Tour De France Average Watts: The Easy Definitive Guide for 2023

Tour de France average watts

Over the years, Tour de France cyclists have averaged speeds of about 40mph or about 25 km/h. During the normal flat stages of the tour pro riders can usually average between 230-250 watt s which is equal to burning about 900 calories each hour.

Pro cyclists on the tour will usually average more than 300 watts or about 1100 calories an hour. For instance, Tadej Pogacar who won the 2021 race has a Functional Threshold Power of 415 watts which is the power he can sustain for about an hour’s riding.

However, it is important to note that for explosive one-hour climbs, some Tour de France riders have been known to exceed an average of 500 watts. In the final stages of a sprint for the finish, some cyclists have even hit maximal efforts averaging more than 1500 watts.

How Many Calories Do Tour de France Cyclists Burn?

Why power measurement is important, how many watts does the average cyclist put out, how many watts can a pro cyclist maintain.

Top cyclists at the Tour de France who compete in all 21 stages burn about 120,000 calories or an average of about 6000 calories for every stage. On some of the more difficult mountain stages, racers can sometimes burn up to 8000 calories.

To make up for the huge losses in energy during the rides, cyclists usually eat all manner of delectable treats such as energy bars, jam rolls, and mouthwatering gels so that they can get fueled up without chewing.

In earlier days, we had to measure cycling performance using either heart rates or miles per hour. During the early 1990s, cycling switched to measuring power output in watts.

Since that tie companies such as Ergomo, Powertap, and SRM have been producing power meters to measure the deflection of the crank arm using a specialized wheel hub or minuscule gauges that enable the more precise measurement of power output.

Most devices measure power output in watts with the key statistic being watts per kg of the body weight of the cyclist usually abbreviated as (W/kg).

This makes it easier to measure training intensity as compared to speed which may be more related to wind and terrain. While heart rates may offer a rough gauge, they usually vary in response to factors such as exercise duration, temperature, caffeine intake, humidity, fatigue, altitude, and hydration.

Power measurement is thus important as it measures the energy that is being delivered to the pedals thus measuring the intensity of work in watts. Measuring power thus makes it possible to monitor training and characterize the course of training, assess aerodynamic drag and sleekness, and also assist in pacing.

A beginner cyclist will average about 75-100 watts during an hour’s workout. A fit athlete will usually average more than 100 watts in an hour while a pro cyclist will consume more than 400 watts during an hour’s riding.

The typical cyclist will produce an average of 310 watts of power in a minute of riding.

A professional cyclist can usually average a power output of about 400 watts during a race. However, cyclists have been known to produce higher outputs of more than 1000 watts for short periods of time such as the final sprints .

In terms of watts per kg the average professional cyclist riding in the Peloton can produce about 6.15 W/kg assuming they weigh in at about 70 kg.

The average cyclist will usually maintain an average power output of about 163.8 watts for about 20 minutes while the professional cyclist will be able to maintain a wattage of about 429 watts.

While the untrained rider can only manage 20 minutes of riding at close to their maximum effort before benign totally exhausted the professional cyclist riding in a Peloton at the Tour de France would just shrug that off and keep riding.

Related posts:

- Average Cycling Speed By Age Chart: With 3 Easy Hacks to Increase SPEED in 2023

- How Fast Can A Bike Go Downhill: 8 Best Tips to Descend Safely in 2023

- How To Improve Cycling Speed and Endurance: 5 Tips to Increase Speed in 2023

- Why Am I Getting Slower At Cycling: 5 Simple Reasons in 2023

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

CURRENT PRICES END MAY 12

Outside Festival feat. Thundercat and Fleet Foxes.

FROM JUST $44

Powered by Outside

Tour de France

Tour de france power: the numbers behind vingegaard’s tt and sepp kuss on the col de la loze, literally no one expected vingegaard to beat tadej pogačar by one minute and 38 seconds in stage 16’s time trial..

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

In this column, we dive into the power numbers of the world’s best riders at the Tour de France .

No one expected this. Not a single person in the entire world – not even Jonas Vingegaard himself – thought that Vingegaard would beat Tadej Pogačar by one minute and 38 seconds in stage 16’s time trial.

In the first 15 stages of this year’s Tour de France, Jonas Vingegaard and Tadej Pogačar had been neck and neck. The duo had dropped each other once or twice and taken a few bonus seconds here and there. But coming into the time trial, most experts predicted Pogačar or Vingegaard would beat the other by a handful of seconds.

Without hyperbole, the time trial that Jonas Vingegaard executed on stage 16 was arguably the greatest time trial performance in cycling history. That includes all eras, riders, climbs, and comebacks. It was hard to believe the live timing as the results flashed across the bottom of the screen.

“20 seconds faster” than Wout Van Aert in the first 4km of the stage 16 time trial. How is that even possible?

It was true, and Vingegaard was already 31 seconds ahead of Pogačar at the base of the Côte de Domancy. While we don’t have Vingegaard’s power data, we can see from his speed that he was already head and shoulders above the rest of the Tour de France field.

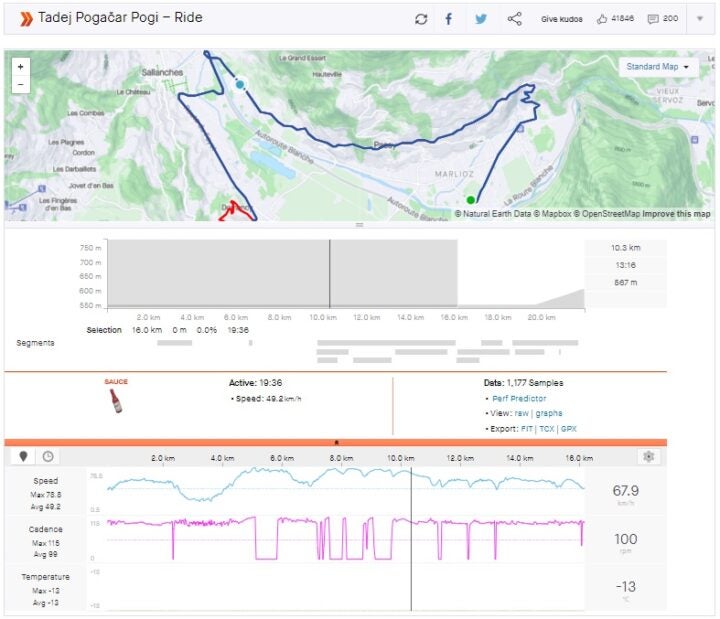

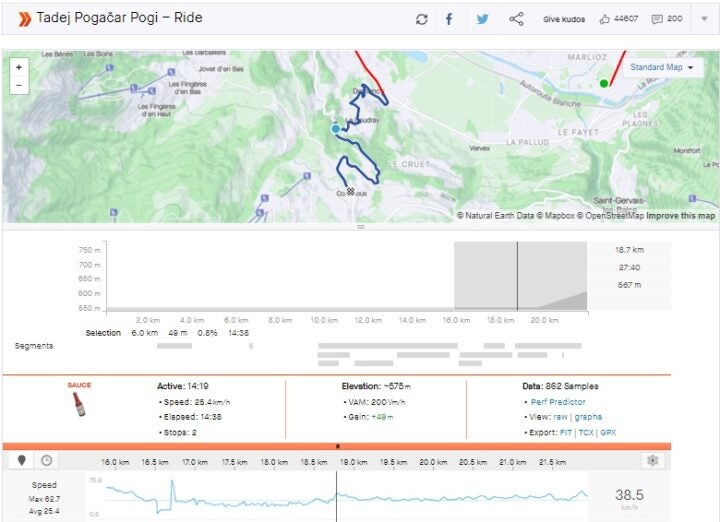

Vingegaard – Start to T2 (Second time check) Time: 19’ 05” Average Speed: 50.6 kph (31.4 mph)

Pogačar: 19’ 36” at 49.3 kph

Next was the climb to the finish at Combloux, which began with the Côte de Domancy (2.8km at 8.5%). After 19 minutes of riding full gas on the TT bike, Vingegaard produced the most insane climbing performance I’ve ever seen. There is no comparison to the power and speed that Vingegaard did on the climb to Combloux.

The 26-year-old Dane pushed ~7.5w/kg for over 13 minutes on his time trial bike, which is one of the most incredible performances in cycling history.

Vingegaard – Climb to Combloux Time: 13’ 21” Average Power: ~7.5w/kg

Pogačar: 14’ 38” at ~6.7w/kg

These power values were estimated using a variety of data, including years of historical power data from this exact climb to Combloux. The exact power numbers will never be 100%, especially when you consider calibration factors, temperatures, power meter brands, and more. But all that matters is that Jonas Vingegaard went insanely fast up the climb to Combloux, and I can say with 99.99% certainty that he did well over 7.3w/kg for 13 minutes…after already time trialing at 50.6 kph for 19 minutes.

