Fifty years ago, on December 19, 1972, the Apollo 17 astronauts splashed down in the Pacific. They were the last humans to visit the Moon —and the last to be more than 400 miles from the Earth. Since that date, astronauts have only been in low Earth orbit. It is thus richly symbolic that NASA’s Artemis I mission had its own Pacific splashdown recently, during Apollo 17’s 50th-anniversary celebration. It was, of course, only an uncrewed test of the space agency’s new lunar craft. Humans will not fly around the Moon for two to three years. Why has it taken more than five decades to send humans back to the Moon?

It was certainly not Apollo 17 commander Eugene Cernan ’s expectation when he stepped off the lunar surface for the last time on December 14, 1972 . He was aware, as was everyone in the space agency, that lean times were ahead. Two years earlier, NASA had deleted Apollos 18 and 19 to save money and focus on the Space Shuttle. Congress and two presidential administrations had been cutting NASA’s budget since 1967 as the Vietnam War, poverty, urban problems, and environmental crises made the space program less and less popular. Once Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped on the surface in July 1969, many Americans wondered why we didn’t stop. We had beaten the Soviets and proved American technological superiority—the fundamental purpose of Project Apollo. Although the later landings yielded a huge scientific haul of samples and data, the public did not much care about lunar science’s value to understanding solar system history. It seemed like a waste of billions of dollars to voters preoccupied with other problems. Thus, Cernan knew it could be two decades before a new human lunar program would be feasible. But it was hard to believe that American astronauts wouldn’t make it back before the end of the century.

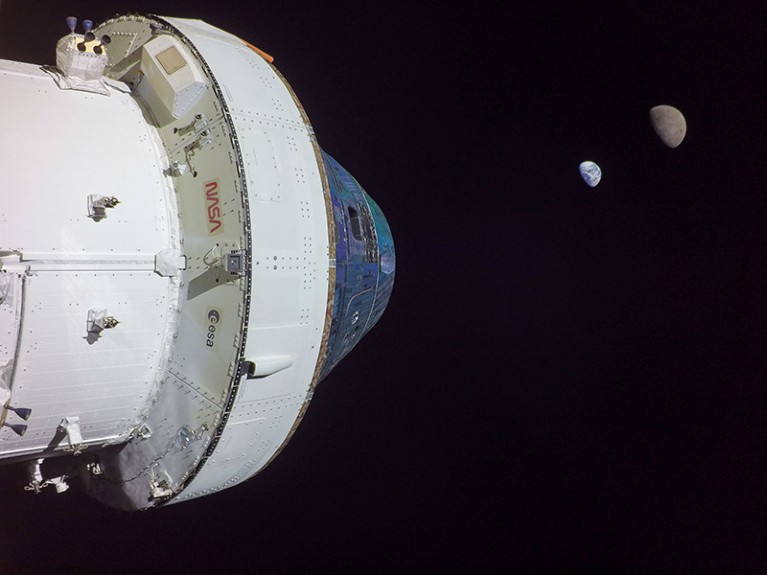

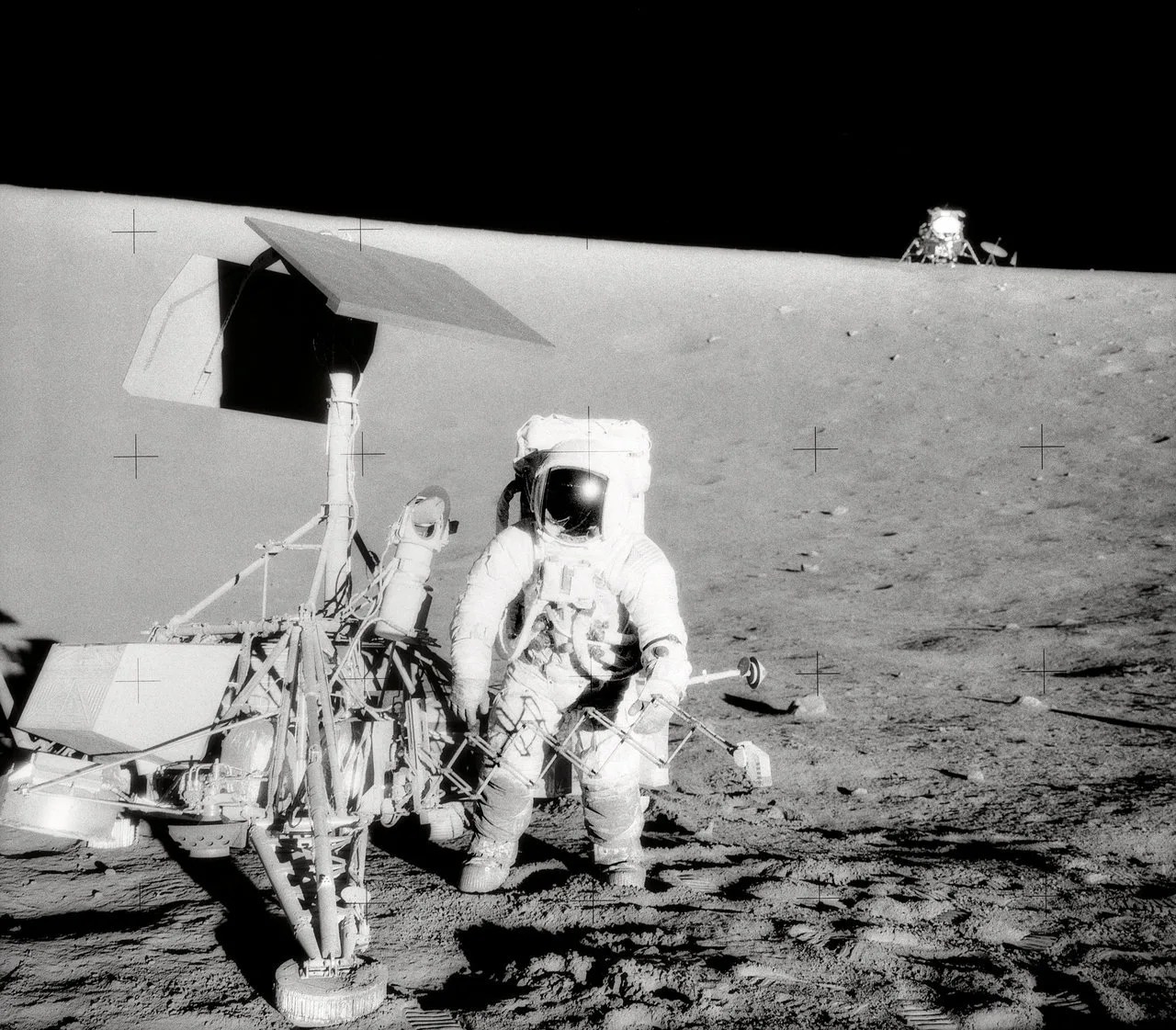

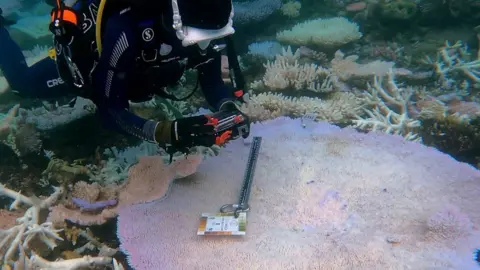

When the Apollo 17 astronauts splashed down successfully in the Pacific Ocean on December 19, 1972, it was the last time humans had visited the Moon. (Image courtesy of NASA)

The Space Shuttle finally orbited in 1981, after thin NASA budgets and challenging new technologies caused years of delay. With a new, space enthusiast president in office, Ronald Reagan, NASA leadership set about pushing what they had always believed was the “next logical step” to a sustainable space infrastructure, a space station. The shuttle had been sold to the Nixon administration as a way to make spaceflight much cheaper (a promise never fulfilled), but it was originally supposed to be a crew and cargo transport vehicle to a permanent space base. In late 1983, Reagan approved what eventually became the International Space Station (ISS).

It fell to his successor, George H.W. Bush, to propose sending humans back to the Moon and on to Mars. Bush spoke on the steps of our Museum on July 20, 1989: the 20th anniversary of Armstrong and Aldrin’s historic first Moonwalk. But his Space Exploration Initiative was short-lived. NASA’s 90-day study produced a politically toxic estimate of half a trillion dollars to establish a Moon base and land humans on Mars. Congress quickly lost interest.

As it was, the agency was preoccupied with keeping the shuttle flying after recovering from the Challenger disaster of 1986, while advancing a space station project already years late and billions over budget. The year 1990 saw major technical embarrassments, notably the discovery that the newly launched Hubble Space Telescope had a flawed mirror. Politicians and the media attacked NASA as bloated and bureaucratic, leading to cost overruns and failures. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War also undercut one of the civil space program’s key rationales. The space station came within one vote of being canceled in 1992 and was only politically safe after the Clinton administration merged it with the tottering Russian program to create the ISS in 1993-1994. Although the Cold War’s end ushered in an era of stagnant NASA budgets, it did have the ironic effect of saving the station, based on the argument that it would keep Russian rocket engineers from working for Iran, Iraq, or North Korea. Going back to the Moon was not on the agenda.

The next attempt came after the second shuttle disaster, that of Columbia in 2003. Criticisms of NASA, beyond those specific to the accident, focused on a human space program that seemed to have little direction beyond keeping the shuttle and ISS alive. In response, President George W. Bush announced the Vision for Space Exploration in early 2004. The shuttle would be phased out once the ISS was complete. NASA would create new vehicles to go back to the Moon and on to Mars. Then, as now, the agency argued that we needed to develop at the Moon the experience and technology necessary to go to the Red Planet. NASA created the Constellation Program, which was to put Americans on the Moon by the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11—2019. But it was predicated on the shuttle program ending sooner than it did, freeing up money. Constellation was underfunded and soon fell behind schedule, producing cost overruns. President Barack Obama canceled it soon after coming into office.

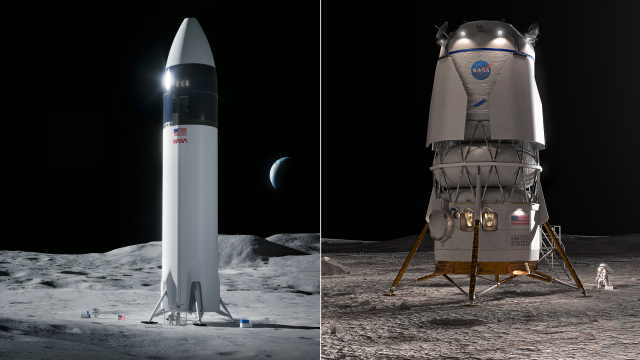

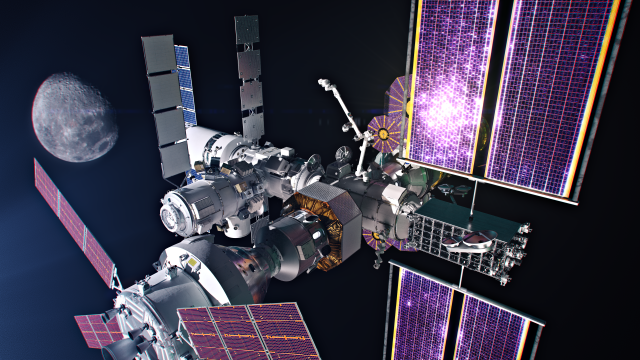

That leads us to the last, and in many ways, most unusual part of the story. Constellation’s cancellation did not actually kill the human lunar program. Democratic and Republican senators, particularly those from states with NASA centers or industries tied to the human space program, banded together. They funded a giant booster and a spacecraft based on Constellation designs and shuttle technologies. Thus the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and the Orion spacecraft emerged in the early 2010s. But they had no clear destination. Eventually, Congress directed NASA to build a small station in lunar orbit and develop the capability to land and create a Moon base. Under the Trump administration, the program got a name, Artemis (the sister of Apollo in Greek mythology), and a new objective: carry out a landing by 2024. While that date was never realistic, it put Artemis on a path that has continued under the Biden administration. After 50 years, the United States again has a sustained program to send astronauts back to the Moon.

