Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

What Are the Health Benefits of Active Travel? A Systematic Review of Trials and Cohort Studies

Affiliation Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation General and Adolescent Paediatrics Unit, UCL Institute of Child Health, London, United Kingdom

- Lucinda E. Saunders,

- Judith M. Green,

- Mark P. Petticrew,

- Rebecca Steinbach,

- Helen Roberts

- Published: August 15, 2013

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912

- Reader Comments

Increasing active travel (primarily walking and cycling) has been widely advocated for reducing obesity levels and achieving other population health benefits. However, the strength of evidence underpinning this strategy is unclear. This study aimed to assess the evidence that active travel has significant health benefits.

The study design was a systematic review of (i) non-randomised and randomised controlled trials, and (ii) prospective observational studies examining either (a) the effects of interventions to promote active travel or (b) the association between active travel and health outcomes. Reports of studies were identified by searching 11 electronic databases, websites, reference lists and papers identified by experts in the field. Prospective observational and intervention studies measuring any health outcome of active travel in the general population were included. Studies of patient groups were excluded.

Twenty-four studies from 12 countries were included, of which six were studies conducted with children. Five studies evaluated active travel interventions. Nineteen were prospective cohort studies which did not evaluate the impact of a specific intervention. No studies were identified with obesity as an outcome in adults; one of five prospective cohort studies in children found an association between obesity and active travel. Small positive effects on other health outcomes were found in five intervention studies, but these were all at risk of selection bias. Modest benefits for other health outcomes were identified in five prospective studies. There is suggestive evidence that active travel may have a positive effect on diabetes prevention, which may be an important area for future research.

Conclusions

Active travel may have positive effects on health outcomes, but there is little robust evidence to date of the effectiveness of active transport interventions for reducing obesity. Future evaluations of such interventions should include an assessment of their impacts on obesity and other health outcomes.

Citation: Saunders LE, Green JM, Petticrew MP, Steinbach R, Roberts H (2013) What Are the Health Benefits of Active Travel? A Systematic Review of Trials and Cohort Studies. PLoS ONE 8(8): e69912. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912

Editor: Jonatan R. Ruiz, University of Granada, Spain

Received: January 31, 2013; Accepted: June 13, 2013; Published: August 15, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 Saunders et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research programme (project number 09/3001/13). The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health. The funders had no role in the design, conduct or reporting of project findings.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

The link between physical activity and health has long been known, with the scientific link established in Jerry Morris' seminal study of London bus drivers in the 1950s [1] . There is also good ecological evidence that obesity rates are increasing in countries and settings in which ‘active travel’ (primarily walking and cycling for the purpose of functional rather than leisure travel) is declining [2] , [3] . Given that transport is normally a necessity of everyday life, whereas leisure exercise such as going to a gym may be an additional burden, and is difficult to sustain long term, [4] , [5] encouraging ‘active travel’ may be a feasible approach to increasing levels of physical activity [6] . It is therefore plausible to assume that interventions aimed at increasing the amount of active travel within a population may have a positive impact on health. This has been the underlying rationale for recent public health interest in transport interventions aiming to address the obesity epidemic and a range of other health and social problems [7] ; for example, “For most people, the easiest and most acceptable forms of physical activity are those that can be incorporated into everyday life. Examples include walking or cycling instead of travelling by car, bus or train” [8] . Active travel is seen by policy makers and practitioners as not only an important part of the solution to obesity, but also for achieving a range of other health and social goals, including reducing traffic congestion and carbon emissions [9] .

It has been recommended that the public health community should advocate effective policies that reduce car use and increase active travel [10] . One recent overview concluded that active travel policies have the potential to generate large population health benefits through increasing population physical activity levels, and smaller health benefits through reductions in exposures to air pollution in the general population [6] . However, while a systematic review [11] has found that non-vigorous physical activity reduces all-cause mortality, the two studies which looked at active commuting alone [12] , [13] found no evidence of a positive effect. There are a number of reasons why active travel may not contribute to overall physical activity levels. Some studies of young children have found no differences in overall physical activity levels for active and non-active commuters [14] , [15] , [16] , perhaps because the distance walked to school may simply be too short to make a significant contribution. For both children and adults, it is unclear how far individuals may offset the extra effort of cycling or walking with additional food intake, or by reducing physical activity in other areas of everyday life. Additionally, there is evidence that the health benefits of exercise are not shared equally across populations, with the cultural and psychological meanings of activities such as walking or cycling potentially influencing their physiological effects [17] , [18] .

A reliable overview of the strength of the scientific evidence is therefore needed because the causal pathways between active travel and health outcomes such as obesity are likely to be complex, and promoting active travel may have unintended adverse consequences [19] , for example by reducing leisure activity.

Existing studies show a mixed picture on the relationship between active travel and health outcomes including obesity [20] . Recent systematic reviews have focussed almost exclusively on cross-sectional studies [20] , [22] , [23] , or one narrow health outcome [24] or on combined leisure and transport activity [25] . Obesity is a particular focus because the rise in the prevalence of obesity over the past 30–40 years has occurred in tandem with the decline of active travel, and overweight and obesity are now the fifth leading risk for death globally as well as being responsible for significant proportions of the disease burden of diabetes (44%), ischaemic heart disease (23%) and some cancers (7–41%) [21] .

Given the widespread promotion of active travel for reducing obesity in particular, and improving the public health in general, it is perhaps surprising that is, to date, no clear evidence on its effectiveness. To address this gap, a systematic review of evidence from empirical studies was carried out with the objective of assessing the health effects of active travel specifically (rather than of physical activity in general, where the evidence is already well-established). This review was undertaken to identify and synthesise the relevant empirical evidence from intervention studies and cohort studies in which health outcomes of active travel have been purposively or opportunistically measured to assess the impact of active travel on obesity and other health outcomes.

Eleven databases were searched for prospective and intervention studies of any design (Cochrane Library, CINAHL Plus, Embase, Global Health, Google Scholar, IBSS, Medline, PsychInfo, Social Policy and Practice, TRIS/TRID, Web of science – full details in Table 1 ). The review protocol is available on request from the authors. The search strategy adapted the search terms developed by Hoskings et al. [26] (2010 Cochrane Review) and Bunn et al. [27] (2003) to create a master search strategy for Medline (see Appendix S3 ) which was then adapted as needed to fit each database (The exact search strategy used in each database is available from the corresponding author). No time, topic or language exclusions or limits were applied. Hand-searching of relevant studies was also conducted, and bibliographies of identified papers were checked along with those of papers already known to the researchers. The PRISMA flow chart, PRISMA checklist and search strategy are included in Appendices S1, S2, and S3 respectively.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.t001

Two reviewers independently identified potentially relevant prospective studies. If it was not clear from the title and abstract whether the article was relevant to active travel, then the paper was reviewed in detail. Non-English language studies were eligible for inclusion, though no relevant studies were identified. One reviewer then screened the articles using the following inclusion criteria:

- Prospective study examining relationship between active travel and health outcomes; or study evaluating the effect of an active travel intervention; and

- Active travel (walking or cycling for transport rather than work or leisure) measured in a healthy population (e.g. using self report measures, or use of pedometers); and

- Health outcome included.

Retrospective and single cross-sectional studies (e.g. one-off surveys) were excluded.

One reviewer extracted data including information on methods, outcomes (as adjusted relative risks, or hazard ratios; if these were not available or calculable, other effect measures were extracted – e.g. mean changes), populations and setting for each study. The quality assessment was conducted using a standardized evaluation framework, the ‘Evaluation of Public Health Practice Projects Quality Assessment Tool’ (EPHPP) al. [28] [29] . Two reviewers independently reviewed each study and discussed any differences to produce consensus scores for each study against each quality criterion (see Table 4 ).

