- What Was The Grand Tour...

What Was the Grand Tour and Where Did People Go?

Freelance Travel and Music Writer

Nowadays, it’s so easy to pack a bag and hop on a flight or interrail across Europe’s railway at your own leisure. But what if it was known as a right of passage, made no easier by the fact that there was no such modern luxury? Welcome to the Grand Tour – and we’re not talking about Jeremy Clarkson’s TV series …

What was the grand tour all about.

The Grand Tour was a trip of Europe, typically undertaken by young men, which begun in the 17th century and went through to the mid-19th. Women over the age of 21 would occasionally partake, providing they were accompanied by a chaperone from their family. The Grand Tour was seen as an educational trip across Europe, usually starting in Dover, and would see young, wealthy travellers search for arts and culture. Though travelling was not as easy back then, mostly thanks to no rail routes like today, those on The Grand Tour would often have a healthy supply of funds in order to enjoy themselves freely.

What did travellers get up to?

Of course, in the 17th century, there was no such thing as the internet, making discovering things while sat on the other side of the world near impossible. Cultural integration was not yet fully-fledged and nothing like we experience today, so the only way to understand different ways of life was to experience them yourself. Hence why so many people set off for the Grand Tour – the ultimate trip across Europe!

Typical routes taken on the Grand Tour

Travellers (occompanied by a tutor) would often start around the South East region and head in to France, where a coach would often be rented should the party be wealthy enough. Occasionally, the coaches would need to be disassembled in order to cross difficult terrain such as the Alps.

Once passing through Calais and Paris, a typical journey would include a stop-off in Switzerland before crossing the Alps in to Northern Italy. Here’s where the wealth really comes in to play – as luggage and methods of transport would need to be dismantled and carried manually – as really rich travellers would often employ servants to carry everything for them.

Of course, Italy is a highly cultural country and famous for its art and historic buildings, so travellers would spend longer here. Turin, Florence, Rome, Pompeii and Venice would be amongst the cities visited, generally enticing those in to extended stays.

On the return leg, travellers would visit Germany and occasionally Austria, including study time at universities such as Munich, before heading to Holland and Flanders, ahead of crossing the Channel back to Dover.

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel - and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way. That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Culture Trips, Rail Trips and Private Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

Culture Trips are deeply immersive 5 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and 4-5* accommodation to look forward to at the end of each day. Our Rail Trips are our most planet-friendly itineraries that invite you to take the scenic route, relax whilst getting under the skin of a destination. Our Private Trips are fully tailored itineraries, curated by our Travel Experts specifically for you, your friends or your family.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm - and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet. That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

Guides & Tips

The best european trips for foodies.

Places to Stay

The best private trips to book for your classical studies class.

The Best Private Trips to Book in Southern Europe

The Best Places in Europe to Visit in 2024

The Best Places to Travel in August 2024

The Best Private Trips to Book in Europe

Five Places That Look Even More Beautiful Covered in Snow

The Best Rail Trips to Take in Europe

The Best Trips for Sampling Amazing Mediterranean Food

The Best Private Trips to Book With Your Support Group

The Best Places to Travel in May 2024

The Best Private Trips to Book for Your Religious Studies Class

Culture trip spring sale, save up to $1,100 on our unique small-group trips limited spots..

- Post ID: 1702695

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

What was the Grand Tour?

Find out about the travel phenomenon that became popular amongst the young nobility of England

Art, antiquity and architecture: the Grand Tour provided an opportunity to discover the cultural wonders of Europe and beyond.

Popular throughout the 18th century, this extended journey was seen as a rite of passage for mainly young, aristocratic English men.

As well as marvelling at artistic masterpieces, Grand Tourists brought back souvenirs to commemorate and display their journeys at home.

One exceptional example forms the subject of a new exhibition at the National Maritime Museum. Canaletto’s Venice Revisited brings together 24 of Canaletto’s Venetian views, commissioned in 1731 by Lord John Russell following his visit to Venice.

Find out more about this travel phenomenon – and uncover its rich cultural legacy.

Canaletto's Venice Revisited

The origins of the Grand Tour

The development of the Grand Tour dates back to the 16th century.

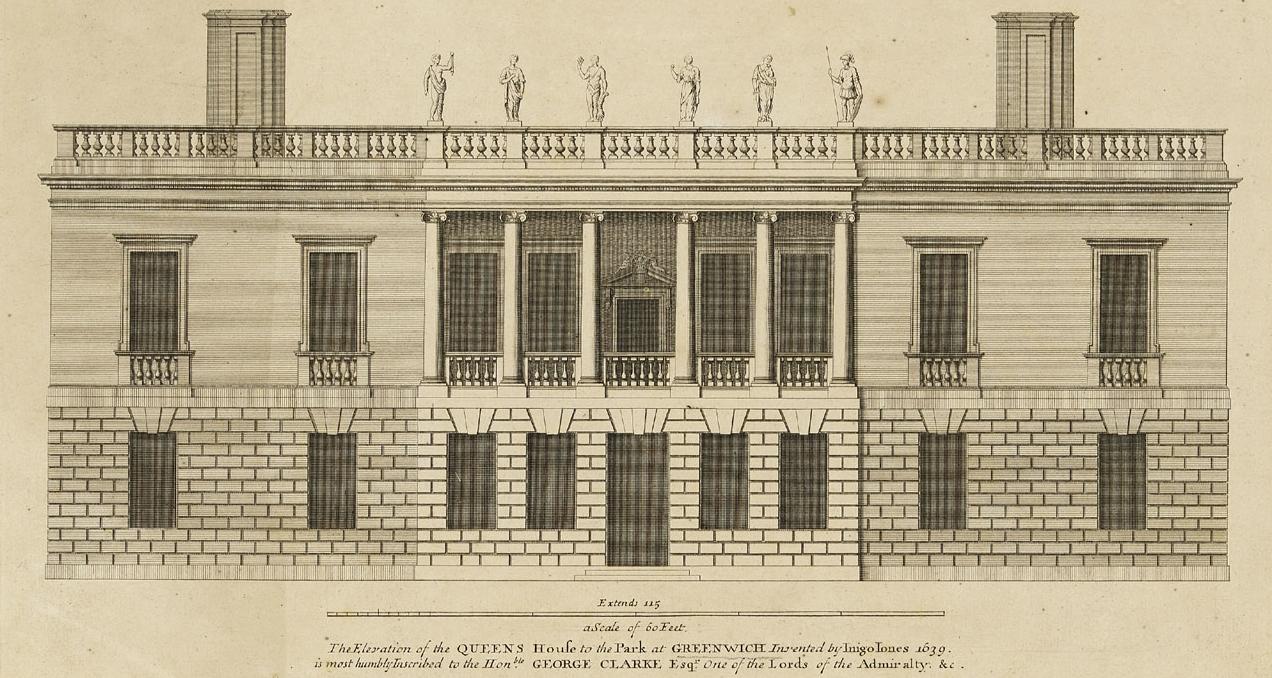

One of the earliest Grand Tourists was the architect Inigo Jones , who embarked on a tour of Italy in 1613-14 with his patron Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel.

Jones visited cities such as Parma, Venice and Rome. However, it was Naples that proved the high point of his travels.

Jones was particularly fascinated by the San Paolo Maggiore, describing the church as “one of the best things that I have ever seen.”

Jones’s time in Italy shaped his architectural style. In 1616, Jones was commissioned to design the Queen’s House in Greenwich for Queen Anne of Denmark , the wife of King James I. Completed in around 1636, the house was the first classical building in England.

The expression ‘Grand Tour’ itself comes from 17th century travel writer and Roman Catholic priest Richard Lassels, who used it in his guidebook The Voyage of Italy, published in 1670.

By the 18th century, the Grand Tour had reached its zenith. Despite Anglo-French wars in 1689-97 and 1702-13, this was a time of relative stability in Europe, which made travelling across the continent easier.

The Grand Tour route

For young English aristocrats, embarking on the Grand Tour was seen as an important rite of passage.

Accompanied by a tutor, a Grand Tourist’s route typically involved taking a ship across the English Channel before travelling in a carriage through France, stopping at Paris and other major cities.

Italy was also a popular destination thanks to the art and architecture of places such as Venice, Florence, Rome, Milan and Naples. More adventurous travellers ventured to Sicily or even sailed across to Greece. The average Grand Tour lasted for at least a year.

As Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich explains, this extended journey marked the culmination of a Grand Tourist’s education.

“The Grand Tourists would have received an education that was grounded in the Classics,” she says. “During their travels to the continent, they would have seen classical ruins and read Latin and Greek texts. The Grand Tour was also an opportunity to take in more recent culture, such as Renaissance paintings, and see contemporary artists at work.”

As well as educational opportunities, the Grand Tour was linked with independence. Places such as Venice were popular with pleasure seekers, boasting gambling houses and occasions for drinking and partying.

“On the Grand Tour, there’s a sense that travellers are gaining some of their independence and having a lesson in the ways of the world,” Gazzard explains. “For visitors to Venice, there were opportunities to behave beyond the social norms, with the masquerade and the carnival.”

