- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Halfway Anywhere

The Tour Divide: What, Where, Why, and How?

By Mac Leave a Comment

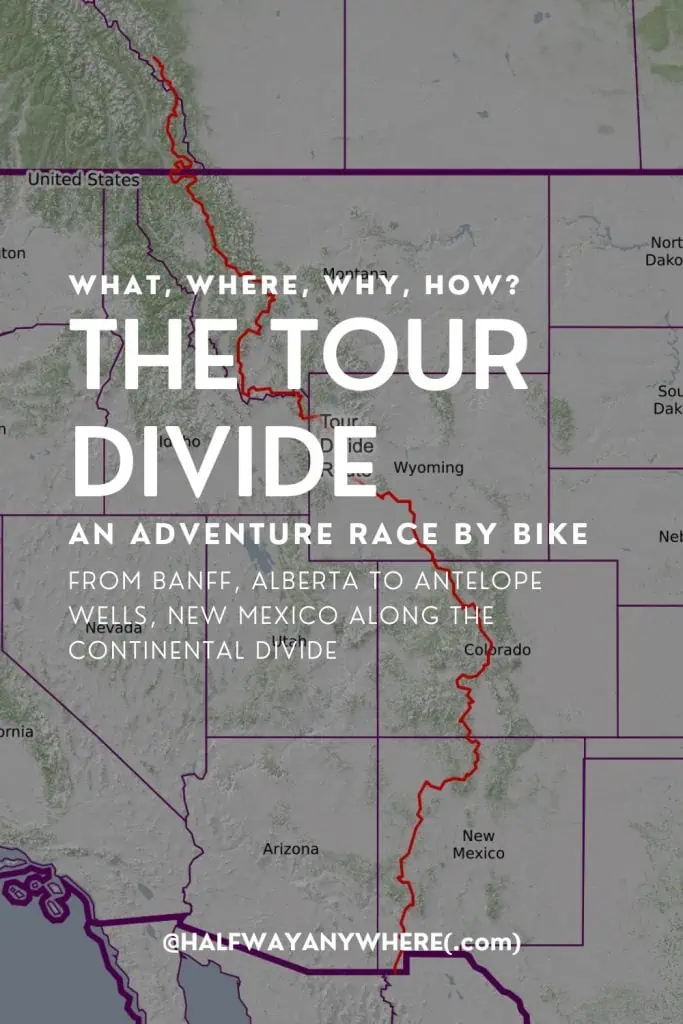

The Tour Divide is an annual 2,700-mile (4,300 km) self-supported bikepacking race following the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR). Most of the route follows dirt and gravel roads with a few sections of pavement or singletrack sprinkled in for good measure (along with the occasional hike-a-bike section).

Cursory internet sleuthing tells me that the current iteration of the Tour Divide began in 2008. However, the first individual time trial of the route was in 2005, and people have been riding the GDMBR since as early as 1997 when the Adventure Cycling Association first mapped it.

Speaking of websites, the current Tour Divide website hasn’t been updated since 2014 and leaves much to be desired. Or perhaps the state of the website is instead part of the Tour Divide’s charm? Mystique? Neato-ness?

You may already have more questions than answers if you’ve encountered this with zero knowledge of the Tour Divide or the GDMBR. Fear not; they will be addressed. Also, know that I will likely have many of the same questions. I intend to answer said questions by participating in (and hopefully completing) this year’s Tour Divide.

That said, I’ve been doing my research (and investing heavily in bikepacking gear).

What Is the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route?

The northern terminus of the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR) is in Jasper (it was in Banff – the start of the Tour Divide – until 2018), a resort town in Alberta, Canada. It then heads south for over 3,000 mi / 4,800 km to its southern terminus at the US-Mexico Border at Antelope Wells, New Mexico. It can be ridden in either direction, but it’s traditionally ridden southbound.

Along with the Arizona Trail and the Colorado Trail, it comprises the most significant leg of bikepacking’s Triple Crown; similar to the thru-hiking Triple Crown comprised of the Pacific Crest Trail , Continental Divide Trail , and Appalachian Trail .

The route is almost entirely along dirt and gravel roads and is, for the most part, not a technical ride (i.e., you don’t need to be an expert-level mountain biker to navigate the GDMBR). Yes, there are a few short sections of singletrack, but overall, this route is suited for gravel or mountain bikes (but certainly not road bikes).

The GDMBR is approximately 3,000 mi / 4,800 km long and has over 133,000 ft / 40,500 m of climbing and an equal amount of descent. It passes through seven states/provinces: Alberta, British Columbia, Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico. Despite beginning in Canada (as in riders must pass immigration at a border crossing), the route does not enter Mexico; it ends (or begins) at the US-Mexico Border.

The Difference Between the Tour Divide and the GDMBR

You may be asking yourself, as I have, what’s the difference between the Tour Divide and the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route? The answer? Nothing. Kind of.

The Tour Divide is the name of the annual self-supported race of the GDMBR . Put another way, the Tour Divide follows the GDMBR. However, it begins in Banff instead of Jasper; Banff was the northern terminus of the GDMBR until 2018, when it was moved to Jasper. At least, that’s all you need to know if you’re not racing and/or riding the Tour Divide. What’s self-supported? It means that racers are only afforded resources available to everyone else participating.

For example, staying at a hotel? Perfectly fine. Staying at a friend’s house? Not okay.

When you drill down to the details, there are a few sections where the Tour Divide diverges from the GDMBR. But for all intents and purposes, they’re the same; again, unless you’re concerned about racing the Tour Dviide, then there are a few spots you need to take note of.

Every year, people bikepack all or part of the GDMBR on their own (in both directions). These people can take as much or as little time as they like – many presumably even enjoy their experience. Meanwhile, others decide to race the Tour Divide beginning on the second Friday of June at the northern terminus in Banff, Alberta (in Canada). The latter group’s enjoyment often falls more heavily into the Type II (or even Type III) fun category.

The GDMBR Versus the Continental Divide Trail

When I first hiked the Continental Divide Trail (CDT), I met one person in Island Park, Idaho, who was riding the Divide; I had no idea what they were doing, what the Tour Divide was, or what the GDMBR was. The cyclist was stoked to see me and my CDT hiking buddy, but we thought ourselves cooler than him because what could be cooler than hiking the CDT?

How things have changed. I apologize for not greeting you with the enthusiasm you deserved, anonymous 2017 Tour Divide racer.

Despite the CDT following a lot of dirt and gravel roads – that would be suitable for bikepacking – there’s actually very little overlap between the two routes. Yes, there will be opportunities for northbound CDT thru-hikers to see Tour Divide riders, but many will pass like ships in the night.

The Tour Divide starts too early for southbound CDT hikers to catch any riders, but they could still encounter northbound GDMBR riders during their thru-hikes. Remember, play nice if/when you see each other out there. We’re all out there doing awesome things in nature. There’s no need to perpetuate a bikepacker-backpacker divide (on the Divide).

How to Participate in the Tour Divide

The community that has made the Tour Divide what it is today doesn’t exist as an official organization or entity. Instead, it’s willed into being by the yearly riding crop’s cohesion, carrying on traditions from and iterating upon actions of previous years’ cyclists.

There’s no sign-up form, no entry fee, no website (at least not a website updated in the last decade), and no organized event at the starting line in Banff (or at the finish line at Antelope Wells, New Mexico).

Most of the organization appears to come from Facebook groups (typically some of the most toxic online cesspools, but in rare cases, useful information corners). Every year, participants who provide tracking information (using a device such as a Garmin inReach Mini 2 ) to trackleaders can be watched online as they move down the course.

You show up in Banff, start riding south on the second Friday in June, tell anyone who asks that you’re riding the Tour Divide, and BOOM! you’re officially racing the Tour Divide. I’ve heard that in recent years that the community attempts to organize waves of riders (based on estimated finishing time) to ease impacts and congestion on/along the start of the race. Don’t want the local government to come in and try to shut down the unofficial race, after all.

Maybe one day, the magic of this unofficial, unorganized, organized, official bikepacking race will wane as permits, regulations, and rules are imposed with increasing popularity and awareness of the event. Maybe someone will write a best-selling book about the Tour Divide and blow it up like a certain unnamed book did to a certain unnamed trail in the Western United States.