Twenty-four studies reported in thirty-one papers were included (see Tables 2 and 3 ). Five were prospective cohort studies with obesity-related outcomes, all in children; fifteen were prospective cohort studies with other health outcomes; and five were intervention studies with other health outcomes (details of excluded studies available on request from the authors). For the prospective cohort studies the results are presented adjusted for covariates. There was variation in what adjustments were made by different studies but the adjustments did not have large impacts on effect size. Details of the methodological assessment of each paper are included in Table 4 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.t002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.t003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.t004

1. Studies in adults

Eighteen studies in adults were identified; five intervention studies and thirteen prospective cohort studies.

1.1 Intervention studies.

The intervention studies included adults in north-west Europe and measured multiple health outcomes including fitness, blood pressure, cholesterol, oxygen uptake, and body weight [30] , [31] , [32] , [33] , [34] , [35] , [36] ; none measured obesity directly. Three studies found improvements in fitness measures in the intervention group compared with the control group [30] , [33] , [35] , [36] , one found increased physical activity levels [31] , [32] , [37] but one did not [35] , [36] , two found no significant change in body weight [31] , [32] , [35] , [36] and one found significantly higher scores for 3 of the 8 domains of the SF-36 in the intervention group [34] . All these studies were at risk of selection bias and none reported baseline differences between intervention and control groups for potential confounders [30] , [31] , [32] , [33] , [34] , [35] , [36] , [37] . However, all five studies were rated moderately overall. All but one [30] were controlled with appropriate statistical analyses. All but one [34] had low levels of drop-out and ensured that the intervention was consistently applied.

1.2. Prospective Cohort Studies.

The 13 prospective cohort studies of adults (described below) [12] , [13] , [38] , [39] , [40] , [41] , [42] , [43] , [44] , [45] , [46] , [47] , [48] , [49] , [50] , [51] covered a range of health outcomes. Eight were conducted in Scandinavia [12] , [38] , [39] , [40] , [42] , [43] , [44] , [45] , [46] , [47] . This may reflect the longer history of higher population levels of active travel, as a result of which questions on active travel have been included in population surveys over recent decades. Overall, these studies reported conflicting findings when measuring similar mortality and cardiovascular outcomes, with the exception of diabetes where the 2 studies both found statistically significant positive results for active travellers compared with non-active travellers and hint at a dose-response relationship [43] [52] .

Five studies investigated all cause mortality. One study in Denmark [38] found a significantly lower all-cause risk of mortality in cycle-commuters compared with non-cyclists - this was not found in a second such study in Finland [12] . Batty et al. (2001) [13] also found no statistically significant differences for 12 mortality endpoints between men in London, UK who actively travelled more or less than 20 minutes on their journey to work. Matthews et al. (2007) [48] studied women in China and found no significant relationship between walking and cycling for transport and all cause mortality [48] . Besson et al (2008) [53] studied men and women in Norfolk, UK and found a non-significant reduced risk of all cause mortality in those who travelled actively (measured as more than 8 metabolic equivalent task values (MET.h.wk −1 )). None of these studies were rated consistently strong or moderate across all quality criteria. However they did all measure different levels of active travel among participants, which was a strength.

Five studies reported on cardiovascular outcomes. Besson et al.(2008) [53] found no significant reduction in cardiovascular mortality risk among active travellers whereas Barengo (2004) [12] in Finland found it to be significantly lower (adjusted hazard ratio 0.78 [CI: 0.62–0.97]) only among women actively travelling 15–29 minutes each way to work compared with those travelling less than 15 minutes each way but not in those travelling more than 30 minutes each way, and not in men. Hu et al (2005, 2007, 2007) [42] , [44] , [45] , also measured Coronary Heart Disease and found a significant relationship in women who travelled 30+ minutes per day (0.80 [CI:0.69–0.92]) compared with those who did not travel actively at all. Like Barengo (2004) [12] , they found no relationship between active travel and Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) in men. Barengo (2005) [39] found no difference in hypertension risk between those travelling more or less than 15 minutes each way to work. Hayashi et al. (1999) [41] found a statistically significant reduced risk of hypertension in those men in Osaka, Japan who walked 21 minutes or more to work compared with men who walked less than 10 minutes (adjusted relative risk 0.70 [CI: 0.59–0.95]). However, it was not clear from either of these papers how frequently the active travellers walked to work. Wagner et al. (2001, 2002, 2003) [49] , [50] , [51] found a statistically non-significant increase in risk of CHD events in men walking and cycling to work, although the amount of exercise taken while actively commuting was not recorded.

Four studies examined health outcomes other than all cause mortality or cardiovascular disease. Two studies found significant benefits of active travel for reducing diabetes risk. A study in Japan by Sato et al found a 27% reduced odds of type 2 diabetes among men who walked more than 21 minutes to work compared with those who walked less than 10 minutes (CI:0.58–0.92) [52] . A study in Finland [43] found the relative risk for Type 2 diabetes to be 34% lower among active travellers travelling 30 minutes or more per day compared with those not travelling actively (CI: 0.45–0.92). Luoto et al. 2000 [47] reported a non-significant reduction in relative breast cancer risk at 15 years follow-up of 0.87 (CI: 0.62–1.24) in women who actively travelled more than 30 minutes each day. Moayyeri et al. (2010) found no significant association between active travel and bone strength and fracture risk, but the numbers of study participants who travelled actively were extremely small [54] .

2. Studies in children

No intervention studies in children were identified. Four prospective cohort studies were identified with obesity outcomes and two with other health outcomes.

2.1 Obesity.

One prospective cohort study measured the BMI of children aged 13 and again two years later in the Netherlands and Norway [55] . This study found that those children who continued to cycle to school throughout the study period were less likely (OR 0.44, 95% confidence interval 0.21,0.88) to be overweight than those who did not cycle to school, those who took up cycling and those who stopped cycling to school. Also those who stopped cycling to school during the study were more likely to be overweight than the other groups combined (OR 3.19, 95% confidence interval 1.41, 7.24). However the authors acknowledged that there were some limitations to this study including uncontrolled confounding variables and a relatively high dropout of 56% of participants between baseline and follow-up measurements. A study in Denmark and Sweden with six year follow-up of children from aged nine found no significant association between the obesity measures (BMI, skin-folds and waist circumference) and travel mode [56] [29] . Three other prospective cohort studies with obesity outcomes were all conducted in North America and included children aged ten years or younger at baseline who were followed up for between six months and two years [57] , [58] , [59] . BMI measurements were taken in all three studies and skinfold measurements were taken in two of the studies. There was no significant association between active travel and the obesity outcome measures in any of the studies. All three studies were rated low on the quality assessment measure as no data on baseline differences between groups were presented.

2.2 Other health outcomes.

Two studies examined health outcomes other than obesity. One study conducted in Denmark and Sweden found that children who cycled to school in Denmark had significantly better cardio-respiratory fitness [40] and cardiovascular risk markers than those who did not [56] . This study took a range of measures of school children aged 9 and repeated the measurements after six years. In Sweden, children who cycled to school increased their fitness 13% more than those who used passive modes and 20% more than those who walked during the six year period. Children who took up cycling during the follow up period increased their fitness by 14% compared with those who did no t [29] . However, no significant association between travel mode to school and cardiovascular risk factors was found in the Swedish arm of the study. Interestingly, the Danish arm of the study found that walkers had the same fitness levels as those who travelled by ‘passive’ modes [56] . While the study scored moderately well for selection bias (76% participation in Denmark), drop out from this study was 60% in Sweden and 43% in Denmark. This study, as was the case for many of the prospective cohort studies, may have been at risk of contamination or co-intervention as monitoring during the follow-up period was not reported. Lofgren et al. (2010) [46] also studied children actively travelling to school in Malmö, Sweden and measured a range of bone health indicators but found no significant relationship. This study scored relatively well in the quality assessment, with good controlling of confounders and high participation levels, although as with all the prospective cohort studies scored weak on study design.

