A Walking Tour of the Best Brutalist Architecture in London

Architecture & Design Editor

Brutalism has a bit of a bad rep, but our architectural tour is here to change that – swap the conventional sights of London for some concrete beauties on your next visit. Here’s how to spend the day seeing the city in a whole new light.

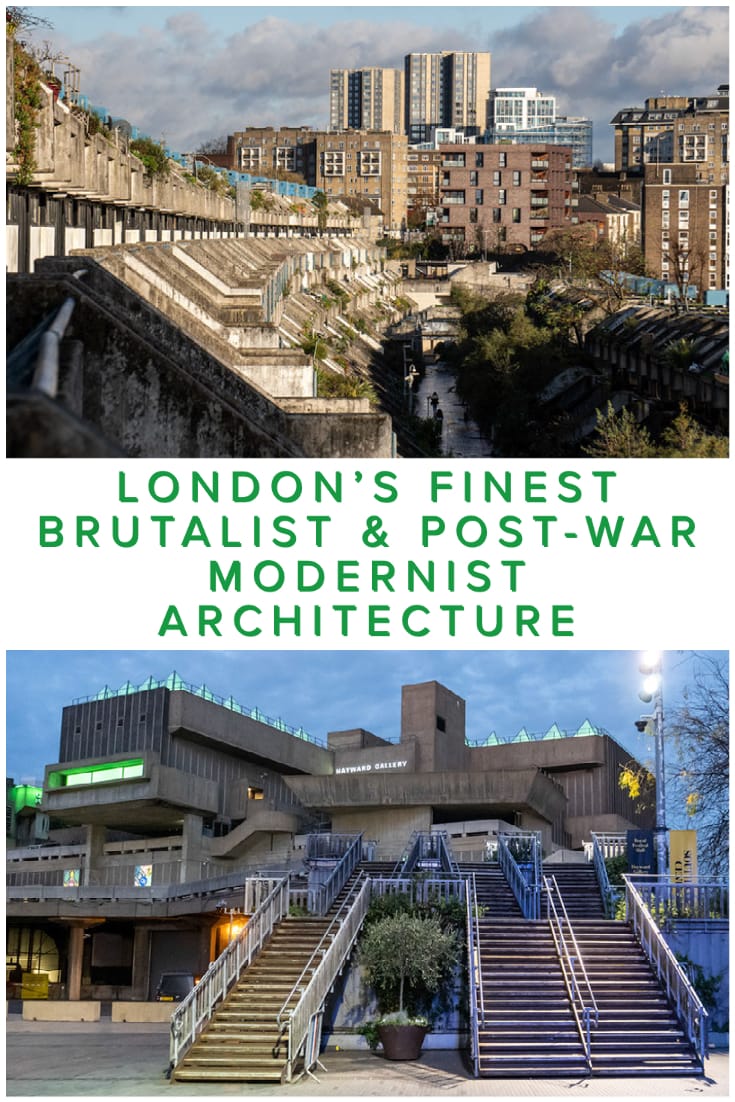

1. southbank centre.

Most people take a stroll along London ‘s Southbank to visit the Tate Modern or Shakespeare’s Globe , but there’s plenty of other architectural gems along this stretch. Start at the Southbank Centre , a world-renowned destination for the arts that was erected in 1951 to celebrate the Festival of Britain . The site is home to several important venues, including the Royal Festival Hall, the Hayward Gallery and the Queen Elizabeth Hall, all of which hold varying events such as comedy stand-ups, variety shows, musical performances, intellectual and educational programs, and festivals.

Royal Festival Hall

Hayward Gallery

The Hayward Gallery is one of the world’s leading contemporary art galleries. Since it opened in the summer of 1968 with an exhibition by Henri Matisse , it has played a crucial role in presenting work by some of the world’s most significant artists. It was recently closed for two years in order to restore the 66 glass pyramid roof lights, which were based on a concept by sculptor Henry Moore. The multi-million pound refurbishment was completed in January 2018, holding a major show of Andreas Gursky’s work.

Become a Culture Tripper!

Sign up to our newsletter to save up to 500$ on our unique trips..

See privacy policy .

Queen Elizabeth Hall

Recently renovated, Queen Elizabeth Hall has a wonderful roof garden with stunning views and is open daily in the spring and summer months and free to visit. Fun fact: you might notice an unusually placed ‘boat’ on top of Queen Elizabeth Hall. The ‘Room for London’, designed by Living Architecture is actually available to stay in on occasions.

There are plenty of food trucks along the riverbank for a low-key lunch or pre-performance bite before heading along to the National Theatre, as well as many on-site restaurants . For something a little bit special, and great views over the Thames, try Skylon , which serves up quintessentially seasonal British dishes.

2. National Theatre

Designed by the architect Denys Lasdun , the National Theatre has divided public opinion since it opened in 1976. In 2001, a Radio Times poll featured Denys Lasdun’s building in the top five of both the most hated and the most loved British buildings. A neighbour of the Southbank Centre, the theatre may seem like a large hunk of concrete on the surface, but once you discover the attention-to-detail and groundbreaking construction methods behind it, you’ll come to realise its beauty. To get a real understanding of why the National Theatre is such an important icon of Brutalism, take up one of the ‘Concrete Reality’ architecture tours .

3. The Macadam and Strand Buildings, King’s College London

Crossing Waterloo Bridge, it’s worth stopping by and gazing up at the King’s College Macadam Building, which was built by Troup, Steele & Scott with E.D. Jefferiss Mathews acting as consultant. Construction started in 1972 and took three years to complete. The building on Surrey Street houses King’s College Student Union, with its six storeys balancing on top of a two-storey podium.

Just around the corner on The Strand is the aptly-named Strand Building, which is again part of the college. The 1970s building has recently been involved in some contentious plans to knock down four adjacent period properties, in order to make way for a new teaching building that will ‘blend in’ with the Brutalist one.

4. Salters’ Hall

To get here, you could take a leisurely half-hour stroll along Fleet Street, the former home of London’s newspaper industry, passing the Royal Courts of Justice and St Paul’s Cathedral on the way before turning up Cheapside and along London Wall. Located on Fore Street, the old Salters’ Company headquarters, built by Basil Spence, is a very rare example of a post-war livery building, and was completed in 1972. Notable for its distinctive ribbed and knapped concrete, the hall is now Grade II-listed and has recently been refurbished by architect De Metz Forbes Knight, which won planning consent for the £8.5 million project.

5. Barbican Centre and Estate

Saving the best until last, you can’t miss the Grade II-listed Barbican Centre, which is Europe’s largest multi-arts and conference venue and one of London’s best examples of Brutalist architecture. It was developed from designs by architects Chamberlin, Powell and Bon as part of a utopian vision to transform an area of London left devastated by bombing during the Second World War. It took over a decade to build and was opened by the Queen in 1982, who declared it ‘one of the modern wonders of the world’.

Its stunning spaces at the heart of the Barbican Estate have made it an internationally recognised venue, set within an urban landscape acknowledged as one of the most significant architectural achievements of the 20th century. The best way to tour the Barbican Centre and surrounding estate is to book the Barbican’s 90-minute walking tour . Walking along the highwalks, elevated gardens and trio of high-rise towers, you’ll learn more about the construction, design and influence of the estate, along with surprising and rarely seen sights and discoveries plus little-known insights into this unique architectural endeavour.

KEEN TO EXPLORE THE WORLD?

Connect with like-minded people on our premium trips curated by local insiders and with care for the world

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel - and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way. That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Culture Trips, Rail Trips and Private Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

Culture Trips are deeply immersive 5 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and 4-5* accommodation to look forward to at the end of each day. Our Rail Trips are our most planet-friendly itineraries that invite you to take the scenic route, relax whilst getting under the skin of a destination. Our Private Trips are fully tailored itineraries, curated by our Travel Experts specifically for you, your friends or your family.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm - and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet. That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

See & Do

The 41 best things to do in london.

How the Metaverse can help you plan your next trip

Bars & Cafes

The best bars in london for stylish nights out.

Food & Drink

The best international afternoon teas in london.

Places to Stay

Five london hotels to familiarise yourself with.

The Coolest Hotels in London

Guides & Tips

Must-visit attractions in london.

Pillow Talk: Between the Sheets of the Beaumont, Mayfair

Top European Cities for a Plant-Based Foodie Fix

A High-Rollers Guide to a London Staycation

A West End Performer’s Guide to London With Sam Harrison

Winter sale offers on our trips, incredible savings.

