Nursing Home Visit

Description

A nursing home visit is a family- nurse contact which allows the health worker to assess the home and family situations in order to provide the necessary nursing care and health related activities. In performing home visits, it is essential to prepare a plan of visit to meet the needs of the client and achieve the best results of desired outcomes.

- To give care to the sick, to a postpartum mother and her newborn with the view teach a responsible family member to give the subsequent care.

- To assess the living condition of the patient and his family and their health practices in order to provide the appropriate health teaching.

- To give health teachings regarding the prevention and control of diseases.

- To establish close relationship between the health agencies and the public for the promotion of health.

- To make use of the inter-referral system and to promote the utilization of community services

The following principles are involved when performing a home visit:

- A home visit must have a purpose or objective.

- Planning for a home visit should make use of all available information about the patient and his family through family records.

- In planning for a home visit, we should consider and give priority to the essential needs if the individual and his family.

- Planning and delivery of care should involve the individual and family.

- The plan should be flexible.

The following guidelines are to be considered regarding the frequency of home visits:

- The physical needs psychological needs and educational needs of the individual and family.

- The acceptance of the family for the services to be rendered, their interest and the willingness to cooperate.

- The policy of a specific agency and the emphasis given towards their health programs.

- Take into account other health agencies and the number of health personnel already involved in the care of a specific family.

- Careful evaluation of past services given to the family and how the family avails of the nursing services.

- The ability of the patient and his family to recognize their own needs, their knowledge of available resources and their ability to make use of their resources for their benefits.

- Greet the patient and introduce yourself.

- State the purpose of the visit

- Observe the patient and determine the health needs.

- Put the bag in a convenient place and then proceed to perform the bag technique .

- Perform the nursing care needed and give health teachings.

- Record all important date, observation and care rendered.

- Make appointment for a return visit.

- Bag Technique

- Primary Health Care in the Philippines

2 thoughts on “Nursing Home Visit”

Thanks alots for the impressive lessons learnt from the principal of community health care and nursing home

Home visit nursing

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Nursing Home Visit – Tips & What To Expect

If you are preparing for your first nursing home visit, read this guide. This is packed with helpful tips so you can be prepared.

Reasons Nurses Do Home Visits

There are lots of reasons that a nurse might visit someone’s home. Before I share some of my tips, it’s important to understand the purpose of the visit. Each type of home visit will have different goals and outcomes, so you’ll do different things when you arrive.

These are the main reasons that nurses might do home visits:

- Care for a sick patient as a home-care nurse

- Teach care techniques to a postpartum family

- Assess the living condition of a patient and/or their family members for upcoming care

- Teach people about prevention and control of diseases from within their homes

- To promote the utilization of community services

7. Make Another Appointment

Your chances of doing a home visit as a nurse will depend on where you work. Typically, community outreach organizations and home health care agencies will do the most frequent home visits.

How To Decide Whether To Do A Home Visit

If you are a new nurse, you probably won’t be the one making the decision about whether to visit a patient’s home, but it is still good to know how the decision is made.

Typically, these are the main guidelines that health care providers use to decide whether nurses should visit a patient in their home:

- The needs of the patient and their family – including physical, psychological, and educational

- Patient and family’s acceptance and willingness to cooperate

- Patient and family’s ability to recognize their needs and their ability to use the resources for their benefits

- How many health personnel are already involved in the care of this specific family

- The policy of the agency in regards to the home visits

How To Do A Home Visit

When it comes time to do your first home visit, just follow these steps in order. This will help you have a pleasant experience and make sure you don’t forget something important.

1. Greet The Patient

Arrive with a smile and introduce yourself. Remember to state where you are coming from and your role in the agency. Make sure you ask them their name and what they prefer to be called (if they have a nickname).

2. Tell Them The Purpose Of The Visit

Go into detail about why you are there and what you are hoping to accomplish. This part should be detailed so that they know what to expect.

3. Assess The Patient

Next you will do a quick observation and assessment. This is a silent and mental one so that you know what you will have to do while on your visit.

4. Set Your Bag In A Clean Place

Make sure your bag is sitting on a table that is lined with clean paper. Then, wash your hands with soap and water. Take out all the tools you will need for your visit so they are easy to access. Put on an apron, close the bag, and you are ready for your nursing care treatment.

5. Perform Your Nursing Care

After you are all prepared, you can do the care which you came to do. One of the most important things you will do on these visits is educate the patient and/or their family. Listen to their questions attentively and answer them the best you can. Direct them to any community services if you cannot help them right away.