Art and the Grand Tour

Bound up with the idea of independence was the need to collect souvenirs, which the Grand Tourists could display in their homes.

“The ownership of property was tied to status, so creating a material legacy was really important for the Grand Tourists in order to solidify their social standing amongst their peers,” says Gazzard. “They were looking to spend money and buy mementos to prove they went on the trip.”

The works of artists such as those of the 18th century view painter Giovanni Antonio Canal (known as Canaletto ) were especially popular with Grand Tourists. Prized for their detail, Canaletto’s artworks captured the landmarks and scenes of everyday Venetian life, from festive scenes to bustling traffic on the Grand Canal .

In 1731, Lord John Russell, the future 4th Duke of Bedford, commissioned Canaletto to create 24 Venetian views following his visit to the city.

Lord John Russell is known to have paid at least £188 for the set – over five times the annual earnings of a skilled tradesperson at the time.

“Canaletto’s work was portable and collectible,” says Gazzard. “He adopted a smaller size for his canvases so they could be rolled up and shipped easily.”

These detailed works, now part of the world famous collection at Woburn Abbey, form the centrepiece of Canaletto’s Venice Revisited at the National Maritime Museum .

Who was Canaletto?

The legacy of the Grand Tour

The start of the French Revolution in 1789 marked the end of the Grand Tour. However, its legacy is still keenly felt.

The desire to explore and learn about different places and cultures through travel continues to endure. The legacy of the Grand Tour can also be seen in the artworks and objects that adorn the walls of stately homes and museums, and the many cultural influences that travellers brought back to Britain.

Canaletto's Venice Revisited

Main image: The Piazza San Marco looking towards the Basilica San Marco and the Campanile by Canaletto . From the Woburn Abbey Collection . Canaletto painting in body copy: Regatta on Grand Canal by Canaletto From the Woburn Abbey Collection

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

What Was the Grand Tour of Europe?

Lucy Davidson

26 jan 2022, @lucejuiceluce.

In the 18th century, a ‘Grand Tour’ became a rite of passage for wealthy young men. Essentially an elaborate form of finishing school, the tradition saw aristocrats travel across Europe to take in Greek and Roman history, language and literature, art, architecture and antiquity, while a paid ‘cicerone’ acted as both a chaperone and teacher.

Grand Tours were particularly popular amongst the British from 1764-1796, owing to the swathes of travellers and painters who flocked to Europe, the large number of export licenses granted to the British from Rome and a general period of peace and prosperity in Europe.

However, this wasn’t forever: Grand Tours waned in popularity from the 1870s with the advent of accessible rail and steamship travel and the popularity of Thomas Cook’s affordable ‘Cook’s Tour’, which made mass tourism possible and traditional Grand Tours less fashionable.

Here’s the history of the Grand Tour of Europe.

Who went on the Grand Tour?

In his 1670 guidebook The Voyage of Italy , Catholic priest and travel writer Richard Lassells coined the term ‘Grand Tour’ to describe young lords travelling abroad to learn about art, culture and history. The primary demographic of Grand Tour travellers changed little over the years, though primarily upper-class men of sufficient means and rank embarked upon the journey when they had ‘come of age’ at around 21.

‘Goethe in the Roman Campagna’ by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein. Rome 1787.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Grand Tours also became fashionable for women who might be accompanied by a spinster aunt as a chaperone. Novels such as E. M. Forster’s A Room With a View reflected the role of the Grand Tour as an important part of a woman’s education and entrance into elite society.

Increasing wealth, stability and political importance led to a more broad church of characters undertaking the journey. Prolonged trips were also taken by artists, designers, collectors, art trade agents and large numbers of the educated public.

What was the route?

The Grand Tour could last anything from several months to many years, depending on an individual’s interests and finances, and tended to shift across generations. The average British tourist would start in Dover before crossing the English Channel to Ostend in Belgium or Le Havre and Calais in France. From there the traveller (and if wealthy enough, group of servants) would hire a French-speaking guide before renting or acquiring a coach that could be both sold on or disassembled. Alternatively, they would take the riverboat as far as the Alps or up the Seine to Paris .

Map of grand tour taken by William Thomas Beckford in 1780.

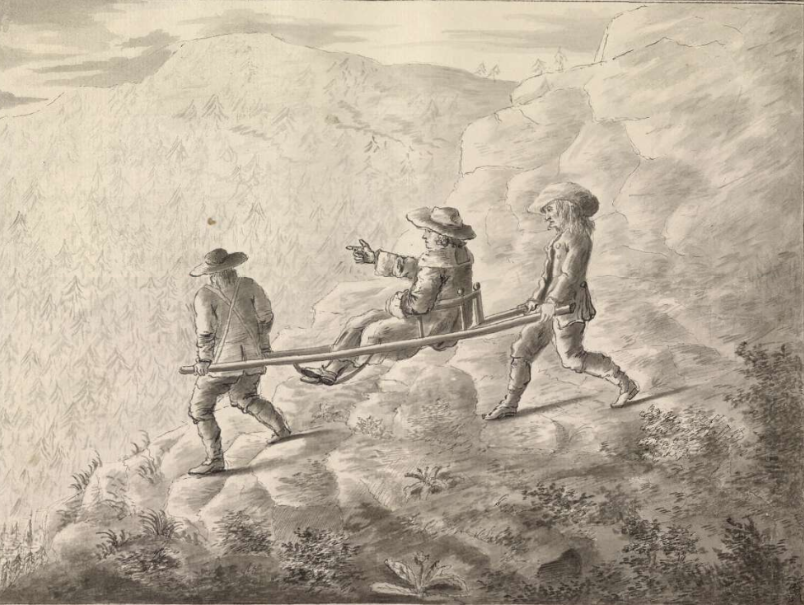

From Paris, travellers would normally cross the Alps – the particularly wealthy would be carried in a chair – with the aim of reaching festivals such as the Carnival in Venice or Holy Week in Rome. From there, Lucca, Florence, Siena and Rome or Naples were popular, as were Venice, Verona, Mantua, Bologna, Modena, Parma, Milan, Turin and Mont Cenis.

What did people do on the Grand Tour?

A Grand Tour was both an educational trip and an indulgent holiday. The primary attraction of the tour lay in its exposure of the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, such as the excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii, as well as the chance to enter fashionable and aristocratic European society.

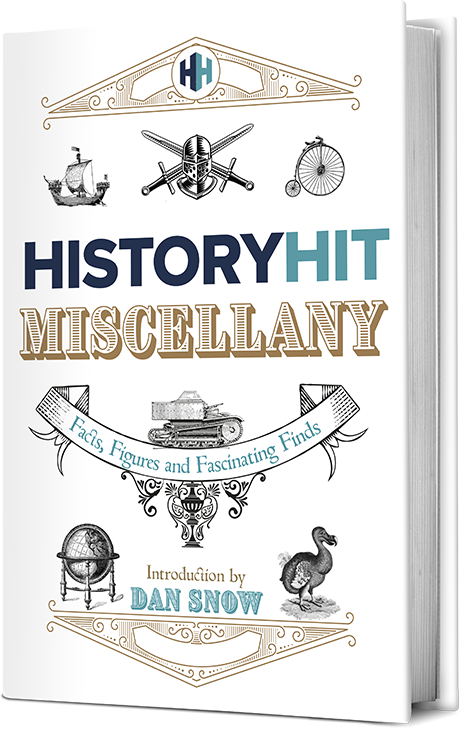

Johann Zoffany: The Gore Family with George, third Earl Cowper, c. 1775.

In addition, many accounts wrote of the sexual freedom that came with being on the continent and away from society at home. Travel abroad also provided the only opportunity to view certain works of art and potentially the only chance to hear certain music.

The antiques market also thrived as lots of Britons, in particular, took priceless antiquities from abroad back with them, or commissioned copies to be made. One of the most famous of these collectors was the 2nd Earl of Petworth, who gathered or commissioned some 200 paintings and 70 statues and busts – mainly copies of Greek originals or Greco-Roman pieces – between 1750 and 1760.

It was also fashionable to have your portrait painted towards the end of the trip. Pompeo Batoni painted over 175 portraits of travellers in Rome during the 18th century.

Others would also undertake formal study in universities, or write detailed diaries or accounts of their experiences. One of the most famous of these accounts is that of US author and humourist Mark Twain, whose satirical account of his Grand Tour in Innocents Abroad became both his best selling work in his own lifetime and one of the best-selling travel books of the age.

Why did the popularity of the Grand Tour decline?