This is the first review to bring together all prospective observational and intervention studies to give an overview of the evidence on health effects of active travel in general. Previous systematic reviews of health outcomes of active travel have included primarily cross-sectional studies from which reliable inferences about causality cannot easily be drawn, or have relied on indirect evidence on the effects of physical activity on health, as opposed to the effects of active travel. Although we found no prospective studies of active travel with obesity as a primary outcome in adults, and no significant associations between obesity and active travel in studies which included children, for other health outcomes small positive health effects were found in groups who actively travelled longer distances including reductions in risk of all cause mortality [38] , hypertension [41] , and in particular Type 2 diabetes [43] , [52] .

One challenge to synthesising and using this evidence is that “active travel” is not defined consistently across studies, and the definition is dependent on what is considered normal in a particular setting. For example Luoto (2000) [47] , and Barengo (2004, 2005) [12] , [39] considered active travel to be more than 30 minutes per day and inactive travel to be less than 30 minutes per day. Batty (2001) [13] , Sato (2007) [52] and Hayashi (1999) [41] however considered active travel to be more than 20 minutes per day. Differences in health outcomes between people who actively travel 29 minutes per day and those who travel 31 minutes per day are unlikely, so differences between active and sedentary populations may be masked by the methods by which active travel is defined and reported. Meanwhile Besson (2008) [53] and Moayyeri (2010) [54] considered active travel to be more than 8 metabolic equivalent task (MET) hours per week while Matthews (2007) [48] considered it to be more than 3.5 metabolic equivalent task hours per day which may reflect differences in norms between UK and China in terms of active travel.

In light of this, users of the findings of this and similar reviews need to consider the extent to which we can generalise between studies conducted in different countries or settings. In particular, the amount of exertion required to travel actively may be greater in some settings than others for the same journey time, due to differences in congestion, terrain and climate. In countries where current levels of physical activity are low (such as the UK, where only 39% of men and 29% of women achieve 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity of any type five times a week [60] [61] ) adding 30 minutes of active travel per day might well produce much larger changes in health at a population level than were measured in non-UK studies. The prospective cohort studies also tended to focus on travel to work or school rather than active travel for general transportation, which again may limit generalisability.

The study by Cooper et al. (2008) [40] of school children in Odense, Denmark found that 65% of boys and girls walked or cycled to school, a much higher proportion than is currently found in the UK. However, journey times were less than 15 minutes for the majority of active travellers so the health effects of active travel for such short periods are difficult to measure in isolation. This highlights one of the difficulties of assuming active travel to school in young people to be a major source of physical activity, as it is common for children only to walk or cycle to school when the journey time is relatively short. In adults as little as 10 minutes of physical activity are acceptable to contribute to their weekly physical activity target of minimum 150 minutes. However children aged five – 18 are expected to be physically active for a minimum of 420 minutes per week [8] so a short active commute to school will not make a significant contribution to their overall physical activity requirements. The study by Lofgren et al. [46] included a study population with fairly high levels of physical activity overall and half the participants were active travellers, which makes it difficult to attribute health outcomes to active travel alone, as active travel may not contribute significantly to participants overall physical activity levels.

De Geus et al. (2007) [30] highlighted one of the difficulties of measuring active travel in intervention studies as they found that study participants cycled 13% faster when their fitness was being measured compared to their usual speed on their daily cycle commute. The process of measuring active travel can therefore result in an over-estimate of the health benefits conferred by active travel. It is also not clear whether levels of active travel impact on levels of other types of physical activity such as sport and leisure. This relationship has been explored by, among others, Dombois et al who found no relationship between levels of sports activity and mode of travel in adults in the Swiss Alps [62] , and also by Santos et al who found a more complex relationship between different types of activity in children in Portugal [63] . Thus issues including type of terrain, problems of definition, study design and the difficulty of disentangling the effects of active travel from more general physical activity make synthesis difficult.

There is a particular challenge in measuring health outcomes in children because some health outcomes relating to physical activity can take many years to develop. For example an intervention study by Sirard et al. involving children in the USA measured moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in a randomised controlled trial with 12 participants and a two week duration [37] . However, it could not be included in this review because it did not measure a health outcome.

This review also highlights the difficulty in measuring health outcomes of active travel in the general population. In prospective cohort studies if the follow-up period is short then it may not be possible to measure health effects that take many years to appear. Conversely in those studies which do have long follow-up periods of many years there is the risk that active travel has not been consistently adhered to throughout the follow up period.

The likelihood of health outcomes will depend on the context within which individuals are travelling – length of journey, frequency of travel, nature of the terrain, risk of injury, levels of air pollution and so on as well as other aspects of the lifestyles of the participants. For example travelling actively may mean that the individual is more or less likely to be physically active at other times, or they may modify their diet. It may mean that they are more or less likely to strengthen social networks. It is also important to note that active travel not only potentially benefits health by way of physical activity but may also off-set air pollution from motorised vehicles and contribute to social and environmental goals such as improving social cohesion and reducing CO 2 emissions. These combined benefits are a potent argument for promoting active travel, and emphasise the importance of models which incorporate both health and non-health benefits [64] , [65] such as carbon dioxide emissions.

Finally, designing searches which are both sensitive and specific is a challenge for public health systematic reviews. It is interesting to note that over 70% of the studies we identified were initially found through hand-searching, although some subsequently appeared in the database searches, which highlights the importance of a broad search not confined to electronic sources. While it is possible that studies may have been missed, our comprehensive search for studies makes it unlikely that a significant body of work has been excluded.

While the studies identified in this review do not enable us to draw strong conclusions about the health effects of active travel, this systematic review of intervention and prospective studies found consistent support for the positive effects on health of active travel over longer periods and perhaps distances, and it is of interest that there is some evidence that active travel may reduce risk of diabetes. This may be an important area for future research.

These cautious conclusions on the health impact of active travel do not, of course, mean that now is the time to confine active travel to the walk from the front door to the car door. The evidence on the effect of physical activity is sufficiently strong to suggest that the part played by active travel is well worth maintaining. Other aspects of active travel, including a reduction in pollution, and in carbon footprint are clear potential co-benefits and likely to become even more so.

Supporting Information

Appendix s1..

PRISMA flowchart.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.s001

Appendix S2.

PRISMA checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.s002

Appendix S3.

Search strategy.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069912.s003

Acknowledgments

We thank the other members of the project team (Phil Edwards, Paul Wilkinson, Alasdair Jones, Anna Goodman, John Nellthorpe and Charlotte Kelly) for their advice.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: LS JG MP RS HR. Performed the experiments: LS JG MP RS HR. Analyzed the data: LS JG MP RS HR. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: LS JG MP RS HR. Wrote the paper: LS JG MP RS HR.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 7. Wanless D, Treasury H (2004) Securing good health for the whole population: final report. London: HM Treasury. 1–222 p.

- 8. Department of Health (2011) Start active, stay active: A report on physical activity from the four home countries' Chief Medical Officers. Department of Health, Physical Activity, Health Improvement and Protection.

- 21. World Health Organization (2011) Obesity and overweight.

- 28. Effective Public Health Practice Project (2009) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies.

- 60. Health Survey for England (2009) Health Survey for England 2008. The Health and Social Care Information Centre.

Health benefits of active travel: preventable early deaths

19 April 2021

- Active travel

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Facebook

- Share on WhatsApp

- Share by email

- Link Copy link

- If walking and cycling rates in all regions in England increase to the same level as the regions with the highest average daily miles walked and cycled per person, around 1,190 early deaths could be prevented each year.