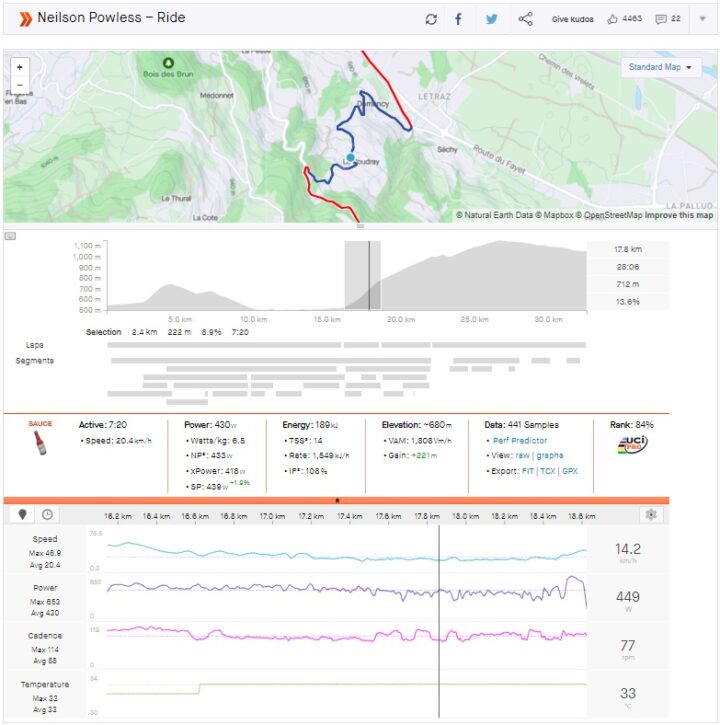

Neilson Powless went full gas on the Côte de Domancy in an attempt to gain points in the KOM classification. The American ended up going one second faster than Pogačar on this segment, though the Slovenian did a bike change, which cost him roughly 10-12 seconds. Vingegaard was 33 seconds faster than Powless and did not do a bike change, which meant that the Dane was riding his heavier TT bike up the 11% grades. That meant that Vingegaard was putting out even more power relative to Powless, who was on an ultra-light road bike.

Powless – Côte de Domancy Time: 7’ 20” Average Power: 430w (6.5w/kg)

Vingegaard: 6’ 47” at ~7.5w/kg

Pogačar: 7’ 21” at ~6.5w/kg

No one in the world thought that Jonas Vingegaard was capable of a performance like this. His team was confident in him, but I’m sure they were shocked when the time gaps popped up on screen. Vingegaard won the Stage 16 time trial with a time of 32 minutes and 26 seconds, 1:38 faster than Pogačar in second, and 2:51 faster than Wout Van Aert in third.

Jumbo-Visma has had to answer a lot of questions in the last few days, as can be expected in the sport of cycling. Mathieu Heijboer, Jumbo-Visma’s Head of Performance, said that Vingegaard did seven months of preparation for this TT, including three sessions a week on his time trial bike. The team also used data from the O Gran Camiño and Critérium du Dauphiné time trials to help plan Vingegaard’s Stage 16 effort.

The Jumbo-Visma team directors actually feared for Vingegaard when he flew out of the start gate and took 16 seconds by T1. At the Critérium du Dauphiné, Vingegaard went out too hard in the 31.1km time trial with an incredibly similar course profile to Stage 16 of the Tour de France. On that day, Vingegaard was fastest at T1 by 12 seconds, but then lost his legs and ended up finishing 2nd on the stage behind Mikkel Bjerg.

But on Stage 16 of the Tour, Vingegaard had the best legs of his life. He thought his power meter was broken, he said in a post-race interview, because the numbers were so high. However, the data suggests that Vingegaard had one of his best rides ever – you could even say it was one of the greatest cycling performances of all time.

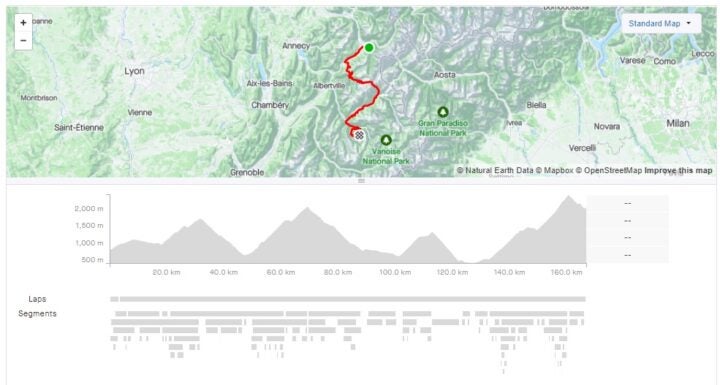

Ever the sportsman, Vingegaard said, the Tour isn’t over until it’s over (basically) – next was the queen stage of the 2023 Tour from Saint-Gervais Mont-Blanc to Courchevel. The stage included over 5,300 of elevation gain in 166km, including a summit finish atop the longer version of the Col de la Loze at 2,300 meters. Jumbo-Visma said that their original plan had been to attempt to crack Pogačar on this stage, but would that change after Vingegaard took nearly two minutes in the TT?

After a massive breakaway formed in the first half of Stage 17, Jumbo-Visma began pacing hard on the second climb of the day, the Cormet de Roselend (19.8km at 6.1%). The peloton shrank to just a few dozen riders, and that pce continued on the penultimate climb of the Côte de Longfoy (6.7km at 7.5%).

As the peloton hit the lower slopes of the Col de la Loze (28.3km at 6%), Pogačar began drifting to the back of the group. Not long after, he fully unzipped his jersey and seemed to be struggling. The only other time I remember seeing Pogačar fully unzip his jersey was on the hot, high-altitude climb to Granon, where Vingegaard famously cracked Pogačar to win the 2022 Tour de France.

Just a few kilometers later, Pogačar was dropped. Vingegaard and his super domestique, Sepp Kuss, could hardly believe their eyes as they kept turning around to find Pogačar. But the Slovenian was long gone, and he would eventually finish 22nd on the stage, over five minutes behind Vingegaard.

Despite his rivals already being minutes behind him, Vingegaard attacked on the Col de la Loze, dropping every one of the GC contenders and starting to challenge for the stage win. Up front, Felix Gall put on a climbing clinic, holding an estimated 6.1w/kg for 34 minutes on the way to his first-ever Grand Tour stage win.

Vingegaard went more than a minute faster than Gall over the final 11.2km of the Col de la Loze, despite getting momentarily stuck behind an official’s car.

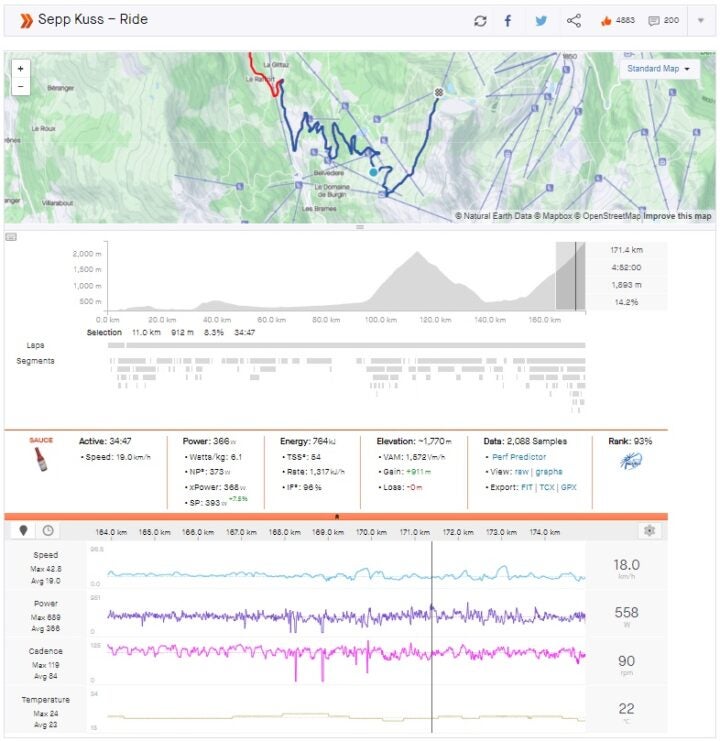

Back in 2020, the Tour de France raced up this same section of the Col de la Loze, where Miguel Ángel López took the win ahead of Primož Roglič and Pogačar. Sepp Kuss was 4th on that stage, and he posted his power to Strava. The American did 6.1w/kg for over 34 minutes during that effort but was ~40 seconds slower than Gall’s 2023 time.

Kuss – Col de la Loze 2020 Time: 34’ 47” Average Power: 366w (6.1w/kg)

Gall: 34’ 05” at ~6.1w/kg

Vingegaard: 33’ 00” at ~6.3w/kg

*** Power Analysis data courtesy of Strava

Strava sauce extension

Tadej Pogačar

Neilson Powless

Popular on Velo

What’s it like to be an American cyclist living in France? Watch to get professional road cyclist Joe Dombrowski’s view.

Related content from the Outside Network

One way south, mountain bikers react to their first taste of non-alcoholic craft beer, video review: bmc urs 01 two gravel bike, kiel reijnen vuelta video diary: the painful decision to abandon.

Greg Henderson's Tour de France Power Data

Forme Coaching analysis from stages 4, 6 and 9

Rider Profile : Greg Henderson Height: 1m 81 Weight: 70kg

Forme Coaching analysis of racing: Paris-Nice 2012

Forme Coaching analysis of racing: Tirreno Adriatico

Forme Coaching analysis of racing: La Flèche Wallonne

Tour de France Stage 4: Abbeville - Rouen 214.5km Greipel wins Tour de France stage in Rouen

The stage was a perfect opportunity for the sprinters and their teams to make a mark on the race as every opportunity to strike out on a result in this extremely hard fought Tour is not one to be missed. So the nervousness and anxiety of a swelling and erratic peloton in the last 20km of a Tour de France stage is not a place for the faint hearted, cue the lead out men who have the job to not only chaperone their team leader but also put their limbs on the line in the process. Who better to do this job than prolific winner in his own right, Greg Henderson , who is partaking in his first Tour de France in the service of André Greipel of Germany. Greg has been racing at the top level of the sport for many years and has the tag of one of the best lead out men in the business and we now have the power files to confirm his strengths along with the results this formidable Lotto-Belisol team have gained so far in this years Tour.

