The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

Hospital Emergency Room Visits per 1,000 Population by Ownership Type

Data are loading.

- Hospital Utilization

- HEDIS Measures and Technical Resources

- Emergency Department Utilization

Emergency Department Utilization (EDU)

Assesses emergency department (ED) utilization among commercial (18 and older) and Medicare (18 and older) health plan members. Plans report observed rates of ED use and a predicted rate of ED use based on the health of the member population. The observed and expected rates are used to calculate a calibrated observed-to-expected ratio that assesses whether plans had more, the same or less emergency department visits than expected, while accounting for incremental improvements across all plans over time. The observed-to-expected ratio is multiplied by the emergency department visit rate across all health plans to produce a risk-standardized rate which allows for national comparison.

Why It Matters

ED visits are a high-intensity service and a cost burden on the health care system, as well as on patients. Some ED events may be attributed to preventable or treatable conditions . A high rate of ED utilization may indicate poor care management, inadequate access to care or poor patient choices, resulting in ED visits that could be prevented. 1,2 Plans can ensure that members receive appropriate, coordinated primary care to address preventable ED visits.

Results – National Averages

Emergency department utilization total rate.

*Lower rates signify better performance.

§ Not available due to CMS suspension of data reporting during COVID-19 pandemic.

This State of Healthcare Quality Report classifies health plans differently than NCQA’s Quality Compass. HMO corresponds to All LOBs (excluding PPO and EPO) within Quality Compass. PPO corresponds to PPO and EPO within Quality Compass.

Figures do not account for changes in the underlying measure that could break trending. Contact Information Products via my.ncqa.org for analysis that accounts for trend breaks.

- Dowd, B., M. Karmarker, T. Swenson, et al. 2014. “Emergency department utilization as a measure of physician performance.” American Journal of Medical Quality 29 (2), 135–43. http://ajm.sagepub.com/content/29/2/135.long

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015. Measures of Care Coordination: Preventable Emergency Department Visits. Accessed at https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/chartbooks/carecoordination/measure2.html

Save your favorite pages and receive notifications whenever they’re updated.

You will be prompted to log in to your NCQA account.

Share this page with a friend or colleague by Email.

We do not share your information with third parties.

Print this page.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Popul Health Manag

Comparing Emergency Department Use Among Medicaid and Commercial Patients Using All-Payer All-Claims Data

Hyunjee kim.

1 Center for Health Systems Effectiveness, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon.

K. John McConnell

Benjamin c. sun.

2 Department of Emergency Medicine, Center of Policy Research–Emergency Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon.

Associated Data

The high rate of emergency department (ED) use by Medicaid patients is not fully understood. The objective of this paper is (1) to provide context for ED service use by comparing Medicaid and commercial patients' differences across ED and non-ED health service use, and (2) to assess the extent to which Medicaid–commercial differences in ED use can be explained by observable factors in administrative data. Statistical decomposition methods were applied to ED, mental health, and inpatient care using 2011–2013 Medicaid and commercial insurance claims from the Oregon All Payer All Claims database. Demographics, comorbidities, health services use, and neighborhood characteristics accounted for 44% of the Medicaid–commercial difference in ED use, compared to 83% for mental health care and 75% for inpatient care. This suggests that relative to mental health and inpatient care, a large portion of ED use cannot be explained by administrative data. Models that further accounted for patient access to different primary care physicians explained an additional 8% of the Medicaid–commercial difference in ED use, suggesting that the quality of primary care may influence ED use. The remaining unexplained difference suggests that appropriately reducing ED use remains a credible target for policy makers, although success may require knowledge about patients' perceptions and behaviors as well as social determinants of health.

Introduction

T he high rate of emergency department (ED) use by Medicaid enrollees has been a long-standing concern among policy makers. 1–4 State Medicaid programs have proposed different policies to reduce ED visits including requiring Medicaid patients to make higher co-payments for their ED visits or providing Medicaid patients with robust alternative services to ED care through patient-centered medical home models. 5 However, those policies may have limited effectiveness if they are based on incorrect assumptions about the underlying reasons for high rates of ED use in the Medicaid population.

A variety of factors may explain differences in ED use among Medicaid and commercial patients. Medicaid enrollees have a higher comorbidity burden 1 , 6 , 7 and are more likely to experience primary care access problems or unsatisfactory primary care. 6 , 8 , 9 Medicaid enrollees also might use the ED more frequently because they typically make minimal co-payments for ED visits, 1 or because they perceive the ED as a one-stop shop that provides multiple services simultaneously, an attribute appealing for patients who struggle with transportation. 10

There are several gaps in the knowledge of ED use among Medicaid beneficiaries. First, although high ED use is a visible target for policy makers, less is known about whether the Medicaid–commercial utilization difference is unique to the ED or if it persists across other types of health services. Second, although some studies have used survey data to explain the Medicaid–commercial difference in ED use, there have been fewer efforts to assess the extent to which ED use could be explained by Medicaid–commercial differences in observable factors such as patient demographics, comorbidities, neighborhoods, and proximities to services to explain differences. Third, although high ED use has often been viewed as a proxy for a lack of access to primary care, most studies have not been able to assess the impacts of different care by different primary care providers (PCPs). The final question is important because simple measures of primary care access may obscure differences in the quality or thoroughness of care by PCPs.

This study bridges these gaps using Oregon's All Payer All Claims (APAC) database. These data allow for 3 contributions that are highly relevant to policy development around ED use. First, APAC data allow for the observation of Medicaid and commercial patients' differences in utilization not only in ED care, but in other services as well. Second, these data allowed the assessment of whether Medicaid and commercial differences in ED use are consistent across different types of ED visits, including low- and high-severity ED visits. These analyses may help elucidate policies that are more effective in reducing ED visits for primary care treatable conditions. Third, by using provider identification information for each claim in the data, this study examined the influence of each Medicaid and commercial patient's PCP on ED use. These analyses are particularly valuable because PCPs may differ in their efforts or capacity to help patients receive the care they need without using the ED.

In sum, this study compared ED use by Medicaid and commercially insured patients. These groups account for the largest shares of ED patients aged 18 to 64 years. 2 , 11 Specifically, this study aims to: (1) provide context for ED service use by comparing Medicaid–commercial differences across ED and non–ED health service use, and (2) assess the extent to which differences in ED use by Medicaid and commercial patients can be explained by observable factors.

Study design

This study implemented the non-linear Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition of Medicaid–commercial differences in ED visits using 2011 to 2013 data from the Oregon APAC database. 12 More specific explanation of the non-linear Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition methods will be provided in the primary data analysis section. The APAC data include all Medicaid and commercially insured enrollees residing in Oregon and their medical claims. The exception is enrollees in commercial self-insured plans that cover fewer than 5000 enrollees; the APAC database includes approximately 87% of commercially-insured individuals in the state. 13 Claims related to substance abuse were excluded to comply with federal regulations. 14 Institutional review board approval for this study was received from Oregon Health & Science University.

Selection of participants

This study included all Medicaid and commercially-insured enrollees extracted from the 2011–2013 data from the Oregon APAC database. Children aged 0–18 years were excluded because pediatric ED visits are likely to be highly correlated with parent ED visit behaviors. 1 Further exclusions were enrollees who were ages 65 years or older or were eligible for Medicare because no information was available on health service use paid by Medicare, and enrollees who were not covered by Medicaid or commercial insurance throughout each entire calendar year because changes in insurance status may be associated with changes in ED utilization patterns. 13 The final data set included 2,586,173 patient-year observations, with Medicaid beneficiaries accounting for 13.2% of the total sample. See Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Data are available in the online article at www.liebertpub.com/pop ) for characteristics of beneficiaries in the sample.