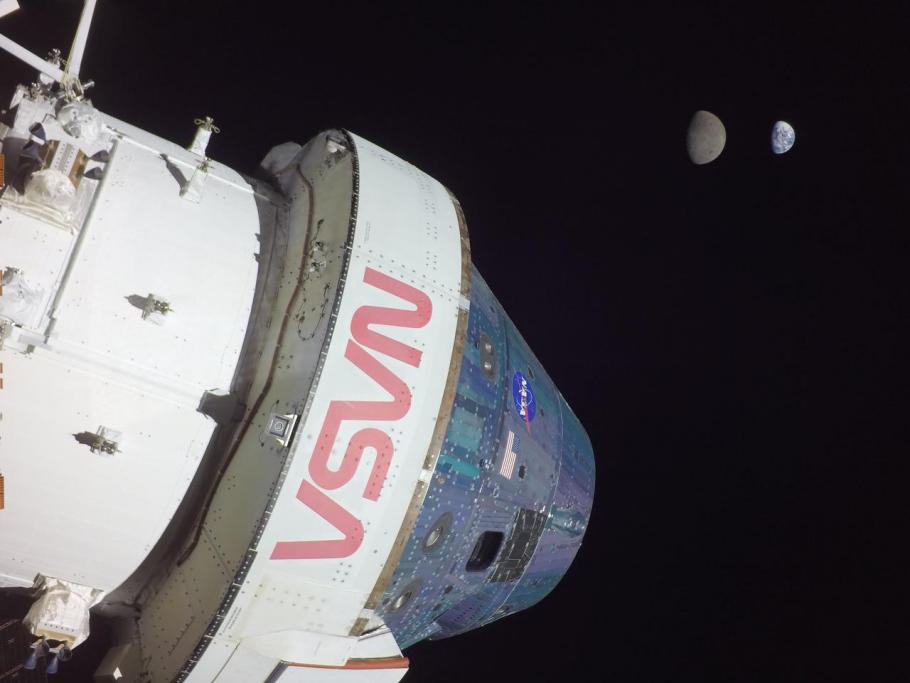

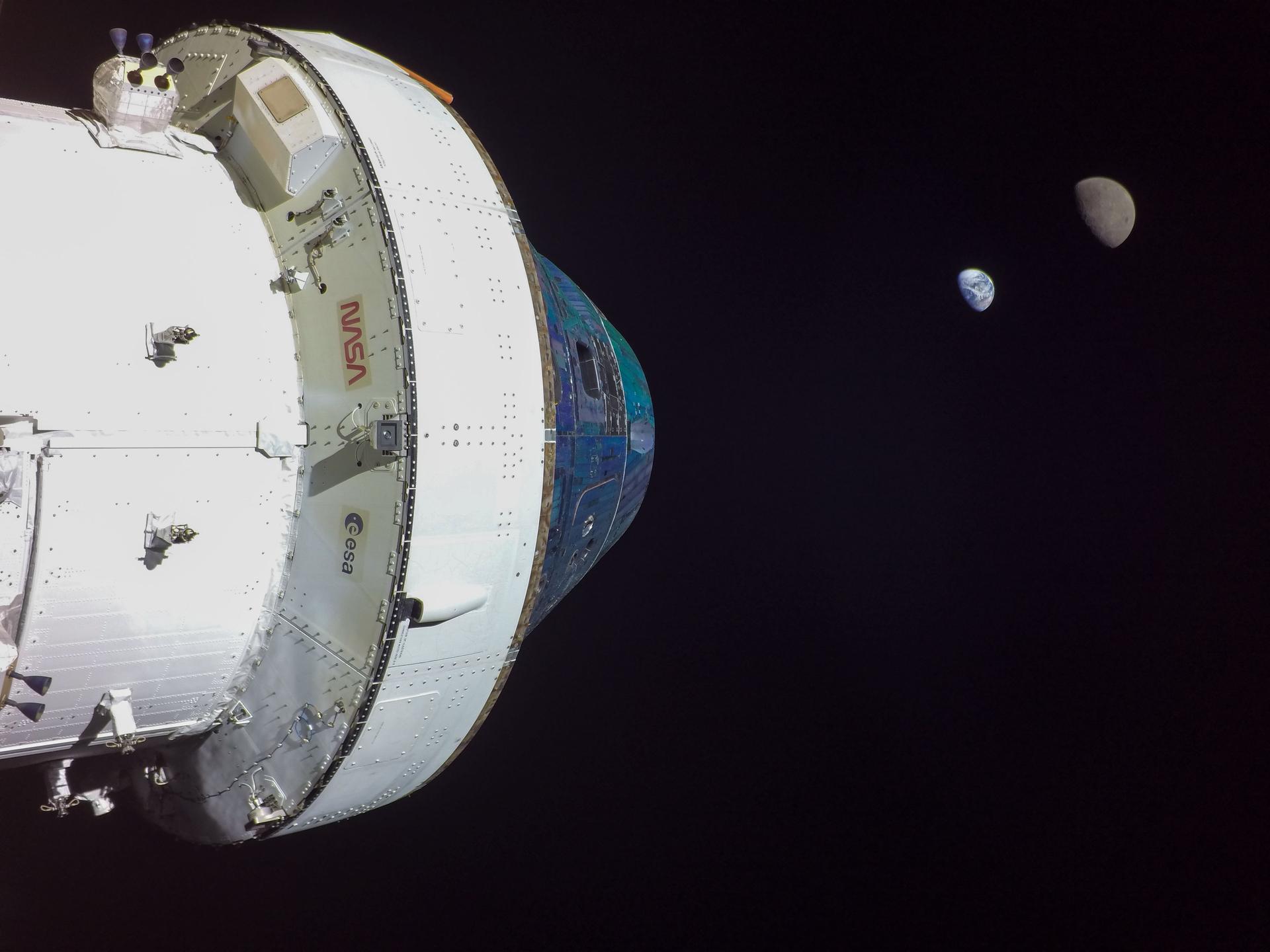

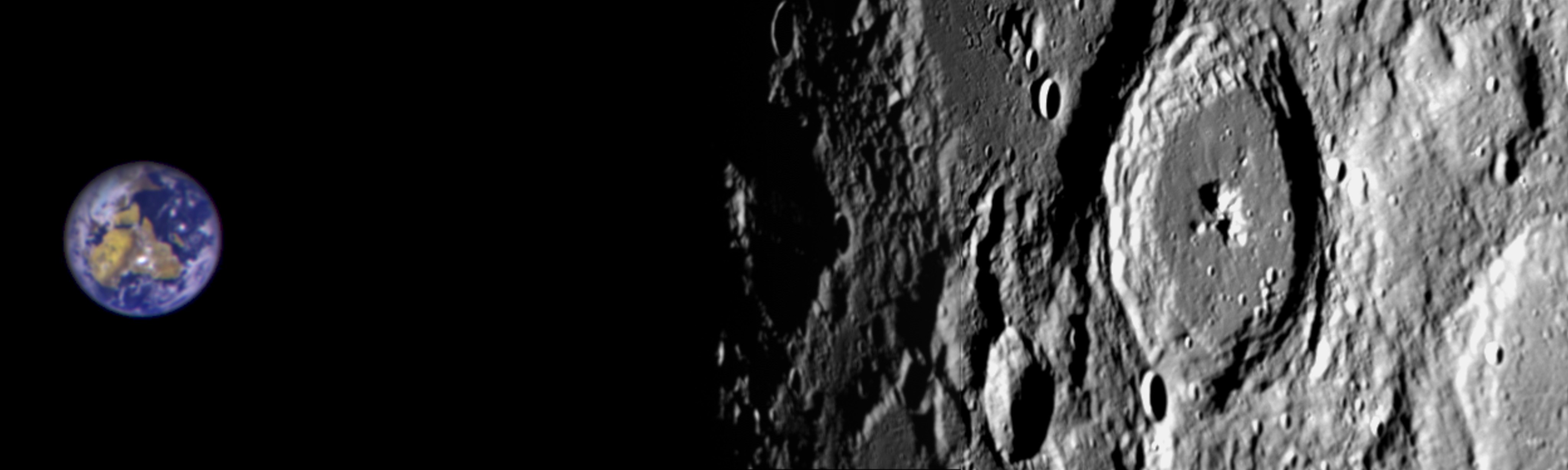

Project Artemis gives the United States a sustained program to send astronauts back to the Moon, after 50 years. (Image courtesy of NASA)

Why for over 40 years was there no such program and why has one emerged in the last decade? The answers are rooted in money, national prestige, and space program jobs. Apollo’s success undercut the logic of a program based primarily on Cold War competition; the failure of the Soviets to send any cosmonauts to the Moon only reinforced the disinterest in more missions. In an era of cutbacks, just building a presence in low Earth orbit became NASA’s only feasible human spaceflight program. The attempts of the two Bush presidencies to change that dynamic ran into a lack of support in the public and the political class for greatly increasing the agency’s budget.

What changed after 2010? The shuttle program’s end in 2011 freed up budget money but threatened massive layoffs in NASA centers and the aerospace industry. Congress wanted to sustain jobs in key states and felt that the human spaceflight program needed a higher purpose than just keeping ISS operational. Artemis has thus continued without a broad popular mandate or clear international competition, contradicting the pattern of the previous 40 years. China is mounting a space program that now includes robotic lunar and Mars probes, a permanent space station, and ambitions to build a Moon base. Competition with a foreign power may again become a major factor in the future, helping to sustain Artemis, but has not been critical so far.

The Orion spacecraft for the Artemis I mission successfully splashed down on December 11, 2022. (Image courtesy of NASA)

How will the American public react when astronauts go back to the Moon? Undoubtedly with excitement, just as there was in the 1960s. But what happens afterward? Will the public quickly lose interest, as it did after Apollo, and even if that happens, will it matter? Is there now a political base to keep Artemis in business at some level? Given the pattern of the last decade, I would say yes. Whatever happens, I look forward to humans once again traveling to the Moon in the next few years, whether on Artemis II or SpaceX’s Starship, both of which may fly there by 2025.

Michael J. Neufeld is a Senior Curator in the Space History Department and the lead curator of the "Destination Moon" gallery.

We rely on the generous support of donors, sponsors, members, and other benefactors to share the history and impact of aviation and spaceflight, educate the public, and inspire future generations. With your help, we can continue to preserve and safeguard the world’s most comprehensive collection of artifacts representing the great achievements of flight and space exploration.

- Get Involved

- Host an Event

Thank you. You have successfully signed up for our newsletter.

Error message, sorry, there was a problem. please ensure your details are valid and try again..

- Free Timed-Entry Passes Required

- Terms of Use

Astronauts explain why no human has visited the moon in 50 years — and the reasons are depressing

- The last time a person visited the moon was in December 1972, during NASA's Apollo 17 mission.

- Astronauts say the reasons are budgetary and political, not scientific or technical.

- NASA could land people on the moon again by 2026 at the earliest. Now a US lander is on the moon again.

Landing 12 people on the moon remains one of NASA's greatest achievements , if not the greatest.