The data shows that for the first three hours of the stage Greg had an average power of 146 watts which is below his endurance range, proving that the initial 100km on the stage was a conservative affair for this lead out man whose mindset was on the race final and making sure had all his bullets left to use come 10km to go. So for these reasons we can see that he has done a perfect job to conserve his energy for the final kilometres. The fireworks really started in the last 25km of the stage and fighting for position is the priority and keeping your sprinter and GC riders out of harm's way, this is seen by Greg’s average speed of 49kph in the section from 25km to 10km to go approximately - with an average power of 231w (260w Normalized) and 3.3w/kg, the effort was starting to ramp up as you would be expected coming into the final of this stage.

With an increase of nearly 2 watts per kilo difference between those two sections you can see that a major concerted effort was made by the Lotto-Belisol team to keep Greipel out of danger and using the initial lead out men to keep the pace high at or near the front. This proved to be a excellent move to take the reins at the front of the bunch as a major crash just 15 riders back from the front at 2.7km to go caused major chaos for some of Greipel’s main adversaries, but this left Greg and his team in a excellent position to finish the job as the pace was at a level that no one was going to take over there dominant position at the head of the bunch while the chaos of the crash behind was casing havoc to the other lead out trains and sprint favourites. At this point Greg was still sitting on the wheel of his fellow lead out men sitting at a cool 60kph.

From this you can see an average close to 60km per hour in this last kilometre with Greipel having to come off his teammate's wheel and starting his own sprint as Greg was hitting close to 68kph.... Amazing to say the least having to start a winning sprint while your lead out man is sitting at 68kph! Greg’s cadence averaged 109rpm which shows his ability to hold a high sustained cadence producing a maximal effort, an early career schooling on the track showing it’s benefits here. A max effort of 1150w for a guy of 70kg is a power to weight of 16.5 w/kg at the tip of this text book lead out. A very high anaerobic effort produced after a solid previous 20min gradual rise in speed and power.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Aurthor: Dan Fleeman - Director Forme Coaching

Sometimes watching a bike race doesn’t do justice to how hard a sport cycling really is.

In football and other pitch-played sports, if a player falls over or is injured, they simply substitute him and bring on a replacement.

But when a bike rider hits the deck at 50+kph he is expected to jump straight back on, chase after the bunch, rejoin the race and in some cases contest the finish, no matter what injuries they’ve incurred.

In a lot of cases the true nature of the injuries will not be fully understood until the rider has finished the race and gone off to hospital. It’s hard to imagine a footballer finishing a game before going to hospital to see if his leg is broken.

It’s even been known for riders not to go to hospital because they think they have a broken bone; but don’t want it to be confirmed because it would mean they may not be able to start the next day. They feel it’s better to cope with the pain, finish the race and then get it treated once the race is over. Stage six of this year’s Tour saw the riders cover 207.5 km from Epernay to Metz.

It was the last flat stage before the riders headed into the mountains and with it being a flat parcours, many would expect a straightforward stage which would end with a bunch sprint - but this is the Tour de France - and there was nothing straightforward about the stage.

A massive crash 25 km from the finish saw the GC hopes of some top contenders like Ryder Hesjedal ended and those of others such as Frank Schleck and Robert Geslink, severely damaged. As the break was still ahead of the bunch when the big pile up happened, the bunch could not afford to slow and wait, with a lot of GC contenders and some sprinters left behind.

In fact only 60 riders were left to contest the bunch sprint in Metz. One rider who had made his way back after crashing was Andre Greipel; he was in a lot pain due to a dislocated shoulder and sprained wrist sustained in the crash and didn’t want to contest the sprint.

But his Lotto-Belisol teammates, including loyal lead-out man Greg Henderson - who had done so much work for his team leader all week – talked the German into contesting the finish. It was business as usual as the Lotto-Belisol boys hit the front in the closing kilometres to form their famous sprint train.

Even with such severe injuries, the German power house almost pulled off his third stage win; but this time he had to settle for second behind the very much in form Peter Sagan. The first three hours were relatively easy for Greg, with an average power of 179 watts and a normalized power of 244 watts he was effectively riding in zone 1/2 the entire time.

The low average speed of 37.7kph shows that the peloton was prepared to take it easy while the breakaway got on with the job at hand.

Into the fourth hour things started to get serious with the speed up to 46kph average and a few rises in altitude giving an average watts of 230 and a normalized power of 285 watts; for Greg with an FTP of 375 watts this is right in his zone three, so in other words a fast sustained tempo.

The final hour saw the pace pick up to a rapid 52kph average with the final 30 minutes average over 55kph. All Greg’s peak powers for the stage came in this final hour with Greg performing six efforts of over 900w inside the final 2.5 kilometres with his team taking control of the front of the bunch.

Greg hit the front inside the final 500m and averaged 66kph for 300m before dropping Greipel off with 200m to go - and getting so close to win number three.

960w for 18 seconds and a max speed of 67.6kph and max power of 1230w after 5.25 hours racing is seriously impressive power. See the full file here .

Final Lead-out: 18" 960 W Avg, 1230 W max 5:15:24 - 5:15:42 Total Time:0:00:18 Distance:0.33 km Energy:17 kJ TSS: W/Kg:13.7 MIN AVG MAX Power (Watts): 443 960 1230 Speed (km/h): 61.0 66.0 67.6 Pace (min/km): 00:59 00:55 00:53 Cadence (rpm): 104 109 111 Elev (m): 247 248 249 Temp (C): 24 24 24

Greg Henderson’s Race data Tour de France Stage 9: Arc-et-Senans - Besançon (ITT) 41.5km 1 Bradley Wiggins (GBr) Team Sky 0:51:24 2 Christopher Froome (GBr) Team Sky 0:00:35 3 Fabian Cancellara (Swi) RadioShack-Nissan 0:00:57 137 Greg Henderson (NZl) Lotto Belisol Team 0:07:40

The TT: Greg has a threshold of 375w currently and you can see from the file that he averaged 338w which is around 90% of his FTP and 4.8w/kg for the duration of the 59min it took Greg to complete the 41km course.

Thank you for reading 5 articles in the past 30 days*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read any 5 articles for free in each 30-day period, this automatically resets

After your trial you will be billed £4.99 $7.99 €5.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just £49 $79 €59

Try your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

'I want it a lot more' - Kim Le Court puts Mauritius on the map

Victory drought over, now does the procession begin? Vollering takes control at La Vuelta Femenina

‘It depends on what Pogačar wants to do’ – Oropa summit finish on stage 2 will shake Giro d’Italia

Most Popular

Marcel Kittel reveals the power numbers and effort behind his most successful Tour de France years

The retired German sprinted has allowed his data to be studied to offer an insight into the demands of the Tour de France

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

Marcel Kittel has revealed some of the staggering power numbers behind his most successful Tour de France years in a new study.

The German sprinting star, who retired from professional cycling in 2019, has made his power data and other details available to researchers who have analysed his effort in four editions of the Tour de France.

A new research paper , titled ‘Demands of the Tour de France: A Case Study of a World-Class Sprinter (Part 1)', delves into the physical toll the Tour takes on a sprinter like Kittel and how the rider paced his efforts on different types of stage.

Kittel, posting on social media about the paper, said: “After I retired I was approached by Teun van Erp and he asked me if I would be interested to be part of a study to look into the demands of a Tour de France for a sprinter.

“Together with Rob Lamberts, he analysed my power data and sprints from 2013, 2014, 2016 and 2017. This week the study was published and I wanted to share my insights with you.”

The paper, written by Kittel, Teun van Erp and Robert Lamberts and published in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, covers the 2013, 2014, 2016 and 2017 Tours de France, in which Kittel won 14 stages in total.

Kittel weighed between 90kg and his lightest race weight 88.5kg (in the 2016 Tour), which the researchers used to calculate his Tour de France Functional Threshold Power (FTP) in watts per kilogram for each of the races.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

His highest FTP was in the 2016 and 2017 Tours, in which Kittel pushed 431 watts (4.9w/kg) and 438w (4.9w/kg) respectively.

The paper says that Kittel had a relatively low FTP in w/kg compared to other riders, but it was due to his enormous maximum power outputs that he was still able to succeed.

Kittel revealed that his highest ever power was 1,940w for three seconds during a training ride, but that his max power was slightly lower at the end of a race.

He also said that he needed to maintain that his weight in order to perform, saying: “My strength was my sprint and I needed the muscles (and weight) for it.

“If I would have lost five kilograms I would have still been one of the heaviest in the peloton, but maybe not the fastest anymore.”

The researchers said: “The sprinter, although highly successful in the sprint stages, finished in the last five per cent of the general classification. This position highlights the difficulty posed by the TdF for a world-class sprinter. To a certain extent, the low overall GC position could be attributed to tactics and taking it easy on certain stages as the overall GC position is not that important.”

“Although this world-class sprinter has a lower relative FTP than previously reported in professional road cycling, he was still highly successful, with 14 stage wins. His success lies in his unique capacity to produce extremely high explosive power outputs. To our knowledge, these are the highest values ever reported for a sprinter in a road race and, as such, are similar to power outputs reported in track cycling.”