Outcome measures

The outcome variables included dummy variables indicating whether a patient used ED care, mental health care, and inpatient care at least once during the year. In addition, 3 separate types of ED visits were examined: (1) ED visits that resulted in an inpatient admission to the hospital, (2) high-severity ED visits, and (3) low-severity ED visits. Note that these are not mutually exclusive categories. High- and low-severity ED visits were constructed based on the algorithm developed by Billings et al. 15 The algorithm calculates probabilities for 4 categories based on each visit's primary diagnosis: non-emergent; emergent yet primary care treatable; emergent and ED care needed yet preventable; and emergent and ED care needed and not preventable. A visit was defined as high severity if the sum of the probabilities of the last 2 categories was at least 0.75 and low severity if the sum was less than 0.25, an approach validated in other studies. 16–19 These severity categories were not used to assess the appropriateness of ED visits, but rather to identify ED visits that could have been treated in a primary care setting. ED visits with injury and mental health diagnoses were not captured with the algorithm and were excluded in defining low- and high-severity ED visits. Supplementary Table S2 lists the 5 most common primary diagnoses for each type of ED visit across Medicaid and commercial insurance patients. As a sensitivity analysis, an indeterminate-severity ED visit (a visit with the sum of the probabilities between 0.25 and 0.75) 16–18 was created and the same analysis was conducted.

Observable factors

Each patient's age, sex, and rurality (based on zip code of residence) were considered to be potential contributing factors to the Medicaid–commercial difference in ED visits. 20 Also taken into account were each patient's health conditions, including pregnancy status and 17 chronic health conditions. The health conditions were extracted from the Chronic Illness and Disability Payment System (CDPS), which has been validated and used for risk adjustment in Medicaid populations. 21 , 22 Patients' health service use also was considered, including whether each received primary care and mental health care at least once a year.

Observable factors also included patients' neighborhood characteristics, including percentages of the population below the poverty level, college graduates, and African American and Hispanic residents based on zip code of residence, extracted from the 2011 American Community Survey. 23 For a proxy measure of access to primary and specialty care, this study used the number of primary care and specialty physicians per patient in each patient's hospital service area, extracted from the Area Health Resources File. 24 To control for access to the ED, the distance in miles from the patient's residence to the nearest ED was calculated using zip codes and an indicator of ≥25 miles distance to the nearest ED was created. Finally, year dummies were included to control for changes in ED visits over time.

Primary data analysis

A non-linear version of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition was used to analyze the influence of each observable factor on the Medicaid–commercial difference in ED visits. 25 The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition has been widely used to explain differences between groups, including the wage difference between whites and blacks, the health insurance coverage difference across children with different ethnicities, and specialty care referral differences between men and women. 26–28

This technique was used to decompose the Medicaid–commercial difference in the average level of ED use into 2 parts. The first part ( explained difference ) is the difference in ED use attributable to differences in factors across Medicaid and commercial patients that are observable in the APAC database. These observable factors include patients' demographics, health conditions, neighborhood characteristics, distance to the nearest ED, and selection of PCPs. This first part enables the analysis of the relative contribution of each observable factor to the difference in ED use.

The second part ( unexplained difference ) is the difference in ED use not captured by observable factors. The second part captures factors affecting ED use that cannot be observed in the database, such as unobserved differences in behavior between Medicaid and commercial enrollees or differences in providers' treatment of Medicaid versus commercial patients. For example, Medicaid patients' tendency to use the ED as a “one-stop health care shop” would be captured as a part of the unexplained difference.

Because of the binary nature of the outcome variables, a non-linear version of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition was used, the Fairlie decomposition. 25 Both Medicaid and commercial patients were used and a logit regression of their ED use was estimated. The contribution of each factor was then calculated using coefficients from the logit regression with observable factors randomly ordered. As a sensitivity analysis, coefficients from 2 separate regressions were used with a separate sample of Medicaid and commercial groups and the relative contribution of each factor was calculated.

Three sets of decomposition analyses were conducted. The first examined the influence of observable factors on multiple types of health service use by Medicaid and commercial patients. The outcome measures for these analyses included any ED, mental health, and inpatient use at least once a year. These analyses enabled the assessment of whether a large difference in ED use by Medicaid and commercial patients is also seen in other services. Primary care use was not examined in this analysis because the Medicaid–commercial difference in any primary care use was negligible (less than 1 percentage point). The second set of analyses switched the focus to ED care and examined the extent to which observable factors explained the Medicaid–commercial difference in ED visits including any ED visits, high-severity, low-severity, and ED visits resulting in an inpatient admission.

The third set of analyses included PCP “fixed effects” as another observable factor in the model to examine the relative importance of each patient's choice of specific PCP on the patient's ED visits. This fixed effects model included a dummy variable for each separate PCP (identified through the National Provider Identifier). In this manner, the model controlled for unobserved factors specific to each patient's PCP, going beyond a simple measure of access to primary care. For example, Medicaid patients might have access to primary care but be cared for by low-quality providers, leading patients to visit the ED even for primary care treatable conditions. Provider identification information was used to assign 1 PCP to each patient. For patients who visited multiple PCPs a year, the PCP a patient visited the most was selected. Only those PCPs who treated at least 150 patients a year were included to avoid perfect prediction in logit regressions. Based on these additional sample selection criteria, 772,143 patient-year observations treated by 1283 PCPs were used for the third analysis. As another sensitivity analysis, this sample's ED utilization was compared that of the original sample.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Table 1 displays the results of the decomposition analyses for different health services. The first 2 rows display the probability that Medicaid and commercial patients used each type of health care at least once a year. The Medicaid–commercial difference in ED visits was substantially greater than the difference in mental health and inpatient care. A substantial difference also was found in what observable factors could explain in the difference in ED use as compared to other services. Observable characteristics explained only 43.8% of the difference in ED visits while the corresponding values for mental health and inpatient care were 82.6% and 74.7%, respectively.

Decomposition Analysis of Difference in Use of Emergency Department, Mental Health, and Inpatient Care Between Medicaid and Commercial Patients (n = 2,586,173)

ED, emergency department.

The first 2 rows in Table 2 display descriptive statistics for Medicaid and commercially insured adults' ED visits. Approximately 44.5% of Medicaid patients visited the ED at least once a year, about 4 times more than commercial patients. This gap was greater than the national average in 2013, when 38.0% and 14.1% of Medicaid and commercial patients, respectively, visited the ED. 2 Medicaid patients were 7 times more likely to have a low-severity ED visit and 4 times more likely to have a high-severity ED visit or ED visit resulting in an inpatient admission.

Decomposition Analysis of Difference in Emergency Department Visits Between Medicaid and Commercial Patients (Pooled Coefficient) (n = 2,586,173)

CDPS, Chronic Illness and Disability Payment System; ED, emergency department; PCP, primary care provider.

