1999 Tour de France results

86th edition: july 3 - july 25, 1999, results, stages with running gc, map, photos and history.

1998 Tour | 2000 Tour | Tour de France database | Quick Facts | Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1999 Tour de France

1999 Tour de France map

Les Woodland's book Dirty Feet: How the great unwashed created the Tour is France is available as an audiobook here . For the print or Kindle eBook versions, just cick on the Amazon link on the right.

1999 Tour de France Quick Facts:

3,686.8 km, traveled at a then record average speed of 40.276 km/hr.

180 starters and 141 classified finishers

Erik Zabel wins his 4th Green Jersey for best sprinter.

Richard Virenque wins his 5th Polka Dot Jersey for best climber.

For various reason, the winners of the previous three Tours (Ullrich, Pantani and Riis) did not participate.

The Tour was effectively won by Armstrong in the second stage when there was a mass crash, destroying the hopes of his competitors, notably Alex Zülle.

This did not become apparent until the stage nine finish at Setrieres, where Armstrong's lead was a solid 6min 3sec

In 2012 Lance Armstrong was stripped of all of his Tour wins after his doping became known.

- Lance Armstrong (US Postal) 91hr 32min 16sec

- Alex Zülle (Banesto) @ 7min 37sec

- Fernando Escartin (Kelme) @ 10min 26sec

- Laurent Dufaux (Saeco) @ 14min 43sec

- Angel Luis Casero (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 15min 11sec

- Abraham Olano (ONCE) @ 16min 47sec

- Daniele Nardello (Mapei) @ 17min 2sec

- Richard Virenque (Polti) @ 17min 28sec

- Wladimir Belli (Festina) @ 17min 37sec

- Andrea Peron (ONCE) @ 23min 10sec

- Kurt Van De Wouwer (Lotto) @ 23min 32sec

- David Etxebarria (ONCE) @ 26min 41sec

- Tyler Hamilton (US Postal) @ 26min 53sec

- Stéphane Heulot (FDJ) @ 27min 58sec

- Roland Meier (Cofidis) @ 28min 44sec

- Benoît Salmon @ 28min 59sec

- Alberto Elli (Telekom) @ 33min 39sec

- Paolo Lanfranchi (Mapei) @ 34min 14sec

- Carlos Contreras (Kelme) @ 34min 53sec

- Georg Totschnig (Telekom) @ 37min 10sec

- Mario Aerts (Lotto) @ 39min 21sec

- Giuseppe Guerini (Telekom) @ 39min 29sec

- Gianni Faresin (Mapei) @ 40min 28sec

- Álvaro González de Galdeano (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 43min 39sec

- Marcos Antonio Serrano (ONCE) @ 45mn 3sec

- Francisco Tomas García (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 45min 31sec

- Christophe Moreau (Festina) @ 45min 34sec

- Francisco Mancebo (Banesto) @ 50min 31sec

- Luis Perez (ONCE) @ 52min 53sec

- François Simon (Credit Agricole) @ 53min 21sec

- Armin Meier (Saeco) @ 1hr 0min 10sec

- Stefano Garzelli (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 0min 45sec

- Javier Pascual (Kelme) @ 1hr 1min 20sec

- Massimiliano Lelli (Cofidis) @ 1hr 1min 27sec

- Alexandre Vinokourov (Casino) @ 1hr 2min 23sec

- Kevin Livingston (US Postal) @ 1hr 6min 10sec

- José Joaquim Castelblanco (Kelme) @ 1hr 8min 5sec

- Salvatore Commesso (Saeco) @ 1hr 9min 15sec

- César Solaun (Banesto) @ 1hr 10min 1sec

- Udo Bölts (Telekom) @ 1hr 11min 51sec

- Steve De Wolf (Cofidis) @ 1hr 11min 54sec

- Frédéric Bessy (Casino) @ 1hr 15min 26sec

- Miguel Angel Peña (Banesto) @ 1hr 19min 26sec

- Laurent Madouas (Festina) @ 1hr 20min 42sec

- Geert Verheyen (Lotto) @ 1hr 23min 24sec

- José Luis Arrieta (Banesto) @ 1hr 24min 29sec

- Francisco Javier Cerezo (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 1hr 26min 50sec

- Thierry Bourguignon (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 1hr 27min 43sec

- Manuel Fernández (Mapei) @ 1hr 30min 20sec

- Mariano Piccoli (Lampre) @ 1hr 31min 21sec

- Lylian Lebreton (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 1hr 32min 51sec

- Jean-Cyril Robin (FDJ) @ 1hr 33min 14sec

- Marco Fincato (Merctone Uno) @ 1hr 36min 57sec

- Jon Odriozola (Banesto) @ 1hr 41min 55sec

- Marco Serpellini (Lampre) @ 1hr 42min 4sec

- Michael Boogerd (Rabobank) @ 1hr 42min 22sec

- Fabian Jeker (Festina) @ 1hr 42min 25sec

- Rafael Diaz (ONCE) @ 1hr 43min 36sec

- José Javier Gomez (Kelme) @ 1hr 45min 50sec

- Jens Voigt (Credit Agricole) @ 1hr 47min 47sec

- Santos González (ONCE) @ 1hr 48min 21sec

- Dimitri Konyschev (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 49min 10sec

- Peter Farazijn (Cofidis) @ 1hr 55min 1sec

- Hernán Buenahora (Vatalicio Seguros) @ 1hr 55min 33sec

- Frankie Andreu (US Postal) @ 1hr 59min 1sec

- Stefano Cattai (Polti) @ 1hr 59min 49sec

- Christophe Oriol (Casino) @ 2hr 1min 6sec

- José Vicente Garcia (Banesto) @ 2hr 1min 46sec

- Fabrice Gougot (Casino) @ 2hr 2min 5sec

- Christophe Mengin (FDJ) @ 2hr 4min 3sec

- Rik Verbrugghe (Lotto) @ 2hr 4min 31sec

- Marc Lotz (Rabobank) @ 2hr 8min 8sec

- Steffen Wesemann (Telekom) @ 2hr 9min 22sec

- Stéphane Goubert (Polti) @ 2hr 10min 58sec

- José Luis Rebollo (ONCE) @ 2hr 12min 57sec

- Prudencio Indurain (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 2hr 14min 15sec

- Laurent Brochard (Festina) @ 2hr 14min 42sec

- George Hincapie (US Postal) @ 2hr 16min 35sec

- Chirstophe Rinero (Cofidis) @ 2hr 16min 35sec

- Jörg Jaksche (Telekom) @ 2hr 16min 44sec

- Giampaolo Mondini (Cantina Tollo) @ 2hr 17min 34sec

- Gilles Maignan (Casino) @ 2hr 18min 2sec

- Cédriv Vasseur (Credit Agricole) @ 2hr 18min 23sec

- Maarten Den Bakker (Rabobank) @ 2hr 19min 3sec

- Christian Vande Velde (US Postal) @ 2hr 23min 58sec

- Javier Otxoa (Kelme) @ 2hr 24min 14sec

- Riccardo Forconi (Mercatone Uno) @ 2hr 25min 2sec

- Laurent Lefèvre (Festina) @ 2hr 25min 8sec

- Erik Zabel (Telekom) @ 2hr 26min 1sec

- Dominique Rault (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 27min 17sec

- Pascal Chanteur (Casino) @ 2hr 28min 0sec

- Elio Aggiano (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 2hr 28min 33sec

- Alexei Sivakov (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 29min 40sec

- Stuart O'Grady (Credit Agricole) @ 2hr 30min 7sec

- Massimo Giunti (Cantina Tollo) @ 2hr 30min 25sec

- Thierry Gouvenou (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 32min 11sec

- Patrick Jonker (Rabobank) @ 2hr 32min 20sec

- David Navas (Banesto) @ 2hr 33min 31sec

- Fabio Sacchi (Polti) @ 2hr 33min 39sec

- Laurent Desbiens (Cofidis) @ 2hr 34min 1sec

- José Angel Vidal (Kelme) @ 2hr 34min 22sec

- Jaime Hernández (Festina) @ 2hr 36min 4sec

- Davide Bramati (Mapei) @ 2hr 36min 15sec

- Tom Steels (Mapei) @ 2hr 36min 28sec

- Anthony Morin (FDJ) @ 2hr 36min 37sec

- Frédéric Guesdon (FDJ) @ 2hr 37min 27sec

- Erik Dekker (Rabobank) @ 2hr 38min 5sec

- Fabien De Waele (Lotto) @ 2hr 39min 21sec

- Beat Zberg (Rabobank) @ 2hr 39min 29sec

- Kai Hundertmarck (Telekom) @ 2hr 39min 32sec

- Ludovic Auger (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 39min 38sec

- Peter Wuyts (Lotto) @ 2hr 39min 50sec

- Marco Pinotti (Lampre) @ 2hr 40min 0sec

- Silvio Martinello (Polti) @ 2hr 40min 14sec

- Christophe Capelle (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 45min 17sec