6. Keep Excellent Records

Write everything down. Record the date, what you observed, and all the care you gave the patient. Also write down everything you told the family for caring for the patient at home.

If necessary, make an appointment to return and give more care. This is always needed, but don’t leave until you verified whether they need a follow up.

Nursing Home Visit: Final Thoughts

It might be nerve-wracking to think about visiting a patient or their family at their home. If you are really nervous, you can ask a friend or family member to help you prepare. Do a few practice runs as you introduce yourself and go through the motions of the assessment and care.

Set realistic expectations for yourself. If you need notes to remember what to ask, then take them along. Always ask for help when you need it. These can be very valuable and give the education and support that the patient and/or their family

More Nursing Tips

If you enjoyed these nursing home visit tips, then here are some more tips and advice about life as a nurse.

- How To Get ACLS Certified

- How To Write A Cover Letter

- The Best Accelerated Nursing Programs

About The Author

Brittney wilson, bsn, rn, related posts.

Debunking 5 Myths About Millennial Nurses

Male Nurse Jokes and Memes For All the Murses Out There

The nursing process as an administrative nurse.

Best Medical Dictionaries for Nurses

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Start typing and press enter to search

The role of nursing in hospital-at-home programs

Home and inpatient skills combine to provide hospital-level care at home..

- Hospitals aren’t always the best environment for care, especially among older frail adults at risk for hospital-associated complications.

