You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

- Buy Tickets

- Join & Give

When did modern humans get to Australia?

- Author(s) Fran Dorey

- Updated 09/12/21

- Read time 2 minutes

- Share this page:

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Linkedin

- Share via Email

- Print this page

Origins of the First Australians

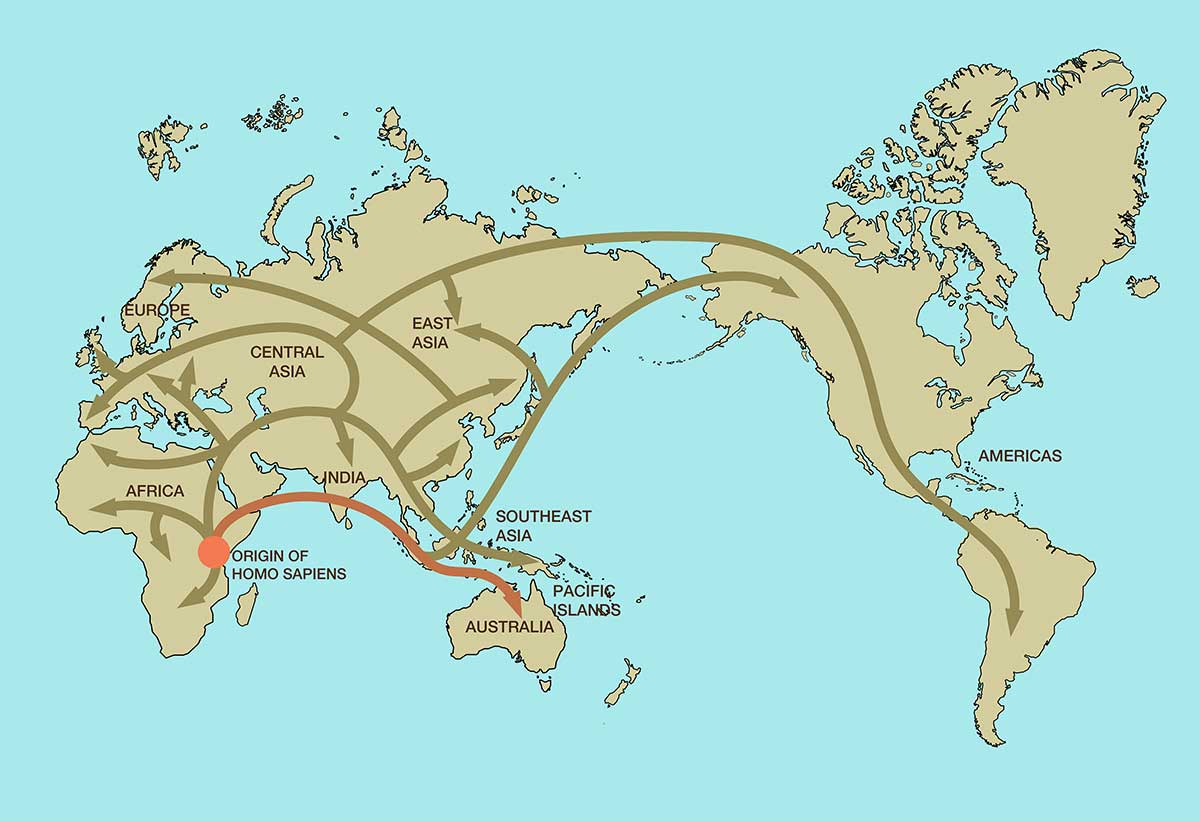

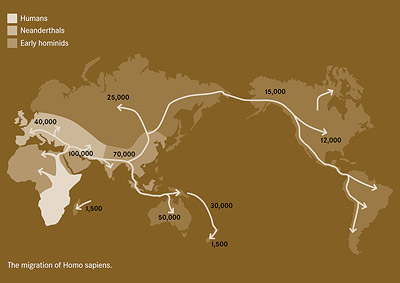

The viewpoints about the origins of these peoples was once entangled with the wider debate regarding the origins of all modern humans. During the 1980s and 1990s, the two main viewpoints were the ‘Out of Africa’ and ‘Multiregional’ models. However, new fossils and improved DNA research have resulted in these models becoming obsolete. The broad consensus now is that all modern humans are descended from an African population of Homo sapiens that migrated around the world but bred with local archaic populations as they did so.

There is some debate about the role that this interbreeding had in modern human origins. The ‘Recent African Origin’ model states that modern human traits merged in Africa and while interbreeding occurred during migrations around the world, these had only minimal impacts on genetic traits of modern humans. The ‘Assimilation’ model places greater emphasis on inter breeding, claiming that some Homo sapiens traits evolved in Africa, but many new traits evolved through interbreeding with other archaic populations outside of Africa.

‘Out of Africa’ stated that the first humans to colonise Australia came from a recent migration of Homo sapiens through South-east Asia. These people belonged to a single genetic lineage and were the descendants of a population that originated in Africa. The fossil evidence for the earliest Indigenous Australians does show a range of physical variation that would be expected in a single, geographically widespread population.

‘Multiregional’ proponents interpreted the variation found in the fossil record of early Indigenous Australians as evidence that Australia was colonised by two separate genetic lineages of modern humans. One lineage was believed to have been the evolutionary descendants of Indonesian Homo erectus while the other lineage had evolved from Chinese Homo erectus . Modern Aboriginal people are the result of the assimilation of these two genetic lineages.

The Asian Connection

Modern humans had reached Asia by 70,000 years ago before moving down through South-east Asia and into Australia. However, Homo sapiens were not the first people to inhabit this region. Homo erectus had already been in Asia for at least 1.5 million years. It is possible that these two species may have coexisted, as some dates for Indonesian Homo erectus suggest they may have survived there until as recently as 50,000 years ago. Homo erectus remains have never been found in Australia.

A second species, the Denisovans, was also know to inhabit this region and evidence shows they interbred with modern humans. Melanesians and Aboriginal Australians carry about 3-5 % of Denisovan DNA. This is explained by interbreeding of eastern Eurasian Denisovans with the modern human ancestors of these populations as they migrated towards Australia and Papua New Guinea.

Key fossil finds from Asia include

- ‘Solo Man’ - Homo erectus discovered in Ngangdong, Indonesia. ‘Solo Man’ shares similarities with earlier Homo erectus specimens from Sangiran and is considered to be a late Homo erectus . Its age is uncertain and, because its exact original location is unknown, published dates have ranged from 50,000 to 500,000 years old. If the younger age is correct, then it is possible that Homo erectus may have shared this region with Homo sapiens .

- ‘Wadjak’ - Homo sapiens d iscovered in 1889, Java, Indonesia. The age is between 8000 - 20,000 years old. Originally, this skull was thought to be about 50,000 years old and attempts were made to link this skull with the arrival of the first Australians. However, dating methods have been unable to determine exactly how old it is. It is now thought to be probably less than 20,000 years old.

- Zhoukoudian Upper Cave 101 - Homo sapiens discovered in 1933 in Zhoukoudian, China. Age is 10,000 - 25,000 years old.

Stay in the know

Uncover the secrets of the Australian Museum with our monthly emails.

Gateways into a new continent

There has always been an ocean separating Asia and Australia. At times this distance was reduced but the earliest travellers still had to navigate across large stretches of water.

For much of its history Australia was joined to New Guinea, forming a landmass called Sahul. These countries were finally separated by rising sea levels about 8,000 years ago. Genetic evidence supports the close ties between these two countries – the Indigenous peoples from these regions are more closely related to each other than to anyone else in the world, suggesting a recent common ancestry.

There are a number of likely paths of migration across Asia and into Sahul. These are based on the shortest possible route and take into consideration the land bridges that would appear during times of low sea levels. However, travel may have also occurred when sea levels were high. High sea levels would have reduced the amount of usable land and increased the population pressure. During these times it may have been necessary to expand into new areas.

Changing sea levels

Changing sea levels have significantly affected the geography of South-east Asia and Australia and the migration patterns of prehistoric peoples. During times of low sea levels the travelling distance between Timor and Sahul would have been reduced to about 90 kilometres.

Present sea levels are higher than they have been for most of the last million years. When water is locked up in the polar ice caps (known as an Ice Age) the sea level drops. When the climate becomes warmer, the ice melts and the sea level rises again.

The original seafarers

The settlement of Australia is the first unequivocal evidence of a major sea crossing and rates as one of the greatest achievements of early humans. However the motive and circumstances regarding the arrival of the first Australians is a matter for conjecture. It may have been a deliberate attempt to colonise new territory or an accident after being caught in monsoon winds.

The lack of preservation of any ancient boat means archaeologists will probably never know what kind of craft was used for the journey. None of the boats used by Aboriginal people in ancient times are suitable for major voyages. The most likely suggestion has been rafts made of bamboo, a material common in Asia.