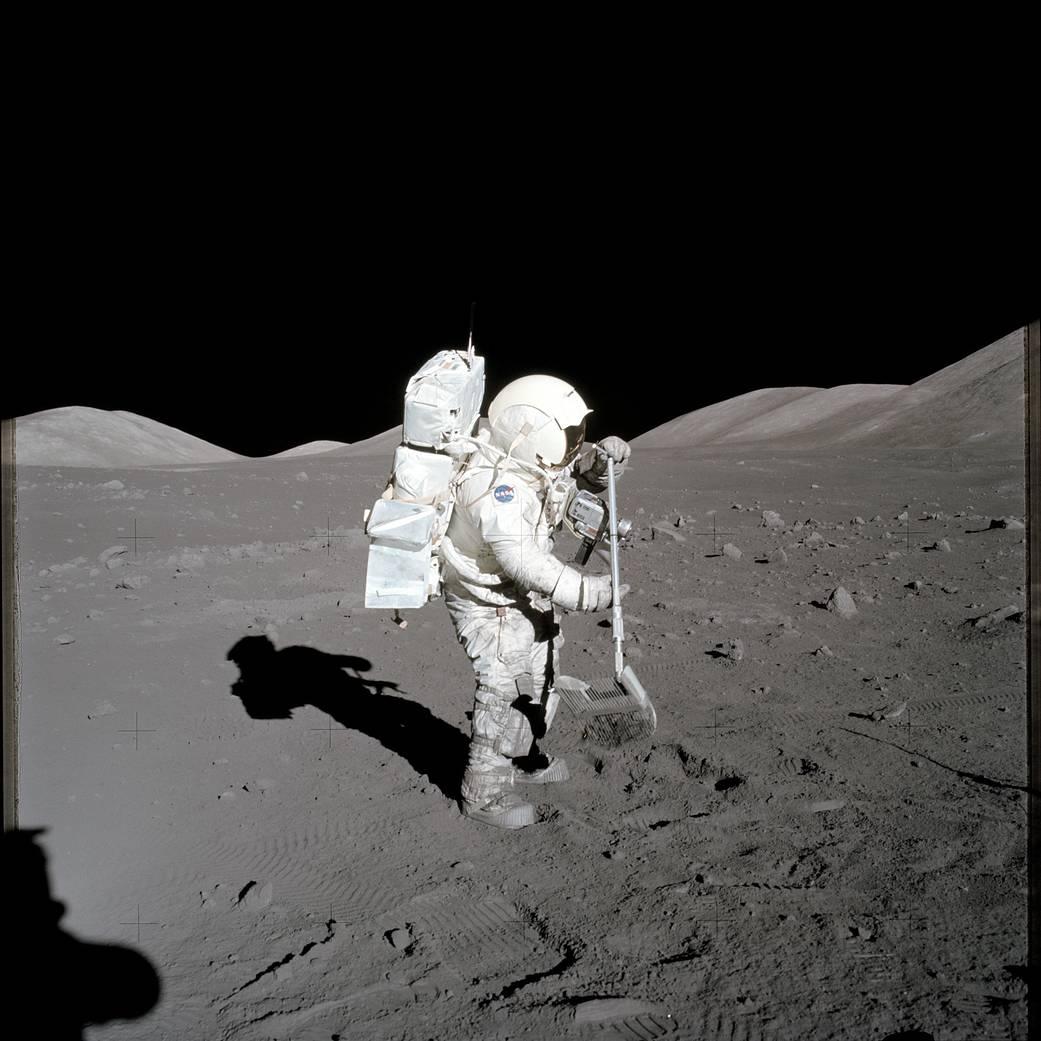

Astronauts on the Apollo missions of the 1960s and '70s collected rocks, took photos , performed experiments , planted flags , and then came home. But those stays didn't establish a lasting human presence on the moon.

More than 50 years after the most recent crewed moon landing — Apollo 17 in December 1972 — there are plenty of reasons to return people to Earth's giant, dusty satellite and stay there.

We're getting closer. On Thursday, a US lunar lander touched down on the moon's surface for the first time since Apollo 17. The uncrewed Nova-C lander, named Odysseus, was designed by the Houston company Intuitive Machines with a $118 million contract from NASA. It's the first commercial mission to touch down on the moon and a huge step toward new human landings.

NASA has promised we will see US astronauts on the moon again soon-ish — maybe by September 2026 at the earliest, in a program called Artemis , which is set to include the first woman, first Black astronaut, and first Canadian to touch the lunar surface.

Jim Bridenstine, who ran NASA during the Trump administration, said it's not science or technology hurdles that have held the US back from doing this sooner.

"If it wasn't for the political risk, we would be on the moon right now," Bridenstine said on a phone call with reporters in 2018. "In fact, we would probably be on Mars ."

So why haven't astronauts been back to the moon in more than 50 years?

"It was the political risks that prevented it from happening," Bridenstine said. "The program took too long and it costs too much money ."

Researchers and entrepreneurs have long pushed for the creation of a crewed base on the moon — a lunar space station.

"A permanent human research station on the moon is the next logical step. It's only three days away. We can afford to get it wrong and not kill everybody," Chris Hadfield, a former astronaut, previously told Business Insider. "And we have a whole bunch of stuff we have to invent and then test in order to learn before we can go deeper out."

A lunar base could evolve into a fuel depot for deep-space missions , lead to the creation of unprecedented space telescopes , make it easier to live on Mars , and solve long-standing scientific mysteries about Earth and the moon's creation . It could even spur a thriving off-world economy, perhaps one built around lunar space tourism .

But many astronauts and other experts suggest the biggest impediments to making new crewed moon missions a reality are banal and somewhat depressing.

It's really expensive to get to the moon — but not that expensive

A tried-and-true hurdle for any spaceflight program, especially missions that involve people, is the steep cost.

NASA's 2023 budget is $25.4 billion , and the Biden administration is asking Congress to boost that to $27.2 billion for 2024 .

Those amounts may sound like a windfall until you consider that the total gets split among all the agency's divisions and ambitious projects: the James Webb Space Telescope , the giant rocket project called Space Launch System , and far-flung missions to the sun , Jupiter , Mars , the asteroid belt , the Kuiper belt , and the edge of our solar system .

By contrast, the US defense budget for 2023 is about $858 billion .

With such a tight budget, NASA is vulnerable to government gridlocks. Congress has been slow to pass its 2024 budget — a delay NASA cited as a major reason for laying off 8% of its workforce at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in February.

Plus, NASA's budget is somewhat small relative to its past.

"NASA's portion of the federal budget peaked at 4% in 1965," Walter Cunningham, an Apollo 7 astronaut, said during congressional testimony in 2015.

In comparison, NASA's 2023 budget represents roughly 0.5% of US spending, according to a report from the Planetary Society . It has fluctuated between 0.4% and 1% since the 1970s, the report said.

Returning to the moon costs a significant chunk of that budget. A 2021 report from NASA estimated that the Artemis program to return people to the moon would cost a total of $93 billion from 2012 through 2025.

The Apollo program, by comparison, cost about $257 billion in today's dollars.

"Manned exploration is the most expensive space venture and, consequently, the most difficult for which to obtain political support," Cunningham said during his 2015 testimony.

He added, according to Scientific American : "Unless the country, which is Congress here, decided to put more money in it, this is just talk that we're doing here."

Referring to Mars missions and a return to the moon, Cunningham said, "NASA's budget is way too low to do all the things that we've talked about."

The problem with presidents

President Joe Biden may — or may not — be in office in 2026, when NASA plans to send astronauts back on the moon.

And therein lies another major problem: partisan political whiplash.

"Why would you believe what any president said about a prediction of something that was going to happen two administrations in the future?" Hadfield previously told Business Insider. "That's just talk."

The process of designing, engineering, and testing a spacecraft that could get people to another world easily outlasts a two-term president. But incoming presidents and lawmakers often scrap the previous leader's space-exploration priorities.

"I would like the next president to support a budget that allows us to accomplish the mission that we are asked to perform, whatever that mission may be," Scott Kelly, an astronaut who spent a year in space , wrote in a Reddit "Ask Me Anything" thread in January 2016, before Donald Trump took office.

But presidents and Congress don't often seem to care about staying the course.

In 2004, for example, the Bush administration tasked NASA to come up with a way to replace the space shuttle, which was set to retire, and also return to the moon. The agency came up with the Constellation program to land astronauts on the moon using a rocket called Ares and a spaceship called Orion.

NASA spent $9 billion over five years designing, building, and testing hardware for that human-spaceflight program.

Yet after President Barack Obama took office — and the Government Accountability Office released a report about NASA's inability to estimate a realistic cost for Constellation — Obama pushed to scrap the program and signed off on the SLS rocket instead.

Trump didn't scrap SLS, but he did change Obama's goal of launching astronauts to an asteroid , shifting priorities to moon and Mars missions. Trump wanted to see Artemis land astronauts back on the moon in 2024.

Such frequent changes to NASA's expensive priorities have led to cancellation after cancellation, a loss of about $20 billion , and years of wasted time and momentum.

Related stories

Biden seems to be a rare exception to the shifty presidential trend: He hasn't toyed with Trump's Artemis priority for NASA, and he's also kept the Space Force intact.

Buzz Aldrin said in testimony to Congress in 2015 that he believed the will to return to the moon must come from Capitol Hill.

"American leadership is inspiring the world by consistently doing what no other nation is capable of doing. We demonstrated that for a brief time 45 years ago. I do not believe we have done it since," Aldrin wrote in a statement . "I believe it begins with a bipartisan congressional and administration commitment to sustained leadership."

The real driving force behind that government commitment to return to the moon is the will of the American people, who vote for politicians and help shape their policy priorities. But public interest in lunar exploration has always been lukewarm .

Even at the height of the Apollo program, after Aldrin and Neil Armstrong stepped onto the lunar surface, only 53% of Americans said they thought the program was worth the cost. For the most part, US approval of Apollo hovered below 50%.

A 2023 Pew Research Poll found most Americans said NASA should continue leading space exploration. But that doesn't mean people care about going back to the moon — only 12% of the 10,329 respondents said NASA should prioritize human lunar missions.

Support for crewed Mars exploration isn't much stronger, with 11% of the poll's respondents saying it should be a NASA priority. Meanwhile, 60% said scanning the skies for killer asteroids was important.