- Lars Michaelsen (FDJ) @ 2hr 46min 20sec

- Claude Lemour (Cofidis) @ 2hr 46min 26sec

- Rolf Huser (Festina) @ 2hr 47min 27sec

- Chris Boardman (Credit Agricole) @ 2hr 47min 48sec

- Mirko Crepaldi (Polti) @ 2hr 49min 14sec

- Henk Vogels (Credit Agricole) @ 2hr 49min 17sec

- Robbie McEwen (Rabobank) @ 2hr 49min 23sec

- Sébastien Hinault (Credit Agricole) @ 2hr 51min 3sec

- Sergio Barbero (Mercatone Uno) @ 2hr 51min 9sec

- Gabriele Colombo (Cantina Tollo) @ 2hr 51min 43sec

- Carlos de la Cruz (Big Mat-Auber 93) @ 2hr 51min 48sec

- Rossano Brasi (Polti) @ 2hr 52min 1sec

- Thierry Marichal (Lotto) @ 2hr 54min 6sec

- Juan José de Los Angeles (Kelme) @ 2hr 54min 40sec

- Sebastien Demarbaix (lotto) @ 2hr 58min 32sec

- Marcus Lungqvist (Catina Tollo) @ 3hr 0min 9sec

- Anthony Langella (Credit Agricole) @ 3hr 2min 20sec

- Bart Leysen (Mapei) @ 3hr 3min 11sec

- Massimiliano Napolitano (Mercatone Uno) @ 3hr 5min 9sec

- Pedro Horillo (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 3hr 5min 31sec

- Jan Schaffrath (Telekom) @ 3hr 5min 41sec

- Luca Mazzanti (Cantina Tollo) @ 3hr 6min 28sec

- Alessandro Baronti (Cantina Tollo) @ 3hr 7min 7sec

- Thierry Loder (Cofidis) @ 3hr 11min 55sec

- Pascal Deramé (US Postal) @ 3hr 14min 19sec

- Jacky Durand (lotto) @ 3hr 19min 9sec

- Richard Virenque (Polti): 279 points

- Alberto Elli (Telekom): 226

- Mariano Piccoli (Lampre): 205

- Fernando Escartin (Kelme): 194

- Lance Armstrong (US Postal): 193

- Alex Zülle (Banesto): 152

- José Luis Arrieta (Banesto): 141

- Laurent Dufaux (Saeco): 141

- Andrea Peron (ONCE): 138

- Kurt Van De Wouwer (Lotto): 117

- Erik Zabel (Telekom): 323 points

- Stuart O'Grady (Credit Agricole): 275

- Christophe Capelle (Big Mat-Auber 93): 196

- Tom Steels (Mapei): 188

- François Simon (Credit Agricole): 186

- George Hincapie (US Postal): 166

- Robbie McEwen (Rabobank): 166

- Giampaolo Mondini (Cantina Tollo): 141

- Christophe Moreau (Festina): 140

- Silvio Martinello (Polti): 130

- Benoît Salmon (Casino) 92hr 1min 15sec

- Mario Aerts (Lotto) @ 10min 22sec

- Francisco Tomas García (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 16min32sec

- Francisco Mancebo (Banesto) @ 21min 32sec

- Luis Perez (ONCE) @ 23min 54sec

- Banesto: 275hr 5min 21sec

- ONCE @ 8min 16sec

- Festina @ 16min 13sec

- Kelme @ 23min 48sec

- Mapei @ 24min 13sec

- Telekom @ 41min 0sec

- Vitalicio Seguros @ 42min 44sec

- US Postal @ 57min 13sec

- Cofidis @ 58min 2sec

- Lotto @ 1hr 9min 2sec

Content continues below the ads

Stage results with running GC:

Prologue , Saturday, July 3, Puy de Fou 6.8 km Individual Time Trial

Stage 1 : Sunday, July 4, Montaigu - Challans. 209 km. 42.12 km/hr

General Classification after Stage 1:

Stage 2: Monday, July 5, Challans - St. Nazaire. 146 km. 46.822 km/hr

General Classification after Stage 2

Stage 3 : Tuesday, July 6, Nantes - Laval 194 km. 43.31 km/hr

General Classification after Stage 3

Stage 4 , Wednesday, July 7, Laval - Blois, 194.5 km. 50.355 km/hr

Fastest stage to date in Tour history

General Classification after Stage 4

Stage 5 : Thursday, July 8, Thursday, Bonneval - Amiens. 228 km

General Classification after Stage 5

Stage 6 : Friday, July 9, Amiens - Maubeuge, 169 km

General Classification after Stage 6

Stage 7 : Saturday, July 10, Avesnes sur Helpe - Thionville, 223 km

General Classification after Stage 7

Stage 8 : Sunday, July 11, Metz 56.5 km Individual Time Trial 49.417 km/hr

Bobby Julich crashes at about km 30 and is forced to retire

General Classification after Stage 8

Stage 9 : Tuesday, July 13, Le Grand Bornand - Sestrieres, 213.5 km.

General Classification after Stage 9

Stage 10 : Wednesday, July 14, Sestrieres - L'Alpe d'Huez. 220.5 km 32.868 km/hr

General Classification after Stage 10

Stage 11 : Thursday, July 15, Bourg d'Oisans - St. Etienne. 198.5 km

General Classification after Stage 11

Stage 12 : Friday, July 16, St. Galmier - St. Flour, 201.5 km

General Classification after Stage 12

Stage 13 : Saturday, July 17, St. Flour - Albi. 236.5 Km. 1999's longest stage.

General Classification after Stage 13

Stage 14 : Sunday, July 18, Castres - St. Gaudens, 199 km

GC after Stage 14:

- Lance Armstrong: 67hr 23min 28sec

- Abraham Olano @ 7min 44sec

- Alex Zulle @ 7min 47sec

- Laurent Dufaux @ 8min 7sec

- Fernando Escartin @ 8min 53sec

- Stephane Heulot @ 9min 10sec

- Richard Virenque @ 10min 3sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 10min 18sec

- Daniele Nardello @ 10min 58sec

- Angel Casero @ 11min 13sec

Stage 15 : Tuesday, July 20, St. Gaudens - Piau Engaly, 173 km.

General Classification after Stage 15. 40.007 km/hr average speed for the Tour so far

Stage 16 : Wednesday, July 21, Lannemezan - Pau 192 km

General Classification after Stage 16.

Stage 17 : Thursday, July 22, Mourenx - Bordeaux 199 km.

General Classification after Stage 17. 3,301.8 km ridden so far @ 40.058 km/hr average speed

Stage 18 : Friday, July 23. Jonzac - Futuroscope. Shortened to 184.7 km.

GC after Stage 18:

- Lance Armstrong: 86hr 46min 20sec

- Fernando Escartin @ 6min 15sec

- Alex Zulle @ 7min 28sec

- Laurent Dufaux @ 10min 30sec

- Richard Virenque @ 11min 40sec

- Daniele Nardello @ 13min 19sec

- Angel Casero @ 13min 34sec

- Abraham Olano @ 14min 29sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 15min 14sec

- Kurt Van de Wouwer @ 18min 27sec

Stage19 : Saturday, July 24, Futuroscope 57 km individual time trial. Armstrong averaged 50.085 km/hr

General Classification after Stage 19

Stage 20 : Sunday, July 25, Arpajon - Paris/Champs Elysées, 143.5 km

Complete Final General Classification after Stage 20.

The Story of the 1999 Tour de France:

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Tour de France", Volume 2. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, Kindle eBook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will the purchase easy.

Over the winter more allegations of drug use surfaced. Some could not be confirmed, others were obvious on their face. The conclusion one had to come to after digesting the accumulation of horrible information is that the situation was at least as bad or worse than the 1998 Tour led one to believe. And then the situation managed to deteriorate. After stage 5 in the 1999 Giro, the Italian National Sports Council (CONI) subjected 16 riders from 3 different teams to a new comprehensive blood and urine test. Two of the riders tested positive for dope but no sanctions were applied. The riders, as they have always been since the start of testing, were incensed. Marco Pantani, Oscar Camenzind, Laurent Jalabert and Mario Cipollini held a press conference and declared that if the national sports organization intruded any further upon the testing regimen which had heretofore been the responsibility of the UCI, they would stop racing. Of that group of 4, Pantani was not the only rider who would have drug problems. In 2004 Camenzind retired after receiving a 2-year suspension for EPO.

Before the start of the penultimate stage of the 1999 Giro, Marco Pantani was awakened so that a blood test could be administered. His hematocrit of 52 percent resulted in his being ejected from the Giro after he had won 4 stages and was leading in the General Classification. The cycling world was stunned. Pantani's squalificato seemed to affect many racing fans far more deeply than the Festina scandal, probably because of Pantani's powerfully heroic image. He had triumphed over a horrible accident and saved the Tour during its greatest crises. Partisans of Pantani made accusations of a conspiracy. In fact, the riders have long known how to foil the hematocrit test. When they knew they would be subjected to a test they would take saline injections and aspirin and in no time the rider's hematocrit was within the legal limit. Some teams even provided the riders with small centrifuges so that they could "manage" their red blood cell concentration. By waking Pantani up to take the test he wasn't able to take measures to bring his hematocrit down. He was a goner. Pantani was too devastated by the disqualification to consider riding the Tour.