The top reasons for each type of ED visits were similar between Medicaid and commercial patients ( Supplementary Table S2 ). The most common health conditions for low-severity ED visits include headache, back pain, and nausea/vomiting, which could possibly be managed in primary care settings. In contrast, emergent health conditions such as urinary tract stones and cardiac dysrhythmia were the main diagnosis for high-severity visits.

The remaining rows in Table 2 display detailed decomposition results for various types of ED visits, showing the relative contribution of each observable factor to the difference in ED visits between Medicaid and commercial patients. For simplicity, only the relative contribution of each factor in percentage terms is reported. Supplementary Table S4 provides the complete set of decomposition estimates and their standard errors. Supplementary Table S3 provides logit regression estimates used to calculate decomposition estimates in Supplementary Table S4 .

Observable factors explained 15 out of 34 percentage points of total difference in any ED visit, indicating that less than a half (15/34 × 100 = 43.8%) of the Medicaid–commercial difference in any ED visits was explained by observable factors. The Medicaid–commercial difference in age composition explained 0.0215 out of the total 0.34 percentage point difference in any ED visits ( Supplementary Table S4 ), indicating that 6.4% of the total difference in ED visits (0.0215/0.34 × 100≈6.4%) was explained by differences in age composition. As another example, the Medicaid–commercial difference in the distance to the nearest ED (≥25 miles to ED) explained −0.0004 of the total difference in any ED visits, explaining −0.1% of the difference in ED visits (−0.0004/0.34 × 100≈−0.1%). This negative value indicates that Medicaid patients' further distance from the ED (as compared to commercial patients') was actually associated with lower rates of ED visits.

Health conditions measured by CDPS indicators explained the greatest amount (30.3%) of the Medicaid–commercial differential. Primary care visits explained only a small portion of the difference in ED use (0.3%), perhaps because Medicaid and commercial patients had similar rates of primary care use. Neighborhood characteristics and provider availability explained less than 4% of the difference.

The total differences for high-severity and inpatient visits were relatively small (0.040 and 0.041 percentage points, respectively) compared to the difference for any low-severity visits (0.22 percentage points). Observable factors explained a greater portion of the difference in high-severity and ED visits resulting in inpatient admissions (73.0% and 86.7%, respectively) than low-severity ED visits (47.7%). The prevalence of health conditions, as captured by the CDPS indicators, explained the largest proportion of differences in use.

Table 3 displays decomposition results with and without PCP fixed effects. This analysis restricted the sample to patients with at least 1 primary care visit and decomposed the Medicaid–commercial difference, controlling for each patient's specific PCP. Inclusion of PCP fixed effects increased the share of the explained Medicaid–commercial difference for any ED visit by 8.1%, from 49.6% without fixed effects to 57.7% with fixed effects. A similar phenomenon was found for low-severity ED visits, with the explained share increasing by 8.7%, from 53.4% without fixed effects to 62.1% with fixed effects. By contrast, the inclusion of PCP fixed effects increased the explained share for high-severity ED visits by only 1.5 percentage points and decreased the explained share by 0.5% for ED visits resulting in an inpatient admission. In sum, each patient's selection of PCP explained a greater portion of the difference in low-severity ED visits than in high-severity ED visits or those resulting in an inpatient admission. Supplementary Tables S5 and S6 provide the full decomposition results for these models.

Decomposition Analysis of Differences in Emergency Department Visit Between Medicaid and Commercial Patients with Primary Care Provider Fixed Effects Included and Excluded on the Restricted Sample (n = 772,143)

ED, emergency department; PCP, primary care provider.

As a sensitivity analysis, the same decomposition analysis was conducted for any indeterminate ED visit ( Supplementary Table S7 ). Results revealed that observed factors explained 58.9% of the Medicaid–commercial difference, which was between explained shares for high- and low-severity ED visits. Another sensitivity analysis used coefficients from the regression with a separate sample of Medicaid and commercial insurance enrollees for decomposition and found that the basic patterns stayed the same ( Supplementary Tables S8 and S9 ). Finally, a subset of patients included in the decomposition with PCP fixed effects was examined and it was found that they had similar ED use patterns ( Supplementary Table S6 ).

Using newly available APAC data, this study found that the Medicaid–commercial difference in ED care was substantially greater than the difference in mental health and inpatient care, further highlighting the disproportionately high rates of ED use among Medicaid patients. Decomposition methods could explain the majority of the Medicaid–commercial difference for mental health and inpatient care services, but ED care was an exception. In other words, unobserved factors played a more important role in explaining ED use than other services among Medicaid patients.

Among observable factors, health conditions explained the greatest portion of the difference in any ED visits. This result suggests that effective interventions to reduce ED visits among Medicaid enrollees would include providing alternative health services for enrollees with health conditions such as case management, regular primary care, and access to urgent care. With the exception of age, other demographic factors accounted for relatively little of the difference in ED use. Given that the youngest group of enrollees' (aged 19 to 24 years) had the highest likelihood of ED visits ( Supplementary Table S3 ), and that a large amount of the ED use difference was explained by patients' age, the ED use patterns of younger Medicaid enrollees deserves particular attention.

The amount of the difference explained by observable factors was substantially higher for high-severity ED visits and those resulting in an inpatient admission than for low-severity visits. That is, unobservable factors were more likely to drive low-severity ED visits as compared to other types of ED visits. This discrepancy was primarily driven by the greater relevance of CDPS risk indicators in explaining high-severity and inpatient visits. In other words, the Medicaid–commercial difference in health conditions was a considerably more important factor for high-severity ED visits and those resulting in an inpatient admission than for low-severity ED visits.

Having at least 1 PCP visit a year explained only a small portion of the Medicaid–commercial difference in ED use, potentially driven by similarly high rates of PCP use among Medicaid and commercial patients. However, including information about each patient's specific PCP (through PCP fixed effects) increased the portion of the explained difference, particularly for low-severity ED visits. There could be several possible explanations for this positive correlation between a patient's PCP and low-severity ED visits. If Medicaid patients were seen primarily by busy or under-resourced PCPs who could not cater to all of their needs, these patients might be more likely to visit the ED for primary care treatable conditions. The availability of PCPs may vary broadly, with some PCPs offering extended evening and weekend services and same-day appointments and others restricting their scheduling and availability. 29 , 30 PCPs also may differ in their comprehensiveness of care. 30 , 31 Overall, this study's results confirm an important role for Medicaid patients' PCPs in reducing low-severity ED visits. By contrast, controlling for each patient's PCP only slightly increased the explained portion of the difference in high-severity ED visits and barely changed the corresponding portion for ED visits resulting in an inpatient admission. This suggests that the more discretionary the nature of the ED visit, the greater was the relevance of the patient's PCP in driving higher ED use among Medicaid enrollees.

The unexplained difference in ED use between Medicaid and commercial patients could be attributed to multiple factors. Medicaid patients might visit the ED more frequently because they face minimal or no co-payments, while commercial patients face higher co-payments. However, the cost sharing differential between Medicaid and commercial patients exists across most of the health services explored, including mental health visits, inpatient hospitalization, high-severity ED visits, and ED visits resulting in an inpatient admission, where Medicaid–commercial differences were relatively small. Thus, it is not clear if the cost sharing differential accounts for the large difference in ED use between Medicaid and commercial patients.