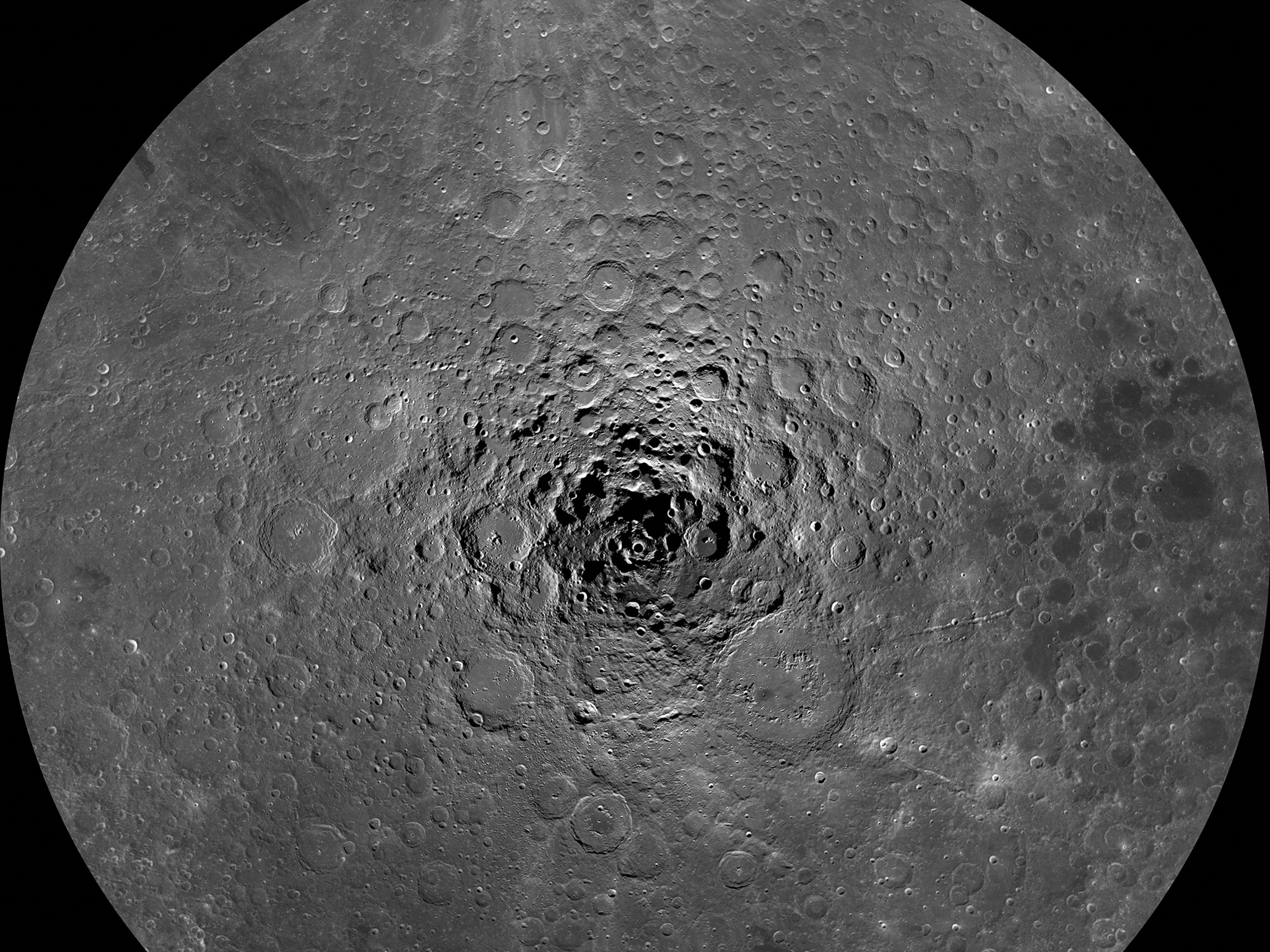

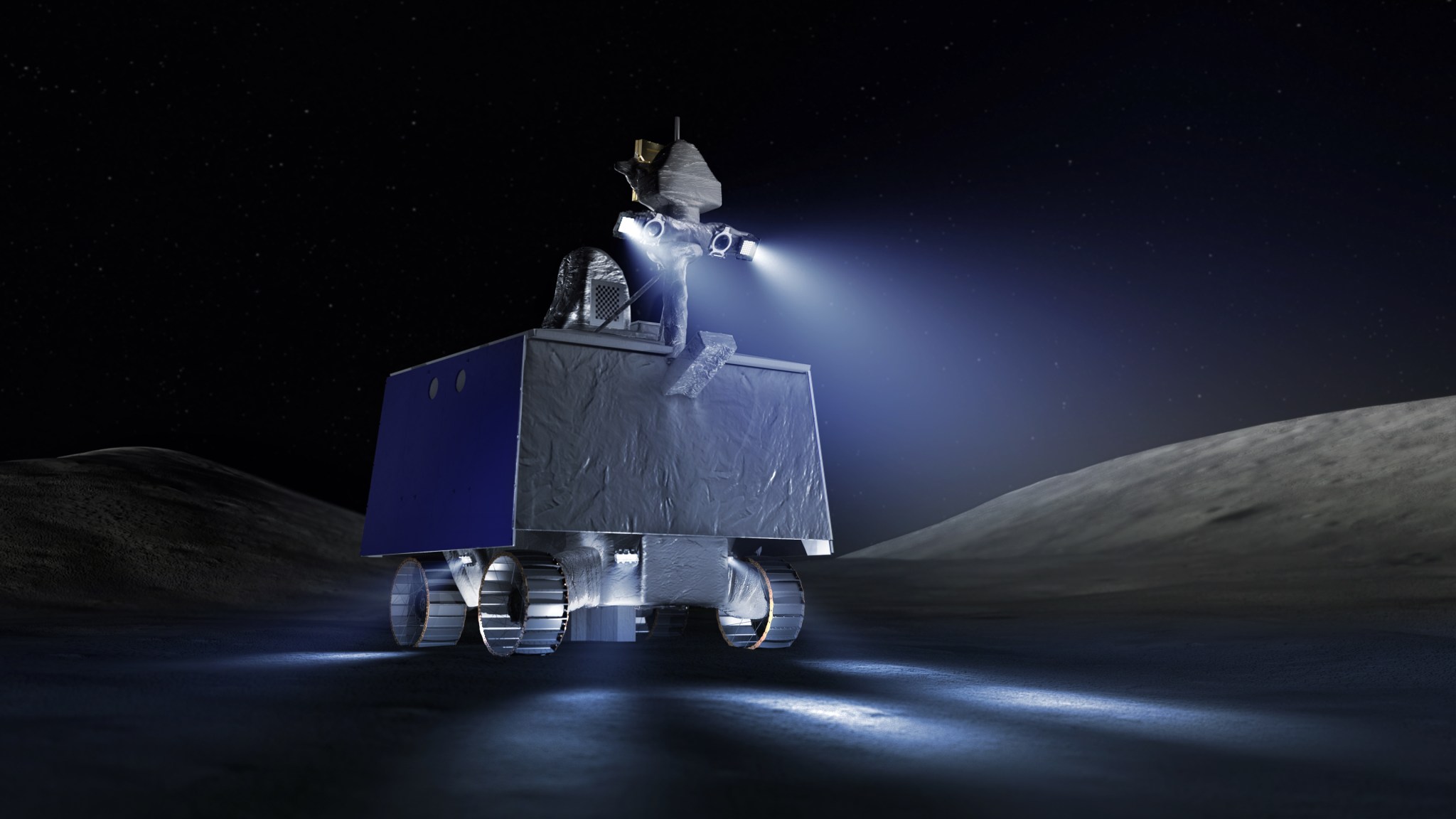

Many space enthusiasts have long hoped to build a base on the moon, but the lunar surface's harsh environment wouldn't be an ideal place for humans to thrive. NASA

The challenges beyond politics include problematic regolith and eye-popping temperature fluctuations.

The political tug-of-war over NASA's mission and budget isn't the only reason people haven't returned to the moon. The moon is also a 4.5-billion-year-old death trap for humans and must not be trifled with or underestimated.

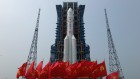

Its surface is littered with craters and boulders that threaten safe landings . The US government spent what would be tens of billions in today's dollars to develop, launch, and deliver satellites to the moon to map its surface and help mission planners scout for Apollo landing sites.

But a bigger worry is what eons of meteorite impacts have created: regolith, also called moon dust.

Following the Apollo missions, scientists quarantined the astronauts for two weeks after they landed, in part because they were worried about the effects of the dust, according to a 2022 NASA study . The fine powder that sits on the moon's surface stuck to their suits and vehicles and even got inside their spacecraft.

Peggy Whitson , an astronaut who has spent 675 days in space, previously told Business Insider that the Apollo missions "had a lot of problems with dust."

"If we're going to spend long durations and build permanent habitats, we have to figure out how to handle that," Whitson said.

An illustration of SpaceX's Starship vehicle on the surface of the moon, with Earth in the distance. Elon Musk/SpaceX via Twitter

There's also a problem with sunlight and deadly solar radiation .

For about 14 days at a time, the side of the moon facing Earth is a boiling hellscape that is exposed directly to the sun's harsh rays; the moon has very little atmosphere, and therefore no protection against solar radiation.

The next 14 days that same side is in total darkness, dipping to temperatures below minus 200 degrees Fahrenheit, making the moon's surface one of the colder places in the solar system.

NASA is developing a fission power system that could supply astronauts with electricity during weekslong lunar nights — which would also be useful on other worlds, including Mars.

"There is not a more environmentally unforgiving or harsher place to live than the moon," the astronautical engineer Madhu Thangavelu wrote. "And yet, since it is so close to the Earth, there is not a better place to learn how to live away from planet Earth."

NASA has designed dust- and sun-resistant spacesuits and rovers , though it's uncertain whether that equipment is anywhere near ready to launch.

"I already knew going to the moon was hard," Reid Weisman, the Artemis II mission commander, said at a press conference in August. "But boy, it's harder than I thought."

A generation of billionaire 'space nuts' may get there

Another issue, astronauts say, is NASA's graying workforce. In 2019, more American kids polled said they dreamed about becoming YouTube stars than astronauts .

"You've got to realize young people are essential to this kind of an effort," the Apollo 17 astronaut Harrison Schmitt previously told BI. "The average age of the people in Mission Control for Apollo 13 was 26 years old, and they'd already been on a bunch of missions."

An estimated 14% of NASA's workforce is over 40 years old, according to a Zippia analysis.

"That's not where innovation and excitement comes from. Excitement comes from when you've got teenagers and 20-year-olds running programs," Rusty Schweickart, a former NASA astronaut, said. "When Elon Musk lands a [rocket booster] , his whole company is yelling and screaming and jumping up and down."

Musk is part of what the astronaut Jeffrey Hoffman has called a "generation of billionaires who are space nuts," developing a new, private suite of moon-capable rockets .

"The innovation that's been going on over the last 10 years in spaceflight never would've happened if it was just NASA and Boeing and Lockheed," Hoffman told journalists during a roundtable in 2018. "Because there was no motivation to reduce the cost or change the way we do it."

Hoffman was referring to the innovative work of Musk's rocket company, SpaceX, as well as by Jeff Bezos, who founded the aerospace company Blue Origin.

"There's no question: If we're going to go farther, especially if we're going to go farther than the moon, we need new transportation," Hoffman added. "Right now we're still in the horse-and-buggy days of spaceflight."

Many astronauts' desire to return to the moon aligns with Bezos' long-term vision . Bezos has floated a plan to start building the first moon base using Blue Origin's New Glenn rocket system.

"We will move all heavy industry off of Earth, and Earth will be zoned residential and light industry," he said in April 2018 .

Musk has also spoken at length about how SpaceX's Starship launch system could pave the way for affordable, regular lunar visits.

"My dream would be that someday the moon would become part of the economic sphere of the Earth — just like geostationary orbit and low-Earth orbit," Hoffman said. "Space out as far as geostationary orbit is part of our everyday economy. Someday I think the moon will be, and that's something to work for."

SpaceX launched its complete Starship system for the first time in April.

But the rocket didn't make it to orbit as planned. Leaking propellant triggered fires in the booster, causing the system to veer off course, ultimately triggering the mega-rocket to self-destruct .

Even so, astronauts don't doubt whether we'll get back to the moon and onto Mars. It's just a matter of when .

"I guess eventually things will come to pass where they will go back to the moon and eventually go to Mars — probably not in my lifetime," said the 95-year-old retired astronaut Jim Lovell, who flew to the moon on Apollo 8 and Apollo 13. "Hopefully, they'll be successful."

This story was originally published on July 14, 2018. It has been updated.

Correction: February 27, 2024 — An earlier version of this story misstated the size of NASA's contract with Intuitive Machines. It was $118 million, not $118 billion. A prior version of this story also misstated the number of moonwalkers. During NASA's Apollo program, 12 people landed on the moon.

Watch: The first private company just landed on the moon. Here's how they did it.

- Main content

Why did we stop going to the Moon?

Why haven't we been back since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972?

In July 1969 humans landed on the Moon for the first time, as part of the Apollo 11 mission. But why haven't we been back since the Apollo 17 mission in 1972?

Why haven’t we been back to the Moon?

The Apollo 11 Moon landing in July 1969 was a huge feat of human endeavour, engineering and science. It was a moment that the world had been waiting for.

Apollo 11 was followed by six further trips to the Moon, five of which landed successfully. 12 men walked on the lunar surface in total. But in 1970 future Apollo missions were cancelled. Apollo 17 became the last crewed mission to the Moon, for an indefinite amount of time.

The main reason for this was money. The cost of getting to the Moon was, ironically, astronomical.