In mid-June the Tour announced that the TVM team along with several individuals including ONCE team manager Manolo Saiz and rider Richard Virenque would not be allowed to participate in the Tour. Missing from the list of banned riders were the Festina and Mercatone Uno teams and Marco Pantani. Later on the UCI overruled the Tour organization and insisted that the Tour allow Virenque and Saiz to participate. And the doping in pro racing continued with 4 riders tossed from the Tour of Switzerland for high hematocrits.

In June Ullrich announced that he had injured his knee in the Tour of Germany and would not be able to compete in the Tour. With Pantani and Ullrich out, the press cast about for a favorite. At the top of a lot of lists were Pavel Tonkov (1996 Giro winner), Alex Zülle, Fernando Escartin and Ivan Gotti (1997 and 1999 Giro winner).

And there was another rider to consider. He had withdrawn from the 1996 Tour and could not ride the 1997 and 1998 editions as he endured surgery and chemotherapy to cure what should have been a life-ending case of testicular cancer. In the fall of 1997 he announced the resumption of his professional cycling career. That return was bumpy with intermittent success and withdrawals. But by mid 1998 he had clearly returned to the top ranks of professional cycling with a win in the Tour of Luxembourg, fourth in the Vuelta and fourth in the World Time Trial Championships. In 1999 he won the prologue of the Dauphiné Libéré, and narrowly lost a 2-up sprint to Michael Boogerd in the Amstel Gold Race. Lance Armstrong had returned. But he returned a different athlete. The man who had been a strong, punchy 175-pound powerhouse and who was one of the youngest-ever World Road Champions was now a gaunt, lean stage racer. He now trained and raced with a deliberate focus that turned out to be his most powerful weapon against his usual challenger, Jan Ullrich.

When Armstrong was diagnosed with cancer, he had just inked a $2.5-million, 2-year contract with the French team Cofidis. When Armstrong told Cofidis he was ready to return to racing they responded by firing him. Now Cofidis boss François Migraine didn't quite see it that way. He said that he was told Armstrong had testicular cancer two weeks after the Cofidis contract was signed. He said he promised to support Armstrong even if he couldn't fulfill the contract. Saying that he did not hear much from Armstrong, he sent Alain Bondue to the U.S. to find out what was happening exactly and to renegotiate the contract.

It is Bondue's renegotiating of the contract while Armstrong was so sick that infuriated the rider.

Migraine says that Cofidis did end up paying Armstrong approximately $600,000 to settle the contract and had reached a tentative agreement for the 1998 season before Armstrong signed for US Postal.

After a hard search for a new team Armstrong signed with the American US Postal squad and it was in their blue outfit that he was riding the Tour. While Armstrong was not on many possible Tour winner lists, Miguel Indurain had said that he thought Armstrong had a serious chance of winning the Tour.

With Pantani, Ullrich and Riis not starting the Tour, 1999 was one of those rare years in which there were no former Tour winners. The 1999 Tour started in the Loire Valley town of Le-Puy-de-Fou and went clockwise (Alps first) up to northeastern France and then a big transfer to begin the Alps on stage 9. After the Alps came the Massif Central, the Pyrenees and then the final time trial on the penultimate stage.

Armstrong showed that he had mastered the first component of a successful Tour rider, time trialing, winning the 6.8-kilometer prologue and beating Zülle by 7 seconds. Armstrong said that this day was doubly sweet, that he got more than the pleasure of the Yellow Jersey. After completing his ride and learning that he was the winner, he went by the Cofidis team who were there with the team managers. These were the managers who had come to his hospital bed when he was in the worst throes of chemotherapy and told him that they needed to re-do his contract. "That was for you," he told them.

The Tour was upended on the second stage. Starting at Challans, southeast of Nantes, the riders were sent to the island of Noirmoutier before returning to the mainland and a finish in St. Nazaire. The riders had to negotiate the Passage du Gois, a narrow 4-kilometer long road that is submerged except at low tide. Even when exposed, it is a dangerous, slippery road. Worse, there was a hard crosswind. Making the situation even more dire, the entire peloton reached the constricted road intact. Armstrong, Olano, Escartin, Tonkov, Virenque and Julich were in the front of the pack when it made the treacherous crossing and emerged unscathed. But behind them was chaos. A crash took down Zülle, Gotti and Michael Boogerd who were then badly delayed in the mess. The teams that had managed to get clear of the passage without damage went to the front of the lead group and pulled hard in order to derive the maximum benefit. The Zülle group eventually came in 6 minutes, 3 seconds after Tom Steels led in the front lucky 70 riders. At one terrible, early blow, Zülle, a wonderfully talented but accident-prone rider, was out of contention. With the time bonuses the sprinters were earning, Estonian sprinter Jaan Kirsipuu was now the leader with Armstrong only 14 seconds back in second place.

Stage 4 was notable because tailwinds allowed the riders to set a new record for the fastest road stage, 50.356 kilometers per hour, beating the 1993 record held by Johan Bruyneel.

While there were several fine sprinters in the 1999 Tour, the finest, far and away, was Tuscan Mario Cipollini. By the end of stage 7 he had done what no postwar rider had done, win 4 stages in a row. One had to go back to the 1930 Tour when Charles Pélissier was the reigning speed demon to find the last 4-time consecutive stage winner. As they raced over the flatter roads of Northern France, the fast finishers enjoyed the time in the Tour when they could strut their stuff. The next day, in Metz, was a 56.5-kilometer individual time trial. Then the mountains had to be conquered. The General Classification men would come out of hiding after a period where their primary job had been to avoid trouble.

During the time trial, misfortune struck 2 important riders. Bobby Julich crashed and had to abandon. Abraham Olano crashed and lost enough time that the man who started after him, Armstrong, caught and passed him. Armstrong's victory in the stage was substantial. Zülle, who came in second, could only come within 57 seconds of him. The new General Classification with a rest day to be followed by the first Alpine stage:

The remaining big question was whether Armstrong could climb with men like Zülle, Escartin and Virenque. Before he came down with cancer, he couldn't. The ninth stage would certainly settle the question with the Tamié, Télégraphe, Galibier, Montgenèvre and a hilltop finish at Sestriere on the day's menu. It was a cold, wet day with hail on the descent of the Montgenèvre. Virenque got away on the Galibier and was the first over the Montgenèvre but couldn't hold his lead. On the descent of the Montgenèvre Escartin and Gotti took wild chances and managed to create a gap of about 30 seconds. On the final climb a small group of 5 of the best including Armstrong and Zülle were together. With less than 7 kilometers to go Armstrong jumped away. He caught and passed Escartin and then went right on by a dumbfounded Gotti. With the encouragement of Bruyneel coming over his earphone Armstrong rode ever harder and further from his chasers. The only credible threat coming up the road was from Zülle, but he couldn't do it. Armstrong crossed the line alone, 31 seconds ahead of Zülle and 2½ minutes ahead of Virenque.

The new General Classification:

Armstrong was now in the ideal position. He had a healthy lead, one so large that he could ride economically, just keeping his dangermen in check. He didn't have to waste energy on offensive exploits. In fact, he had been in control since the crash in stage 2 but insecurity about Olano's climbing abilities had prevented US Postal from relaxing. Armstrong adopted exactly that conservative strategy for the next day's stage to the top of L'Alpe d'Huez. With over 6 minutes in hand he planned to avoid disaster and let the others try to take the race from him. At the base of the Alpe the fast pace caused Olano to drop off. Part way up the climb Italian Giuseppe Guerini took flight with Tonkov hot on his tail. Tonkov couldn't close the gap but he was just dangerous enough that Armstrong went after him. Near the top a photographer got right in Guerini's way and the 2 went down together. Guerini jumped back on his bike and was able to regain his momentum and stayed away for a terrific victory with Tonkov only 21 seconds back. The Armstrong/Zülle group came within 4 seconds of Tonkov at the end. The net result for the day with Olano's 2-minute time loss was that Armstrong now had a lead of 7 minutes, 42 seconds over the still second placed Spaniard. Zülle was now third, 5 seconds behind Olano.

Now the Tour went across the Massif Central. While this terrain didn't have the dramatic climbs of the Alps and the Pyrenees, the sawtooth stage profiles were demanding. An escape could do damage if the leaders' teams weren't alert and willing to work hard. Stage 12 was a classic stage of this sort with 6 climbs rated category 2 and 3; stage 13 had 7 rated climbs. While these days were characterized by constant attacks and high temperatures, the top of the standings didn't change.

Before the start of the 2 Pyrenean stages the Tour took its second rest day. There were now 3 stages left that could affect the Tour's outcome: the 2 remaining days in the mountains and the 57-kilometer time trial. If the pure climbers wanted to take back time from Armstrong, time was running out.

Stage 15 had 6 big mountains: the Ares, Menté, Portillon, Peyresourde, Val Louron, and a hilltop finish at Piau-Engaly. From the first climb the non-stop attacks started. Virenque, Laurent Brochard and others shattered the peloton. In the now-reduced pack, US Postal kept a high but not hot pace since most of the breakaways were not threats to the leadership. But when Fernando Escartin took off on the Portillon, Armstrong himself closed the gap. Escartin went again on the Peyresourde and began to hook up with riders who had escaped earlier. Escartin dropped all the other riders and soloed in for the win. Virenque and Zülle, who had been able to withstand Armstrong's attempts to drop them, managed to beat the Yellow Jersey to the finish by 9 seconds. For Armstrong and his team those final kilometers of that stage represented a rare episode of support failure. Armstrong bonked. He ran out of food and couldn't keep up with the others. Again Olano had been the main casualty, this day coming in 7 minutes after Escartin and losing his second place in the standings.