Alternatively, Medicaid patients may have been acculturated to use the ED frequently because the ED can address patients' health care needs all at once and it requires no prior appointments. 30 , 32 Other unobserved factors might include patterns in how providers treat Medicaid patients. Although providers could relatively easily refuse or postpone treatments of Medicaid patients in a mental health, inpatient, and primary care setting, ED providers are mandated to provide care to all patients who present in the ED regardless of their insurance status under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act. Additionally, the patient's social determinants of health such as housing instability, food insecurity, or lack of transportation availability could be important factors contributing to higher rates of ED use for Medicaid enrollees. 32 This would imply that potential interventions for ED use reduction might need to occur outside of the health system. Finally, policy changes such as the introduction of coordinated care organizations in Oregon's Medicaid program or increased insurance coverage through health insurance exchanges could be another unobserved factor, although the year dummy variables controlled for this trend to some degree.

There are several limitations to this study. First, a large portion of the difference in ED visits could not be explained, particularly low-severity ED visits, with health claim information from the database. This suggests that extra data sources might be needed to fully understand contributing factors to the ED use difference between Medicaid and commercial patients. Given the difficulty of obtaining additional data, however, the quest to accurately understand the factors contributing to high rates of ED use and devise effective policy options is indeed challenging, albeit worthwhile. Also, if unobserved factors were correlated with observable factors in the model, the size of the contribution of observable factors in the current model could be biased. Thus, the relationship between observable factors and ED use should be understood in terms of associations, not causal relationships. PCP fixed effects explained about 8% of the Medicaid–commercial differences in ED use. However, the individual PCP characteristics that may have contributed to the Medicaid–commercial differences in ED use could not be identified. Claims related to substance abuse were excluded, and therefore ED use related to substance abuse was not included in the analysis. However, this might lead to a conservative bias because Medicaid beneficiaries have shown much higher risk for substance abuse related ED visits than commercially insured beneficiaries. 33 Moreover, the data set used covers 2011 to 2013, prior to the Medicaid expansion starting in 2014, and therefore does not reflect newly enrolled Medicaid beneficiaries' ED use. Finally, the data are from Oregon; generalizability to other states could be limited.

Conclusions

Reducing rates of ED use among Medicaid patients continues to be an area of priority for states looking to control Medicaid costs. This study examined the extent to which observable factors at both the individual and community levels can explain differences in ED use. The results indicated that in addition to their higher disease burden, Medicaid patients' PCP choice was a significant factor in explaining higher rates of ED use, highlighting the important role of PCPs in reducing low-severity ED visits. The remaining unexplained difference suggests that ED use remains a fruitful target for policy makers, although success may require additional knowledge about patients' perceptions and behaviors as well as social determinants of health.

Supplementary Material

Author disclosure statement.

Drs. Kim and McConnell, and Mr. Sun declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors received the following financial support: NIH Common Fund Health Economics Program (1R01MH1000001) & Silver Family Foundation.

Call for a Quote 833-567-4268

Emergency Department Visits Show How Divided Americans Are by Health Insurance

By Dan Grunebaum Data Journalist

Dan Grunebaum Data Journalist

Dan Grunebaum is a data journalist and visualization developer for HealthCare.com. Dan has experience with surprise medical bills and seeks to bring clarity to the healthcare conversation.

In this Article

We want to help you make educated healthcare decisions. While this post may have links to lead generation forms, this won’t influence our writing. We adhere to strict editorial standards to provide the most accurate and unbiased information.

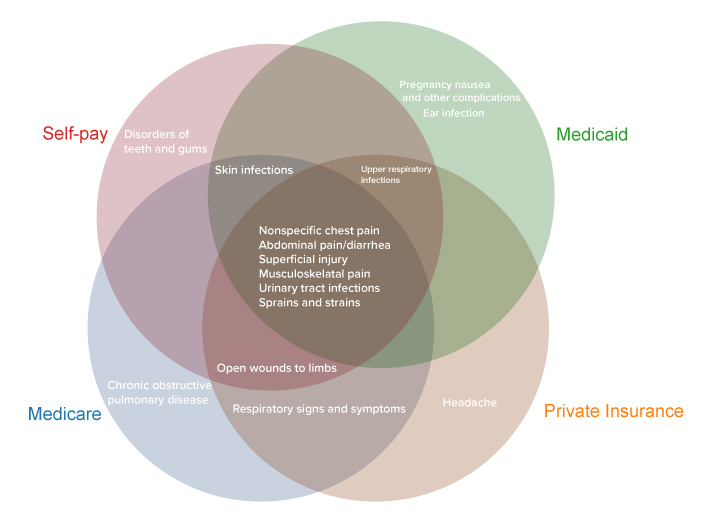

Top Diagnoses by Payer Among Emergency Department Visits (Treat-and-Release)

Key takeaways

- Americans made 143.5 million visits to emergency departments in 2018, 439 visits per 1,000 people

- The most common treat-and-release ED visits were for abdominal pain, respiratory infection, and chest pain

- Among the 15 top treat-and-release diagnoses, the 4 payer types (Medicare, Medicaid, private, self-pay) have in common just 6

- The average cost of an ED visit by payer is: $660 (Medicare), $560 (private insurance), ($460) self-pay, and $420 (Medicaid)

- Americans in the lowest income quartile visit EDs at a rate of 641 per 1000, compared to 281 per 1000 for the highest income quartile

- ED visits by privately insured and self-pay Americans declined over time (2009-2018), while visits by people with Medicare and Medicaid grew

Americans with different kinds of health insurance visit emergency departments for different reasons. A HealthCare.com analysis of federal data shows that, among the 15 top conditions behind treat-and-release visits, the four main payer types (private insurance, self-pay, Medicare, Medicaid) have in common just six conditions.

The above figure shows the six conditions are:

- Nonspecific chest pain

- Abdominal pain/diarrhea

- Superficial injury

- Musculoskeletal pain

- Urinary tract infections

- Sprains and strains

At the same time, five conditions behind treat-and-release ED visits are among the top 15 for only one payer type.

- Headaches are among the top 15 for people with private insurance

- Teeth and gum disorders are among the top 15 for self-payers

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is among the top 15 for people on Medicare

- Pregnancy nausea and ear infections are among the top 15 for people on Medicaid

For all payers, abdominal pain was either the first (for private insurance and self-pay/no charge) or the second (for Medicare and Medicaid) most common condition.

The different attributes of each payer group account for the differing mix of conditions that bring them to emergency departments. Amy Faith Ho , an emergency medicine physician and nationally-published writer, says each group represents a different population. “For example, with Medicare, if you’re an older patient you’re going to come in more with diagnoses associated with getting older,” she explains. “You’re going to see a lot more strokes and urinary infections, but fewer motorcycle accidents and that sort of thing.”

Medicaid tends to represent younger groups and can be heavily pediatric, Ho says, “So you’ll see a lot of kid viruses, and pregnant mothers with pregnancy-related complaints.”

On the other hand, self-payers are often low-income, and may not have the wherewithal to visit dentists regularly. “Perhaps self-pay patients wait until they are really sick to go to the ER,” Ho says. “It makes sense that dental complaints would rank higher for self-paid emergency care visits.” Self-payers, who are mostly uninsured, may not be getting regular dental care.

Emergency Department Visits Nationwide

In 2018, U.S. hospitals saw 143.5 million emergency department (ED) visits, representing 439 visits per 1,000 population. 14% of ED visits resulted in hospital admission (61 per 1,000 population). The majority of ED visits (86%) resulted in treatment and release.