When was the last time we went to space?

Although we haven’t put a human on the lunar surface since the 1970s, there are now regular crewed missions to space.

Skylab - 1973-1974

Skylab was the first NASA managed and operated space station. It operated between May 1973 and Feb 1974. It had a workshop, an observatory and carried out hundreds of experiments.

Development and further use of Skylab was delayed due to problems developing the Space shuttle. Eventually the orbital decay of Skylab could not be stopped. Orbital decay is the gradual decrease of distance between two objects in orbit of each other.

Space Shuttle - 1981-2011

The first reusable spacecraft, NASA’s Space Shuttle enabled satellites to be launched and returned to Earth. The crewed spacecraft allowed NASA to travel to recover damaged satellites, fix them and send them back into space. The Space Shuttle was also instrumental in the development of the ISS.

Mir space station - 1986-2001

Mir was a Russian space station that was in operation from 1986 until 2001, and was the first continuously inhabited research station in orbit. Many experiments were carried out on the space station, and its success would become the blueprint for the current International Space Station.

International Space Station - 1998-present

The International Space Station, or ISS, is a continuously inhabited artificial satellite in low Earth orbit. A joint project between the USA, Russia, Japan, Europe and Canada, astronauts aboard the ISS carry out various experiments, and live on the station for about six months at a time.

When was the last time humans were on the Moon?

The last crewed mission to the Moon was Apollo 17, taking place between 7 and 19 December 1972. It was a 12-day mission and broke many records, the longest space walk, the longest lunar landing and the largest lunar samples brought back to Earth.

Harrison H. Schmitt was the lunar module pilot, as well as being a geologist. He was joined by Ronald E. Evans as command module pilot and Eugene Cernan as Mission Commander.

Space Race timeline

Apollo 17 was the only Apollo mission to not carry any astronauts who had previously been test pilots. After the cancellation of Apollo 18, the Apollo mission Schmitt had originally intended to go on, the scientific community lobbied that he be put onto Apollo 17.

Cernan was the last to leave the lunar surface, and therefore is the most recent person to stand on the Moon. As he ascended to the lunar module he said:

"...I'm on the surface; and, as I take man's last step from the surface, back home for some time to come - but we believe not too long into the future - I'd like to just [say] what I believe history will record. That America's challenge of today has forged man's destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17."

Whilst crewed missions to the moon have stopped, research into the moon and journeys to space still take place. There are also future plans for journeys to the Moon. NASA’s Artemis Programme aims to return to the Moon by 2024, and set up a sustained human presence that would allow us to regularly visit our celestial neighbour.

Find out more about the future of space travel

Why NASA stopped going to the moon

The race to land humans on the Moon was kickstarted by President John F. Kennedy’s 1962 speech at Rice Stadium in Houston, Texas, now known as the ‘We Choose to go to the Moon’ speech. In the speech, Kennedy committed to getting a human to walk on the Moon by the end of the decade:

"And this will be done in the decade of the 60s. It may be done while some of you are still here at school at this college and university. It will be done during the term of office of some of the people who sit here on this platform. But it will be done. And it will be done before the end of this decade."

When the Moon landing took place in 1969, Kennedy’s goal had been achieved, and his deadline met.

However, with the goal achieved NASA faced large funding cuts, making the future of the Apollo missions untenable. There had originally been 20 Apollo missions planned, but technological and research based missions were not seen as important as the achievement of the Moon landing itself, and the final three missions were cancelled.

Whilst the US government was willing to put a lot of money in to the Apollo missions when it was helpful to the space race, research and technological development were not viewed as a priority. Apollo 11 was a political statement in the midst of the space race, and once it had been made, the necessity for more missions to the Moon was gone.

Recent NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine highlighted this when he described the space race thus:

“This was a contest of political ideologies. It was a contest of economic ideologies. It was a contest of technological prowess. And in this great contest of great powers the United States of America was determined to win."

Going to the Moon was hugely expensive. Originally Kennedy’s government had estimated $7 billion dollars. In the end, the total cost was $20 billion dollars.

There was also less national support. The Apollo missions had all taken place against the backdrop of civil unrest in the US, and the large amounts of money being spent on space travel became a point of contention for the American public.

As the Cold War thawed, the Strategic Arms Limitations Talks (SALT) meant that missile production - including those used for space travel - was drastically reduced.

Future plans to go to the Moon are also driven by money. Whilst the Apollo missions saw astronauts live on the Moon for only a few days at a time, journeys to the moon in the 21st century would focus more on the creation of lunar bases or satellites. Bridensteine describes how the future of Lunar travel is about a sustained presence on the Moon.

"This time when we go to the Moon we're going to stay. That's what we're looking to do."

Never miss a shooting star

Sign up to our space newsletter for exclusive astronomy highlights, night sky guides and out-of-this-world events.

Visit the Royal Observatory

Fascinating books published by Royal Museums Greenwich on The Moon, and tools for astronomers

A brief history of moon exploration

In the 1950s, the Cold War sparked a race to visit Earth's moon with flybys, robots, and crewed missions. Here's what we discovered—and what's next.

For as long as humans have gazed skyward, the moon has been a focus of fascination. We could always see our cosmic partner’s mottled, cratered face by eye. Later, telescopes sharpened our views of its bumps, ridges, and relict lava seas. Finally, in the mid-20th century, humans visited Earth’s moon and saw its surface up close.

Since then, a volley of spacecraft have studied our nearest celestial neighbor, swooping low over its dusty plains and surveying its curious far side. Now, after six decades of exploration, we are once again aiming to send humans to the lunar surface.

Early forays into space

The earliest forays into lunar exploration were a product of the ongoing Cold War, when the U.S. and Soviet Union sent uncrewed spacecraft to orbit and land on the moon.

The Soviets scored an early victory in January 1959, when Luna 1 , a small Soviet sphere bristling with antennas, became the first spacecraft to escape Earth’s gravity and ultimately fly within about 4,000 miles of the moon’s surface. (Read more about early spaceflight.)

Later in 1959, Luna 2 became the first spacecraft to make contact with the moon's surface when it crashed in the Mare Imbrium basin near the Aristides, Archimedes, and Autolycus craters. That same year, a third Luna mission captured the first, blurry images of the far side of the moon—where the rugged highland terrain is markedly different from the smoother basins on the side closest to Earth.

Then, the U.S. got in the game with nine NASA Ranger spacecraft that launched between 1961 and 1965, and gave scientists the first close-up views of the moon’s surface. The Ranger missions were daring one-offs, with spacecraft engineered to streak toward the moon and capture as many images as possible before crashing onto its surface. By 1965, images from all the Ranger missions, particularly Ranger 9 , had revealed greater detail about the moon’s rough terrain and the potential challenges of finding a smooth landing site for humans.

In 1966, the Soviet spacecraft Luna 9 became the first vehicle to land safely on the lunar surface. Stocked with scientific and communications equipment, the small spacecraft photographed a ground-level lunar panorama. Later that year, Luna 10 launched, becoming the first spacecraft to successfully orbit the moon.

For Hungry Minds

NASA also landed a spacecraft on the moon’s surface that year with the first of its Surveyor space probes , which carried cameras to explore the moon's surface and soil samplers to analyze lunar rock and dirt. Over the two years that followed, NASA launched five Lunar Orbiter missions that were designed to circle the moon and chart its surface in preparation for the ultimate goal: landing astronauts on the surface. These orbiters photographed about 99 percent of the moon's surface, revealing potential landing sites and paving the way for a giant leap forward in space exploration. (See a map of all lunar landings.)

Humans on the moon

At the time, NASA was racing to fulfill a presidential promise: In 1961, President John F. Kennedy committed the United States to landing a person on the moon before the decade was complete. The Apollo program , by far the most expensive spaceflight endeavor in history , kicked off that year, and by the time it ended in 1972, nine missions and 24 astronauts had orbited or landed on the moon.

Perhaps the most famous of those, Apollo 11 , marked the first time humans had stepped on another world.

On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin touched down in the Sea of Tranquility in the lunar lander Eagle, while astronaut Michael Collins orbited the moon in the command module Columbia. Armstrong, who pressed the first bootprints into the moon’s surface, famously said , “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” The pair stayed on the moon’s surface for 21 hours and 36 minutes before rendezvousing with Collins and heading back to Earth. ( Exploring the legacy of Apollo 11 at the dawn of a new era of space travel. )

Each mission after Apollo 11 set new milestones in space travel and lunar exploration. Four months after the first humans reached the moon, Apollo 12 touched down, achieving a much more precise landing on the moon.

Apollo 13 narrowly avoided a near-disaster when on-board oxygen tanks exploded in April 1970, forcing the crew to abort a planned moon landing. All three survived.

During the third lunar landing, in January 1971, Apollo 14 , commander Alan Shepard set a new record for the farthest distance traveled on the moon: 9,000 feet. He even lobbed a few golf balls into a nearby crater with a makeshift 6-iron .

You May Also Like

The moon is even older than we thought

What’s out there? Why humanity keeps pushing the cosmic frontier.

U.S. returns to the moon as NASA's Odysseus successfully touches down

Apollo 15 , launched in July 1971, was the first of three missions capable of a longer stay on the moon. In the course of three days spent on the lunar surface, achievements included collecting hundreds of pounds of lunar samples and traveling more than 17 miles in the first piloted moon buggy. (The Soviet Union had sent a remotely controlled rover to the moon , Lunokhod 1, in 1970.)

Apollo 16 and Apollo 17 in 1972 were the two most recent crewed missions to the moon, and Russia’s Luna-24 crewless spacecraft in 1976 was the last to land until the following century. Samples collected during these lunar explorations produced huge amounts of knowledge about the geology and formation of the Earth’s moon . (See a timeline of the space race and its modern-day version in private spaceflight.)

After the dramatic accomplishments of the 1960s and 1970s, the major space agencies turned their attention elsewhere for several decades. So far, only 12 humans—all Americans and all men—have set foot on the moon.

Moon curiosity builds again

It wasn’t until 1994 that the moon came back into focus for the United States, with a joint mission between NASA and the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization. The Clementine spacecraft mapped the moon's surface in wavelengths other than visible light, from ultraviolet to infrared . Hiding in the more than 1.8 million digital photos it captured were hints of ice in some of the moon’s craters.

In 1999, the Lunar Prospector orbited the moon, confirming Clementine’s discovery of ice at the lunar poles, a resource that could be crucial for any long-term lunar settlement. The mission's end was spectacular: Prospector slammed into the moon, intending to create a plume that could be studied for evidence of water ice but none was observed. (Ten years later, NASA’s LCROSS spacecraft repeated this experiment and found evidence for water in a shadowed region near the moon’s south pole .)

Since 2009, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has taken high-resolution maps of the lunar surface. Between 2011 and 2012, it was joined in orbit by NASA’s twin GRAIL probes —named Ebb and Flow—which mapped the moon’s gravitational field before intentionally crashing into a region near the lunar north pole.

The recent—and future—status of moon exploration

NASA isn’t the only space agency with a surging interest in the moon. Within the last two decades, lunar exploration has gone truly international—and even commercial.

In 2007, Japan launched its first lunar orbiter, SELENE . China launched its first lunar spacecraft the same year, and India followed suit in 2008. By 2013, China became the third country to successfully land on the lunar surface, when its Chang’e-3 spacecraft deployed the Yutu rover.

More milestones—both for better and worse—were achieved in 2019. In January, another Chinese lander, Yutu-2, made history by becoming the first rover to touch down on the lunar farside . Meanwhile, India’s second lunar orbiter, Chandrayaan-2 , unsuccessfully deployed a small lander, Vikram , on the lunar surface that year. (India’s space agency hopes to try again in 2021 .) And in April 2019 Israel aimed for the moon with the launch of its Beresheet spacecraft . Unfortunately, even though the spacecraft achieved lunar orbit, it crashed during its attempt to land.