The early occupation of Australia

The earliest dates for human occupation of Australia come from sites in the Northern Territory. The Madjedbebe (previously called Malakunanja II) rock shelter in Arnhem Land has a widely accepted date of about 50,000 years old. Reports of a date close to around 65,000 years old ( Nature , 2017), which was contentious at the time, have been rebutted by Allen & O'Connell in 2020. Molecular clock estimates, genetic studies and archaeological data all suggest the initial colonisation of Sahul and Australia by modern humans occurred around 48,000–50,000 years ago.

Over the last few decades, a significant number of archaeological sites dated at more than 30,000 years old have been discovered. By this time all of Australia, including the arid centre and Tasmania, was occupied. The drowning of many coastal sites by rising sea levels has destroyed what would have been the earliest occupation sites.

Recently published dates of 120,000 years ago for the site of Moyjil in Warrnambool, Victoria, offer intriguing, but unlikely, possibilities of much earlier occupation ( Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria , 2018). The site contains remains of shellfish, crabs and fish in what may be a ‘midden’, but definitive proof of human occupation is lacking and investigations are ongoing.

The First Australians

Much of our knowledge about the earliest people in Australia comes from archaeology. The physical remains of human activity that have survived in the archaeological record are largely stone tools, rock art and ochre, shell middens and charcoal deposits and human skeletal remains. These all provide information on the tremendous length and complexity of Australian Aboriginal culture.

Human Remains

The oldest human fossil remains found in Australia date to around 40,000 years ago – 20,000 years after the earliest archaeological evidence of human occupation. Nothing is known about the physical appearance of the first humans that entered the continent about 50,000 years ago. What is clear is that Aboriginal people living in Australia between 40,000 and 10,000 years ago had much larger bodies and more robust skeletons than they do today and showed a wide range of physical variation.

Stone tools

Stone tools in Australia, as in other parts of the world, changed and developed through time. Some early types, such as wasted blades, core tools, large flake scrapers and split pebble choppers continue to be made and used right up to today.

About 6000 years ago, new and specialised tools such as points, backed blades and thumbnail scrapers became common. Significant variation between the tool kits of different regions also appeared. Prototypes for this technology appeared earlier in Asia, suggesting this innovation was introduced into Australia.

The ground stone technique produces tools with a more durable and even edge, although not as sharp as a chipped tool. The oldest ground stone tools appear in Australia about 10,000 years before they appear in Europe, suggesting that early Australians were more technologically advanced in some of their tool manufacturing techniques than was traditionally thought.

Rock art, including painted and carved forms, plays a significant role in Aboriginal culture and has survived in the archaeological record for over 30,000 years. In age and abundance Australian Aboriginal rock art is comparable to world-renowned European cave sites such as those at Lascaux in France and Altamira in Spain.

It is probable that rock art was part of the culture of the first Australians. Its exact purpose is unknown but it is likely that from the earliest times rock art would have formed part of religious ritual activity, as is common in modern hunter-gatherer societies.

Ochre and mineral pigments

Mineral pigments, such as ochre, provide the oldest evidence for human arrival in Australia. Used pigments have been found in the earliest occupation levels of many sites, with some pieces dated at about 50,000 years old. This suggests that art was practised from the beginning of colonisation. Natural pigments were probably used for a range of purposes including burials, cave painting, decoration of objects and body art. Such usage still occurs today.

Ochre is an iron oxide found in a range of colours from yellow to red and brown. Red ochre is particularly important in many desert cultures due to the belief that it represents the blood of ancestral beings and can provide protection and strength. Ochre is used by grinding it into a powder and mixing it with a fluid, such as water, blood or saliva.

Living sites

Archaeological evidence for living sites of Ancient Aboriginal peoples comes in a variety of forms including fishing traps and weirs, stone-base huts, possible fireplaces and remains of meals and cooking activities. The evidence indicates that lifestyle practices varied across the continent and differed depending on climate, environment and natural resources.

Shell middens are the most obvious remains of meals and are useful because they provide insight into ancient Aboriginal diets and past environments and can also be radiocarbon dated to establish the age of a site.

Important Sites

Coobool Creek

The Coobool Creek collection consists of the remains of 126 individuals excavated from a sand ridge at Coobool Crossing, New South Wales, in 1950. After their excavation, they became part of the University of Melbourne collection until they were returned to the Aboriginal community for reburial in 1985.

The remains date from 9000 to 13,000 years old and are significant because of their large size when compared with Aboriginal people who appeared within the last 6000 years. They are physically similar to Kow Swamp people with whom they shared the cultural practice of artificial cranial deformation.

This ancient burial site in northern Victoria was excavated between 1968 and 1972. The human skeletons discovered here were extremely significant because they were accurately dated between 9500 to 14,000 years ago and demonstrated substantial differences between ancient and more recent Aboriginal people.

The remains of over forty individuals have been found at Kow Swamp and include those of men, women and children. This burial site is one of the largest from this time period anywhere in the world. Many of the skeletons have a greater skeletal mass, more robust jaw structures and larger areas of muscle attachment than in contemporary Aboriginal men. The female skeletons from this region also show similar differences when compared with modern Aboriginal women.

Key remains:

- ‘Kow Swamp 1’. Human skull rediscovered in 1967 in the National Museum of Victoria by Alan Thorne and Phillip Macumber. It is dated at 10,000 years old. The skull’s original burial location was traced through police reports, and excavations at Kow Swamp began soon after.

- 'Kow Swamp 5’. This 13,000-year-old skull is one of the better-preserved examples from Kow Swamp. It has a greater skeletal mass, a more robust jaw structure and larger areas of muscle attachment than in contemporary Aboriginal men.

- ‘Kow Swamp 14’. These remains were of a male skeleton with knees were drawn up under the chest with the hands in front of the face. In other Kow Swamp burials the skeleton was fully extended. It is not known why different burial positions were used.

The oldest human remains in Australia were found at Lake Mungo in south-west New South Wales, part of the Willandra Lakes system. This site has been occupied by Aboriginal people from at least 47,000 years ago to the present. This age range is supported by numerous geochronological ageing techniques including Radiocarbon (C14) determinations, Optically Stimulated Thermoluminesence (OSL) and Thermoluminesence (TL). Lake Mungo has been devoid of water for the last 18,000 years and is now a dry lakebed. In the past, lower evaporation and higher runoff from the Great Dividing Range allowed the lakes to fill, supporting plentiful freshwater resources such as fish and shellfish, and making the lakes a valuable source of food for the people that occupied the area.

- Mungo Woman, also referred to as ‘Lake Mungo 1’ (WLH 1), was discovered in 1968. At 42,000 years old, this is the most securely dated human burial in Australia and the earliest ritually cremated remains found anywhere in the world. The cremation process shrinks bone and has made the skeleton of this originally small-bodied woman even smaller. Dr Alan Thorne reconstructed the skull from over 300 fragments.

- Mungo Man, also known as 'Lake Mungo 3’ or (WLH 3) was discovered in 1974. Unlike Mungo Woman’s cremation, Mungo Man was laid out on his back for burial and covered in red ochre before being buried in the beach sands that bordered the lake. There has been some debate over the age of this burial and while dates ranging from 26,000 to 60,000 years old have been obtained, an age closer to 42,000 years old is widely accepted.

Mungo DNA In 2001, Australian scientists claimed that they had extracted mitochondrial DNA from ‘Mungo Man’ and nine other ancient Australians. They concluded that the genes of the modern-looking ‘Mungo Man’ were different from modern humans, proving that not all Homo sapiens have the same recent ancestor as stated in the ‘Out of Africa’ theory. These claims are controversial and could not be replicated in further studies in 2016 (PNAS 2016), and the only DNA that could be recovered from Mungo Man was European and certainly a contaminant.

Ancient DNA is easily contaminated and rarely survives for 30,000 years in conditions like those found in Australia. A complete mitochondrial genome from WLH 4, found several kilometres from Mungo Man, has been reconstructed. This individual was probably buried after the lakes had dried up in the Holocene (less than 10,000 years ago) and contains DNA that falls within the modern human range.

A skull was found in 1925 at Cohuna, north-west Kow Swamp, Victoria, and is undated. However, the similarity between this skull and the Kow Swamp people suggests they are both from a similar time period. This skull’s long, high, flat forehead reflects the characteristics of cranial deformation and its teeth and palate are larger than the current Australian average.

Evidence of human activity at Keilor dates back nearly 40,000 years. Stone flakes and charcoal deposits have been found in the lowest archaeological levels.

One of the key remains from this site was that of a 12,000 year old skull discovered in 1940. It is one of the earlier prehistoric Aboriginal remains found in Australia.

A cranium was discovered in 1884 on the Darling Downs, Queensland. It was the first Pleistocene human skull to be found in Australia. It is dated to between 9000 and 11,000 years old.

When it was found, the skull was covered in calcium carbonate, which gave the skull a deformed appearance. After cleaning, it was discovered that this skull belonged to a boy of about 15 years of age, who had died as a result of a blow to the side of the head. Features of the skull, such as the teeth and jaws, are remarkably large, but do fit within the range of variation of the Australian Aboriginal population.