Apparently, you’re supposed to send in a letter of intent to a random email address that I suspect is maintained by the crew at Bikepacking.com , but the letters of intent used to be posted to the Tour Divide website (which seems like it was a fun tradition that’s now sadly gone as of 2010).

For now, you only need to get on your bike and ride.

The Tour Divide is the unofficial orrifical self-supported race of the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route, with a few changes to the route. Simple enough, right?

It’s an incredible test of physical and mental endurance, with many riders forgoing sleep to put in more hours on the bike (how many hours I sleep every night is something I’m interested in seeing).

According to DotWatcher , since the Tour Divide’s conception in 2008, only 716 riders have completed the race (this number is likely not 100% accurate, but it’s about as good as we can do). Hopefully, after this year’s race, I will be able to count myself among the fewer than 1,000 total finishers.

For now, it’s time to go and ride my bike .

You'll Like These Too:

Share this post:.

Tour Divide

- the Route (description)

- The Challenge

- Grand Départ

- Rider Resources

- News & Notes (blog)

- News & Notes

- `11 Race Updates

- `11 Rider Call-Ins

- `11 ITTD Updates

- `10 Race Updates

- `10 ITTD Updates

- `09 Race Updates

- `09 ITTD Updates

- `08 Race Updates

- About Start List

- `11 TD Start List

- `11 ITT-D Start List

- `11 Letters of Intent

- `10 TD Start List

- `10 Letters of Intent

- Start List & LOI Archive

The Grand Tour of MTB

Banff, ab ca - antelope wells, nm usa, expedition bike racing at it's finest, great divide mountain bike route, one stage: 2745mi / 4418km self-supported racing, great continental divide mountain bike race, 13th of june, 2014.

Decidedly not for sprinters, this battle royale braves mountain passes and windswept valleys of the Continental Divide from hinterlands of the Canadian Rockies to badlands of the Mexican Plateau.

‘Tour Divide’ Champ’s Secrets To Conquer A Mountain Range

Share this:.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

[leadin] Unassuming cyclist Josh Kato crushed last year’s Great Tour Divide, a self-supported race that crosses the United States north to south over the Rocky Mountains.[/leadin]

Imagine your longest day in the saddle. Let’s go with 100 miles….that’s a typical long distance endurance ride. Now double it. Then, repeat…for 14 days, 11 hours, and 37 minutes straight. And for good measure, do it over the most rugged mountain range in America and entirely off-pavement.

That’s precisely what the 40-year-old Washington nurse and endurance cyclist did at last year’s Great Tour Divide (GTD). His time not only won the 2,745-mile event, but it set the course record.

We caught up with Kato to discuss the highs and lows of endurance cycling, and his secret training weapons, including patience, a fat bike, and donuts!

GearJunkie: Two years ago, your GTD didn’t go as planned. Can you tell us more about that?

Josh Kato: 2014 was supposed to be the year I was going to accomplish a dream of competing in the Tour Divide. I was riding much stronger than I had anticipated and on day three of the race, in Montana (around mile 300), I ended up crashing in the mud and snow. It was a bit of a worst-case scenario type of wreck. I landed wrong, fractured my fibula, tore my hamstring, and gashed the back of my leg which subsequently got infected. I rode until around mile 1,100 before I called it quits.

That hurt. Dropping out of something I had poured so much time, money, and energy into. It was as if I had let myself down. I was rather depressed. I figured I wouldn’t ever be able to get time off of work again to give it another go.

So that’s 800 miles with a broken leg! How did you push through that sort of pain? Did you underestimate the injury?

Ha! I said I was a nurse. Never said I was a good one.

Yeah, after my wreck, I realized fairly quickly that something was very wrong with my leg, but denial is a powerful tool. I truly never thought I’d be able to get the time off from work to do the race again so I was committed to pushing on as long as I could turn the pedals. When it got to the point that it was no longer physically possible, I called it on the race.

I’m 40 and my body has been around the block a few times. It’s pretty commonplace to have aches and pains that don’t go away very quickly. In my head, I was pretty sure what I’d done, but also realized I probably wouldn’t incur any permanent disability from it. Of course, had I completely torn my hamstring rather than just a partial tear that would have taken a huge amount of recovery time. It got to the point that I had to lift my leg to the pedal by pulling with my hand a length of strap wrapped around my foot, like a lasso.

On the GTD, everyone hurts. Some things can be overcome and some things can’t. Perhaps being in healthcare, it’s easy to minimize suffering. Acute pain isn’t a permanent ailment. It’s just something that needs to be worked through.

So last year–you decided to give it another go! You must have felt you had unfinished business.

When I found out I was going to get the vacation time from work, I trained like a madman. I wanted to finish what I had started and made every effort to make sure I could.

I never trained with the goal of winning. I trained to finish. I’m not a very competitive guy. Except with myself. I guess I was able to achieve a level of conditioning that allowed me to compete with the amazing field of competitors we had last year.

“I think one of the most important things I did was train with a heavier bike than I used in the Divide.”

What kind of mileage are you churning through to train for the GTD?

In my lead up to the Divide in 2015, I rode about 3,000 miles with an unusual amount of climbing — round 450,000 feet. We have a lot of hills in Washington. Almost all of my riding was on very poor gravel roads, trails, and abandoned logging roads. Very Divide-like terrain.

I think one of the most important things I did was train with a heavier bike than I used in the divide. I purposely go out and try to find the most challenging rides I can do. For a race like the Divide, a rider has to get used to going slow uphill with a heavy bike. It’s a mental thing.

Of course, we had a very mild winter last year in Washington so I was able to churn out some good rides early in the season. This year is making me get a bit more creative with training. Fat bikes are a great invention for training. This amount of training and having a job means I have to sacrifice a fair bit of other items in life. When I’m not at work, I’m riding, running, or prepping in some way for the Divide. It’s a huge time commitment.

You work as a nurse – does shift work lend itself to training and pulling in long days in the saddle?

I work the night shift. So yes, I guess it helps to know what keeps your mind going at 3am .

I think one thing that nursing lends itself to more than anything is seeing the struggles of other people. The body can overcome some pretty astonishing things. Some people have an amazing amount of will to keep going when the odds are stacked against them. It’s a good reminder to hear people tell me that they just wished they could be well enough to be outside roaming through the hills. People remind me every day to not take health for granted.

Obviously, you love to ride – do you cross-train to keep it fresh?

The best rides are the ones that are not about the ride at all. I only wish that fly-fishing was a better workout. That’s my main passion. Nothing like standing in a river with a bit of graphite. Sadly, it doesn’t work the cardio system too well.

You rode in the Smoke’n Fire 400 last year. Do you use these ‘middle distance’ bikepacking rides as training rides? How many do you take on each year?

The Smoke’n Fire is a super fun event! Excellent scenery and awesome trail sections. My first bikepacking race was the 2014 Tour Divide. My second was the 2015 Divide. My third was the Smoke’n Fire 400. I finished the Divide in June. The SNF 400 was in September. I barely rode after the Divide. I had to go fishing! I used the SNF 400 as a test for myself to see how I’d do “off the couch”. I was very happy with my result.

It was also interesting doing the full sleep deprivation thing. In the Tour Divide, I slept every night. It’s a long race. These shorter races seem to be much more about sleep deprivation. On some of the last climbs in the SNF 400 I was hallucinating pretty well. I remember seeing Jay Petervary (who wasn’t in the race) sitting alongside the road petting a capybara. Also, when I rode into Boise at the end of that race I heard someone shout my name. I thought that might be a hallucination as well.

You weren’t hallucinating. I was following the leader board and cheering finishers at the end of the race–I gave a shout out to you.

Funny! Good to know now I wasn’t that bad off. I guess I’m not cut out for the full sleep deprivation thing. I’d enjoy doing more races but the work schedule interferes quite a bit.

“You gotta find a way to keep going. Donuts help a lot.”

Pulling in mile after mile … I’m sure it can be incredibly emotional, but on both sides. You must hit both extreme highs and lows. How do you monitor your emotional state?