Unlike other spacecraft that came before it, Beresheet was built largely with private funding , heralding a new era of lunar exploration in which private companies are hoping to take the reins from governments.

NASA, for one, is partnering with commercial spaceflight companies to develop both robotic and crewed landers for lunar exploration; among those companies are SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Astrobotic. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos and Blue Origin have announced the goal of establishing a lunar base near the south pole where people could work and live. SpaceX is developing a spacecraft capable of ferrying astronauts to the moon and Mars , and is also developing a plan to bring tourists to lunar orbit. ( The future of spaceflight—from orbital vacations to humans on Mars .)

And not to be overshadowed by the commercial sector, NASA is planning its own ambitious return to the moon. The agency’s Artemis program, a sister to the venerable Apollo project, aims to put the first woman—and the next man— on the moon by 2024 . The backbone of Artemis is NASA’s Orion space capsule , currently in development, although the agency is also partnering with private companies to achieve its goal.

If Artemis goes well, then the near future might also see NASA and partners developing a space station in lunar orbit that could serve as a gateway to destinations on the moon’s surface—and beyond.

Related Topics

- SPACE EXPLORATION

- SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

- APOLLO MISSIONS

Why go back to the moon? NASA’s Artemis program has even bigger ambitions

Saturn’s ‘Death Star’ moon was hiding a secret: an underground ocean

Historic moon lander malfunctions after launch—but NASA isn’t panicked (yet)

Why did India land near the moon’s south pole?

Second SpaceX megarocket launch ends with another explosion. What happens next?

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Coronavirus Coverage

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Suggested Searches

- Climate Change

- Expedition 64

- Mars perseverance

- SpaceX Crew-2

- International Space Station

- View All Topics A-Z

Humans in Space

Earth & climate, the solar system, the universe, aeronautics, learning resources, news & events.

NASA’s Commercial Partners Deliver Cargo, Crew for Station Science

Hi-C Rocket Experiment Achieves Never-Before-Seen Look at Solar Flares

NASA Is Helping Protect Tigers, Jaguars, and Elephants. Here’s How.

- Search All NASA Missions

- A to Z List of Missions

- Upcoming Launches and Landings

- Spaceships and Rockets

- Communicating with Missions

- James Webb Space Telescope

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Why Go to Space

- Astronauts Home

- Commercial Space

- Destinations

- Living in Space

- Explore Earth Science

- Earth, Our Planet

- Earth Science in Action

- Earth Multimedia

- Earth Science Researchers

- Pluto & Dwarf Planets

- Asteroids, Comets & Meteors

- The Kuiper Belt

- The Oort Cloud

- Skywatching

- The Search for Life in the Universe

- Black Holes

- The Big Bang

- Dark Energy & Dark Matter

- Earth Science

- Planetary Science

- Astrophysics & Space Science

- The Sun & Heliophysics

- Biological & Physical Sciences

- Lunar Science

- Citizen Science

- Astromaterials

- Aeronautics Research

- Human Space Travel Research

- Science in the Air

- NASA Aircraft

- Flight Innovation

- Supersonic Flight

- Air Traffic Solutions

- Green Aviation Tech

- Drones & You

- Technology Transfer & Spinoffs

- Space Travel Technology

- Technology Living in Space

- Manufacturing and Materials

- Science Instruments

- For Kids and Students

- For Educators

- For Colleges and Universities

- For Professionals

- Science for Everyone

- Requests for Exhibits, Artifacts, or Speakers

- STEM Engagement at NASA

- NASA's Impacts

- Centers and Facilities

- Directorates

- Organizations

- People of NASA

- Internships

- Our History

- Doing Business with NASA

- Get Involved

- Aeronáutica

- Ciencias Terrestres

- Sistema Solar

- All NASA News

- Video Series on NASA+

- Newsletters

- Social Media

- Media Resources

- Upcoming Launches & Landings

- Virtual Events

- Sounds and Ringtones

- Interactives

- STEM Multimedia

Hubble Hunts Visible Light Sources of X-Rays

NASA Selects Students for Europa Clipper Intern Program

NASA Mission Strengthens 40-Year Friendship

NASA Selects Commercial Service Studies to Enable Mars Robotic Science

Two Small NASA Satellites Will Measure Soil Moisture, Volcanic Gases

NASA-Led Study Provides New Global Accounting of Earth’s Rivers

Orbits and Kepler’s Laws

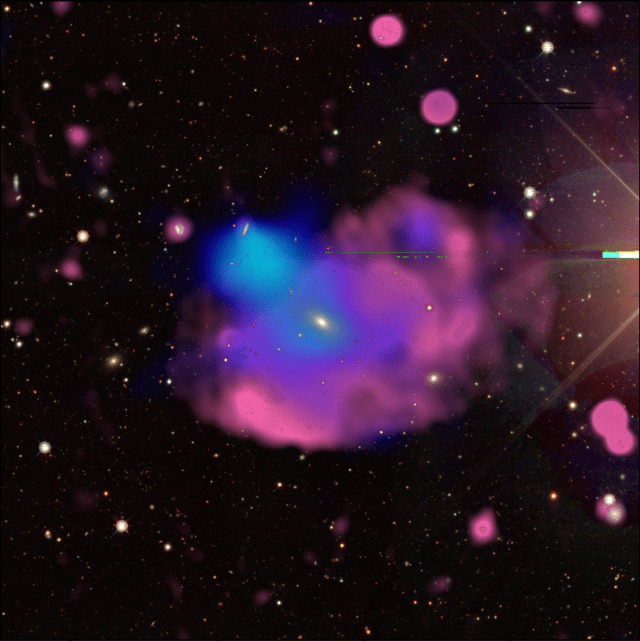

X-ray Satellite XMM-Newton Sees ‘Space Clover’ in a New Light

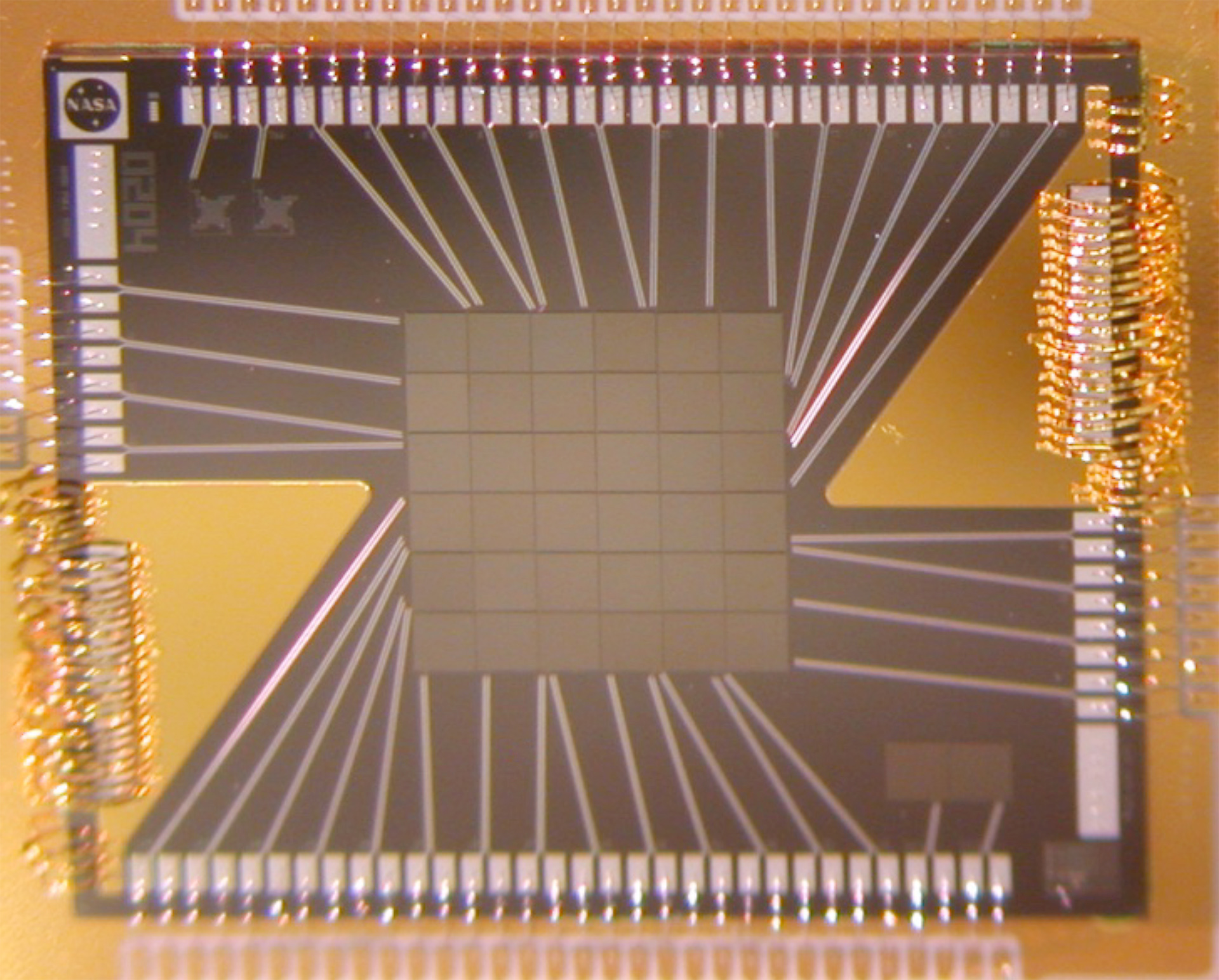

NASA/JAXA’s XRISM Mission Captures Unmatched Data With Just 36 Pixels

Researchers Develop ‘Founding Document’ on Synthetic Cell Development

ARMD Solicitations

NASA Uses Small Engine to Enhance Sustainable Jet Research

NASA Photographer Honored for Thrilling Inverted In-Flight Image

Big Science Drives Wallops’ Upgrades for NASA Suborbital Missions

Tech Today: Stay Safe with Battery Testing for Space

NASA Grant Brings Students at Underserved Institutions to the Stars

Washington State High Schooler Wins 2024 NASA Student Art Contest

Asian-American and Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander Heritage Month

Diez maneras en que los estudiantes pueden prepararse para ser astronautas

Astronauta de la NASA Marcos Berríos

Resultados científicos revolucionarios en la estación espacial de 2023

With the Artemis campaign, NASA will land the first woman and first person of color on the Moon, using innovative technologies to explore more of the lunar surface than ever before.

We will collaborate with commercial and international partners and establish the first long-term presence on the Moon. Then, we will use what we learn on and around the Moon to take the next giant leap: sending the first astronauts to Mars.

We’re going.

WHY WE’RE GOING TO THE MOON

We’re going back to the Moon for scientific discovery, economic benefits, and inspiration for a new generation of explorers: the Artemis Generation. While maintaining American leadership in exploration, we will build a global alliance and explore deep space for the benefit of all.

Science & Discovery

With Artemis, we’re building on more than 50 years of exploration experience to reignite America’s passion for discovery.

Economic Opportunity

Artemis missions enable a growing lunar economy by fueling new industries, supporting job growth, and furthering the demand for a skilled workforce.

Inspiration for a New Generation

We will explore more of the Moon than ever before with our commercial and international partners. Along the way, we will engage and inspire new audiences – we are the Artemis Generation.

Why the Moon

The Artemis missions will build a community on the Moon, driving a new lunar economy and inspiring a new generation. Narrator Drew Barrymore and NASA team members explain why returning to the Moon is the natural next step in human exploration, and how the lessons learned from Artemis will pave the way to Mars and beyond.

OUR SUCCESS WILL CHANGE THE WORLD

HOW WE ARE GOING TO THE MOON

We are developing a long-term strategy for lunar exploration that will allow our robots and astronauts to explore more and conduct more science than ever before.