One of many cultural practices that can alter the appearance of human skeletons is skull deformation. There is evidence that some Aboriginal groups did practise skull deformation in ancient times. Australian scientist Dr Peter Brown proposed that the ‘robust’ features seen in skulls such as ‘Cohuna’ and those from Kow Swamp and Coobool Creek are the result of such practices in the past. Prolonged pressing and binding of the head can produce characteristics such as long receding foreheads, flat frontal and occipital bones and lengthening of the skull.

Adcock, G. J., et al. (2001). "Mitochondrial DNA sequences in ancient Australians: Implications for modern human origins." Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 98 (2): 537-542.

Bowler, J. M., et al. (2003). "New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia." Nature 421 : 837-840.

Durband, A. C. R., Daniel R.; Westaway, Michael (2009). "A new test of the sex of the Lake Mungo 3 skeleton." Archaeology in Oceania 44 (2): 77-83.

Heupink, T. H. S., et. al. (2016). "Ancient mtDNA sequences from the First Australians revisited." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113 (25): 6892-6897.

Allen, O’Connell et al. (2020). "A different paradigm for the colonisation of Sahul", Archaeology in Oceania, Vol. 55 (2020): 182–191

The Australian Museum respects and acknowledges the Gadigal people as the First Peoples and Traditional Custodians of the land and waterways on which the Museum stands.

Image credit: gadigal yilimung (shield) made by Uncle Charles Chicka Madden

Human Arrival In Australia Pushed Back 18,000 Years

The new analysis of ancient tools also suggests that humans left Africa far earlier than thought.

We’ve long known that modern humans, or Homo sapiens, existed in Africa as far back as 200,000 years ago. Early humans in Australia were once thought to have arrived 47,000 years ago, signaling one of the later stops in the journey of human migration and one that would have required massive sea voyages.

A new discovery, recently published in the journal Nature, is challenging that, dating human arrival in Australia to 65,000 years ago, making Aboriginal Australian societies 18,000 years older than previously thought (although pending research on a rock shelter site could shift that downward closer to 10,000 years, if that pans out).

A team of archaeologists from the University of Queensland came to their conclusions by excavating a rock shelter in Majedbebe, a region in northern Australia, during digs conducted in 2012 and 2015. Among the artifacts found in the region were stone tools and hatchets, indicating an advanced understanding of weapon making. Similar hatches did not appear in other cultures for another 20,000 years, claimed the study’s authors.

"The axes were perfectly preserved, tucked up against the back wall of the shelter as we dug further and further," one of the study’s authors, Chris Clarkson, told Australia’s Fairfax Media .

Previous methods of dating artifacts relied on a technique called radiocarbon dating. However, the technique is only capable of providing accurate dates as far back as 45,000 years ago.

To reach their conclusion that humans arrived in Australia 65,000 years ago, the researchers used an additional technique called optically stimulated luminescence (OSL). The technique is applied to mineral grains and determines when it was last exposed to light, thus indicating to researchers how long an artifact has been buried.

The artifacts found by the archaeological team initially dated back only 10,000 years. As they dug further into the shelter, the found tools dating back 35,000, 40,000, and 65,000 years.

In order to reach Australia, Australia’s Aboriginal people would have had to undertake a nearly 60-mile voyage from surrounding regions. Clarkson also told the Sydney Morning Herald that it’s possible early Australians walked to the northern regions of the continent from Papau New Guinea when sea levels were significantly lower.

Chris Stringer, who wrote the book The Origin of Our Species and works as a researcher at the Natural History Museum in London, noted that human arrival in Australia marks a turning point in our evolution.

In an emailed statement to National Geographic, Stringer noted that the voyage necessary to arrive in Australia, “clearly demonstrates the high capabilities of the people who first accomplished it.”

Stringer also noted that pushing back the time period for human migration indicates that early humans may not have been in direct conflict with other hominids and animals to the extent previously thought. Earlier studies suggested human arrival in Australia corresponded with the extinction of multiple species. Human migration has also been attributed to the decline of Neanderthals .

To contextualize just how significant this 18,000-year extension is for understanding the history of Australia’s Aboriginal communities, the Sydney Morning Herald noted that, if Aboriginal culture was 24 hours old, white people have only been on the continent for five minutes .

The University of Queensland archaeology team was granted permission to dig in the region by the Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation. The Mirrar Aboriginal people retain the right to oversee all aspects of work on their land and retain a veto power.

FREE BONUS ISSUE

Related topics.

- PALEONTOLOGY

- ABORIGINALS

You May Also Like

Part Ape, Part Human

How Humans Are Shaping Our Own Evolution

Why Aboriginal Australians are still fighting for recognition

The 11 most astonishing scientific discoveries of 2023

A ‘kitten-otter-bear’? Untangling the identity of a very strange skeleton

- History & Culture

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Science & Environment

- History & Culture

- Opinion & Analysis

- Destinations

- Activity Central

- Creature Features

- Earth Heroes

- Survival Guides

- Travel with AG

- Travel Articles

- About the Australian Geographic Society

- AG Society News

- Sponsorship

- Fundraising

- Australian Geographic Society Expeditions

- Sponsorship news

- Our Country Immersive Experience

- AG Nature Photographer of the Year

- Web Stories

- Adventure Instagram

Home Topics History & Culture ‘Organised, technologically advanced’: first people to arrive in Australia came in large numbers, and on purpose

‘Organised, technologically advanced’: first people to arrive in Australia came in large numbers, and on purpose

IT TOOK MORE than 1,000 people to form a viable population. But this was no accidental migration, as our work shows the first arrivals must have been planned.

Our data suggest the ancestors of the Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, and Melanesian peoples first made it to Australia as part of an organised, technologically advanced migration to start a new life.

Changing coastlines

The continent of Australia that the first arrivals encountered wasn’t what we know as Australia today. Instead, New Guinea, mainland Australia, and Tasmania were joined and formed a mega-continent referred to as Sahul.

This mega-continent existed from before the time the first people arrived right up until about 8,000-10,000 years ago (try this interactive online tool to view the changes of Sahul’s coastline over the past 100,000 years).

When we talk about how and in what ways people first arrived in Australia, we really mean in Sahul.

We know people have been in Australia for a very long time — at least for the past 50,000 years, and possibly substantially longer than that .

We also know people ultimately came to Australia through the islands to the northwest. Many Aboriginal communities across northern Australia have strong oral histories of ancestral beings arriving from the north.

But how can we possibly infer what happened when people first arrived tens of millennia ago?

It turns out there are several ways we can look indirectly at:

- where people most likely entered Sahul from the island chains we now call Indonesia and Timor-Leste

- how many people were needed to enter Sahul to survive the rigours of their new environment.

First landfall

Our two new studies – published in Scientific Reports and Nature Ecology and Evolution – addressed these questions.

To do this, we developed demographic models (mathematical simulations) to see which island-hopping route these ancient people most likely took.

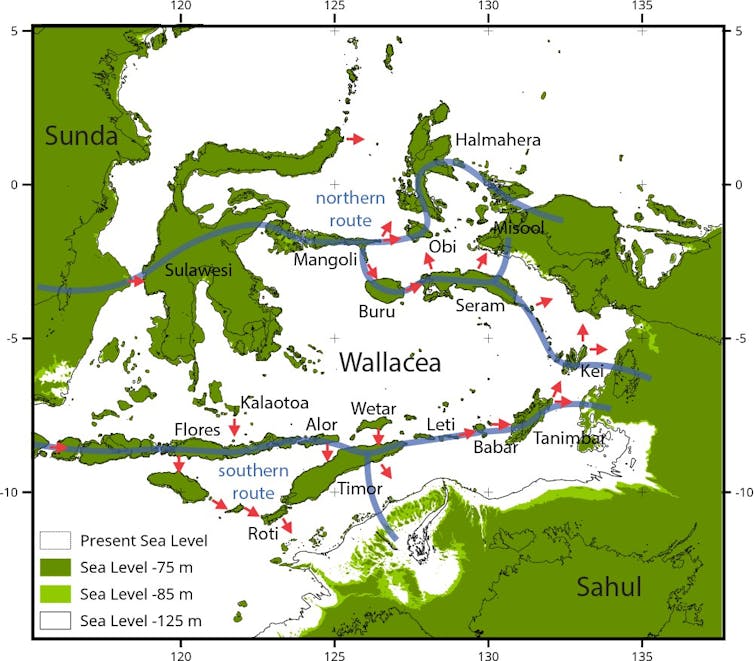

It turns out the northern route connecting the current-day islands of Mangoli , Buru , and Seram into Bird’s Head (West Papua) would probably have been easier to navigate than the southern route from Alor and Timor to the now-drowned Sahul Shelf off the modern-day Kimberley .

While the southern route via the Sahul Shelf is less likely, it would still have been possible.

Modelled routes for making landfall in Sahul. Sea levels are shown at -75 m and -85 m. Potential northern and southern routes indicated by blue lines. Red arrows indicate the directions of modelled crossings. (Image credit: Michael Bird)

Next, we extended these demographic models to work out how many people would have had to arrive to survive in a new island continent, and to estimate the number of people the landscape could support.

We applied a unique combination of:

- fertility, longevity, and survival data from hunter-gatherer societies around the globe

- “hindcasts” of past climatic conditions from general circulation models (very much like what we use to forecast future climate changes)

- well-established principles of population ecology.