The Tour Divide is so long that yes, you go through every single emotion possible, as well as some that you didn’t realize were in you. Riding mostly alone, pushing yourself to unfamiliar physical limits, that’s the easy part. The emotional aspect is the hard part. You gotta find a way to keep going. Donuts help a lot. In reality, I always try to remind myself that no matter how bad I feel, how down in the dumps my mind is, that things will get better at some point. All bleeding stops, eventually. Ultra-racing is very much like that.

So you’re 40. That’s venturing into middle age. But you’re at the top of the game. Jay P. is even older. Does endurance riding get better with age?

JK: Yup, 40. I’ll hit 41 before this years Divide. Guys like Jay P. and Jefe Branham are very inspirational to me. They keep going and going. I’d like to say I’ve solved the mystery of the 40ish racer and ultra-endurance but I haven’t got “the” answer. One of the only things that I can determine is that we keep realizing our gig might be up at any time. So we gotta get done with a few things as fast as we can. I know that I can ride much longer than I could when I was younger. Perhaps it’s an impatience thing with youth. Perhaps we’ve just learned through life experience to endure more. Or maybe we are just more determined to show up the youngsters. I do know I focus on the journey far more than the speed. Oh, I wanna go fast, but the journey means a lot more to me now than it did when I was younger.

You’re quite a photographer. (All photos in this post are taken by Josh Kato). How do you balance pushing so hard, so long, yet taking time to smell the proverbial roses?

The main difference between my touring speed and racing speed are the number of photos I take during a ride. Landscape photography is a hobby of mine and I do love getting a shot of a fleeting moment in a beautiful place. My wife can attest that my camera is rarely out of hand during a tour. Nonetheless, even when racing the best of the best ultra-guys I’m not going to pass up a landscape that creates an emotional response in me.

What kind of camera do you take with you on the bike?

During races, I carry a small point and shoot that takes decent images. During the Divide, I carried a Canon S110. It does great while shooting on the go. While touring I use either a Sony RX100 or Fuji XE-1.

Any advice on how to keep the camera readily available while riding?

I almost always ride with a hydration pack. The packs with a small pocket on the shoulder strap are very nice to be able to tuck a small camera into. I then use a carabiner to clip the lanyard to my sternum strap so I can drop the camera should I need to brake quickly. Of course this only works well if it’s dry outside. I have yet to try a waterproof camera that has the image quality I want. When it rains, Ziploc bags are my friend.

So what’s your ride schedule look like this year?

I don’t have a huge agenda other than having another go at the Tour Divide. The race just kind of sticks in your head. Amazingly, I got the time off of work to go again, so I’m not going to pass it up. Not sure I’ll be able to train as much as last year but I’m certain I’m still going to have a blast. Other than the Divide, we’ll just have to see. I do know I need to get some more fly fishing trips in this year.

Thanks Josh and good luck this year!

This year’s GTD will roll out of Banff, Alberta on June 10th. The website hosts some good background information, but for the latest check out the Tour Divide on Facebook . To follow Josh and all the cyclists in real time, head on over to the Tour Divide’s leaderboard at Trackleaders.com .

Steve Graepel is a Contributing Editor and Gear Tester at GearJunkie. He has been writing about trail running, camping, skiing, and general dirtbagging for 10+ years. When not testing gear with GearJunkie, he is a Senior Medical Illustrator on the Neurosurgery Team at Mayo Clinic. Based in Boise, Idaho, Graepel is an avid trail runner, camper, angler, cyclist, skier, and loves to introduce his children to the Idaho outdoors.

Follow Us On

Subscribe Now

Get adventure news and gear reviews in your inbox!

Join Our GearJunkie Newsletter

Gear Top Stories Deals

- Performance

- Strava Updates

- English (US)

- Español de América

- Português do Brasil

Get Started

Ulrich "Uba" Bartholmoes: 2023 Tour Divide Winner

Mountain Biking

, by Greg Heil

Bikepack racing is, without a doubt, the most grueling ultra-endurance cycling discipline in the world. There are no support vehicles, no teammates, no course markings, and no help if (when) racers get injured.

And the clock never stops.

The masochistic racers who consider bikepacking a good idea subject themselves to a constant onslaught of harsh elements on little sleep as they tirelessly pedal thousands of miles in the hopes of both beating their competitors—and maybe setting a course record along the way.

The Tour Divide is "the mother of all bikepacking races," according to Ulrich Bartholmoes , aka "Uba," winner of the 2023 Tour Divide. "It's the oldest one, it's one of the most prestigious [bikepacking] races."

In many ways, the inspirational Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR) (known as the "Tour Divide" when raced every year beginning in June) spawned the groundswell of bikepacking that has turned an obscure niche activity into an international phenomenon. Covering about 2,745 miles / 4,417 km, the route runs from Banff, Alberta, to Antelope Wells, New Mexico (on the US/Mexico border). Riders will climb over 200,000 grueling vertical feet (60,960m) along the way from Canada to Mexico. Roughly tracing the spine of the continent, the GDMBR traverses some of the most stunning landscapes on Planet Earth. The sub-ranges of the Rocky Mountains change dramatically as riders pedal from north to south. Other landscapes are mixed in, too, such as the wide-open wasteland of Wyoming's Great Basin and the arid desert of New Mexico.

There is no governing body overseeing races like the Tour Divide. There's no entry fee (or reward at the end) or registration required—and the competitors like it that way. However, each bikepacking race does have its own loose set of rules—usually published online. In the Tour Divide, SPOT GPS trackers are used to track racers' positions and record their time on the course. Most importantly, the Tour Divide is entirely self-supported. Racers can use whatever publicly-available services can be found along the course, such as bike shops, hotels, and restaurants. But they can't receive any private help from friends or family—doing so would be grounds for disqualification. Forget having a team car with spare bikes on the roof. When you race the Tour Divide, you're 100% on your own.

Uba and the 2023 Tour Divide

Uba is originally from Munich, Germany, but now calls Girona, Spain, home. Having turned 37 years old while on the course, Uba won the 2023 Tour Divide with a time of 14 days, 3 hours, and 23 minutes. That effort earned him the second-fastest course time ever recorded, about 4.5 hours shy of the venerable Mike Hall's 2016 course record of 13 days, 22 hours, and 51 minutes.

RELATED: How to plan your first bikepacking adventure

I hopped on a call with Uba to hear about his incredible effort on the Tour Divide. We spoke about the biggest challenges along the route, the most rewarding moments, whether or not his time can be compared to Mike Hall's, how he uses Strava to plan and navigate long-distance races, and much more. Read on for the full scoop:

Greg Heil, Strava: I read that since 2019 you've attempted 19 events and won 14 of them, including an impressive third-place finish in Unbound Gravel just a few weeks before the Tour Divide while dealing with some serious mechanicals. But before 2019, can you tell us a little bit about what you were up to and where you were at? Can you set the stage for people who are unfamiliar with your career up to this point?

Ulrich Bartholmoes — "Uba": I was riding a downhill bike in my youth when I was going to school. Then I had a little break for studies and [went] a bit more to the flatlands and [worked] a bit more. I always [say that] back then, I was only riding the office chair, so it was a bit different. I got on my first bike back in 2013. So something like 10 years ago.

I started cycling and competing a bit in these gran fondo-like races, which are well-known and a big thing in Europe, especially in Austria, Switzerland, Italy, and so on. So basically, one-day races with something like 160 kilometers, [about] 100 miles, going through the mountains. I did this quite a lot back then. I learned and experienced [that] the longer the races are, the more climbing they have, the more I enjoy them <laugh> and yeah, the better my results were.

I came to bikepacking racing and ultra long distance cycling actually by accident. I was traveling with my camper in Spain and Portugal back in 2019. I was researching for any competitive bike events in Spain, but actually, they don't have this kind of gran fondo-like races. They only have classic criterion stuff around the church, like literally really short ones and really competitive. And the only longer thing I found was a race called the Transpyrenees , which was from east to west across the Pyrenees, something like a thousand kilometers.