That afternoon rumors became more solid when the French paper Le Monde announced that a drug test had shown Armstrong to be using a corticosteroid. The cycling press could not believe that Armstrong could emerge from cancer and be the extraordinary stage racer he had become, and delightedly fanned the rumors. It turned out to be the skin cream Armstrong had been using to fight saddle sores. It contained minute traces of cortisone but Armstrong had been cleared by the Tour authorities to use the medicine.

Stage 16 would be tough with the Aspin, Tourmalet, Soulor and the Aubisque. With a descent into Pau after the final climb, this stage would not give the pure climbers the chance to get real time if Armstrong should falter. While there was action off the front, Armstrong stayed focused on his rivals. On the Tourmalet, a hard acceleration by Postal rider Kevin Livingston caused Virenque to lose contact. The main worries were Escartin and Zülle who were both indefatigable and strong. At the top of the Tourmalet Escartin attacked and took Zülle and Armstrong with him. Escartin tried again on the Soulor and again Armstrong stayed with him. In the final drive to Pau Armstrong let the others go, not needing to fight for a stage win or further tire himself. After the Pyrenees the General Classification stood thus:

Armstrong chose to ride the stage 19 time trial to win, rather than playing it safe and riding carefully. But he beat Zülle by only 9 seconds. The main loser of the day was Escartin, who not unexpectedly, lost gobs of time and his second place. The Tour was now Armstrong's. Like the 1971 Tour (when Ocaña crashed out while in Yellow), this is a Tour that invites speculation. What if Zülle had not crashed in the Passage du Gois and lost 6 minutes? Now I understand that all the riders had to ride the same roads, it was the same for everyone and Armstrong was the heads-up savvy rider who made sure he was in the front of the peloton on that dangerous road. But if Zülle, who did crash a lot, had not lost that time, then perhaps Armstrong would not have had the luxury of a defensive ride. It would surely have been a closer Tour that might have gone another way.

Armstrong joined an elite group (Merckx, Hinault and Indurain) when he won all of the 1999 Tour's time trials. That French cycling was still at a low ebb was made clear. The highest placed Frenchman was Virenque at eighth place, 17 minutes, 28 seconds behind Armstrong. For the first time since 1926, in the era of Belgian Tour hegemony, no Frenchman had won a stage. In 1926 the highest placed French rider came in eighth as well.

Final 1999 Tour de France General Classification:

Climbers' Competition:

Points Competition:

© McGann Publishing

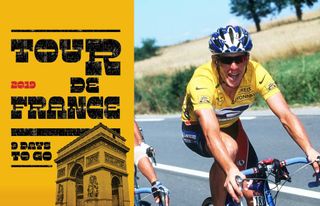

1999 Tour de France: The farce of renewal

Looking back 20 years to the post-Festina Tour and the falsest of dawns

Twenty years ago, the Tour de France was vaunted by the organisers as 'The Tour of Renewal'. It was 12 months after the Festina doping affair had almost brought the race to its knees, but hopes for a new dawn were made a mockery of as failed doping tests were covered up, clean riders were vilified, and speeds were faster than ever.

The End of the Road: The Festina Affair and the Tour that Almost Wrecked Cycling by Alasdair Fotheringham - Book Extract

Austrian doping: A complete history of Operation Aderlass

How to watch the Tour de France - free live streams from anywhere

Tour de France 2019: The Essential Guide

2020 Tour de France to start in June as Tokyo Olympics sparks a calendar squeeze

In the latest feature in Cyclingnews' annual countdown to the Tour de France, Jean-François Quénet, who covered the 1999 Tour with a sceptical view of Lance Armstrong, recalls a farcical three weeks.

It started with a dispute between ASO and the UCI. 17 days prior to the start in Le Puy-du-Fou in the Vendée province, race director Jean-Marie Leblanc and ASO president Jean-Claude Killy rejected the participation of the TVM team and a few individuals like Richard Virenque and Manolo Saiz, who were considered troublemakers and harmful to the image of the Tour de France.

However, three days before the prologue, the UCI instructed the organisers to reinstate Virenque and Saiz, who had made an appeal because the rule of a 30-day limit to enter participants hadn’t been respected by ASO. At the time, wildcards were given after the Critérium du Dauphiné and that rule was hardly respected by any organizers or teams but Leblanc declared himself “legalist” and didn’t argue. His morning run together with UCI president Hein Verbruggen was widely commented upon.

Love him or hate him - there wasn't much room for moderation - Virenque was at the centre of attention but there was no previous winner of the Tour de France on the start list; Bjarne Riis and Jan Ullrich were injured and Marco Pantani was in no mood to ride after being expelled from the Giro d'Italia for failing a haematocrit test. There was no five-star favourite but on the morning of the race, L’Équipe rated Lance Armstrong at four stars along with Abraham Olaño. The American was surely the hot favourite for the prologue, having won short time trials at Circuit de la Sarthe and the Dauphiné, it was just not sure how well he’d go in the mountains.

As Alex Zülle, riding for Banesto, crashed on the Passage du Gois – the road from the Noirmoutier island that floods with the tide – Saiz urged his ONCE team to pull as an act of revenge one year after the Swiss rider [a member of the Festina team in 1998] told the French police that doping was also a common practice at ONCE, his former team.

In their introduction of the ‘Tour of Renewal’, race organiser ASO had declared they’d be happy with the race being 3km/h slower than 1998. However, after one week, the average speed was faster than ever: 43.737km/h. Armstrong’s performance against the clock on the 56.5km course around Metz was a shock: 49.416km/h. It was superior to Miguel Indurain’s similar domination seven years before in the nearby Luxemburg (49.028km/h).

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

During the first rest day’s press conference, the Texan was already facing a barrage of questions.

“I assure you that I don’t dope,” he firmly stated in Le Grand Bornand.

Armstrong grew frustrated at the scepticism from the media

Monsieur Propre

Once through the Alps, where Armstrong also outclassed his rivals, the Tour was back to its old traditions. Just one year and one week since Festina’s soigneur Willy Voet had been arrested at the Franco-Belgian border, sparking the Festina affair, Leblanc was giving out medals to other Belgian soigneurs for reaching 20 participations in the Tour. Virenque was back in the polka dot jersey; it was business as usual.

Banners read: 'Armstrong at home, Bassons in the peloton' and 'For Bassons, against doping'

There was, however, a glitch. A former Festina rider refused to subscribe to the so-called omertà, the old-school law of silence respected through the ages by the cycling community.

During questioning by police in the heat of the previous year's scandal, Festina riders Christophe Moreau and Armin Meier had both opened up about the prevalence of doping but had both highlighted an exception to the rule. Christophe Bassons, they insisted, did not dope.

Riding the 1999 Tour de France for La Française des Jeux [now Groupama-FDJ], Bassons had a column in the daily newspaper Le Parisien. He didn’t say much, even if, the day after Armstrong’s stage win in Metz, he ironically questioned: “But what was the EPO for?” However, every day his column was introduced with: 'Useful precision: Bassons rides on clear water, which means doping free'.

That did not go down well with the rest of the peloton. At the beginning of stage 10, following his solo win in Sestrières, Armstrong tried to bully Bassons in the peloton, and realised the Frenchman could understand English. He told him he should shut up, that there was uncertainty surrounding his team’s sponsor, and he’d better think of his own interests. Bassons replied that he was rather thinking of the interest of the next generation of cyclists and that he could just as well take on another job. An increasingly irritated Armstrong advised him to quit cycling on the spot.

As Armstrong’s performances started to attract suspicion, media interest in Bassons, who went on to become known as 'Monsieur Propre' (Mr Clean) picked up. Jealousy seemingly grew not just in the peloton but inside his team, too. He was criticised by his teammate Stéphane Heulot and even his sport director Marc Madiot, the current Groupama-FDJ manager, who told him to rest instead of giving lengthy interviews.

And so Bassons suddenly left the Tour on the morning of stage 12, sending reporters scrambling across France, looking for him in various airports.

Corticoids and tear gas

General media interest in the race, however, decreased during the transition stages between the Alps and the Pyrenees, and Armstrong was trying to keep a low profile. "I’ve stopped attacking because every time I do it, the press suspects me of doping," he lamented.

There was more scandal around the corner. Stage 11 winner Ludo Dierckxsens didn’t fail the new doping test for corticoids but messed up when declaring to the doping control officer which medicines he'd taken for a supposed knee injury, accidentally naming a banned corticoid. His Lampre team were already on thin ice after television reporters had found dubious medical waste in their rubbish bins during the Tour de Suisse. And so when they themselves kicked Dierckxsens out of the Tour for self-medication, there was no escaping the suspicion that the Belgian champion was a fall-guy, sacrificed on the altar as they scrambled to scrub clean their image.