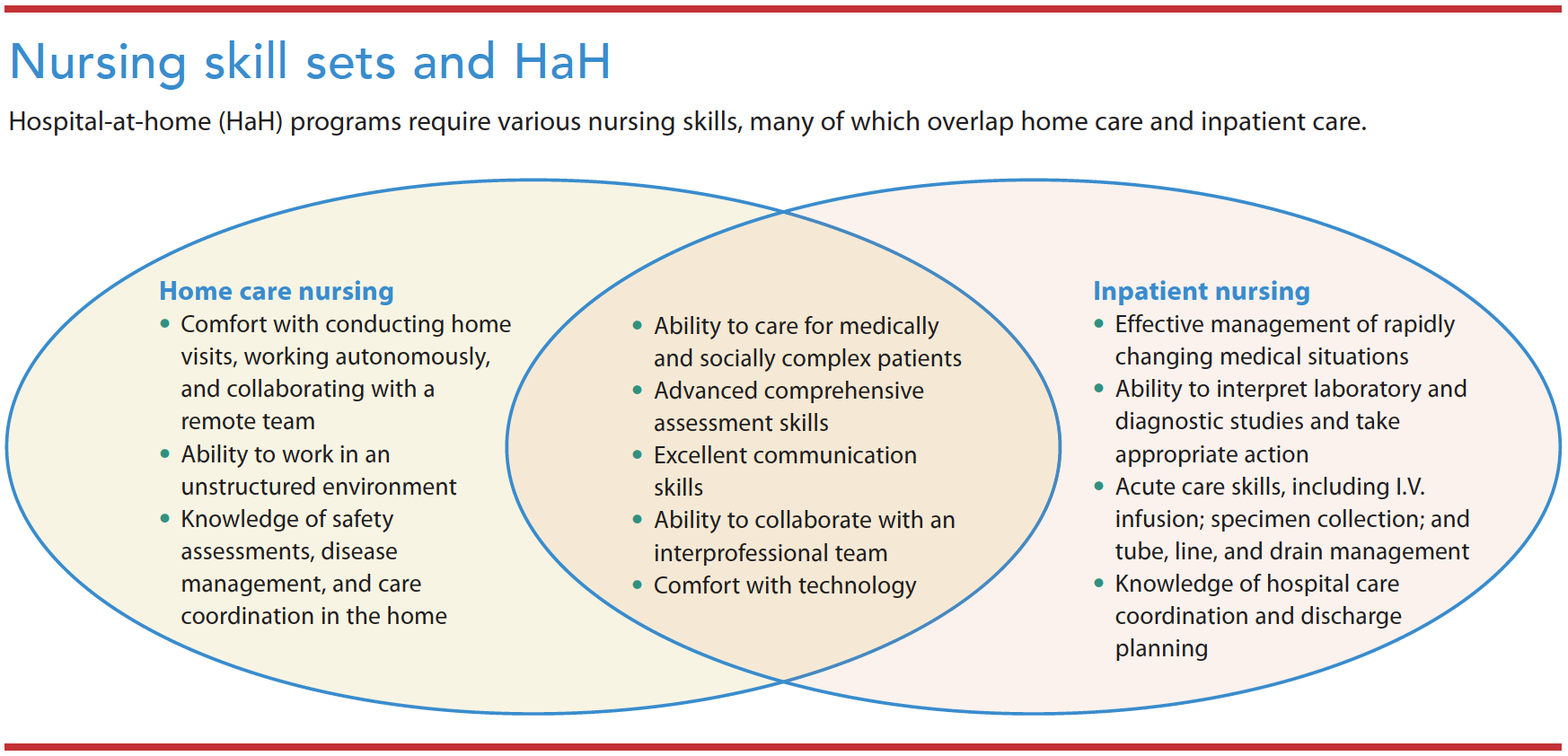

- Acute nursing care in the home draws an skills sets from home health, inpatient, and telehealth medicine.

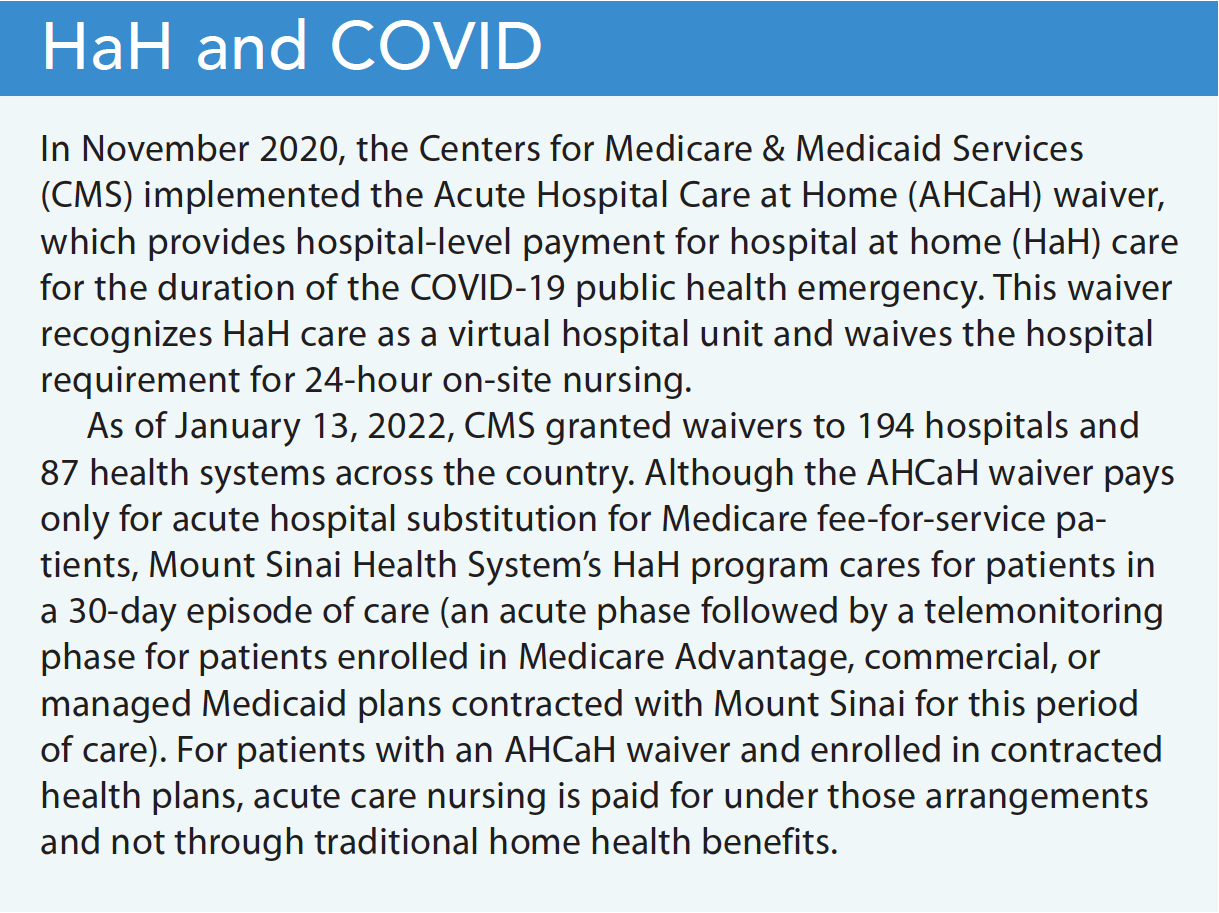

Hospital at home (HaH) provides hospital-level care in a patient’s home in lieu of traditional inpatient care. HaH developed out of recognition that hospitals frequently aren’t ideal care environments, especially for older frail adults susceptible to hospital-associated complications. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, interest in avoiding hospital care has increased. Nursing plays an integral role in HaH care, drawing on skill sets from home health, inpatient, and telehealth medicine.

