Column: Mookie Betts’ season of sacrifices paved the way for the Dodgers’ World Series run

- Copy Link URL Copied!

The defining moment of the Dodgers ’ season went by almost completely unnoticed.

That’s because the importance of the moment wasn’t measured by what happened. Rather, it was measured by what didn’t happen.

When Mookie Betts returned to right field in mid-August , he didn’t complain. He didn’t brood. He didn’t stop playing like Mookie Betts.

Instead of causing the kinds of problems that have derailed countless other teams with championship aspirations, Betts used his influence to create a culture of sacrifice that has become a trademark of the Dodgers, who will take on the New York Yankees in the World Series starting Friday.

“When guys like that do it,” manager Dave Roberts said, “everyone else has to fall in line, as far as whatever roles, wherever they hit in the order, if they play or start or don’t start.”

During the past few weeks, Dodgers players forfeited time with their families to spend more time with one another. Freddie Freeman played on a sprained ankle . Reliever Brent Honeywell threw live batting practice to slumping hitters.

Freeman said of Betts’ team-first mindset, “It just carries over to the rest of the team.”

In the retelling of this story, Dodgers officials say they never doubted that Betts would relinquish his place at shortstop and move back to right field. It would be more accurate to say they were hopeful.

Betts had always told them he would do whatever was best for the team. However, in his previous four years with the Dodgers, what he was asked to do generally coincided with what he wanted. In this case, they were about to ask him to do something he might not want to do.

Which would explain why, as Betts approached his return from a broken hand in early August, Roberts initially said he would remain the team’s shortstop .

A six-time Gold Glove Award winner in right field, Betts had an obvious affinity for playing the infield. The workaholic Betts had thrown himself into relearning a position he last played regularly in high school by taking grounders before every game. The broken hand in mid-June halted his progress.

By the time Betts was close to being activated from the injured list, the Dodgers knew they wanted him back in right field. At this point, Betts hadn’t played in seven weeks, costing him experience at his new position. The Dodgers had added infield depth in the likes of Tommy Edman and the since-departed Nick Ahmed. Miguel Rojas was also expected to return soon from an injury.

Hernández: Shohei Ohtani is ‘finally’ in the World Series. How he made it happen

Shohei Ohtani suggested the Dodgers pay him only $2 million a year and defer the remainder of his annual $70-million salary. It was basically a blank check to fortify the roster.

Oct. 21, 2024

Betts looked determined to remain the team’s shortstop, as he resumed fielding grounders as soon as he was medically cleared to do so. Team officials knew he could point to how he became the shortstop in the first place because they overestimated Gavin Lux’s ability to play the position. They knew he could point to how he already made a substantial sacrifice by switching positions in the lineup with Shohei Ohtani , who in his absence had taken over his preferred leadoff spot. They knew he could point to how he was, well, Mookie Betts.

“When you have a guy that has a name and just the accomplishments and talents about him, like someone like Mookie does, [and] he wants to be the leadoff hitter, he wants to play certain positions and you tell him he has to go somewhere else, you always worry about that causing conflict,” infielder Max Muncy said.

However, Muncy added, the players knew Betts wasn’t a typical superstar.

“There was never going to be any question from any of us about Mookie,” Muncy said. “We knew that he would do whatever it takes to help the team win. He’s proven that time and time again.”

Motivated by move to shortstop, Dodgers veteran Mookie Betts is on a tear

Mookie Betts’ move to shortstop has sharpened his focus on the game, especially at the plate so far this season for the Dodgers.

March 31, 2024

Muncy raised another point.

“Him moving to the infield this year was about helping us win as much as anything,” Muncy said.

Unlike other players, Freeman noted, Betts just happened to be talented enough to play a new position.

“The man can do anything he wants,” Freeman said. “I think he’s one of the best athletes I’ve ever seen on the field. He’s one of the only people that could probably do what he’s done throughout the course of the year.”

The players were right. When Roberts addressed the situation, Betts agreed to the change.

“You want to win, that comes first,” Betts said at the time. “That’s all I care about.”

Complaining, Betts said, would have been “a very selfish thing.”

“That’s not who I am,” Betts said. “I’ve preached this from the very beginning, and I always will.”

He has lived up to his words. In addition to providing the Dodgers with a premium glove in right field, he has also shined as their No. 2 hitter, punishing opponents who elect to pitch around Ohtani.