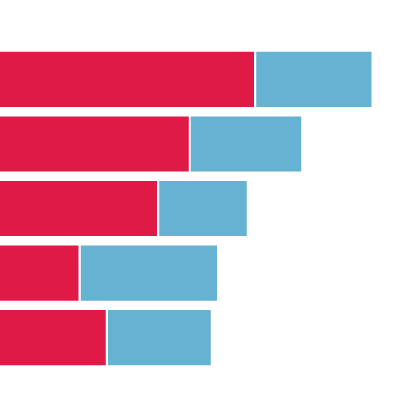

This chart shows the estimated number of preventable early deaths due to increased physical activity, if walking and cycling rates in all regions met the highest existing rates, for different age groups in each region of England. The estimates are derived from the World Health Organization’s health economic assessment tool (HEAT) , which calculates the reduction in mortality as a result of physical activity from regular walking and cycling.

Increasing physical activity and minimising the time spent sitting down helps to maintain a healthy weight and reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer and depression . The UK Chief Medical Officers recommend that adults should do at least 150 minutes of moderate activity, or 75 minutes of vigorous activity, each week.

The number of preventable early deaths is the difference between the current level of walking and cycling and a hypothetical scenario in which walking and cycling rates for different age groups in all regions increase to the same level as the regions where each age group has the highest average daily miles walked and cycled per person.

- In England, the average number of early deaths prevented is 1,189 per year, assuming that the hypothetical scenario is achieved in 1 year and the whole assessment period is 10 years.

- The number of early preventable deaths per 100,000 population per year is highest in North East England (3.6 deaths per 100,000 people) and the West Midlands (3.3 deaths per 100,000 people).

Promoting active travel and investing in measures to improve infrastructure for walking and cycling can deliver significant health benefits.

- The World Health Organization’s (WHO) health economic assessment tool (HEAT) tool uses data from published meta-analysis on the relative risk of death from any cause among people who walk or cycle regularly, compared with those who do not. The average relative risk estimates derived from the studies are then applied to the level of walking and cycling specified by users.

- The calculations are performed separately for different age groups: 20 – 49 years and 50–74 years for walking; 20–49 years and 50–64 years for cycling. The age groups for analysis in the National Travel Survey are slightly different from those in the WHO tool and the calculations have been adjusted to account for this.

- A take-up time of 1 year is assumed before the projected level of walking and cycling is reached. The whole assessment period is 10 years, which means that the benefits accumulated over a 10-year period are summed up and presented as an average per year.

- Walking and cycling rates refer to miles of travel per person per day. The tool assumes an average speed of 5.3km/hour for walking and 14km/hour for cycling. The all-cause mortality rates assumed in the model are 434 deaths per 100,000 people for walking and 249 deaths per 100,000 people for cycling.

Further reading

Explore the topics.

Local authority dashboard Explore data for your local authority and neighbourhood

Health inequalities

Money and resources Poverty | Income | Debt

Work Quality | Unemployment | Security

Housing Affordability | Quality | Stability | Security

Transport Active travel | Social exclusion | Trends

Family, friends and community Personal relationships | Community cohesion

Share this page:

This is part of Evidence hub: What drives health inequalities?

Health Foundation @HealthFdn

- Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

The Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Quick links

- News and media

- Events and webinars

Hear from us

Receive the latest news and updates from the Health Foundation

- 020 7257 8000

- [email protected]

- The Health Foundation Twitter account

- The Health Foundation LinkedIn account

- The Health Foundation Facebook account

Copyright The Health Foundation 2024. Registered charity number 286967.

- Accessibility

- Anti-slavery statement

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

Healthy Cities Toolkit

Global Centre on Healthcare and Urbanisation, Kellogg College

Active travel

Moderate positive impact based on uncertain evidence with low resource implications

Cite as Heneghan C, Onakpoya I. Active Transport. Oxford Healthy Cities Toolkit

- Access data

Description

Active travel, also described as active transport or transportation, is defined as making journeys that involve a level of physical exercise [UK Dept for Transport, 2022 ].

It can include walking, cycling, skating or skateboarding (to name a few) and is highly favourable when commuting to work or school. In the literature, active travel was measured using self-reported instruments, surveys or questionnaires, interviews or focus groups, accelerometry, digital tracking devices or GPS.

Fourteen reviews considered the health impacts of active transport involving nearly 500 primary studies. Overall, active travel had a positive effect on increasing rates of physical activity, reducing non-communicable diseases, and improving mental health.

Designing community environments that make active travel convenient, safe, attractive, cost-effective, and environmentally beneficial is likely to produce the greatest impact.

The included reviews represented the ages of the general population, with one review focusing on children and young people [Audrey 2015 ], and two reviews on older people [ Barnett 2017 ; Graham 2020 ].

Three reviews restricted their geographical scope, with one review from the UK [ Graham 2020 ]’ Korea [ Kim 2019 ] and Latin America [ Gomez 2015 ].

Most (85%) reviews assessed rates of physical activity and examined the relationship of the urban environment in promoting active transport. Factors that supported active travel include:

- Adequate infrastructure (e.g. cycle lanes) and connection/continuity of cyclable and walkable surfaces [ de Carvalho 2012 ; Gomez 2015 ; Mölenberg 2019 ; Rachele 2019 ; Sallis 2015 ; Smith 2017 ; Stankov 2020 ]

- Smaller and calmer car traffic, offering greater safety for cyclists and pedestrians [ de Carvalho 2012 ; Gomez 2015 ]

- Short distances of trips [de Carvalho 2012 ; Gomez 2015 ; Sallis 2015 ; Stankov 2020 ]

- Aesthetics of the streets and facilities (cleanliness, low noise, presence of trees/greenery) [ de Carvalho 2012 ; Rachele 2019 ; Sallis 2015 ]

- Mixed land use, combining residential, commercial, and leisure spaces and facilities within a concentrated area [ Gomez 2015 ; Kim 2019 ; Rachele 2019 ; Sallis 2015 ]

- The financial cost and economic benefits [ de Carvalho 2012 ; Sallis 2015 ]

- The environment and sustainable mobility [ de Carvalho 2012 ; Gomez 2015 ; Sallis 2015 ]

Factors that discouraged cycling were related to geography (e.g. weather or terrain) and individual factors (e.g. age, sex, education levels). The lack of connectivity of cycling routes, zoning and land use distribution, and low petrol prices encouraged individuals to use cars. [ de Carvalho 2012 ]

Factors that both encouraged and discouraged active travel were dependent on socio-economic conditions and economic development, which drove the adoption of public policies. [de Carvalho 2012 ]. For example, in Australia, lower economic status was a factor that reduced the use of bicycles by children attending schools, whereas, in Brazil, lower socio-economic profiles were linked to higher rates of active travel when commuting to schools.

For children and young people, multi-component and single-component interventions deployed at schools increased students’ activity levels and reduced parental driving [ Audrey 2015 ]. Factors such as distance from home to school, infrastructure improvements (e.g. cycle lanes, calming traffic schemes), education, and non-car use at baseline influenced active travel.

For older adults, neighbourhood walkability, access to destinations and services and recreational facilities, crime/personal safety, residential density, walk-friendly infrastructure, street lighting, the presence of greenery and aesthetically pleasing scenery were positively associated with physical activity and walking. [ Barnett 2017 ; Rachele 2019 ]. In the UK, cost, availability, connectivity and infrastructure, such as benches and bus shelters, were crucial in enabling active travel among elderly individuals [ Graham 2020 ].

One review identified positive effects for people with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, breast and colon cancer, and dementia, as well as all-cause mortality and the incidence of overweight and obesity [Xia 2013 ].

One review focused on mental health and found that people who actively commuted to work (cycling/walking) reported improved mental health outcomes, but this effect was reduced after baseline mental health was accounted for [Moore 2018 ].

One review examined policies to promote active travel, which found that infrastructure is at the core of promoting active travel, but policies may work best when implemented in comprehensive packages [ Winters 2017 ].

Strength of the evidence

Strength of the evidence

Three reviews used a tool to assess the risk of bias or quality, which had moderate [ Barnett 2017 ], low [Moore 2018 ] and very low-quality evidence [ Audrey 2015 ].