Among all diagnoses with the highest number of treat-and-release ED visits, the below figure shows the top 10.

Top 10 Treat-and-Release Emergency Department Visits (Millions)

Emergency department visits by cost and income level .

The cost of a trip to the emergency department differs significantly depending on what kind of health insurance a person has.

At $420, Medicaid recipients’ ED visits have the lowest average cost, another government brief shows.

Self-payers are next at $460, followed by people on private insurance at $560 per emergency department visit.

At an average of $660, Medicare recipients’ ED visits are the most pricey.

Low-income people, many of whom are Medicaid recipients, are much more likely to visit emergency departments than high-income people.

Americans in the lowest income quartile visit EDs at a rate of 641 per 1000 people, compared to just 281 per 1000 people for the highest income quartile.

The low cost of Medicaid and self-pay Americans’ ED visits may be linked to the higher likelihood of them visiting EDs for less serious conditions like earaches, pregnancy nausea, and dental issues.

It’s also the case, Ho says, that the cost of ED visits reflects the negotiating power of the payer. Large government programs like Medicare and Medicaid are known for negotiating lower prices with healthcare providers.

In terms of outcomes, research shows that emergency departments are an area where folks who don’t have insurance will be at greater risk for financial strain and for putting off critical care.

“We know that expanding health insurance leads to better health and financial security for families,” Ben Sommers, Deputy Assistant Secretary at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, told HealthCare.com.

“The emergency department is one area where disparities can show up prominently. That’s why the department’s focus has been making sure that we have as good coverage and access as we can, and we’ve seen that in near historic lows in the uninsured rate in the past year, and the record high of people enrolled in Affordable Care Act coverage and Medicaid. If you don’t have coverage you’ll face big bills and risk not getting the care you need.”

In peer countries with single-payer healthcare systems like Canada or Japan, such coverage and cost disparities do not exist, for the simple reason that there is only one payer.

“The emergency department is one area where disparities can show up prominently…If you don’t have coverage, you’ll face big bills and risk not getting the care you need.” Ben Sommers, Deputy Assistant Secretary, Department of Health and Human Services

Use the interactive data visualization below to search emergency department costs for your demographic.

The Cost of Emergency Department Visits

Emergency department visits over time.

Over the last decade for which data is available (2009-2018), emergency department visits by privately insured and uninsured (self-pay) people have declined, while visits by people with Medicare and Medicaid have risen.

This tracks with the overall growth of the Medicare and Medicaid programs during that timeframe.

In particular, the proportion of visits by self-payers dropped between 2013 and 2015, coinciding with the large reduction in the uninsured rate nationally under the Affordable Care Act during that period.

“The Medicaid expansion has shifted people away from being uninsured to being covered by Medicaid,” Sommers says. “So what you’re seeing is a result of the major changes brought by the Affordable Care Act over time.”

The rise of urgent care and retail clinics in recent years brought hopes for an easing of expensive emergency department visits. But the dividend hasn’t materialized. A Report to Congress says that “thus far, these care settings do not appear to have resulted in a reduction in the national rate of ED visits.”

Doctor Ho says that, after spiking during the early part of the covid pandemic, emergency departments are no longer jam-packed. “I don’t think EDs are overwhelmed anymore,” she says. “Nationally, volume is actually down a bit. There are a lot of places in the U.S. that are seeing very little covid, that are back to the usual mix of patients and diagnoses.”

For the foreseeable future, it looks like Americans will continue to utilize emergency departments for medical issues that could be resolved more cheaply by primary care physicians, or at urgent care centers. And the conditions for which they tend to visit EDs, and the cost and volume of their visits, will continue to break down along the lines of the nation’s Balkanized health insurance landscape.

Emergency Department Visits by Payer over Time

- Thanks for your feedback! | Sign up for our HealthCare newsletter, and receive useful Health Care related information.

- Hard To Understand

- Tell us a little bit more

- Enter your email

Share this article

About dan grunebaum, related articles.

A Guide to Medicaid Eligibility for Non-U.S. Citizens

Living in the United States but not a citizen? Are you wondering...

April 4th, 2024

A Guide to Navigating Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance

Understanding Your Job’s Health Insurance Choosing health insurance can be tricky, especially...

Buying Individual Marketplace Health Insurance Plans

Finding the right health insurance might sound tricky, but it’s not as...

April 1st, 2024

We do not sell insurance products, but there may be forms that will connect you with partners of healthcare.com who do sell insurance products. You may submit your information through this form, or call 855-617-1871 to speak directly with licensed enrollers who will provide advice specific to your situation. Read about your data and privacy .

Our mission is to provide information that will help everyday people make better decisions about buying and keeping their health coverage. Our editorial staff is comprised of industry professionals and experts on the ACA, private health insurance markets, and government policy. Learn more about our content .

- Search for: >" />

Are Medicaid patients overusing the ER?

Co-authored by Josie Phillips, policy intern.

Note: This post has been updated to correct the number of ER visits by Medicaid enrollees reported in 2019 and to clarify that the declining trend of ER utilization is unlikely to cause health care costs to increase in the near future. [5/5/21]

As part of a larger pattern of demonizing the social safety net , critics of the Medicaid program frequently claim that patients overuse emergency rooms for non-emergency care and that the state must address this problem to contain Medicaid spending. However, there is little evidence to support this claim. In reality, Oklahoma’s SoonerCare enrollees use the emergency room at rates comparable to the general population, and emergency services represent a small fraction of total SoonerCare expenditures. Legislators concerned about rising health care costs should worry less about the health care practices of individual SoonerCare members and more about how we can most effectively provide health care for all Oklahomans through the SoonerCare program.

SoonerCare patients aren’t overusing the emergency room

ER usage by SoonerCare members is nowhere near as pervasive or as serious a problem as many assume, according to data from the Oklahoma Health Care Authority (OHCA). In fact, ER utilization rates have significantly decreased in recent years. In the fiscal year ending in 2019, nearly three in four Medicaid patients (73 percent) made no emergency room visits at all. Another 22 percent visited the ER once or twice. Only 11,073 individuals, or 1.1 percent of those insured by Medicaid, had six or more ER visits. Even when accepting the premise that some Medicaid patients use the emergency room at a higher rate, it is clear that the hypothetical misusers make up a tiny proportion of all SoonerCare members.

Additionally, although differences in demographic make-up and data sources make direct comparison difficult, ER utilization for Medicaid patients appears to be stable — with annual visits ranging from 0.52 to 0.62 per member since 2007 — and comparable to the overall population. All Oklahomans (regardless of health care coverage) had 492 ER visits per 1,000 people in 2019, and that number was 533 visits per 1,000 Medicaid enrollees . ER usage among SoonerCare members has steadily declined in recent years, making it unlikely that this will cause health care costs to balloon in the near future.

It is also not apparent that ER visits are a major expense in the Medicaid program. In fiscal year 2019, total emergency department costs for SoonerCare members were $139 million , which represented less than 3 percent of the total SoonerCare expenditures of $5.6 billion. (If we also include additional ancillary services, the total cost was $177 million, or 3.2 percent of total expenditures.) If Oklahoma policymakers are looking for ways to decrease health care spending, demonizing a group that accounts for a tiny fraction of total spending would be an ineffective place to start.