The research also compared data from each of the four Tour de France editions, revealing the average stage length was between 159km (in 2013) and 176km (in 2017).

Kittel’s average power for each stage ranged between 256w (2.88w/kg) in 2017 and 264 (3.02w/kg) in 2016.

>>> ‘If I have to live with an unfair system, I don’t know if I want to continue’: Androni boss vents his anger after being left out of Giro d’Italia

In the conclusion, the researchers said: “Due to a lower relative FTP when compared with professional cyclists who specialise in other race types, finishing a Grand Tour is extremely strenuous for a world-class sprinter. A sprinter’s average daily load is around 10 per cent higher, and he will spend five per cent to 10 per cent more time in the high-intensity zones compared with a GC contender in a GT. The mountain stages pose higher demands when compared with the other mass-start race types. In addition, mountain passes situated in the beginning are executed with a high intensity to avoid the risk of becoming isolated.”

Part two of the study will look specifically at the sprints and the tactics in the final of a Tour de France stage.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Alex Ballinger is editor of BikeBiz magazine, the leading publication for the UK cycle industry, and is the former digital news editor for CyclingWeekly.com. After gaining experience in local newsrooms, national newspapers and in digital journalism, Alex found his calling in cycling, first as a reporter, then as news editor responsible for Cycling Weekly's online news output, and now as the editor of BikeBiz. Since pro cycling first captured his heart during the 2010 Tour de France (specifically the Contador-Schleck battle) Alex covered three Tours de France, multiple editions of the Tour of Britain, and the World Championships, while both writing and video presenting for Cycling Weekly. He also specialises in fitness writing, often throwing himself into the deep end to help readers improve their own power numbers. Away from the desk, Alex can be found racing time trials, riding BMX and mountain bikes, or exploring off-road on his gravel bike. He’s also an avid gamer, and can usually be found buried in an eclectic selection of books.

British rider remembers his victory at Paris-Roubaix juniors

By Tom Thewlis Published 4 May 24

Alfonsina Strada made headlines when she entered the 1924 edition of the Giro d’Italia, under the name 'Alfonsin', and the story of her grit and determination to finish against all odds lives on today

By Giles Belbin Published 4 May 24

The 14 time Tour de France stage winner backs Manxman to grab record breaking 35th stage win in the coming days

By Tom Thewlis Published 7 July 23

The German sprinter similarly took a break from cycling in May 2019, retiring a few months later

By Jonny Long Published 24 January 21

Sprinting icon Marcel Kittel reveals the reasons behind his retirement – and why cycling needs to open up about the extreme pressures endured by riders

By Chris Marshall-Bell Published 12 December 20

The German quit racing in 2019 while Dumoulin transferred to Jumbo-Visma after injury curtailed his season

By Jonny Long Published 18 November 19

The German sprinter has opened up about what his future holds

By Jonny Long Published 2 November 19

Marcel Kittel has shared more of his motivation for retiring from pro racing at 31.

By Alex Ballinger Published 31 October 19

The German said "[I] didn't want to watch my son grow up via Skype"

By Jonny Long Published 23 August 19

Riders give their views on how Tour de France sprints change without two of the race's best ever sprinters

By Gregor Brown Published 15 July 19

Useful links

- Tour de France

- Giro d'Italia

- Vuelta a España

Buyer's Guides

- Best road bikes

- Best gravel bikes

- Best smart turbo trainers

- Best cycling computers

- Editor's Choice

- Bike Reviews

- Component Reviews

- Clothing Reviews

- Contact Future's experts

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Advertise with us

Cycling Weekly is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site . © Future Publishing Limited Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA. All rights reserved. England and Wales company registration number 2008885.

- off.road.cc

- Dealclincher

- Fantasy Cycling

Support road.cc

Like this site? Help us to make it better.

- Sportive and endurance bikes

- Gravel and adventure bikes

- Urban and hybrid bikes

- Touring bikes

- Cyclocross bikes

- Electric bikes

- Folding bikes

- Fixed & singlespeed bikes

- Children's bikes

- Time trial bikes

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Child seats

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Arm & leg warmers

- Base layers

- Gloves - full finger

- Gloves - mitts

- Jerseys - casual

- Jerseys - long sleeve

- Jerseys - short sleeve

- Shorts & 3/4s

- Tights & longs

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Gear levers & shifters

- Handlebars & extensions

- Inner tubes

- Quick releases & skewers

- Energy & recovery bars

- Energy & recovery drinks

- Energy & recovery gels

- Heart rate monitors

- Hydration products

- Hydration systems

- Indoor trainers

- Power measurement

- Skincare & embrocation

- Training - misc

- Cleaning products

- Lubrication

- Tools - multitools

- Tools - Portable

- Tools - workshop

- Books, Maps & DVDs

- Camping and outdoor equipment

- Gifts & misc

How powerful is a Tour de France rider?

There has been a lot of talk in this year’s Tour de France about Chris Froome’s power data and its acquisition, but other riders have willingly published their own data from this year’s race, including Cofidis’ Daniel Navarro.

SRM provides the power measurement for more pro cycling teams than any other brand and it sometimes posts riders’ power graphs online during big races.

Well, Navarro’s average power over the entire stage was 247 watts (no, the graph isn't easy to read; you'll have to take our word for it).

If you use a power meter regularly you’ll often see figures higher than that, but you need to bear a couple of things in mind. First, Navarro was riding for over 6hrs. Second, he weighs 60kg (132lb, or 9st 6lb), and that’s a hugely important factor, especially on a mountain stage.

Those figures means he produced well over 4 watts per kg over the whole of the stage. And that was only good enough to get him 63rd place!

At the start of the Col de la Core, Navarro actually produced an average of 371 watts over 4mins (graph below, the green line is power but, again, you'll have to trust us on the figures). That’s 6.18 watts per kg halfway into a 6hr ride.

So, now you can work out what sort of wattage you need to produce for your bodyweight in order to get yourself a mid-level finish. Better slide that cake to one side and get training, then!

For more info go to www.srm.de .

Help us to fund our site

We’ve noticed you’re using an ad blocker. If you like road.cc, but you don’t like ads, please consider subscribing to the site to support us directly. As a subscriber you can read road.cc ad-free, from as little as £1.99.

If you don’t want to subscribe, please turn your ad blocker off. The revenue from adverts helps to fund our site.

Help us to bring you the best cycling content

If you’ve enjoyed this article, then please consider subscribing to road.cc from as little as £1.99. Our mission is to bring you all the news that’s relevant to you as a cyclist, independent reviews, impartial buying advice and more. Your subscription will help us to do more.

Mat has been in cycling media since 1996, on titles including BikeRadar, Total Bike, Total Mountain Bike, What Mountain Bike and Mountain Biking UK, and he has been editor of 220 Triathlon and Cycling Plus. Mat has been road.cc technical editor for over a decade, testing bikes, fettling the latest kit, and trying out the most up-to-the-minute clothing. He has won his category in Ironman UK 70.3 and finished on the podium in both marathons he has run. Mat is a Cambridge graduate who did a post-grad in magazine journalism, and he is a winner of the Cycling Media Award for Specialist Online Writer. Now over 50, he's riding road and gravel bikes most days for fun and fitness rather than training for competitions.

Add new comment

10 comments.

He didn't limit his complaint to just sport... It sounds like he'd have none of us competing over anything..:

- Log in or register to post comments

Quote: One human comparing itself with another is completely pointless

So all competitive sport is pointless?

crikey wrote: Quote: One human comparing itself with another is completely pointless

Looks like it.

To be fair, a lot of top sports people and teams (including Sky) operate to a philosophy of doing everything that you can do to the absolute best of your ability, stick to the plan, don't worry what others are doing.

A bit like when there's an attack on a mountain and Sky don't seem to react but instead keep churning the steady watts that eventually pulls them back to the attacker and past - so you're right, it kills sport as a competition, haha!

One human comparing itself with another is completely pointless. Just do all you can, thats all you can do.

Beaufort wrote: One human comparing itself with another is completely pointless. Just do all you can, thats all you can do.

Watts/Kg is a good compare tool. It caters for all shapes and sizes. Being a bigger guy I have loads of power, then factor weight and my results are mediocre compared to good club or pro cyclist. You can then hopefully appreciate the work needed to become a top rider.

As he's 4.5 stone lighter than me and probably 17 years or so younger I aren't going to be troubling him either!

I have a local mate who rides with Madison Genesis and avoid him on rides as I don't want to waste his training time. I did travel back with him from a ride back in May. I'm no slouch on the chainy but I was hanging on for grim death while he was chatting away in front of me, riding in the little ring and moaning about just getting over his cold...

I could have been a contender! Hmmmm. Perhaps not.

CXR94Di2 wrote: I thought my 3.3w/kg over an hour was good

Latest Comments

And if you put the Gamel Helmet on back to front. You could become Robocop!

Bit dark...

On the other hand though ......

A group of Engineering professors were invited to fly in a plane. Right after they were comfortably seated, they were informed the plane was built...

Yeah, this whole thing can really just get to fuck. But that's what we're up against - the normalisation of the plucky chancer driver, the...

There are times when I think that these right whinger accounts are left wingers in drag, the aguments they espouse are so ridiculous, or don't...

Or any non-drivist. A few years back, I was walking and crossing a side road not far from home. The road has particularly wide corners, especially...

This was it in November 2022. Now you see the futility of reporting things to the police or DVLA

I'm trying to login at my mobile and it says I need to subscreve. What should I do?