Our simulations indicate at least 1,300 people likely arrived in a single migration event to Sahul, regardless of the route taken. Any fewer than that, and they probably would not have survived – for the same reasons that it is unlikely that an endangered species can recover from only a few remaining individuals.

Alternatively, the probability of survival was also large if people arrived in smaller, successive waves, averaging at least 130 people every 70 or so years over the course of about 700 years.

As sea levels rose, Australia was eventually cut off from New Guinea around 8,000 to 10,000 thousand years ago. (Image credit: Corey Bradshaw)

A planned arrival

Our data suggest that the peopling of Sahul could not have been an accident or random event. It was very much a planned and well-organised maritime migration.

Our results are similar to findings from several studies that also suggest this number of people is required to populate a new environment successfully, especially as people spread out of Africa and arrived in new regions around the world.

The overall implications of these results are fascinating. They verify that the first ancestors of Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, and Melanesian people to arrive in Sahul possessed sophisticated technological knowledge to build watercraft, and they were able to plan, navigate, and make complicated, open-ocean voyages to transport large numbers of people toward targeted destinations.

Our results also suggest that they did so by making many directed voyages, potentially over centuries, providing the beginnings of the complex, interconnected Indigenous societies that we see across the continent today.

Corey J. A. Bradshaw , Matthew Flinders Fellow in Global Ecology and Models Theme Leader for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Flinders University ; Laura S. Weyrich , ARC Future Fellow, Metagenomic Cluster Lead at the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, UoA Node Leader for the ARC Center of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, University of Adelaide ; Michael Bird , ARC Laureate Fellow, JCU Distinguished Professor, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, James Cook University , and Sean Ulm , Deputy Director, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

Why (most) Aussies love daylight saving

Daylight saving has 80 per cent support in Australia and a majority in every state.

Who invented the flat white?

Australia’s coffee culture – a source of great national pride – is usually associated with the wave of Greek and Italian migrants who settled in Melbourne and Sydney following the second world war. But it was very likely in regional Queensland that one of Australia’s favourite brews first took root.

Desert delight

The Great Victoria Desert, Australia’s largest, defies expectations. Visibly rich in biodiversity, it challenges preconceptions about how a desert should look.

Watch Latest Web Stories

Birds of Stewart Island / Rakiura

Endangered fairy-wrens survive Kimberley floods

Australia’s sleepiest species

2024 Calendars & Diaries - OUT NOW

Our much loved calendars and diaries are now available for 2024. Adorn your walls with beautiful artworks year round. Order today.

In stock now: Hansa Soft Toys and Puppets

From cuddly companions to realistic native Australian wildlife, the range also includes puppets that move and feel like real animals.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Humans First Arrived in Australia 65,000 Years Ago, Study Suggests

By Nicholas St. Fleur

- July 19, 2017

The timing of the first arrival of humans in Australia has been studied and debated for decades. Now, researchers have found evidence that suggests the ancestors of Aboriginal Australians landed in the northern part of Australia at least 65,000 years ago.

The finding, which was published Wednesday in the journal Nature , pushes back the timing of when people first came to the continent by about 5,000 to 18,000 years. It also suggests that humans coexisted with colossal Australian animals like giant wombats and wallabies long before the megafauna went extinct.

“This is the earliest reliable date for human occupation in Australia,” Peter Hiscock , an archaeologist at the University of Sydney who was not involved in the study, said in an email. “This is indeed a marvelous step forward in our exploration of the human past in Australia.”

Previous archaeological digs and dating had suggested people migrated to Australia between 47,000 and 60,000 years ago. But a new excavation at an aboriginal rock shelter called Madjedbebe revealed human relics that dated back 65,000 years.

“We were gobsmacked by the richness of material that we were finding at the site: fireplaces intact, a ring of grind stones around it, and there were human burials in their graves,” said Chris Clarkson , an archaeologist from the University of Queensland in Australia and lead author of the study. “No one dreamed of a site so rich and so old in Australia.”

The Madjedbebe site had been studied in the 1970s. But during more recent visits in 2012 and 2015, Dr. Clarkson and his colleagues recovered more than 11,000 artifacts from the deepest layers of the excavation pit. In addition to uncovering leftovers of an ancient campfire and archaic mortars and pestles, they also found flaked stone tools and painting material. They also unearthed the earliest known examples of edge-ground axes, which are stone axes that would have had handles, which were 20,000 years older than those found anywhere else in the world.

Dr. Clarkson said that the finding provides further insight into the complex capabilities of ancient humans as well as the chronology of when they migrated from Africa and spread across the world.

He also added that the findings provide evidence against a prevailing theory that people rapidly drove Australia’s largest animals to extinction shortly after arriving on the continent.

“It puts to bed the whole idea that humans wiped them out,” said Dr. Clarkson. “We’re talking 20,000 to 25,000 years of coexistence.”

To determine the age of the artifacts, the team had to date the sediment layer where they were buried. They first performed radiocarbon dating on sediment starting at the surface until they got to layers that were about 37,000 years old. They then shifted to a technique called optically stimulated luminescence dating for the deepest layers, which was used to measure the last time the sand in the rock shelter was exposed to sunlight.

Think of a grain of sand as an empty battery that slowly collects charge once it’s buried. As long as it remains in the dark it will continue gaining energy over time. If researchers can recover the grain of sand, and keep it dark, they can then use a laser to release the ‘charge’ within it. By measuring the amount of energy the grain of sand releases, and comparing that with the amount of radiation that the sand was exposed to while it was buried, researchers can determine when it was last in sunlight.

When it was dark, Zenobia Jacobs , a geochronologist from the University of Wollongong, and her colleagues used long tubes to bore into the sand layers where they found artifacts and collected 56 samples. Back at the lab she painstakingly measured more than 28,500 individual grains of sand and used a laser to determine their ages. After getting her results, the team sent several samples to independent labs to double check its work. The results came back verified.

“It was a great relief, I can tell you that,” said Dr. Jacobs.

She also helped confirm that the sand had not been significantly disturbed for tens of thousands of years. That meant that it could provide an accurate assessment for the age of the artifacts.

Jean-Luc Schwenninger , head of the Luminescence Dating Laboratory at the University of Oxford who was not involved in the study, said in an email that the team’s use of luminescence dating techniques provides a convincing case that humans came to Australia 65,000 years ago.

“However, the results of this thorough study also seem to suggest that this might be a rather conservative age estimate,” said Dr. Schwenninger, “and I would not at all be surprised if this date was pushed back even further in the future.”

Like the Science Times page on Facebook. | Sign up for the Science Times newsletter.

Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Humans first settled in australia as early as 65,000 years ago.

Artifacts reveal a people skilled with stone tools, other crafts

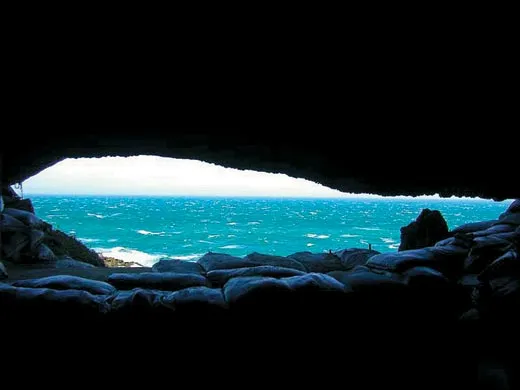

HOME SWEET HOME Artifacts found at the ancient rock-shelter known as Madjedbebe (shown) in northern Australia provide new insights into the lives of the first Australians.

Dominic O'Brien/Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation 2015

Share this:

By Maria Temming

July 19, 2017 at 1:00 pm

Tools, paints and other artifacts excavated from an ancient rock-shelter in northern Australia are giving new glimpses into early life Down Under. The first humans may have arrived on the continent 65,000 years ago — 5,000 years earlier than previously thought — and they were sophisticated craftspeople, researchers report July 19 in Nature .

Archaeologists unearthed three distinct layers of artifacts at Madjedbebe, Australia’s oldest known site of human habitation, during digs in 2012 and 2015. The oldest, deepest layer contained more than 10,000 relics of human handiwork. This cache included the world’s oldest polished ax heads, Australia’s oldest seed-grinding and pigment-processing tools, stone points that may have been spearheads, as well as hearths and other remnants of human activity.

“When people think about our ancient ancestors, they either tend to have a view that our ancestors must have been primitive, less culturally diverse, or they take the view that our ancestors were probably extraordinarily culturally impressive,” says Peter Hiscock, an archaeologist at the University of Sydney who was not involved in the study. “This indicates the latter view. The moment people get to Australia, they’re doing all this really smart stuff.” They were probably building fires to light nighttime activities, grinding seeds for food and using ochre paints to decorate cave walls or their own bodies, Hiscock says.

Previous estimates of the earliest human habitation of Australia — between 47,000 and 60,000 years ago — came from artifacts found at Madjedbebe in 1989. But archaeologists doubted those results because there were no detailed descriptions of the artifacts and it was unclear whether the artifacts were the same age as the surrounding sediment, says study coauthor Zenobia Jacobs, an archaeologist at the University of Wollongong in Australia.