Medicaid expansion could temporarily increase ER usage, but managed care won’t solve that problem

Oklahoma’s decision to expand Medicaid this year may change the situation, although not in any meaningful magnitude. ER usage may increase slightly following the implementation of Medicaid expansion but will likely decline over time as individuals receive more preventative care . Any increase in ER visits will likely be small, based on evidence from other states. After Medicaid expansion, Kentucky saw a one percent increase in ER visits, and Maryland did not see any increase at all. Another study of 14 states that expanded Medicaid found an increase of only 2.5 visits per 1,000 people. Either way, any increase will likely be temporary, with ER usage declining after a few months , possibly even to levels lower than the pre-expansion period .

No matter what, it’s unlikely that the state’s push to privatize the Medicaid program will help address ER usage. Research suggests that managed care doesn’t impact ER utilization . Instead of pushing this substantial change to privatized managed care, OHCA could instead adopt practices that increase access to primary care outside of normal work hours, such as increasing funding for community health centers. This would provide a non-emergency room path to care for Oklahomans who work during the day and might otherwise rely on the ER for primary care because they are unable to take leave to see a doctor.

Oklahoma’s approach to health care should be informed by data, not by political talking points

OHCA’s efforts to monitor and prevent inappropriate emergency room usage are important in ensuring responsible use of taxpayer dollars. However, the idea that many Medicaid members make unnecessary trips to the ER seems to reflect myths and anecdotes rather than being based in reality. Instead of shaming the people who are insured by SoonerCare, Oklahoma policymakers should adopt and fund targeted actions that will reduce reliance on the emergency room, such as ensuring a robust and accessible Medicaid expansion and providing pathways to more accessible primary care.

About the Co-Author

Josie Phillips is a policy intern for OK Policy. She graduated from the University of Oklahoma with a double major in Economics and International & Area Studies. She is an alumna of OK Policy’s Summer Policy Institute.

Share This:

About the author.

Emma Morris worked as Oklahoma Policy Institute's Health Care and Fiscal Policy Analyst from April 2021 to January 2024. She had previously worked as an OK Policy intern and as the Health Care Policy Fellow. Previous experience included working as a case manager with justice-involved individuals and volunteering as a mentor for youth in her community. Emma holds dual bachelor’s degrees in Women’s and Gender Studies and Public and Nonprofit Administration from the University of Oklahoma, and is currently working on a Master of Public Administration degree from OU-Tulsa. She is an alumna of OK Policy’s 2019 Summer Policy Institute and The Mine, a social entrepreneurship fellowship.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Budget and Taxes

- Economic Opportunity

- Justice System

- Race and Equity

- Voting and Elections

- Jobs & Fellowships

- Merchandise

- Invite Us to Speak

- Online Budget Guide

- KIDS COUNT Data Center

- Legislative Primer

- CountySTATS

- What’s That? Glossary

- Take Action

- Advocacy Toolkit

- Find Your Legislators

- Open Justice Oklahoma

- Together Oklahoma

- 15th Anniversary Celebration

- 2023 State Budget Update

- Oklahoma Summer Policy Institute

- Press Releases & Statements

- Columns & Op-Eds

- Articles & Research

- In The Know

- Weekly Wonk

Common Questions

Does medicaid cover emergency room visits.

- by Christian Worstell

- January 12, 2024

There may be no other type of health care where insurance coverage is more critical than emergency room visits. After all, you’re less likely to be thinking about costs and coverage in the event of an emergency, when receiving quick care is top of mind.

Fortunately for Medicaid beneficiaries, Medicaid covers emergency room visits.

When does Medicaid pay for ER visits?

Each state has two sets of Medicaid benefits : those that are required by the federal government to be offered (mandatory) and those that the state chooses to offer on its own (optional). Emergency room care is a mandatory benefit that Medicaid covers in every state.

Learn More About Medicare

Join our email series to receive your free Medicare guide and the latest information about Medicare and Medicare Advantage.

By clicking "Sign me up!” you are agreeing to receive emails from MedicareAdvantage.com.

How is emergency room care covered under Medicaid?

Although every state is required to provide Medicaid coverage of emergency room visits, the way this care is covered can vary by state.

- Some states, such as Arizona, do not require Medicaid beneficiaries to pay a copayment upon visiting an emergency room. Other states, such as Georgia, may charge a flat $3 copayment for any emergency room visit.

- Other states, such as Alaska, may charge a 5% coinsurance of the Medicaid reimbursement amount for an emergency room visit. Some states, such as Colorado, may charge $4 for a visit that is determined to be an emergency and $6 for visits deemed to not be an emergency.

- States may also impose certain restrictions on Medicaid emergency room coverage, such as needing prior authorization or a “medically necessary” designation by a doctor.

We recommend that you contact your state Medicaid program for more information about how your emergency room visit may be covered by your state’s Medicaid program.

Compare plans today.

Speak with a licensed insurance agent

1-800-557-6059 | TTY 711, 24/7

Will Medicaid pay for an ER visit out of state?

Emergencies can happen anytime, including when you’re visiting another state .

There are four instances in which a state Medicaid program must provide coverage and care to a beneficiary who lives in another state.

- During medical emergencies

- When the beneficiary’s health would be endangered by having to travel back to their home state

- If the necessary services and resources are more readily available than they are in the beneficiary’s home state

- When it’s commonplace for beneficiaries in one locale to receive medical services in a bordering state

If one of the above criteria applies to your emergency room visit, you will likely receive Medicaid coverage for the care. It should be noted that states have some broad flexibility in how they determine out-of-state payment rates.

Is urgent care covered by Medicaid?

Whether or not Medicaid will cover care received at an urgent care clinic or other walk-in clinic will depend on the type of care you receive and the state you live in.

For example, clinic services are an optional benefit that is left up to each state to cover at their own discretion, but physician services are a required benefit in every state. Your coverage may depend on whether the care you receive is considered a clinic service or a physician service.

Rural health clinic services and federally qualified health center services are both required benefits in every state, so if your urgent care visit falls under either category, it would be covered by Medicaid.

Most urgent care facilities in the U.S. accept Medicaid, but it’s always a good idea to ask prior to receiving any billable services.

Medicaid-Medicare plans that cover emergency room care

Some Medicaid beneficiaries are also eligible for Medicare. Some “dual-eligible” beneficiaries may be able to enroll in a certain type of Medicare Advantage plan called a Dual-eligible Special Needs Plan , or D-SNP.

These plans are designed specifically for those who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, and they can include benefits that are not traditionally offered by either Medicare or Medicaid.

If you are eligible for Medicare, speak to a licensed insurance agent to find out if Dual-eligible Special Needs Plans are available in your area and what they cover.

About the author

Christian Worstell is a senior Medicare and health insurance writer with MedicareAdvantage.com. He is also a licensed health insurance agent. Christian is well-known in the insurance industry for the thousands of educational articles he’s written, helping Americans better understand their health insurance and Medicare coverage.

Christian’s work as a Medicare expert has appeared in several top-tier and trade news outlets including Forbes, MarketWatch, WebMD and Yahoo! Finance.

Christian has written hundreds of articles for MedicareAvantage.com that teach Medicare beneficiaries the best practices for navigating Medicare. His articles are read by thousands of older Americans each month. By better understanding their health care coverage, readers may hopefully learn how to limit their out-of-pocket Medicare spending and access quality medical care.

