What is the mating ritual of the albatross?

The albatross is a large seabird found across the southern oceans. Albatrosses are known for their elaborate mating rituals and lifelong pair bonds. The mating ritual of the albatross is a complex process that reinforces the strong lifelong bond between mating pairs.

The courtship ritual begins when albatrosses return to their breeding colonies after spending several years at sea. Unmated male albatrosses will arrive before the females and begin staking out nesting territories. They use vocal calls, posturing, and ritualized dances to establish dominance. This helps determine which birds will pair up for mating.

When a female albatross arrives at the colony, the male will initiate an elaborate mating dance to catch her attention. He spreads his wings, points his beak skyward, and sways back and forth. If the female is receptive, she will mirror his motions. The pair will dance together, billing and preening each other’s feathers. This dance helps the birds assess each other’s fitness for mating.

Pair Bond Formation

Once a pair of albatrosses takes a liking to each other, they will spend several days or weeks getting to know each other. They reinforce their bond by preening, sitting together, and sleeping side-by-side. The male will also search for a suitable nest site to impress his potential mate.

The pair will gradually synchronize their mating dance routines. This is a sign that their bond is strengthening. As the bond solidifies, the pair will breed for life. The female will lay a single egg that the parents take turns incubating for around 70 days.

Nesting Rituals

Albatrosses do not build nests in the traditional sense. They lay their egg directly on the bare ground or vegetation. However, mating pairs do engage in ritualized nesting behaviors.

Once the egg is laid, parents will develop an elaborate greeting ritual. Whenever one parent returns from sea to relieve the incubating partner, they engage in vocal calls, sky-pointing, and synchronized dancing. This helps reinforce their pair bond throughout the incubation period.

The nesting habitats of albatrosses are also hotbeds of ritualized territorial behavior. Albatrosses are highly aggressive in defending their nesting territories from intruders. They will stab at, bite, and slap trespassing birds with their large wings.

Chick Rearing

After hatching, the albatross chick is cared for by both parents. One parent will guard the chick while the other soars out to sea to hunt for food. When the foraging parent returns, mates perform elaborate greeting rituals. Then they exchange parenting duties so the other bird can go forage.

The mating rituals continue as the parents court each other during exchanges at the nest. This behavior strengthens their lifelong bond and ensures continued cooperation in raising their offspring.

As chicks get older, parents engage in ritualized behaviors to encourage them to fledge. They will stop feeding chicks, harass them verbally and physically, and even abandon them for short periods. This pushes the chick to take its first flight to sea.

Lifelong Bonds

Albatrosses maintain their pair bonds for life. Each year they reunite at the breeding colony and perform mating rituals. Even when they are too old to breed, albatross couples will still go through mating rituals. Their bonds last until one partner dies.

Unusual Courtship Rituals

Within the standard albatross mating sequence, researchers have noted intriguing exceptions. Some males have been observed courting other males with mating dances. Same-sex pairs will build nests together and even foster abandoned eggs. The motives are unknown, but this behavior reveals the complexity of albatross pair bonding instincts.

Interspecies breeding attempts also occur. Albatrosses may court penguins or other seabird species. But these instances rarely result in hybrid offspring. The strong natural instincts to find an albatross mate usually prevent outbreeding between species.

Regional Variations

Not all albatross species follow the same ritualistic mating behaviors. Some of the key regional differences include:

Laysan albatrosses

– Males build mud nest pedestals to attract females. – Ritualized beak fencing is common. – They perform moon-watching dances under the full moon.

Black-footed albatrosses

– Males throw their heads back during mating dances. – Pairs will tap their bills together when greeting. – They nod their heads during ritualized sky-pointing.

Wandering albatrosses

– Males clatter their bills to produce a rattling sound. – Crouching with dropped wings is a common courtship posture. – Pairs whistle duets when greeting each other.

Why Such Complex Rituals?

Scientists are not certain why albatrosses evolved such intricate mating rituals. But there are a few key theories:

– Rituals test and demonstrate fitness between potential mates. – Synchronized dances strengthen lifelong pair bonds. – Ritualized behaviors enhance cooperation in chick rearing. – Displays stimulate hormones that trigger breeding instincts. – Regular practice of rituals maintains bonds during long separations.

The elaborate rituals are energy-intensive displays that reveal important information about each bird’s health, experience, and commitment to mating for life.

The mating rituals of the albatross are sophisticated behavioral sequences passed down over generations. They form an important part of reinforcing monogamous bonds and breeding success. Pairs mate for life and continue performing rituals even after breeding years have passed. Regional variations exist between different species, but the core sequences of courtship dancing, pair bonding, territorial defense, and chick rearing remain similar across the albatross family. The rituals enhance communication, demonstrate fitness, stimulate breeding hormones, and maintain lifelong bonds. After years apart, albatross couples still recognize each other and renew their pair bond through intricate and beautiful mating dances.

Related Posts

What bird is similar to the tufted titmouse, do snowy owls bark or hoot, what is the description of a parasitic jaeger, how do you bandage a bird’s wing, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

Wandering Albatross

These remarkably efficient gliders, named after the Greek hero Diomedes, have the largest wingspan of any bird on the planet

Region: Antarctica

Destinations: Bouvet Island, Antarctic Peninsula, South Georgia

Name : Wandering Albatross, Snowy Albatross, White-winged Albatross ( Diomedea exulans )

Length: Up to 135 cm.

Weight : 6 to 12kg.

Location : All oceans except in the North Atlantic.

Conservation status : Vulnerable.

Diet : Cephalopods, small fish, crustaceans.

Appearance : White with grey-black wings, hooked bill.

How do Wandering Albatrosses feed?

Wandering Albatrosses make shallow dives when hunting. They’ll also attempt to eat almost anything they come across and will follow ships in the hopes of feeding on its garbage. They can gorge themselves so much that they become unable to fly and just have to float on the water.

How fast do Wandering Albatrosses fly?

Wandering Albatrosses can fly up to 40 km per hour.

What are Wandering Albatross mating rituals like?

Wandering Albatrosses mature sexually around 11 years of age. When courting, the male Wandering Albatross will spread his wings, wave his head around, and rap his bills against that of the female while making a braying noise. The pair will mate for life, breeding every 2 years. Mating season starts in early November with the Albatrosses creating nests of mud and grass on one of the Sub-Antarctic islands. The female will lay 1 egg about 10 cm long, sometime between the middle of December and early January. Incubation takes around 11 weeks, the parents taking turns. Once the chick is born the adults switch off between hunting and staying to care for the chick. The hunting parent returns to regurgitate stomach oil for the chick to feed on. Eventually both parents will start to hunt at the same time, visiting with the chick at widening intervals.

How long do Wandering Albatrosses live?

Wandering Albatrosses can live for over 50 years.

How many Wandering Albatrosses are there today?

There are about 25.200 adult Wandering Albatrosses in the world today.

Do Wandering Albatrosses have any natural predators?

Because they’re so big and spend almost all of their lives in flight, Wandering Albatrosses have almost no natural predators.

7 Wonderful Wandering Albatross Facts

- The Wandering Albatross is the largest member of its genus ( Diomedea ) and is one of the largest birds in the world.

- Wandering Albatrosses are also one of the best known and most studied species of birds.

- Diomedea refers to Diomedes, a hero in Greek mythology; of all the Acheaens he and Ajax were 2 nd only to Achilles in prowess. In mythology all of his companions turned into birds. Exulans is Latin for “exile” or “wanderer.”

- Wandering Albatrosses have the largest wingspan of any bird in the world today, stretching up to 3.5 metres across.

- Wandering Albatrosses are great gliders – they can soar through the sky without flapping their wings for several hours at a time. They’re so efficient at flying that they can actually use up less energy in the air than they would while sitting in a nest.

- Wandering Albatrosses have a special gland above their nasal passage that excretes a high saline solution. This helps keep salt level in their body, combating all the salt water they take in.

- Wandering Albatrosses get whiter the older they get.

Related cruises

Falkland Islands - South Georgia - Antarctica

Meet at least six penguin species!