It was actually a bit longer than what I meant with long races. Long races back then, I was thinking about 250, 300 kilometers, so something that still fits into a day. The thousand-kilometer race was quite a bit longer. It sounded appealing, it sounded interesting. So I signed up for it, and it was my very first race. Absolutely had no [idea] what to expect, but in the end, I won it. And the organizers were also a bit surprised. They then invited me to another event that they were running a couple of weeks later called Transibérica , which was basically three and a half thousand kilometers, the same format, but not across the Pyrenees but around the whole Spanish and Portuguese peninsula. It took me a few days, and I decided to get on this as well. I won the second one as well, and the rest is kind of history.

I got a bit into it, and it got worse and worse. And yeah, now I'm here having the Tour Divide as my race number 19 and doing quite well with all the other results in between.

Strava: You said the race organizers invited you to the Transibérica. How many weeks later was that?

Uba: It was [about] five weeks later.

Strava: So you just decided you're gonna race 3,500 kilometers (2,174 miles) five weeks later?

Uba: <laugh> Yeah. It took me two days, [to decide] I guess. <laugh>

Strava: I just wanted to clarify that 'cause that's fantastic. So, why the Tour Divide? What's so special about this race, and how long have you been planning this race attempt?

Uba: I decided [around the] end of last year. I have a long list of events and routes that I want to do. I thought it could be just the right year to tackle the Tour Divide because I was also asked if I wanted to join Unbound together with my partner BMC. For me, it [didn't] make sense to travel to the US just for Unbound. I wanted to see a bit more, and as it was that close together, it was a nice combination.

I mean, the Tour Divide had a big fascination [for] me because it's kind of the mother of all bikepacking races. It's the oldest one, it's one of the most prestigious ones.

I mean, it's amazing to see this red line across the whole US afterwards on the Strava map. It's just amazing to see what you have done on the map. And it's fascinating to see all the landscapes, all the variety, and just to take part in it. I think if you are into bikepack racing, there are quite a few events that, at some point, you have to do them. It's just a mandatory thing, a mandatory box that you have to tick. And this year was time for Tour Divide.

Strava: What was your goal going into the race? Were you just planning to win, or were you trying to set a new course record?

Uba: Both actually. I came with the clear and express goal to take the win and also to attack the route record. But I also stated at the same time I was well aware that like 20% of this goal is under my own control. This is a thing that I can influence, where I can prepare for, where I can train for, and where I can act on it. And the other 80% [depends on] what the trail allows me to do and what the outside conditions are.

That's very important for such a long race because so much can happen within two weeks. And we saw it, I mean, halfway we got stuck in the Great Basin in Wyoming, something like literally totally out of your control, you cannot do anything. You cannot even hike. We tried to hike, and we made a progress of one mile an hour, and if you are stuck in the middle and you have like 40 miles in each direction, you can calculate how long it will take you if you're making progress of one mile an hour. You simply have to be patient, and you simply have to deal with your goals, and you have to know that it's not just because you want to do it.

Strava: So speaking of the Great Basin, we have a few numbers: 12 hours, 3 fully grown men, and 1 porta potty. Can you tell that story for our audience?

Uba: Yeah. So Jens (Van Roost) and me we went together into the Great Basin. Justinas (Leveika), the third one, we were basically the front group of three. Justinas was two and a half hours back then, and Jens and me, we entered the Great Basin together. At some point, we got split up, and it started raining, and I saw on the ground his tire lines, and I saw he was still riding, and I was already pushing the bike. Between us, there was a difference of like five minutes or something.

Later on, I caught up with him again, and we kind of carried on together. You can imagine you push your bike, someone gets totally stuck because the tires and everything is full of mud, you need to clean it. And the other one gets an advantage of like 200 meters and gets stuck again. And so you leapfrog each other for ages. You can imagine making a progress of one mile an hour.

At some point in the evening, the third guy [caught up] to us. So he closed the gap of two and a half hours. Obviously, he was a bit back behind us. [Obviously] it dried up a bit, so he was able to ride a bit more of the route while we were crawling like [at] one mile an hour. I mean, even if you go [at] five miles an hour, you close the gap of two hours pretty soon. So he was a bit lucky on this one. So he closed the gap to us, and we were the three of us again.

We just carried on, and we decided we [had] to carry on all night because we had only minimal sleeping kit, like an emergency bivy with us. Out there in the Basin, there is literally nothing, just like the low bushes. There [are] no trees, there is no house, there is no shelter, there is no civilization, there is absolutely nothing. And so it became a bit serious and also a bit dangerous because if you stop moving, you soon end up in hypothermia. It was seven, eight degrees Celsius out there during the night. It was constantly raining, so we were already soaked, and you can imagine it’s not a cozy feeling. So we carried on and just tried to make the best out of it and hope for the rain to stop at some point, which actually didn’t happen.

At some point, I was a bit back, but I heard Jens screaming a bit far away, and I was wondering what happened, but well, it takes time to get there. And when I came there, I figured out he found this porta potty, and this was literally a miracle because it was in the middle of the Basin, and there was absolutely no reason for this thing to be there. There was nothing <laugh>. We don’t know why it is there. But it was the right thing at the right point. It was kind of a shelter, and there was no question if we were going to use it.

We took the essentials from our bikes which was basically the emergency bivies, some additional clothing, and some food. And then we went into this porta potty, and basically we were all three sitting on the toilet bench, which is one meter [wide]. It's one meter, and I mean, three guys don't really fit on one meter, but we [somehow] squeezed in there.

We made some funny agreements this evening and this night—for example, we said if someone needs to go to the toilet, he needs to go outside <laugh>. This is kind of the living room. I mean, it sounds disgusting and awkward, but we were sitting there on the toilet, and we were eating chocolate bars and chips and stuff because, if you are riding all day, you have to eat all day, and then you sit in this porta potty and eat stuff. It's a bit weird, but in this moment, it didn't feel to be a toilet. It felt just to be any kind of shelter. You forget [that] it's a toilet.

We were sitting in there from 11:00 PM to 9:00 AM because it was not only to wait out the night, but it was really to wait for the rain to stop. It was 6:00 AM when I went out for the first time just to [see] if things have become rideable again. I went out and just went with the bike for 20 meters and realized nothing [had] changed. It didn't make any sense because it was still cold out there, and it was still windy, so it didn't make any sense to continue. So we decided to stay for another hour, and we basically did the same test [to see] if the mud has somehow improved.

We tested it every hour, and at nine, it was the first time when we realized it's actually getting better. It stopped raining at seven, and sun came not directly up—it was still cloudy, but still, it was drying a bit. So at least we had the chance to push our bikes again and to move somehow, so we [began] at nine. But until then, we were just stuck within this toilet.

When I started at the beginning of the Basin in Atlantic City, I had planned something like worst case nine hours that it would take me to pass the Basin. In the end, it took 26. It was just insane.

Strava: <laugh> Wow, that's a hell of a story.

Uba: The toilet has actually become famous because all the people northbound and southbound that pass on the Tour Divide, they stop there, and they take selfies, and they put them into the Facebook group, and you literally see every day some selfies from people with sunshine and the best weather out there, and they're sitting in the porta potty and taking selfies with each other, and that's super funny. It's now probably the most famous toilet on the whole route.

Strava: <laugh> That's fantastic! So that sounds like it was a hard moment. Any other really difficult moments from the race that you want to share?

Uba: Well, I mean, it's a long ride. This one definitely was one of the biggest moments and one of the hardest things. But besides that, the first week was pretty rough because it was basically raining every day. With the rain, you get additional problems with the bike. I had to deal with some mechanicals. On day nine, I had kind of a serious breakdown and was sitting in the morning in my hotel room crying for 45 minutes because I thought everything was just against me: the bad weather, the mechanicals, the Basin. It's quite some drain on the mental strength there. It's part of this kind of racing and part of this kind of sport to get over it and to get control back. So yeah, there were some more hard moments, but I guess this one was the biggest ones.

Strava: That sounds brutal. But what about highlights? What were your favorite highlights from the course or your experience out there?

Uba: What's absolutely special: there were so many dot watchers out there. You meet them on the route, people that follow your dot on this map on the internet, and they come out to the route, they just cheer you on. That's absolutely fantastic.