- Post ID: 1005704

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

- Corrections

London’s Best Brutalist Architecture: 5 Amazing Buildings

London’s Brutalist architecture isn’t universally liked. However, its bold use of concrete and strong angular forms are impossible to ignore.

When people think of Brutalist architecture, they often think of the residential complexes common in many ex-soviet countries. Brutalism, however, emerged in Britain in the 1950s during the process of reconstruction after world-war II. It remained popular, especially for public buildings and social housing, until the 1970s, when it became increasingly associated with totalitarianism. In this article, we explore some of London’s most distinctive Brutalist masterpieces.

Before Diving into London’s Best Brutalist Architecture: What Is Brutalism?

What makes a building Brutalist? Architectural styles aren’t the kind of things one can define precisely. The notion of a style is more like a shared family resemblance between the examples of the style.

One feature that many Brutalist buildings share is their angularity. Brutalist buildings don’t ebb and flow, their edges aren’t softened. In his essay ‘ The New Brutalism’ , originally published in Architectural Review in 1955, Reyner Banham identifies a second common characteristic: the use of large structural elements as design features. Instead of diverting attention away from the functional inner-bones of the building, they are made to stand out.

A third thing that is characteristic of Brutalist buildings is their use of materials. In a break from the earlier Bauhaus movement , materials aren’t hidden, they are showcased. This is best illustrated by the use of exposed, unpainted concrete; although other materials such as brick or steel are also common. Materials are shown for what they are, concrete is shown as concrete-y, steel is steely. In Reyner Banham’s words:

“Whatever has been said about honest use of materials, most modern buildings appear to be made of whitewash or patent glazing, even when they are made of concrete and steel. Hunstanton appears to be made of glass, brick, steel and concrete, and is in fact made of glass, brick, steel and concrete.”

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription, 1. trellick tower and balfron tower – erno goldfinger .

Balfron Tower in Poplar was completed in 1967. Erno Goldfinger, a Hungarian émigré, was commissioned by London County Council to build the tower as part of the government’s drive to increase housing supply. Goldfinger was a devout believer in the potential of high-rise living. In fact, he and his wife Ursula moved into the penthouse apartment at Balfron Tower upon its completion.

Balfron Tower is perhaps best known for its distinctive separate service tower, connected to the living block every third floor, which contains the lifts, launderette, and communal recreational rooms.

Residents of the tower were initially apprehensive about high-rise living, but Ursula Goldfinger’s diaries from when she lived there showed that, once moved in, people’s attitudes softened. She wrote: “ Many tenants who live low down say they would like a flat farther up – I have heard no tenant who lives high up say they would like a flat lower down.”

Trellick Tower, containing 217 flats and 5 maisonettes, was built 5 years after Balfron Tower. All of the apartments have their own balcony, giving residents expansive views over London. The use of one large tower, instead of a series of smaller blocks, provided ample space for children’s play areas at the bottom of the tower, which could be seen from the balconies.

Like Balfron Tower, it also bear’s Goldfinger’s distinctive trademark: a separate service tower containing the lifts and connected to the building every third floor. Unlike Balfron Tower, however, in the later development the service tower is crowned by a distinctive boiler house. Although it was called the ‘Tower of Terror’ by the press when it was built, the apartment block has become a much loved feature of the local area. In 2021, for instance, the local council had to abandon plans to redevelop the estate after resistance from residents to the loss of outdoor space and children’s play areas.

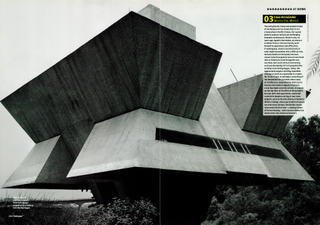

2. Lecture Centre, Brunel University – Richard Sheppard

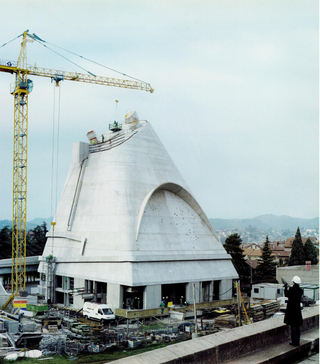

Brunel University commissioned Richard Sheppard, Robson and partners to design their Uxbridge Campus. At the time, Brunel University (named after famous nineteenth-century engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel) was one of the largest engineering schools in Europe. The lecture theater building is a perfect example of Brutalist architecture . Its bold form and use of coarse concrete make the building tower over the surrounding plaza.

The building is perhaps most famous for being featured in Stanley Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange , where it houses the Ludovico Medical Facility where the main character, Alex DeLarge, undergoes aversion therapy. Alumni of Brunel University, however, will probably remember it differently, as the building is still in use today as a lecture theater and conference venue.

3. The National Theatre – Denys Lasdun & Partners

Completed in 1976 after a 13 year wait, the National Theatre occupies a prime spot on the south bank of the Thames. Its three horizontal terraces are constructed out of concrete, and jut out imposingly over the plaza below. Inside, however, these features are softened by the fact the concrete was set in raw timber, giving the building an organic element, and the use of thick deep purple carpets and dark wood benches.

The imposing architecture of the Theatre is not universally liked. It frequently appears in lists of both London’s most hated and most liked buildings. Most notoriously, in 1988 now King Charles the III described it as “a clever way of building a nuclear power station in the middle of London without anyone objecting.”

The theater is still in use, staging a variety of productions including both Shakespeare and new plays by contemporary play-writes. The foyers of the building are open and accessible to the public, and were once described as ‘the nation’s living room’. They currently host exhibitions, a café and bar, and bookshop. As well as theater-goers, the building also attracts skateboarders due to the covered areas outside the building and the proximity to the south bank skate-park.

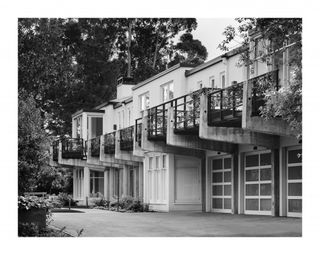

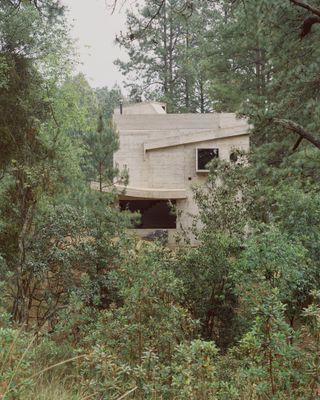

4. Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate – Neave Brown

The Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate was commissioned by Camden Council, and built by Neave Brown of the Camden Council’s Architect Department. Neave considered himself a modernist architect however, the Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate is done in the brutalist style. Construction started in 1972 and took 6 years.

The estate contains 520 apartments built from unpainted, board-cast, concrete; as well as a school, community center, youth club, and gardens. The blocks back on to the nearby train lines, shielding the interior of the estate from the noise of the trains. Each home has private outdoor space, and many of the apartments open onto pedestrianized walkways.

The estate has all of the central features of Brutalist architecture. The raw unpainted concrete puts the construction material center stage; and the bold angular forms of the apartment blocks set it apart from the Victorian housing that surrounds it. Unlike other brutalist architecture of the time like Trellick Tower, however, it doesn’t tower above the surrounding area. In this regard, it pays homage to the terraced houses that preceded it.

As with most Brutalist architecture, it is not universally liked. Some residents describe it as being like Alcatraz, whereas others relish the fact the estate was the first council built housing estate to be given Grade II listed status.

5. Dawson’s Heights – Kate Macintosh

Dawson’s Heights, East Dulwich, is built on top of a hill, offering panoramic views of central London in the distance. Designed by Kate Macintosh, Dawson’s Heights was the young architect’s first commission. Dawson Heights was built at a time of massive council-backed building projects aimed at clearing slums and providing decent and comfortable homes for working-class people. Although originally council owned, many of the flats are now privately owned.

The development includes almost 300 flats, divided into two staggered blocks, both of which overlook a shared garden. The result has an Escher -like quality. Macintosh objected to the uniform, monotonous blocks that had started to be built across the UK, choosing instead to create a multidimensional building inspired by Edinburgh Castle. Each of the flats also has a private balcony, providing fresh air, privacy and fantastic views to the residents. Macintosh managed to justify the extra cost of providing balconies by making them serve a twin-function as fire-escapes. By removing a glass panel, residents can move across onto neighbor’s balconies to distance themselves from the fire.

Dawson’ heights doesn’t have the trademark Brutalist use of concrete, being made instead out of brown bricks. It does, however, have many of the other characteristics of brutalist architecture: remaining faithful to the material it is built from, and the use of bold angular forms.