HaH History

In the 1990s, Bruce Leff, MD, introduced HaH to the United States at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. However, the model stalled due to the multi-payer system and the absence of an accepted payment model. Internationally, HaH has scaled in several countries, including Australia, France, and Spain. A few U.S. health systems have maintained HaH programs since the 1990s, most notably at Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals. Some programs have grown out of home-based primary care (traditional house calls), but are distinctive in patient acuity level (HaH treats acute conditions requiring inpatient care, whereas home-based primary care treats simple acute and chronic conditions).

Evidence suggests that, compared to traditional hospital care, HaH is associated with improved patient safety, reduced mortality, a better patient and family experience, enhanced quality, and reduced cost. Common HaH-qualifying conditions include exacerbations of chronic heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, COVID-19 pneumonia, infections requiring I.V. antibiotics, and post-chemotherapy neutropenia. Eligible patients must live in a safe home environment suitable for HaH care.

In 2014, Mount Sinai Health System, in New York City, received a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation award to implement an HaH program, which so far has cared for more than 1,000 patients. Within the Mount Sinai program, acute care RNs (ACRNs) visit patients twice daily, and a physician or nurse practitioner (NP) sees the patient daily via in-person or telehealth visits. Patients have access to the care team 24 hours 7 days a week, including urgent evaluations by a community paramedic.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, a shift to value-based care drove growing interest in HaH. Hospitals experiencing capacity issues considered HaH programs a solution to increasing traditional hospital capacity. As the initial waves of COVID-19 hit major cities, concerns about hospital capacity led several existing HaH programs to expand and adapt their models. (See HaH and COVID .)

HaH care delivery

The literature describes two main categories of HaH care delivery: substitution HaH and early discharge. Substitution HaH admits patients requiring hospital-level care directly to home, usually from the emergency department (ED). Less commonly, patients enrolled in managed and commercial health plans that contract with the HaH program can be admitted from an ambulatory clinic or directly from home. In early discharge HaH , a patient receiving traditional hospital care and who has a continued need is assessed for eligibility and offered HaH. They’re brought home by medical transport, where they receive the same diagnostic and therapeutic services they would have received in the hospital—blood tests, x-rays, ultrasounds, respiratory treatments, and I.V. medications. HaH also includes many of the same integral staff roles necessary to provide hospital-level care, such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, social work, patient care assistants, phlebotomy, and nursing.

HaH skill set

Whatever the program’s staffing structure, success requires strong clinical, technical, and communication skills. Because clinicians make independent home visits, team members must be flexible, adaptable, and comfortable working autonomously in unfamiliar environments. HaH programs’ application of telehealth modalities, remote patient monitoring, Bluetooth-enabled tools, and Wi-Fi or network-connected platforms requires that staff learn how to use and troubleshoot technology. Telehealth relies on HIPAA-compliant chat modalities for team communication, as well as electronic health records. Staff also may implement point-of-care laboratory diagnostics and mobile tech-enabled solutions to dispense medication and document its administration. In addition to communication with the patient, clinicians also must share information with caregivers who want to learn about the treatment plan, program details, and this new care model. (See Nursing skill sets and HaH .)