Jacobs and colleagues estimated the ages of the newly uncovered artifacts by more precisely locating the artifacts underground and applying a method called optically stimulated luminescence dating, which reveals the last time a mineral grain was exposed to sunlight, to the sediment where the artifacts were found. Along with radiocarbon dating on charcoal remains from human-made fires, these analyses yielded a much more precise estimate for the age of sediments surrounding artifacts at various depths. The tests indicated that the deepest layer of artifacts — between about 2.15 and 2.6 meters below the surface — ranged in age from about 53,000 to 65,000 years.

Story continues after image

To say that humans first set foot in Australia exactly 65,000 years ago may be “a somewhat optimistic interpretation of the data,” Hiscock says. That’s because items buried in sand are liable to shift around a little. He suggests a more conservative estimate of human arrival between 55,000 and 60,000 years ago. Still, Hiscock says, that narrowed range is a major improvement over the wide, uncertain time span that archaeologists were working with before.

These new dates may provide insight into when humans migrated out of Africa ( SN: 12/24/16, p. 25 ). That in turn could help determine when humans interbred with archaic hominids on other continents — such as Neandertals in Europe and Denisovans in Asia — whose genes linger in the DNA of some modern people ( SN: 6/13/15, p. 11 ).

More Stories from Science News on Archaeology

Human brains found at archaeological sites are surprisingly well-preserved

These South American cave paintings reveal a surprisingly old tradition

This Stone Age wall may have led Eurasian reindeer to their doom

A four-holed piece of ivory provides a glimpse into ancient rope-making

Cold, dry snaps accompanied three plagues that struck the Roman Empire

An ancient, massive urban complex has been found in the Ecuadorian Amazon

How ancient herders rewrote northern Europeans’ genetic story

Here are some big-if-true scientific claims that made headlines in 2023

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

The Great Human Migration

Why humans left their African homeland 80,000 years ago to colonize the world

Guy Gugliotta

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/migrations_jul08_631.jpg)

Seventy-seven thousand years ago, a craftsman sat in a cave in a limestone cliff overlooking the rocky coast of what is now the Indian Ocean. It was a beautiful spot, a workshop with a glorious natural picture window, cooled by a sea breeze in summer, warmed by a small fire in winter. The sandy cliff top above was covered with a white-flowering shrub that one distant day would be known as blombos and give this place the name Blombos Cave.

The man picked up a piece of reddish brown stone about three inches long that he—or she, no one knows—had polished. With a stone point, he etched a geometric design in the flat surface—simple crosshatchings framed by two parallel lines with a third line down the middle.

Today the stone offers no clue to its original purpose. It could have been a religious object, an ornament or just an ancient doodle. But to see it is to immediately recognize it as something only a person could have made. Carving the stone was a very human thing to do.

The scratchings on this piece of red ocher mudstone are the oldest known example of an intricate design made by a human being. The ability to create and communicate using such symbols, says Christopher Henshilwood, leader of the team that discovered the stone, is "an unambiguous marker" of modern humans, one of the characteristics that separate us from any other species, living or extinct.

Henshilwood, an archaeologist at Norway's University of Bergen and the University of the Witwatersrand, in South Africa, found the carving on land owned by his grandfather, near the southern tip of the African continent. Over the years, he had identified and excavated nine sites on the property, none more than 6,500 years old, and was not at first interested in this cliffside cave a few miles from the South African town of Still Bay. What he would find there, however, would change the way scientists think about the evolution of modern humans and the factors that triggered perhaps the most important event in human prehistory, when Homo sapiens left their African homeland to colonize the world.

This great migration brought our species to a position of world dominance that it has never relinquished and signaled the extinction of whatever competitors remained—Neanderthals in Europe and Asia, some scattered pockets of Homo erectus in the Far East and, if scholars ultimately decide they are in fact a separate species, some diminutive people from the Indonesian island of Flores (see "Were 'Hobbits' Human?"). When the migration was complete, Homo sapiens was the last—and only—man standing.

Even today researchers argue about what separates modern humans from other, extinct hominids. Generally speaking, moderns tend to be a slimmer, taller breed: "gracile," in scientific parlance, rather than "robust," like the heavy-boned Neanderthals, their contemporaries for perhaps 15,000 years in ice age Eurasia. The modern and Neanderthal brains were about the same size, but their skulls were shaped differently: the newcomers' skulls were flatter in back than the Neanderthals', and they had prominent jaws and a straight forehead without heavy brow ridges. Lighter bodies may have meant that modern humans needed less food, giving them a competitive advantage during hard times.

The moderns' behaviors were also different. Neanderthals made tools, but they worked with chunky flakes struck from large stones. Modern humans' stone tools and weapons usually featured elongated, standardized, finely crafted blades. Both species hunted and killed the same large mammals, including deer, horses, bison and wild cattle. But moderns' sophisticated weaponry, such as throwing spears with a variety of carefully wrought stone, bone and antler tips, made them more successful. And the tools may have kept them relatively safe; fossil evidence shows Neanderthals suffered grievous injuries, such as gorings and bone breaks, probably from hunting at close quarters with short, stone-tipped pikes and stabbing spears. Both species had rituals—Neanderthals buried their dead—and both made ornaments and jewelry. But the moderns produced their artifacts with a frequency and expertise that Neanderthals never matched. And Neanderthals, as far as we know, had nothing like the etching at Blombos Cave, let alone the bone carvings, ivory flutes and, ultimately, the mesmerizing cave paintings and rock art that modern humans left as snapshots of their world.

When the study of human origins intensified in the 20th century, two main theories emerged to explain the archaeological and fossil record: one, known as the multi-regional hypothesis, suggested that a species of human ancestor dispersed throughout the globe, and modern humans evolved from this predecessor in several different locations. The other, out-of-Africa theory, held that modern humans evolved in Africa for many thousands of years before they spread throughout the rest of the world.

In the 1980s, new tools completely changed the kinds of questions that scientists could answer about the past. By analyzing DNA in living human populations, geneticists could trace lineages backward in time. These analyses have provided key support for the out-of-Africa theory. Homo sapiens , this new evidence has repeatedly shown, evolved in Africa, probably around 200,000 years ago.

The first DNA studies of human evolution didn't use the DNA in a cell's nucleus—chromosomes inherited from both father and mother—but a shorter strand of DNA contained in the mitochondria, which are energy-producing structures inside most cells. Mitochondrial DNA is inherited only from the mother. Conveniently for scientists, mitochondrial DNA has a relatively high mutation rate, and mutations are carried along in subsequent generations. By comparing mutations in mitochondrial DNA among today's populations, and making assumptions about how frequently they occurred, scientists can walk the genetic code backward through generations, combining lineages in ever larger, earlier branches until they reach the evolutionary trunk.

At that point in human history, which scientists have calculated to be about 200,000 years ago, a woman existed whose mitochondrial DNA was the source of the mitochondrial DNA in every person alive today. That is, all of us are her descendants. Scientists call her "Eve." This is something of a misnomer, for Eve was neither the first modern human nor the only woman alive 200,000 years ago. But she did live at a time when the modern human population was small—about 10,000 people, according to one estimate. She is the only woman from that time to have an unbroken lineage of daughters, though she is neither our only ancestor nor our oldest ancestor. She is, instead, simply our "most recent common ancestor," at least when it comes to mitochondria. And Eve, mitochondrial DNA backtracking showed, lived in Africa.

Subsequent, more sophisticated analyses using DNA from the nucleus of cells have confirmed these findings, most recently in a study this year comparing nuclear DNA from 938 people from 51 parts of the world. This research, the most comprehensive to date, traced our common ancestor to Africa and clarified the ancestries of several populations in Europe and the Middle East.

While DNA studies have revolutionized the field of paleoanthropology, the story "is not as straightforward as people think," says University of Pennsylvania geneticist Sarah A. Tishkoff. If the rates of mutation, which are largely inferred, are not accurate, the migration timetable could be off by thousands of years.

To piece together humankind's great migration, scientists blend DNA analysis with archaeological and fossil evidence to try to create a coherent whole—no easy task. A disproportionate number of artifacts and fossils are from Europe—where researchers have been finding sites for well over 100 years—but there are huge gaps elsewhere. "Outside the Near East there is almost nothing from Asia, maybe ten dots you could put on a map," says Texas A&M University anthropologist Ted Goebel.

As the gaps are filled, the story is likely to change, but in broad outline, today's scientists believe that from their beginnings in Africa, the modern humans went first to Asia between 80,000 and 60,000 years ago. By 45,000 years ago, or possibly earlier, they had settled Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Australia. The moderns entered Europe around 40,000 years ago, probably via two routes: from Turkey along the Danube corridor into eastern Europe, and along the Mediterranean coast. By 35,000 years ago, they were firmly established in most of the Old World. The Neanderthals, forced into mountain strongholds in Croatia, the Iberian Peninsula, the Crimea and elsewhere, would become extinct 25,000 years ago. Finally, around 15,000 years ago, humans crossed from Asia to North America and from there to South America.