References

Young, Jack. (2022) The Council House. Hoxton Mini Press, London.

Barton, Emma (Ed). (2020) Atlas of Brutalist Architecture. Phaidon Press, London.

Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Turbulent Life of a Philosophical Pioneer

By Joseph T F Roberts PhD Political Philosophy I am currently a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in Law and Philosophy at the University of Birmingham. Prior to this, I completed my Ph.D. in Political Theory at the University of Manchester, where I wrote a thesis on the moral permissibility of Body Modification Practices and, specifically, whether or not we have the right to pursue them without being interfered with by others. My current research focuses on the limits of consent, embodiment, and the regulation of recreational drugs.

Frequently Read Together

Forging The Modern Aesthetic: The Bauhaus Movement Explained

7 Facts You Need to Know About Brutalism

M.C. Escher: Master of the Impossible

London: Brutalist Architecture & History Walking Tour

About the activity

Discover post-war Brutalist architecture on a guided shared group or private walking tour of Central London. Learn about the history of Brutalism and photograph notable examples.

- Free cancellation Cancel up to 24 hours in advance for a full refund.

- Instant confirmation & Mobile tickets Receive your ticket right away. Use your phone or print your voucher.

- Private tour Avoid crowds with an exclusive experience. (depends on selected option)

- Live guiding English

- Start time - Available tomorrow 10:00 AM

- Duration 2.5 hours

- Walking tour

- Public transportation costs

- See notable Brutalist buildings in the heart of Central London

- Learn about the use of concrete in engineering and architecture in modern times

- Hear about global events that influenced London's post-war architecture

- Snap striking photos of famous Brutalist buildings such as the National Theatre

- Take an educational and informative tour to discover an alternate side to London

Description

See London's most significant Brutalist landmarks with a walking tour. Loved by some, loathed by others, see rugged urban fortresses which serve excellent examples of Brutalism, the most striking and dramatic architectural style of the 60s and the 70s. Explore the central neighborhoods of London with your guide. Hear more about the history of post-war architecture and the increased use of concrete. Discuss Modernist monumental architecture, as well as its cultural, social, and environmental impact in the world. Find out about key characters in European Modernism, as well as the global events that influenced and informed London's post-war landscape. Admire or recoil at notable examples of Brutalism that you will see, such as the Institute of Education and the National Theatre. Learn more about the ongoing struggle among local authorities, preservation societies, and residents on how best to use these distinctive buildings in the future.

- The tour uses the tube once for a short journey. Please ensure you have enough credit for one trip within Zone 1

- The walk may be postponed or canceled if weather conditions are unfavorable

- The interiors of buildings are not visited

Shared Group Walking Tour

Private walking tour, reviews & ratings, top 5 similar activities in london.

London: Buckingham Palace, Westminster Abbey & Big Ben Tour

Embark on a walking tour of central London and discover 3 of the city's most iconic landmarks. Learn about the fascinating history of each place, with skip-the-line access to Westminster Abbey.

- 4.5 hours • Skip the line • Guiding available • Available tomorrow

London: The Great British Rock and Roll Music Walking Tour

Walk in the footsteps of rock and roll royalty on a music walking tour in London. Visit the locations where rock and roll legends played, recorded, performed, drank, caused trouble and hung out.

- 2 hours • Guiding available • Available tomorrow

London: Jack the Ripper Small Group Tour

Prepare to be gripped by the chilling tales of Jack the Ripper's reign of terror. Our Jack the Ripper Tour will transport you back to the sinister streets of Victorian London, where the mystery and intrigue of this infamous killer await.

- 2 hours • Guiding available • Available today

London: Harry Potter Locations Walking Tour

Visit different Harry Potter location sites and see buildings that inspired the books by JK Rowling on a walking tour of London. Attempt to enter the Ministry of Magic, shop for butterbeer, and more.

- 3-6 hours • Private tour • Guiding available • Available today

London: Experience the Changing of The Guard

Get closer to the world-famous Changing of the Guard ceremony in London on a private or small-group tour led by a local. Discover the significance behind one of the most iconic British traditions.

- 105 minutes • Private tour • Guiding available • Available from April 10, 2024

Frequently Asked Questions

Prices & booking.

- Participant 0-99 years { clearTimeout(timer); timer = setTimeout(function(){ window.livewire.find('wsUqQrvCkFLJ4WBPAnnE').emit('personChanged', value, 'adult'); }, 1000) })"> 0 ? 1 : 0" class="relative -mr-10 inline-flex justify-center items-center w-10 h-10 rounded-full bg-white text-gray-900 text-sm hover:text-gray-500 focus:z-10 focus:outline-none focus:shadow-outline-blue active:bg-gray-100 active:text-gray-700 transition">

- Mexican Peso MXN New Zealand Dollar NZD Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Złoty PLN Romanian Leu RON Singapore Dollar SGD South African Rand ZAR South Korean Won KRW Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF Turkish Lira TRY UAE Dirham AED Ukrainian Hryvnia UAH

Something went wrong!

- The Lifestyle

A guide to the best brutalist architecture in London

London's brutalist buildings have long been the subject of much contempt and controversy. But thanks to a resurgence of interest in recent years, these post-war concrete behemoths are being seen in a new light, and receiving the appreciation they deserve. If, like us, you can't get enough of brutalism's clean lines and dramatic forms, scroll on for our guide to the very best brutalist architecture in London.

Best brutalist buildings in London

Barbican Centre and Estate

The Barbican Estate is one of London's most iconic and best-known brutalist buildings. Designed by architects Chamberlin, Powell and Bon as a way of transforming an area of London that was heavily bombed in World War Two, it took over ten years to build and was finally opened as an arts centre in 1982. Its exterior may give it the air of a forbidding fortress, but inside the thick concrete walls, it's teeming with culture and features extensive greenery and water.

Trellick Tower

Ernӧ Goldfinger's Trellick Tower is a West London landmark that's loved and loathed in equal measure. It was completed in 1972 and combines a main block of social housing with a service tower, connected via covered walkways. While it initially suffered due to poor maintenance and high crime rates, the 1980s saw its revival. Today, Trellick Tower's spacious, light-filled apartments are highly sought after due to their impressive views.

National Theatre

Notably described by Prince Charles in 1988 as "a clever way of building a nuclear power station in the middle of London without anyone objecting", Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre, which opened in 1976, is one of London's most polarising brutalist buildings. We just so happen to be big fans of the dramatic concrete statement, which carefully balances horizontal and vertical elements for an attractive assemblage of interlocking terraces. An £80m refurbishment by Haworth Tompkins in 2015 has kept the National Theatre looking good as new.

Royal College of Physicians

Denys Lasdun's lesser-known design, the Royal College of Physicians, stands out as a brutalist beauty amidst the palatial Regency architecture of St. Andrews Place in Regent's Park. Opened in 1964, it remains one of London's most important post-war buildings, famed for its pioneering use of mosaic clad concrete as well as a unique 'Moving Wall' that can be hydraulically lifted to unite or sub-divide an interior hall.

Centre Point

Central London's Centre Point, designed by George Marsh of R. Seifert and Partners, was unveiled in 1966 as one of the capital's tallest buildings. It controversially remained vacant for many years, earning it the nickname 'London's Empty Skyscraper', but has recently been transformed by Conran & Partners into a block of luxury modern apartments. Its distinct '60s style, characterised by bold geometric design and a honeycomb facade, makes it an architectural icon of London's contemporary skyline.

Macadam Building, King's College London

Situated amongst the resplendent 19th century buildings of The Strand, King's College's Macadam Building is one of the lesser-appreciated examples of brutalist architecture in London, but certainly shouldn't be overlooked. Designed by Troup, Steele & Scott along with consultant architect E.D. Jefferiss Mathews, and completed in 1975, the building impressively balances six storeys on top of a narrower two-storey podium.

Discover the brutalist Escobar House in Buenos Aires

Related Articles

Bourbon: Excellence in every glass

Elevate your dog's walks with these top-notch leads

A definitive guide to leather accessories

For over 12 years our community of 1m+ have been discovering the latest art, automotive, interiors, fashion and architecture in our free bi-weekly emailer ..

We'll keep you up to date.

Brutalist Tour

Walk London's most iconic Brutalist locations, from residential, to office and anything in between. Meet the city's concrete beauties in person and feel, see and touch the roughness that has earned them their reputation while learning the most relevant facts and fun stories of each place.

This tour has two options:

- Morning tour : 3h. Includes sights such as Barbican, King's College, The Brunswick Centre, Royal College of Physicians and Centre Point.