PLA20-24 A cruise to the Falkland Islands, South Georgia & the Antarctic Peninsula. Visit some of the most beautiful arrays of wildlife on Earth. This journey will introduce you to at least 6 species of penguin and a whole lot of Antarctic fur seals!

m/v Plancius

Cruise date:

18 Oct - 7 Nov, 2024

Berths start from:

Antarctica - Basecamp - free camping, kayaking, snowshoe/hiking, photo workshop, mountaineering

The best activity voyage in Antarctica

HDS21a24 The Antarctic Peninsula Basecamp cruise offers you a myriad of ways to explore and enjoy the Antarctic Region. This expedition allows you to hike, snowshoe, kayak, go mountaineering, and even camp out under the Southern Polar skies.

m/v Hondius

1 Nov - 13 Nov, 2024

Weddell Sea – In search of the Emperor Penguin, incl. helicopters

Searching for the Elusive Emperor Penguins

OTL22-24 A true expedition, our Weddell Sea cruise sets out to explore the range of the Emperor Penguins near Snow Hill Island. We will visit the area via helicopter and see a variety of other birds and penguins including Adélies and Gentoos.

m/v Ortelius

10 Nov - 20 Nov, 2024

OTL23-24 A true expedition, our Weddell Sea cruise sets out to explore the range of the Emperor Penguins near Snow Hill Island. We will visit the area via helicopter and see a variety of other birds and penguins including Adélies and Gentoos.

20 Nov - 30 Nov, 2024

Antarctica - Basecamp - free camping, kayaking, snowshoe/hiking, mountaineering, photo workshop

HDS23-24 The Antarctic Peninsula Basecamp cruise offers you a myriad of ways to explore and enjoy the Antarctic Region. This expedition allows you to hike, snowshoe, kayak, go mountaineering, and even camp out under the Southern Polar skies.

23 Nov - 5 Dec, 2024

We have a total of 62 cruises

Overview of Albatross Breeding Habits

Albatrosses are large, seabird species of the family Diomedeidae whose wingspan can range from 8 to 12 feet in some species. Albatrosses are found mainly in the southern hemisphere, and they breed in colonies on remote islands and coasts. Breeding albatrosses typically form monogamous pairs, and they engage in ritualized courtship displays that involve synchronous movements and bill circles. They are also known for their elaborate nesting displays, which involve the birds gathering materials such as grass, mud, and feathers to build a nest.

Albatross Breeding Rituals

Breeding albatrosses typically mate for life, and they often return to the same nesting site year after year. Before mating, the birds engage in a complex courtship ritual that involves synchronous movements and bill circles. The male albatross will also offer the female gifts such as food, feathers, and grass to win her favor. Once the pair has mated, they will work together to build their nest. This process involves gathering materials such as grass, mud, and feathers to construct the nest. The birds will then use their beaks to shape and mold the materials into the desired shape.

Albatross Nesting Behaviors

Once the nest is built, the albatrosses will lay a single egg in it. The parents will then take turns incubating the egg and providing food for their chick once it hatches. Albatrosses are known for their long-distance flights and they use this ability to find food for their young. They will travel hundreds of miles in search of fish, squid, and other sources of food that they can bring back to their nesting site. Once the chick is old enough, the parents will teach it how to fly and hunt for food.

Conservation and Protection of Albatrosses

Albatrosses are an important part of many oceanic ecosystems, and their numbers have been declining due to human activities. Longline fishing, plastic pollution, and climate change are all threats to albatross populations. To protect these birds, many countries have established marine protected areas and have put restrictions in place to reduce the impact of fishing on albatross populations. In addition, organizations such as the Albatross Task Force are working hard to research and protect these majestic birds.

Albatrosses are amazing birds, and their breeding habits and nesting behaviors are fascinating. They mate for life and engage in complex courtship rituals, and they travel long distances to find food for their young. Unfortunately, human activities are putting albatross populations at risk. To protect these birds, it is important to reduce the impacts of fishing, plastic pollution, and climate change. Furthermore, organizations such as the Albatross Task Force are actively working to research and protect these birds.

Similar Posts

Dietary Diversity: What Cranes Eat and Why It Matters

Dietary Diversity Cranes are beautiful, long-legged birds that can typically be found in wetlands and grasslands. They have a…

Navigating the Complex Digestive System of Aardvarks

Introduction The aardvark is an interesting creature that has captivated the attention of many. Not only do they have…

Diving Deeper into the Social Habits of the Echidna

Introduction The echidna is one of the most curious creatures in the animal kingdom. These small, spiny animals are…

Vital Facts About Dolphins

Introduction Dolphins are one of the most beloved and iconic species on the planet. They are intelligent, social mammals…

A Natural History of the Crocodile

Overview of the Crocodile Crocodiles are a species of reptiles that are found all over the world, from tropical…

Alligator Hunting: The Pros and Cons

Introduction The alligator is an iconic species found in both fresh and brackish waters throughout the southeastern United States….

Animal encyclopedia

Exploring the magnificent wandering albatross.

September 4, 2023

John Brooks

September 4, 2023 / Reading time: 6 minutes

Sophie Hodgson

We adhere to editorial integrity are independent and thus not for sale. The article may contain references to products of our partners. Here's an explanation of how we make money .

Why you can trust us

Wild Explained was founded in 2021 and has a long track record of helping people make smart decisions. We have built this reputation for many years by helping our readers with everyday questions and decisions. We have helped thousands of readers find answers.

Wild Explained follows an established editorial policy . Therefore, you can assume that your interests are our top priority. Our editorial team is composed of qualified professional editors and our articles are edited by subject matter experts who verify that our publications, are objective, independent and trustworthy.

Our content deals with topics that are particularly relevant to you as a recipient - we are always on the lookout for the best comparisons, tips and advice for you.

Editorial integrity

Wild Explained operates according to an established editorial policy . Therefore, you can be sure that your interests are our top priority. The authors of Wild Explained research independent content to help you with everyday problems and make purchasing decisions easier.

Our principles

Your trust is important to us. That is why we work independently. We want to provide our readers with objective information that keeps them fully informed. Therefore, we have set editorial standards based on our experience to ensure our desired quality. Editorial content is vetted by our journalists and editors to ensure our independence. We draw a clear line between our advertisers and editorial staff. Therefore, our specialist editorial team does not receive any direct remuneration from advertisers on our pages.

Editorial independence

You as a reader are the focus of our editorial work. The best advice for you - that is our greatest goal. We want to help you solve everyday problems and make the right decisions. To ensure that our editorial standards are not influenced by advertisers, we have established clear rules. Our authors do not receive any direct remuneration from the advertisers on our pages. You can therefore rely on the independence of our editorial team.

How we earn money

How can we earn money and stay independent, you ask? We'll show you. Our editors and experts have years of experience in researching and writing reader-oriented content. Our primary goal is to provide you, our reader, with added value and to assist you with your everyday questions and purchasing decisions. You are wondering how we make money and stay independent. We have the answers. Our experts, journalists and editors have been helping our readers with everyday questions and decisions for over many years. We constantly strive to provide our readers and consumers with the expert advice and tools they need to succeed throughout their life journey.

Wild Explained follows a strict editorial policy , so you can trust that our content is honest and independent. Our editors, journalists and reporters create independent and accurate content to help you make the right decisions. The content created by our editorial team is therefore objective, factual and not influenced by our advertisers.

We make it transparent how we can offer you high-quality content, competitive prices and useful tools by explaining how each comparison came about. This gives you the best possible assessment of the criteria used to compile the comparisons and what to look out for when reading them. Our comparisons are created independently of paid advertising.

Wild Explained is an independent, advertising-financed publisher and comparison service. We compare different products with each other based on various independent criteria.

If you click on one of these products and then buy something, for example, we may receive a commission from the respective provider. However, this does not make the product more expensive for you. We also do not receive any personal data from you, as we do not track you at all via cookies. The commission allows us to continue to offer our platform free of charge without having to compromise our independence.