There was to be a failed doping test for corticoids, as it emerged that triamcinolone had been detected in the urine of none other than Lance Armstrong, in a sample taken after stage 1. The American, however, remained in the race. He defended himself, arguing that he’d used a skin cream to treat saddle sores, and presented the UCI with a back-dated medical prescription for the substance. The UCI, in complete breach of its anti-doping rules, signed it off and the race went on.

In the Pyrenees, the atmosphere of the race was lousy. Cofidis' Christophe Rinero, fourth overall and King of the Mountains in the 1998 Tour, got himself into an argument with spectator, who yelled at him: "It was easier with EPO!" This time, Rinero would go on to finish 79th. During stage 19 to Bordeaux, tear gas was sprayed from the crowd onto the riders, and many had to stop to wash their burning eyes.

Long live EPO reads a sarcastic banner in the Pyrenees

Armstrong won the penultimate-day time trial at Futuroscope, and did so at an even higher speed than in Metz, which was before all the mountain stages. His average speed of 50.085km/h was followed 24 hours later in Paris by a new record speed for the Tour as a whole: 40.273km/h.

Those records, of course, have not stood the test of time.

Twenty years ago, even the observers who didn’t believe that Armstrong was riding clean gave him credit for the message of hopes he delivered as a cancer survivor. Since then, the evidence of the fraud has gradually emerged and resulted in his titles being nullified.

That took more than 10 years, and the UCI took a similar amount of time to start piecing back together its credibility. Seven years after the Festina Affair, cycling was rocked by the Operación Puerto doping scandal. And even today Operación Aderlass is uncovering new secrets.

Perhaps the Tour de France organisers were slightly hasty with their declarations of renewal.

Thank you for reading 5 articles in the past 30 days*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read any 5 articles for free in each 30-day period, this automatically resets

After your trial you will be billed £4.99 $7.99 €5.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just £49 $79 €59

Try your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

'The goal is to win the Tour de France' - Jai Hindley and new role with Primoz Roglic

From track spikes to bikes - Inside Jamaica's first-ever UCI cycling road race

Decluttering mass starts, rewarding podium riders top changes to 2024 Life Time Grand Prix

Most Popular

- Race Previews

- Race Reports

- Race Photos

- Tips & Reviews

Lore De Schepper Conquers Chambéry With Solo Triumph in 2024 Grand Prix de Chambéry

Tom pidcock finally wins amstel gold race sprint after previous near-miss, marianne vos secures victory in dramatic amstel gold race finale, live: 2024 women’s amstel gold race, women’s amstel gold race 2024 race preview.

Email: [email protected]

Flashback to the 1999 Tour de France

Mathew Mitchell

- Published on July 12, 2018

- in Men's Cycling

The 1999 Tour de France was labelled ‘the Tour of Renewal’ in reaction to the Festina Affair the year before. The 1999 Tour was supposed to be a new start after that doping scandal, however, the Tour de France was about to embark on a fresh decade of doping controversy.

Table of Contents

1993 World Champion Lance Armstrong was returning to the grandest stage of all after his recovery from cancer. A 4th place in the 1998 Vuelta made him one of the favourites for the 1999 Tour.

Tour de France 1999

- Mapei–Quick-Step

- ONCE–Deutsche Bank

- Saeco Macchine per Caffè–Cannondale

- Lotto–Mobistar

- Casino–Ag2r Prévoyance

- Mercatone Uno–Bianchi

- Kelme–Costa Blanca

- Vitalicio Seguros

- Team Telekom

- Crédit Agricole

- Festina–Lotus

- Cantina Tollo–Alexia Alluminio

- Française des Jeux

- U.S. Postal Service

- BigMat–Auber 93

- Lampre–Daikin

Tour de France 1999 Route

Passage du Gois

The Ile de Noirmoutier is a small island off the West of France, popular with tourists due to a temperate climate. The Tour de France has paid it several visits, kicking things off there in 2005 with a prologue (won at the time by David Zabriskie) and in a neat link to this year’s Tour , 2018 as well.

Since 1971, there’s been a perfectly good bridge between the Ile de Noirmoutier and mainland France but in 1999 they decided to use the bridge to cross over to the island, have a look round and then use the Passage du Gois to leave the island.

The Passage du Gois is a tidal causeway that is completely covered by water twice a day at high tide. Cars regularly drive over it between set times of day, with those leaving it late having to be brave (or foolhardy) to make it across. In 1999, the Tour de France raced over it during Stage 2 and whilst the rising tide wasn’t a problem, the effects of it were.

The road surface was very very slippy and ultimately a crash happened with 25 riders hitting the deck. Swiss rider Alex Zülle had been a pre-race favourite but got caught up in the crash and lost 6 minutes on the day – he ended up finishing 7 minutes behind ‘winner’ Lance Armstrong, but such was the US Postal rider’s domination this was good enough for 2nd place.

Despite this the Tour de France returned in 2011 , only this time it was at the start of the stage and neutralised behind the race director’s car.

Giuseppi Guerini vs. the Spectator

With a knee injury sidelining team-leader Jan Ullrich, Team Telekom’s aims were to ensure sprinter Erik Zabel won himself another Green Jersey. Super-domestique Giuseppe Guerini was able to have a free role in the mountains and go for stage victories. Guerini finished on the podium twice in the Giro, finishing 3rd each time. But he never managed higher than 20th in the Tour de France despite finishing in the top 30 on 6 Tours de France.

The 10th stage of the 1999 Tour de France was the iconic finish on Alpe d’Huez. Halfway up the Alpe, Guerini made a solo attack leaving the likes of Richard Virenque , Alex Zülle and Lance Armstrong behind – no mean feat. Pavel Tonkov tried to give chase but ended up in no man’s land between the two groups.

Shortly after Guerini had gone through the flamme rouge, a spectator decided they wanted a picture of this moment and popped out directly into Guerini’s path, causing both to fall to the ground.

Luckily Guerini was able to quickly hop back onto his bike and claim the stage win, just 21 seconds ahead of the chasing Tonkov. The main group of favourites were just 4 seconds behind him.

Christophe Bassons

The 1999 Tour de France saw the shunning of Christophe Bassons from the peloton. Bassons wrote some columns for Le Parisien throughout the Tour. This was as a result of the attention he’d received when declared a non-doper by other riders during the trials for the Festina Affair. Most of his columns were innocuous. But in one, he wrote that Lance Armstrong’s performances had shocked the peloton after his return to cycling from cancer.

On the same Stage 10 that saw Guerini get knocked off, the peloton had agreed to ride the first 100km slowly without telling Bassons. Bassons tried to get ahead of the peloton and form a break by himself. After letting him go, all of the teams then worked to bring him back quickly. The riders then passed him and stared. The only person who spoke to him was Lance Armstrong who offered the following advice:

” . . . and then Lance Armstrong reached me. He grabbed me by the shoulder, because he knew that everyone would be watching, and he knew that at that moment, he could show everyone that he was the boss. He stopped me, and he said what I was saying wasn’t true, what I was saying was bad for cycling, that I musn’t say it, that I had no right to be a professional cyclist, that I should quit cycling, that I should quit the tour, and finished by saying [*beep*] you.” – Bassons

Mostly shunned by other riders after this, the race director Jean-Marie Leblanc spoke out about him and members of his own team called him a coward. By the start of Stage 12, Bassons had gone home, unable to take the abuse the peloton was meting out to him.

The 1999 Tour de France has no winner. A result of the whitewashing of Lance Armstrong’s Tour de France history. Despite this, confirmed dopers Erik Zabel and Richard Virenque still have the Green and Polka Dot jerseys on their palmares. It linked the doping of the 1990s to the ongoing doping of the 2000s. A new generation finished on the podium in the years immediately after 1999. Riders like Andreas Klöden, Alexander Vinokourov, Joseba Beloki and the most staggering case, Raimondas Rumšas.

It took 15 years for Christophe Bassons to be vindicated, Lance Armstrong sat down with him and apologised for his actions. Bassons accepted, citing the fall-out that Armstrong experience once the USADA report confirmed his history of doping as penance enough. Tyler Hamilton later publicly apologised for his role but ultimately the real damage was done in 1999 when an innocent rider was pretty much hounded out of the sport.

The 1999 Tour de France was supposed to be the Tour of Renewal and in many ways, it was, just not how it was originally intended.