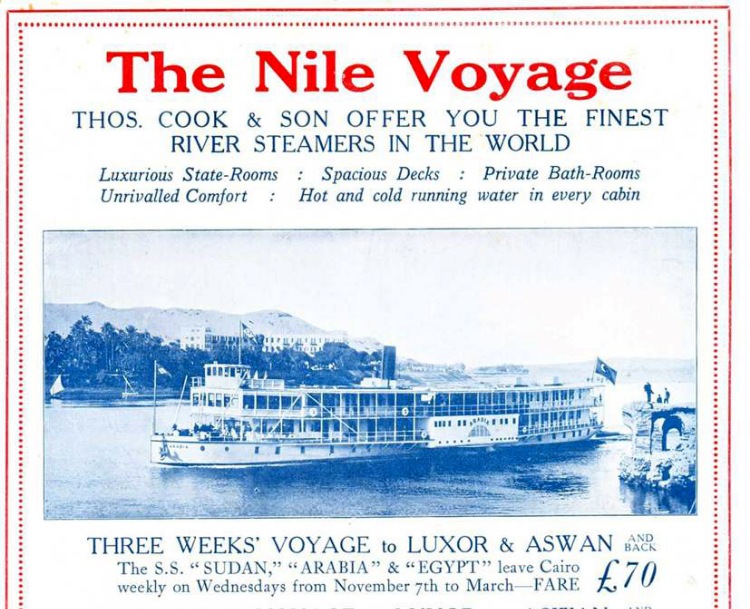

A Thomas Cook flyer from 1922 advertising cruises down the Nile. This mode of tourism has been immortalised in works such as Death on the Nile by Agatha Christie.

The popularity of the Grand Tour declined for a number of reasons. The Napoleonic Wars from 1803-1815 marked the end of the heyday of the Grand Tour, since the conflict made travel difficult at best and dangerous at worst.

The Grand Tour finally came to an end with the advent of accessible rail and steamship travel as a result of Thomas Cook’s ‘Cook’s Tour’, a byword of early mass tourism, which started in the 1870s. Cook first made mass tourism popular in Italy, with his train tickets allowing travel over a number of days and destinations. He also introduced travel-specific currencies and coupons which could be exchanged at hotels, banks and ticket agencies which made travelling easier and also stabilised the new Italian currency, the lira.

As a result of the sudden potential for mass tourism, the Grand Tour’s heyday as a rare experience reserved for the wealthy came to a close.

Can you go on a Grand Tour today?

Echoes of the Grand Tour exist today in a variety of forms. For a budget, multi-destination travel experience, interrailing is your best bet; much like Thomas Cook’s early train tickets, travel is permitted along many routes and tickets are valid for a certain number of days or stops.

For a more upmarket experience, cruising is a popular choice, transporting tourists to a number of different destinations where you can disembark to enjoy the local culture and cuisine.

Though the days of wealthy nobles enjoying exclusive travel around continental Europe and dancing with European royalty might be over, the cultural and artistic imprint of a bygone Grand Tour era is very much alive.

To plan your own Grand Tour of Europe, take a look at History Hit’s guides to the most unmissable heritage sites in Paris , Austria and, of course, Italy .

You May Also Like

Mac and Cheese in 1736? The Stories of Kensington Palace’s Servants

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

18th Century Grand Tour of Europe

The Travels of European Twenty-Somethings

Print Collector/Getty Images

- Key Figures & Milestones

- Physical Geography

- Political Geography

- Country Information

- Urban Geography

- M.A., Geography, California State University - Northridge

- B.A., Geography, University of California - Davis

The French Revolution marked the end of a spectacular period of travel and enlightenment for European youth, particularly from England. Young English elites of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries often spent two to four years touring around Europe in an effort to broaden their horizons and learn about language , architecture , geography, and culture in an experience known as the Grand Tour.

The Grand Tour, which didn't come to an end until the close of the eighteenth century, began in the sixteenth century and gained popularity during the seventeenth century. Read to find out what started this event and what the typical Tour entailed.

Origins of the Grand Tour

Privileged young graduates of sixteenth-century Europe pioneered a trend wherein they traveled across the continent in search of art and cultural experiences upon their graduation. This practice, which grew to be wildly popular, became known as the Grand Tour, a term introduced by Richard Lassels in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy . Specialty guidebooks, tour guides, and other aspects of the tourist industry were developed during this time to meet the needs of wealthy 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors as they explored the European continent.

These young, classically-educated Tourists were affluent enough to fund multiple years abroad for themselves and they took full advantage of this. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England in order to communicate with and learn from people they met in other countries. Some Tourists sought to continue their education and broaden their horizons while abroad, some were just after fun and leisurely travels, but most desired a combination of both.

Navigating Europe

A typical journey through Europe was long and winding with many stops along the way. London was commonly used as a starting point and the Tour was usually kicked off with a difficult trip across the English Channel.

Crossing the English Channel

The most common route across the English Channel, La Manche, was made from Dover to Calais, France—this is now the path of the Channel Tunnel. A trip from Dover across the Channel to Calais and finally into Paris customarily took three days. After all, crossing the wide channel was and is not easy. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Tourists risked seasickness, illness, and even shipwreck on this first leg of travel.

Compulsory Stops

Grand Tourists were primarily interested in visiting cities that were considered major centers of culture at the time, so Paris, Rome, and Venice were not to be missed. Florence and Naples were also popular destinations but were regarded as more optional than the aforementioned cities.

The average Grand Tourist traveled from city to city, usually spending weeks in smaller cities and up to several months in the three major ones. Paris, France was the most popular stop of the Grand Tour for its cultural, architectural, and political influence. It was also popular because most young British elite already spoke French, a prominent language in classical literature and other studies, and travel through and to this city was relatively easy. For many English citizens, Paris was the most impressive place visited.

Getting to Italy

From Paris, many Tourists proceeded across the Alps or took a boat on the Mediterranean Sea to get to Italy, another essential stopping point. For those who made their way across the Alps, Turin was the first Italian city they'd come to and some remained here while others simply passed through on their way to Rome or Venice.

Rome was initially the southernmost point of travel. However, when excavations of Herculaneum (1738) and Pompeii (1748) began, these two sites were added as major destinations on the Grand Tour.

Features of the Grand Tour

The vast majority of Tourists took part in similar activities during their exploration with art at the center of it all. Once a Tourist arrived at a destination, they would seek housing and settle in for anywhere from weeks to months, even years. Though certainly not an overly trying experience for most, the Grand Tour presented a unique set of challenges for travelers to overcome.

While the original purpose of the Grand Tour was educational, a great deal of time was spent on much more frivolous pursuits. Among these were drinking, gambling, and intimate encounters—some Tourists regarded their travels as an opportunity to indulge in promiscuity with little consequence. Journals and sketches that were supposed to be completed during the Tour were left blank more often than not.

Visiting French and Italian royalty as well as British diplomats was a common recreation during the Tour. The young men and women that participated wanted to return home with stories to tell and meeting famous or otherwise influential people made for great stories.

The study and collection of art became almost a nonoptional engagement for Grand Tourists. Many returned home with bounties of paintings, antiques, and handmade items from various countries. Those that could afford to purchase lavish souvenirs did so in the extreme.

Arriving in Paris, one of the first destinations for most, a Tourist would usually rent an apartment for several weeks or months. Day trips from Paris to the French countryside or to Versailles (the home of the French monarchy) were common for less wealthy travelers that couldn't pay for longer outings.

The homes of envoys were often utilized as hotels and food pantries. This annoyed envoys but there wasn't much they could do about such inconveniences caused by their citizens. Nice apartments tended to be accessible only in major cities, with harsh and dirty inns the only options in smaller ones.

Trials and Challenges

A Tourist would not carry much money on their person during their expeditions due to the risk of highway robberies. Instead, letters of credit from reputable London banks were presented at major cities of the Grand Tour in order to make purchases. In this way, tourists spent a great deal of money abroad.

Because these expenditures were made outside of England and therefore did not bolster England's economy, some English politicians were very much against the institution of the Grand Tour and did not approve of this rite of passage. This played minimally into the average person's decision to travel.

Returning to England

Upon returning to England, tourists were meant to be ready to assume the responsibilities of an aristocrat. The Grand Tour was ultimately worthwhile as it has been credited with spurring dramatic developments in British architecture and culture, but many viewed it as a waste of time during this period because many Tourists did not come home more mature than when they had left.

The French Revolution in 1789 halted the Grand Tour—in the early nineteenth century, railroads forever changed the face of tourism and foreign travel.

- Burk, Kathleen. "The Grand Tour of Europe". Gresham College, 6 Apr. 2005.

- Knowles, Rachel. “The Grand Tour.” Regency History , 30 Apr. 2013.

- Sorabella, Jean. “The Grand Tour.” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History , The Met Museum, Oct. 2003.

- A Beginner's Guide to the Enlightenment

- Architecture in France: A Guide For Travelers

- The History of Venice

- A Brief History of Rome

- A Beginner's Guide to the Renaissance

- The Best Books on Early Modern European History (1500 to 1700)

- Renaissance Architecture and Its Influence

- What Is a Monarchy?

- The Top 10 Major Cities in France

- William Turner, English Romantic Landscape Painter

- Architecture in Italy for the Lifelong Learner

- Female European Historical Figures: 1500 - 1945

- How Many Enslaved People Were Taken from Africa?

- Biography of Marco Polo, Merchant and Explorer

- Hispanic Surnames: Meanings, Origins and Naming Practices

- The Arrival and Spread of the Black Plague in Europe

The Grand Tour: Everything You Need to Know

Gokce Dyson 28 November 2022 min Read

Carl Spitzweg, Englishmen in Campania , ca. 1835, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany.