- Evening tour : 3h. Includes sights such as National Theatre, Southbank Centre, Hayward Gallery, Trellick Tower and Alexandra Road Estate.

Should you be planning to see both, a combined day trip can be arranged.

- Starting Point : Barbican (Morning tour), National Theatre (Evening tour)

- Duration : 3h. It finishes around Regents Park (Morning tour) or South Hampstead (Evening Tour)

- Language : English, Spanish and others upon request

Tour prices are dependent on numbers and the type of experience you are after. It can vary from £20-30 per person for the individual tour or £140 for a private tour . Please get in touch to discuss them further.

HOW TO BOOK

Send an email to [email protected] with:

- Subject: Brutalist Tour

- Date : When would you like to do the tour?

- Number of adults / children

- Any must-see places on your list?

- Means of transport : Is walking ok? Other options such as private car are available.

- Share Share on Facebook

- Tweet Tweet on Twitter

- Pin it Pin on Pinterest

- choosing a selection results in a full page refresh

- Food & Drink

- Things To Do

- Beyond London

London's Top Brutalist Buildings

Do monolithic slabs of roughly-finished concrete make you go weak at the knees? If so, you are going to enjoy this roundup very much indeed.

Brutalism’s bold, monumental, and on the whole, deadly serious style remains controversial, years after it was replaced by Post-Modernism and the Neo Vernacular style.

There is a little confusion as to who first coined the term Brutalism — Swedish architect Hans Asplund claims to have used it in a conversation in 1950, but its first written usage was by English architect Alison Smithson in 1952. The term was borrowed from pioneering French architects and refers to unfinished or roughly finished concrete (beton brut in French).

The following are a mix of familiar and somewhat less well-known Brutalist buildings in London. Please add your own personal favourites in the comments section below as there are happily (or not, depending on your standpoint) many examples of this uncompromising architectural style in our beloved capital.

Brunel University Lecture centre Nearest tube: Uxbridge then take a U3 bus. Map

This imposing mid-60s building famously starred as the ‘Ludovico Medical Facility’ in Kubrick's legendary film A Clockwork Orange . For this reason alone it is well worth a pilgrimage. It has also appeared in various TV series including Spooks, Silent Witness and Inspector Morse. Its jutting geometric forms mark it as a classic example of mid-period (or ‘Massive period’) Brutalism.

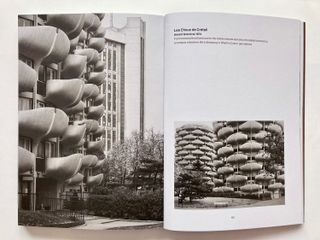

Brunswick Centre Nearest tube: Russell Square. Map

Designed by Patrick Hodgkinson, this grade ll-listed residential and shopping centre has made several TV and film appearances and even had a song written about it by 90s indie ‘supergroup’ Lodger. The impact of its striking service towers and flying buttresses is softened by the sky blue and cream colour scheme, lending the whole development an almost breezy air.

Royal College of Physicians Nearest tube: Regents Park/Great Portland Street. Map

Sir Denys Lasdun designed the graceful and discreet geometries of this building. Never a card-carrying Brutalist, he presented a softer version of its often hard-nosed style. Surrounded by the splendid neo-classical terraces of John Nash, The Royal College of Physicians holds it own and manages to be both elegant and entirely of its time.

Centre Point Nearest tube: Tottenham Court Road. Map

How many times have you walked past this Grade ll listed London landmark and never given it a second thought?

Designed by Richard Seifert and completed in 1966 it was described by the Royal Fine Art Commision as having an ‘elegance worthy of a Wren steeple’. Note how the gentle v-shaped window mullions soften and add interest to this slender, Massive period tour de force.

The swish Paramount restaurant and bar occupies the top floors and has outstanding views of London. There is also a free viewing gallery. Phone up beforehand (0207 4202900) to let them know that you’re coming.

The Barbican Nearest tube: Barbican/Moorgate. Map

This sprawling (and remarkably easy to get lost in) late Brutalist development houses the wonderful Barbican centre, the largest performing arts centre in Europe and home of the London Symphony Orchestra. The accompanying Barbican Estate gives you the impression of being in a Brutalist theme park. Though voted ‘the ugliest building in London’ in 2003 by some dullards, the tranquil waterside setting, complete with fountains and swaying reeds, renders it positively romantic. The soaring towers and vast concrete volumes are also nicely contrasted by the warmly-coloured tiled paving.

A highly recommended 90 minute architectural tour is available.

Trellick Tower Nearest tube: Westbourne Park. Map

Designed by the wonderfully-named Erno Goldfinger (Ian Fleming appropriated his surname for the Bond villain, much to the architect’s chagrin), the equally loved and loathed Trellick Tower rears up majestically from west London and has featured extensively in television, music promos and film as well as appearing on mugs, bookends and t-shirts. The approach via Westbourne Park tube can take you through the charmingly named Meanwhile Gardens; apart from being pleasantly verdant, the view from the gardens gradually reveals Trellick Tower in all its splendour.

If you like what you see, check out the Brownfield Estate (nearest tube All Saints DLR, Map ), where you can see three iconic Brutalist structures — Balfron Tower, Glenkerry House and Carradale House — for the price of one.

Southbank Centre complex and National Theatre Nearest tube: Embankment/Waterloo. Map

This bold cultural behemoth has been compared to a nuclear reactor and an overgrown car park, and is often as confusing to navigate as an Escher painting. However, its complex and imposing concrete volumes have many fans and there is an enormous amount to see and do in and around it. Have a good look at the texture of the concrete and you will see a variety of finishes, including the imprints left by the wood ‘shuttering’ (moulds) when the concrete was cast in situ. The Skylon restaurant, housed on the first floor of the Royal Festival Hall has wonderful views over the Thames and is recommended.

Camden Town Hall Annexe Nearest tube: Kings Cross. Map

Apparently this distinctly curvy (for Brutalism) and attractive building has been earmarked for redevelopment (i.e to be demolished) so go and have a look at it while it still stands.

Built during the late period of Brutalism, The eye-catching curved corner windows illustrate how architects were beginning to move away from the more block-like structures of the Massive period.

Alexandra Road Estate Nearest tube: Swiss Cottage. Map

A high-density, low-rise housing project, this Grade ll listed building is mounted on rubber pads to minimize noise from the busy railway alongside it. Presumably the relative scarcity of windows on the side facing the tracks, greatly adding to its monumental appearance, was also designed with noise reduction in mind.

The best view of this arresting stadium-like aspect is from Abbey Road, just to the west of the estate as it crosses the railway lines.

Institute of Education , Bedford Way Nearest tube: Russell Square. Map

Completed in 1979, Sir Denys Lasdun’s enormous structure puts the ‘massive’ into Massive period Brutalism. The huge concrete service towers are highly characteristic of Lasdun’s style but here they are elegantly married with long lines of dark tinted glass windows which hark back to the earlier, pre-Brutalist, International style. A gorgeous hunk of a building, the classic view of it is from the south west corner of Tavistock Square, just to the north.

Ministry of Justice Nearest tube: St James’s Park. Map

Truly colossal, Basil Spence’s building was accused by Lord St John of Fawsley of ruining St James Park. However, it has a particularly impressive aspect when viewed from the southern area of the park. Unmistakably Massive period brutalist, the cantilevered projection near the top is said to have been inspired by medieval Italian fortresses according to Alexander Clement in his excellent book, Brutalism: Post-war British architecture .

St Giles Hotel Nearest tube: Tottenham Court Road. Map

If you are an out-of-towner and are looking for somewhere to stay in London, how about the thoroughly Brutalist St Giles Hotel? It’s handily located for visiting the many Brutalist buildings in central London. The building comprises four large cantilevered towers with the windows cleverly arranged on sawtooth projections allowing lots of natural daylight and a good view from every room.

If you fancy getting up-close and personal with a few of the buildings, a short tour is easily possible. Start at King's Cross to admire Camden Town Hall Annexe on Euston road opposite the station, then take a short walk south to the Brunswick Centre on Hunter Street. Just west of this is London University on Bedford Way. Afterwards make for Tottenham Court Road and head south along it; you will pass St Giles Hotel on your left shortly before arriving at Centre Point.

Text and photographs by Toby Bricheno; @TobyBricheno

Last Updated 24 May 2012

Ramadan And Eid Events In London 2024

The Best Places To Find Bluebells In And Near London This Spring

The Top Exhibitions To See In London: April 2024

16 Spring Day Trips From London: April 2024

Londonist in your inbox.