Related Posts

1999 Tour de France Stage #1

RBC Heritage: Main Feed + Scheffler Group (First Round)

The Chevron Championship: Khang & Nordqvist Featured Groups (First Round)

RBC Heritage: Finau & Day Featured Groups (First Round)

RBC Heritage: Featured Holes #4, #7, #14 & #17 (First Round)

Unsportsmanlike with Evan, Canty and Michelle Presented by Progressive

Sportscenter, florida: orange & blue game, acc huddle: nfl draft film breakdowns, ufc 290: volkanovski vs. rodriguez, cal poly vs. #16 texas, latest clips, tim legler: if i'm the knicks, i'm licking my chops to play 76ers, coby white puts up career-high 42 points in bulls win, 'this is gut-wrenching': coyotes players bid emotional farewell to arizona fans, 2024 nhl playoffs: the chase for the stanley cup is on, demar throws down emphatic one-handed dunk, dejounte murray skies for unreal poster slam, 76ers hold off heat, move on to face knicks, batum's 3-point shooting helps 76ers top heat, advance to face knicks, mike trout mashes 8th dinger of the season, stanton, judge fuel yankees' 9th-inning rally, nikita kucherov nhl's first to reach 100 points with 4-point performance, sixers' fans go wild for free chicken after heat's 2 missed fts, kevin hart wants nothing to do with d-wade's nba titles flex, stephen a.'s knicks hype has bob myers groaning, kyle schwarber clobbers 250th career home run, how real madrid overcame man city on pens to reach ucl semis, woj: jontay porter investigation remains open, stephen a.: lakers better show up vs. the nuggets, woj: zion injury is 'devastating news' for pelicans, belichick wishes this new rule was in effect when mcafee was playing, caitlin clark reveals her goals for rookie season with fever, bill belichick reveals to mcafee he's still studying film, how the alleged jontay porter gambling scandal got exposed, stephen a. can't help but laugh at stephen jones' cowboys comments, caitlin clark: i can't think of a better place to start my career, stephen a.: change is coming for the warriors, joel embiid gets surprised with his team usa jersey by grant hill, caitlin clark to mcafee: 'i was hoping the fever got the first pick', legler: klay thompson has been exposed the past 2 postseasons.

- Share full article

For more audio journalism and storytelling, download New York Times Audio , a new iOS app available for news subscribers.

Are ‘Forever Chemicals’ a Forever Problem?

The environmental protection agency says “forever chemicals” must be removed from tap water. but they lurk in much more of what we eat, drink and use..

This transcript was created using speech recognition software. While it has been reviewed by human transcribers, it may contain errors. Please review the episode audio before quoting from this transcript and email [email protected] with any questions.

From “The New York Times,” I’m Sabrina Tavernise. And this is “The Daily.”

[THEME MUSIC]

This month for the first time, the Environmental Protection Agency began to regulate a class of synthetic chemicals, known as forever chemicals, in America’s drinking water. But the chemicals, which have been linked to liver disease and other serious health problems, are in far more than just our water supply. Today, my colleague Kim Tingley explains.

It’s Wednesday, April 17.

So Kim, any time the EPA announces a regulation, I think we all sort of take notice because implicit in it is this idea that we have been exposed to something — something bad, potentially, lead or asbestos. And recently, the EPA is regulating a type of chemical known as PFAS So for those who don’t know, what are PFAS chemicals

Yeah, so PFAS stands for per and polyfluoroalkyl substances. They’re often called forever chemicals just because they persist so long in the environment and they don’t easily break down. And for that reason, we also use them in a ton of consumer products. They’re in makeup. They’re in carpet. They’re in nonstick cookware. They’re in food packaging, all sorts of things.

Yeah, I feel like I’ve been hearing about these chemicals actually for a very long time. I mean, nonstick pans, Teflon — that’s the thing that’s in my mind when I think PFAS.

Absolutely. Yeah, this class of chemicals has been around for decades. And what’s really important about this is that the EPA has decided, for the first time, to regulate them in drinking water. And that’s a ruling that stands to affect tens of millions of people.

So, help me understand where these things came from and how it’s taken so long to get to the point where we’re actually regulating them.

So, they really actually came about a long time ago. In 1938, DuPont, the people who eventually got us to Teflon, they were actually looking for a more stable kind of refrigerant. And they came upon this kind of chemical, PFAS. The thing that all PFAS chemicals have is a really strong bond between carbon atoms and fluorine atoms. This particular pairing is super strong and super durable.

They have water repellent properties. They’re stain resistant. They’re grease resistant. And they found a lot of uses for them initially in World War II. They were using them as part of their uranium enrichment process to do all these kinds of things. And then —

Well, good thing it’s Teflon.

In the 1950s is when they really started to come out as commercial products.

Even burned food won’t stick to Teflon. So it’s always easy to clean.

So, DuPont started using it in Teflon pans.

Cookware never needs scouring if it has DuPont Teflon.

And then another company, 3M also started using a kind of PFAS —

Scotchgard fabric protector. It keeps ordinary spills from becoming extraordinary stains.

— in one of their big products, Scotchgard. So you probably remember spraying that on your shoes if you want to make your shoes waterproof.

Use Scotchgard fabric protector and let your cup runneth over.

Right — miracle product, Scotchgard, Teflon. But of course, we’re talking about these chemicals because they’ve been found to pose health threats. When does that risk start to surface?

Yeah, so it’s pretty early on that DuPont and 3M start finding effects in animals in studies that they’re running in house.

Around the mid ‘60s, they start seeing that PFAS has an effect on rats. It’s increasing the liver and kidney weights of the rats. And so that seems problematic. And they keep running tests over the next decade and a half. And they try different things with different animals.

In one study, they gave monkeys really, really high levels of PFAS. And those monkeys died. And so they have a pretty strong sense that these chemicals could be dangerous. And then in 1979, they start to see that the workers that are in the plants manufacturing, working with these chemicals, that they’re starting to have higher rates of abnormal liver function. And in a Teflon plant, they had some pregnant workers that were working with these chemicals. And one of those workers in 1981 gave birth to a child who had some pretty severe birth defects.

And then by the mid 1980s, DuPont figures out that it’s not just their workers who are being exposed to these chemicals, but communities that are living in areas surrounding their Teflon plant, particularly the one in Parkersburg, West Virginia, that those communities have PFAS in their tap water.

Wow, so based on its own studies, DuPont knows its chemicals are making animals sick. They seem to be making workers sick. And now they found out that the chemicals have made their way into the water supply. What do they do with that information?

As far as we know, they didn’t do much. They certainly didn’t tell the residents of Parkersburg who were drinking that water that there was anything that they needed to be worried about.

How is that possible? I mean, setting aside the fact that DuPont is the one actually studying the health effects of its own chemicals, presumably to make sure they’re safe, we’ve seen these big, regulating agencies like the EPA and the FDA that exist in order to watch out for something exactly like this, a company that is producing something that may be harming Americans. Why weren’t they keeping a closer watch?

Yeah, so it goes kind of back to the way that we regulate chemicals in the US. It goes through an act called the Toxic Substances Control Act that’s administered by the EPA. And basically, it gives companies a lot of room to regulate themselves, in a sense. Under this act they have a responsibility to report to the EPA if they find these kinds of potential issues with a chemical. They have a responsibility to do their due diligence when they’re putting a chemical out into the environment.

But there’s really not a ton of oversight. The enforcement mechanism is that the EPA can find them. But this kind of thing can happen pretty easily where DuPont keeps going with something that they think might really be a problem and then the fine, by the time it plays out, is just a tiny fraction of what DuPont has earned from producing these chemicals. And so really, the incentive is for them to take the punishment at the end, rather than pull it out early.

So it seems like it’s just self-reporting, which is basically self-regulation in a way.

Yeah, I think that is the way a lot of advocacy groups and experts have characterized it to me, is that chemical companies are essentially regulating themselves.

So how did this danger eventually come to light? I mean, if this is in some kind of DuPont vault, what happened?

Well, there’s a couple different things that started to happen in the late ‘90s.

The community around Parkersburg, West Virginia, people had reported seeing really strange symptoms in their animals. Cows were losing their hair. They had lesions. They were behaving strangely. Some of their calves were dying. And a lot of people in the community felt like they were having health problems that just didn’t really have a good answer, mysterious sicknesses, and some cases of cancers.

And so they initiate a class action lawsuit against DuPont. As part of that class action lawsuit, DuPont, at a certain point, is forced to turn over all of their internal documentation. And so what was in the files was all of that research that we mentioned all of the studies about — animals, and workers, the birth defects. It was really the first time that the public saw what DuPont and 3M had already seen, which is the potential health harms of these chemicals.

So that seems pretty damning. I mean, what happened to the company?

So, DuPont and 3M are still able to say these were just a few workers. And they were working with high levels of the chemicals, more than a person would get drinking it in the water. And so there’s still an opportunity for this to be kind of correlation, but not causation. There’s not really a way to use that data to prove for sure that it was PFAS that caused these health problems.

In other words, the company is arguing, look, yes, these two things exist at the same time. But it doesn’t mean that one caused the other.

Exactly. And so one of the things that this class action lawsuit demands in the settlement that they eventually reach with DuPont is they want DuPont to fund a formal independent health study of the communities that are affected by this PFAS in their drinking water. And so they want DuPont to pay to figure out for sure, using the best available science, how many of these health problems are potentially related to their chemicals.

And so they ask them to pay for it. And they get together an independent group of researchers to undertake this study. And it ends up being the first — and it still might be the biggest — epidemiological study of PFAS in a community. They’ve got about 69,000 participants in this study.

Wow, that’s big.

It’s big, yeah. And what they ended up deciding was that they could confidently say that there was what they ended up calling a probable link. And so they were really confident that the chemical exposure that the study participants had experienced was linked to high cholesterol, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, testicular cancer, kidney cancer, and pregnancy induced hypertension.