Recommended

Art Travels

On the Road: Best Traveling Paintings

Artists’ Beloved Travel Destinations as Seen Through Their Art

How to Do a 21st-Century Grand Tour According to Mr. Bacchus

Nowadays, it is very common to take a gap year before or after university studies to travel and expand your horizons. Dedicating a year or two before committing to a full-time job means you can experience different cultures, learn languages, and enjoy having a bit of fun before settling down. Back in the day, with similar objectives, many noblemen embarked on a journey across Europe before entering adulthood. It was called the Grand Tour.

The Grand Tour evolved between the 17th and 18th centuries as a custom of a traditional trip. The purpose of the Grand Tour was to provide male members of upper-class families with a formative experience. The term was first used by the Catholic priest and travel writer Richard Lassels in his guidebook The Voyage of Italy . The book came out in 1670 and described young lords traveling to Italy to see art, architecture, and antiquity. Lassels completed the Grand Tour five times during his lifetime.

In England, for example, the general view held by the aristocrats was that foreign travel completed the education of an English gentleman. However, some people were also quite skeptical about the tour. They feared the amount of money spent to make the Grand Tour possible could ruin the young nobility.

Although the Grand Tour was largely associated with English travelers, they were far from being the only ones on the road. On the contrary, wealthy families in France, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark also saw traveling as an ideal way to finish the education of their societies’ future leaders.

Itinerary of the Grand Tour

The traditional route of the Grand Tour usually began in Dover, England. Grand tourists would cross the English Channel to Le Havre in France. Upon arrival in Paris , the young men tended to hire a French-speaking guide as French was the dominant language of the elite during the 17th and 18th centuries. In Paris, they spent some time taking lessons in fencing, riding, and perhaps dancing. There, they became accustomed to the sophisticated manners of French society in courtly behavior and fashion. Paris was a crucial step in preparing for their positions to be fulfilled in government or diplomacy waiting back in England.

From there, tourists would buy transport, and if they were prosperous enough, they would hire a tutor to accompany them. The travelers would then get back on the road and cross the Alps, carried in a chair at Mont Cenis before moving on to Turin.

Italy was exceedingly the most traveled country on the Grand Tour. A Grand tourist’s list of must-see cities in Italy included Florence , Venice , and Naples . And then, there was Rome . Each Italian city offered immense importance in experiencing art and architecture, and Rome had it all.

Touring Italy

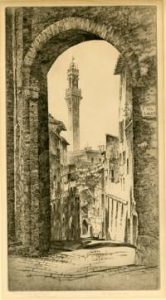

Once arriving in Italy, noblemen traveled to Florence followed by Venice, Rome, and Naples. Florence was popular for its Renaissance art, magnificent country villas, and beautiful gardens. Young aristocrats were able to gain entry to private collections where they could observe the legacy of the Medici family. Venice , on the other hand, was the party city. There was, however, a second reason to visit Venice. During their travels, grand tourists often commissioned art to take back home with them. Wealthy ones brought sketch artists along with them. Others purchased ready-made artworks instead. Giovanni Battista Piranesi created numerous prints and sketches depicting the ancient ruins in Rome. The works of the Venetian artist were popular among noblemen.

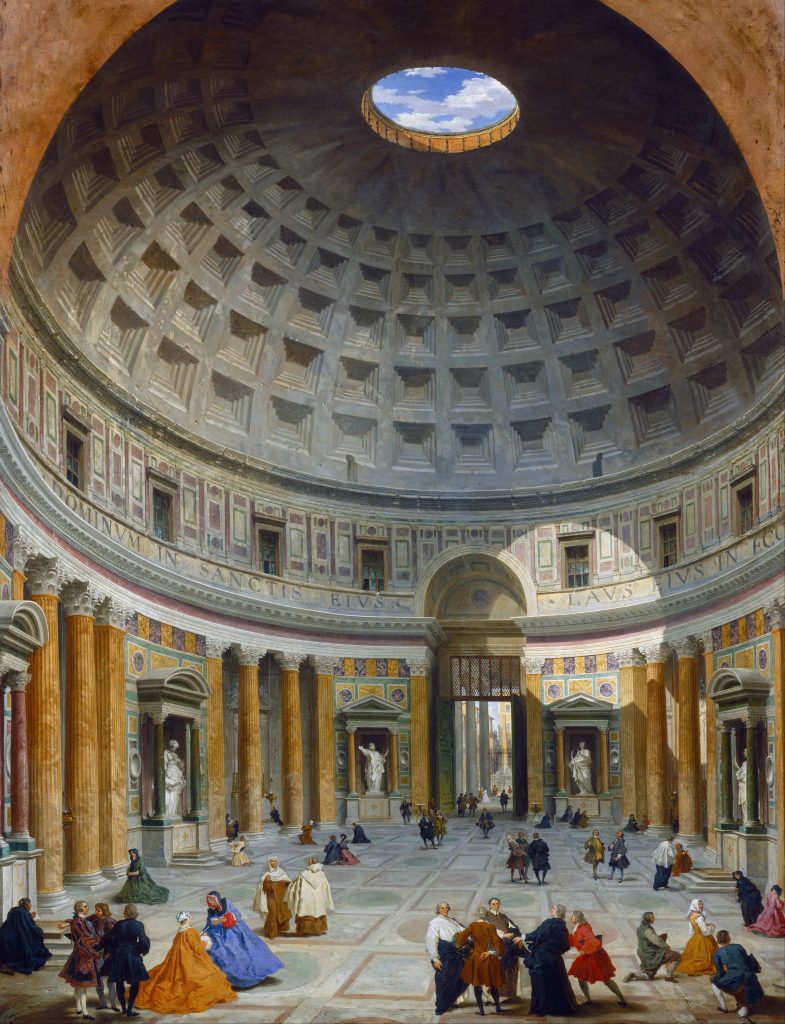

Rome was considered the ultimate stop during the Grand Tour. The city had a harmonious mixture of past and present. One could experience modern-day Baroque art and architecture and ancient ruins , dating back thousands of years at the same time. It was lauded as home to Michelangelo’s and Bernini’s most prized works. Gentlemen visited spots like the Pantheon, the Colosseum, and Porta del Popolo. William Beckford described his feelings in a letter when he was on his Grand Tour:

Shall I ever forget the sensations I experienced upon slowly descending the hills, and crossing the bridge over the Tiber; when I entered an avenue between terraces and ornamented gates of villas, which leads to the Porto del Popolo… William Beckford, letter from the Grand Tour, 1780.

The next stop on the route was Naples. When Italian authorities began excavations in Herculaneum and Pompeii in the 1730s, grand tourists flocked there to delve into the mysteries of the ancient past. Naples became a popular retreat for the British who wanted to enjoy the coastal sun. Travelers such as J. W. Goethe praised the city’s glories:

Naples is a Paradise: everyone lives in a state of intoxicated self-forgetfulness, myself included. I seem to be a completely different person whom I hardly recognize. Yesterday I thought to myself: Either you were mad before, or you are mad now. J. W. Goethe, Google Arts& Culture .

Returning home, young gentlemen crossed the Alps to the German-speaking parts of Europe and visited Innsbruck, Vienna , Dresden, and Berlin . From there, they stopped in Holland and Flanders before returning to England.

With the introduction of steam railways in Europe around 1825, travel became safer, cheaper, and easier to undertake. The Grand Tour custom continued; however, it was not limited to the members of wealthy families. During the 19th century, many educated men had undertaken the Grand Tour. It also became more popular for women to travel across Europe with chaperones. A Room with A View, written by English novelist E. M. Forster, tells the story of a young woman who embarks on a journey to Italy in the 1900s.

Legacy of the Grand Tour

Grand tourists would return with crates full of books, oil paintings, medals, coins, and antique artifacts to be displayed in libraries, cabinets, drawing rooms, and galleries built for that purpose. The marble sarcophagus shown above was brought back from Italy to England by the third duke of Beaufort who found this item during his Grand Tour stop in Pompeii. Impressed by the European art academies on his Grand Tour, Joshua Reynolds founded the Royal Academy of Arts in London upon his return in 1768. The Grand Tour inspired many travelers to take a greater interest in ancient art. The British School in Rome was established to learn more about the Roman ruins and it still exists today.

Get your daily dose of art

Click and follow us on Google News to stay updated all the time

We love art history and writing about it. Your support helps us to sustain DailyArt Magazine and keep it running.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!

Gokce Dyson

Based in Canterbury, Gokce holds a bachelor's degree in History and Archaeological Studies and a master's degree in Museum and Gallery Studies. She firmly believes that art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time. If Gokce is not tucked into a cosy corner with a medieval history book, she can be found spending her evenings doing jigsaw puzzles.

Top 5 Artsy Travel Destinations in 2024 Through Paintings

We suggest you a selection of the best tourist destinations and festivals by the hand of great artists!