The day after the Great Basin, we stopped at Brush Mountain Lodge, which is a lodge that's run by a woman. Her name is Kirsten, and she acts like a trail angel. She helps and accommodates each and every rider who comes through there. We ended up there in the evening, and she said, "yeah come on in, have a glass of water. Get rid of your cycling kit. We will give you a full wash. We will put it in the washing machine into the dryer."

So getting a complete new kit, basically fully washed half into the race, was fantastic. She made us pizza, and she got up at 4:30 in the morning to make us breakfast and pancakes. It felt a bit like a trap. It was really hard to leave this place in the morning. This was just a fantastic experience. The hospitality was just great. And all the people along the route cheering you—that was just awesome.

Besides that, an absolute highlight was definitely the landscape. It was my first time in the US. Racing in the US [and] seeing the whole route from Canada to New Mexico, how it changes, it's mind-blowing.

Strava: Speaking of the route, we had talked a bit earlier about course records. Can you tell me a bit about Koko Claims, what this addition is to the Tour Divide course, and how it affects it?

Uba: Koko Claims is a climb... I don't know if you can call it a "climb." It's a climb in Canada starting, I guess, after 160 kilometers. It's basically a super steep thing with, let's say, 15 to 20% [grade] on average. It's actually not a path that is rideable. It's a path that is full of loose rocks the size of the heads of children, like literally massive, massive, massive rocks. It's not super long, but you have to push and carry your bike up there. I actually killed my right shoe on the first day directly there—the Boa strap snapped. Later on, I had to fix my shoe with a zip tie, which was a bit annoying because while hiking, it always got off on the heel, which wasn't that helpful.

It's super exhausting to push a fully loaded bike up this climb, especially if you cannot step securely. It's not like on a path where you have a secure step. You always have to watch out where you step. And then it started raining when we were there, so even the rocks were slippery. It took something like two hours, 15 minutes or so on the climb. If you are up there and you think, "nice one, that's it, I made it," you haven't made the downhill, and the downhill is—I mean it's more rideable, but it's also super steep. And because it was wet, it was super muddy, and it was super slippery. So the downhill wasn't that much faster than the uphill. It's just a super crazy thing.

Koko Claims is probably the most brutal one, but there are a few more of those sections later on in Colorado.

Strava: My understanding is that's a fairly new addition to the course, and it wasn't included in the course when Mike Hall set his record in 2016—is that right?

Uba: Yeah, that's right. There was a discussion in the Facebook group ongoing about the actual record if we were still comparing apples with apples or if we have a banana in the meanwhile. Jay Petervary—who has done the Tour Divide, I don't know, so often—said the detour, which was mainly tarmac back in 2016, is probably something like four hours faster than the actual route over Koko Claims. So yeah, that's why there was some discussion ongoing about the record time and how comparable it really is.

[ Clarification : Based on Uba's account, Koko Claims was always part of the official course, but Mike Hall set the course record on a year when the course detoured around Koko Claims. Course detours are common from year to year due to extreme weather conditions, such as landslides or wildfires.]

Strava: You were only like four hours and change behind Mike Hall's incredible record. On a race that long, that's just incredible. So can you tell us a bit about your custom-built race rig? I was reading up on some of the race rigs, and yours is quite a bit different than the classic bike out there.

Uba: I decided to go with the BMC Twostroke, which is a hardtail mountain bike. That was the basis for my bike, and I started highly modifying it. For example, instead of the flat bar, I changed to a drop bar because I'm training mostly on the road bike and the gravel bike. With the flat bar, I just feel weird, and I know you have to feel really comfortable with your setup. So I changed the handlebar to a drop bar, which was much better for me to ride it. This was one major change, and then basically, I changed a lot of components, swapping them for more reliable, more durable, more lightweight components.

For example, instead of DT Swiss wheels, I added Beast Components wheels , which is a small manufacturer from Germany. The wheels are handcrafted, and they built me a set of wheels, including a Dynamo hub, which I used to run my front light and my battery charger.

I did quite some modifications on the setup to really find my perfect thing for the Tour Divide. Besides all the problems that occurred due to the weather, the mud, and, let's say, not so optimal conditions, I was pretty happy with everything I chose. It worked quite well over four and a half thousand kilometers. You definitely have some wear, and some stuff will break. It's a hard challenge not only for the human and for the body but also for the material. That's totally normal, but I was super happy with the setup.

Strava: In an email, you mentioned that all of your "free route" races were planned with the help of the Strava Route Builder. Can you tell us a little bit about how you use the Strava Route Builder and why you like it?

Uba: I use it basically since ages, since ever. I never used something else. I remember the times, probably it was back in 2016, '17, when you planned a route for a road ride, and the possibility to end up on a gravel road was quite high. It was good to see the whole journey, how the route planner improved over time with more and more people using it, with more and more data coming in and coming available to Strava.

It's handy to plan all kinds of rides because of your own heatmaps and the global heatmaps. The global heatmaps are especially useful if you try to plan a route in a region you don't know, then you can see, "okay, this is a quite well-frequented road or trail," or whatever. So it obviously means it's kind of possible. If it's a road ride, then you know it's not a main road, it's not a highway or something, but it's used by cyclists. And this helps a lot.

For example, last year I did the Transcontinental Race , which was from west to east across Europe. If you cross foreign countries in Europe, you can't know them all, and you can't know which type of roads are forbidden for cyclists and which kinds of roads are allowed. Therefore, the heatmaps are [very] helpful.

Now all the route planning is super reliable. You don't end up on a mountain bike trail with a road bike anymore. So that's quite good. You see the difference of a road route and a gravel or a mountain bike route just by the pattern [of the] line. So you know, maybe you add some short gravel section just to take a shortcut or something, and then you can look it up with satellite images, which are also included in the planner. You can have an [idea] of how it is there, how rough it is, and if it's a well-maintained gravel road or if it's like just a little trail or whatever.

That's a big toolset that I use quite frequently to plan my races. Half of them are like Tour Divide, where you just get a route and you just follow it. But the other half of the races, you get just checkpoints, and you have to connect them by planning your route yourself.

Strava: So that trans-European race is one of those where you had to plan your route all the way across Europe. Wow, that's incredible!

Uba: You spend basically hundreds and hundreds of hours just sitting in front of the Strava map, planning a route, figuring out which is the best way. Also, the different settings give me the shortest route or give me the route with the least elevation—those are settings that are [very] helpful to figure out which is a good compromise.

Strava: You had said earlier, I think in jest, that you had only ridden the Tour Divide to see it as one big line on the Strava map and that all of your rides are posted on Strava, which we love. Can you tell me a little bit about you're so passionate about Strava? What do you enjoy the most about it?

Uba: Over the years, it has become a really lovely community. It's really cool, on the one hand, for route planning. But I also use it a lot because I have all my data there to compare races I did, for example, with power output.

I can also check [out] upcoming events. For example, if the race from the year before is on the same route, then I can prepare and analyze data—on the Tour Divide as well. I just marked the segments like Koko Claims , and it helps me a bit to understand how long it will actually take me. So is it one hour? Is it four hours? This helps a bit, especially in the beginning for planning. On route, I just marked the big lines on my Garmin. So whenever I entered a segment, I knew, "okay, you will be busy here for the next four hours on this climb." It's good for the mind to not only see the kilometers because the kilometers can sometimes [mean] nothing, especially on the mountain bike. If it's a 10-kilometer climb, it can be one hour or it can be four hours. So to see the segment time is quite a good thing. So I use segments a lot.

I use the map for planning a lot. And Strava has become a very cool toolset to plan rides and to go on rides, which is super helpful for me. Also, I mean, there is a lot of fun on the platform with all the community and competition thing on segments or on clubs where you just see who has done the most kilometers for preparing for the Tour Divide or whatever. That's just fun.

Strava: What challenge is next on your to-do list?

Uba: Spending time on my couch.

Strava: <laugh>. Right, fair enough.

Uba: No, seriously. I have planned until the Tour Divide, which was my big goal for this year. Now it gets a bit calm, and then I will start with the planning process again. There is so much on my wishlist [that] I want to ride and so many ideas that I just need to start filtering them and plan them a bit and see what's coming next. And who knows? [Maybe] I will not wait for too long to get on my next project, but it's also important to get some rest for the body and for the brain to cool down a bit. Then let's take it from there.

Related Tags

More stories.