And so those were the conditions that they were able to say, with a good degree of certainty, were related to their chemical exposure. There were others that they just didn’t have the evidence to reach a strong conclusion.

So overall, pretty substantial health effects, and kind of vindicates the communities in West Virginia that were claiming that these chemicals were really affecting their health.

Absolutely. And as the years have gone on, that was sort of just the beginning of researchers starting to understand all the different kinds of health problems that these chemicals could potentially be causing. And so since the big DuPont class action study, there’s really just been like this building and building and building of different researchers coming out with these different pieces of evidence that have accumulated to a pretty alarming picture of what some of the potential health outcomes could be.

OK, so that really kind of brings us to the present moment, when, at last, it seems the EPA is saying enough is enough. We need to regulate these things.

Yeah, it seems like the EPA has been watching this preponderance of evidence accumulate. And they’re sort of deciding that it’s a real health problem, potentially, that they need to regulate.

So the EPA has identified six of these PFAS chemicals that it’s going to regulate. But the concern that I think a lot of experts have is that this particular regulation is not going to keep PFAS out of our bodies.

We’ll be right back.

So, Kim, you just said that these regulations probably won’t keep PFAS chemicals out of our bodies. What did you mean?

Well, the EPA is talking about regulating these six kinds of PFAS. But there are actually more than 10,000 different kinds of PFAS that are already being produced and out there in the environment.

And why those six, exactly? I mean, is it because those are the ones responsible for most of the harm?

Those are the ones that the EPA has seen enough evidence about that they are confident that they are probably causing harm. But it doesn’t mean that the other ones are not also doing something similar. It’s just sort of impossible for researchers to be able to test each individual chemical compound and try to link it to a health outcome.

I talked to a lot of researchers who were involved in this area and they said that they haven’t really seen a PFAS that doesn’t have a harm, but they just don’t have information on the vast majority of these compounds.

So in other words, we just haven’t studied the rest of them enough yet to even know how harmful they actually are, which is kind of alarming.

Yeah, that’s right. And there’s just new ones coming out all the time.

Right. OK, so of the six that the EPA is actually intending to regulate, though, are those new regulations strict enough to keep these chemicals out of our bodies?

So the regulations for those six chemicals really only cover getting them out of the drinking water. And drinking water only really accounts for about 20 percent of a person’s overall PFAS exposure.

So only a fifth of the total exposure.

Yeah. There are lots of other ways that you can come into contact with PFAS. We eat PFAS, we inhale PFAS. We rub it on our skin. It’s in so many different products. And sometimes those products are not ones that you would necessarily think of. They’re in carpets. They’re in furniture. They’re in dental floss, raincoats, vinyl flooring, artificial turf. All kinds of products that you want to be either waterproof or stain resistant or both have these chemicals in them.

So, the cities and towns are going to have to figure out how to test for and monitor for these six kinds of PFAS. And then they’re also going to have to figure out how to filter them out of the water supply. I think a lot of people are concerned that this is going to be just a really expensive endeavor, and it’s also not really going to take care of the entire problem.

Right. And if you step back and really look at the bigger problem, the companies are still making these things, right? I mean, we’re running around trying to regulate this stuff at the end stage. But these things are still being dumped into the environment.

Yeah. I think it’s a huge criticism of our regulatory policy. There’s a lot of onus put on the EPA to prove that a harm has happened once the chemicals are already out there and then to regulate the chemicals. And I think that there’s a criticism that we should do things the other way around, so tougher regulations on the front end before it goes out into the environment.

And that’s what the European Union has been doing. The European Chemicals Agency puts more of the burden on companies to prove that their products and their chemicals are safe. And the European Chemicals Agency is also, right now, considering just a ban on all PFAS products.

So is that a kind of model, perhaps, of what a tough regulation could look like in the US?

There’s two sides to that question. And the first side is that a lot of people feel like it would be better if these chemical companies had to meet a higher standard of proof in terms of demonstrating that their products or their chemicals are going to be safe once they’ve been put out in the environment.

The other side is that doing that kind of upfront research can be really expensive and could potentially limit companies who are trying to innovate in that space. In terms of PFAS, specifically, this is a really important chemical for us. And a lot of the things that we use it in, there’s not necessarily a great placement at the ready that we can just swap in. And so it’s used in all sorts of really important medical devices or renewable energy industries or firefighting foam.

And in some cases, there are alternatives that might be safer that companies can use. But in other cases, they just don’t have that yet. And so PFAS is still really important to our daily lives.

Right. And that kind of leaves us in a pickle because we know these things might be harming us. Yet, we’re kind of stuck with them, at least for now. So, let me just ask you this question, Kim, which I’ve been wanting to ask you since the beginning of this episode, which is, if you’re a person who is concerned about your exposure to PFAS, what do you do?

Yeah. So this is really tricky and I asked everybody this question who I talked to. And everybody has a little bit of a different answer based on their circumstance. For me what I ended up doing was getting rid of the things that I could sort of spot and get rid of. And so I got rid of some carpeting and I checked, when I was buying my son a raincoat, that it was made by a company that didn’t use PFAS.

It’s also expensive. And so if you can afford to get a raincoat from a place that doesn’t manufacture PFAS, it’s going to cost more than if you buy the budget raincoat. And so it’s kind of unfair to put the onus on consumers in that way. And it’s also just not necessarily clear where exactly your exposure is coming from.

So I talk to people who said, well, it’s in dust, so I vacuum a lot. Or it’s in my cleaning products, so I use natural cleaning products. And so I think it’s really sort of a scattershot approach that consumers can take. But I don’t think that there is a magic approach that gets you a PFAS-free life.

So Kim, this is pretty dark, I have to say. And I think what’s frustrating is that it feels like we have these government agencies that are supposed to be protecting our health. But when you drill down here, the guidance is really more like you’re on your own. I mean, it’s hard not to just throw up your hands and say, I give up.

Yeah. I think it’s really tricky to try to know what you do with all of this information as an individual. As much as you can, you can try to limit your individual exposure. But it seems to me as though it’s at a regulatory level that meaningful change would happen, and not so much throwing out your pots and pans and getting new ones.

One thing about PFAS is just that we’re in this stage still of trying to understand exactly what it’s doing inside of us. And so there’s a certain amount of research that has to happen in order to both convince people that there’s a real problem that needs to be solved, and clean up what we’ve put out there. And so I think that we’re sort of in the middle of that arc. And I think that that’s the point at which people start looking for solutions.

Kim, thank you.

Here’s what else you should know today. On Tuesday, in day two of jury selection for the historic hush money case against Donald Trump, lawyers succeeded in selecting 7 jurors out of the 12 that are required for the criminal trial after failing to pick a single juror on Monday.

Lawyers for Trump repeatedly sought to remove potential jurors whom they argued were biased against the president. Among the reasons they cited were social media posts expressing negative views of the former President and, in one case, a video posted by a potential juror of New Yorkers celebrating Trump’s loss in the 2020 election. Once a full jury is seated, which could come as early as Friday, the criminal trial is expected to last about six weeks.

Today’s episode was produced by Clare Toeniskoetter, Shannon Lin, Summer Thomad, Stella Tan, and Jessica Cheung, with help from Sydney Harper. It was edited by Devon Taylor, fact checked by Susan Lee, contains original music by Dan Powell, Elisheba Ittoop, and Marion Lozano, and was engineered by Chris Wood.

Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly.

That’s it for The Daily. I’m Sabrina Tavernise. See you tomorrow.

- April 18, 2024 • 30:07 The Opening Days of Trump’s First Criminal Trial

- April 17, 2024 • 24:52 Are ‘Forever Chemicals’ a Forever Problem?

- April 16, 2024 • 29:29 A.I.’s Original Sin

- April 15, 2024 • 24:07 Iran’s Unprecedented Attack on Israel

- April 14, 2024 • 46:17 The Sunday Read: ‘What I Saw Working at The National Enquirer During Donald Trump’s Rise’

- April 12, 2024 • 34:23 How One Family Lost $900,000 in a Timeshare Scam

- April 11, 2024 • 28:39 The Staggering Success of Trump’s Trial Delay Tactics

- April 10, 2024 • 22:49 Trump’s Abortion Dilemma

- April 9, 2024 • 30:48 How Tesla Planted the Seeds for Its Own Potential Downfall

- April 8, 2024 • 30:28 The Eclipse Chaser

- April 7, 2024 The Sunday Read: ‘What Deathbed Visions Teach Us About Living’

- April 5, 2024 • 29:11 An Engineering Experiment to Cool the Earth

Hosted by Sabrina Tavernise

Featuring Kim Tingley

Produced by Clare Toeniskoetter , Shannon M. Lin , Summer Thomad , Stella Tan and Jessica Cheung

With Sydney Harper

Edited by Devon Taylor

Original music by Dan Powell , Elisheba Ittoop and Marion Lozano

Engineered by Chris Wood

Listen and follow The Daily Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

The Environmental Protection Agency has begun for the first time to regulate a class of synthetic chemicals known as “forever chemicals” in America’s drinking water.

Kim Tingley, a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine, explains how these chemicals, which have been linked to liver disease and other serious health problems, came to be in the water supply — and in many more places.