Andra Patricia Ritisan 11 March 2024

Art Travels: Golden Temple of Amritsar

Nestled in the city of Amritsar in Northwestern India is the iconic Harmandir Sahib or Darbar Sahib, better known as the Golden Temple. This sublime...

Maya M. Tola 8 January 2024

Art and Sports: En Route to the Paris 2024 Olympics

The forthcoming Paris 2024 Summer Olympics will bridge the worlds of art and sport, with equestrian competitions at the Palace of Versailles, fencing...

Ledys Chemin 9 April 2024

10 Masterpieces You Need To See in London

London is a city full of masterpieces. It is not only one of the biggest art hubs but also one of the most multicultural places in the entire world.

Sandra Juszczyk 23 February 2024

Never miss DailyArt Magazine's stories. Sign up and get your dose of art history delivered straight to your inbox!

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The grand tour.

Marble sarcophagus with the Triumph of Dionysos and the Seasons

Piazza San Marco

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal)

Autre Vue Particulière de Paris depuis Nôtre Dame, Jusques au Pont de la Tournelle

Jacques Rigaud

Imaginary View of Venice, houses at left with figures on terraces, a domed church at center in the background, boats and boat-sheds below, and a seated man observing from a wall at right in the foreground, from 'Views' (Vedute altre prese da i luoghi altre ideate da Antonio Canal)

The Piazza del Popolo (Veduta della Piazza del Popolo), from "Vedute di Roma"

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Vue de la Grande Façade du Vieux Louvre

View of St. Peter's and the Vatican from the Janiculum

Richard Wilson

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768)

Anton Raphael Mengs

Modern Rome

Giovanni Paolo Panini

Ancient Rome

Portrait of a Young Man

Pompeo Batoni

Gardens of the Villa d'Este at Tivoli

Charles Joseph Natoire

Veduta dell'Anfiteatro Flavio detto il Colosseo, from: 'Vedute di Roma' (Views of Rome)

View of the Villa Lante on the Janiculum in Rome

John Robert Cozens

The Girandola at the Castel Sant'Angelo

Designed and hand colored by Louis Jean Desprez

Dining room from Lansdowne House

After a design by Robert Adam

The Burial of Punchinello

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo

Portland vase

Josiah Wedgwood and Sons

Jean Sorabella Independent Scholar

October 2003

Beginning in the late sixteenth century, it became fashionable for young aristocrats to visit Paris, Venice, Florence, and above all Rome, as the culmination of their classical education. Thus was born the idea of the Grand Tour, a practice that introduced Englishmen, Germans, Scandinavians, and also Americans to the art and culture of France and Italy for the next 300 years. Travel was arduous and costly throughout the period, possible only for a privileged class—the same that produced gentleman scientists, authors, antiquaries, and patrons of the arts.

The Objectives of the Grand Tour The Grand Tourist was typically a young man with a thorough grounding in Greek and Latin literature as well as some leisure time, some means, and some interest in art. The German traveler Johann Joachim Winckelmann pioneered the field of art history with his comprehensive study of Greek and Roman sculpture ; he was portrayed by his friend Anton Raphael Mengs at the beginning of his long residence in Rome ( 48.141 ). Most Grand Tourists, however, stayed for briefer periods and set out with less scholarly intentions, accompanied by a teacher or guardian, and expected to return home with souvenirs of their travels as well as an understanding of art and architecture formed by exposure to great masterpieces.

London was a frequent starting point for Grand Tourists, and Paris a compulsory destination; many traveled to the Netherlands, some to Switzerland and Germany, and a very few adventurers to Spain, Greece, or Turkey. The essential place to visit, however, was Italy. The British traveler Charles Thompson spoke for many Grand Tourists when in 1744 he described himself as “being impatiently desirous of viewing a country so famous in history, which once gave laws to the world; which is at present the greatest school of music and painting, contains the noblest productions of statuary and architecture, and abounds with cabinets of rarities , and collections of all kinds of antiquities.” Within Italy, the great focus was Rome, whose ancient ruins and more recent achievements were shown to every Grand Tourist. Panini’s Ancient Rome ( 52.63.1 ) and Modern Rome ( 52.63.2 ) represent the sights most prized, including celebrated Greco-Roman statues and views of famous ruins, fountains, and churches. Since there were few museums anywhere in Europe before the close of the eighteenth century, Grand Tourists often saw paintings and sculptures by gaining admission to private collections, and many were eager to acquire examples of Greco-Roman and Italian art for their own collections. In England, where architecture was increasingly seen as an aristocratic pursuit, noblemen often applied what they learned from the villas of Palladio in the Veneto and the evocative ruins of Rome to their own country houses and gardens .

The Grand Tour and the Arts Many artists benefited from the patronage of Grand Tourists eager to procure mementos of their travels. Pompeo Batoni painted portraits of aristocrats in Rome surrounded by classical staffage ( 03.37.1 ), and many travelers bought Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s prints of Roman views, including ancient structures like the Colosseum ( 59.570.426 ) and more recent monuments like the Piazza del Popolo ( 37.45.3[49] ), the dazzling Baroque entryway to Rome. Some Grand Tourists invited artists from home to accompany them throughout their travels, making views specific to their own itineraries; the British artist Richard Wilson, for example, made drawings of Italian places while traveling with the earl of Dartmouth in the mid-eighteenth century ( 1972.118.294 ).

Classical taste and an interest in exotic customs shaped travelers’ itineraries as well as their reactions. Gothic buildings , not much esteemed before the late eighteenth century, were seldom cause for long excursions, while monuments of Greco-Roman antiquity, the Italian Renaissance, and the classical Baroque tradition received praise and admiration. Jacques Rigaud’s views of Paris were well suited to the interests of Grand Tourists, displaying, for example, the architectural grandeur of the Louvre, still a royal palace, and the bustle of life along the Seine ( 53.600.1191 ; 53.600.1175 ). Canaletto’s views of Venice ( 1973.634 ; 1988.162 ) were much prized, and other works appealed to Northern travelers’ interest in exceptional fêtes and customs: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo ‘s Burial of Punchinello ( 1975.1.473 ), for instance, is peopled with characters from the Venetian carnival, and a print by Francesco Piranesi and Louis Jean Desprez depicts the Girandola, a spectacular fireworks display held at the Castel Sant’Angelo ( 69.510 ).

The Grand Tour and Neoclassical Taste The Grand Tour gave concrete form to northern Europeans’ ideas about the Greco-Roman world and helped foster Neoclassical ideals . The most ambitious tourists visited excavations at such sites as Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Tivoli, and purchased antiquities to decorate their homes. The third duke of Beaufort brought from Rome the third-century work named the Badminton Sarcophagus ( 55.11.5 ) after the house where he proudly installed it in Gloucestershire. The dining rooms of Robert Adam’s interiors typically incorporated classical statuary; the nine lifesized figures set in niches in the Lansdowne dining room ( 32.12 ) were among the many antiquities acquired by the second earl of Shelburne, whose collecting activities accelerated after 1771, when he visited Italy and met Gavin Hamilton, a noted antiquary and one of the first dealers to take an interest in Attic ceramics, then known as “Etruscan vases.” Early entrepreneurs recognized opportunities created by the culture of the Grand Tour: when the second duchess of Portland obtained a Roman cameo glass vase in a much-publicized sale, Josiah Wedgwood profited from the manufacture of jasper reproductions ( 94.4.172 ).

Sorabella, Jean. “The Grand Tour.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grtr/hd_grtr.htm (October 2003)

Further Reading

Black, Jeremy. The British and the Grand Tour . London: Croom Helm, 1985.

Black, Jeremy. Italy and the Grand Tour . New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Black, Jeremy. France and the Grand Tour . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

Haskell, Francis, and Nicholas Penny. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900 . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981.

Wilton, Andrew, and Ilaria Bignamini, eds. The Grand Tour: The Lure of Italy in the Eighteenth Century . Exhibition catalogue. London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 1996.