Runners to Follow at London Marathon 2024

Trail Running

Emma Stuart: The Farm Vet Winning the World's Toughest Races

Runners to Follow at Boston Marathon 2024

Your cart is currently empty!

Touring the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route vs. Racing the Tour Divide

Riding the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR) or racing the Tour Divide is a rite of passage for many bikepackers; it’s seen as the “Big One” in North America. Stretching 2,745 miles from Banff, Alberta to Antelope Wells, New Mexico, it loosely follows the Continental Divide through the Rocky Mountains on a series of dirt and paved roads. The fastest men can complete the route in under 14 days, while most people who tour it take six to ten weeks.

In 2018, I had the opportunity to tour the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR) with my husband Andrew Strempke. While we initially were attracted to racing, the rules of the event require solo, self-supported travel, and we wanted to ride together. And so we did, completing the route in 25 days. Four years later, in 2022, we both lined up to race the Tour Divide with the intention of completing the route within the constraints provided by the event. While we weren’t going to go out of our way to avoid seeing each other out on the route, the reality was that unless something went very wrong for Andrew, the chances of us riding near each other was fairly minimal.

Touring versus racing the route yielded two vastly different experiences. Racing tends to be more glorified by other people, but touring was just as satisfying, and in 2018, I believe it was the better choice for me at the time. There are benefits and drawbacks to each style of trip, and I feel lucky to have been able to experience both.

Rules, What Rules?

While the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route is open for anyone to ride under any style, signing up for Tour Divide means that you’re agreeing to pedal your bike from Banff to Antelope Wells in a self-supported solo fashion following the route mile for mile. On the other hand, touring provides the freedom to accept assistance from anyone, to share gear with as many people as you want, ride as fast or slow as you desire, and to detour around impassable roads or sections of the route that you’d rather not ride.

Touring: There are no rules! Choose your own adventure! The biggest determining factor that caused Andrew and I to choose touring over racing in 2018 was the Tour Divide’s rules about riding solo and self supported. Completing the route together was more important to use than officially completing Tour Divide. Andrew and I rode side by side the whole time, supported each other during low points, and kept each other entertained. We split gear to lighten our loads and deviated from the route a couple of times when following the route would have meant pushing through hours of mud, something we preferred to avoid whenever possible. We did want to complete our tour under our own power, so we didn’t ever get into a vehicle with the exception of a short road section that was under construction. The workers required us to take the pilot car until the end of the one-lane section of road. There was no one to question whether taking that ride in the pilot car invalidated our ride.

Racing: When I signed up for the Tour Divide, I agreed to abide by the rules of the race. There aren’t many, but the gist is that you agree to follow the entirety of the route in a solo self-supported fashion. With so much rain this year, making a turn onto a road I knew would be a sloppy mess when there was a perfectly good paved road that parallels the route was a bummer at times. That being said, knowing I was following the same route as all the racers, facing and overcoming similar challenges, and finding ways to make it through challenging conditions was rewarding in the end.

Riding self-supported also means carrying your own gear. When my dynamo light broke and I knew I’d have to spend more time charging electronics in towns, another racer offered me his extra battery pack and a light. While racer-to-racer support is typically tolerated, this definitely felt like a gray area and seemed a lot like sharing gear, so I chose to decline the offer, even though it would have saved me time.

Following the rules challenged me to solve my own problems and be mentally flexible when unexpected issues arose, which helped me to grow in my confidence as a bikepacker and solo woman traveler.

Counting Grams, Optimizing for Safety

The main difference in my gear between racing and touring was due to the fact that I couldn’t split the load with anyone during the race. Since I was going solo, it was important to maintain all of my own gear. I also had to be confident in using everything I carried. I wouldn’t have Andrew’s light or utensil or jacket if something happened to mine.

Touring: As we prepared for our tour, we decided we wanted to go light. We went with a minimal setup with no stove, no extra camp clothes, and one set of riding clothes. We split tools, a first-aid kit, and a two-person tent. Since we were on a 30-day timeline for our trip, including travel to and from the start, we had to cover ground quickly, and minimizing the weight on our bikes made a significant difference in the speed we could travel. The fact that we were able to share gear meant my load was actually lighter on the tour than it was racing.

Racing: When choosing gear for a race effort, it’s always a balance of being as light as possible while still being as safe as possible. I made some gear changes based on what I learned from the tour and my additional bikepacking experience. On the 2018 tour, I brought a 30-degree quilt and a foam pad and found myself too cold a few nights. For the race, I upgraded to a 25-degree sleeping bag and an insulated air pad. This setup actually ended up being too warm for most of the race and I woke up several nights in a puddle of sweat and drool, but it gave me confidence that I would be warm despite the wet and cold weather. I also brought more substantial rain gear after getting rained on during our tour in 2018 and finding that ultralight rain gear just doesn’t keep me warm or dry enough. I also chose to use a synthetic puffy rather than a down puffy. Synthetic insulation stays warm when it’s wet and down does not, but it also doesn’t compress nearly as effectively. I anticipated being soggy from rain or sweat for at least part of the ride, so the trade-off was worth it. I made sure all my tools worked and that I knew how to use them to fix common mechanicals.

Optimized for Speed…or Enjoyment

When people hear “touring,” they tend to automatically think you’re going slow and bringing the kitchen sink. That wasn’t the style of tour we were interested in, though plenty of people do that too. During our tour, we rode fast, but took it slow in towns to eat lots of food and get plenty of rest. In the end, my race pace was several days faster, not necessarily because I actually rode faster, but mostly because I just rode longer and stopped for as little time as possible, rushing through resupplies and meals.

Touring: Andrew and I completed our tour in 25 days, which is a pretty quick pace for a non-race effort. It felt good to challenge my body to go hard and cover ground quickly. I loved riding my bike all day and anyhow, we were on a timeline. Despite having a deadline to be back, not having the pressure of racing allowed us to slow down without guilt. One of our favorite stops during the trip was the Llama Ranch in Montana. We arrived in the afternoon and spent the rest of the day visiting with the owners Barbara and John rather than pushing on until dark. Later in the route, we stopped at Brush Mountain Lodge for several hours in the middle of the day where we ate pizza and drank beer, sitting and chatting for a few hours before continuing along the route. Being able to stop and spend time with Kirsten, who runs Brush Mountain Lodge was special, and she has become one of our best friends since then. Even though our tour took longer than the race for me, it was certainly not easy. No matter the pace, the Divide route will kick your ass some days.

Racing: My finish time during the race was 19 days and 16 hours. I probably didn’t actually ride much faster, but I rode longer each day and minimized stop time to complete the route in less time. Optimizing stop time and systems is one of my favorite parts of racing. It feels like free speed when you can get in and out of town or set up and tear down camp efficiently. I’ve tried to figure out exactly why I like bikepack racing and I honestly don’t have a great answer. I love challenging my body and the camaraderie of the other racers. I like making decisions under pressure and being forced to rely on myself to solve problems. Crossing a finish line knowing that I used my body and brain to the best of my ability to traverse an established route as fast as I could is a rewarding feeling.

Following The Route…Or Not

The Tour Divide route and the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route have some minor differences. When we were touring, we followed whichever one made sense at the time and deviated a few times when it made sense. When I chose to race, following the Tour Divide route mile for mile was required.

Touring: Making route choices was something extra we had to think about on our tour. We had the freedom to choose where we’d ride, but we also had to take responsibility for those choices if things didn’t work out. Our first detour from the Tour Divide route was around the hours-long hike-a-bike up Koko Claims in British Columbia, Canada. We had done zero hike-a-bike training and figured the risk of injury using untrained muscles wasn’t worth it. We talked to a local mechanic in Banff and he confirmed that going through Sparwood was a better choice for us and even gave us recommendations to take some new singletrack that paralleled the Great Divide Route. We had a blast on that section of trail and when we rejoined the route in Fernie, we saw racers with mud-covered bikes and bodies. Andrew and I looked at each other and agreed that we made the right call.