I can tell you exactly what LC will be doing about that offence: nothing. I used to get letters like those- in fact, exactly like that. When you...

Most Popular News

- Training and Health

- How To…

- Live Streaming

You versus a Tour de France cyclist: Why power measurement is important?

Power is the rate at which energy is used (energy over time) and is measured in watts.

In cycling, energy is expressed in terms of work. It’s a constant snapshot of your work rate at any given moment. It’s the building block from which all power-based training flows.

A watt is a watt, whether on a bike or powering your home. So when Marcel Kittel unleashes 1,900 watts in a sprint, he could essentially power two houses at normal consumption level. Another comparison: 1 horsepower is 746 watts.

For decades, cyclists measured their performance by looking at miles per hour or heart rate. In the 1990s, elite cyclists switched to measuring their power output in watts. Since the late 1980s, companies including SRM, Powertap and Ergomo have made these devices, which measure the deflection of the crank arm using minuscule gauges or in some cases employ a specialized wheel hub.

A handlebar computer displays and stores the data. Whereas an average cyclist can produce 100 watts, a pro cyclist can average 400 watts over the final hour of a Tour de France stage.

Training intensity is the toughest variable to measure. Speed is a poor measure, as it relates more to terrain and wind. Heart rates provide a rough gauge, but they vary in response to temperature, humidity, altitude, hydration, fatigue, caffeine intake and exercise duration.

Energy delivered to the pedals and measured in watts measures the intensity of your work. Measuring power allows you to monitor your training, characterize your practice course, assess your aerodynamic sleekness and drag, and assist in pacing.

Wattage figures measure the work of applying energy to the pedals but not the total physiological energy expended to perform the task. Cyclists are about 21 to 24 percent efficient in converting chemical energy to mechanical energy during cycling, so a cyclist riding at 250 watts is expending metabolic energy at a rate of nearly 1,000 watts, or 1 horsepower.

The advantage of power monitoring is that “watts don’t lie,” writes Selene Yeager in “Every Woman’s Guide to Cycling.” Wattage figures stay exact, unlike heart rate. If you ride your standard circuit and average 160 watts where before you only managed 125, you have gotten stronger, she indicates.

To measure your wattage, you warm up and ride for 20 minutes at the highest power you can maintain. You reduce that number by 5 percent to arrive at your lactate threshold power, which is the wattage you can maintain for about an hour. With your coach, you then set up training zones of varying duration and watts.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Cyclists live longer, a new study suggests

What you need to know about calories as a cyclist

Lower back pain on the bike – what should you do?

Mathieu van der Poel’s insane Strade Bianche power data revealed

Vitamin and mineral supplements could do more harm than good, says new study

3 training rides to do every week if you want to be faster

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

EDITOR PICKS

2024 Giro d’Italia LIVE STREAM

2024 Vuelta Espana Femenina LIVE STREAM

2024 Famenne Ardenne Classic LIVE STREAM

Popular posts.

Giro d’Italia, Milan-San Remo under threat of cancellation due to coronavirus

2020 UAE Tour LIVE STREAM

Ewan storms to victory on stage 2 of UAE Tour

Popular category.

- Results 1805

- Grand Tours 1567

- Tour de France 707

- POPULAR THIS WEEK 616

- Live Streaming 575

- Giro d'Italia 548

- Interviews 382

One Month Free Trial

How Hard are the Tour de France Stages for Cyclists?

By Jeremy Powers

We break down the difficulty of various Tour de France stages as riders take on the mountains, flat sections and time trials, using WHOOP data and other metrics.

The Tour de France is widely considered one of the most grueling and difficult athletic events on the planet. For 21 stages spanning 23 days, cyclists push their bodies to the max--day, after day, after day, after day. How hard are the various individual stages? We wanted to take a look at data we’ve been able to capture over the years from the big stages of the Tour de France, as well as the Giro d’Italia, another Grand Tour stage race that is three weeks long. We can use this data to better understand the incredible effort that these riders will undertake at this year’s Tour de France.

The Strain and Exertion of Tour de France Stages

Generally speaking, a "normal" day at the Tour has a rider putting out somewhere around 230-250 watts on average (think of this as pressure on the pedals), which equates to about 900 kilojoules (a fancy way to say calories) per hour. Multiply that by 5 hours and it’s almost 5000 calories! And more often than not, this equates to a WHOOP strain score above 20 (strain is how we measure cardiovascular exertion, on a scale of 0-21). On some of the harder stages, this is closer to 300+ watts and 1100 calories/KJ per hour. Even for the fittest athletes in the world, this is a wild number and gets your cardiovascular system really fatigued. Strains over 20.5 are not uncommon.

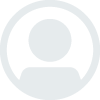

Daily WHOOP Strain Data from Each of Last Year’s Tour de France Stages

This graphic shows the average strain (in blue) for members of the EF Education - NIPPO Pro Cycling Team during each stage of the 2020 Tour de France:

The average daily WHOOP strain and recovery for EF riders DURING THE 2020 TOUR DE FRANCE.

Below we’ll take a look at some of this year’s Tour de France stages (a mountain stage, a flat stage and a time trial) and break them down based on data we have from previous races.

Mountain Stage & High Strain

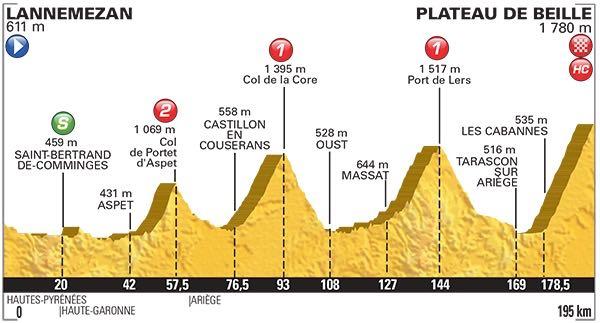

Stage 8 of this year's Tour de France is the first true mountain stage: Distance: 94 miles (151 kilometers) Elevation: 11,000 feet of climbing ETA to Finish Stage: 5 hours, depending on weather, heat, etc.

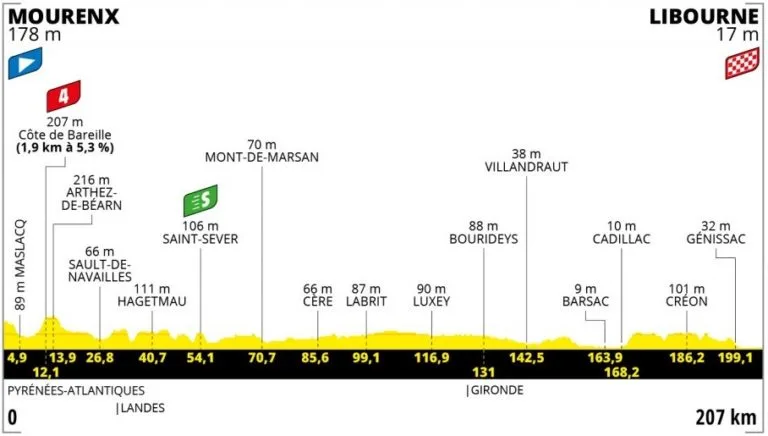

The layout of Stage 8 in the 2021 Tour de France.

If we look at the last time we visited this stage, we actually have data from Lawson Craddock in 2018 . Back then, it was Stage 10 of the 2018 Tour de France. To give you a sense of things during that moment, at the time Lawson said this to us: “It was a rough day for me. I felt better than expected on the first climb, but that feeling was short lived. I suffered over the second mountain pass, but once we hit Col de Romme I was cooked.” Lawson had a solid 70% WHOOP recovery that day with a 20.6 strain, his most strenuous stage of the Tour to that point. His average heart rate for the ride was 146 beats per minute, his max heart rate was 183 bpm (near his top) and he burned around 4,600 calories/KJ. To use another example, Stage 6 of this year’s Giro d’Italia was also a very similar alpine stage--100 miles, roughly 5 hours of riding and 11,200 feet of climbing. Here’s a glimpse at some of EF rider Simon Carr ’s metrics from that stage: Recovery: 25% Day Strain: 20.5 Average HR: 145 bpm (nearly identical to Lawson’s mentioned above) The Giro’s Stage 6 had comparable terrain, mileage and elevation to Stage 10 of the 2018 Tour de France, and to what we’ll see in Stage 8 of the Tour this year. On these big climbing days there is no hiding. We can almost certainly expect the riders hitting strains of 20.6 and higher, and hopefully they’re waking up in the green ready to take on this massive day. But with it being the 8th straight day of competition, following a hectic first week and no rest days yet, chances are this is going to be a stage of attrition. Napping , blue light glasses, nutrition, hydration , massage, focussing on sleep consistency … literally every recovery method in the book is what the riders will be striving for leading into and after a huge stage like this.

Flat Stage & Max Heart Rate at the Finish

Stage 19 of this year’s Tour fits this billing: Distance: 129 miles (207 kilometers) Elevation: 4,120 feet of climbing ETA to Finish Stage: 5 hours and should end in a sprint

THE LAYOUT OF STAGE 19 IN THE 2021 TOUR DE FRANCE.