Africa is relatively rich in the fossils of human ancestors who lived millions of years ago (see timeline, opposite). Lush, tropical lake country at the dawn of human evolution provided one congenial living habitat for such hominids as Australopithecus afarensis . Many such places are dry today, which makes for a congenial exploration habitat for paleontologists. Wind erosion exposes old bones that were covered in muck millions of years ago. Remains of early Homo sapiens , by contrast, are rare, not only in Africa, but also in Europe. One suspicion is that the early moderns on both continents did not—in contrast to Neanderthals—bury their dead, but either cremated them or left them to decompose in the open.

In 2003, a team of anthropologists reported the discovery of three unusual skulls—two adults and a child—at Herto, near the site of an ancient freshwater lake in northeast Ethiopia. The skulls were between 154,000 and 160,000 years old and had modern characteristics, but with some archaic features. "Even now I'm a little hesitant to call them anatomically modern," says team leader Tim White, from the University of California at Berkeley. "These are big, robust people, who haven't quite evolved into modern humans. Yet they are so close you wouldn't want to give them a different species name."

The Herto skulls fit with the DNA analysis suggesting that modern humans evolved some 200,000 years ago. But they also raised questions. There were no other skeletal remains at the site (although there was evidence of butchered hippopotamuses), and all three skulls, which were nearly complete except for jawbones, showed cut marks—signs of scraping with stone tools. It appeared that the skulls had been deliberately detached from their skeletons and defleshed. In fact, part of the child's skull was highly polished. "It is hard to argue that this is not some kind of mortuary ritual," White says.

Even more provocative were discoveries reported last year. In a cave at Pinnacle Point in South Africa, a team led by Arizona State University paleoanthropologist Curtis Marean found evidence that humans 164,000 years ago were eating shellfish, making complex tools and using red ocher pigment—all modern human behaviors. The shellfish remains—of mussels, periwinkles, barnacles and other mollusks—indicated that humans were exploiting the sea as a food source at least 40,000 years earlier than previously thought.

The first archaeological evidence of a human migration out of Africa was found in the caves of Qafzeh and Skhul, in present-day Israel. These sites, initially discovered in the 1930s, contained the remains of at least 11 modern humans. Most appeared to have been ritually buried. Artifacts at the site, however, were simple: hand axes and other Neanderthal-style tools.

At first, the skeletons were thought to be 50,000 years old—modern humans who had settled in the Levant on their way to Europe. But in 1989, new dating techniques showed them to be 90,000 to 100,000 years old, the oldest modern human remains ever found outside Africa. But this excursion appears to be a dead end: there is no evidence that these moderns survived for long, much less went on to colonize any other parts of the globe. They are therefore not considered to be a part of the migration that followed 10,000 or 20,000 years later.

Intriguingly, 70,000-year-old Neanderthal remains have been found in the same region. The moderns, it would appear, arrived first, only to move on, die off because of disease or natural catastrophe or—possibly—get wiped out. If they shared territory with Neanderthals, the more "robust" species may have outcompeted them here. "You may be anatomically modern and display modern behaviors," says paleoanthropologist Nicholas J. Conard of Germany's University of Tübingen, "but apparently it wasn't enough. At that point the two species are on pretty equal footing." It was also at this point in history, scientists concluded, that the Africans ceded Asia to the Neanderthals.

Then, about 80,000 years ago, says Blombos archaeologist Henshilwood, modern humans entered a "dynamic period" of innovation. The evidence comes from such South African cave sites as Blombos, Klasies River, Diepkloof and Sibudu. In addition to the ocher carving, the Blombos Cave yielded perforated ornamental shell beads—among the world's first known jewelry. Pieces of inscribed ostrich eggshell turned up at Diepkloof. Hafted points at Sibudu and elsewhere hint that the moderns of southern Africa used throwing spears and arrows. Fine-grained stone needed for careful workmanship had been transported from up to 18 miles away, which suggests they had some sort of trade. Bones at several South African sites showed that humans were killing eland, springbok and even seals. At Klasies River, traces of burned vegetation suggest that the ancient hunter-gatherers may have figured out that by clearing land, they could encourage quicker growth of edible roots and tubers. The sophisticated bone tool and stoneworking technologies at these sites were all from roughly the same time period—between 75,000 and 55,000 years ago.

Virtually all of these sites had piles of seashells. Together with the much older evidence from the cave at Pinnacle Point, the shells suggest that seafood may have served as a nutritional trigger at a crucial point in human history, providing the fatty acids that modern humans needed to fuel their outsize brains: "This is the evolutionary driving force," says University of Cape Town archaeologist John Parkington. "It is sucking people into being more cognitively aware, faster-wired, faster-brained, smarter." Stanford University paleoanthropologist Richard Klein has long argued that a genetic mutation at roughly this point in human history provoked a sudden increase in brainpower, perhaps linked to the onset of speech.

Did new technology, improved nutrition or some genetic mutation allow modern humans to explore the world? Possibly, but other scholars point to more mundane factors that may have contributed to the exodus from Africa. A recent DNA study suggests that massive droughts before the great migration split Africa's modern human population into small, isolated groups and may have even threatened their extinction. Only after the weather improved were the survivors able to reunite, multiply and, in the end, emigrate. Improvements in technology may have helped some of them set out for new territory. Or cold snaps may have lowered sea level and opened new land bridges.

Whatever the reason, the ancient Africans reached a watershed. They were ready to leave, and they did.

DNA evidence suggests the original exodus involved anywhere from 1,000 to 50,000 people. Scientists do not agree on the time of the departure—sometime more recently than 80,000 years ago—or the departure point, but most now appear to be leaning away from the Sinai, once the favored location, and toward a land bridge crossing what today is the Bab el Mandeb Strait separating Djibouti from the Arabian Peninsula at the southern end of the Red Sea. From there, the thinking goes, migrants could have followed a southern route eastward along the coast of the Indian Ocean. "It could have been almost accidental," Henshilwood says, a path of least resistance that did not require adaptations to different climates, topographies or diet. The migrants' path never veered far from the sea, departed from warm weather or failed to provide familiar food, such as shellfish and tropical fruit.

Tools found at Jwalapuram, a 74,000-year-old site in southern India, match those used in Africa from the same period. Anthropologist Michael Petraglia of the University of Cambridge, who led the dig, says that although no human fossils have been found to confirm the presence of modern humans at Jwalapuram, the tools suggest it is the earliest known settlement of modern humans outside of Africa except for the dead enders at Israel's Qafzeh and Skhul sites.

And that's about all the physical evidence there is for tracking the migrants' early progress across Asia. To the south, the fossil and archaeological record is clearer and shows that modern humans reached Australia and Papua New Guinea—then part of the same landmass—at least 45,000 years ago, and maybe much earlier.

But curiously, the early down under colonists apparently did not make sophisticated tools, relying instead on simple Neanderthal-style flaked stones and scrapers. They had few ornaments and little long-distance trade, and left scant evidence that they hunted large marsupial mammals in their new homeland. Of course, they may have used sophisticated wood or bamboo tools that have decayed. But University of Utah anthropologist James F. O'Connell offers another explanation: the early settlers did not bother with sophisticated technologies because they did not need them. That these people were "modern" and innovative is clear: getting to New Guinea-Australia from the mainland required at least one sea voyage of more than 45 miles, an astounding achievement. But once in place, the colonists faced few pressures to innovate or adapt new technologies. In particular, O'Connell notes, there were few people, no shortage of food and no need to compete with an indigenous population like Europe's Neanderthals.

Modern humans eventually made their first forays into Europe only about 40,000 years ago, presumably delayed by relatively cold and inhospitable weather and a less than welcoming Neanderthal population. The conquest of the continent—if that is what it was—is thought to have lasted about 15,000 years, as the last pockets of Neanderthals dwindled to extinction. The European penetration is widely regarded as the decisive event of the great migration, eliminating as it did our last rivals and enabling the moderns to survive there uncontested.

Did modern humans wipe out the competition, absorb them through interbreeding, outthink them or simply stand by while climate, dwindling resources, an epidemic or some other natural phenomenon did the job? Perhaps all of the above. Archaeologists have found little direct evidence of confrontation between the two peoples. Skeletal evidence of possible interbreeding is sparse, contentious and inconclusive. And while interbreeding may well have taken place, recent DNA studies have failed to show any consistent genetic relationship between modern humans and Neanderthals.

"You are always looking for a neat answer, but my feeling is that you should use your imagination," says Harvard University archaeologist Ofer Bar-Yosef. "There may have been positive interaction with the diffusion of technology from one group to the other. Or the modern humans could have killed off the Neanderthals. Or the Neanderthals could have just died out. Instead of subscribing to one hypothesis or two, I see a composite."

Modern humans' next conquest was the New World, which they reached by the Bering Land Bridge—or possibly by boat—at least 15,000 years ago. Some of the oldest unambiguous evidence of humans in the New World is human DNA extracted from coprolites—fossilized feces—found in Oregon and recently carbon dated to 14,300 years ago.