Whether we get money or not has no influence on the order of the products in our comparisons, because we want to offer you the best possible content. Independent and always up to date. Although we strive to provide a wide range of offers, sometimes our products do not contain all information about all products or services available on the market. However, we do our best to improve our content for you every day.

Table of Contents

The Wandering Albatross is a truly remarkable bird that captivates the imagination of wildlife enthusiasts and researchers alike. With its impressive wingspan and majestic flight, this magnificent creature has a unique story to tell. In this article, we will delve into the world of the Wandering Albatross, exploring its characteristics, habitat, life cycle, diet, threats, conservation efforts, and even its role in culture and literature.

Understanding the Wandering Albatross

The Wandering Albatross, a majestic seabird, is a fascinating creature that captures the imagination with its impressive size and unique characteristics . Let’s delve deeper into the defining features and habitat of this remarkable bird.

Defining Characteristics of the Wandering Albatross

With a wingspan of up to 11 feet, the Wandering Albatross boasts the largest wingspan of any bird in the world. This remarkable wingspan allows it to glide effortlessly over the vast open oceans it calls home. As it soars through the air, its wingspan creates a mesmerizing spectacle, showcasing the bird’s incredible adaptability to its environment.

The Wandering Albatross is easily recognizable by its distinctive white feathers , sleek body, and long, slender wings . These defining features not only contribute to its graceful appearance but also serve a purpose in its survival. The white feathers help camouflage the bird against the bright sunlight reflecting off the ocean’s surface, while the sleek body and long wings enable it to navigate the winds with precision.

The Albatross’s Unique Habitat

These graceful birds are found primarily in the southern oceans, particularly around the Antarctic region. The vast expanse of the Southern Ocean provides an ideal environment for the Wandering Albatross to thrive. With its ability to cover immense distances, the bird utilizes the strong winds to its advantage, effortlessly gliding across the ocean in search of food and suitable breeding grounds.

During their long journeys, Wandering Albatrosses traverse various oceanic regions, from the sub-Antarctic to as far as the coast of South America. Their nomadic lifestyle allows them to explore different ecosystems , adapting to the ever-changing conditions of the open ocean.

When on land, the Wandering Albatross prefers remote and isolated islands for nesting. These islands provide the perfect breeding environment, away from human disturbance and terrestrial predators. Here, amidst the rugged cliffs and pristine beaches, the albatrosses establish their colonies, creating a spectacle of life in the midst of the vast ocean.

These incredible birds are known to return to the same nesting sites year after year, demonstrating their strong site fidelity . The remote islands become their sanctuary, where they engage in courtship rituals, build nests, and raise their young. It is a testament to their resilience and adaptability that they have managed to maintain these nesting sites for generations, despite the challenges they face in the ever-changing world.

As we continue to explore and understand the Wandering Albatross, we uncover more about its remarkable adaptations, behaviors, and interactions with its environment. The more we learn, the more we appreciate the intricate web of life that exists in the vast oceans, where these magnificent birds reign supreme.

The Life Cycle of the Wandering Albatross

Breeding and nesting patterns.

The breeding season for the Wandering Albatross begins in the austral summer months, with courtship rituals that involve intricate displays of dance and vocalizations . These courtship displays are not only a way for the albatrosses to attract a mate but also a means of establishing dominance within their colony. The males showcase their impressive wingspan and perform elaborate dances, while the females respond with their own graceful movements.

Once a pair bonds, they establish a nest on the chosen island and begin the process of reproduction. The nests are carefully constructed using a combination of soil, grass, and other materials found on the island. The albatrosses take great care in selecting the perfect location for their nest, ensuring it is protected from the harsh elements and predators.

The female typically lays a single egg, which both parents take turns incubating. Incubation lasts for approximately 60 days, during which the parents rotate shifts to keep the egg warm and protected. This shared responsibility is a testament to the strong bonds formed between Wandering Albatross pairs. The parents take turns leaving the nest to search for food, returning to regurgitate the nutrient-rich meal for their growing chick.

During the incubation period, the albatrosses face numerous challenges. They must withstand strong winds, freezing temperatures, and potential threats from predators . Despite these difficulties, the dedicated parents remain vigilant, ensuring the survival of their offspring.

Growth and Development Stages

After hatching, the chicks are cared for and fed by both parents. The parents regurgitate a nutrient-rich oil that provides essential nourishment for the growing chick. This feeding process continues for several months until the chick becomes independent enough to forage on its own. The oil not only provides the necessary nutrients but also helps to strengthen the chick’s immune system, protecting it from potential diseases.

As the chick grows, it undergoes various developmental stages. Its downy feathers gradually give way to juvenile plumage, which is darker in coloration. The chick’s beak also undergoes changes, becoming stronger and more adapted to catching prey. During this time, the parents continue to provide guidance and protection, teaching the chick essential survival skills.

It takes years for a Wandering Albatross chick to reach maturity. During this time, they undergo a remarkable transformation, gradually developing their characteristic white plumage and mastering their flight skills. The albatrosses spend a significant portion of their juvenile years at sea, honing their flying abilities and exploring vast oceanic territories. It is during this period that they face various challenges, including encounters with other seabirds and potential threats from human activities.

It is this lengthy growth period that contributes to the vulnerability of this species and its slow population recovery. The Wandering Albatross faces numerous threats, including habitat loss, climate change, and accidental capture in fishing gear. Conservation efforts are crucial to ensure the survival of these magnificent birds and their unique life cycle.

The Wandering Albatross’s Diet and Hunting Techniques

Preferred prey and hunting grounds.

The Wandering Albatross is primarily a scavenger, feeding on a variety of marine organisms, including squid, fish, and crustaceans. They use their keen eyesight to spot potential prey items floating on the ocean surface, and once sighted, they plunge-dived from great heights to capture their meal. Additionally, these birds are known to scavenge carrion and exploit fishing vessels for an easy meal.

Adaptations for Hunting in the Open Ocean

Surviving in the harsh oceanic environment requires specialized adaptations, and the Wandering Albatross is well-equipped for the task. Its long wings enable it to glide effortlessly for long periods, conserving energy during hours of flight. The bird’s keen sense of smell allows it to locate food sources, even from great distances. These adaptations make the Wandering Albatross a formidable hunter and a vital component of the oceanic ecosystem.

Threats and Conservation Efforts

Human impact on the wandering albatross.

Despite their grace and beauty, Wandering Albatrosses face numerous threats that have contributed to their decline. One of the main challenges is the destructive impact of longline fishing operations, where the birds mistakenly become hooked or tangled in the fishing gear. Additionally, pollution, habitat degradation, and climate change further jeopardize the survival of these birds.

Current Conservation Strategies and Their Effectiveness

To safeguard the future of the Wandering Albatross, concerted conservation efforts are underway. Several measures have been implemented, including the establishment of protected areas and marine reserves, the development of guidelines for responsible fishing practices, and public awareness campaigns to promote the importance of nurturing this iconic species. While progress has been made, continued efforts are required to ensure the recovery and long-term survival of the Wandering Albatross.

The Role of the Wandering Albatross in Culture and Literature

Symbolism and significance in various cultures.

Throughout history, the Wandering Albatross has held deep cultural significance in many communities. In some cultures, these birds are considered symbols of loyalty, freedom, and endurance. They are often associated with seafaring traditions and are believed to bring good fortune to sailors.

The Albatross in Classic and Contemporary Literature

The haunting imagery of the Wandering Albatross has inspired numerous works of literature. Perhaps the most famous reference is found in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” where an albatross is depicted as a harbinger of both good and ill fortune. Furthermore, many modern authors have woven the essence of the Wandering Albatross into their stories, capturing its mystique and its role as a symbol of the natural world.

In conclusion, the Wandering Albatross is a remarkable bird with a captivating presence. From its unique characteristics to its adaptations for survival in the open ocean , this magnificent creature enthralls all who encounter it. However, its existence is threatened by human activities and environmental changes. Through ongoing conservation efforts and a deeper appreciation of its cultural significance, we can work towards ensuring a future where the Wandering Albatross continues to grace the skies above the vast southern oceans.