When the Dodgers signed Betts to a 12-year, $365-million contract extension before the pandemic-shortened 2020 season, president of baseball operations Andrew Friedman said they were betting on Betts the person as much as they were Betts the player. Clearly, they made the right call. Their reward: a fourth World Series appearance in eight years.

More to Read

Reinvigorated Mookie Betts provides the spark in Dodgers’ blowout win over Padres

Oct. 9, 2024

Dave Roberts wants struggling Mookie Betts to embrace a different mindset

Oct. 7, 2024

Mookie Betts got ‘lost in the process’ this year. Can it lead to better playoff success?

Oct. 3, 2024

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Dylan Hernández is a sports columnist with the Los Angeles Times. Before that, he was the Dodgers beat writer. Hernandez grew up in South Pasadena and graduated from UCLA in 2002, after which he worked at the San Jose Mercury News for five years.

More From the Los Angeles Times

‘We’ve all been battle-tested.’ Dodgers’ relievers rely on each other to seal wins

Oct. 27, 2024

Mike Scioscia on Fernando Valenzuela: ‘You could see his leadership in the clubhouse’

Shaikin: Yoshinobu Yamamoto proves there is still strength in Dodgers’ starting pitching

Hernández: Dodgers could still win World Series without Shohei Ohtani, but no one wants that

Most read in dodgers.

Plaschke: Ouch-tani! Shohei Ohtani’s injury places World Series win at risk

Oct. 26, 2024

Dodgers win Game 2, but will Shohei Ohtani injury complicate World Series path?

Dodgers defeat Yankees in World Series Game 2, but Shohei Ohtani sustains injury

Shaikin: Joe Davis reveals the influence Vin Scully had on his Freddie Freeman World Series call

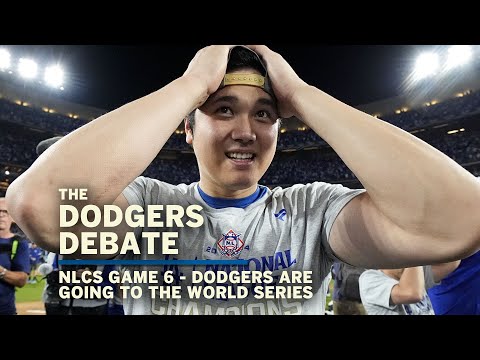

Mookie Betts' best moments of the NLCS

Take a look at the some of the biggest and best moments of Mookie Betts during the National League Championship Series

- Los Angeles Dodgers

- Mookie Betts

- team featured

Mookie Betts knows he can’t save baseball. He just plays like he can.

ATLANTA — As one of the patchy-bearded faces of a game that once represented Black progress and excellence in this country, Mookie Betts occupies a rare position in the modern professional sports landscape: a Black American baseball superstar. Betts feels a responsibility accompanying his unicorn status, but he also recognizes the forces that make him such a rarity are bigger than he is.

Baseball’s hold on the Black community has loosened over generations, to the point that vanishing representation among Black Americans in the sport has gone from noticeable to concerning.

But while his home runs on uppercut swings and his leaping outfield catches serve as a live-action billboard to anyone who might find inspiration, the Los Angeles Dodgers star doesn’t pretend to overstate his influence.

“I’m not trying to come here and be the savior for baseball or for the culture,” Betts said.

Betts understands the random circumstances that contributed to his being 11 seasons into a career with a Hall of Fame trajectory. He didn’t learn to love baseball until he was getting paid to play it. Like many from his generation, the soon-to-be 32-year-old’s first choice would have been a career in basketball. But any pursuits of hoops had limitations.

“I’m 5-9, 170 pounds. Not many guys like me make it to the NBA,” Betts said with a chuckle. Baseball “kind of chose me.”

A three-sport standout at Overton High in Nashville, Betts never developed an affinity for one sport over the other — until the Boston Red Sox, enamored with his talent and potential, selected him in the fifth round of the 2011 draft and offered a $750,000 bonus, nearly $600,000 above scale at the time.

Since then, he has helped lead two of the game’s most storied franchises to World Series titles, has been one of two Black Americans to be named MVP over the past decade (the New York Yankees’ Aaron Judge is the other) and, in recent years, has persuaded one of the most conservative of sports to look inward about becoming more empathetic and inclusive.