The remaining 11 reviews were ranked uncertain, giving an overall rating of uncertain evidence.

Despite the uncertainty in the quality of the evidence, action should not be postponed until stronger evidence is developed, as the health, environmental, and economic benefits of active travel are clear.

Searches for evidence were conducted between 2010 and 2019 in a median of six databases. Ten of the included studies were formal systematic reviews (two with meta-analyses, one using mixed methods, and one with qualitative studies), three were literature reviews, and one was an overview of systematic reviews.

Resource Implications

Resource Implications

Resource implications were graded low because of the extent of the co-benefits afforded by active travel. In addition to positive health outcomes, reviews reported the economic and environmental benefits, including reducing traffic congestion, accidents, and air and noise pollution [ Graham 2020 ; Sallis 2015 ; Smith 2017 ; Winters 2017 ; Xia 2013 ].

One review estimated the combined economic benefit of eliminating short motor vehicle trips in 11 metropolitan areas in the upper mid-western USS to exceed $8 billion/year [ Xia 2013 ].

Micro-level interventions that increase attractiveness and convenience for active travel are low-cost and easier to implement than macro-level interventions for street design and layout [ Barnett 2017 ; Winters 2017 )].

The rising costs of car transport and petrol prices have reportedly increased the uptake of active travel [ de Carvalho 2012 ; Mölenberg 2019 ]. The implementation of economic incentives, such as congestion and parking fees, was found to promote active travel and significantly improve health [Stankov 2020 ].

Recommendations

- Increase investment in infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists to promote active travel.

- Use interdisciplinary teams involving those from the transport, planning, public health, and policy sectors should embrace opportunities to implement and evaluate active transport interventions.

- Invest in high-quality research, adjusting for residential self-selection, conceptually-driven choosing of built environmental attributes, and adjusting for key socio-demographic covariates.

- Research is needed to identify the optimal density threshold that supports active travel, which is important for informing planning policy and practice.

Related Resources

Related sources

- WHO (2018): Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018-2030 – More Active People for a Healthier World

- WHO (2020): Physical activity

- UK Department for Transport (2022): Active Travel – Local authority toolkit (guidance)

- UK Department for Transport (2020): Cycling and walking plan for England (policy paper)

- UK Department for Transports (2019): Future of Mobility – urban strategy (policy paper)

- Public Health England (2016): Active travel – a briefing for local authorities

- Healthy Places by Design (2001-2008): Active Living by Design

- Sustrans (2017): Active Travel Toolbox

- Open Streets Project

- Active Living Research: Tools and Resources

- Living Streets: UK Charity for Everyday Walking

- Choose how you move: A smarter way to travel in Leicester and Leicestershire

- Transport Scotland: Walking and cycling

- Imperial College London: Active travel

- National Walk to Work Day: UK Public Health Network

References to Reviews

References of Reviews

Audrey 2015. Healthy urban environments for children and young people: A systematic review of intervention studies. Health & place 36: 97–117.

Barnett 2017. Built environmental correlates of older adults’ total physical activity and walking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 14(1): 103.

de Carvalho 2012. Cycling to achieve healthy and sustainable alternatives . Ciencia & saude coletiva 17(6): 1617–1628.

Gomez 2015. Urban environment interventions linked to the promotion of physical activity: a mixed methods study applied to the urban context of Latin America. Social science & medicine 131: 18–30.

Graham 2020. Older people’s experiences of everyday travel in the urban environment: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies in the United Kingdom. Ageing & Society 40(4). Cambridge University Press: 842–868.

Kim 2019. How Does the Built Environment in Compact Metropolitan Cities Affect Health? A Systematic Review of Korean Studies. International journal of environmental research and public health 16(16). DOI: 10.3390/ijerph16162921 .

Mölenberg 2019. A systematic review of the effect of infrastructural interventions to promote cycling: strengthening causal inference from observational data. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 16(1): 93.

Moore 2018. The effects of changes to the built environment on the mental health and well-being of adults: Systematic review. Health & place 53: 237–257.

Rachele 2019. Neighbourhood built environment and physical function among mid-to-older aged adults: A systematic review. Health & place 58: 102137.

Sallis 2015. Co-benefits of designing communities for active living: an exploration of literature. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 12: 30.

Smith 2017. Systematic literature review of built environment effects on physical activity and active transport – an update and new findings on health equity. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 14(1): 158.

Stankov 2020. A systematic review of empirical and simulation studies evaluating the health impact of transportation interventions. Environmental research 186: 109519.

Winters 2017. Policies to Promote Active Travel: Evidence from Reviews of the Literature. Current environmental health reports 4(3): 278–285.

Xia 2013. Co-benefits of replacing car trips with alternative transportation: a review of evidence and methodological issues. Journal of environmental and public health 2013: 797312.

Climate & Environment at Imperial

Insights from staff and students across Imperial working in climate and environment related areas

Active travel: good for body, mind and the environment

Dr Madeleine Morris , Research Associate at the Grantham Institute, blogs on why walking and cycling is the way forward when it comes to local travel.

As the UK begins to emerge from lockdown, there has been much discussion about how we travel within our towns and cities, particularly for those who are returning to work. The Government is urging everyone to avoid public transport wherever possible to limit the spread of COVID-19, and to instead take alternative forms of transport. However, if everyone who normally took public transport were to jump in their cars there would be serious problems; cities could come to a standstill, pollution levels would rise significantly, and there could be an increase in injuries to road users and pedestrians alike.

‘Active travel’ – i.e. taking journeys by physically active means, like walking and cycling – is an excellent option for many people. It can reduce the risk of spreading viruses and has multiple benefits for the climate and public health. Local authorities across the UK are transforming streets to make them more accessible for pedestrians and cyclists. The Mayor of London, for example, has launched Streetspace , which aims to widen pavements and give much more space to new cycle lanes. So, there’s never been a better time to start!

I started cycling to work about five years ago because my commute was crowded, expensive and frequently delayed by late running or cancelled trains. The direct benefits for me were a more reliable and pleasant commute at a fraction of the cost, but since then I’ve taken note of the many other benefits, both direct and indirect, that come with active travel.

Big climate benefits

Road transport is responsible for around a fifth (21%) of the UK’s total greenhouse gas emissions. Switching to active travel modes, even for some of our journeys, is one of the most immediate and accessible ways to address this.

Better use of space

The average car is stationary for 95% of its lifespan. Fewer cars on the road means less space required to park them, so more land can be devoted to green space. ‘Parklets’, small parks that take the place of one or two parking spaces, can bring green space to our roadsides and urban areas. This would not only improve air quality but also help build community spirit by providing areas for people to come together on their doorsteps.

These green spaces can even help to keep cities cool and reduce flood risks by absorbing excess rain water. Implementing them at a larger scale, then, could help cities adapt to extreme weather made worse by climate change .

Cleaner air

Air pollution is the fourth biggest killer in the world, contributing to more than six million deaths every year. It is estimated that, on average, four Londoners – including one child – are hospitalised every day due to asthma caused by air pollution. Although avoiding roads with heavy traffic is beneficial, even London’s green spaces are affected by pollution. More than a quarter of the city’s parks , playgrounds and open spaces exceed international safety limits for air quality.

This puts huge pressures on our health- and social-care services. If we don’t reduce pollution levels, the costs to the NHS and social care in England alone could reach as much as £18.6 billion in the next 15 years . Now, more than ever, the importance of reducing pressures on these essential services has been made clear.

Switching to active modes of travel like walking and cycling are simple ways that many of us can contribute to cleaning up the air in our communities.

Good physical health

As well as allowing us to breath cleaner air, walking and cycling benefits our physical health by keeping us active. Many of us increasingly spend most of our time sitting down (especially at work), yet long-term physical inactivity has been shown to have negative effects on our health . Research shows that people who cycle to work, could reduce their chances of early death and cancer diagnoses.