Related articles

- Fresh Food for Cats – The 15 best products compared

- The Adorable Zuchon: A Guide to This Cute Hybrid Dog

- Exploring the Unique Characteristics of the Zorse

- Meet the Zonkey: A Unique Hybrid Animal

- Uncovering the Secrets of the Zokor: A Comprehensive Overview

- Understanding the Zebu: An Overview of the Ancient Cattle Breed

- Uncovering the Fascinating World of Zebrafish

- Watch Out! The Zebra Spitting Cobra is Here

- The Fascinating Zebra Tarantula: A Guide to Care and Maintenance

- The Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker: A Closer Look

- Uncovering the Mystery of the Zebra Snake

- The Amazing Zebra Pleco: All You Need to Know

- Discovering the Fascinating Zebra Shark

- Understanding the Impact of Zebra Mussels on Freshwater Ecosystems

- Caring for Your Zebra Finch: A Comprehensive Guide

- The Fascinating World of Zebras

- The Adorable Yorkshire Terrier: A Guide to Owning This Lovable Breed

- The Adorable Yorkie Poo: A Guide to This Popular Dog Breed

- The Adorable Yorkie Bichon: A Perfect Pet for Any Home

- The Adorable Yoranian: A Guide to This Sweet Breed

- Discover the Deliciousness of Yokohama Chicken

- Uncovering the Mystery of the Yeti Crab

- Catching Yellowtail Snapper: A Guide to the Best Fishing Spots

- The Brightly Colored Yellowthroat: A Guide to Identification

- Identifying and Dealing with Yellowjacket Yellow Jackets

- The Yellowish Cuckoo Bumblebee: A Formerly Endangered Species

- The Yellowhammer: A Symbol of Alabama’s Pride

- The Benefits of Eating Yellowfin Tuna

- The Yellow-Faced Bee: An Overview

- The Majestic Yellow-Eyed Penguin

- The Yellow-Bellied Sea Snake: A Fascinating Creature

- The Benefits of Keeping a Yellow Tang in Your Saltwater Aquarium

- The Beautiful Black and Yellow Tanager: A Closer Look at the Yellow Tanager

- The Fascinating Yellow Spotted Lizard

- What You Need to Know About the Yellow Sac Spider

- Catching Yellow Perch: Tips for a Successful Fishing Trip

- The Growing Problem of Yellow Crazy Ants

- The Rare and Beautiful Yellow Cobra

- The Yellow Bullhead Catfish: An Overview

- Caring for a Yellow Belly Ball Python

- The Impact of Yellow Aphids on Agriculture

- Catching Yellow Bass: Tips and Techniques for Success

- The Striking Beauty of the Yellow Anaconda

- Understanding the Yarara: A Guide to This Unique Reptile

- The Yakutian Laika: An Overview of the Ancient Arctic Dog Breed

- The Fascinating World of Yaks: An Introduction

- Everything You Need to Know About Yabbies

- The Xoloitzcuintli: A Unique Breed of Dog

- Uncovering the Mystery of Xiongguanlong: A Newly Discovered Dinosaur Species

- Uncovering the Mysteries of the Xiphactinus Fish

- Camp Kitchen

- Camping Bags

- Camping Coolers

- Camping Tents

- Chair Rockers

- Emergency Sets

- Flashlights & Lanterns

- Grills & Picnic

- Insect Control

- Outdoor Electrical

- Sleeping Bags & Air Beds

- Wagons & Carts

- Beds and furniture

- Bowls and feeders

- Cleaning and repellents

- Collars, harnesses and leashes

- Crates, gates and containment

- Dental care and wellness

- Flea and tick

- Food and treats

- Grooming supplies

- Health and wellness

- Litter and waste disposal

- Toys for cats

- Vitamins and supplements

- Dog apparel

- Dog beds and pads

- Dog collars and leashes

- Dog harnesses

- Dog life jackets

- Dog travel gear

- Small dog gear

- Winter dog gear

© Copyright 2024 | Imprint | Privacy Policy | About us | How we work | Editors | Advertising opportunities

Certain content displayed on this website originates from Amazon. This content is provided "as is" and may be changed or removed at any time. The publisher receives affiliate commissions from Amazon on eligible purchases.

{{ searchResult.title }}

Wandering Albatross

Diomedea exulans

Known for its majestic wingspan and far-ranging travels, the Wandering Albatross is a captivating presence in the Southern Ocean's expanse. As the bird with the widest wingspan globally, this remarkable creature glides effortlessly across vast oceanic distances, its brilliant white plumage and solitary habits making it a unique symbol of the wild, open sea.

On this page

Appearance and Identification

Vocalization and sounds, behavior and social structure, distribution and habitat, lifespan and life cycle, conservation status, similar birds.

Males and females have similar plumage

Primary Color

Primary color (juvenile), secondary colors.

Black, Grey

Secondary Colors (female)

Secondary colors (juvenile).

White, Grey

Secondary Colors (seasonal)

Wing color (juvenile).

Large, Hooked

Beak Color (juvenile)

Leg color (juvenile), distinctive markings.

Black wings, white tail, large pink beak

Distinctive Markings (juvenile)

Darker than adults, brown beak

Tail Description

White with black edges

Tail Description (juvenile)

Brown with white edges

Size Metrics

107cm to 135cm

250cm to 350cm

6.72kg to 12kg

Click on an image below to see the full-size version

Pair of Wandering Albatrosses

Juvenile Wandering Albatross

Wandering Albatross resting on the sea

Wandering Albatross in-flight over the ocean

Wandering Albatross at nest with downy chick

Primary Calls

Series of grunts and whistles

Call Description

Most vocal on breeding grounds, otherwise silent

Alarm Calls

Loud, harsh squawks

Daily Activities

Active during day, rests on water surface at night

Social Habits

Solitary at sea, social on breeding grounds

Territorial Behavior

Defends nest site during breeding season

Migratory Patterns

Non-migratory but wanders widely at sea

Interaction with Other Species

Occasionally forms loose flocks at sea

Primary Diet

Fish, Squid

Feeding Habits

Surface seizes and scavenges

Feeding Times

Day and night

Prey Capture Method

Plunge-diving, surface-seizing

Diet Variations

May eat carrion

Special Dietary Needs (if any)

Nesting location.

On ground on isolated islands

Nest Construction

Mound of mud and vegetation

Breeding Season

Every other year

Number of clutches (per breeding season)

Once every two years

Egg Appearance

White, oval

Clutch Characteristics

Incubation period.

Around 80 days

Fledgling Period

Approximately 9 months

Parental Care

Both parents incubate and feed chick

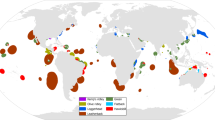

Geographic Range

Circumpolar in Southern Ocean

Habitat Description

Open ocean, breeds on remote islands

Elevation Range

Migration patterns, climate zones.

Polar, Temperate

Distribution Map

Please note, this range and distribution map is a high-level overview, and doesn't break down into specific regions and areas of the countries.

Non-breeding

Lifespan range (years)

Average lifespan, maturity age.

7-10 year(s)

Breeding Age

Reproductive behavior.

Monogamous, long-term pair bonds

Age-Related Changes

Younger birds are darker, gain white plumage with age

Current Status

Vulnerable (IUCN Red List)

Major Threats

Longline fishing, plastic ingestion, climate change

Conservation Efforts

Protected under international law, conservation programs on breeding islands

Population Trend

Slow but steady population decrease due to threats

Royal Albatross

Diomedea epomophora

Classification

Other names:

Snowy Albatross, White-winged Albatross

Population size:

Population trend:

Conservation status:

IUCN Red List

Get the best of Birdfact

Brighten up your inbox with our exclusive newsletter , enjoyed by thousands of people from around the world.

Your information will be used in accordance with Birdfact's privacy policy . You may opt out at any time.

© 2024 - Birdfact. All rights reserved. No part of this site may be reproduced without our written permission.

Animal Diversity Web

- About Animal Names

- Educational Resources

- Special Collections

- Browse Animalia

More Information

Additional information.