Christian’s passion for his role stems from his desire to make a difference in the senior community. He strongly believes that the more beneficiaries know about their Medicare coverage, the better their overall health and wellness is as a result.

A current resident of Raleigh, Christian is a graduate of Shippensburg University with a bachelor’s degree in journalism.

If you’re a member of the media looking to connect with Christian, please don’t hesitate to email our public relations team at [email protected] .

Related articles

Original Medicare (Parts A and B) doesn’t cover routine dental or vision care. 2024 Medicare Advantage (Part C) plans can cover benefits Original Medicare doesn’t cover, but dental and/or hearing benefits may not be available where you live. Learn more and find out how to compare the plans and benefits available in your area. Read more

When you travel or move to another state, does your Medicare insurance go with you? Find out how Medicare works in other areas of the country and how to maintain the coverage you need. Read more

If you are not automatically enrolled in Medicare, you’ll need to have these documents and information on hand when you apply for Medicare benefits. Learn more about what you need to have ready when you apply. Read more

If your Medicare card is lost, stolen or damaged, you can get a replacement card from Social Security and the Railroad Retirement Board, or by calling Medicare or logging into your My Social Security online account. Read more

Things can get confusing when someone is eligible for both Medicare and employer-sponsored health insurance. We’re here to clear it up and help you understand what you should know concerning Medicare and employer coverage. Read more

Medicare can be complex and confusing. This guide covers the 2024 Medicare basics, including all the info about cost, coverage, enrollment and more. Read more

In some cases, you may be able to qualify for Medicare at age 62. Learn more about Medicare eligibility before age 65 and what it means for you. Read more

Discover how to perform everyday tasks using MyMedicare.gov, the official Medicare online user portal, including opening an account, logging in and using the Blue Button. Read more

Join our email series to receive your Medicare guide and the latest information about Medicare.

Please enter your information to get your free quote.

Thanks for signing up for our emails!

Your Medicare guide will arrive in your email inbox shortly. You can also look forward to informative email updates about Medicare and Medicare Advantage.

If you'd like to speak with an agent right away, we're standing by for that as well. Give us a call!

Enter ZIP code

You're on your way to finding a Medicare Supplement plan!

Compare your Medigap plan options by visiting MedicareSupplement.com

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

Proportion of ED visits by insurance type is reported for 2005 and 2016. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

a Statistically significant change in the trend of ED visits for all years between 2005 and 2016 ( P < .05).

eTable. Detailed statistical appendix regarding visit count, rates, standard error, and weighting

- Transforming the Rural Health Care Paradigm JAMA Health Forum Insights September 2, 2020 Margaret B. Greenwood-Ericksen, MD, MSc; Shawn D’Andrea, MD, MPH; Scott Findley, MD

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Greenwood-Ericksen MB , Kocher K. Trends in Emergency Department Use by Rural and Urban Populations in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e191919. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1919

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Trends in Emergency Department Use by Rural and Urban Populations in the United States

- 1 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

- 2 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

- 3 Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

- Insights Transforming the Rural Health Care Paradigm Margaret B. Greenwood-Ericksen, MD, MSc; Shawn D’Andrea, MD, MPH; Scott Findley, MD JAMA Health Forum

Question How do payer status and patient demographic characteristics differ between urban and rural emergency department (ED) visits?

Findings In this cross-sectional study of National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data, rural ED visit rates increased by more than 50%, from 36.5 to 64.5 per 100 persons, outpacing urban ED visit rates, which increased from 40.2 to 42.8 visits per 100 persons. Rural ED use increased for those aged 18 to 64 years, non-Hispanic white patients, Medicaid beneficiaries, and patients without insurance, with a larger proportion of rural EDs categorized as safety-net EDs.

Meaning Rural EDs experienced greater growth in ED use simultaneous with increased pressure as safety-net hospitals.

Importance Patterns in emergency department (ED) use by rural populations may be an important indicator of the health care needs of individuals in the rural United States and may critically affect rural hospital finances.

Objective To describe urban and rural differences in ED use over a 12-year period by demographic characteristics, payers, and characteristics of care, including trends in ambulatory care–sensitive conditions and ED safety-net status.

Design, Setting, and Participants This cross-sectional study of ED visit data from the nationally representative National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey examined ED visit rates from January 2005 to December 2016. Visits were divided by urban and rural classification and stratified by age, sex, race/ethnicity, and payer. Emergency departments were categorized as urban or rural in accordance with the US Office of Management and Budget classification. Codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision ( ICD-9 ), were used to extract visits related to ambulatory care–sensitive conditions. Safety-net status was determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition. Visit rates were calculated using annual US Census Bureau estimates. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey estimates were generated using provided survey weights and served as the numerator, yielding an annual, population-adjusted rate. Data were analyzed from June 2017 to November 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures Emergency department visit rates for 2005 and 2016 with 95% confidence intervals, accompanying rate differences (RDs) comparing the 2 years, and annual rate change (RC) with accompanying trend tests using weighted linear regression models.

Results During the period examined, rural ED visit estimates increased from 16.7 million to 28.4 million, and urban visits increased from 98.6 million to 117.2 million. Rural ED visits increased for non-Hispanic white patients (13.5 million to 22.5 million), Medicaid beneficiaries (4.4 million to 9.7 million), those aged 18 to 64 years (9.6 million to 16.7 million), and patients without insurance (2.7 million to 3.4 million). Rural ED visit rates increased by more than 50%, from 36.5 to 64.5 visits per 100 persons (RD, 28.9; RC, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.3), outpacing urban ED visit rates, which increased from 40.2 to 42.8 visits per 100 persons (RD, 2.6; RC, 0.2; 95% CI, −0.1 to 0.6). By 2016, nearly one-fifth of all ED visits occurred in the rural setting. From 2005 to 2016, rural ED utilization rates increased for non-Hispanic white patients (RD, 26.1; RC, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.4 to 2.8), Medicaid beneficiaries (RD, 56.4; RC, 4.1; 95% CI, 2.1 to 6.1), those aged 18 to 44 years (46.9 to 81.6 visits per 100 persons; RD, 34.7; RC, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.1 to 3.5) as well as those aged 45 to 64 years (27.5 to 53.9 visits per 100 persons; RD, 26.5; RC, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.7 to 2.5), and patients without insurance (44.0 to 66.6 visits per 100 persons per year; RD, 22.6; RC, 2.7; 95% CI, 0.2 to 5.2), with a larger proportion of rural EDs categorized as safety-net status.

Conclusions and Relevance Rural EDs are experiencing important changes in utilization rates, increasingly serving a larger proportion of traditionally disadvantaged groups and with greater pressure as safety-net hospitals.

Recent reports suggest troubling declines in the health of individuals who live in the rural United States, with increases in mortality, 1 greater rates of chronic disease and high-risk health behaviors, 2 and widening differences between rural and urban life expectancy. 3 , 4 Rural areas are further constrained by physician shortages 5 and financially stressed hospitals with operating margins often too narrow to invest in upgrades to optimize care delivery. 6 As a result of these challenges, rural populations may engage with the health care system differently than their urban counterparts. Understanding the health care use of individuals in rural areas may yield insights into addressing these growing health disparities.