Get London news, inspiration, exclusive offers and more, emailed to you.

- I would also like to receive the Best of Londonist weekly roundup

Thank you, your preferences have been saved.

Follow londonist, report a problem.

Something wrong with this article? Let us know here.

Thank you, your feedback has been noted.

museumofbrutalistarchitecture.org

Museum of Brutalist Architecture MoBA

Museum of brutalist architecture.

Visit the museum and experience a Brutalist building

Arrange a visit or a tour of MoBA ‘s exhibition at the museum which is hosted in the Hall for All

MoBA is located at the ‘HALL FOR ALL’ in Acland Burghley School’s Brutalist Community, Culture and Heritage Venue

Located in North London it supports creative events, exhibitions and performance

Explore Brutalist buildings

Immerse yourself in local heritage, arts and culture by visiting our [STORIES ] collections. Find out about latest activities, events and exhibitions. Get involved in [WHAT’S ON] , use our interactive maps to [EXPLORE] Brutalist buildings in your area, and learn more about Brutalist architecture by visiting the museums [INSIGHT] zone.

MoBA aims to stimulate awareness of Brutalist architecture to amplify its cultural and heritage value and to explore, record, and celebrate the communities that live near or within these buildings

[ EXPLORE ]

Brutalist buildings can be accessed via the interactive digital map. Look for the Yellow Pin, use your smartphone to track your position and find incredible Brutalist buildings in your area

Immerse yourself in local heritage, arts and culture by visiting our [STORIES ] collections. Look for the Black and Yellow Pin

Access knowledge and resources about Brutalist architecture. Explore brutalist architecture using MoBA ’s interactive learning tools and download FREE learning resources

Explore the Collections, learn more about the social heritage of Brutalist architecture, immerse yourself in stories, and discover more about its history and impact

Access knowledge and resources about Brutalist architecture

Explore brutalist architecture using MoBA’s interactive learning tools, see what people’s interpretations are of Brutalist architecture, see MoBA’s simple definitions and access free downloadable learning resources. You can even test your knowledge taking the Quiz

MoBA’s Learning and Insight Zone

Explore brutalist architecture using MoBA’s interactive learning tools, see what people’s interpretations are of Brutalist architecture, see MoBA’s simple definitions and access free downloadable learning resources.

EXPLORE OUR COLLECTIONS, STORIES AND INSIGHTS

Interactive Brutalist Building Map

Use the map to plan your walking trail of Brutalist buildings. Select the TRAIL menu for suggested routes. Search by category of project and click on map to explore more about each location.

Heritage, Culture and Community Stories

Use the interactive map to explore Heritage, Culture and Community [STORIES] that are related to or inspired by brutalist buildings. We collect stories, insights and experiences such as [Multimedia, Audio and Video], [Sketches, Photography and Drawing], [Music, Poetry, Dance and Theatre], [Storytelling and Narration] and any community or personal creative output which has a connection with Brutalist buildings.

Visit the Museum

Visit the museum at Acland Burghley School’s ‘ Hall for All ‘ Venue. You can see related information about the Brutalist building including the original architects model.

What’s On

Visit the ‘Hall for All’ events calendar to see current events and exhibitions as well as opportunities for immersive experiences and performance.

Get Involved

The museum team supports education and learning opportunities, prepares and run workshops and supports people from all backgrounds, abilities and ages to participate.

Look for MoBA QR codes in buildings, on Trails and around the museum and link to more information about Brutalist architecture.

ABOUT THE MUSEUM OF BRUTALIST ARCHITECTURE MoBA

MoBA is based at the ‘Hall for All’ a Community, Heritage and Arts venue in North London which supports creative events, exhibitions, and performance.

The venue is located within the grounds of Acland Burghley School and is an outstanding example of a 1967 Brutalist multi purpose space, hexagonal in plan form and designed by Howell, Killick, Partridge and Amis, one of the country’s foremost post-war architectural practices.

The Museum of Brutalist Architecture was founded by Urban Learners in partnership with Acland Burghley School with the support of the Heritage Fund. Acland Burghley School is a brutalist building designed by Howell, Killick, Partridge, and Amis (HKPA) between 1963-67. It is the home of MoBA and also hosts community, arts, and cultural events.

Join us / Membership

We are grateful for the wonderful support from all of our members, supporters and partners. If you would like to become a member or supporter of MoBA please contact us.

- ADD YOUR STORY

- ADD A BRUTALIST BUILDING

Already have an account? Sign In

Reset Password

Please enter your username or email address, you will receive a link to create a new password via email.

- Architecture

- Latest Issue

- Digital Issue

The concrete collective: A guide to Brutalism in London

The post-war architectural style, characterised by block-like forms usually cast in raw concrete or brick, defined an era of architecture in Britain

Intended to provide solutions to the city’s housing problem, the Brutalist movement was strongly guided by socialist ideology. Its buildings focus on communal areas, and seek to provide equal units of space to its users. Many of Brutalism’s leading architects, including Erno Goldfinger and Alison and Peter Smithson, believed they were creating revolutionary urban utopias.

The success or failure of these buildings in achieving their socialist goals is heavily debated. For a period of time Brutalism was favoured for institutional buildings, but by the 1980s they were spurned as too abstract and inhuman, and many were torn down. Here are 10 of the most recognisable amongst the concrete behemoths that survived demolition in London.

Southbank Centre and the National Theatre, 1976, Denys Lasdun

The Southbank Centre has been controversial since it opened, much loved and much maligned. Likened to a ‘nuclear power station’ by Prince Charles, it is a vast concrete structure with tiered volumes that step down towards the Thames. The neighbouring National Theatre, with its monumental inner volumes, houses three theatre stages, as well as interior communal spaces that Lasdun described as his ‘fourth theatre.’ It is surrounded by several generous public terraces.

Brunel University Lecture Centre, 1965-66, John Heywood

Built in the mid-60s, the Brunel University Centre was featured in the film A Clockwork Orange as a the dystopian Ludivico Medical Facility. Apart from this memorable appearance in cinema, the centre’s protruding concrete forms make it a Brutalist classic. It forms an expressive centre piece for the university’s campus.

Brunswick Centre, 1967-72, Patrick Hodgkinson

The grade II-listed Brunswick Centre was the only finished portion of Patrick Hodgkinson’s vision for Bloomsbury. It is a vast megastructure – a concrete realm of houses that are situated above a cinema and shopping walkway. Three decades after its completion, its raw concrete facades were covered with paint as per its designer’s original plans. Its mammoth flying buttresses are toned down by this recent colour scheme, which has lightened the development.

Royal College of Physicians, 1959-64, Denys Lasdun

A more delicate example of a Brutalist structure, Lasdun designed the Royal College of Physicians with a less intrusive geometric block plan. It is considered a Modernist masterpiece. Lasdun attempted to combine his progressive theories with the traditional character of the institution, celebrating the combination of old and new with dramatic interiors and a white mosaic exterior.

The organisation’s headquarters houses an ancient library with original 17th century oak panels from the College’s previous location, a marble portrait gallery and a concrete and glass ceremonial hall. The entrance cantilevers out dramatically, and the exterior is a masterful combination of curves and lines. The building is grade I listed.

Centre Point, 1963-66, Richard Seifert & Partners

Embodying Brutalism’s post-war optimism, Centre Point was thought to be beacon of a recovering city. Situated at the Tottenham Court end of Oxford Street, the 33-storey tower has a recognisable geometric concrete facade, with subtle v-shaped window mullions. It was one of the earliest skyscrapers in London and is still a commanding site in the city’s skyline.

The tower stood partially empty for the first decade after completion, and was highly criticised by housing activists, who saw its empty office floors as an insult to the many homeless people in London. In 2010 Conran and Partners was commissioned to update the building and convert office spaces to residential units; nearly 100 apartments were modernised and a series of communal amenities were added, such as a pool and a private clubhouse with treatment rooms.

The Barbican, 1965-76, Chamberlain, Powell and Bon

The Barbican is London’s best-known Brutalist megastructure. The 35-acre ‘city within a city’ hosts over 2000 apartments that weave around a series of inner gardens, as well as a vast arts centre and two schools. Designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon in the late 1950s, the estate was only officially opened in 1982.

The Barbican is an exemplary concrete structure with hand-picked textured facades. The attention to detail in the cultural and residential programming and the creation of oasis-like gardens has ensured the Barbican’s enduring success.