“I’m just being myself,” Betts said after a game last month, a dark brown snapback cap resting backward on his bald head and a gold Figaro link chain and another modest one with a miniature plastic ball and Dodger blue bat dangling from his neck. “I can only do the part that I can do — and do it to the best of my ability.”

Support at home

Diana Collins gave birth to Mookie after a night out bowling with friends and gave him a name — Markus Lynn Betts — with initials that indicated her vision for his future. But guiding MLB to MLB wasn’t that simple. Betts excelled as the city’s best basketball player and the state’s best baseball player and bowler. His parents plucked his nickname from former NBA star Mookie Blaylock, and basketball allowed him to play with his closest friends.

“Baseball was just something that we all just kind of did,” said Betts, who stays connected to hoops by sponsoring an AAU basketball team from Nashville, Team Mookie. “We take pride in trying to do everything. It really just kind of happened. It took me a little time to learn how to play one sport that I wasn’t a huge fan of.”

From the beginning, Betts’s journey through baseball had one constant: His parents had his back.

Collins fielded Betts’s first Little League team at age 5 after coaches determined the kid who needed Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles suspenders to hold up his pants was too small to play for them. As Betts got older, his talent was apparent to his father, Willie. But the opportunity wasn’t always there. They encountered a few situations in which coaches sought to use their teams as vehicles to showcase their own sons. That meant Betts rode the bench. That meant Willie took Mookie elsewhere.

“A lot of kids quit because they ain’t got nobody to fight for them,” Willie Betts said. “Mookie had me.”

Collins helped fund Betts’s efforts in travel ball by raising money through carwashes or by working concessions at Tennessee Titans games — whatever it took.

“Makes all the difference in the world,” Betts said. “My parents, they’re amazing. And they really kept me into everything, whether I loved it or not. They loved going to watch me play. And I loved seeing the joy that was brought to them.”

Though Betts considered playing college baseball at Tennessee, Collins remembers a conversation in which she spelled out his options and mentioned that attending school would force him to write papers. Betts told her he was done writing papers, but he set out to write his own history in the game.

“I don’t half-ass anything,” he said. “To be good at something, you really got to dive in and understand what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. You got to love [baseball] because there’s so much failure that comes with it. If you don’t grow a true love and passion for the game, man, this thing will beat you down.”

Almost famous

America’s pastime is past the time in which it holds significant cultural relevance. MLB has done its part to speed up the game, in hopes of luring younger viewers too buried in their phones to pay attention otherwise, but the sport has never fully recovered from a performance-enhancing drug era that eroded trust. Elite players still earn stratospheric salaries, but baseball’s lagging popularity has made it difficult for any player, of any background, to gain mainstream fame.

The 12-year, $365 million contract extension Betts signed with the Dodgers in 2020 has provided generational wealth for his family and allowed him to chase other business pursuits. Betts, his wife, Brianna, and their children, Kynlee and Kaj, are in a new Lego commercial that features rapper Pusha T, and before a mid-September game against the Braves, he joked around at Truist Field with R&B singer Usher.

But Betts’s celebrity in baseball doesn’t carry the same cultural currency as an equally accomplished player in the NFL or the NBA. LeBron James or Patrick Mahomes has a higher probability of being name-dropped in a hip-hop song or debated incessantly on talking-head shows. Betts recognizes the differences but doesn’t expect a change anytime soon.

“Nothing I can do about it,” he said. “I’m not embedded in the culture like that. I wish I was. Maybe one day I will. I’m just embracing who I am within the game and the culture that I bring is the culture that I bring.”

‘It takes more than Mookie’

Betts’s most powerful statement about race in baseball is encased under a spotlight as part of dozens of artifacts and memorabilia in the new exhibit at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. The black-and-blue T-shirt with the airbrushed message “We Need more Black People at the Stadium” has become a symbol for the current plight of Black Americans seeking continued relevance in a game that once excluded them. Betts wore it before batting practice at Dodger Stadium ahead of the 2022 All-Star Game.

Beforehand, Collins worried about how the message would be received. She wondered whether her son was prepared for backlash from those who might be confused or alienated, or if bad-faith actors would mangle it into something other than a plea for action. “You don’t want to offend anyone,” she told him.

Betts let his mother know he was ready for anything. It had to be said, and given his standing in the game, he had to be the one to say it. From the time he had made his debut in 2014 with the Red Sox, Betts had a top-step-of-the-dugout view of the dwindling presence of people who looked like him in the clubhouse, on the field and in the stands.