- Encyclopedia of Life

Diomedea exulans wandering albatross

Geographic Range

Wandering albatrosses are found almost exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere, although occasional sightings just north of the Equator have been reported. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

There is some disagreement over how many subspecies of wandering albatross ( Diomedea exulans ) there are, and whether they should be considered separate species. Most subspecies of Diomedea exulans are difficult to tell apart, especially as juveniles, but DNA analyses have shown that significant differences exist. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

Diomedea exulans exulans breeds on South Georgia, Prince Edward, Marion, Crozet, Kerguelen, and Macquarie islands. Diomedea exulans dabbenena occurs on Gough and Inaccessible islands, ranging over the Atlantic Ocean to western coastal Africa. Diomedea exulans antipodensis is found primarily on the Antipodes of New Zealand, and ranges at sea from Chile to eastern Australia. Diomedea exulans amsterdamensis is found only on Amsterdam Island and the surrounding seas. Other subspecies names that have become obsolete include Diomedea exulans gibsoni , now commonly considered part of D. e. antipodensis , and Diomedea exulans chionoptera , considered part of D. e. exulans . ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- Biogeographic Regions

Wandering albatrosses breed on several subantarctic islands, which are characterized by peat soils, tussock grass, sedges, mosses, and shrubs. Wandering albatrosses nest in sheltered areas on plateaus, ridges, plains, or valleys.

Outside of the breeding season, wandering albatrosses are found only in the open ocean, where food is abundant. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- Habitat Regions

- terrestrial

- saltwater or marine

- Terrestrial Biomes

- savanna or grassland

- Aquatic Biomes

Physical Description

All subspecies of wandering albatrosses have extremely long wingspans (averaging just over 3 meters), white underwing coverts, and pink bills. Adult body plumage ranges from pure white to dark brown, and the wings range from being entirely blackish to a combination of black with white coverts and scapulars. They are distinguished from the closely related royal albatross by their white eyelids, pink bill color, lack of black on the maxilla, and head and body shape. On average, males have longer bills, tarsi, tails, and wings than females. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Juveniles of all subspecies are very much alike; they have chocolate-brown plumage with a white face and black wings. As individuals age, most become progressively whiter with each molt, starting with the back. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

D. e. exulans averages larger than other recognized subspecies, and is the only taxon that achieves fully white body plumage, and this only in males. Although females do not become pure white, they can still be distinguished from other subspecies by color alone. Adults also have mostly white coverts, with black only on the primaries and secondaries. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Adults of D. e. amsterdamensis have dark brown plumage with white faces and black crowns, and are distinguished from juveniles by their white bellies and throats. In addition to their black tails, they also have a black stripe along the cutting edge of the maxilla, a character otherwise found in D. epomophora but not other forms of D. exulans . Males and females are similar in plumage. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Adults of D. e. antipodensis display sexual dimorphism in plumage, with older males appearing white with some brown splotching, while adult females have mostly brown underparts and a white face. Both sexes also have a brown breast band. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

With age, D. e. dabbenena gradually attains white plumage, although it never becomes as white as male D. e. exulans . The wing coverts also appear mostly black, although there may be white patches. Females have more brown splotches than males, and have less white in their wing coverts. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Other Physical Features

- endothermic

- homoiothermic

- bilateral symmetry

- Sexual Dimorphism

- sexes alike

- male larger

- sexes colored or patterned differently

- Average mass 8130 g 286.52 oz AnAge

- Range length 1.1 to 1.35 m 3.61 to 4.43 ft

- Range wingspan 2.5 to 3.5 m 8.20 to 11.48 ft

- Average wingspan 3.1 m 10.17 ft

- Average basal metabolic rate 20.3649 W AnAge

Reproduction

Wandering albatrosses have a biennial breeding cycle, and pairs with chicks from the previous season co-exist in colonies with mating and incubating pairs. Pairs unsuccessful in one year may try to mate again in the same year or the next one, but their chances of successfully rearing young are low. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

After foraging at sea, males arrive first at the same breeding site every year within days of each other. They locate and reuse old nests or sometimes create new ones. Females arrive later, over the course of a few weeks. Wandering albatrosses have a monogamous mating strategy, forming pair bonds for life. Females may bond temporarily with other males if their partner and nest are not readily visible. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Mating System

Copulation occurs in the austral summer, usually around December (February for D. e. amsterdamensis ). Rape and extra-pair copulations are frequent, despite their monogamous mating strategy. Pairs nest on slopes or valleys, usually in the cover of grasses or shrubs. Nests are depressions lined with grass, twigs, and soil. A single egg is laid and, if incubation or rearing fails, pairs usually wait until the following year to try again. Both parents incubate eggs, which takes about 78 days on average. Although females take the first shift, males are eager to take over incubation and may forcefully push females off the egg. Untended eggs are in danger of predation by skuas ( Stercorarius ) and sheathbills ( Chionis ). ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

After the chick hatches, they are brooded for about 4 to 6 weeks until they can be left alone at the nest. Males and females alternate foraging at sea. Following the brooding period, both parents leave the chick by itself while they forage. The chicks are entirely dependent on their parents for food for 9 to 10 months, and may wait weeks for them to return. Chicks are entirely independent once they fledge. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Some individuals may reach sexual maturity by age 6. Immature, non-breeding individuals will return to the breeding site. Group displays are common among non-breeding adults, but most breeding adults do not participate. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Key Reproductive Features

- iteroparous

- seasonal breeding

- gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate)

- Breeding interval Breeding occurs biennially, possibly annually if the previous season's attempt fails.

- Breeding season Breeding occurs from December through March.

- Average eggs per season 1

- Range time to hatching 74 to 85 days

- Range fledging age 7 to 10 months

- Range time to independence 7 to 10 months

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female) 6 to 22 years

- Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female) 10 years

- Range age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male) 6 to 22 years

- Average age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male) 10 years

Males choose the nesting territory, and stay at the nest site more than females before incubation. Parents alternate during incubation, and later during brooding and feeding once the chick is old enough to be left alone at the nest. Although there is generally equal parental investment, males will tend to invest more as the chick nears fledging. Occasionally, a single parent may successfully rear its chick. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Parental Investment

- provisioning

Lifespan/Longevity

Wandering albatrosses are long-lived. An individual nicknamed "Grandma" was recorded to live over 60 years in New Zealand. Due to the late onset of maturity, with the average age at first breeding about 10 years, such longevity is not unexpected. However, there is fairly high chick mortality, ranging from 30 to 75%. Their slow breeding cycle and late onset of maturity make wandering albatrosses highly susceptible to population declines when adults are caught as bycatch in fishing nets. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Range lifespan Status: wild 60 (high) years

- Average lifespan Status: wild 415 months Bird Banding Laboratory

While foraging at sea, wandering albatrosses travel in small groups. Large feeding frenzies may occur around fishing boats. Individuals may travel thousands of kilometers away from their breeding grounds, even occasionally crossing the equator.

During the breeding season, Wandering albatrosses are gregarious and displays are common (see “Communication and Perception” section, below). Vocalizations and displays occur during mating or territorial defense. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- Key Behaviors

- territorial

- Average territory size 1 m^2

Wandering albatrosses defend small nesting territories, otherwise the range within which they travel is many thousands of square kilometers. ( Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

Communication and Perception

Displays and vocalizations are common when defending territory or mating. They include croaks, bill-clapping, bill-touching, skypointing, trumpeting, head-shaking, the "ecstatic" gesture, and "the gawky-look". Individuals may also vocalize when fighting over food. ( Shirihai, 2002 )

- Communication Channels

- Perception Channels

Food Habits

Wandering albatrosses primarily eat fish, such as toothfish ( Dissostichus ), squids, other cephalopods, and occasional crustaceans. The primary method of foraging is by surface-seizing, but they have the ability to plunge and dive up to 1 meter. They will sometimes follow fishing boats and feed on catches with other Procellariiformes , which they usually outcompete because of their size. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- Primary Diet

- molluscivore

- Animal Foods

- aquatic crustaceans

Although humans formerly hunted wandering albatrosses as food, adults currently have no predators. Their large size, sharp bill, and occasionally aggressive behavior make them undesirable opponents. However, some are inadvertently caught during large-scale fishing operations.