Trellick Tower, 1966-73, Erno Goldfinger

Trellick Tower is the quintessential London Brutalist building. Its austere facade has become iconic and the once-poorly maintained block is now a highly desirable address. The Grade-II listed housing tower in Notting Hill contains 217 flats across 31 floors. The main block structure is a thin slab, allowing all of its apartments to have views on either side of the building over the city.

The design for Trellick Tower was an evolution of Goldfinger’s earlier project Balfron Tower, which he designed for the poorer residents of Poplar in the East End. Trellick and Balfron share distinctive separate service towers, which provide access to the residential units and house the utilities.

Hayward Gallery, 1960-68, Denys Lasdun

Lasdun laid down the aesthetic foundations for the South Bank when he completed the Hayward Gallery and Queen Elizabeth Hall almost a decade ahead of his National Theatre. It is concrete at its most diverse – a patchwork of textures and geometric forms that rise up from the river Thames. The Hayward Gallery contains five exhibition spaces and three outdoor sculpture courts. Terraces and ramps link the galleries, the uppermost of which is lit by natural light that is allowed to enter through controlled roof windows.

Alexandra Road Estate, 1968-78, Neave Brown

Social housing at its most community-centric, the Alexandra Road Estate sits along the railway line in Camden. Its architect Neave Brown was working for the architecture department of Camden Council when he was commissioned to design the estate. Construction went severely over budget and took much longer than anticipated, but has since become highly acclaimed.

Featuring 520 apartments, a school, community centre, youth club and parkland, the high density, low-rise development is mounted onto rubber to minimise the noise from the passing trains, and the almost window-less facade facing the tracks also acts as an effective noise barrier. Its stark concrete volumes are complimented by the vast landscaping. It has been used in a number of dystopian films and television series.

Robin Hood Gardens, 1968-1972, Alison and Peter Smithson

The Robin Hood Gardens council estate was the culmination of the Brutalist architect duo Alison and Peter Smithson’s theories on socialist architecture. The housing estate in Poplar, not far from the Balfron, was constructed from pre-cast panels of concrete, with concrete balconies that were intended to serve as communal ‘streets in the sky.’ Poorly maintained, it almost immediately became synonymous with crime and vandalism. It was denied listed status in 2015 and is currently being demolished to make way for a new, even denser housing development.

From the Archive: A short history of the iconic Egg Chair by Arne Jacobsen

Henry Holland Studio’s Big Brekkie collection brings a playful touch to morning mealtimes

Christofle partners with Roland Garros in an exclusive collaboration

Editor's choice.

Design Destination: ICON’s tips for where to go and what to see in London Fields

Atelier L’Abri completes silver-clad house in forested hills of Canadian Laurentians

USM and Symbol Audio unveil new capsule collection of audio and record storage pieces

Photographer Ruben Hughes shares how he captures the streets of New York and Copenhagen

Shalini Misra’s new rug collection references the architectural beauty of India’s ancient stepwells

Architecture Icon: The Paimio Sanatorium and its humanistic approach to modernism

House Dokka combines simple geometry and natural materials to create a home that resembles a floating treehouse

Makhno Studio’s Gnizdo houses seamlessly blend tradition and futurism

This new eco-conscious hotel concept in the Trosa archipelago draws a discerning crowd

Clément Cividino’s restoration of a 1960s fibreglass pod by Nikolaos Xasteros lands in the Spanish countryside

Architecture Icon: The post-war designs of Yrjö and Irmeli Kukkapuro live on in their unique home studio

Architecture Icon: How the Noguchi Musuem advances the appreciation of its founder’s art and legacy

Fermob introduces new colours for 2024!

- Advertisement Feature

Hotels by Bisley

Privacy overview.

Brutalist Architecture in London: A Guide to the City’s Iconic Buildings

London’s brutalist architecture is a polarizing topic that divides opinions. The post-war architectural style, characterized by its clean lines and severe structures, is either loved or hated. However, for those who appreciate the style, London is a treasure trove of Brutalist architecture.

Some of the city’s most iconic buildings , such as The National Theatre, The Barbican, and The South Bank Centre, are excellent examples of Brutalist architecture. But there are also lesser-known gems waiting to be discovered, like The NLA Tower and Trellick Tower . In this article, we will explore some of the best Brutalist architecture in London and provide practical tips and a map to help visitors discover the city’s Brutalist treasures.

- 0.1 Key Takeaways

- 1 What is Brutalism?

- 2.1 The Barbican

- 2.2 Trellick Tower

- 2.3 Royal Festival Hall

- 2.4 National Theatre

- 2.5 Alexandra Road Estate

- 2.6 Brunswick Centre

- 2.7 Royal College of Physicians

- 2.8 The Standard

- 2.9 Centre Point

- 2.10 Brixton Recreation Centre

- 2.11 78 South Hill Park

- 2.12 One Kemble Street

- 3 Brutalist London Practical Tips and Map

Key Takeaways

- London is home to some of the world’s best Brutalist architecture.

- The National Theatre, The Barbican, and The South Bank Centre are some of the most iconic Brutalist buildings in London.

- Practical tips and a map are available to help visitors discover the city’s Brutalist treasures.

What is Brutalism?

Brutalism is an architectural style that emerged in the post-war era in the 1950s and gained popularity until the 1970s. It is characterized by the use of poured concrete or brick to create monolithic, blocky and severe styles and geometric structures.

One of the defining features of Brutalist architecture is its emphasis on showcasing the materials used in building construction, as well as the functional components of its structures. This means that elements such as lift shafts, ventilation ducts, staircases, and boiler rooms are integrated into the building’s fabric in ways that celebrate them as distinct features rather than hidden away.

In London, Brutalism was widely used in the reconstruction of the city after World War II, particularly for social housing and government buildings. However, its popularity led to its use extending beyond these spheres.

Best Brutalist Architecture in London

London is home to some of the most striking examples of Brutalist architecture in the world. These buildings, with their raw concrete facades and geometric forms, have become an integral part of the city’s landscape. Here are some of the best examples of Brutalist architecture in London.

The Barbican

The Barbican Centre is one of the most iconic examples of Brutalist architecture in London. Designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, the building was constructed in the 1980s to help regenerate the Cripplegate area of the City of London. The complex includes a mix of residential and commercial spaces, as well as the largest multi-arts and conference venue in Europe. Visitors can explore the labyrinth of pedestrian walkways and discover the hidden gem of a conservatory.

Trellick Tower

Trellick Tower, designed by Ernö Goldfinger, is a 31-storey tower that looms over Ladbroke Grove. Completed in 1972, the tower is one of London’s most recognizable Brutalist buildings. The tower’s unique design combines a main block of social housing with a service tower, connected via covered walkways every three floors. The cantilevered boiler house atop the service tower is the only curved element of the building.

Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is the largest venue in the Southbank Centre. Designed by Robert Matthew with Leslie Martin and Peter Munro, the building was constructed in the 1950s to represent the optimism and forward-thinking attitude of postwar Britain. The building’s avant-garde structure was meant to reflect the programme of events happening inside, creating a synergy between form and function. The interior features “classless-designed” bars and restaurants, as well as an open foyer policy that allows public access during opening hours.

National Theatre

Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre is a grand example of public sector Brutalist architecture. Built to make theatre accessible to the masses, the structure features a large Olivier Theatre that seats 1,160 people, alongside two smaller theatres that also seat significant numbers. The building’s complex layering of concrete reveals itself in stages, adding to the grandeur of the structure.

Alexandra Road Estate

The Alexandra Road Estate, designed by American architect Neave Brown, is a swooping swish of striking architecture and intricate design that reflects Brutalism’s utopian vision. The estate winds alongside Camden’s railway line and is a listed building. Brown also designed the Dunboyne Road Estate and Winscome Street Row Houses in Camden.

Brunswick Centre

The Brunswick Centre is a multi-purpose residential building and shopping centre in Bloomsbury. Designed by Patrick Hodgkinson, the building’s cream and sky blue colour scheme provides a different take on Brutalism. The centre was supposed to be part of a larger development razing its way through Bloomsbury, but in the end, only The Brunswick section was built. The light-filled walkways and symmetrical designs are some of London’s best.

Royal College of Physicians

Denys Lasdun’s design for the Royal College of Physicians is a modernist masterpiece that overlooks leafy Regent’s Park. The Grade I listed building manages to be sympathetic to the area’s palatial Regency architecture while also standing out as a Brutalist gem.

The Standard

The Standard is a Brutalist building that is softer and curvier than other buildings in this guide. It was the former Camden Town Hall Annexe and is now a swish hotel. The building’s pale Brutalist concrete frame is thrown into relief by the Gothic buildings of St Pancras looming in the background.