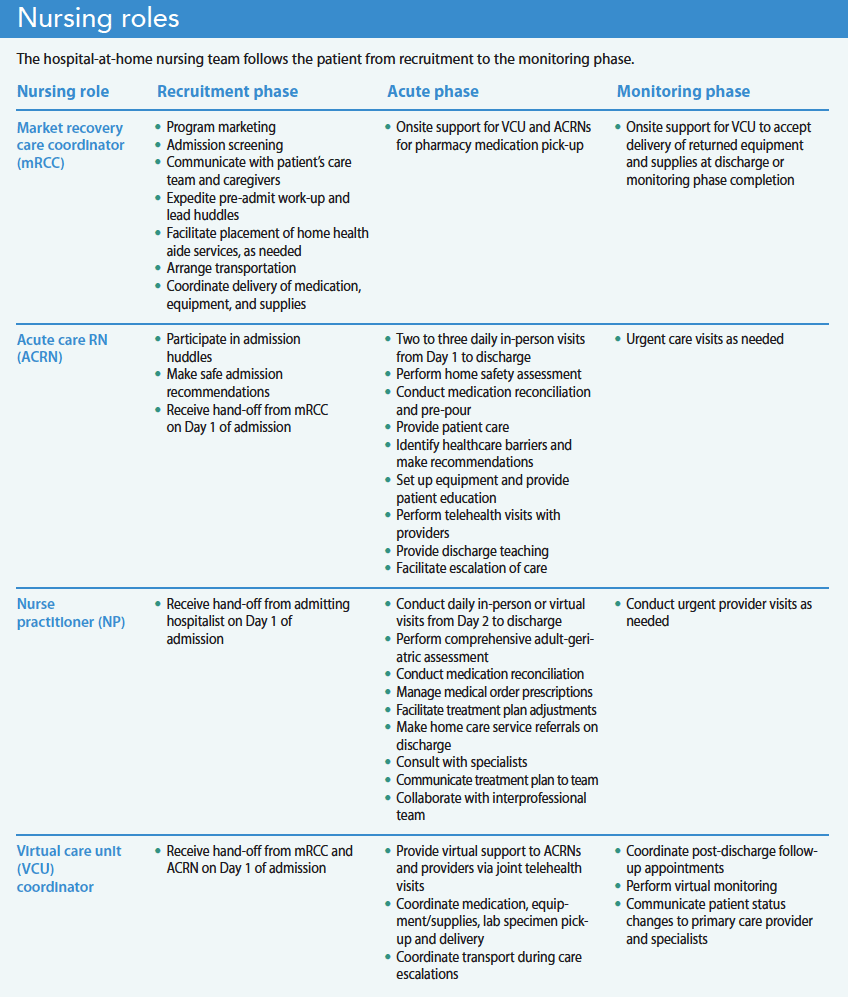

HaH nursing roles

Many HaH nursing teams include market recovery care coordinators (mRCCs), ACRNs, virtual care unit (VCU) coordinators, NPs, and nurse managers with specialized skills and experience in medical-surgical, emergency care, critical care, home care, adult/geriatrics, palliative care, and case management. (Other healthcare organizations may have similar roles with different titles.) The team follows the patient throughout the HaH phases, from recruitment to the acute phase followed by discharge or a monitoring phase. (See Nursing roles. )

Market recovery care coordinators

At Mount Sinai, the mRCC screens and recruits eligible patients and organizes all aspects of the patient’s transfer from the ED or inpatient floor to home. They educate qualified patients, their caregivers, and the ED/inpatient care team about HaH services. Once an interested patient is deemed clinically appropriate, the mRCC collaborates with a care team of hospitalists, nurses, social workers, and case managers to start the HaH admission process. They screen patients at the bedside for home safety concerns using questionnaires and chart reviews, expedite the pre-admission work-up, and lead admission huddles between the ED/inpatient care team and the HaH team.

During the HaH admission process, the mRCC coordinates with hospital social workers and various vendors to facilitate patient care assistant placement, arrange transportation, and coordinate delivery of medication, telehealth equipment, and nursing supplies to the home. Throughout the course of the patient’s HaH stay, the mRCC supports ACRNs and the virtual care team by collecting additional medications and supplies from the hospital pharmacy for delivery to the patient’s home.

Acute care RNs

ACRNs are a group of contracted home health agency nurses specially trained and dedicated to caring for patients in HaH outside of a home health episode of care. At the start of the acute phase, the ACRN arrives at the home within 2 hours of the patient’s arrival to transform it into a hospital room. At this admission visit, the ACRN performs a clinical and safety assessment to ensure patient stability, identifies risk factors that may contribute to a decline in health (such as inadequate caregiver support or food insecurity), and performs a comprehensive medication reconciliation. The ACRN reports clinical changes, home safety concerns requiring escalation back to the traditional hospital, and medication discrepancies to the provider. They also perform patient and family education about the use of telehealth equipment and discharge planning.

The ACRN conducts twice-daily home visits throughout the acute phase to assess the patient’s clinical status, implement nursing orders, and provide ongoing education. Nursing interventions include pre-pouring medication; administrating oral, I.V., and injectable medications; and monitoring patient response to treatment. The ACRN also may manage oxygen, urinary catheters, chest tube drains, wounds, and I.V. access devices.