Emergency department (ED) use patterns provide a lens into the status of health care delivery in the communities they serve. Emergency departments play a unique and evolving role in the health care system as a site for the unplanned acute care needs of their communities 7 and as the chief location for admission to the hospital. 8 Emergency department visits may reflect progression or exacerbations of poorly controlled chronic diseases or potentially signal barriers in access to usual sources of care, such as primary or specialty outpatient settings. However, traditional office-based care settings require significant resource investment and a robust physician pool, which may be lacking in rural communities. 9 These factors raise the possibility that rural EDs are increasingly serving as a source of care for rural patients in ways that are distinct from their urban counterparts.

To evaluate this hypothesis, we examined changing trends in rural ED visits and assessed for associated drivers. These included patient demographic characteristics and payer status, visit types, and proportion of visits for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions, which can serve as a marker for outpatient care availability. Additionally, we examined the proportion of EDs that met the safety-net classification, as this designation can contribute to the eroding financial solvency of rural hospitals. Our analysis aims to describe use in rural EDs, which, to our knowledge, has never been done previously and has important implications for rural health care delivery.

To determine the yearly number of ED visits and associated confidence intervals, we analyzed data with provided survey weights from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS), an annual, national probability sample survey on use and provision of services in hospital-based EDs, from January 2005 to December 2016. We included all visits to hospital-based EDs. We excluded data from 2012, as the urban/rural classification variable was not publicly available. Emergency departments were categorized as urban or rural in accordance with the US Office of Management and Budget classification from the 2010 census for all years. 10 Because the definition of urban and rural settings can change over time, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis and applied the Office of Management and Budget classification criteria from 2000 and found similar rates.

To determine the reference population on which to generate rates, we used the US Census Bureau estimates of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population, excluding patients in long-term care and incarcerated individuals. These estimates were further divided into urban and rural populations in accordance with the Office of Management and Budget 2010 classifications, then stratified by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. As a result, the Office of Management and Budget definitions for urban and rural were used for NHAMCS data and US Census Bureau data. Therefore, the NHAMCS estimate, generated using provided survey weights, served as the numerator and the US Census estimate, generated by the US Census Bureau, served as the denominator, yielding an annual, population-adjusted rate. This approach is used by NHAMCS in their yearly reports, as detailed in the microdata files, 11 and was confirmed by personal communication with NHAMCS/National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey statisticians (Don Cherry, oral communication, June 2017).

Finally, we calculated rate differences (RDs) by subtracting the 2005 rate from the 2016 rate as an absolute measure of change. We then calculated the annual rate change (RC) by regressing each year’s rate over time, weighted by the inverse of the variance.

Our analysis was conducted between June 2017 and November 2018. This study was exempted from review by the University of Michigan’s institutional review board, as it uses a publicly available data set that contains no patient identifiers, and informed consent was waived. This study is reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guideline. 12

Visit rates are reported by age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status, triage category, and disposition category (ie, hospital admission or transfer). Ambulatory care–sensitive conditions, a set of diagnoses reflecting the quality and availability of outpatient services, mirror the established definitions of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality definitions of prevention quality indicators by validated codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision ( ICD-9 ). 13 The conditions included bacterial pneumonia, hypertension, perforated appendix, congestive heart failure, diabetes (uncontrolled or complications), angina, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, urinary tract infection, and dehydration. Safety-net status was determined by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria, which are based on the proportion of patients without insurance and Medicaid populations served. 14

Annual ED visit rates were calculated using the US Census Bureau estimates of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population, which were divided into urban and rural populations in accordance with the Office of Management and Budget 2010 classifications and then further stratified by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. For the purpose of exploring racial/ethnic disparities, we categorized patients as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or Hispanic using guidance from the NHAMCS. 15 The relative standard errors for each categorization for rural and urban are 30% or less, indicating reliable estimates. Annual estimates of persons by insurance type are based on the American Community Survey, starting in 2008 16 ; in prior years, insurance status was collected by the Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement 17 without county-level identifiers, which prevents identification of urban and rural populations.

Visit rates are reported with 95% CIs based on standard errors provided by the NHAMCS. We report visit rates for 2005 and 2016 by age, sex, race/ethnicity, payer type, and ambulatory care–sensitive conditions. Additionally, to understand trends over time, we calculated the RD across this 12-year period, an approach previously established in the literature, 18 along with the annual RC. Rate change was generated by performing weighted linear regression tests of trend to account for the sampling scheme used by the NHAMCS. Weights were the inverse of the variance estimates calculated from the standard errors as described in previous literature. 19

We additionally reported change in acuity level and disposition category, also with accompanying RD and RC. For 2005 to 2008, the NHAMCS triage category was rated on a 5-point scale, based on the immediacy with which the patient should be seen: (1) immediate, (2) 1 to 14 minutes, (3) 15 to 60 minutes, (4) 1 to 2 hours, and (5) 2 to 24 hours. In 2009, NHAMCS renamed the 5 categories (1) immediate, (2) emergent, (3) urgent, (4) semiurgent, and (5) nonurgent, which we coded as synonymous with the earlier categories.

The number of safety-net EDs was determined by dividing the weighted estimate of urban and rural EDs that met the criteria for safety-net hospitals by the number of urban and rural EDs designated as a service line in the Annual Survey of Hospitals between 2005 and 2016. 20 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines a safety-net ED as meeting 1 or more of the following criteria: (1) having more than 30% of ED visits with Medicaid as the expected source of payment, (2) having more than 30% of visits with self-pay or no charge as the expected source of payment (considered without insurance), or (3) having a combined Medicaid and uninsured pool greater than 40% of visits. 21 All analyses were performed in Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp) accounting for the complex survey design. Level of significance was set at P = .05, and tests were 2-tailed.

From 2005 to 2016, estimated rural ED visits increased from 16.7 million to 28.4 million and estimated urban visits from 98.6 million to 117.2 million ( Table 1 and Table 2 ), with rural increases in non-Hispanic white patients (13.5 million to 22.5 million), Medicaid beneficiaries (4.4 million to 9.7 million), those aged 18 to 64 years (9.6 million to 16.7 million), and patients without insurance (2.7 million to 3.4 million). Rural ED visit rates increased by more than 50%, from 36.5 to 64.5 per 100 persons (RD, 28.9; RC, 2.2; 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.3) between 2005 and 2016 ( Figure 1 and Table 1 ). This increase outpaced urban ED visit rates, which were generally flat, increasing from 40.2 to 42.8 visits per 100 persons (RD, 2.6; RC 0.2; 95% CI, −0.1 to 0.6) ( Figure 1 and Table 2 ). Detailed information on visit counts, rates, and weighting can be found in the eTable in the Supplement .

Across urban and rural EDs during the study, each age group demonstrated increase in use, with a more rapid change in rural visits. For rural EDs, 2 groups experienced statistically significant increases: those aged 18 to 44 years (46.9 to 81.6 visits per 100 persons; RD, 34.7; RC, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.1-3.5) and aged 45 to 64 years (27.5 to 53.9 visits per 100 persons; RD, 26.5; RC, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.7-2.5) ( Table 1 ). In contrast, urban EDs experienced increases in the same age groups but at a slower rate. For those aged 18 to 44 years, visits increased from 41.3 to 45.7 visits per 100 persons (RD, 4.4; RC, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.1-0.9); for those aged 45 to 65 years, visits increased from 29.4 to 39.5 visits per 100 persons (RD, 10.1; RC, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.4-1.0) ( Table 2 ).