Chicks and eggs, on the other hand, are susceptible to predation from skuas and sheathbills, and formerly were harvested by humans as well. Eggs that fall out of nests or are unattended are quickly preyed upon. Nests are frequently sheltered with plant material to make them less conspicuous. Small chicks that are still in the brooding stage are easy targets for large carnivorous seabirds. Introduced predators, including mice, pigs, cats, rats, and goats are also known to eat eggs and chicks. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 ; Tickell, 1968 )

- skuas ( Stercorariidae )

- sheathbills ( Chionis )

- domestic cats ( Felis silvestris )

- introduced pigs ( Sus scrofa )

- introduced goats ( Capra hircus )

- introduced rats ( Rattus rattus and Rattus norvegicus )

- introduced mice ( Mus musculus )

Ecosystem Roles

Wandering albatrosses are predators, feeding on fish, cephalopods, and crustaceans. They are known for their ability to compete with other seabirds for food, particularly near fishing boats. Although adult birds, their eggs, and their chicks were formerly a source of food to humans, such practices have been stopped. ( IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

Economic Importance for Humans: Positive

Wandering albatrosses have extraordinary morphology, with perhaps the longest wingspan of any bird. Their enormous size also makes them popular in ecotourism excursions, especially for birders. Declining population numbers also mean increased conservation efforts. Their relative tameness towards humans makes them ideal for research and study. ( Shirihai, 2002 )

- Positive Impacts

- research and education

Economic Importance for Humans: Negative

Wandering albatrosses, along with other seabirds, follow fishing boats to take advantage of helpless fish and are reputed to reduce economic output from these fisheries. Albatrosses also become incidental bycatch, hampering conservation efforts. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

Conservation Status

Diomedea exulans exulans and Diomedea exulans antipodensis are listed by the IUCN Red list and Birdlife International as being vulnerable; Diomedea exulans dabbenena is listed as endangered, and Diomedea exulans amsterdamensis is listed as critically endangered.

All subspecies of Diomedea exulans are highly vulnerable to becoming bycatch of commercial fisheries, and population declines are mostly attributed to this. Introduced predators such as feral cats , pigs , goats , and rats on various islands leads to high mortality rates of chicks and eggs. Diomedea exulans amsterdamensis is listed as critically endangered due to introduced predators, risk of becoming bycatch, small population size, threat of chick mortality by disease, and loss of habitat to cattle farming.

Some conservation measures that have been taken include removal of introduced predators from islands, listing breeding habitats as World Heritage Sites, fishery relocation, and population monitoring. ( Birdlife International, 2006 ; IUCN, 2006 ; Shirihai, 2002 )

- IUCN Red List Vulnerable More information

- US Migratory Bird Act No special status

- US Federal List No special status

- CITES No special status

Contributors

Tanya Dewey (editor), Animal Diversity Web.

Lauren Scopel (author), Michigan State University, Pamela Rasmussen (editor, instructor), Michigan State University.

the body of water between Africa, Europe, the southern ocean (above 60 degrees south latitude), and the western hemisphere. It is the second largest ocean in the world after the Pacific Ocean.

body of water between the southern ocean (above 60 degrees south latitude), Australia, Asia, and the western hemisphere. This is the world's largest ocean, covering about 28% of the world's surface.

uses sound to communicate

young are born in a relatively underdeveloped state; they are unable to feed or care for themselves or locomote independently for a period of time after birth/hatching. In birds, naked and helpless after hatching.

having body symmetry such that the animal can be divided in one plane into two mirror-image halves. Animals with bilateral symmetry have dorsal and ventral sides, as well as anterior and posterior ends. Synapomorphy of the Bilateria.

an animal that mainly eats meat

uses smells or other chemicals to communicate

the nearshore aquatic habitats near a coast, or shoreline.

used loosely to describe any group of organisms living together or in close proximity to each other - for example nesting shorebirds that live in large colonies. More specifically refers to a group of organisms in which members act as specialized subunits (a continuous, modular society) - as in clonal organisms.

- active during the day, 2. lasting for one day.

humans benefit economically by promoting tourism that focuses on the appreciation of natural areas or animals. Ecotourism implies that there are existing programs that profit from the appreciation of natural areas or animals.

animals that use metabolically generated heat to regulate body temperature independently of ambient temperature. Endothermy is a synapomorphy of the Mammalia, although it may have arisen in a (now extinct) synapsid ancestor; the fossil record does not distinguish these possibilities. Convergent in birds.

offspring are produced in more than one group (litters, clutches, etc.) and across multiple seasons (or other periods hospitable to reproduction). Iteroparous animals must, by definition, survive over multiple seasons (or periodic condition changes).

eats mollusks, members of Phylum Mollusca

Having one mate at a time.

having the capacity to move from one place to another.

the area in which the animal is naturally found, the region in which it is endemic.

generally wanders from place to place, usually within a well-defined range.

islands that are not part of continental shelf areas, they are not, and have never been, connected to a continental land mass, most typically these are volcanic islands.

reproduction in which eggs are released by the female; development of offspring occurs outside the mother's body.

An aquatic biome consisting of the open ocean, far from land, does not include sea bottom (benthic zone).

an animal that mainly eats fish

the regions of the earth that surround the north and south poles, from the north pole to 60 degrees north and from the south pole to 60 degrees south.

mainly lives in oceans, seas, or other bodies of salt water.

breeding is confined to a particular season

reproduction that includes combining the genetic contribution of two individuals, a male and a female

associates with others of its species; forms social groups.

uses touch to communicate

that region of the Earth between 23.5 degrees North and 60 degrees North (between the Tropic of Cancer and the Arctic Circle) and between 23.5 degrees South and 60 degrees South (between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Antarctic Circle).

Living on the ground.

defends an area within the home range, occupied by a single animals or group of animals of the same species and held through overt defense, display, or advertisement

A terrestrial biome. Savannas are grasslands with scattered individual trees that do not form a closed canopy. Extensive savannas are found in parts of subtropical and tropical Africa and South America, and in Australia.

A grassland with scattered trees or scattered clumps of trees, a type of community intermediate between grassland and forest. See also Tropical savanna and grassland biome.

A terrestrial biome found in temperate latitudes (>23.5° N or S latitude). Vegetation is made up mostly of grasses, the height and species diversity of which depend largely on the amount of moisture available. Fire and grazing are important in the long-term maintenance of grasslands.

uses sight to communicate

Birdlife International, 2006. "Species factsheets" (On-line). Accessed November 07, 2006 at http://www.birdlife.org .

IUCN, 2006. "2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species" (On-line). Accessed November 06, 2006 at http://www.iucnredlist.org .

Shirihai, H. 2002. The Complete Guide to Antarctic Wildlife . New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Tickell, W. 1968. Biology of Great Albatrosses. Pp. 1-53 in Antarctic Bird Studies . Baltimore: Horn-Schafer.

The Animal Diversity Web team is excited to announce ADW Pocket Guides!

Read more...

Search in feature Taxon Information Contributor Galleries Topics Classification

- Explore Data @ Quaardvark

- Search Guide

Navigation Links

Classification.

- Kingdom Animalia animals Animalia: information (1) Animalia: pictures (22861) Animalia: specimens (7109) Animalia: sounds (722) Animalia: maps (42)

- Phylum Chordata chordates Chordata: information (1) Chordata: pictures (15213) Chordata: specimens (6829) Chordata: sounds (709)

- Subphylum Vertebrata vertebrates Vertebrata: information (1) Vertebrata: pictures (15168) Vertebrata: specimens (6827) Vertebrata: sounds (709)

- Class Aves birds Aves: information (1) Aves: pictures (7311) Aves: specimens (153) Aves: sounds (676)

- Order Procellariiformes tube-nosed seabirds Procellariiformes: pictures (48) Procellariiformes: specimens (15)

- Family Diomedeidae albatrosses Diomedeidae: pictures (27) Diomedeidae: specimens (6)

- Genus Diomedea royal and wandering albatrosses Diomedea: pictures (5) Diomedea: specimens (4)

- Species Diomedea exulans wandering albatross Diomedea exulans: information (1) Diomedea exulans: pictures (3)

To cite this page: Scopel, L. 2007. "Diomedea exulans" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed May 09, 2024 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Diomedea_exulans/

Disclaimer: The Animal Diversity Web is an educational resource written largely by and for college students . ADW doesn't cover all species in the world, nor does it include all the latest scientific information about organisms we describe. Though we edit our accounts for accuracy, we cannot guarantee all information in those accounts. While ADW staff and contributors provide references to books and websites that we believe are reputable, we cannot necessarily endorse the contents of references beyond our control.