For many years paleontologists still had one gap in their story of how humans conquered the world. They had no human fossils from sub-Saharan Africa from between 15,000 and 70,000 years ago. Because the epoch of the great migration was a blank slate, they could not say for sure that the modern humans who invaded Europe were functionally identical to those who stayed behind in Africa. But one day in 1999, anthropologist Alan Morris of South Africa's University of Cape Town showed Frederick Grine, a visiting colleague from Stony Brook University, an unusual-looking skull on his bookcase. Morris told Grine that the skull had been discovered in the 1950s at Hofmeyr, in South Africa. No other bones had been found near it, and its original resting place had been befouled by river sediment. Any archaeological evidence from the site had been destroyed—the skull was a seemingly useless artifact.

But Grine noticed that the braincase was filled with a carbonate sand matrix. Using a technique unavailable in the 1950s, Grine, Morris and an Oxford University-led team of analysts measured radioactive particles in the matrix. The skull, they learned, was 36,000 years old. Comparing it with skulls from Neanderthals, early modern Europeans and contemporary humans, they discovered it had nothing in common with Neanderthal skulls and only peripheral similarities with any of today's populations. But it matched the early Europeans elegantly. The evidence was clear. Thirty-six thousand years ago, says Morris, before the world's human population differentiated into the mishmash of races and ethnicities that exist today, "We were all Africans."

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware this website contains images, voices and names of people who have died.

Learning module:

Deep time history of australia.

Investigation 2: Two big ideas in deep time history in Australia

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Big Idea 1: Scientists believe that the first Australians came from somewhere else

2.3 Big Idea 2: We can learn about Aboriginal culture in ancient Australia from archaeology

2.4 What have we learned about ancient or deep time Australia?

The arrival of the first australians.

National Museum of Australia

Islands in the Torres Strait

Where did the first Australians come from?

The Australian people arrive in Australia.

How did people know there was land?

Using DNA and archaeological evidence.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people believe that people have always been in Australia. They are part of the Dreaming, the time of creation of all the world.

Scientists and archaeologists believe that the first people arrived in Australia from somewhere else, between 50,000 years ago and 65,000 years ago. Estimates of when people first arrived in Australia is constantly changing as new evidence is discovered and as scientific techniques of measuring the past are improved.

Scientists do not know how or where modern humans developed, but there are currently two main scientific ideas that are under investigation.

The first scientific idea is that modern humans or homo sapiens developed quite suddenly in Africa and then spread, eventually displacing all earlier types of homo erectus (pre-modern humans) such as Neanderthals, which had been around for about 2 million years.

This might have looked a little like this:

Eliane Touma

Map showing possible routes taken by homo sapiens out of Africa

The second scientific idea is that modern humans appeared in many parts of the world at about the same time , mixing with earlier types of homo erectus .

Whichever way this happened, according to science, the earliest humans made their way through Asia and eventually moved southwards towards the Australian continent.

The first people arrive in Australia

Australia looked very different 65,000 years ago. The continent was larger than it is today. Some land that existed in ancient times is now under the sea. Australia was also joined to other land masses that are now separate islands.

Map A: Australia and South East Asia today

Map B: Land in Australia and South East Asia today and 65,000 years ago

Map C: Most likely ancient migration routes to Australia

Adapted from Stuart Hawkins et al., ‘Oldest human occupation of Wallacea at Laili Cave, Timor-Leste, shows broad-spectrum foraging responses to late Pleistocene environments’, Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 171, 2017, p. 59

1. Map A shows what Australia looks like now. Map B shows what it looked like about 65,000 years ago. There was much more land as the sea was much lower than it is today. Which two large islands, one in the north and one in the south, were joined to Australia then?

2. Map C shows how people might have migrated to Australia at this time. This map shows some different possible landing points. Why do you think scientists are not sure which landing points Aboriginal people used? [Hint: think about the evidence that would be needed to confirm this and the difficulty of finding this evidence many thousands of years later.]

The first people probably came to Australia from around the area that is now Timor. To get to Australia, they must have made a canoe voyage of about 90 to 150 kilometres of open water, which would have been a remarkable maritime achievement. But how did they know that Australia was there?

Imagine that you are about to go on a trip to another place. You cannot see the land — but you know it exists. How might you know that land exists?

3. Write down how each of the hints below might have told people that there was land even though they could not see it. If you need more help, hover over the relevant clue at the bottom.

a) Birds would help you know that there was land because…

b) Clouds would help you know that there was land because…

c) Smoke would help you know that there was land because…

d) Floating vegetation would help you know that there was land because…

Where are birds’ nests found?

Where do clouds form?

What might cause smoke?

Where might the vegetation have come from?

Another possibility is that people could see the land, and that was how they knew it was there. Then perhaps they could ‘island hop’ towards Australia.

A recent scientific study might explain what happened. We know that there is ancient land that is now under water off the Australian coast. These would have only been partly under water when people first came to Australia. They would have been islands then. Scientists have worked out how far away each of these hundreds of islands would have been from each other, and whether a person standing on the highest point of each island could have seen another island in the distance. If they could see another island, they could travel there and see the next island. In this way they could in theory have ‘island-hopped’ from Asia to Australia, paddling or sailing canoes from Timor to Australia, perhaps using the summer north-west winds that blow strongly from Timor towards Australia.

4. We will never find any physical evidence (such as spears, clubs, paintings or bones) from the first people who arrived on the Australian landmass. Why not?

Using DNA and archaeological evidence

Another theory is based on a study of the DNA of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia.

DNA is deoxyribonucleic acid. It is the hereditary material in humans and other life forms. It makes us what we are. We inherit it from our parents. People of different regions have some differences in their DNA, so analysing a person’s DNA can help you trace back their family history over many thousands of years.

Modern DNA studies suggest that Australian Aboriginal people, Papua New Guinean highlanders and the Mamanawa people of the Philippines were all descended from the same group who left Africa, and settled in different places after a journey of several thousand years.

People who have the same ancestors have very similar DNA. By studying DNA samples taken from Aboriginal people living in Australia today, scientists have been able to see when and where people settled across ancient Australia.

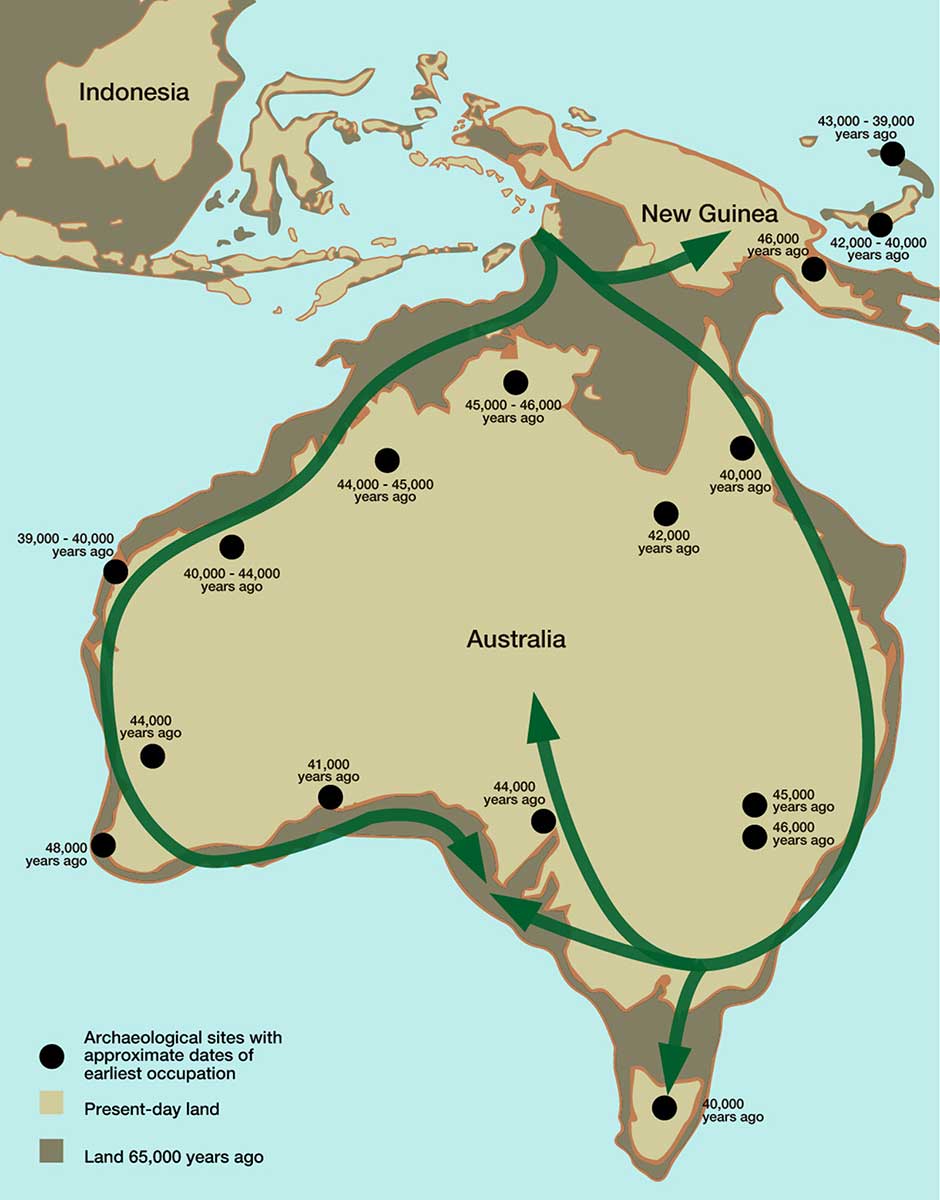

Look at this map. The dots show different archaeological sites around Australia and the age of what was found there. The archaeological and DNA evidence show similar timeframes for the movement of people across ancient Australia.

