Al Akel and Maimunah Mohd Sharif

February 15, 2024

Buses are key to fuelling Indian women's economic success. Here's why

Priya Singh

February 8, 2024

These are the world’s most powerful passports to have in 2024

Thea de Gallier

January 31, 2024

These are the world’s 9 most powerful passports in 2024

South Korea is launching a special visa for K-pop lovers

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

- CORONAVIRUS COVERAGE

Mass tourism has troubled Mallorca for decades. Can it change?

As the Spanish island begins to welcome travelers after pandemic lockdowns, some locals are looking for more sustainable paths.

Mallorca’s picturesque Ca los Camps beach lies near a forest sheltering Bronze Age megaliths called talaiots— and far from infamous megaresort areas such as Magaluf. With the current reduction in tourists, “the beauty of Mallorca is now in front of us,” says photographer Pep Bonet, who used infrared imagery to highlight the ethereal quality of the island in its present state.

The first days of June dawned in a Spain hushed by the coronavirus pandemic. By then, more than 27,000 Spaniards had died of COVID-19, and the country was midway through a 10-day mourning period honoring their lives. Flags flickered at half mast. Families, faces covered, grieved beside newly built tombs.

On Mallorca, the largest of Spain ’s Balearic Islands, whitewashed hotels stood empty in the spring sunshine. Since the middle of March, when the archipelago’s airports snapped shut, the nearby beaches had been devoid of tourists. The economic downturn has deepened the pandemic’s toll.

“We have about 200,000 jobs that depend on tourism,” says Rosana Morillo, the director general of tourism in the Balearic Islands. Roughly 25 percent of the islands’ economy comes directly from tourism, Morillo estimates; add the indirect impact, and the number is closer to 35 percent.

The pandemic has meant a devastating loss of income on the archipelago, and for some, ushering back visitors has been a top priority. But visitation cuts both ways in the Balearic Islands, where high-rise resorts cater to crowds looking for sun-splashed beaches and free-flowing drinks. To many locals, tourism is an economic boon that’s become a crushing burden.

Long before overtourism became a pressing concern from Barcelona to Venice , the Balearic Islands were a byword for a travel industry run amok. When tourism researchers refer to out-of-control development that values short-term profit over sustainability, they call it balearización.

Suddenly, amid the pandemic’s heartbreak and loss, islanders got an unexpected glimpse of a different life.

The cove of Sa Calobra is one of the few ways to access the sea from the Serra de Tramuntana, a mountain range designated a UNESCO World Heritage site under the Cultural Landscape category for its centuries-old terraced farming in steep terrain.

Located on the slopes of Puig Major and Morro de Cúber, the reservoir of Cúber—along with the Gorg Blau reservoir—supplies water to the city of Palma de Mallorca and the surrounding area.

An aerial view of Es Llombards, near Mallorca’s south coast, shows a quiet village in an area normally filled with tourists. The slowdown caused by the pandemic “will support a more sustainable island,” says photographer Pep Bonet.

A time of quiet

It was a few weeks after the tourists left Mallorca when Pere Tomas walked out on his apartment terrace and saw the massive dark wings of a cinereous vulture wheeling high above. Tomas, a local guide who leads nature tours , made a note of it. Locked down and out of work, he was tracking resurgent wildlife on an island hushed by the pandemic.

“We could see very rare species that before we had only seen very far in the countryside,” he says. “There was less disturbance everywhere.”

When strict lockdowns lifted in early June, islanders emerged from their homes to find a sun-washed coastline that—seemingly for the first time in memory—was empty of tourists in the high season.

With the drone of sightseeing boats silenced, fishermen reeled nets from gin-clear bays to the sound of wind and waves. On the island’s northern edge, photographer Pep Bonet hiked mountain pathways where, instead of German and English, he heard the shushed consonants of the archipelago’s own Mallorquín dialect.

“Walking the beaches was incredible,” recalls professor Julio Batle, who reveled in pristine sand free of the partying crowds that this Mediterranean island is known for. “Even when I was a kid, there were too many tourists, so it was a new situation,” says Batle, who studies sustainable tourism and economics at the Universitat de les Illes Balears . “It was strange, and beautiful.”

In recent years, cruise ships have swarmed the harbor at Palma de Mallorca, shown here in 1929.

Near Palma de Mallorca, El Arenal beach drew crowds of hard-partying holiday makers in August 2019. These booze-fueled trips are “almost a rite of passage for many Brits and Germans,” says photographer Pep Bonet.