In fact, the health benefits of cycling are so great that they outweigh any negative impacts of being more exposed to air pollution from surrounding vehicles. For me, an added bonus is that travelling by bike frees up time I would otherwise (begrudgingly) put aside to ‘do exercise’ to stay healthy. Who doesn’t love having more free time?

Healthy body, healthy mind

The last couple of months have shown us how important it is to take care of not just our physical health, but our mental health and wellbeing. Avoiding public transport could leave us feeling out of control and stranded from our friends, families and activities we enjoy. Cycling and walking can help us stay connected and, at the same improve our health. A study of seven European cities found that people who cycle in cities have better mental health, and feel less stressed and lonely, than those who travel by car or public transport. And it’s better for the planet.

For more on active travel, check out my top tips to get on your bike and enjoy cycling in the city .

For the latest news, views and events from the Grantham Institute, sign up to our weekly update newsletter .

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Published by Grantham Institute

Climate change and environment institute at Imperial College London, one of the world's leading research universities. View all posts by Grantham Institute

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from climate & environment at imperial.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

9 benefits of active commuting that will convince you to ditch the drive

D oes getting to work for you mean hours of sitting, mindless snacking and sipping on syrupy coffee in crowded trains or white knuckle traffic while you dream of the weekend so you can get back out in your hiking boots ? A 2021 study from Stockholm has revealed the damaging effects of commuting on health, such as physical inactivity, obesity and disturbed sleep, but for many of us, it doesn’t have to be that way. If you already love the outdoors, why not turn your commute into an active adventure on foot or bike? You can reap some incredible benefits for your health, your bank balance and the planet. Read on to discover nine great reasons to turn your commute active and some tips for getting started.

1. It can help you meet – or surpass – your activity goals

Even if you consider yourself really active, if you sit down to commute and you’re relying on trail time or gym sessions after work to meet your daily activity goals, it can be all too easy to have a hard day at the office, skip the gym and not get any physical activity that day whatsoever. You might think you’re going to make it all up on Saturday with a long hike, but then the weather thwarts your plans and before you know it, you’ve missed out on several days worth of exercise.

If your commute involves even 30 minutes of walking each way, however, you’ve already met the recommended daily allowance of exercise as recommended by the World Health Organization . If you actively commute to work and get in your evening workout on top, you’ve just banked even more activity hours to counter all that time spent sitting at work.

2. It reduces your risk of disease

According to the WHO’s recommendations, meeting their minimum daily allowance of physical activity is proven to help prevent and manage noncommunicable diseases such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, several cancers and hypertension while helping you to maintain a healthy body weight. Those are some serious dividends for simply opting for a different mode of transport, and don’t worry that your commute is too short – University of Cambridge researchers recently concluded that as little as 11 minutes of brisk walking a day is enough to lower your risk.

3. It can save time

Walking or running to work might seem nuts if it would take you an hour and you can catch the train and be there in 15 minutes – how can that save you time? But think about it this way: in the active model, you could leave the house around 8am and be home by 6pm, and have finished both your work and your workout(s) for the day. You’ve got the whole evening ahead of you to spend with family, cook, socialize or practice your needlepoint if that floats your boat.

In the passive model, you’re beholden to the possibility of traffic jams or the schedules of public transport. Even if it’s a 15 minute journey to work, chances are you don’t leave the house at 8:45am. In fact, you probably leave at roughly the same as you would if you were going on foot or two wheels (you want to grab that coffee to make the commute tolerable, after all) and get home at about the same time, only you still need to work out.

4. You can use your commute as training

You can definitely use an active commute as a way to meet the minimum physical activity recommendations and you’d see loads of benefits, but if you’re in training for a specific goal or event, like a half marathon , you can use your commute as part of your training. If your commute is on the long end, run it on Monday and Friday as your long run. If it’s shorter, do it more frequently and make it your easy or recovery run. In other words, make it about the activity itself, and not just the destination.

5. It’s good for your mental health

The physical benefits alone are probably persuasive enough for you to ditch the bus from time to time, but it also has been shown to have a positive impact on your mental health. A 2014 study on nearly 18,000 commuters found that switching from car to active travel improved psychological wellbeing, and showed that while a longer car commute decreased feelings of wellbeing, a longer walking commute further increased wellbeing.

6. You get that morning sunlight

At almost any time of the year, an active commute to work means you can get the benefits of morning sunlight , which can boost your vitamin D levels, reset your body clock and give you the anti-inflammatory benefits of those early morning (and evening) red rays.

7. It saves money

In a time where the price of everything is soaring, you might be looking to save money wherever possible. Cutting back on that tank of gas a week, parking fees, monthly bus passes or multiple train tickets can really add up quickly, plus you might save on those comfort items like lattes and newspapers that you rely on to comfort you during your train or bus journey. With all that extra money you can definitely treat yourself to a pair of new running shoes or a swanky GPS watch for all those extra miles you’re putting in!

8. The air is cleaner outside

If your commute takes you through a built-up area, you wouldn’t be the first to think that the air inside your car is safer than all those exhaust fumes outside, but a 2022 study by the University of Leicester found that the exact opposite was true. In fact, commuting by car in urban areas during rush hour can actually result in larger concentrations of pollutants for driver and passengers inside the vehicle compared to walkers or cyclists making the same journey. Get out and breathe the fresher air!

9. It helps the environment

Speaking of all those exhaust fumes, needless to say that ditching the car reduces your carbon footprint and helps the environment too, and that's something you can feel really good about. Public transportation is definitely a better option than driving or carpooling, but nothing is greener than hopping on your bike or pulling on your running shoes.

How to get started as an active commuter

If you’re ready to give active commuting a go, you need to decide how you’re going to get there – will you walk, run, bike, or do something wild like roller blade or cross country ski? It might take a little trial and error, so leave plenty of time for your first journey and take some time planning your route.

In planning your route, you might just go for the most direct pathway, but consider making use of rec paths such as riverside and canal paths where you can get away from the traffic, stick to safer, well-traveled routes and consider going through green spaces like parks for a nature fix, too.

There is some gear that’s worth investing in to make your active commute comfortable, too:

1. Activity-specific backpack

You might not need to carry all the usual gear you need for a hike or trail run, but you’ll probably need to bring your work clothes and possibly your laptop, so invest in a running backpack like the Montane Trailblazer LT 20 if you’re going fast, a hiking backpack such as the Osprey Talon Earth 22 or a backpack that’s suited to your activity and expands to fit your gear.

2. Waterproof gear

Getting soaked isn’t as dangerous heading through town as it is at 14,000 feet above sea level, but arriving at work looking like a drowned rat might not be your ideal start to the work day. Get an activity-specific waterproof jacket like the North Face Lightriser Futurelight for running or the Montane Phase Lite for walking that will seal out a downpour, pack down small if it’s sunny and can go with you up a hill too.

It can be a good idea to stash a microfiber camping towel at the office too so that whether you get drenched or take a shower upon your arrival, you can towel off and it will dry quickly for next time.

3. Great footwear

If you’re heading to work on foot, it’s worth investing in good footwear to support your joints. Check out the best road running shoes for tarmac surfaces whether you’re planning on running or walking – you can leave your loafers or ballet flats at the office and change into them when you arrive.

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Driving and road transport

- Cycling and walking

Active travel: local authority toolkit

- Department for Transport

Updated 10 August 2022

Applies to England

© Crown copyright 2022

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] .