We didn’t escape every opportunity to hike through mud, though. Our longest mud stretch was on the legendary Bannack Road. We hiked for miles with our bikes on our shoulders or backs when rolling our bikes meant the tires collected mud and became bogged down in seconds. After encountering another rider at an intersection who told us the next section “was like something out of a nightmare” with more mud, it was an easy decision to take a paved short-cut into Lima. We agreed that detouring around long hike-a-bike sections with mud would help us maintain our sanity and have more fun on our trip. Detouring around spots that promised only suffering and misery didn’t make me feel any less like a route finisher at the end, but it definitely made for a more fun experience. I felt successful just getting from Banff to Antelope Wells under my own power.

Racing: To be a Tour Divide finisher, I was required to follow the published race route exactly. The times I went off route for supplies, I had to re-enter the route at the same point I left it. A wrong turn meant I would need to go back from where I deviated from the route to correct the mistake. When it was raining going over Togwotee Pass, I had to make the turn onto the notoriously muddy Brooks Lake Road to hike and ride through slop and snow instead of detouring on the paved road that paralleled it. When I’d toured the route, I’d taken the detour, so I knew exactly how nice the pavement was while I was trudging along at a mile an hour.

Participating in the race made route decisions easy. I just followed the line on my GPS and hiked when I needed to. If I wanted to finish, I had to stay on route. Since detouring around slow or potentially dangerous situations wasn’t an option, I also had to consider weather forecasts and my timing carefully.

During the tour, we didn’t really care how long resupply stops took. We typically sat down for a meal in a restaurant at least once a day and drank local beers. While I was racing, efficient resupplies were important. Limiting stop time is free speed and since I was demanding so much of my body, I didn’t drink beer along the way.

Touring: On our tour, we ate well and neither of us lost weight. Missing restaurant or grocery store hours didn’t mean we needed to keep moving to the next stop or eat a gas station burrito for dinner, we could just… wait. The pace of our resupplies was relaxed. We often took two-hour lunch breaks at restaurants and leisurely walked down the aisles of a grocery store or gas station until we had everything we needed. Salida became one of my favorite towns on the route after eating a huge barbecue Hawaiian pizza and salad at Moonlight Pizza and Brewpub. We slept in a hostel there and stayed up late talking with Continental Divide Trail hikers and other travelers. Our huge meals at cafes and conversations with both locals and other bike tourers added to our experience and gave us a flavor of the communities we were passing through.

Racing: Logistics and efficiency can be an interesting puzzle to figure out during a bikepacking race. Riding later into the night meant that hitting towns during business hours was more challenging. Before the race, I studied the towns and added business hours to a spreadsheet. I was aware of the times I might need to stock up on more food if I was going to potentially miss the next resupply.

When I was a few miles from a town, I would pull up my spreadsheet where I had calculated the distance, estimated time, and estimated calories needed to get to the next stop. I would start making a list in my head of the foods I wanted to get. “Potato chips, candy bars, some kind of gummy candy, pastries, burritos.” You know, all kinds of healthy stuff. I would run over that list in my head, picturing where I might find those things in the gas station or grocery store I was headed to. When I arrived at the stop, I would immediately start looking for an outlet if I needed to charge my electronics, then I would go into the store with my phone calculator in hand. I would walk down the aisles putting food into my basket, adding up the calories until I had enough. Then I would focus on the meal I wanted to eat right then. Normally a vegetarian, I made some exceptions to my normal diet, eating chicken at times when I couldn’t find another good protein source in a gas station.

I ate while I packed up my bike instead of sitting down at a restaurant with one exception. I arrived in Sargents, Colorado, feeling nostalgic. It’s where the Western Express ACA Route crosses the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route. Having been there with Andrew both on our cross-country tour in 2012 and our 2018 tour got me all sappy and I felt like I needed to sit down, reset, and get some real food in me.

Companionship or Solitude

I feel lucky to have shared the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route with Andrew. We made countless memories that we still reflect on today. During the race, I found companionship, but my time with other racers was brief and I spent most of the ride by myself. This might sound lonely, but I also really value alone time and moments spent by myself in beautiful places can be equally as moving for me as moments in those places with another person.

Touring: Andrew and I rode the entire route side by side. It was really special to have shared the experience with the most important person in my life. We were in tune with each other’s needs, moods, and when to provide a gentle reminder that maybe the other needs a snack. When conditions were tough, we kept each other’s minds busy by playing 20 questions. We made decisions as a team about where to stop for food and where to camp for the night. We had both of our brains to deal with mechanicals and make decisions about any reroutes.

In general, riding together tends to be slower. You’re going whatever pace the slowest person at the time is going and end up taking more breaks since you’re dealing with two people’s needs. We typically rode about the same pace and if one of us needed a break, the other was patient. We both wanted the other to feel good and enjoy the ride.

Andrew and I are fortunate that we get along really well, but we did have our moments. I know that Andrew was pretty upset with me when I lost my rain jacket on a rough descent one day just before sunset. (I have since learned that everything that I want to keep goes in a zipper pocket). He sprinted back up the road to go find it while I rode much more slowly behind him. Fortunately a kind racer picked it up so he didn’t have to ride too far up the climb. Then there was the time when Andrew insisted on taking photos of the Montana/Idaho border sign in a thunderstorm. As someone who hates thunderstorms, all I wanted to do was ride down the pass and became increasingly frustrated as Andrew insisted on taking several selfies.

Racing:

While the Tour Divide is set up to be ridden solo, many racers end up forming small groups to ride with. While I rode mostly alone, I did have some time riding alongside other racers, typically for a short time. I would see other racers in towns and when we took breaks. Spending time with people briefly once a day was enough social interaction to keep me sane. I’m a pretty introverted and independent person. Extensive alone time doesn’t bother me and is something I look forward to. Still, every time I would run into my good friend and fellow racer Zack, who was also on a singlespeed, we would chat and share a few miles. The emotional boost provided by those interactions was undeniable.

Andrew was also racing the Tour Divide this year. We anticipated not seeing each other unless something went wrong for him. We agreed not to communicate about the race at all while we were out there. We sent a few voice memos with funny stories. I told him about the time I ate jalapeño chips and they went down the wrong pipe and I gave myself a bloody nose coughing them back up. We promised to not say, “I miss you,” because it just makes us both sad. But I did miss him, and being alone definitely reminded me how much I love Andrew, my friends, and my family.

One of the hardest moments during my race was leaving Brush Mountain Lodge. Kirsten wasn’t planning to be there during the race, but she was. I had already stopped in Savery just 15 miles down the hill for an hour, so I didn’t have more time to spare to spend time with her and my good friend, Jolly, who was helping at the lodge. I left in tears, wishing I could have stayed. I was comforted by the thought that I could come back to the lodge after I was finished.

Traveling solo meant that I generally had to deal with my fears alone, but after a particularly scary lightning experience outside of Pie Town, I was glad to be able to decompress with other bikepackers and hikers at the Toaster House in Pie Town. Just a few miles out of town, I’d felt electricity running through both of my hands through my handlebars and jumped off my bike and got under a small clump of juniper trees. I set up my tarp to stay dry and sat in the lightning position until the storm passed. I was pretty hysterical. After that, I decided to stay at the Toaster House in Pie Town. I felt like I needed indoor accommodations and to talk to other humans to feel okay to go back out into the elements the next day. Jefferson, the host, made a hot meal for me, the other bike tourers, and the CDT hiker staying there. I spent a lot more time talking with them than I normally would have during a race. Talking about our experiences on the route and what life is like outside of bike touring and racing helped me to reset and calm down.

Outside of the emotional support of companionship, I had to be confident in my ability to fix my bike, make good choices in a fatigued state, and be safe on my own. I haven’t always felt confident bikepacking solo, but as I’ve gained more experience I’ve become more comfortable. One of the only times I felt weird being alone is when I saw a man on the side of the trail who was loading a gun. He asked, “Are you alone?” I went ahead and told him that there are other riders right behind me, which is my typical answer for any man who asks me that question.

Sharing the Experience

I wanted to document both our tour and my race. It’s so easy to forget little details if you don’t record or write them down. Documentation takes extra effort, but I’m happy that I did it during both trips.

Touring: On our tour, I laid in my sleeping bag and typed out a blog post with pictures from my phone every night so that our friends and family could follow along, and now I can look back and remember something from each day of the tour. Andrew also took an action camera and made a video about our trip. I found that we were less likely to record our low moments riding together since it’s a bit rude to put a camera in your partner’s face when they’re having a bad time.