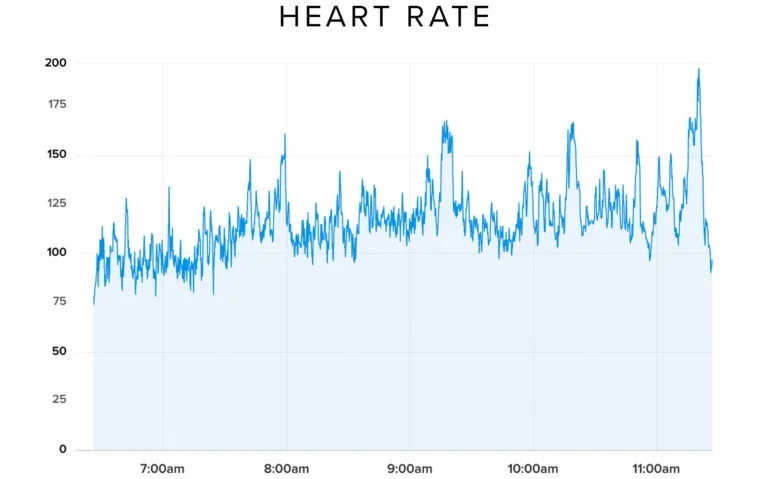

Now that we’ve seen what a day in the mountains looks like, let's crunch a little data from some flat stages. These stages of a Grand Tour tend to be “easier” relative to what the riders are doing on the hillier days. Here’s a snippet of what we wrote during the 2018 Tour: “Lawson completed Stage 07 today, spending more than six hours on the bike. It was a long, mostly flat stage referred to as ‘boring’ by a few riders.” This is less true on days when certain riders have to “ride in the front” for the team’s sprinter or “get in the breakaway,” so let’s exclude those and just focus on a typical flat stage from someone who’s “sitting in the bunch.” At the Giro this year, the 13th stage was 126 miles long and flat as a pan. Simon Carr only burned 2700 calories/KJ with a WHOOP day strain of 15.9. This is an atypical stage of a Grand Tour, but it highlights just how different each day can be. Also, towards the end of these flatter stages it’s often very chaotic and dangerous as they come into the finish line, and it gets going fast . Looking at Simon’s heart rate data from this stage, you can see that he is full gas in the last 30-45 minutes and maxed out his HR just to finish in the pack.

Simon Carr's heart rate during the flat Stage 13 of the 2021 Giro d'italia.

Time trial stage & non-stop elevated hr.

Stage 5 of the Tour this year is a time trial: Distance: 17 miles (27 kilometers) Elevation: 1089 feet of climbing ETA to Finish Stage: 30 minutes

THE LAYOUT OF STAGE 5 IN THE 2021 TOUR DE FRANCE.

Time trials are dubbed “the race against the clock,” which is a short (usually under 60 minutes) but constantly hard individual effort. The strain we see is different from any other days of a Grand Tour. If the riders pace it right, their heart rates will be lower at the beginning and progressively go up and up to the finish line. When you factor in what they do to warm up and cool down it can still end up being a “big day”--especially considering riders often need to finish within a certain time percentage of the winner in order to stay in the race. They can’t go out there and lallygag even for a moment, they have to keep moving even if they're not in the hunt for the overall or stage win. Lawson completed Stage 20 of the 2018 Tour (a 31-mile time trial) in just under 48 minutes, and his day strain still topped 16. Similarly, Simon hit a strain of 16.6 at the Giro’s Stage 21 time trial this year, despite being on the bike for only 18+ miles and 36 minutes. However, he spent 33 of those 36 minutes at 80% or more of his max heart rate, with his HR rarely dipping below 160 bpm the entire time. RELATED: Pro Cyclist Heart Rate, Strain & Tour de France Data

How to Analyze a Tour de France Power File

TrainingPeaks co-founder and power expert Dirk Friel shares the secrets of how he analyzes a Tour de France power file.

It wasn’t long ago that race fans didn’t have any insight into what the data of professional cyclists in the Tour de France looked like. As a major cycling fan and data geek myself, I always wondered what kind of numbers the Tour riders were putting out. Today, through the efforts of power meters and software companies like TrainingPeaks, we have a very clear picture of what it takes to compete in the world’s biggest bike race.

At TrainingPeaks, we have been longtime advocates for making cycling more transparent, but many of the riders themselves are also starting to question why race data has been held so secretive for so for long. Several riders in the peloton have taken it upon themselves to freely share their race data, sometimes within minutes of crossing the finish line.

Race analysis is also starting to evolve as cycling fans become more sophisticated and knowledgeable about how to watch bike races. To the inexperienced eye, cycling may look like a boring or confusing sport, but to the avid fan, it’s a chess match on wheels with endless variables that can disrupt the best of strategies—or the strongest of riders.

How Power Data Helps to Tell the Story

Race data can give us an inside view into the results as well as foreshadow the next day’s events. The numbers give depth to the story and can reveal the reasons a team’s plans were disrupted. This shows up as peak power values set early in the stage, which creates a dark and dismal final hour of racing. Likewise, a power file can reveal a hero, such as when a teammate comes to the rescue and takes on the workload to help their leader save energy for the finishing climb. What did it take for our hero to save the day? Was it their hardest effort of the race? Could they have gone even harder? These are questions and answers that can only be revealed through the numbers.

I liken race data and the ability it gives us to create richer post-race analysis to the kind of game day coverage we’ve become accustomed to within the big three American sports: football, basketball and baseball. These sports track stats and dive into the numbers during and after each game. Halftime is a time to analyze the stats of the star players and make second-half predictions. Post-game shows summarize the stats and reveal an extra layer that wasn’t evident during the game itself. What was the quarterback rating? Who had the most assists?

As you come across race-day files from the pros during this year’s Tour de France, you can do your own analysis as if you were the expert cycling commentator. Take a look at the stats and see what conclusions you come to. There’s no exact science when it comes to analyzing power files, but here are a few things I’ve picked up over the years that may help you make sense of this year’s power data from the Tour.

TSS ® and IF ®

Duration and the Training Stress Score ® (TSS ® ) of the race is one of the first things I look at. This helps me determine how hard the race was. 100 TSS denotes an all-out, 100 percent effort for 60 minutes. As a rule of thumb, you can’t accumulate more than 100 TSS points an hour. TSS also tells me a little about the rider’s Functional Threshold Power (FTP) settings.

The TSS accumulated within the stage can show how hard it will be to recover from the day. As a general rule, Joe Friel calls 150 TSS the threshold for a “hard workout.” Anything over 300 TSS will be tough to recover from and certainly be felt for days to come. You can also look at the Intensity Factor ® (IF ® ) of the race to determine how intense this athlete’s effort was the day, relative to their FTP. A very hard race will have an Intensity Factor of .75 or higher.

One great example of a 300+ TSS day and a race that produced an IF of higher than .75 is former Tinkoff rider Michael Rogers’ stage 16 victory at the 2014 Tour. His amazing effort brought him a big win on a very tough day in the saddle.

Peak 20-minute Power

By taking a quick look at the rider’s Peak 20-minute Power value of the day, you can get a sense of how intense the rider raced. We choose 20 minutes because riders rarely ever race 100 percent for 60 minutes, but they do race at 95 to 100 percent for 20 minutes on climbs. So you can get a good indication of FTP by looking at their peak 20-minute power output.

For their peak 20-minutes, I look at both their watts and watts/kg, a measure of their power to weight ratio. Don’t get fooled into looking at the absolute watts value, as two riders may produce the same watts but that may mean dramatically different watts per kilogram (w/kg). Your w/kg determines your speed as all else being equal, the higher the watts or the lower the weight, the faster the rider will go.

A quick look at peak 20-minute watts/kg can tell you how hard the rider went on the climbs. Quite a few top climbers in the Tour de France can ride right at or slightly above 6.0w/kg for 20 minutes. If their peak 20 minutes was less than 5.5 w/kg, they were well within their limit.

Power Trends

How does the power trend look within the file? This can tell you if the rider raced hard in the first half of the race (maybe trying to get into a breakaway) or in the last quarter of the race. On the big, important stages the team leaders will ramp up their intensity so they are going harder at the end than they are at the beginning in an effort to stay with, or get away from their rivals. Riders going for a stage victory or who help protect their team leaders tend to put out their max power values in the first half of the stage and then just ride to get to the finish line. This can be different on sprint days, where max values for almost everyone are found near the end as the peloton stays together for the sprint finish and the average speeds ramp up at the end with attacks.

For a time trial, I usually start by comparing average and Normalized Power ® (NP ® ) for the first versus the second half. I may also do this sometimes for long, key climbs. I also look for segments with obvious surges or “burnt matches” (significant efforts over threshold) that could denote attacks from the peloton or a rider trying to make a break.

The Role of the Rider

The role the rider plays within the team determines a lot when it comes to analyzing the data. I take a look at when Peak Power values occur in the file to see when the rider was working hardest. As mentioned earlier, a team leader will tend to put out higher power values near the end of the stage as they race for precious seconds, while team domestiques (helpers) may put out their peak power values well before the finish line in an effort to help their team leaders.

When you see a domestique cranking out over 10 w/kg to lead out their team leader for a potential win, and then see the power drop as they “pull the plug” and roll into the finish once their job is done, it really becomes apparent just how much of a team sport cycling is. An example of this can be seen in Lotto-Belisol rider Greg Henderson’s file from Stage 4 of the 2012 Tour, when he cranked out 9.5 w/kg in the final minute to bring Andre Greipel across the line for the win.

Flat tires and bad luck can also sometimes be viewed within a file as a rider may have to chase back on after a crash or a flat. Instances like these can zap their energy and can cause time loss near the end if a chase created too much fatigue.