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/active-travel-local-authority-toolkit/active-travel-local-authority-toolkit

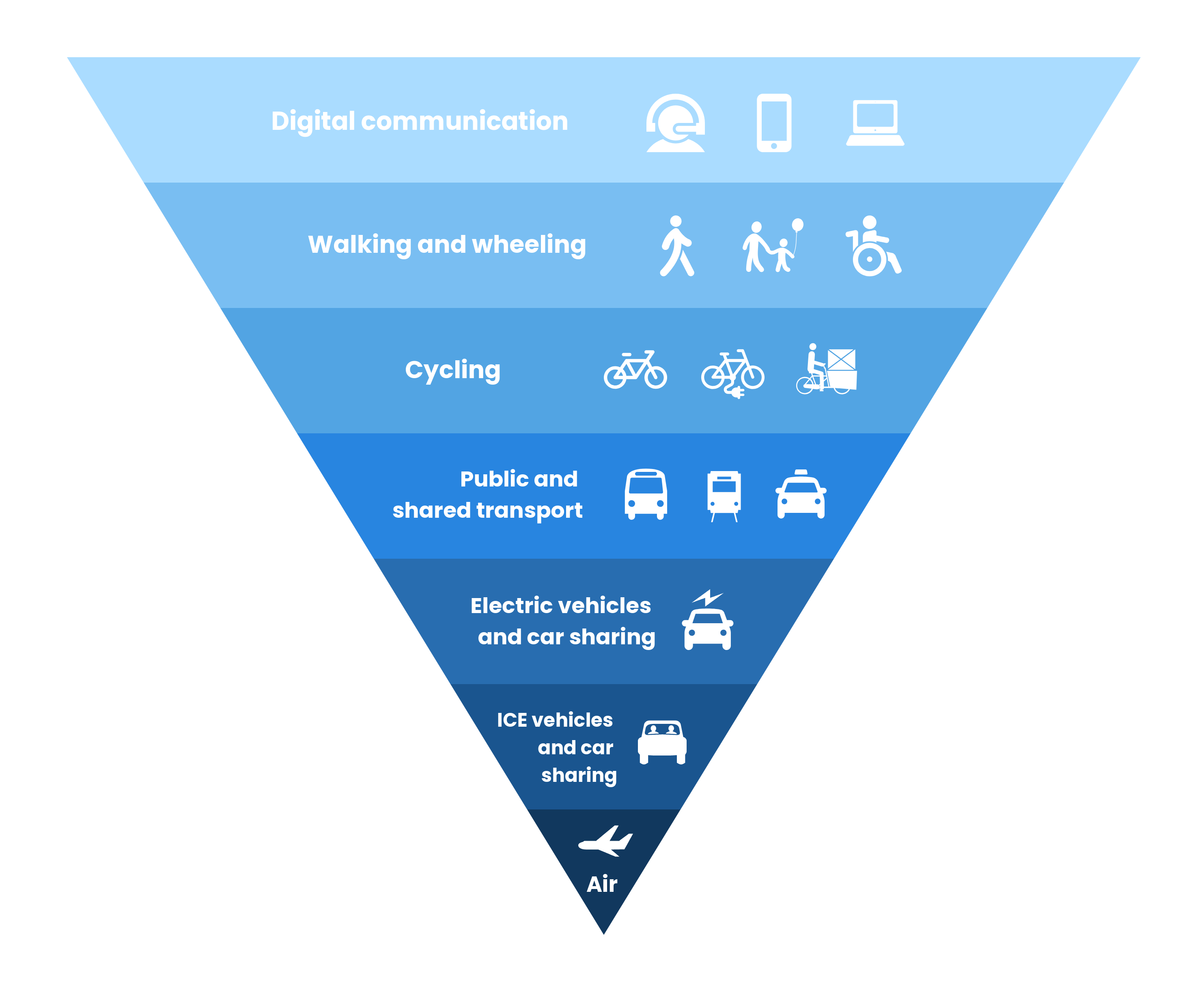

Walking, wheeling and cycling are the least carbon-intensive ways to travel.

However, walking currently accounts for only 5% of the total distance travelled in England. Around 49% of trips in towns and cities under 5 miles were made by car in 2021, with around a quarter of all car trips in England less than 2 miles.

Many of these trips could be walked, wheeled or cycled, which would help to reduce the 68 megatons ( Mt ) carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emitted from cars in 2019. This would benefit local economies, as well as improve people’s health.

More active travel will also make roads quieter, safer and more attractive for people to walk, wheel and cycle – a virtuous cycle.

As we decarbonise transport, making all cars, public transport and heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) zero emission is part of the solution, but relying solely on zero emission road vehicles isn’t enough.

Road traffic, even on pre-COVID-19 trends, was predicted to grow by 22% from 2015 to 2035, much of it in cities where building new roads is physically difficult and disadvantages communities.

As set out in the second cycling and walking investment strategy (CWIS2), the government wants walking, wheeling and cycling to be the natural first choice for shorter journeys or as part of longer journeys.

Local authorities can play an important role in increasing walking, wheeling and cycling. Through influencing planning and taking a wider, strategic view of travel infrastructure across their area, authorities can ensure that active travel infrastructure connects residents to services.

As local leaders, authorities have a wide sphere of influence and can lead by example in adopting, promoting and providing infrastructure to enable and encourage active travel with their staff.

Authorities can also work with local businesses, industrial estates and business improvement districts to design specific interventions and behaviour change programmes to enable active travel with their employees and customers.

The primary actions for local authorities are to:

- develop Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plans (LCWIPs)

- develop and implement Travel Demand Management Plans

- plan for and improve active travel infrastructure

- promote behaviour change to enable active travel

What active travel means

Active travel refers to modes of travel that involve a level of activity.

The term is often used interchangeably with walking and cycling, but active travel can also include trips made by wheelchair, mobility scooters, adapted cycles, e-cycles, scooters, as well as cycle sharing schemes (adapted from the definition in the Future of Mobility: urban strategy .

Wheels for Wellbeing explains that cycling includes a wide range of cycle types, including:

- recumbent tricycles

- cycles for 2 (tandem, side by side, wheelchair tandem and duet bikes)

Recent changes in active travel

The 2021 National Travel Survey found that the number of walking trips remained at a similar level to 2020, which is below the level seen in recent years prior to the pandemic. Whilst overall levels of walking have fallen in recent years, people are choosing to walk further, with walking trips of over a mile remaining higher than pre-pandemic years.

Cycling decreased back towards pre-pandemic levels, following a peak during 2020. The National Travel Survey reported that:

- 47% of people over 5 years had access to a pedal cycle, the same level as 2020

- less people (a decrease of 27%) cycled for part of their trip, and the average number of trips by cycle decreased by 27%

- following the peak of average miles cycled per person in 2020, average miles decreased by 37% in 2021 – bringing it back to pre-pandemic levels

Wave 5 of the National Travel Attitude Survey focused on cycling with:

- off-road and segregated cycle paths (55%), safer roads(53%) and well-maintained surfaces (49%) the most common measures that respondents said would encourage them to cycle more

- 64% supporting the creation of dedicated cycle lanes, at the expense of road space for cars

E-cycles are growing in popularity and make cycling accessible to more people, build users’ confidence and enable cycling in more challenging terrain.

The definition of e-cycle includes all electrically assisted pedal cycles, electric cycles, e-bikes and e-trikes.

E-cycles offer assistance only when the rider is pedalling and must comply with the electrically assisted pedal cycles (EAPCs) regulations .

To be classified as an EAPC and not treated as a motor vehicle, when used on roads, a cycle fitted with an electric motor must comply with the requirements of the EAPC Regulations 1983. Specifically:

- it must be fitted with pedals that are capable of propelling it

- the maximum continuous rated power of the electric motor must not exceed 250 watts

- electrical assistance must cut off when the vehicle reaches 15.5 miles an hour

Cycle sharing

Cycle sharing describes any setting where cycles can be borrowed by the public or an employee (for workplace schemes).

Cycle sharing schemes can be an effective way to re-engage people in cycling – in CoMoUK’s 2021 bike share report nearly half of the 4,000 respondents said that joining a scheme was a catalyst to them cycling for the first time in at least a year, and 24% of them had not cycled for 5 years or more.