Adapted from Ray Tobler et al., ‘Aboriginal mitogenomes reveal 50,000 years of regionalism in Australia’, Nature, vol. 544, no. 7649, 2017, p. 183

Map showing archaeological data and the likely migration routes of people around Australia

Use the map to answer these questions.

5. It is likely that people came to Australia from one of the landmasses to the west. Which modern country does the map suggest that was?

6. According to this evidence, people probably came down which side of Australia? How does the evidence show this?

7. When had people moved to all parts of Australia and Tasmania? (Hint: what is the most recent date you can find on the map?)

Why did people come to Australia? Was it an accidental voyage, such as a group of people out fishing being caught in a storm and washed off course? Or was it deliberate, a group of people setting off to settle in the new place — perhaps to escape conflict, or population pressures, or just out of a spirit of adventure?

We can probably never know. But whether it was accidental or deliberate, one voyage or many, imagine what the people would have felt as they waded ashore onto this new land.

8. List some emotions that you think they might have felt.

A term referring to the distant past.

In your report make sure you explain:

- where Australians came from

- how they knew that there was land to go to

- where they landed first

- when this movement happened

- what the evidence is that tells us this, and what evidence is not available

- what this can tell us about ancient or Deep Time Australia.

How to get to Australia … more than 50,000 years ago

Deputy Director, ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, James Cook University

Director, Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, University of Adelaide

ARC Laureate Fellow, JCU Distinguished Professor and Landscapes Theme Leader for the ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, James Cook University

Kimberley Foundation Ian Potter Chair in Rock Art and Professor of Australian Archaeology, Centre for Rock Art Research and Management, The University of Western Australia

Research Fellow, College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University

Senior Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO

Disclosure statement

Sean Ulm receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Alan Cooper receives funding from the Australian Research Council

Michael Bird receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Peter Veth receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Kimberley Foundation Australia.

Robin Beaman receives funding from Geoscience Australia and the Qld Dept of Environment and Science.

Scott Condie receives funding from a wide range of government organisations, foundations and industry.

University of Western Australia and CSIRO provide funding as founding partners of The Conversation AU.

James Cook University and University of Adelaide provide funding as members of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Over just the past few years, new archaeological findings have revealed the lives of early Aboriginal Australians in the Northern Territory’s Kakadu potentially as early as 65,000 years ago , from the Kimberley and Pilbara regions of Western Australia by about 50,000 years ago , and the Flinders Ranges of South Australia by around 49,000 years ago .

But how was it even possible for people to get to Australia in the first place? And how many people must have made it to Australia to explain the diversity of Aboriginal people today?

In a study published in Quaternary Science Reviews this week, we use new environmental reconstructions, voyage simulations, and genetic population estimates to show for the first time that colonisation of Australia by 50,000 years ago was achieved by a globally significant phase of purposeful and coordinated marine voyaging.

Past environments

Australia has never been connected by dry land to Southeast Asia. But at the time that people first arrived in Australia, sea levels were much lower , joining the Australian mainland to both Tasmania and New Guinea.

Read more: Australia's coastal living is at risk from sea level rise, but it's happened before

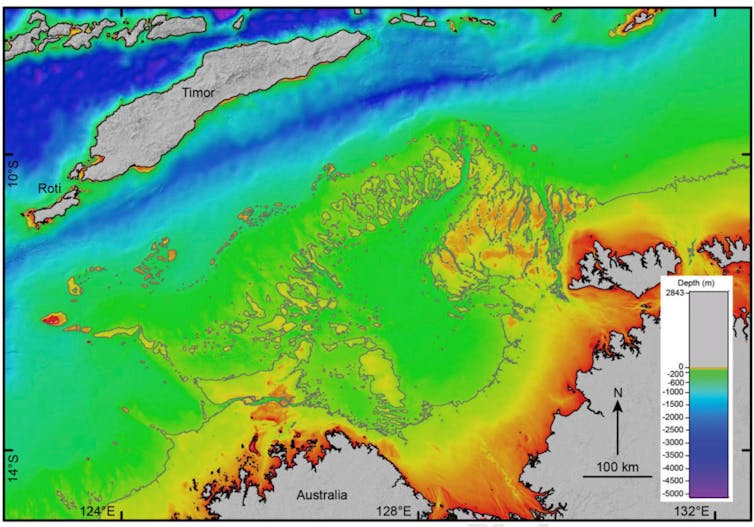

Our analysis using new high-resolution mapping of the seafloor shows that when sea levels were 75m or lower than present, a string of more than 100 habitable, resource-rich islands were present off the coast of northwest Australia.

These islands were directly visible from high points on the islands of Timor and Roti and as close as 87km.

This chain of now mostly submerged islands - the Sahul Banks - was almost 700km long. They represented a very large target for either accidental or purposeful arrival.

How difficult was it to get to Australia?

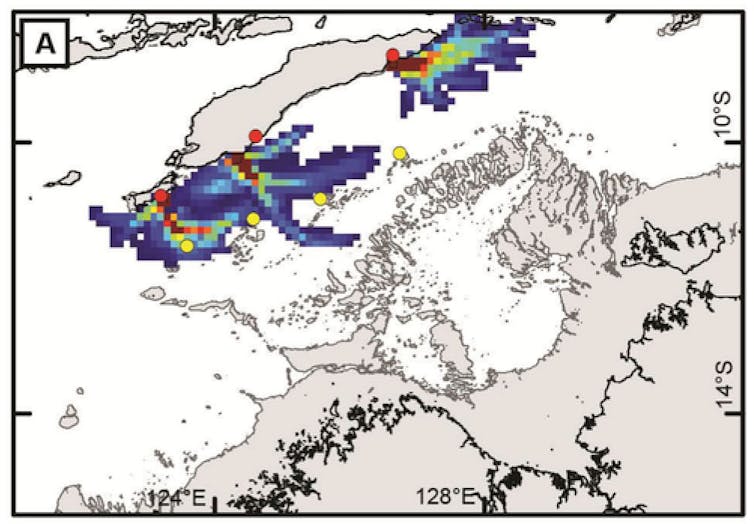

Combining modelled winds and ocean currents with particle trajectory modelling, we simulated voyages from three sites on the islands of Timor and Roti. This is similar to the approach used to model the movements of wreckage from the missing Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 .

In our model, we simulated the “launch” of 100 vessels from each site on February 1 each year for 15 years. The date was chosen to correspond to the main summer monsoon period when winds are generally blowing to the east-southeast, thereby maximising the chance of successful crossings.

The results clearly indicate that accidental arrival by drifting alone is very unlikely at any time. But the addition of even modest paddling towards the Sahul Banks islands results in a high proportion of successful arrivals over four to seven days. The highest probability of a successful landfall is associated with launching points on western Timor and Roti.

How many people did it take to colonise Australia?

Researchers have long speculated about how many people originally colonised Australia. Some have argued that Australia must have been colonised by accident, perhaps by just a few people.

Others have suggested a steady trickle of colonists. Estimates of the founding population have ranged from 1,000 to 3,000 .

The genetic evidence shows that Australia was colonised in a single phase, perhaps at multiple locations, but with very limited gene flow after initial colonisation.

Read more: DNA reveals Aboriginal people had a long and settled connection to country

The diversity of mitochondrial DNA lineages found in Aboriginal populations allows us to estimate the minimum size of the original colonising population. Mitochondrial DNA is only inherited from mothers.

Aboriginal mitochondrial DNA diversity alone represents at least nine to ten separate lineages.

Assuming that every mitochondrial lineage was represented in the founding population by four to five females (such as a family group containing a mother and her sister, and two daughters) the currently known nine to ten lineages would equate to around 36-50 females.

This is a conservative estimate, as founding populations of fewer than ten females per lineage have a low chance of long-term survival due to variations in reproductive success.

If an overall, again conservative, female to male ratio of 1:1 is assumed for the colonising party, the inferred founding population would be around 72-100 people. It was likely much larger (perhaps 200-300) because of the strong potential for related family groups to share similar mitochondrial lineages, which would be underestimated as a single founding lineage.

Clearly, a population of even the minimum estimated size is unlikely to have arrived accidentally on Sahul.

What does it all mean?

A lot of earlier thinking about how people arrived in Australia was based on the assumption that the first modern humans to sweep out of Africa and colonise the distant lands of Australia and New Guinea were somehow more limited in their cognitive and technological capacities than later humans (that is, all of “us”).