Racing: Documenting my race was important to me. I carried a GoPro and posted occasional Instagram stories. Race documentation by outside media crews during the Tour Divide has been met with controversy in recent years, so aside from wanting the footage for myself, I wanted to show that there is a self-supported way to tell my story. My Instagram stories and GoPro footage is certainly not as beautiful as a professionally documented film, but it’s raw and I like it that way. Most of my documentation was done while I was pedaling, and I put together the GoPro footage when I was recovering after the race.

It’s interesting to think about the ethics of posting on social media in the context of self-supported racing. I inevitably got encouraging messages whenever I posted. Knowing that my friends were watching definitely made me want to continue to ride my best. Ultimately I decided that since people generally have access to a smart phone with social media, I wasn’t giving myself an unfair advantage by posting on Instagram. Some may disagree, but I feel good about what I chose to do during the race. I was intentional about my posts as to not solicit advice or support from other people and maintain the self-supported nature of the ride.

Romance, or Lack Thereof, of Camping

For a lot of bikepacking trips, finding a beautiful camping spot can be a highlight of the trip. When racing, I went to bed after dark and any spot was as good as the next. We put a little more intention into camp spots while touring, and I slept better during our tour knowing there was another set of ears next to me.

Touring: Andrew and I slept most nights in our two-person tent. We’d start looking for a spot to camp as sunset approached. We didn’t care so much about whether we slept somewhere scenic, but we had higher standards than when I raced. We got a couple hotel rooms when the weather was wet. I admittedly stole Andrew’s puffy jacket on nights when I was cold! We typically woke up with the sun and quit pedaling at sunset, giving us plenty of rest. We rode past dark one night in New Mexico to beat the heat which turned out to be the only time we saw a bear during the entire trip. Aside from those few miles, we saw the whole route in the daylight.

Racing: My standards for camping while racing were pretty low and I almost always rode past sunset. I didn’t mind riding in the dark since I had seen the route in the daylight before. Riding at night is a new way to experience the same place differently. I love looking up at the stars on a clear night and seeing animals who are normally sleeping during the daytime. Since I was riding more in the morning and evening, I had way more wildlife sightings during the race than during the tour. I saw several bears, one little fuzzball of a bear cub, a mountain lion, three moose during the day and three at night, countless deer and pronghorn, and a handful of other smaller animals.

When it was time to choose a spot to sleep, I made sure the location I chose was dry and not too high in elevation. If there was snow, that was a hard no. In New Mexico, the monsoons were so intense that it was difficult to find a spot that didn’t look like water was running there at some point. The worst camp spot I chose was on the side of the highway under a tree next to a bunch of garbage. It was one of the only dry-ish spots I could find.

I enjoyed indoor accommodations twice during the race, at the Llama Ranch in Montana and at the Toaster House in New Mexico. Those nights felt very luxurious. If you count pit toilets, I had a few additional nights inside in bear country. I camped with other riders for two of the nights. Aside from that, I slept under my tarp, in my bivy, by myself.

Getting to Antelope Wells

During both trips, a big goal was finishing the route. I made different decisions during both trips to meet my goals. While I was racing I had to make these decisions under pressure.

Touring: The top goal for our tour was finishing the route. While we were on a timeline, we took a couple of shorter days in the beginning while our bodies got used to pedaling long miles. It wasn’t a big deal to stop early because there was no pressure of racing. When Andrew’s Achilles tendons started to flare up a few days in and we saw a sign for a brewery in the middle of nowhere, we stopped and drank beer even though we had just taken a lunch break. This gave his ankles a much needed rest, allowed us to reflect on all the riding we’d done so far, and gave us a Montana cultural experience. Being able to make choices without the pressure of racing undoubtedly helped us make decisions that got us to Antelope Wells.

Racing: Finishing the route was also a goal for the race, but more than that, I wanted to go faster than I did during our tour. If for some reason I wasn’t able to go that pace due to body or bike issues, I probably would have considered scratching. It just wouldn’t be worth putting my body through the stress if I couldn’t meet my goal. This was definitely a change in attitude for someone who used to value finishing at all costs.

During the race, I let the speed of others dictate some of my decision making. The day I got into Colorado, I was the third woman. I was six hours behind Ana, the second woman, and 14 hours behind Zoe, the first woman. It was clear to me that I had no chance of winning without making a huge move. I thought to myself, “All I have to lose is my sleep and sanity.” That night I rode much later than I had on previous nights, slept for two hours, and got really close to Ana. But the decision to sleep so little meant I was worthless the next day. All the people riding the same pace as me before caught back up to me by the end of the day. The pressure of racing guided me toward sacrificing sleep when I should have taken better care of my body. When I found out Zoe quit that day I felt pretty dumb for letting her distance ahead of me dictate how much I slept. I re-learned the lesson that I need to take care of myself to ride strong and making decisions based on how another person is riding is usually a mistake. Had I kept riding and sleeping the way I should have, maybe I could have stayed closer to Ana in the end.

Feeling Part of Something

Humans, even the introverted ones, are all social creatures, and our brains are wired to want to be part of a community. During both trips, I felt part of a group of bikepackers riding their bikes from Banff to Antelope Wells. When we were touring, we definitely felt different than the racing group.

Touring: While we started our tour on the same day as the Grand Depart of the Tour Divide and were around racers much of the time, it felt like we were doing something different than they were. It wasn’t a positive or negative thing, just different. After finishing, I definitely felt part of a group of people who have completed the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route, and when we meet people who have accomplished this feat, we have an instant connection.

Andrew and I were fortunate to be able to help out at Brush Mountain Lodge in 2021. During that time, we talked with racers and hundreds of people touring the route. Often the tourers would say, “I’m just touring.” When I heard that, I tried to tell them that you don’t have to say “just.” I totally get it though. Andrew and I said the same thing when we were touring and people in towns asked us if we were racing. Sometimes they would treat us differently than racers. There were places with banners for only racers to sign or some people would become uninterested after they found out we were “just” touring. That wasn’t the case everywhere. Kathy from Ovando greets every bikepacker who comes through town with the same enthusiasm regardless of racing or touring status.

Racing: When I sign up for a Grand Depart event, I feel a connection to the racers around me. It helps when I’m walking through snow, riding through rain, or staying up late into the night knowing there are other people out there doing the same. I have always experienced this as a positive thing until this year. There were 15 rescues in the Canadian Flathead in the first few days of the race. There were reports of racers using hotel towels to clean their drivetrains. Later in Montana I ran into a local man trying to get home but couldn’t because photographers following the race blocked the road. When I heard about the rescues, poor manners at the hotel, and saw the behavior of the photographers, I was embarrassed to be part of the race. It made me angry that people participating in the Tour Divide were having a negative impact on the communities the route traverses. I’m hopeful that future Tour Dividers can look at this year as a learning experience and that future racers give more respect to the route, the power of Mother Nature, and the people along the route. That being said, for the majority of racers who completed the route, the challenging weather conditions this year provided an unforgettable experience and swapping stories with other racers will be something we can do for years to come.

As a woman racer, I also feel a strong connection to other women on the route. All of the racers I saw were men, though I saw several northbound touring women and always stopped to say hi and have a brief conversation, usually about the route ahead. While I didn’t see other women racers after the first day, when I got to Colorado, I did my best to chase down Ana. Ana managed to stay ahead and went on to win the women’s race, 15 hours ahead of me. Even though we never met, somehow I felt like I knew her since I traced her tracks on the trail. When I got to meet her later in the summer after she crushed the Colorado Trail Race with a second-place finish, I considered her a friend instantly.

Racing or Touring

I’m so grateful Andrew and I had the opportunity to tour the route together in 2018. We did have limited time, so it was a fast tour, but we never felt rushed and didn’t have to follow the rules of the race. We shared gear and deviated from the route when it made sense. Our resupply stops were relaxed and we ate lots of huge meals at cafes along the route. We stayed well rested and well fueled. When I thought I only had one opportunity to experience the wonder of the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route, I chose to ride it as a tour and I would 100% make that same choice again.