Variability Index

Variability Index (VI) is primarily a metric you may want to take a look at when analyzing time trials. Variability Index indicates how smooth the rider paced their effort. The more evenly they produced power, the closer to 1.0 their VI will be. This is very evident in uphill time trials where there isn’t a lot of variation between the peak power outputs and the average watts. In fact, the formula for calculating VI is simply NP divided by average power. NP is an estimate of the power you could’ve maintained for the same physiological “cost” if your power output had been perfectly constant, and it provides a better measure of the true physiological demands of an effort by taking into account any power surges.

You will see a higher VI if a time trial is flat and has a lot of corners which demands a lot of power spikes as the rider negotiates turns and powers back up to speed. In general, the lower the VI the better job the rider has done in pacing their time trial. However, a team time trial would invariably have a large VI since the riders are taking turns on the front where they have huge power spikes alternated by lower power values when sitting in the draft.

Now it’s Your Turn

Just as every stage in the Tour will be different, no two power analyses are the same, and different people can look at the same file and see different points to highlight. This is just a quick primer on some of the numbers I typically look at, but it should provide a basis for starting to look at pro power files and drawing your own interesting observations about “the story of the day.”

Ultimate Century Training Guide

Training Guide

This guide is designed to be used as you train for a century, with in-depth information on every part of the process. Each chapter is packed with tips, workouts, and insights from expert cycling coaches, to give you all the tools you need to succeed.

Dirk Friel is co-founder and Chief Evangelist of TrainingPeaks and Peaksware. Dirk has been helping age-group athletes, Olympians and World Champions track, analyze and plan their training for more than 20 years.

Your cart is empty

How fit are Tour de France riders?

What does it really take to race, finish, and even win the world's toughest endurance sport event?

Words: Nick Busca

Photos: Getty Images

To cycle 3,328 km in 21 days (with only two days of rest), you need to be incredibly fit. What's more, you need to be even fitter to cycle that length at an average speed of 40kph. And to survive the 48,859 metres of vertical elevation spread along the course, you must be in the best shape of your life.

But how fit do professional riders need to be if they want to ride the Grande Boucle and finish it, let alone win it?

Have they done it before?

"The first, most obvious step is knowing if a rider can race a three-week stage race because that's quite a unique physical demand, and they need to get through that in a good way," explains Dajo Sanders, sport scientist and coach for the DSM pro cycling team.

Related: How fast is the Tour de France?

If a rider has already completed a Grand Tour or a shorter stage race, that is a suitable starting parameter. But what about other riders who have not completed one yet? And what is the demand, in general?

Aerobic powerhouse

But then, within the peloton, we know there are different types of riders: GC contenders, breakaway specialists, time triallists, and sprinters. Do they all need to match the same requirements? Yes and no.

Related: One kilo a day. What riders eat on hard, Alpine stages at the Giro

"We look at a multitude of metrics, but how we interpret those numbers depends a lot on what their main role is," explains Sanders.

And, also very importantly, all types of riders need to produce their best power outputs in a race scenario because it's pretty different to do it when they're fresh and when there's the onset of fatigue. As Sanders and other researchers showed last year with this study , what separates the best riders from the rest of the peloton is the ability to maintain a high power output after accumulating high workloads.

Different physiology, different metrics

In training, if a rider has not completed a Grand Tour, or if they have and are still fighting for the spot in the team, Sanders and his colleagues look at several metrics. For example, for sprinters, they look at their ability to perform well aerobically for several hours, but also at their max 10-15 sec power output at the end of long training rides.

Related: The hardest climbs of the Tour de France

But to win a Tour de France, a rider needs to be complete and perform well in time trials, too. "To have this information we look at the power they're able to produce for long durations in relation to their aerodynamic drag," explains Sanders.

The data and numbers

Although being chosen is a process that takes into account the practical knowledge of the rider and their specialisation, there is certainly a lot of data analysis behind the selection of Tour de France riders, too.

Related: High-tech training and racing. A round up of the best software for metabolic testing

"A basic but good first gauge to get an idea about someone's ability to tolerate a high workload, like within a Grand Tour, is their annual training volume - the number of hours they have trained in a year and for several years," he says. And that's why coaches are quite cautious of launching juniors into a Grand Tour.

Related: What is FTP and how can you improve it?

"We also look at individuals' fresh power profile, their ability to produce power across various durations, and the profile after previously accumulating workload," he says. "Then we add these to the training hours and have a good idea if someone's ready to be competitive within a GT."

VO2max and thresholds

Although it's hard to determine whether someone is fit for a GT from a VO2max value or lactate threshold alone, Sanders still points out a range of values he has seen over the years in his career, which has been reported in the scientific literature too.

"There's a study on Chris Froome showing a relative VO2max of 84 millilitres per kilogram per minute, or 5.9 litres per minute absolute," he says. "And there's another study on Tour de France riders, showing them ranging between 79 and 86. A study that came out last week showed that top-five Giro riders had VO2max ranging between 80 and 82. So from that perspective, the suggestion is that if you want to win the Tour de France, you need to have a VO2max of a minimum of 80 millilitres per kilogram per minute."

Related: What is VO2max, why is it important and how can you improve it?

It is a little more challenging to talk about watts per kilo, as riders tend to obsess about this metric, which can lead to other issues or question marks around some performances. Plus, metrics are always contextual, as heat, fatigue, and freshness can drastically change these values.

Related: Recover and race smart. High Carty on how to beat fatigue in a Grand Tour

Once again, though, previous studies can give a better overview – although still a limited one. In this case, it was a study on Tom Dumoulin's best years as a GT contender .

Related: Tour de France 2022, stages and route

Finally, calculating power outputs from other values without having the actual power profile would be a massive generalisation and would not provide enough context for a rider's performance.

Team Cars | Service Des Courses - Organic Unisex T-shirt

Rouleur Team Cars Bone China Mugs

Rouleur ELITE Jet Water Bottle Bidon - 550ml

Rouleur Logo Organic Unisex T-Shirt - Black/White

Team Cars | Campagnolo - Organic Cotton Unisex T-Shirt

Rouleur Logo Organic Unisex T-Shirt – White

Rouleur Logo - Organic Sweatshirt - Unisex - Burgundy

Team Cars | Peugeot - Organic Cotton Unisex T-Shirt

Colours of the Peloton - Short Sleeve Base Layer - Men's

Rouleur Logo Organic Unisex T-Shirt – Tonal Grey

Team Cars | Raleigh - Organic Cotton Unisex T-Shirt

Rouleur Logo Organic Sweatshirt - Unisex - Grey

Coppi - Rouleur Notebook

Rouleur Logo - Organic Sweatshirt - Unisex - French Navy

Rouleur Logo - Organic Hooded Sweatshirt - Unisex - Heather Blue

Rouleur Logo - Organic Jogger Pants - Unisex - French Navy

Rouleur x Kaweco Rollerball Pen - Black + Gold foil logo

Allez - Organic Cotton Unisex T-Shirt

Tours Issue - Rouleur Tote Bag

Dai! - Organic Cotton Unisex T-Shirt

True Grit - Rouleur Notebook

Rouleur Water Bottle Bidon - Ride Fast, Read Slow - Cream + Green

Rouleur Water Bottle Bidon - Green + Pink

Rouleur x Kaweco Rollerball Pen - Brass + Black etched logo

Rouleur Embroidered Organic Cotton Unisex T-Shirt - Natural Cotton + Green

!Vamos! - Organic Cotton Unisex T-Shirt

Colours of the Peloton - Short Sleeve Jersey - Women's

Rouleur Logo Women's T-Shirt - Navy

Rouleur x Kaweco Aluminium Rollerball Pen - Silver + Engraved logo

Rouleur Logo - Organic Jogger Pants - Unisex - Heather Grey

CURRENT PRICES END MAY 12

Outside Festival feat. Thundercat and Fleet Foxes.

FROM JUST $44

How Much Energy Do Tour de France Riders Produce?

Enough to power the Eiffel Tower for three days or run a home on solar for 27,000 hours, to start

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

With the GC race at the Tour de France stalled out beneath Team Sky’s interminable grind, the folks over at Exercisebike.net apparently got as bored as we have and started doing some back-of-the-napkin noodling. Basically, they wondered, with 198 riders covering 2,187 course miles over three weeks, how much energy are they producing? And what could you do with all of that power? The answers provide some fun factoids. They also make us think that there should be some way to hook up our trainers and start harnessing all that output to power our daily lives. You can see all the findings here , but these are the numbers that surprised us most.

Clean Energy

Perhaps the most compelling stat is how the energy generated by all the Tour riders collectively stacks up to other fuel sources. Collectively, the energy generated by the racers over the course of the tour is about the same as that of 5,300 pounds of coal, 371 gallons of gasoline, 51,500 cubic feet of natural gas, or almost 27,000 hours of solar power production. Backing that out, that means that a single rider produces the equivalent of 1.87 gallons or 136 hours of solar power.

Energy Hogs

The study speaks to how energy hungry we are as Americans. Tour power could run the average French home for 663 days, or nearly two years, but an American one for just 170 days. Similarly, while the output from Tour races could run the Eiffel Tower, which is lit by 20,000 six-watt bulbs, for over three days, it would only keep the lights on at the Empire State Building for around 50 minutes. Guess we’ll have to get more Americans riding.

Food for Thought

On a more banal level, the study equates the output of a single rider over the three weeks of the Tour to normal household appliance usage. The average Tour racer could light a 100-watt bulb for 257 hours, run a washing machine for 52 hours, or grill toast in a toaster for 32 hours. The same amount of energy would run a hair-dryer for just 13 hours, though presumably it would be easier to fluff that coif with just a few minutes in the saddle.