“I wasn’t afraid of what was going to come,” Betts said, reflecting on the moment two years later. “You do it for the positive side of it. I just want to bring more Black people to the stadiums, to the minor leagues. Baseball is a beautiful game. Times have changed and I think we just got to adapt with it.”

Betts said “it’s pretty neat” that his shirt, designed by streetwear brand Bricks & Wood, made it to the Hall’s “Souls of The Game: Voices of Black Baseball” exhibit. But the change he sought then, and is seeking now, has yet to gain traction.

“You see it, but you try not to see it,” Collins said of a league in which just 6 percent of the Opening Day rosters this season were Black Americans. “Mookie was like, ‘If I do my part and be the best that I can be and help encourage them, then hopefully down the road, somebody else can come along with me and we can make a difference.’ It takes more than Mookie, and it takes more than a mindset to change that.”

The reasons for the decline — and what can be done to reverse the trend — are “way above my pay grade,” Betts said. Even while playing for one of MLB’s two Black managers, he only needs to look around to feel more isolated in a game he said “means the world to me.” Though he has managed to find comfort in almost any environment, Betts looked down to the carpet in the clubhouse and admitted, “I change more coming here than going home.”

The Dodgers finished with the best record in baseball but it was an unusual regular season for Betts. He started the season batting leadoff and playing shortstop for the first time since high school, an experiment that wasn’t always pretty — “It was hard,” he admitted. After a pitch broke his left hand, forcing him to miss six weeks, he was moved to the No. 2 spot in the lineup behind Shohei Ohtani, baseball’s $700 million man, and moved back to right field, resulting in the Dodgers cutting Jason Heyward, one of just two other Black Americans on the roster at the time.

Betts was either averse, or didn’t feel informed enough, to take stances in Boston but hasn’t shied away from using his voice since being traded to the Dodgers in 2020. Disappointed in MLB’s response to the George Floyd protests, he posted a video on Instagram about racism in America and knelt during the national anthem before his first game in uniform. A month later, he refused to take the field for another game, after the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wis. His teammates joined him, and MLB postponed other games because of his gesture.

It’s a role some Black American players have reluctantly signed up for, while others have embraced what comes with being one of the few to advance to the highest level. Willie Betts said his son is free of any burden “because Mookie knows he can play.” Willie Betts added that his son has maintained a strong reputation in the game — Mookie is a nominee for the Roberto Clemente Award this season — because he has heeded the one message Willie consistently gave him: “You play the game, but don’t act a fool.”

A revived pipeline of promising Black American talent in the minors and the presence of younger stars in the majors, including Cincinnati Reds pitcher Hunter Greene, provide some hope, but it will take time. Betts is ready to welcome them, whenever they arrive. Knowing what the game has provided him, Betts doesn’t want to see Black Americans abandon baseball or vice versa. His shirt might be in a museum, but the message still applies.

“All of us have a purpose. And I’m not exactly sure what mine is,” he said. “Baseball will just be one thing that I’ll be known for. Hopefully it’s not the only thing I’m known for. I don’t care if kids play baseball. I just want them to have opportunities to become a lawyer or a GM or whatever it is. That’s kind of where my brain is at. But if I can get more kids playing, that’s even better.”

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The Yankees intentionally walked Mookie Betts, setting up the left-on-left matchup with Freeman. The team that has won Game 1 has gone on to win the World Series 24 of the last 30 times.

Column: Mookie Betts’ season of sacrifices paved the way for the Dodgers’ World Series run. Mookie Betts follows through on an RBI double during the eighth inning of Game 6 of the NLCS against ...

Mookie Betts on experiencing World Series in LA. October 24, 2024 | 00:01:55. Reels. Mookie Betts describes what it means to him to play in the World Series and do it in Los Angeles. Los Angeles Dodgers. Mookie Betts.

Mookie Betts' best moments of the NLCS. October 21, 2024 | 00:00:56. Reels. Take a look at the some of the biggest and best moments of Mookie Betts during the National League Championship Series. Los Angeles Dodgers.

Team. Markus Lynn " Mookie " Betts (born October 7, 1992) is an American professional baseball outfielder and shortstop for the Los Angeles Dodgers of Major League Baseball (MLB). He has previously played in MLB for the Boston Red Sox.

“Mookie had me.” Collins helped fund Betts’s efforts in travel ball by raising money through carwashes or by working concessions at Tennessee Titans games — whatever it took.