Additional Essays by Jean Sorabella

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Pilgrimage in Medieval Europe .” (April 2011)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe .” (August 2007)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Venetian Color and Florentine Design .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Art of the Roman Provinces, 1–500 A.D. .” (May 2010)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Baroque and Later Art .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Nude in Western Art and Its Beginnings in Antiquity .” (January 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe .” (originally published October 2001, last revised March 2013)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Interior Design in England, 1600–1800 .” (October 2003)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Vikings (780–1100) .” (October 2002)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Painting the Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Italy .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Birth and Infancy of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Crucifixion and Passion of Christ in Italian Painting .” (June 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Carolingian Art .” (December 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Ottonian Art .” (September 2008)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Ballet .” (October 2004)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ Baroque Rome .” (October 2003)

- Sorabella, Jean. “ The Opera .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- American Neoclassical Sculptors Abroad

- Baroque Rome

- The Idea and Invention of the Villa

- Neoclassicism

- The Rediscovery of Classical Antiquity

- Antonio Canova (1757–1822)

- Architecture in Renaissance Italy

- Athenian Vase Painting: Black- and Red-Figure Techniques

- The Augustan Villa at Boscotrecase

- Collecting for the Kunstkammer

- Commedia dell’arte

- The Eighteenth-Century Pastel Portrait

- Exoticism in the Decorative Arts

- Gardens in the French Renaissance

- Gardens of Western Europe, 1600–1800

- George Inness (1825–1894)

- Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778)

- Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770)

- Images of Antiquity in Limoges Enamels in the French Renaissance

- James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

- Joachim Tielke (1641–1719)

- John Frederick Kensett (1816–1872)

- Photographers in Egypt

- The Printed Image in the West: Etching

- Roman Copies of Greek Statues

- Theater and Amphitheater in the Roman World

- Anatolia and the Caucasus, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Balkan Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- France, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- The United States, 1600–1800 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1600–1800 A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- 18th Century A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- Ancient Roman Art

- Baroque Art

- Central Europe

- Central Italy

- Classical Ruins

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Greek and Roman Mythology

- The Netherlands

- Palladianism

- Period Room

- Southern Italy

- Switzerland

Artist or Maker

- Adam, Robert

- Batoni, Pompeo

- Cozens, John Robert

- Desprez, Louis Jean

- Mengs, Anton Raphael

- Natoire, Charles Joseph

- Panini, Giovanni Paolo

- Permoser, Balthasar

- Piranesi, Francesco

- Piranesi, Giovanni Battista

- Rigaud, Jacques

- Tiepolo, Giovanni Battista

- Tiepolo, Giovanni Domenico

- Wedgwood, Josiah

- Wilson, Richard

Online Features

- Connections: “Flux” by Annie Labatt

- Connections: “Genoa” by Xavier Salomon

The Grand Tour

Englishmen abroad.

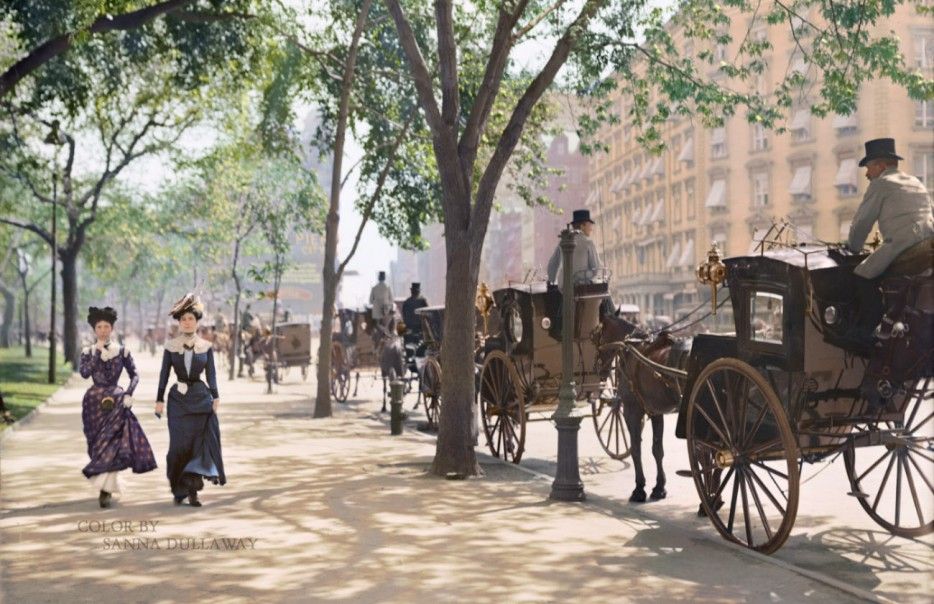

At its height, from around 1660–1820, the Grand Tour was considered to be the best way to complete a gentleman’s education. After leaving school or university, young noblemen from northern Europe left for France to start the tour.

After acquiring a coach in Calais, they would ride on to Paris – their first major stop. From there they would head south to Italy or Spain, carting all their possessions and servants with them.

Their most popular destinations were the great towns and cities of the Renaissance, along with the remains of ancient Roman and Greek civilisation.

Their souvenirs were rather more durable than holiday snaps, replica Eiffel Towers or t-shirts – they filled crates with paintings, sculptures and fine clothes.

Travel was somewhat more of an ordeal than today (even accounting for the worst airport queues and hold-ups). However rich these young men were, there was no hot shower after a day on the road, no credit card to get them out of a tight spot, and no mobile phone to ring people for help.

Furthermore transport was slow. Instead of taking a 12-month trip, some went away for many years. Most went for at least two, spending months in essential spots along the way.

The plan was to set young noblemen up to manage their estates, furnish their houses and prepare for conversation in polite society. But did the Grand Tour turn them into gentlemen? Sometimes a taste for vice got in the way.

Next: A moral education

The Grand Tour in the 19th Century: A Journey Through Elegance and Enlightenment

Welcome to my blog, 19th Century ! In this article, we will delve into the opulent world of the grand tour in the 19th century . Embark on a journey through Europe’s most magnificent cities, immersed in a cultural adventure that defined an era . Join me as we explore the elegance, extravagance, and allure of this iconic 19th-century tradition.

Table of Contents

The Grand Tour: Exploring the World in the 19th Century

The Grand Tour: Exploring the World in the 19th Century was a cultural phenomenon that emerged during this period. The Grand Tour was a trip undertaken by young European aristocrats, primarily from Britain, as part of their education and socialization. It involved traveling across Europe, particularly to cities such as Paris, Rome, Florence, and Venice, to experience art, architecture, literature, and culture firsthand.

The 19th century was a time of great exploration and discovery, and the Grand Tour provided an opportunity for affluent individuals to expand their horizons. It allowed them to immerse themselves in different societies, languages, and customs, thus broadening their understanding of the world.

Through the Grand Tour, these young travelers visited important historical sites, attended cultural events, and met influential figures, including artists, scholars, and politicians. They collected art and antiquities, which they later brought back to their homes, thereby influencing the cultural tastes and trends of the time.

Moreover, the Grand Tour played a significant role in the development of tourism as we know it today. It led to the establishment of luxury hotels, guidebooks, and travel agencies catering to the needs of these affluent travelers.

Overall, the Grand Tour was an essential aspect of the 19th-century society, shaping the cultural exchange and exploration of the time. It had a lasting impact on both the individuals who embarked on these journeys and the wider society .

FOR SALE: 1900 Gilded Age Mansion

The biggest shocks and surprises on the grand tour, what did the grand tour entail during the 19th century.

The Grand Tour was a traditional journey undertaken by young aristocrats and wealthy individuals during the 18th and 19th centuries. It was an educational and cultural pilgrimage that typically lasted several months or even years. The tour primarily involved traveling through Europe, especially Italy, but could also include other destinations like France, Germany, and Greece.

During the 19th century , the Grand Tour became even more popular and accessible due to advancements in transportation such as steamships and railways. It was seen as an essential part of a young person’s education, providing them with exposure to different cultures, art, architecture, and history.

The typical itinerary of the Grand Tour varied, but it often included stops in major cities and cultural centers like Paris, Rome, Florence, Venice, and Athens. These destinations offered an opportunity to visit prominent museums, archaeological sites, and historical landmarks. Visiting famous art collections, attending performances at renowned theaters, and participating in social events were also important components of the journey.

During their travels, tourists would hire local guides, often called “cicerones,” who would provide them with insights into the local culture and history. These guides would accompany the tourists on visits to famous landmarks, explaining their significance and enhancing the overall experience.

The Grand Tour also had a social aspect, as it allowed young individuals to network and forge connections with fellow aristocrats and influential people. They would attend social gatherings, parties, and balls, which served as opportunities to meet potential partners and discuss matters of mutual interest.

Overall, the Grand Tour was a transformative experience for those who undertook it. It broadened their horizons, refined their tastes, and contributed to their personal growth and cultural enrichment. It also played a significant role in shaping European cultural attitudes, as tourists brought back ideas, art, and fashion trends from their journeys, influencing the societies they came from.

What was the significance of the Grand Tour and why was it important?

The Grand Tour held great significance in the 19th century as it was an important rite of passage for young upper-class European men. It was a traditional journey undertaken by wealthy individuals from Western Europe to explore the cultural and historical highlights of the continent.

The Grand Tour was important for several reasons:

1. Education and Cultural Enlightenment: The primary purpose of the Grand Tour was to provide young men with a comprehensive education that went beyond academic studies. They were exposed to the arts, literature, architecture, history, and classical languages. This exposure to different cultures and ideas broadened their knowledge and refined their tastes.

2. Social and Networking Opportunities: The Grand Tour served as a social and networking platform for young men to connect with fellow aristocrats, intellectuals, and influential people they encountered along their journey. Building connections and alliances were crucial for their future roles in society, politics, and business.

3. Cultivating Maturity and Worldliness: By embarking on the Grand Tour, young men were exposed to diverse landscapes, languages, and customs. This experience helped them develop a sense of maturity and worldly sophistication, enabling them to better navigate society upon their return. They were expected to gain an understanding of other cultures and showcase their refined manners and knowledge acquired during the journey.