( Discover the dazzling Spanish national park in Catalonia .)

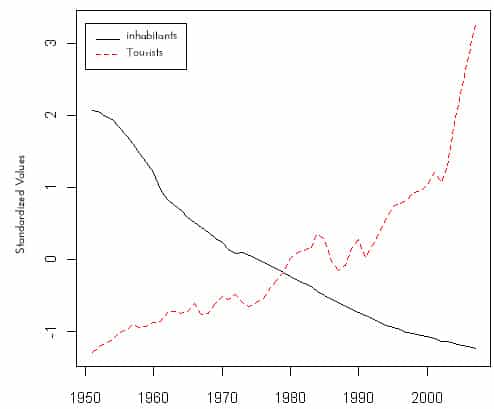

It’s also a stark contrast from the usual scene on Mallorca, where the sheer scale of pre-pandemic tourism was overwhelming. Some 11.8 million visitors flooded Mallorca in 2019, dwarfing the local population of under a million. The cost of living has skyrocketed, a trend aggravated by the conversion of family homes into vacation rentals .

Environmental impacts have been grave. Tourism pushed water usage to the brink. Developments chewed into fragile hillsides, and planes plus vast fleets of rental cars generated air pollution that left some locals in masks long before the pandemic began.

On a hot July day in 2017, planes passed through Mallorca’s Son Sant Joan airport at a record-breaking rate of one every 90 seconds. It’s no surprise the cinereous vultures stayed away.

How tourism devoured the island

An observer, taking in Mallorca’s ivory-colored beaches and turquoise coves, might easily see the island’s double-edged tourism industry as inevitable, the simple arithmetic of sun, sand, and sea. But the scale of tourism here isn’t haphazard: It’s the product of intentional development.

In the 1950s, Spain’s fascist regime saw tourism as a sorely needed source of revenue; the isolated government was hungry for foreign currency. Officials loosened the borders and encouraged beach development.

In Mallorca, hotels ballooned in size, eventually leaving Palma—the island’s capital—fenced in by high-rises built to attract budget travelers in the largest possible numbers. Cruise tourism has followed the same steep growth curve, with some 500 ships carrying 2 million passengers arriving in Palma each year.

But in recent years, many locals have pointed out that if mass tourism was a choice, it’s not too late to choose something else.

The local government seems to agree, expressing interest in a more sustainable model. In 2016, a tourist tax was introduced to raise funds for environmental restoration. Resort towns have cracked down on the tourist misbehavior that most wearies islanders, hoping to trade partiers for families interested in local culture.

Can the future be different?

For now, Mallorca has largely escaped the worst of the virus, with under 2,300 confirmed cases as of July 17. And despite the terrible toll of the pandemic on both lives and livelihoods globally, some residents are wondering if it might also present a chance to remake tourism on a smaller scale that favors meaningful encounters over the masses.

“I ask locals ‘how many of you have had the chance to spend quality time with tourists?’” explains Batle, the researcher. He says that few people he meets have had those authentic, one-on-one interactions. It’s a problem of scale, and one that Batle believes the pandemic could help upend. “The window is open for changes.”

Marine biologists and Cleanwave founder Philipp Baier have created a floating laboratory aboard a classic 1965 yacht, Falcao Uno. Along with citizen scientists, they investigate invasive species and microplastic pollution, a new way to engage Mallorca’s tourists in conservation of the Mediterranean Sea.

Jaume Catany is a farmer working at Circle Carbon Labs, a research and development facility that regenerates soil with waste from agriculture and sequesters carbon through a circular economy model.

A fisherman since the age of 13, Gori Maiol now captains a llaüt (traditional Mallorcan boat) and works with Vincent Colom. They use sustainable fishing practices like casting nets with bigger holes so small fish can escape and tossing small lobsters back into the sea.

“I think the pandemic is going to change all of our lives,” agrees Morillo, the director general of tourism. Nightclubs and boozy beach parties already seem like relics in a world grappling with infection. And it’s clear that the scale of tourism will be sharply reduced for the foreseeable future. Even the most optimistic observers think that just 50 percent of Palma hotels will open by the end of July.

( Related: In Florence, a centuries-old tradition fights for survival .)

As travelers start returning to the islands, Morillo hopes they’ll seek out natural landscapes and local culture, swapping coastal megaresorts for cycling through the mountains, stargazing, and sampling the gastronomy scene.