At follow-up visits, ACRNs arrange telehealth appointments with the patient, provider, and VCU coordinator. During these visits, the ACRN shares assessment findings and electronic stethoscope recordings with the provider to help guide the treatment plan. If a patient shows signs of clinical decompensation, the ACRN collaborates with the provider to schedule a third nursing visit per day, initiate community paramedic visits for advanced diagnostic testing and urgent treatments, or coordinate medical transport or activate 911 to escalate the patient back to the traditional hospital, as clinically appropriate.

During the discharge visit, the ACRN ensures patient readiness and implements discharge orders, including a review of medications, follow-up appointments, and community referrals. For patients eligible for the monitoring phase, ACRNs can conduct urgent visits with patients who can’t seek medical attention at their primary care clinic because of lack of appointment availability.

Virtual care unit coordinators

After acutely ill patients are admitted to HaH, VCU coordinators direct all care management activities. These specialized nursing coordinators offer virtual support to ACRNs and providers during joint telehealth visits, telephone encounters, and electronic communication, such as email and secure chat. Duties during the acute phase include scheduling medication deliveries and following up on orders for oxygen, durable medical equipment, and imaging and diagnostic testing (for example, ECGs and ultrasounds). The VCU coordinator expedites hospital-level consultations from social work and physical therapy, and follows up on patient care assistant placement.

After hours, the VCU coordinator triages urgent patient phone calls and collaborates with on-call physicians to deploy urgent community paramedic visits. In addition, the VCU coordinator, using phone and video visits, periodically follows patients who qualify for the monitoring phase to prevent hospital readmission.

Nurse practitioners

From Day 2 of admission to the HaH program until discharge, the NP manages the patient via in-person and telehealth visits. During the initial home visit, the NP performs a comprehensive adult/geriatric assessment to evaluate the patient’s physical health and identify potential problems that may impact recovery at home, including incontinence issues and cognitive, functional, and sensory impairment. The NP performs a medication reconciliation to evaluate adherence, determine barriers to medication management, and identify inappropriate medications that may lead to confusion, falls, and adverse events. The NP addresses medication discrepancies and updates the HaH treatment plan. The NP also handles caregiver and home safety concerns via orders for urgent durable medical equipment, rehabilitative services, a home health aide, and social work. In addition, the NP orders and reviews pertinent labs and imaging.

If the patient is stable, the NP conducts telehealth visits facilitated by the ACRN and VCU coordinator. For patients with a worsening clinical picture, the NP consults with the attending physician and other specialists, such as infectious disease or pharmacy, to optimize patient care. After patient visits, handoff to the on-call hospitalist occurs during daily clinical huddles where the NP presents pertinent findings along with the assessment and plan.

On discharge, the NP reconciles the outpatient medication list, completes discharge orders, and prescribes medications to the outpatient pharmacy. The NP also orders non-urgent durable medical equipment and home care services for patients with additional needs.

Nurse managers

All nursing teams require a nurse manager. Their responsibilities include recruitment, onboarding, supervision, and staff scheduling. They ensure staff and patient safety by implementing safe home care practices, ensuring adequate supply of personal protective equipment, and assigning patient caseloads according to nurse competency, patient acuity, geography, and visit type.

Responding to patient needs

The nursing team plays a key role in the HaH model and works together to respond to the patient’s acute care needs. The skill sets among coordinators and field clinicians overlap with traditional home health, inpatient nursing roles, and telehealth. As HaH continues to grow, nurses should become familiar with this care model. Hospitals interested in building an HaH program with a robust nursing team should consider participating in the HaH Users Group ( hahusersgroup.org ) as a helpful resource.

Xiomara M. Dorrejo is a nurse practitioner in the Mount Sinai Health System Hospitalization at Home Program in New York, New York. LaToya Sealy is a nurse practitioner in the Mount Sinai Health System Hospitalization at Home Program. Jennifer Shields is an acute care RN in the Mount Sinai Contessa Health/Amedisys Hospitalization at Home Program. Pamela Saenger is a lead provider in the Mount Sinai Health System Hospitalization at Home Program. Katherine A. Ornstein is the director of research at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Linda V. DeCherrie is a professor in the department of geriatric and palliative medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Key words hospital at home, acute hospital care at home, acute care nursing, nursing roles

American Nurse Journal. 2022; 17(12). Doi: 10.51256/ANJ122216

American Nurses Association. Home Health Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice . 2nd ed. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 2014.