CoMoUK offers more information and guidance on cycle sharing schemes and identifies different scheme types:

- public – growing rapidly, these can include e-cycles. They integrate well with other modes of transport and are established in Belfast, Brighton, Cardiff, Glasgow, Liverpool and London and smaller locations such as Hereford, Guildford, and Stirling. Existing schemes in the UK can be found on CoMoUK’s map

- station-based – cycles are located at train stations and at various points across the town or city, at staffed or unstaffed hubs, docking stations or in a geo-fenced area. Some can be returned to any dock and others must be returned to the starting location

- free-floating – where cycles can be left anywhere within the urban boundary, often with guidance on not causing obstructions when parking

- cycle libraries – allow users to rent cycles for short periods and include cycle hubs in community locations (such as libraries and sports centres)

- peer-to-peer – where owners rent their cycle out for a fee

- pool cycles – generally housed at workplaces or community locations and borrowed by members of staff or the community. These schemes may share public facilities such as cycle storage

Implementing active travel: cycle sharing in Scotland

In 2020, the grant programme Paths for All, Smarter Choices, Smarter Places , in Edinburgh and Glasgow, worked to increase the uptake of cycle-sharing. This generated almost 18,000 new users and a 38% increase in trips in 3 months.

Users reported an improvement in their physical and mental health, and 10% went on to buy their own cycle. Further details are available from CoMoUK .

The benefits of active travel

Encouraging mode shift to walking, wheeling and cycling is one of the most cost-effective ways of reducing transport emissions, as outlined in the transport decarbonisation plan.

Walking, wheeling and cycling can decrease congestion, air and noise pollution, and both are linked to health and economic benefits.

Friends of the Earth produced a briefing on the role and benefits of segregated cycleways and e-cycles in urban areas. They report that improvements could deliver benefits for health, carbon and local economies, and make recommendations to maximise the effectiveness of funding.

Carbon emissions and air pollution

Sustrans, the national travel charity, estimates that 28,000 to 36,000 early deaths occur each year in the UK due to air pollution worsening heart and lung disease. They report that 80% of roadside nitrogen dioxide ( NO2 ) pollution is from road transport where limits are being broken.

As more of our short journeys (48% of all trips in urban towns and cities are under 2 miles) are walked or cycled, the carbon, air quality, noise and congestion benefits will be complemented by significant improvements in public health and wellbeing.

It is estimated that active travel can deliver between 1 MtCO2e and 6 MtCO2e savings from 2020 to 2050 in the transport decarbonisation plan.

In cycle share schemes, an average of 53kg of CO2e are saved per cycle share user each year according to CoMoUK’s 2021 bike share report .

Active travel can reduce the proportion of people driving children to school by up to 33%. Through projects such as the Big Pedal , 8.5 million car miles could be saved, resulting in a decrease of 2,500 tCO2e and reductions in NO2 levels.

Future active travel spending is expected to deliver £20 million to £100 million savings from air quality improvements as well as providing opportunities to improve green space and biodiversity.

Physical health

Physical inactivity costs the NHS up to £1 billion each year , with additional indirect costs of £8.2 billion according to a report by the Department for Transport ( DfT ) in 2014 on the economic benefits of walking and cycling . This report also highlights a link between adult obesity levels and travel behaviour as countries with the highest levels of cycling and walking generally have the lowest obesity rates.

In Growing Cycle Use , the Local Government Association ( LGA ) reports that if cycling rates were elevated to London levels across other UK cities, this would avoid at least 34,000 incidences of 8 life-threatening conditions between 2017 and 2040.

Regular commuting by cycle is linked to a lower risk of cancer or heart disease compared to other forms of transport. This may be partly due to cyclists and walkers being exposed to less air pollution than drivers and passengers inside vehicles on the same routes.

In the 2021 bike share report , CoMoUK found that 20% of cycle share scheme users said that if formed ‘all’ or a ‘major part’ of the physical activity they undertook.

Sustrans identifies further health benefits: a 3-mile commute will achieve recommended levels of activity each week.

The Energy Saving Trust reports that walking strengthens muscles, lungs, bones and joints.

Physical activity has also been shown to reduce incidences of heart disease, asthma, diabetes and cancer , as well as benefiting those with bad backs.

Mental health

Exercise can protect against anxiety and depression, according to the NHS . Any exercise is beneficial but exercising outdoors can have additional benefits.

Research in the British Medical Journal suggests that exercise can also help reduce stress . Guidance from the UK Chief Medical Officers’ on physical activity suggests that 30 minutes of moderate activity per day almost halve the odds of experiencing depression .

Gear Change states that completing 20 minutes of exercise each day cuts the risk of depression by 31% and increases worker productivity.

Economic benefits

Increasing active travel will reduce road congestion, particularly at peak times, leading to increased productivity and improved movement of goods and services. Sustrans estimates that congestion costs £10 billion per year in 2009 in urban areas, and that this cost could rise to £22 billion by 2025.

Living Streets’ Pedestrian Pound report outlined a range of economic benefits of walking, including that well-planned walking improvements can lead to a 40% increase in shopping footfall.

The LGA highlights how, after a Canadian council reallocated high street parking as bike lanes or cycle parking for a year, businesses benefitted from increased footfall (20% increase), spend (16% increase) and increased frequency of return visits (13% increase).

The Transport decarbonisation plan states that cycle manufacture, distribution, retail and sales contribute £0.8 billion per year to the economy and support around 22,000 jobs.

For organisations

As an employer, promoting active travel can help with corporate social responsibility, reduce the impact of business traffic (including commuting) locally and reduce demand for parking spaces.

Active travel can also improve the health and wellbeing of staff, increase productivity and motivation, and aid the recruitment and retention of skilled workers. More information is available on the Sustrans website .

Actions for local authorities

Local authorities are well placed to plan and provide space for inclusive active travel infrastructure and accompanying behavioural change programmes. For Local Transport Authorities (LTAs) and combined authorities, doing so is part of their responsibilities on highways and road safety.

The LGA , as part of their decarbonising transport series, produced guidance on how authorities can grow cycle use. They note that measures will be most effective if implemented as part of a comprehensive active travel plan, integrated with wider transport, climate and housing strategies.

The final evaluation report of the Cycle City Ambition programme makes suggestions for local policymakers and practitioners on the most effective ways to increase active travel. It found that improving infrastructure is effective in increasing cycling and improving health equity, but requires significant investment and may take some time for impacts to be fully realised.

Sustrans can assist local authorities to develop active travel policy and guidance. It can also help promote active travel and provide feedback on walking and cycling schemes. Its website has sections for professionals, policy, and a resource library to enable authorities to make the case for active travel.

Living Streets can offer specialist advice and support for local authorities on enabling walking, including school and community engagement and infrastructure design.

Wheels for Wellbeing is a national charity that supports disabled people to access and enjoy cycling. As part of its Infrastructure for All campaign , it has highlighted the most significant barriers to cycling for disabled cyclists, including inaccessible cycling infrastructure and inadequate facilities to secure adapted cycles.

It recommends that authorities looking to install or upgrade cycling infrastructure follow LTN 1/20 – Cycle Infrastructure Design Guidance or the London Cycling Design Standards inclusive cycle concept.

Wheels for Wellbeing has published a Guide to Inclusive Cycling that promotes best practice in designing inclusive cycling infrastructure.

Implementing active travel: Greater Manchester

Using funding from the Cycle Cities Ambition programme, Greater Manchester built 3 miles of cycle lanes along one of the city’s busiest bus routes in 2017 .

Infrastructure installed included a mix of on-road and fully segregated cycle lanes and shared-use paths, along with 26 bus stop bypass lanes for cyclists.

The cycling measures were planned as part of a holistic design to improve the environment and maximise opportunities for cycling, walking and improved bus travel along the corridor.