Centre Point

Centre Point, designed by Richard Seifart, was unveiled in 1966 and was one of the tallest buildings in London. The building was famously underutilized and was transformed into a block of luxury apartments in recent years.

Brixton Recreation Centre

Brixton Recreation Centre is a Grade II listed building that was nearly a failed project due to labour disputes and political struggles in Lambeth council during the late 70s and early 80s. The project was almost abandoned several times, but the recreation centre was completed in 1985. The building is another slice of Brutalist architecture that is now a much-loved community space.

78 South Hill Park

78 South Hill Park is a Brutalist building in Hampstead designed by Brian Housden. The building has an interesting origin story, as Housden redrew his plans to be more avant-garde after visiting influential Dutch designer Gerrit Rietveld. The result is a striking example of Brutalist architecture in Hampstead.

One Kemble Street

One Kemble Street is a cylindrical structure that was once home to the Civil Aviation Authority. The building is a fine example of the brash, brutalist architecture of the 60s, with little

Brutalist London Practical Tips and Map

For those interested in exploring London’s brutalist architecture, there are a couple of walking tours available such as the “London: Brutalist Architecture & History Walking Tour” and “Brutalism for Beginners.” It is worth noting that most of these buildings are open to the public, so visitors should take the time to explore the interiors as well as the exteriors. In some cases, visitors can even enjoy performances, dinner, or drinks in the buildings themselves, such as the Royal Festival Hall and the National Theatre. As the distances between the buildings can be considerable, it is recommended to wear comfortable shoes when walking from place to place.

The finest brutalist architecture in London and beyond

For some of the world's finest brutalist architecture in London and beyond, scroll below. Can’t get enough of brutalism? Neither can we.

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

Brutalist architecture in London

Brutalist architecture globally.

Can’t get enough of brutalist architecture? Neither can we. In London, neglected brutalist behemoths are being rebooted and given new life. The wave of savvy renovations is being led by a flock of eagle-eyed developers who wish to save – and capitalise on – these concrete urban structures' dramatic shapes. This is not just a London-focused trend as more brutalist architecture around the world is being given a new lease of life. In London alone we counted contemporary renovations of Centre Point and the Economist Building as part of the movement.

Read this report of new developments at London’s Balfron Tower or visit Brussels where a brutal behemoth is being converted into a co-working space , while in the States a Marcel Breuer buidling in Connecticut is being reimagined as a hotel. Or scroll below, for some of the world's finest brutalist architecture in London and beyond.

Centre Point, 1963-1966, by Richard Seifert & Partners

When completed in 1966, Centre Point represented a beacon of optimism within its original context of a run-down, post-war London, standing out for its avant-garde architecture and engineering. However, it remained underused for years until, in 2010, it was acquired by developer Almacantar, which enlisted Conran and Partners to bring the building into the 21st century. Now the design includes modern apartments, a lavish penthouse and a series of amenity spaces , including a pool and a private lounge/club house area with screening rooms and treatment rooms for residents and their guests.

Thamesmead, 1968

Housing at Thamesmead, Greenwich, London: view across the estate from an access deck, 1970s. © the artist / RIBA Collections

‘ Thamesmead ’. Semantically, the word sounds like a riverside Shakespearean ale house. But, in the public imagination, it conjures images of a 1970s, crime-ridden neighbourhood, and the droogish backdrop to Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 dystopian drama Clockwork Orange. Initially hailed as a futuristic ‘town for the 21st century’, construction of the London City Council-commissioned Thamesmead began in 1968. Despite early promise, it quickly gained a reputation for no-go areas and poor transport links. Recently, after a complicated history, punctuated by well-documented attempts to renew and rethink the area, Thamesmead has been undergoing an extensive regeneration project by Britain’s oldest housing association Peabody, which promises around 20,000 new homes, and improved community facilities. Additional writing: Elly Parsons

123 Victoria Street, 1970s, by Elsom, Pack & Roberts

Using Kvadrat curtaining, furniture from brands such as Vitra, Hem, Muuto and a specially-designed staircase, SODA Studio has conjured up classy offices in a brutalist block. The 40,000 sq ft workspace in London’s Victoria goes by the name of MYO, and is property firm Landsec’s first foray into flexible office space. SODA – the architects behind Soho’s new Boulevard Theatre – has converted the second and third floors of 123 Victoria Street , a 1970s building by Elsom, Pack & Roberts, which was refurbished eight years ago by Aukett Fitzroy Robinson. Inside, SODA took its cue from the blocky glazed exterior. ‘We didn’t want to fight against the building,’ says director Russell Potter. ‘Our driving principle was to create a rigorous grid with walls and partitions,’ which, he adds, they treated as ‘a kit of parts.’ These partitions add to the workspace’s flexible credentials. Additional writing: Clare Dowdy

Brixton Recreation Centre, 1974-1985, by George Finch

The now listed Brixton Recreation Centre, designed by architect George Finch and completed in the mid 1980s is one of the new additions of remarkable brutalist architecture included in the refreshed Brutalist London Map (Second Edition) by Henrietta Billings and with photography by Simon Phipps, published by Blue Crow Media. The map aims to highlight London's rich legacy in brutalist architecture in order to celebrate and help save many buildings from demolition. 'In 2022, seven years on from the first edition of the map, the environmental impact of demolishing these buildings and their vast stores of embodied carbon is alarmingly clear. From a sustainability, as well as a heritage perspective, we cannot afford to lose any more of them,' says the author. More buildings that made their way into the map for the first time are the National Archives at Kew; Blackheath Meeting House; the Royal College of Art’s Darwin Building; and the Camden Town Hall Annexe, recently converted into the Standard Hotel.

Economist Building, 1959-1964, by Alison and Peter Smithson

‘You’d originally sit with a typewriter on the windowsill, then swing round and write longhand at your desk,’ says Deborah Saunt, explaining the Smithsons’ tailor-made office space in the Economist Building for The Economist magazine. Saunt’s practice, DSDHA, won the competition to refurbish this London icon, a building that took the raw pragmatism of brutalism in another, very different direction. The best-known shots of the structure – three ‘roach bed’ Portland stone-clad towers around a central plaza – were taken by a young Michael Carapetian, a friend of the Smithsons who brought a cinematic, reportage-like quality to his images. The AA-trained architect recalls that he ‘wanted a day that was slightly misty and wet. It was the first time a new building had been photographed in the rain.’ The imagery cast has a moody, atmospheric light. ‘It wasn’t seen as shocking, but the building was respected for its ability to blend in with the rest of the street,’ he recalls. ‘The idea was to elevate the plaza above the rest of the street – a sort of utopian idea.’ Saunt says the practice envisaged the structure as a blueprint for a new form of urbanism, linked by walkways and quasi-public spaces. Her studio’s modest but comprehensive refurbishment strips away interiors that themselves were wholesale replacements of Smithsons’ careful original detailing. ‘We’ve made it a lot more harmonious, but have embraced their vision of architecture as a framework,’ she says. The revitalised building will see one of London’s most elegant public spaces brought back to life.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

National Theatre, 1976, by Denys Lasdun

The National Theatre courted controversy from the outset, with the UK's favourite architectural scourge, Prince Charles, casually dismissing the capital's new cultural flagship as a ‘nuclear power station’. Sir Denys Lasdun's rigorously composed concrete statement still looks at fresh as ever, thanks to an £80m refurb by Haworth Tompkins in 2015, not to mention the quality of the original design. With generous terraces that step down to the Thames and a monumental assemblage of interior volumes, spaces and stages, it remains one of London's contemporary classics. The city is also home to Lasdun's other masterpiece, the 1964 Royal College of Physicians, a Brutalist stage set of concrete and stone, rising up amongst the genteel stucco terraces of Regents Park. Lasdun's Theatre refined the aesthetic that had already been established by the adjacent Hayward Gallery and the Queen Elizabeth Hall. These buildings still represent a substantial chunk of London's cultural infrastructure and were built between 1960 and 1968 on the site of the Festival of Britain, alongside the remodelled Royal Festival Hall. Designed by a team of architects employed by the Greater London Council – including key members of the iconoclastic Archigram studio – this group of buildings represents concrete at its most diverse and distracting, a collage of textures and forms that rises up beside the river in a thrilling urban jumble. Much loved, forever threatened, but an integral part of the London experience

Alexandra Road Estate, 1968-1978, by Neave Brown

Social housing at its most optimistic, aesthetically sophisticated and single-minded best, the Alexandra Road Estate snakes alongside a railway line in Camden, containing over 500 homes in a variety of configurations. Created by the late Neave Brown – then working in Camden Council's Architecture Department – it went wildly over-budget and later found infamy as a location for dystopian films and television. Yet despite the controversy it continues to be a desirable place to live, with its shuttered concrete flanks rising steeply above a pedestrianised central street.