Brown CJ. After three decades of study, hospital-associated disability remains a common problem. J Am Geriatr Soc . 2020;68(3):465-6. doi:10.1111/jgs.16349

Caplan GA, Sulaiman NS, Mangin DA, Aimonino Ricauda N, Wilson AD, Barclay L. A meta-analysis of “hospital in the home.” Med J Aust . 2012;197(9):512-9. doi:10.5694/mja12.10480

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Acute hospital at home care at home resources. September 30, 2022. qualitynet.cms.gov/acute-hospital-care-at-home/resources

Federman AD, Soones T, DeCherrie LV, Leff B, Siu AL. Association of a bundled hospital-at-home and 30-day postacute transitional care program with clinical outcomes and patient experiences. JAMA Intern Med . 2018;178(8):1033-40. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2562

Gonçalves-Bradley DC, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Early discharge hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2017;6(6):CD000356. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000356.pub4

Hayashi JL, Leff B. Geriatric Home-Based Medical Care: Principles and Practice . New York, NY: Springer; 2016.

Heller DJ, Ornstein KA, DeCherrie LV, et al. Adapting a hospital-at-home care model to respond to New York City’s COVID-19 crisis. J Am Geriatr Soc . 2020;68(9):1915-6. doi:10.1111/jgs.16725

Hospital at Home Users Group. About the users group. hahusersgroup.org/about-the-users-group/

Leff B, Burton L, Guido S, Greenough WB, Steinwachs D, Burton JR. Home hospital program: A pilot study. J Am Geriatr Soc . 1999;47(6):697-702. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01592.x

Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Hospital at home: Feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med . 2005;143(11):798-808. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-143-11-200512060-00008

Levine DM, Mitchell H, Rosario N, et al. Acute care at home during the COVID-19 pandemic surge in Boston. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3644-6. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-07052-5

Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med . 2020;172(2):77-85. doi:10.7326/M19-0600

Mooney K, Titchener K, Haaland B, et al. Evaluation of oncology hospital at home: Unplanned health care utilization and costs in the Huntsman at home real-world trial. J Clin Oncol . 2021;39(23):2586-93. doi:10.1200/jco.20.03609

Shepperd S, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2016;9(9):CD007491. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007491.pub2

Let Us Know What You Think

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post Comment

NurseLine Newsletter

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Hidden Referrer

*By submitting your e-mail, you are opting in to receiving information from Healthcom Media and Affiliates. The details, including your email address/mobile number, may be used to keep you informed about future products and services.

Test Your Knowledge

Recent posts.

Nearly 100 measles cases reported in the first quarter, CDC says

Infections after surgery are more likely due to bacteria already on your skin than from microbes in the hospital − new research

Honoring our veterans

Many travel nurses opt for temporary assignments because of the autonomy and opportunities − not just the big boost in pay

Health workers fear it’s profits before protection as CDC revisits airborne transmission

Why COVID-19 patients who could most benefit from Paxlovid still aren’t getting it

My old stethoscope

The nurse’s role in advance care planning

Sleep and the glymphatic system

The transformational role of charge nurses in the post-pandemic era

Health Care Workers Push for Their Own Confidential Mental Health Treatment

Do We Simply Not Care About Old People?

Eating disorders are the most lethal mental health conditions – reconnecting with internal body sensations can help reduce self-harm

ChatGPT and aging

What’s the best diet for healthy sleep? A nutritional epidemiologist explains what food choices will help you get more restful z’s

What to Expect at Your First Home Care Visit

When you’re coming home from the hospital, it can be a relief to know that your doctor’s orders include home care. At the same time, you may be unsure about what to expect from your first home care visit or how to prepare for it. With VNS Health, your care will be tailored to your unique needs.

Before Your First Visit

While you’re still in the hospital, a VNS Health representative will work with your doctor to determine the care you will need once you’re home. On the day you go home, your VNS Health representative will help ensure a smooth transition as you are discharged. You’ll have that day to get settled, fill any prescriptions, and rest before your first home care visit. It’s important to understand that your home care nurse will not visit you on your first day back from the hospital.

The morning after you go home, a representative from VNS Health will call you to tell you what time your nurse will visit.

After a hospital visit or injury, you have enough to worry about. We offer expert care so you or a loved one can recover safely in the comfort of home.

At the First Visit

During your first visit, your nurse will explain all the details of your plan of care, including which other VNS Health professionals — such as physical therapists, social workers, registered dietitians, and home health aides — are part of your home care team and how often you’ll see them.