Exploration Systems

Orion Spacecraft

The NASA spacecraft that will carry astronauts from Earth to lunar orbit and back.

Space Launch System Rocket

The only rocket that can send Orion, astronauts, and cargo to the Moon on a single mission. Upon launch, the Space Launch System will be the most powerful rocket in the world.

Exploration Ground Systems

The structures on the ground necessary to support launch and recovery of returning astronauts.

Human Landing System

Built by American companies, human landing systems are the final mode of transportation that will take astronauts from lunar orbit to the surface and back to orbit.

The spaceship in lunar orbit where astronauts will transfer between Orion and the lander on regular Artemis missions. Gateway will remain in orbit for more than a decade, providing a place to live and work, and supporting long-term science and human exploration on and around the Moon.

Surface Mobility

NASA is develop next-generation spacesuits, human-rated rovers, and spacewalking support systems to help astronauts traverse the lunar surface.

This is the Artemis Generation.

We go to the Moon for scientific discovery, economic benefits, and inspiration for a new generation of explorers: the Artemis Generation.

Artemis I was the first in a series of increasingly complex missions that will enable human exploration at the Moon and future missions to Mars.

Four astronauts will fly around the Moon to test NASA's foundational human deep space exploration capabilities, the Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft, for the first time with crew.

Artemis III: NASA’s First Human Mission to the Lunar South Pole

Humans have always been drawn to explore, discover, and learn as much as we can about the world—and worlds—around us.…

NASA’s Artemis IV: Building First Lunar Space Station

NASA and its partners are developing the foundational systems needed for long-term exploration at the Moon for the benefit of…

Living and Working at the Moon

As Artemis missions progress, NASA and its partners will continue to send exploration elements to the surface. Rovers will expand the exploration range and increase science return. Habitation elements will allow crews to stay on the surface for longer periods of time.

Join Artemis

Make, launch, teach, compete and learn. Find your favorite way to be part of the Artemis mission.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 12 December 2022

Fifty years after astronauts left the Moon, they are going back. Why?

- Alexandra Witze

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

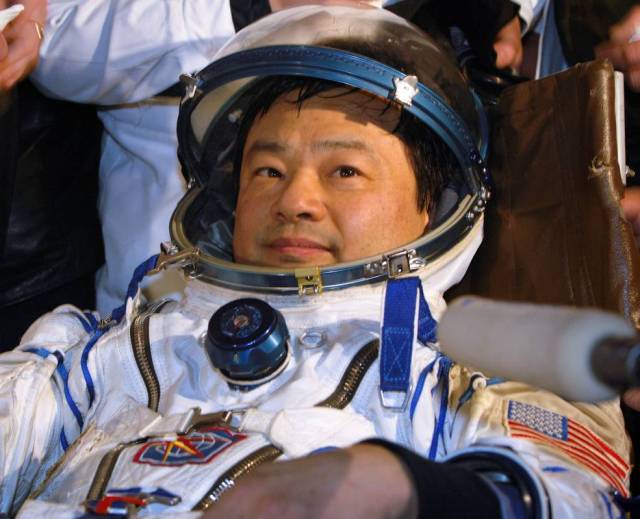

In 1972, three years after humans first reached the Moon, Apollo 17 commander Eugene Cernan was the last to leave it. Credit: NASA

As I take man’s last step from the surface, back home for some time to come — but we believe not too long into the future — I’d like to just say what I believe history will record: that America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus–Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind.

These words were spoken by Apollo 17 commander Eugene Cernan on 14 December 1972, as he prepared to return home from the Moon. With Neil Armstrong’s “one giant leap for mankind”, little more than three years earlier, they bookended a grand human endeavour. After 50 years, they remain the last (officially prepared) words spoken on the Moon.

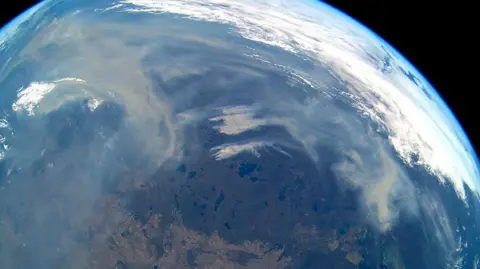

When Cernan, fellow Moon-walker Harrison Schmitt and command-module pilot Ronald Evans had blasted off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida seven days earlier, it was already clear that this would be the last Apollo mission. But few anticipated that, 50 years on, human exploration of space would be confined to low Earth orbit. Apollo 17 still marks the last time boots crunched into the soil of an alien world; the last time astronauts skipped joyously in the Moon’s low gravity; the last time anyone directly witnessed Earth’s blue globe rising above the grey lunar horizon.

The $93-billion plan to put astronauts back on the Moon

For most of the eight billion people now on Earth, the Apollo era is legend; the main significance of the photograph of a ‘blue marble’ Earth taken from Apollo 17 is as one of the default iPhone wallpapers. But with the launch last month of the Artemis I mission, NASA finally seems to be intent on rekindling the glory days of Apollo. Humanity is about to make a giant leap again. But to what end?

As Cernan and Schmitt guided their lunar module into the narrow Taurus–Littrow valley, each had a personal mission. Cernan was looking to gain the status of Moon-walker, which he had just missed in 1969 as lunar-module pilot on Apollo 10, the practice run for Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s successful landing with Apollo 11 a couple of months later.

Schmitt, meanwhile, was a geologist — still the only professional scientist to walk on the Moon. He had pushed NASA to continue the Apollo programme, arguing that humans could do better science than robot landers. The Moon’s ancient rocks, much less erased by tectonics than those of Earth, could hold the key to a new understanding of the Solar System.

Cernan and Schmitt spent 3 days in Taurus–Littrow, and more than 22 hours walking and driving around the valley’s landslides and volcanic cinder cones. They put more than 35 kilometres on the odometer of their lunar rover and picked up 110 kilograms of rocks to bring home, the biggest haul of any Apollo mission.

Then, late on 14 December, they parked the rover with its television camera pointing at the lander, to broadcast their departure. They left a plaque that read, in part, “Here man completed his first explorations of the moon, December 1972, A.D.”. After the greatest human voyage ever, deep-space exploration just — stopped.

Political drivers

The reasons lay, above all, in the shifting sands of politics. The Apollo programme was brought rousingly to life by US president John F. Kennedy’s “We choose to go to the Moon” speech in September 1962, when he promised that there would be US boots on the lunar soil by the end of the decade. It was a geopolitical prestige project, a response to the country falling behind in the cold war space race. In 1957, the Soviet Union had launched the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1. It had also put the first man into orbit — Yuri Gagarin in 1961, just the previous year.

But less than a year after the United States achieved the first successful Moon landing, the axe fell on Apollo. The demise was triggered when, in April 1970, an oxygen tank exploded two days after the launch of the Apollo 13 mission, threatening the lives of the astronauts on board. Missions after Apollo 17 were cancelled. But this was something of a pretext. Apollo was ruinously expensive, and by the late 1960s it was clear that the United States was comfortably ahead in the race. US president Richard Nixon, who took office in 1969, needed to do something with NASA that Kennedy had not.

The crew of Apollo 17, the last mission to land on the Moon, took this iconic photograph of Earth in 1972. Credit: NASA

Money and attention began to shift to low Earth orbit. NASA launched the Skylab space station in 1973, and fired the boosters on its space-shuttle programme. It aimed to establish a permanent human presence in space — but a few hundred kilometres up, not roughly 400,000 kilometres away on the Moon. Space became a rare symbol of cold war cooperation. In 1975, the United States and Soviet Union orchestrated a real and symbolic in-orbit handshake when an Apollo module docked with a Soyuz one and astronauts met cosmonauts. By 1998, with the launch of the International Space Station, the two had entered permanent cohabitation in space.

Nature special: 50 years since the Apollo Moon landing

And there, in low Earth orbit, things have stayed. Members of Congress have kept alive dreams of a US return to deep space by funnelling funds to their districts for aerospace jobs. But the momentum has never been fully regained. In 1989, on the 20th anniversary of Apollo 11, president George H. W. Bush announced an expensive push to return to the Moon and travel on to Mars. This ended four years later, the absence of a space race depriving it of great political support. In 2004, president George W. Bush tried again, with a more modest proposal for renewed lunar exploration. That came a year after the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated on re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere, killing its crew of seven and signalling the beginning of the end for the shuttle programme. This Bush plan got enough traction for NASA to begin building a new generation of Moon rockets — before president Barack Obama cancelled the programme in 2010, citing cost.

Then, the cycle was broken. In 2017, during Donald Trump’s presidency, Republican space-policy advisers crafted a fresh plan to return astronauts to the Moon. Jim Bridenstine, NASA’s administrator at the time, championed the programme and named it Artemis, after the ancient Greek goddess of the Moon, sister to the Sun god Apollo. For whatever reason, Joe Biden kept it on when he became president in 2021.

Science and strategy

To be sure, there are renewed scientific imperatives to return to the Moon. In the 1990s, researchers using orbiting spacecraft discovered frozen water on the lunar surface, showing that it was not bone-dry as once thought. That water could reveal secrets of the Solar System’s history – as well as being one thing we wouldn’t have to transport to a permanent lunar base.

But the sort of science that motivated Schmitt is the least of the reasons behind the renewed push. Technology and politics are again pertinent. Artemis is hugely expensive, projected to cost US$93 billion by 2025, but so far the costs are building slowly enough that members of Congress are allowing NASA small annual budget increases for it. The rise of powerful private companies such as Elon Musk’s SpaceX, based in Hawthorne, California, has brought new public enthusiasm for space exploration, as well as new ways of delivering it. NASA has contracted SpaceX to deliver Artemis astronauts to the lunar surface using the enormous Starship, with which Musk dreams of colonizing Mars.

The Orion capsule, shown during the Artemis I mission, could soon return people to the Moon. Credit: ESA/NASA

And then there is the looming influence of China, which has just finished building the main phase of its first space station and might be planning to land astronauts on the Moon in the 2030s. To the more hawkish members of the US Congress, sending astronauts to other worlds is once again a geopolitical statement. A not-insignificant reason for the revival of human space exploration is that it is once more being seen as a space race.

Some remain unconvinced that Artemis is fit for purpose. Critics such as Lori Garver, a former NASA deputy administrator, says the agency could move faster and more nimbly in its partnerships with aerospace companies. Many would prefer NASA to forget deep space and spend more time and money on Earth, including space-based climate monitoring. Such comments echo criticisms from the 1960s, when much of the US public wanted the government to focus not on the space race, but on Earth-bound problems such as civil rights.

Lift off! Artemis Moon rocket launch kicks off new era of human exploration

Despite those criticisms, the launch of the Artemis I mission on 16 November has given the programme a huge boost. NASA’s new Moon rocket — a Frankenstein’s creature cobbled together from previous rocket programmes, including the one started by George W. Bush — sent the as-yet uncrewed Orion capsule to orbit the Moon, to see how it would hold up in the hostile environment of deep space. The second Artemis mission should fly around the Moon no earlier than 2024, this time with astronauts on board. The third mission will land people on the Moon — including the first woman and the first person of colour.

What permanent significance that will have is anyone’s guess. But it does mean that, after half a century, we are finally recapturing some of the wonders of human space exploration. We are once again seeing live streams from lunar orbit — not from a robotic orbiter, but from a capsule that is steered remotely by humans and will one day carry them. We are seeing the pale blue dot of Earth, in the cold depths of interplanetary space, in real time, contextualizing our fragile presence on a vulnerable planet. These might be smaller steps for humankind than they once seemed — but they are steps, nevertheless.

Nature 612 , 397-399 (2022)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-04425-6

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Related Articles

- Planetary science

- Space physics

- Engineering

How to stop students cramming for exams? Send them to sea

News & Views 30 APR 24

Ancient DNA traces family lines and political shifts in the Avar empire

News & Views 24 APR 24

Network of large pedigrees reveals social practices of Avar communities

Article 24 APR 24

China's Chang'e-6 launches successfully — what happens next?