4. Collecting Art and Cultural Artefacts: The Grand Tour often involved acquiring art, antiquities, and cultural artifacts. Young men collected these treasures as a way to display their wealth, taste, and knowledge. These collections would not only embellish their own residences but also contribute to the development of museums and private collections across Europe.

5. Prestige and Status: Undertaking the Grand Tour was seen as a mark of prestige and status in society. It demonstrated one’s wealth, social standing, and commitment to personal growth. Completing a successful Grand Tour could enhance one’s reputation and open doors to greater opportunities and associations.

The Grand Tour played a significant role in the 19th century by providing young upper-class men with a well-rounded education, networking opportunities, and a chance to cultivate maturity and sophistication. It also served as a display of status and prestige within society. The cultural impact of the Grand Tour can still be seen today through the artworks and cultural artifacts collected during these journeys.

What is the history of the grand tour?

The Grand Tour was a form of educational travel that became popular amongst the aristocracy and upper class in the 18th and 19th centuries. It originated in England and involved young men from wealthy families embarking on a journey across Europe to gain cultural, historical, and social experiences.

The primary purpose of the Grand Tour was to complete one’s education by exposing oneself to the art, architecture, history, and literature of different European countries. It was often viewed as a finishing touch to a formal education and provided young men with an opportunity to refine their manners and knowledge of foreign languages.

The journey typically lasted several months to a year and would involve visiting major cities and cultural centers such as Paris, Rome, Venice, and Florence. Participants would hire guides, known as couriers, who would accompany them and provide knowledge and assistance throughout the trip.

During the 19th century, the popularity of the Grand Tour increased as advancements in transportation, such as the development of railways and steamships, made travel more accessible and convenient. This allowed larger numbers of people to undertake the journey and expanded the range of destinations that could be visited.

The Grand Tour had a profound impact on European society as it exposed travelers to diverse cultures and ideas, leading to the exchange of knowledge and the spread of Enlightenment ideals. It also led to the establishment of networks and connections that played a significant role in politics, diplomacy, and the arts.

However, by the end of the 19th century , the Grand Tour began to decline in popularity. The emergence of mass tourism and the accessibility of international travel meant that the exclusivity and educational purpose of the Grand Tour were diminished. Additionally, the rise of nationalism and the changing political landscape in Europe made the idea of a unified European education less appealing.

The Grand Tour was an educational journey undertaken by the upper class during the 18th and 19th centuries. It provided young men with an opportunity to gain cultural experiences, refine their education, and establish connections across Europe. While it played a significant role in shaping European society and culture, its popularity declined as travel became more accessible and the political landscape changed.

What was the influence of the Grand Tour?

The Grand Tour had a significant influence during the 19th century. It was a traditional trip taken by young upper-class Europeans, particularly British aristocrats, to travel and experience the cultural and historical sites of Europe. This educational journey typically lasted several months to a year and was considered an essential part of a young person’s education.

The influence of the Grand Tour can be seen in various aspects:

1. Cultural Enrichment: The Grand Tour allowed travelers to visit major European cities such as Paris, Rome, Florence, and Athens, where they could study art, architecture, history, and classical literature. They would often commission renowned artists to create portraits, acquire valuable art collections, and purchase souvenirs as symbols of their cultural refinement.

2. Social Networking: The Grand Tour provided opportunities for young aristocrats to engage with fellow travelers, diplomats, and influential figures across Europe. This social networking helped establish connections, negotiate alliances, and gain a deeper understanding of European politics and society.

3. Architectural and Artistic Influence: Many wealthy travelers were inspired by the magnificent architecture, sculptures, and artworks they encountered during their journey. They brought back various architectural styles and artistic influences to their home countries, contributing to the development of neoclassical and romantic movements in art and architecture.

4. Educational Reform: The knowledge and experiences gained during the Grand Tour influenced educational reforms in the 19th century. It highlighted the importance of a broad and liberal education that encompassed not only academic subjects but also exposure to different cultures and societies.

5. Tourism Industry: The popularity of the Grand Tour led to the growth of the tourism industry in Europe. Travel agencies, guidebooks, hotels, and transportation services emerged to cater to the needs of affluent travelers, ultimately contributing to the development of modern tourism.

The Grand Tour had a profound impact on 19th-century Europe. It played a crucial role in shaping the cultural, social, architectural, artistic, and educational landscape of the time. The experiences and influences gained during the Grand Tour continue to resonate in various aspects of European society and heritage today.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the purpose and significance of the grand tour in the 19th century.

The grand tour in the 19th century was a cultural and educational journey undertaken by young European aristocrats and wealthy individuals. It had several purposes and held great significance during this time period.

1. Educational and Cultural Enlightenment: The grand tour was seen as an essential part of a young person’s education, particularly for gentlemen. It provided an opportunity to gain first-hand experience and knowledge about art, architecture, literature, and classical culture. By visiting prominent cities such as Rome, Florence, and Paris, travelers were exposed to the masterpieces of history and engaged with renowned artists and intellectuals.

2. Social Networking: The grand tour served as a way for young aristocrats to establish social connections and expand their networks. They would attend social gatherings, parties, and events hosted by influential individuals they met during their travels. These connections were valuable for political, business, and marriage prospects.

3. Symbol of Wealth and Status: Undertaking a grand tour required considerable financial resources, making it a display of wealth and social standing. Only the privileged few who could afford the expenses associated with travel, accommodation, and lavish expenditures during the journey could embark on such a tour. It became a status symbol for the upper class.

4. Collection of Art and Antiquities: One of the aims of the grand tour was to acquire valuable art, antiquities, and souvenirs to showcase one’s taste and refinement. Travelers would visit famous art galleries, archaeological sites, and markets to purchase artworks, sculptures, and other artifacts to bring back home.

5. Personal Growth and Independence: The grand tour offered a unique opportunity for young individuals to mature, gain independence, and develop their personal character. They were exposed to new cultures, languages, and customs, which broadened their perspectives and shaped their understanding of the world.

Overall, the grand tour played a significant role in shaping the cultural, social, and intellectual development of the 19th-century elite. It provided them with invaluable experiences, knowledge, and connections that played a crucial role in their personal and professional lives.

How did the grand tour shape the cultural, artistic, and intellectual development of individuals in the 19th century?

The grand tour had a significant impact on the cultural, artistic, and intellectual development of individuals in the 19th century. This traditional journey through Europe, particularly popular among the upper class, provided participants with a firsthand experience of different cultures, art, and historical landmarks.

One of the most substantial effects of the grand tour was the exposure to diverse cultural traditions and practices. Travelers would visit multiple countries, immersing themselves in the languages, customs, and traditions of each place. This exposure broadened their horizons and fostered a more cosmopolitan worldview.

In terms of artistic development, the grand tour offered aspiring artists the opportunity to view and study masterpieces of various European art movements. They would visit renowned galleries, museums, and patronize local artists. This exposure to different styles and techniques influenced their own artistic growth and allowed them to incorporate different elements into their work.

Intellectually, the grand tour provided access to some of the most esteemed educational institutions in Europe. Many participants would attend lectures and engage in intellectual conversations with scholars, philosophers, and other influential figures they encountered during their journey. This intellectual exchange allowed for the sharing of ideas, leading to the development of new perspectives and thoughts. Additionally, the travelers’ encounters with different societies and cultures challenged their preconceived notions, forcing them to critically analyze and question their own beliefs.

Furthermore, the grand tour also had a societal impact. It served as a rite of passage for young men from aristocratic families and was seen as an essential part of their education. Those who had undertaken the grand tour were often admired and respected within their own social circles, as their experiences gave them a sense of sophistication and cultural refinement.

Overall, the grand tour played a crucial role in shaping the cultural, artistic, and intellectual development of individuals in the 19th century. It opened doors to new perspectives, influenced artistic styles, and fostered intellectual growth. The impact of this traditional European journey can still be seen today in the cultural traditions and artistic influences that emerged during this period.

What were some common destinations and routes taken during the grand tour in the 19th century?

During the 19th century, the Grand Tour was a popular journey undertaken by wealthy individuals from Britain and other European countries to broaden their cultural knowledge and experiences. The common destinations of the Grand Tour varied, but some of the most popular stops included:

1. Italy: Italy was considered the highlight of the Grand Tour. Travelers would visit cities like Rome, Florence, Venice, and Naples to explore ancient ruins such as the Colosseum, the Pantheon, and Pompeii. They would also appreciate the Renaissance art and architecture found in famous galleries and churches like the Vatican Museums and the Uffizi Gallery.

2. France: France was another significant destination on the Grand Tour. Paris, with its opulent palaces, museums, and theaters, attracted many travelers. The Palace of Versailles, the Louvre Museum, and the Paris Opera were among the must-visit sites.

3. Greece: Greece held great fascination due to its ties with ancient civilization. Athens was a crucial stop to admire iconic landmarks such as the Parthenon and the Temple of Olympian Zeus.

4. Egypt: The allure of Egyptian antiquities, particularly the pyramids and temples along the Nile, made Egypt an essential part of the Grand Tour itinerary. Travelers would often embark on Nile cruises to explore attractions like the Valley of the Kings and the Luxor Temple.