On today’s episode

Kim Tingley , a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine.

Background reading

“Forever chemicals” are everywhere. What are they doing to us?

The E.P.A. issued its rule about “forever chemicals” last week.

There are a lot of ways to listen to The Daily. Here’s how.

We aim to make transcripts available the next workday after an episode’s publication. You can find them at the top of the page.

Fact-checking by Susan Lee .

The Daily is made by Rachel Quester, Lynsea Garrison, Clare Toeniskoetter, Paige Cowett, Michael Simon Johnson, Brad Fisher, Chris Wood, Jessica Cheung, Stella Tan, Alexandra Leigh Young, Lisa Chow, Eric Krupke, Marc Georges, Luke Vander Ploeg, M.J. Davis Lin, Dan Powell, Sydney Harper, Mike Benoist, Liz O. Baylen, Asthaa Chaturvedi, Rachelle Bonja, Diana Nguyen, Marion Lozano, Corey Schreppel, Rob Szypko, Elisheba Ittoop, Mooj Zadie, Patricia Willens, Rowan Niemisto, Jody Becker, Rikki Novetsky, John Ketchum, Nina Feldman, Will Reid, Carlos Prieto, Ben Calhoun, Susan Lee, Lexie Diao, Mary Wilson, Alex Stern, Dan Farrell, Sophia Lanman, Shannon Lin, Diane Wong, Devon Taylor, Alyssa Moxley, Summer Thomad, Olivia Natt, Daniel Ramirez and Brendan Klinkenberg.

Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly. Special thanks to Sam Dolnick, Paula Szuchman, Lisa Tobin, Larissa Anderson, Julia Simon, Sofia Milan, Mahima Chablani, Elizabeth Davis-Moorer, Jeffrey Miranda, Renan Borelli, Maddy Masiello, Isabella Anderson and Nina Lassam.

Advertisement

- Tour de France

- Giro d'Italia

- La Vuelta ciclista a España

- World Championships

- Amstel Gold Race

- Milano-Sanremo

- Tirreno-Adriatico

- Liège-Bastogne-Liège

- Il Lombardia

- La Flèche Wallonne

- Paris - Nice

- Paris-Roubaix

- Volta Ciclista a Catalunya

- Critérium du Dauphiné

- Tour des Flandres

- Gent-Wevelgem in Flanders Fields

- Clásica Ciclista San Sebastián

- INEOS Grenadiers

- Groupama - FDJ

- EF Education-EasyPost

- Decathlon AG2R La Mondiale Team

- BORA - hansgrohe

- Bahrain - Victorious

- Astana Qazaqstan Team

- Intermarché - Wanty

- Lidl - Trek

- Movistar Team

- Soudal - Quick Step

- Team dsm-firmenich PostNL

- Team Jayco AlUla

- Team Visma | Lease a Bike

- UAE Team Emirates

- Arkéa - B&B Hotels

- Alpecin-Deceuninck

- Grand tours

- Countdown to 3 billion pageviews

- Favorite500

- Profile Score

- Stage winners

- All stage profiles

- Race palmares

- Complementary results

- Finish photo

- Contribute info

- Contribute results

- Contribute site(s)

- Results - Results

- Info - Info

- Live - Live

- Game - Game

- Stats - Stats

- More - More

- »

Sprint | La Fl

Sprint | neuill, sprint | ch, finishline points, kom sprint | côte de beaumont-la-ronce, team day classification, race information.

- Date: 07 July 1999

- Start time: -

- Avg. speed winner: 50.36 km/h

- Race category: ME - Men Elite

- Distance: 194.5 km

- Points scale: GT.A.Stage

- Parcours type:

- ProfileScore: 16

- Vert. meters: 1158

- Departure: Laval

- Arrival: Blois

- Race ranking: 0

- Startlist quality score: 1255

- Won how: Sprint of large group

- Avg. temperature:

Grand Tours

- Vuelta a España

Major Tours

- Volta a Catalunya

- Tour de Romandie

- Tour de Suisse

- Itzulia Basque Country

- Milano-SanRemo

- Ronde van Vlaanderen

Championships

- European championships

Top classics

- Omloop Het Nieuwsblad

- Strade Bianche

- Gent-Wevelgem

- Dwars door vlaanderen

- Eschborn-Frankfurt

- San Sebastian

- Bretagne Classic

- GP Montréal

Popular riders

- Tadej Pogačar

- Wout van Aert

- Remco Evenepoel

- Jonas Vingegaard

- Mathieu van der Poel

- Mads Pedersen

- Primoz Roglic

- Demi Vollering

- Lotte Kopecky

- Katarzyna Niewiadoma

- PCS ranking

- UCI World Ranking

- Points per age

- Latest injuries

- Youngest riders

- Grand tour statistics

- Monument classics

- Latest transfers

- Favorite 500

- Points scales

- Profile scores

- Reset password

- Cookie consent

About ProCyclingStats

- Cookie policy

- Contributions

- Pageload 0.0916s

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The 1999 Tour de France was a multiple stage bicycle race held from 3 to 25 July, and the 86th edition of the Tour de France.It has no overall winner—although American cyclist Lance Armstrong originally won the event, the United States Anti-Doping Agency announced in August 2012 that they had disqualified Armstrong from all his results since 1998, including his seven consecutive Tour de ...

1999 Tour de France Quick Facts: 3,686.8 km, traveled at a then record average speed of 40.276 km/hr. 180 starters and 141 classified finishers. Erik Zabel wins his 4th Green Jersey for best sprinter. Richard Virenque wins his 5th Polka Dot Jersey for best climber.

The 1999 Tour de France was dubbed the 'Tour of Renewal' (Image credit: Getty Images Sport) Twenty years ago, the Tour de France was vaunted by the organisers as 'The Tour of Renewal'. It was 12 ...

Competing teams and riders for Tour de France 1999. Top competitors are Erik Zabel, Alex Zülle and Robbie McEwen.

In the 1999 Tour de France, the following 20 teams were each allowed to field nine cyclists:. After the doping controversies in the 1998 Tour de France, the Tour organisation banned some persons from the race, including cyclist Richard Virenque, Laurent Roux and Philippe Gaumont, manager Manolo Saiz and the entire TVM-Farm Frites team. Virenque's team Polti then appealed at the UCI against ...

The 1999 Tour de France was a multiple stage bicycle race held from 3 to 25 July, and the 86th edition of the Tour de France. It has no overall winner—although American cyclist Lance Armstrong originally won the event, the United States Anti-Doping Agency announced in August 2012 that they had disqualified Armstrong from all his results since 1998, including his seven consecutive Tour de ...

Lance Armstrong is the winner of Tour de France 1999, before Alex Zülle and Fernando Escartín. Robbie McEwen is the winner of the final stage.

Prologue » Puy-du-Fou › Puy-du-Fou (6.8km) Prol. Lance Armstrong is the winner of Tour de France 1999 Prologue, before Alex Zülle and Abraham Olano. Lance Armstrong was leader in GC.

The 1999 Tour de France was the 86th edition of Tour de France, one of cycling's Grand Tours. The Tour began in Le Puy du Fou with a prologue individual time trial on 3 July and Stage 11 occurred on 15 July with a hilly stage from Le Bourg-d'Oisans.

The 1999 Tour de France has no winner. A result of the whitewashing of Lance Armstrong's Tour de France history. Despite this, confirmed dopers Erik Zabel and Richard Virenque still have the Green and Polka Dot jerseys on their palmares. It linked the doping of the 1990s to the ongoing doping of the 2000s.

Tour de France, Grand Tour France, July 3-25, 1999 Main Page Stage 9 Results ... Tour de France: 5th participation. 5 stage victories (Verdun 1993, Limoges 1995, Prologue Puy-du-Fou, ITT Metz, and Sestrières 1999). 3 abandons (1993, 1994, 1996). 36th in 1995.

Stage 2 » Challans › Saint-Nazaire (176km) Tom Steels is the winner of Tour de France 1999 Stage 2, before Jaan Kirsipuu and Mario Cipollini. Jaan Kirsipuu was leader in GC.

The 1999 Tour de France was a multiple stage bicycle race held from 3 to 25 July, and the 86th edition of the Tour de France. It has no overall winner—althou...

Tour de France, Grand Tour France, July 3-25, 1999 Main Page Stage 18 Results Stage 18, Jonzac - Futuroscope, 182 kms: ... were 2 French riders in the leading group and this was welcome in a country that has peformed poorly in this year's Tour. The average speed was 46.1 km/h for the second hour and 41.8 km/h for the race to date.

The Tour de France opened July 3, 1999, and ran through July 25. Armstrong won the prologue, but a few days later, he received notice of a positive test for a corticosteroid, a chemical that helps ...

1999 Tour de France - Stages 9 and 10 Eurosport coverage with commentary by David Duffield, Stephen Roche and Russell Williams.Note: This video was created b...

The 1999 Tour de France was the 86th edition of Tour de France, one of cycling's Grand Tours. The Tour began in Le Puy du Fou with a prologue individual time trial on 3 July and Stage 10 occurred on 14 July with a mountainous stage to Alpe d'Huez. The race finished on the Champs-Élysées in Paris on 25 July.