Exercisebike.net says that the energy generated by the Tour racers would be enough to power a Tesla road trip across the U.S. some 6.5 times. That sounds like a lot, but it’s probably only a quarter of that—just 1.5 coast-to-coast miles— based on average U.S. gas mileage. While we’re impressed with all the other stats, this one seems underwhelming given that it’s three weeks of energy from 200 riders for just a single, passenger car trip. It would be far more fuel efficient—and nearly as quick—to just pedal yourself across the country, as Lael Wilcox did recently on her 18-day winning cruise on the TransAm .

Popular on Outside Online

Enjoy coverage of racing, history, food, culture, travel, and tech with access to unlimited digital content from Outside Network's iconic brands.

Healthy Living

- Clean Eating

- Vegetarian Times

- Yoga Journal

- Fly Fishing Film Tour

- National Park Trips

- Warren Miller

- Fastest Known Time

- Trail Runner

- Women's Running

- Bicycle Retailer & Industry News

- FinisherPix

- Outside Events Cycling Series

- Outside Shop

© 2024 Outside Interactive, Inc

How Fast and Powerful Are Pro Women and How Do Your Stats Compare?

We break down some key performance metrics of the world’s best cyclists to see how we’d all stack up.

Gear-obsessed editors choose every product we review. We may earn commission if you buy from a link. How we test gear.

Time Trial Speed

Pro women’s teams crank out team time trials at around 30+ mph speeds. For example, Eva Buurman and the squad from Team TIBCO-Silicon Valley Bank averaged 31 mph (49.9 km/hr) during last year’s 2020 Giro Rosa team time trial (16.8 kilometers/10.4 miles).

In comparison, the winning women’s team at the 2019 Philly Phlyer, Mathletes Racing , finished in 22:24 and 29 mph average (11 miles). That’s still super fast, but once you get over about 18 to 20 mph, the power you need to overcome wind resistance increases exponentially . That’s where that pro-level power kicks in.

Average Heart Rate

Pro hearts can jackhammer along at super high rates, ranging from an average of 178 bpm for nearly four hours for Leah Dixon (Team TIBCO-Silicon Valley Bank) to an average of 186 bpm during the Giro Rosa last year for Eva Buurman.

But if you’re not hitting those numbers, don’t sweat it. A healthy threshold heart rate for a typical active woman is in the ballpark of 155 to 160 beats per minute, depending on your age.

Power-to-Weight Ratio

The power-to-weight ratio, or how many watts you can produce per kilogram or pound of body weight, is one of the hallmarks of cycling success, and world class women riders can generate enough to power a house . Pro women at the top of the ranks can produce about 19 W/kg for 5 seconds; 9 W/kg for 1 minute; 6.5 W/kg for 5 minutes; and 5.5 W/kg at their threshold, according to power guru Andrew Coggan, Ph.D ., co-author (along with Hunter Allen) and cycling scientist behind Training and Racing with a Power Meter .

Good amateurs, on the other hand, can generate about 13.5 W/kg for 5 seconds; 7 W/kg for 1 minute; 4.5 for 5 minutes; and about 3.7 W/kg at their threshold.

What does that wattage look like in real life? Well, in Gent-Wevelgem, Kristen Faulkner threw down:

- Average power: 226 watts

- Normalized power: 289 watts

- Max power: 1,005 watts

- 1-minute power: 463 watts

- 5-minute power: 383 watts

- 10-minute power: 338 watts

Training Hours Per Week

Being a pro is a full-time job (which many women do on top of their full time job…but that’s another story), and time on the bike alone is a part-time job. Pros like Sarah Gigante (TIBCO-Silicon Valley Bank) clock about 20 hours of riding time a week.

For serious recreational cyclists not paid to ride their bikes, half that amount—about 10 hours a week—is a solid amount of weekly training time. Bonus: 10 hours of riding a week also doubles the odds of aging disease-free and fully functional.

You can’t be a pro unless you’re fast. And the women in the front of the women’s pro peloton, like Chloé Dygert (Canyon/SRAM Racing) are consistently quite speedy. Dygert swept all four stages of the 2019 Colorado Classic, maintaining an average speed of about 23 mph for most of the 220-mile race.

To put that in context, fast amateur women tackling the same terrain at the Steamboat Stage Race in Colorado that same year averaged about 19 mph.

Resting Heart Rate

Pros are so efficient at using oxygen, their hearts don’t need to tick at very high speeds when they’re not nose in the wind. Dixon, for instance, has a resting heart rate of a leisurely 38 bpm. The average resting heart rates among the women of Canyon/SRAM Racing range from 35 to 60, says team performance director Lars Teutenberg.

Considerably higher resting heart rates of 60 to 100 bpm are considered normal, though fit women will often have heart rates at the lower end of that range.

Considered one of the gold standard metrics of endurance performance, VO2 max is the maximum amount of oxygen that your body can take in and use. (It’s recorded in milliliters per kilogram of weight per minute of exercise or ml/kg/min.) As you’d expect, pros can take in and use a lot. But it’s important to note that there’s not a direct relationship between a high VO2 max and podium-level performance. Many other variables, such as lactate threshold and efficiency (not to mention tactical smarts) are equally, if not more, valuable in the race for the top spots.

So it’s not terribly surprising that there’s “quite a bandwidth” in VO2 max—ranging from 69 to 80 ml/kg/min on the Canyon/SRAM team, according to Teutenberg. Though most of the riders fall into the 70 to 75 ml/kg/min range—a typical range for elite athletes.

VO2 max is trainable to a point. Other factors like genetics, body composition, and altitude are all at play. It also decreases with age. Generally speaking, a VO2 max of between about 31 and 37 is considered excellent for healthy adult women , and trained women will fall in the 55 to 60 ml/kg/min range.

FTP, or functional threshold power , is the average number of watts you can sustain in an hour and it’s a strong predictor of cycling success. On average, the women on Canyon/SRAM team fall into the 250 to 300 watt FTP range, says Teutenberg, which definitely puts them in rarified air.

Forty six percent of women riders using Cycling Analytics (generally serious recreational cyclists) have an FTP of below 200W, 44 percent have an FTP of 210W or more, and 10 percent have an FTP between 200W and 210W.

Bonus: Test Yourself!

Last year Team TIBCO-Silicon Valley Bank had Lauren Stephens do a max speed sprint effort on her trainer. She went from 0 to 50.9 kph/31.6mph in 30 seconds!

That’s one you can definitely try at home to see how you measure up. Good luck!

.css-1t6om3g:before{width:1.75rem;height:1.75rem;margin:0 0.625rem -0.125rem 0;content:'';display:inline-block;-webkit-background-size:1.25rem;background-size:1.25rem;background-color:#F8D811;color:#000;background-repeat:no-repeat;-webkit-background-position:center;background-position:center;}.loaded .css-1t6om3g:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/bicycling/static/images/chevron-design-element.c42d609.svg);} Training

Do You Really Need a Power Meter?

How Exactly to Do Bicycle Crunches

Strength Workouts to Help You Ride Faster

Cycling Tips for Older Riders

Your 4-Week Training Plan to Get Faster

Build a Strong Core With V-Ups

How to Improve Your Ankle Mobility

20-Minute Exercise Ball Workout

How to Calculate Your Power-To-Weight Ratio

The Best Exercises to Increase Mitochondria

How Often Should You Ride?

Tour de France: How many calories will the winner burn?

Professor of Physics, University of Lynchburg

Disclosure statement

John Eric Goff does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

Imagine you begin pedaling from the start of Stage 17 of this year’s Tour de France . First, you would bike approximately 70 miles (112 km) with a gradual increase in elevation of around 1,300 feet (400 m). But you’ve yet to hit the fun part: the Hautes-Pyrénées mountains. Over the next 40 miles (64 km) you would have to climb three mountain peaks with a net increase of a mile (1.6 km) in elevation . On the fittest day of my life, I might not even be able to finish Stage 17 – much less do it in anything remotely close to the five hours or so the winner will take to finish the ride. And Stage 17 is just one of 21 stages that must be completed in the 23 days of the tour.

I am a sports physicist , and I’ve modeled the Tour de France for nearly two decades using terrain data – like what I described for Stage 17 – and the laws of physics. But I still cannot fathom the physical capabilities needed to complete the world’s most famous bike race. Only an elite few humans are capable of completing a Tour de France stage in a time that’s measured in hours instead of days. The reason they’re able to do what the rest of us can only dream of is that these athletes can produce enormous amounts of power. Power is the rate at which cyclists burn energy and the energy they burn comes from the food they eat. And over the course of the Tour de France, the winning cyclist will burn the equivalent of roughly 210 Big Macs.

Cycling is a game of watts

To make a bicycle move, a Tour de France rider transfers energy from his muscles, through the bicycle and to the wheels that push back on the ground. The faster a rider can put out energy, the greater the power. This rate of energy transfer is often measured in watts. Tour de France cyclists are capable of generating enormous amounts of power for incredibly long periods of time compared to most people.

For about 20 minutes, a fit recreational cyclist can consistently put out 250 watts to 300 watts . Tour de France cyclists can produce over 400 watts for the same time period . These pros are even capable of hitting 1,000 watts for short bursts of time on a steep uphill – roughly enough power to run a microwave oven .

But not all of the energy a Tour de France cyclist puts into his bike gets turned into forward motion. Cyclists battle air resistance and frictional losses between their wheels and the road. They get help from gravity on downhills but they have to fight gravity while climbing.