- U-M Gateway | U-M Museum of Zoology

- U-M Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

- © 2020 Regents of the University of Michigan

- Report Error / Comment

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Grants DRL 0089283, DRL 0628151, DUE 0633095, DRL 0918590, and DUE 1122742. Additional support has come from the Marisla Foundation, UM College of Literature, Science, and the Arts, Museum of Zoology, and Information and Technology Services.

The ADW Team gratefully acknowledges their support.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Brief Communication

- Published: 31 August 2000

Oceanic respite for wandering albatrosses

- Henri Weimerskirch 2 , 1 &

- Rory P. Wilson 3

Nature volume 406 , pages 955–956 ( 2000 ) Cite this article

838 Accesses

107 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

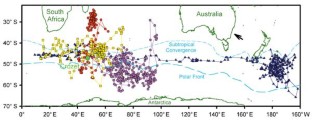

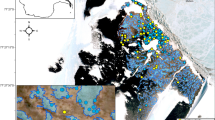

Birds taking time off from breeding head for their favourite long-haul destinations.

What oceanic seabirds do outside their breeding periods is something of a mystery, although altogether these “sabbaticals’ add up to more than half of their lifetime and are probably a key feature of their life history. Here we use geolocation systems based on light-intensity measurements to show that during these periods wandering albatrosses ( Diomedea exulans ) leave the foraging grounds that they frequent while breeding for specific, individual oceanic sectors and spend the rest of the year there — each bird probably returns to the same area throughout its life. This discovery of individual home-range preferences outside the breeding season has important implications for the conservation of albatrosses threatened by the development of longline fisheries.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Flexibility of little auks foraging in various oceanographic features in a changing Arctic

At-sea distribution patterns of the Peruvian diving petrel Pelecanoides garnotii during breeding and non-breeding seasons

Thermal vulnerability of sea turtle foraging grounds around the globe

Weimerskirch, H., Jouventin, P., Mougin, J. L., Stahl, J. C. & Van Beveren, M. Emu 85 , 22–23 (1985).

Article Google Scholar

Murphy, R. C. Oceanic Birds of South America (Macmillan, New York, 1936).

Google Scholar

Nicholls, D. G., Murray, M. D., Butcher, E. & Moors, P. Emu 97 , 240–244 ( 1997).

Jouventin, P. & Weimerskirch, H. Nature 343 , 746–748 (1990).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Brothers, N. P. Biol. Conserv. 55 , 255–268 (1991).

Wilson, R. P., Ducamp, J. J., Rees, G., Culik, B. M. & Niekamp, K. in Wildlife Telemetry: Remote Monitoring and Tracking of Animals (eds Priede, I. M. & Swift, S. M) 131– 134 (Horward, Chichester, 1992).

Hill, R. D. in Elephant Seals: Population Ecology, Behavior, and Physiology (eds Le Boeuf, B. J. & Laws, R. M.) 227–236 (Univ. California Press, Berkeley, 1994).

Welch, D. W. & Eveson, J. P. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 56 , 1317–1327 (1999).

Weimerskirch, H., Doncaster, P. & Cuénot-Chaillet, F. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 255 , 91–97 (1994).

Robertson, G. & Gales, R. Albatross, Biology and Conservation (Beatty, Chipping Norton, Australia, 1993).

Weimerskirch, H., Brothers, N. P. & Jouventin, P. Biol. Conserv. 79 , 257– 270 (1997).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

CEBC-CNRS, Villiers en Bois, 79360, France

Henri Weimerskirch

Institut Français pour la Recherche et la Technologie Polaire, Plouzane, 29280, France

Institüt für Meereskunde, Kiel, D-24105, Germany

Rory P. Wilson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Weimerskirch, H., Wilson, R. Oceanic respite for wandering albatrosses. Nature 406 , 955–956 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35023068

Download citation

Issue Date : 31 August 2000

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/35023068

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Did the animal move a cross-wavelet approach to geolocation data reveals year-round whereabouts of a resident seabird.

- Karine Delord

- Sophie Lanco-Bertrand

Marine Biology (2021)

Individual Chemical Profiles in the Leach’s Storm-Petrel

- Sarah L. Jennings

- Susan E. Ebeler

Journal of Chemical Ecology (2020)

Extensive use of the high seas by Vulnerable Fiordland Penguins across non-breeding stages

- Jean-Baptiste Thiebot

- Charles-André Bost

- Susan M. Waugh

Journal of Ornithology (2020)

Review of dynamic soaring: technical aspects, nonlinear modeling perspectives and future directions

- Sameh A. Eisa

- Adnan Maqsood

Nonlinear Dynamics (2018)

Factors affecting the importance of myctophids in the diet of the world’s seabirds

- Yutaka Watanuki

Marine Biology (2018)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Origin, age, sex and breeding status of wandering albatrosses ( Diomedea exulans ), northern ( Macronectes halli ) and southern giant petrels ( Macronectes giganteus ) attending demersal longliners in Falkland Islands and Scotia Ridge waters, 2001–2005

- Original Paper

- Published: 11 August 2006

- Volume 30 , pages 359–368, ( 2007 )

Cite this article

- Helen Otley 1 ,

- Tim Reid 2 ,

- Richard Phillips 3 ,

- Andy Wood 3 ,

- Ben Phalan 3 &

- Isaac Forster 3

222 Accesses

19 Citations

Explore all metrics

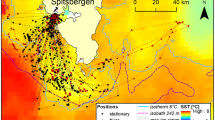

A total of 547 sightings of 291 banded wandering albatrosses Diomedea exulans and 21 sightings of 14 banded giant petrels Macronectes spp. were made from toothfish longliners operating on the southern Patagonian Shelf during 2001–2005. This included 25% of the wandering albatrosses with Darvic bands that bred at Bird Island (South Georgia) during this period. Thirteen of the northern Macronectes halli and southern giant petrels Macronectes giganteus had been banded at South Georgia, and there was one sighting of a southern giant petrel from Argentina. Male and female wandering albatrosses of all age classes except young birds (<15 years old) were equally likely to attend longline vessels. Most sightings of all age classes were made during the incubation period and fewest during the brood period. Eighty-six percent of birds sighted had bred at least once before, with half currently breeding and half on sabbatical (i.e. between breeding attempts). Almost half of the wandering albatrosses were sighted on more than one occasion. The data confirms that the southern Patagonian shelf is an important foraging area for wandering albatrosses and northern and southern giant petrels, and that some individuals show consistent associations in multiple years with longline vessels fishing in the region.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Fishing and recording dead fish by citizen scientists contribute valuable data on south American ray-finned fish diversity

Life-history, movement, and habitat use of scylla serrata (decapoda, portunidae): current knowledge and future challenges.