News 06 MAY 24

The science of 3 Body Problem: what’s fact and what’s fiction?

News Q&A 30 APR 24

What China’s mission to collect rocks from the Moon’s far side could reveal

News 30 APR 24

Total solar eclipse 2024: what dazzled scientists

News 10 APR 24

Total solar eclipse 2024: how it will help scientists to study the Sun

News 03 APR 24

‘Best view ever’: observatory will map Big Bang’s afterglow in new detail

News 22 MAR 24

Faculty Positions in Neurobiology, Westlake University

We seek exceptional candidates to lead vigorous independent research programs working in any area of neurobiology.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

School of Life Sciences, Westlake University

Seeking Global Talents, the International School of Medicine, Zhejiang University

Welcome to apply for all levels of professors based at the International School of Medicine, Zhejiang University.

Yiwu, Zhejiang, China

International School of Medicine, Zhejiang University

Assistant, Associate, or Full Professor

Athens, Georgia

University of Georgia

Associate Professor - Synthetic Biology

Position Summary We seek an Associate Professor in the department of Synthetic Biology (jcvi.org/research/synthetic-biology). We invite applicatio...

Rockville, Maryland

J. Craig Venter Institute

Associate or Senior Editor (microbial genetics, evolution, and epidemiology) Nature Communications

Job Title: Associate or Senior Editor (microbial genetics, evolution, and epidemiology), Nature Communications Locations: London, New York, Philade...

New York (US)

Springer Nature Ltd

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Missions to the moon: Past, present and future

The moon is a popular destination.

Moon mission FAQs

Nasa missions to the moon, international missions to the moon, expert q&a, additional resources, bibliography.

The moon is the closest major destination to Earth, so it's no surprise it's one of the most popular targets for space exploration missions.

NASA and numerous other countries have attempted to send missions to the moon , and even a few humans have made the journey.

The first generation of robotic moon explorers helped prepare for the Apollo moon landings, which sent a few American male astronauts to the surface between 1969 and 1972. Now NASA is leading a new consortium of international space agencies and companies for a new round of landings under the Artemis program . Meanwhile, numerous landers, rovers and other robotic explorers have sent back information about the moon.

Read more about notable moon missions below, and check out a full list of missions from The Planetary Society.

Related: Apollo landing sites: An observer's guide on how to spot them on the moon

How many missions to the moon have there been?

More than 140 missions launched to the moon. A small number of them had astronauts on board, but most of the missions were robotic orbiters, landers and rovers.

How many times have humans visited the moon?

Nine human missions were launched to the moon between 1968 and 1972, with some people flying on more than one mission. As for moonwalkers, 12 American male astronauts walked on the moon between 1968 and 1972.

Dozens of NASA missions have launched to the moon, but here are a few of the memorable ones:

Pioneer, Ranger, Surveyor, Lunar Orbiter missions

NASA's early moon explorers included several missions of the Pioneer, Ranger, Surveyor and Lunar Orbiter series. Given that they were quite early in space exploration, several of the mission attempts failed as engineers learned how to create spacecraft. Notable missions include Pioneer 4's lunar flyby in 1959, Ranger 7's deliberate impact on the moon in 1964, Surveyor 1's soft landing in 1966 and Lunar Orbiter's successful orbital insertion in 1966.

Apollo missions

NASA sent nine missions to the moon with humans on board between 1968 and 1972. Apollo 8 was the first to orbit the moon in December 1968. Apollo 10 did a simulated moon landing in May 1969, while Apollo 11 made the landing with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on board in July 1969. Apollos 12 through 17 brought people to the moon between 1969 and 1972. All landed astronauts with the exception of Apollo 13 , which suffered an explosion on the way in April 1970 and made a successful and safe abort back to Earth .

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has been mapping the moon in high definition since 2009. It has a global map of the moon that is continually updated as new craters and missions arrive. LRO has helped find reservoirs of water ice and is now serving as a pathfinder for future moon-landing missions, including those of the Artemis program.

Artemis human missions

NASA is preparing to send humans back to the moon with the Artemis program. The uncrewed Artemis 1 circled the moon in December 2022 with three mannequins, a clutch of tree seeds and numerous experiments, payloads and CubeSats. Artemis 2 is expected to go around the moon with a crew of four people in November 2024 or so, including three NASA astronauts ( Reid Wiseman , Christina Koch and Victor Glover ) and a Canadian astronaut ( Jeremy Hansen ). Artemis 3 will attempt a landing at the moon's south pole in 2025 or 2026 aboard a SpaceX Starship, with future missions following to the surface and the planned Gateway space station. Both SpaceX and Blue Origin are eligible to deliver human landers for future missions.

Artemis 1 cubesats

Artemis 1 launched 10 Artemis 1 cubesats built by a variety of entities. These satellites were considered experimental payloads. A few of them failed or experienced issues along the way, but they served as good demonstrators for how to operate tiny spacecraft far from Earth.

Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program

Several NASA-funded private missions received money under the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program that is aiming to bring rovers, landers and science experiments to the moon. CLPS will support the Artemis astronauts in their work on the surface.

Gateway and Capstone

NASA plans to launch a Gateway space station to the moon later in the 2020s using contributions from international partners that have signed on under the Artemis Accords . A cubesat mission known as Capstone is testing the unique orbit of Gateway ahead of time to ensure the path's stability. Should all go to plan, Gateway's orbit will see it swing close to the south pole to deliver astronauts and payloads, then far away on the opposite side.

Related: NASA's Gateway moon-orbiting space station explained in pictures

Many countries and companies have attempted moon missions over the last few decades. Here are a few of the memorable ones.

The Soviet Union

The Luna series made several flybys of the moon, starting in 1960. Zond 3, which flew by the moon's far side in 1965, and took photographs of a the largely unknown area. Zond 5 flew around the moon in 1968 with a "biological payload", including two small Steppe tortoises that survived the journey back to Earth. Luna 9 made the first soft touchdown on the lunar surface in 1966, while Luna 16 did the first robotic sample return in 1970. The first robotic lunar rover, Lunokhod 1, was deployed with Luna 17 in 1970; the successor Lunokhod 2 lasted even longer and drove 24 miles (39 kilometers) on the surface.

Other international moon missions

Japan launched its first mission (Clementine) in 1990, making it the third country to explore the moon. Other firsts included: Europe's SMART-1 in 2003, China's Chang'e-1 in 2007, India's Chandrayaan-1 in 2008, and Israel's Beresheet by private company Space IL that crashed upon landing in 2019. India's Chandrayaan-1 is also remembered for being the first mission to discover moon ice. China's Chang'e-3 delivered the Yutu rover to the near side of the moon in 2013, while Chang'e-4 and Yutu 2 together made the first lunar farside lander in 2019. (China wants to land humans on the moon independently at some point, too.) A private company from Japan, ispace, made an attempted moon landing in April 2023 that ended in an apparent crash .

Japanese billionaire and International Space Station tourist Yusaku Maezawa announced on Dec. 8, 2022, the eight artists (and two backups) he plans to take with him on a SpaceX Starship spacecraft to fly around the moon. A flight date has not yet been announced. The selected individuals include Tim Dodd, host and founder of the "Everyday Astronaut", a YouTube channel that covers space news.

Related: Artemis Accords: What are they & which countries are involved?

Bill Nelson is the 14th NASA administrator as of May 3, 2021, after decades of space advocacy in Congress. He chaired the space and science subcommittee in the U.S. House of Representatives for six years and the U.S. Senate for 12 years. He was also a ranking member of the full Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee. Nelson flew to space as a payload specialist aboard the space shuttle Columbia on the STS-61-C mission in January 1986, under a temporary initiative to bring spacefaring politicians to orbit.

Why are we going back to the moon?

We're going to live and learn and develop new technologies because we're eventually going to Mars . The goal was set by President Barack Obama. He gave a date, 2033, but it's more likely now that we'll see that landing on Mars late in the decade of the 2030s.

What makes Artemis different from Apollo?

This is the next step in that exploration, so this time we go with our international partners. Indeed, our international partners are many and you see on Artemis 1, for example, the European service module supporting operations on the Orion spacecraft .

Why is international cooperation on the moon important?

The Artemis Accords are setting the standards for how we're going to conduct ourselves in space. We do so at a difficult time on the face of the Earth and in Ukraine, where the aggressive Russian president Vladimir Putin has a war going on there. And yet, on the space station with our Russian partners, the professional relationship doesn't miss a beat.

This Q&A is based on a press conference with NASA on Aug. 27, 2022. It has been edited and condensed.

Read about all the missions to the moon at the Planetary Society . A huge table of moon missions is also available at NASA .

Canadian Space Agency. (2023, April 3). The Artemis Program: Humanity's return to the Moon. https://www.asc-csa.gc.ca/eng/astronomy/moon-exploration/artemis-missions.asp

European Space Agency. (n.d.) Artemis I. https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Human_and_Robotic_Exploration/Orion/Artemis_I

Lunar and Planetary Institute. (2023). Lunar Mission Summaries. https://www.lpi.usra.edu/lunar/missions/

NASA. (2023, April 18). Artemis Program. https://www.nasa.gov/artemisprogram

NASA. (2019, Feb. 1). The Apollo Missions. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/apollo/missions/index.html

SpaceX. (2023). The Moon: Returning Humans to Lunar Missions. https://www.spacex.com/human-spaceflight/moon/

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, " Why Am I Taller ?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace

Virgin Galactic to launch 7th commercial spaceflight on June 8

China launches Chang'e 6 sample-return mission to moon's far side (video)

Boeing Starliner rolls out to launch pad for 1st astronaut flight on May 6 (photos)

Most Popular

- 2 The history of the Jedi Order in 'Star Wars'

- 3 Star Wars Day 2024: 'Star Wars: Tales of the Empire' premieres today on Disney+

- 4 Free Comic Book Day 2024: Get Marvel Comics 'Star Wars #1' for free

- 5 This Week In Space podcast: Episode 109 — Music of the Spheres

NASA's Artemis II Astronauts Highlights From NASA’s Reveal of the Artemis II Moon Astronauts

The crew of three Americans and one Canadian will be the first humans to fly toward the moon in more than 50 years.

- Share full article

Kenneth Chang

NASA’s Artemis II astronauts reflect a wider swath of society.

HOUSTON — For the first time in more than half a century, NASA has named a crew of astronauts headed to the moon.

Humans have not ventured more than a few hundred miles off the planet since the return of Apollo 17, NASA’s last moon mission, in 1972. After Artemis’s experience on the moon, NASA hopes to chart a path to putting humans on Mars, while scientists expect to use what is found there to answer questions about how the solar system formed.

Astronauts in 2023 are much different from those when the United States was in a race to beat the Soviet Union to the moon. During the Apollo program, 24 astronauts flew to the moon, and 12 of them stepped on the surface. All of them were Americans. All of them were white men, many of whom were test pilots.

This time, the astronaut corps reflects a much wider swath of society.

They are Reid Wiseman, the mission’s commander; Victor Glover, the pilot; Christina Koch, mission specialist; and, Jeremy Hansen, also a mission specialist. The first three are NASA astronauts, while Mr. Hansen is a member of the Canadian Space Agency.

“When we were selecting astronauts back then,” Mr. Glover said in an interview, “we intended to select the same person, just multiple copies.”

Ms. Koch will be the first woman to venture beyond low-Earth orbit, and Mr. Hansen, as a Canadian, the first non-American to travel that far.

“So am I excited?” Ms. Koch said during an event unveiling the crew at Ellington Field, a small airport used by NASA for the training of astronauts. “Absolutely. But my real question is: are you excited?”

The assembled crowd cheered in response.