Or birdwatching. After months of lockdown, naturalist Pere Tomas finally left his apartment to lead a birdwatching tour in early June, guiding a British couple deep into the Albufera wetlands, where they saw endangered red-knobbed coots and a rare squacco heron.

Pandemic or not, thousands of migratory birds will return to these wetlands in the fall. Tourists have come back even sooner; the first planeloads of German vacationers touched down in mid-June. To try to avoid any virus outbreaks, the Balearics made masks mandatory in public places (but not the beach), as of July 13. And after a few recent incidents with drunken tourists, authorities shut down Palma’s main party strip . With clubs and discos closed, there’s an opening to discover a different side of island life.

Even after decades of intense tourism, many locals agree that it is Mallorca’s wildness that retains the power to astonish visitors—at least those willing to go beyond the most densely developed parts of the coast. “They get here and they see that actually there are big open spaces,” says longtime resident Timothy Pennell.

He runs La Serranía retreat in the UNESCO-listed Serra de Tramuntana mountains of northern Mallorca, a steep landscape shaped by thousands of years of small-scale farming. Stone-walled terraces cascade down hillsides knit together by olive groves and fruit orchards.

Speaking from his home in the middle of June, Pennell panned his camera phone across a landscape gone lush with spring. Heat hazed the view, and a mountain breeze stirred the leaves. Sheep grazed in the background.

“It’s quiet,” he said. Many here hope that a little of that quiet will remain.

Related Topics

- CORONAVIRUS

- CULTURAL TOURISM

- ADVENTURE TRAVEL

- OVERTOURISM

- SUSTAINABLE TOURISM

You May Also Like

One of Italy’s most visited places is an under-appreciated wine capital

How can tourists help Maui recover? Here’s what locals say.

Free bonus issue.

In this fragile landscape, Ladakh’s ecolodges help sustain a way of life

10 whimsical ways to experience Scotland

The essential guide to visiting Scotland

25 breathtaking places and experiences for 2023

They inspire us and teach us about the world: Meet our 2024 Travelers of the Year

- Perpetual Planet

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Photography

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Gory Details

- 2023 in Review

- Best of the World

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Linkedin Weekly Newsletters

- RT Notes from the Field

- Travel Tomorrow

- Responsible Tourism enters its 3rd Decade.

- Why Responsibility?

- Accountability and Transparency

- Origins of the Cape Town Declaration

- About Responsible Tourism Partnership

- Harold Goodwin

- Media Links

- Privacy Policy

- 2022 Responsible Tourism Charter

- What is Responsible Tourism?

- What does Responsible mean?

- Addressing OverTourism

- Responsible Tourism at WTM London 2023

- WTM London 2022

- WTM London 2021

- WTM London 2020

- WTM London 2019

- WTM London 2018

- WTM London 2017

- WTM London 2016

- WTM London 2014

- WTM London 2013

- WTM Africa 2024

- WTM Africa 2023

- WTM Africa 2022

- WTM Africa 2021

- WTM Africa 2020

- WTM Africa 2018

- WTM Africa 2017

- WTM Africa 2016

- WTM Africa 2015

- WTM Latin America 2023

- Latin America Responsible Tourism 2023

- WTM Latin America 2022

- WTM Latin America 2020

- WTM Latin America 2018

- WTM Latin America 2017

- WTM Latin America 2015

- Arabian Travel Market 2023

- Arabian Travel Market 2022

- Arabian Travel Market 2021

- Arabian Travel Market 2020

- Arabian Travel Market 2016

- 2023 RT Awards Cycle

- 2022 WTM RT Awards Cycle

- Global Awards 2021

- WTM, Global Responsible Tourism Awards 2021

- World Responsible Tourism Awards 2020

- World Responsible Tourism Awards 2019

- World Responsible Tourism Awards 2018

- World Responsible Tourism Awards 2017

- World Responsible Tourism Awards 2004 to 2016

- Africa Responsible Tourism Awards 2023

- Africa Responsible Tourism Awards 2022

- Africa Responsible Tourism Awards 2020

- Africa Responsible Tourism Awards 2019

- Africa Responsible Tourism Awards 2018

- Africa Responsible Tourism Awards 2017

- Africa Responsible Tourism Awards 2016

- Africa Responsible Tourism Awards 2015

- India Awards

- India ICRT Awards 2024

- India ICRT Awards 2023

- India ICRT Awards 2022

- ICRT India Responsible Tourism Awards 2021

- India Responsible Tourism Awards 2021

- India Responsible Tourism Awards 2020