I need some space: solitary nesting Adélie penguins demonstrate an alternative breeding strategy at Cape Crozier

Catry P, Phillips RA, Hamer KC, Ratcliffe N, Furness RW (1998) The incidence of non-breeding by adult great skuas and parasitic jaegers from Foula, Shetland. Condor 100:448–455

Google Scholar

Chastel O, Weimerskirch H, Jouventin P (1995) Influence of body condition on reproductive decision and reproductive success in the blue petrel. Auk 112:964–972

Cooper J, Weimerskirch H (2003) Exchange of the Wandering albatross Diomedea exulans between the Prince Edward and Crozet Islands: implications for conservation. Afr J Mar Sci 25:519–523

Copello S, Quintana F, Rabufetti (2005) Dispersión de juveniles de petrel gigante del sur, Macronectes giganteus , anillados en colonias del norte de Patagonia. XI Reuníón Argentina de Ornotología. 7–10 September 2005, Buenos Aires

Croxall JP, Gales R (1998) An assessment of the conservation status of albatrosses. In: Robertson G, Gales R (eds) Albatross biology and conservation. Surrey Beatty and Sons, Chipping Norton, pp 46–65

Croxall JP, Wood AG (2002) The importance of the Patagonian Shelf for top predator species breeding at South Georgia. Aquat Conserv Mar Freshw Ecosyst 12:101–118

Article Google Scholar

Croxall JP, Prince PA, Rothery P, Wood AG (1998) Population changes in albatrosses at South Georgia. In: Robertson G, Gales R (eds) Albatross biology and conservation. Surrey Beatty and Sons, Chipping Norton, pp 69–83

Croxall JP, Black AD, Wood AG (1999) Age, sex and status of wandering albatrosses Diomedea exulans L . in Falkland Islands waters. Antarct Sci 11:150–156

de la Mare WK, Kerry KR (1994) Population dynamics of the wandering albatross ( Diomedea exulans ) on Macquarie Island and the effects of mortality from longline fishing. Polar Biol 14:231–241

Forero MG, Bortolloti, Hobson KA, Donazar JA, Bertelloti M, Blanco G (2004) High trophic overlap within the seabird community of Argentinean Patagonia: a multiscale approach. J Anim Ecol 73:789–801

Freeman AND, Wilson KJ, Nicholls DG (2001) Westland petrels and the hoki fishery: determining co-occurrence using satellite telemetry. Emu 101:47–56

Gales R, Brothers N, Reid T (1998) Seabird mortality in the Japanese tuna longline fishery around Australia. Biol Conserv 86:37–56

González-Solis J, Croxall JP, Wood AG (2000) Foraging partitioning between giant petrels Macronectes spp. and its relationship with breeding population changes at Bird Island, South Georgia. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 204:279–288

Hunter S (1983) The food and feeding ecology of the giant petrels Macronectes halli and M. giganteus at South Georgia. J Zool Lond 200:521–538

Hunter S (1984) Breeding biology and population dynamics of giant petrels Macronectes at South Georgia (Aves: Procellariiformes). J Zool Lond 203:441–460

Laptikhovsky V, Brickle P (2005) The Patagonian toothfish fishery in Falkland Islands’ waters. Fish Res 74:11–23

Nicholls DG, Murray D, Battam H, Robertson G, Moors P, Butcher E, Hildebrandt M (1995) Satellite tracking of the wandering albatross Diomedea exulans around Australia and in the Indian Ocean. Emu 95:223–230

Nicholls DG, Robertson CJR, Prince PA, Murray MD, Walker KJ, Elliott GP (2002) Foraging niches of three Diomedea albatrosses. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 231:269–277

Otley H (2005) Seabird attendance at Patagonian toothfish longliners in the Falkland Islands over three years. Falkland Islands Fisheries Department, Stanley, Falkland Islands

Phillips RA, Silk JRD, Croxall JP, Afanasyev V, Bennett VJ (2005) Summer distribution and migration of nonbreeding albatrosses: individual consistencies and implications for conservation. Ecology 86:2386–2396

Pickering SPC (1989) Attendance patterns and behaviour in relation to experience and pair-bond formation in the wandering albatross Diomedea exulans at South Georgia. Ibis 131:183–195

Poncet S, Robertson G, Phillips RA, Lawton K, Phalan B, Trathan PN, Croxall JP (2006) Status and distribution of wandering, black-browed and grey-headed albatrosses breeding at South Georgia. Polar Biol (online first)

Prince PA, Croxall JP, Trathan PN, Wood AG (1998) The pelagic distribution of South Georgia albatrosses and their relationships with fisheries. In: Robertson G, Gales R (eds) Albatross biology and conservation. Surrey Beatty and Sons, Chipping Norton, pp 137–167

Quintana F, Dell’Arciprete OP (2002) Foraging grounds of southern giant petrels ( Macronectes giganteus ) on the Patagonian shelf. Polar Biol 25:159–161

Reid TA, Sullivan BJ (2004) Longliners, black-browed albatross mortality and bait scavenging in Falkland Island waters: what is the relationship? Polar Biol 27:131–139

Reid TA, Sullivan BJ, Pompert J, Enticott JW, Black AD (2004) Seabird mortality associated with Patagonian toothfish ( Dissostichus eleginoides ). Emu 104:317–325

Ryan PG, Boix-Hinzen C (1999) Consistent male-biased seabird mortality in the Patagonian toothfish longline fishery. Auk 116:851–854

Sullivan BJ, Reid TA, Bugoni L (2006) Seabird mortality on factory trawlers in the Falkland Islands and beyond. Biol Conserv 131:495–504

Thompson KR, Riddy MD (1995) Utilization of offal and discards from “finfish” trawlers around the Falkland Islands by the Black-browed albatross Diomedea melanophris . Ibis 137:198–206

Tickell WLN (1968) The biology of the great albatrosses, Diomedea exulans and Diomedea epomophora . In: Austin OL Jr (ed) Antarctic bird studies. American Geophysical Union, Washington, pp 1–55

Tickell WLN (2000) Albatrosses. Pica Press, East Sussex

Votier SC, Furness RW, Bearhop S, Crane JE, Caldow RWG, Catry P, Ensor K, Hamer KC, Hudson AV, Kalmbach E, Klomp NI, Pfeiffer P, Phillips RA, Prieto I, Thompson DR (2004) Changes in fisheries discard rates and seabird communities. Nature 427:727–730

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Waugh S, Filippi D, Fukuda A, Suzuki M, Higuchi H, Setiawan A, Davis L (2005) Foraging of royal albatrosses, Diomedea epomophora , from the Otago Peninsula and its relationships to fisheries. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 62:1410–1421

White RW, Gillon KW, Black AD, Reid JB (2002) The distribution of seabirds and marine mammals in Falkland Islands waters. JNCC and Falklands Conservation, Peterborough

Xavier JC, Croxall JP, Trathan PN, Wood AG (2003a) Feeding strategies and diets of breeding grey-headed and wandering albatrosses at South Georgia. Mar Biol 143:221–232

Xavier JC, Croxall JP, Trathan PN, Wood AG (2003b) Interannual variation in the diets of two albatross species breeding at South Georgia: implications for breeding performance. Ibis 145:593–610

Xavier JC, Trathan PN, Croxall JP, Wood AG, Podesta G, Rodhouse PG (2004) Foraging ecology and interactions with fisheries of wandering albatrosses ( Diomedea exulans ) breeding at South Georgia. Fish Oceanogr 13:324–344

Download references

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to FIFD observers Andy Black, Ross James, Matthew Pearce and Oli Yates for their sightings, J. Pompert who supervised the FIFD observer program and Janet Silk for the figures. Flavio Quintana (Centro Nacional Patagónico, Conicet Argentina) and Fabian Rabufetti (Aves Argentinas) kindly provided information about their southern giant petrel banding program. We also express thanks to Sally Poncet for providing records of Bird Island banded albatrosses seen during the 2003/2004 South Georgia albatross census and advice on an earlier draft of this paper. A. Arkhipkin and two anonymous referees also helped to improve the manuscript. The support of the Fisheries Patrol Officers and the crew of the Fishery Patrol Vessels Dorada and Sigma for the transfer of observers were critical. H.O. wishes to thank Consolidated Fisheries Limited who provided funding for the collation of the data and to the Government of South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands for generous assistance during manuscript preparation. We thank all those who have banded wandering albatrosses and giant petrels at Bird Island since 1958.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Falkland Islands Fisheries Department, Stanley, FIQQ 1ZZ, Falkland Islands, UK

Helen Otley

Falklands Conservation, PO Box 26, Stanley, FIQQ 1ZZ, Falkland Islands, UK

British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 0ET, UK

Richard Phillips, Andy Wood, Ben Phalan & Isaac Forster

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Helen Otley .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article