One Kemble Street, 1968, by George Marsh

This cylinder and box office block is a typical piece of Sixties grandstanding, almost entirely blasé about its immediate surroundings. These days it finds itself an integral part of the eclectic cityscape. Designed by George Marsh, one of the partners in Colonel Richard Seifert's massive commercial architecture outfit, the circular building showcased Seifert's trademark angular modular façade and muscular supporting columns. It was also the HQ to the UK's Civil Aviation Authority for many years. Currently, the central London structure - also known as Space House - is being given a new lease of life by developers Seaforth Land and architects Squire and Partners, who are on site with a transformation of the iconic shell into modern office and retail spaces.

Brunswick Centre, 1972, by Patrick Hodgkinson

Patrick Hodgkinson's original vision for Bloomsbury consisted of a vast trench of concrete dwellings and lecture halls, stomping across the remnants of Georgian London with Brutalist glee. The only chunk to be finished, the Brunswick Centre, is perhaps London's sole megastructure, a concrete valley of houses arranged above a shopping parade and cinema. It took three decades before a programme of refurbishment and upgrade works covered the raw concrete in the paint Hodgkinson originally specified. Now a highly desirable and light-filled place to live, it offers an insight into the grandiose schemes of decades past.

The Barbican Estate, 1965-1976, by Chamberlain, Powell and Bon

For many Londoners the Barbican defines contemporary Brutalism. Yet behind the fortress-like construction of this 35-acre city centre site is a veritable oasis of greenery, culture, water and calm, all wrapped up in some of the most abrasive concrete finishes ever seen. The Barbican almost took as long to build as a city, with initial plans drawn up in the 50s and the final concrete slotted into place in the arts centre, which opened in 1982. The firm of Chamberlain, Powell and Bon oversaw this expansive piece of urbanism, which continues to define the highest standards of concrete design.

Keeling House, 1957, by Denys Lasdun

An earlier outing by Denys Lasdun, Keeling House in East London was intended to form a 'street in the sky', replacing the low-rise back-to-back houses that had succumbed to war damage and old age. The cluster block form was carefully designed, with interlocking, overlooking apartments somehow combining both community and privacy, but it was rather less meticulously built. By the early 90s the block had fallen into disrepair; a pioneering refurbishment by Munkenbeck and Marshall gave it a new lease of life, adding penthouses on top and even securing Lasdun's blessing in the process.

Trellick Tower, 1966-1972, by Ernö Goldfinger

The Trellick Tower is the archetypal symbol of brutalism in West London, a bold cliff of shuttered concrete that overlooks the city's western reaches. Despite a rocky start, the Trellick subsequently ascended to the status of cultural icon, adorning everything from t-shirts to coffee cups. Ernö Goldfinger's generous design initially suffered from poor maintenance but today the building's generous apartments are highly sought after, combining space, light and views, with services pushed to one side and contained in a slim adjoining tower.

78 South Hill Park by Brian Housden

Hampstead Heath’s 78 South Hill Park doesn’t look like a house born of embarrassment, but that is exactly what it is. In the 1950s, architect Brian Housden visited Dutch De Stijl master Gerrit Rietveld (who played roughly the role in architecture that Mondrian played in painting) and, when they parted, Rietveld told Housden he’d love to see the plans of the Hampstead house he was working on. Housden said he was mortified, ashamed of the timid designs he had drawn and decided to start over. Rietveld never saw the drawings, but the result is extraordinary – a brutalist house on the edge of Hampstead Heath that is one of London’s most surprising and inventive post-war dwellings. The 1924 Rietveld Schröder House, which so inspired Housden, is always photographed as a freestanding, almost autonomous building, but, in fact, bookends a dull brick Utrecht terrace. Similarly, Housden’s house squats between a pair of more conventional modernist blocks (including one by Howell, Killick, Partridge & Amis, architects of London’s Young Vic theatre), its muscular concrete frame seeming to push them apart, to defy them to crush it. Additional writing: Edwin Heathcote

Barbican sunken bars by Kam Bava

The much loved Barbican Estate in London comprises many parts and elements – from its famed performing arts centre, a key cultural hub in the City of London and beyond and the largest of its kind in Europe, to its iconic residences, outdoor spaces and brutalist architecture environment. Its scale means that there are many smaller areas, however, which often remain lesser-known, yet are no less important to the Barbican experience. Part of the Grade II-listed Barbican Centre Theatre, the Barbican sunken bars are two hospitality corners of the seminal modernist development, constructed between 1965 and 1971 and located under the steps of the theatre. The spaces were in need of a refresh, so London architect Kam Bava was asked to lead a careful restoration and interior redesign to breathe new life to the complex's much-loved leisure offering.

The bars’ facelift was not just about aesthetic fixes and a superficial polish. The architect ensured a technical upgrade was incorporated as well, because, after years of intensive use, the listed fabric was in dire need of an update. Seeking to maintain the interior's original character, as well as emphasise reuse and recycling as an approach, Bava cleverly redeployed elements found within the Barbican campus. ‘The steel bar structure is made from the handrails on the [Barbican] centre, and the ceiling comes from the art gallery. The handling of these pieces together with the use of mirrors creates a very different scale of experience, using very familiar design cues,' he explains. Read more

South London house by Whittaker Parsons

This brutalist treasure in south London squeezes a surprising amount of space onto an unpromising spot, enhancing the streetscape. The addition, next to a terraced house, features a tough, hard-wearing exterior that brings a little brutalist architecture glamour to its neighbourhood. Whittaker Parsons’ Corner Fold House was designed for a downsizing couple, who swapped a conventional Victorian terrace for a faceted modern house that makes the most of its awkward site, tucked in between an immovable electricity sub-station and the clients’ former family home. The process was remarkably smooth, according to the clients, who were able to transform a garden plot at the side of their house into a completely separate dwelling, digging down to create a new basement and even finding enough space for a small rear terrace. Describing it as ‘the experience of a lifetime’, the clients are especially impressed by Whittaker Parsons’ ability to maximise the amount of available space.

Habitat 67, Montreal, by Moshe Safdie

As Portland’s cement industry bloomed at the turn of the 1900s and architects became increasingly tired of conventional materials, Montreal became something of a playground for concrete experimentation. From Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67 – the instantly recognisable model community on the Marc-Drouin Quay – to Roger Taillibert’s monolithic Olympic Stadium, constructs of all shapes and sizes are brought into the fold.

CBR HQ, Brussels, Belgium by Constantin Brodzki

Constantin Brodzki is less than enthusiastic, to say the least, whenever he hears of one of his buildings being renovated. At 93 years old, the Belgian architect is still very much engaged with the architecture world, and he’s eager to point out the ways in which he would like his modernist legacy to be preserved. ‘I have experienced catastrophes before, so I’m suspicious,’ Brodzki admits, taking out plans and photos to show how some firms have botched his former projects. One of his designs, the former HQ of the cement company CBR in Brussels, is currently being converted into a new outpost for Antwerp co-working concept Fosbury & Sons. Close to the Sonian Forest, it’s just ten minutes from the high-end Avenue Louise. For Fosbury & Sons’ founders Stijn Geeraets and Maarten Van Gool, the initial impetus to take on the modernist office building, with its characteristic façade of curved concrete modules, was all about the immediate visual impact. But as they started to explore the building, the full package captivated them. Additional writing: Siska Lyseens

Zvonarka Central in Brno, Czech Republic

Brno’s Zvonarka Central Bus Terminal has been a key Brutalist architecture landmark in the city since it first opened in 1988 - and is among the country’s most notable remaining examples of the genre. But years of intense use and high maintenance costs had resulted in a tired, decaying building in dire need of a refresh. Now, the Brutalist bus terminal has been given a new lease of life courtesy of architects CHYBIK + KRISTOF, who in 2011 embarked on a self-initiated journey to restore the famous building to its former glory. The design team worked with the station’s private owners and raised awareness through social media to instigate a discussion about the station’s future, securing the necessary funding for the redesign works in 2015. ‘Demolitions are a global issue,’ explains co-founding architect Michal Kristof. ‘Our role as architects is to engage in these conversations and demonstrate that we no longer operate from a blank page. We need to consider and also work from existing architecture – and gradually shift the conversation from creation to transformation. Read more

Van Wassenhove House, Belgium by Juliaan Lampens