5. Switzerland: The picturesque landscapes of Switzerland, including the Swiss Alps, lakes, and charming towns like Lucerne and Interlaken, provided a refreshing contrast to the more historically focused destinations.

As for the routes , there wasn’t a fixed path for the Grand Tour, as it could last several months or even years. However, a typical route might involve sailing from Britain to mainland Europe, then proceeding southwards through France towards Italy. From there, travelers might cross the Mediterranean Sea to Greece and then head eastwards to Egypt before returning to Europe via Switzerland or other countries.

Overall, the Grand Tour allowed travelers to experience different cultures, immerse themselves in art and history, and further their education in a time when international travel was an arduous undertaking.

The grand tour in the 19th century was an extraordinary journey that allowed young Europeans to broaden their horizons and immerse themselves in the rich cultural heritage of the continent. With rivalries between nations, political unrest , and the allure of new discoveries, this period witnessed a surge in travel and exploration.

The grand tour offered an unparalleled opportunity for young individuals to experience art, architecture, and history firsthand, thereby acquiring a refined education that would elevate their social status. They were exposed to the masterpieces of renowned artists such as Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael, as well as the architectural wonders of Rome, Florence, and Venice.

Moreover, the grand tour provided a platform for the exchange of ideas and knowledge across borders. Young travelers were able to meet with intellectuals, philosophers, and scholars, engaging in thoughtful conversations that influenced their perspectives and shaped their understanding of the world. This cultural exchange fostered a sense of unity among European nations and contributed to the development of a shared European identity.

However, it is important to acknowledge that the grand tour was only accessible to a privileged few. It was primarily reserved for the wealthy elite who could afford the expenses associated with such an extensive journey. This exclusivity perpetuated social hierarchies and limited access to knowledge and cultural experiences.

Overall, the grand tour was a remarkable phenomenon of the 19th century, transforming young Europeans into cultured individuals who appreciated the beauty and history of their continent. While it had its limitations, this tradition left a lasting impact on art, literature, and social norms, shaping the cultural landscape of Europe for generations to come.

To learn more about this topic, we recommend some related articles:

Bringing History to Life: Colorizing 19th Century Photos

Exploring the Masterpieces: Canadian Painters of the 19th Century

Exploring the Haunting World of 19th Century Horror Novels

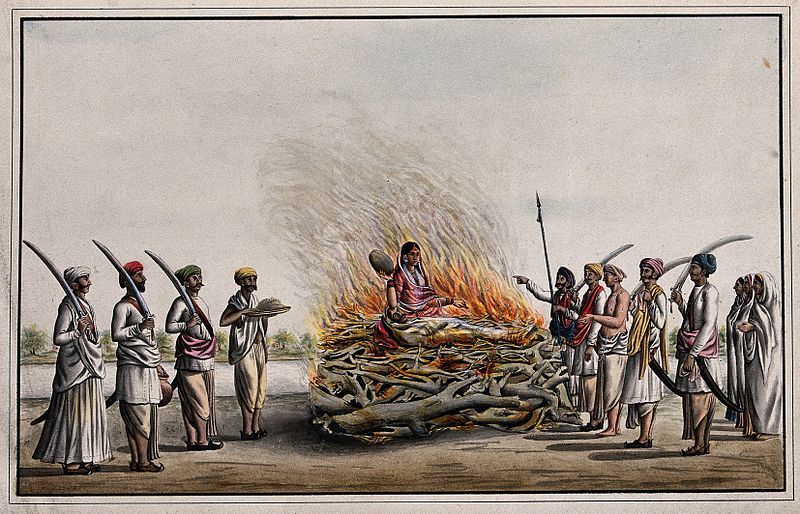

Untangling the Cultural Web: The Treatment of Widows in 19th Century India

The Legacy of French Illustrators in the 19th Century: A Visual Journey

The Role of Black Servants in 19th Century England: A Historical Perspective

The Grand Tour- the most important time in the history of tourism?

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

The Grand Tour isn’t only a TV show about cars, in actual fact, The Grand Tour is a very important part of the history of travel and tourism (and I expect this was the rationale for the name of the show ‘The Grand Tour too!). In this article I am going to teach you what The Grand Tour was, why it was so important to tourism and where the popular Grand Tour destinations were. Ready to learn more? Read on…

What is the Grand Tour?

Why is the grand tour important to tourism, the grand tour- paris, the grand tour- france onwards, the grand tour- heading north, the grand tour in the media, further reading.

The Grand Tour was the name of a traditional trip through Europe, undertaken by Upper Class boys as they were coming of age. It was mostly the British nobility and landed gentry who went on a Grand Tour, but this did extend to other wealthy Europeans and, later, South and North Americans as well as Filipinos.

According to The National Trust , the term ‘Grand Tour’ was coined by the Catholic priest and travel writer Richard Lassels (c.1603-68), who used it in his influential guidebook The Voyage of Italy (published 1670) to describe young lords travelling abroad to learn about art, architecture and antiquity.

The Grand Tour was a form of travel from around 1550-1850. It was at its most popular during the 18th century, and was said to be the way to end a boy’s education – making them a man. Often, these adolescent boys would be accompanied by tutors who would make the scenes in front of them come to life. It was more of a hands-on education, much like how we have field trips today. The Grand Tour, however, was much more lengthy.

This rite of passage was a very important point in the timeline of the history of tourism – but why?

The Grand Tour is important to the overall history of tourism because it represented travel for educational and recreational purposes rather than, for example, trade or military reasons. It contributed greatly to the cultural, social, architectural, gastronomic, political and artistic evolution of the home country’s of these travellers – especially when, as time went on, it became accessible to not only gentry but artists, collectors, designers and more. These people would take influence from the things they saw abroad. Buildings in Britain would follow architectural styles the designer had seen in Italy , for example.

It is also so important because it was during this large timeframe that the term ‘tourist’ was first properly used. Without it, the history of tourism as we know it would look massively different. People were travelling en masse (although not in groups, per se, as this was before proper public transport existed), visiting new destinations and bringing back stories of their trips. As mentioned, The Grand Tour expanded from being purely a British upper class thing to being something taken by the working class, as well as nobility from other countries. It was highly influential.

The Grand Tour paved the way for the ongoing popularity of museums – as it was clear that people who travelled to different countries often had an interest in learning about the history and culture . It proved there was a need for lodgings for people visiting from out of town; it encouraged the growth of restaurants so visitors could try the local cuisines and so on. Essentially, it was the start of what we now know as tourism because it had such a large and visible influence.

Grand Tour destinations

There was no set itinerary for a Grand Tour. It was up to the individual, and often influenced by their interests or finances. However, most people followed the same vague outline at least. Paris and Rome were firm favourites along with much of the rest of Italy, but a typical itinerary might have looked something like this – if travelling from Britain, that is…

One would start their trip properly in Dover, on the south coast of England. This remains a popular transport hub for people travelling out of the country. From here, our Grand tourist would head by boat across the channel to Ostend in Belgium or either Calais or Le Havre in France depending on their preference. Here, the tourist and their tutor (and servants, if they had any) would decide on the next move.

Often this would be to purchase a coach to transport them from place to place. This would generally be sold on again when it was time to get back on another boat – although some travellers would dismantle theirs and take it with them on their trip.

The first major stop on anyone’s Grand Tour was Paris. The capital of France and the city of love and romance, as well as baked goods, beautiful artwork and breathtaking views, Paris was an obvious choice. Grand Tourists would often hire a French speaking guide to accompany them throughout the entirety of the trip, because it was Europe’s dominant language at the time. Paris was an ideal place to acquire some to join you on a Grand Tour!

Pairs held a world of opportunities, too. Fencing tutorials, dance lessons, French language tutorships, riding practice and so much more. On top of this was the sophistication of the French high society, which would help to polish the traveller’s manners for his eventual return to England.

After getting to know Paris, one would make the journey across to Switzerland to visit either Lusanne or Geneva. This would be only a short stop, however, in order to prepare for an often-difficult journey across the Alps. The really wealthy Grand Tourists would be carried across by their servants, but generally everyone struggled together.

Awaiting them on the other side of the Alps, of course, was Italy. This is typically where our Grand Tourists would spend the most time, visiting different cities and generally exploring over the course of quite a few months. Turin and Milan would be early stops, followed by an extensive stay in Florence. Home to a larger Anglo-Italian diasporic community, Florence was an excellent part of a Grand Tour and one which allowed for a lot of fun and socialising. From here there would be shorter trips to Pisa, Padua, Bologna and Venice – the latter being a high point for many.

But this didn’t conclude the Italian part of a Grand Tour at all. Venice gave way to Rome – particularly for the study of the ancient ruins here as well as the artwork of the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque time periods. From Rome some of the more curious travellers went to Naples, where there was a big music scene, and even (after the mid 18-th century, of course) to Pompeii and Herculaneum to see the recent discoveries. Later still, some of the most adventurous Grand Tourists headed to Siciliy to see even more archaeological sites, Greece for the sunshine and culture, and Malta for its history. For the most part, however, Naples or Rome were the usual end to an Italian adventure.