If you received instructions about your care while you were in the hospital, your nurse will review them with you to make sure you understand and are comfortable performing them. Be sure to have your discharge instructions and a list of medications ready to show the nurse. Your nurse will also remind you of your follow-up doctor’s appointments, will answer any questions you or your caregivers have, and will demonstrate any techniques necessary for your care. In addition, your nurse will order any supplies you need, from oxygen to sterile gloves, and teach you and your caregivers how to use any special equipment that’s part of your treatment.

Your nurse will also perform a thorough evaluation of your condition. They will:

- Check your vital signs

- Monitor any wound or incision sites

- Administer any medications

Depending on your needs, your first visit may last up to 3 hours.

During Your Time Receiving Home Care

VNS Health will provide all the services your doctor has ordered. We’ll help you understand what to expect regarding your medical condition and recovery, teach you how to manage and monitor your condition, and support you through your recovery.

The best way to make home care successful is to prepare for it in advance by making a list of responsibilities and chores you’d like the home care professional to take on. This way, you can be sure you will receive the help you need. It’s also smart to map out a schedule for meals, medications, sleep, exercise, and other activities and to make a list of emergency phone numbers for doctors, as well as friends and family members who can help in a pinch.

Whether you require skilled medical care or assistance with personal care, you can be sure that your plan of care will include all the services your doctor prescribes to meet your needs.

Sign up for VNS Health’s newsletter just for caregivers.

Best Qualities of a Home Health Aide for Someone with Dementia

How to Choose a Home Care Agency That Is LGBTQ+ Friendly

What to Know About Recovery from Gender Affirmation Surgery

Choose vns health for your loved one's care..

Effect of Home Visits by Nurses on the Physical and Psychosocial Health of Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Public Health Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, İstanbul Aydın University, İstanbul, Turkey.

- 2 Department of Public Health Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Lokman Hekim University, Ankara, Turkey.

- 3 Department of Public Health Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Selcuk University, Konya, Turkey.

- PMID: 35936539

- PMCID: PMC9288399

- DOI: 10.18502/ijph.v51i4.9234

Background: One of the best ways to maintain and develop physical and psychosocial health is to make regular home visits. This meta-analysis aimed to determine (by subgroups) the effects of interventions based on nurses' home visits on physical and psychological health outcomes of older people.

Methods: This search was carried out using the The CINAHL, Cochrane, MEDLINE, PubMed, Science Direct, Web of Science, and Turkish databases. Experimental and observational studies were included.

Results: The meta-analysis included 26 (with subgroups 50) out of 13110 studies. The minimum and maximum values of the effect size (Hedges g) were g = -0.708 and g = 0.525, respectively. The average effect size was g = 0.084 (SD = 0.21).

Conclusion: Home visit interventions are effective in reducing the frequency of hospitalization in the older adults, and improving physical and psychosocial health. They are negatively effective on falls and have no significant effect on the quality of life.

Keywords: Health; Home visit; Meta-analysis; Older adults; Systematic review.

Copyright © 2022 Ergin et al. Published by Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Publication types

During a home visit, the home health practical nurse (PN) observes an older client attempting to ambulate to the bathroom and notes that the client is unsteady and holds on to furniture while refusing any assistance. Which action should the PN implement?

Determine home navigational safety hazards.

Encourage the client to obtain a medical alert device.

Recommend that the client obtain a walker.

Maintain the client's privacy while in the bathroom.

The correct answer is Choice A:

"Determine home navigational safety hazards.”. Choice A rationale:

The PN should first assess the client's home for safety hazards that may be contributing to the client's unsteadiness and increased fall risk. Identifying and addressing these hazards can help create a safer environment for the client and potentially prevent accidents.

Choice B rationale:

Encouraging the client to obtain a medical alert device is not the immediate priority in this situation. Addressing the client's safety and identifying potential hazards should be the first step before considering additional measures like medical alert devices.

Choice C rationale:

Recommending that the client obtain a walker is premature without first assessing the home

environment and determining if there are any correctable safety issues. The PN should prioritize safety assessment before recommending any assistive devices.

Choice D rationale:

While maintaining the client's privacy is important, it is not the most urgent action in this scenario. The priority is to assess the client's safety and identify potential hazards in the home. Privacy concerns can be addressed afterward.

Nursing Test Bank

Naxlex comprehensive predictor exams.

Related Questions

An unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) is completing an orientation assignment and is caring for a client who needs assistance with bathing. What is the best way for the practical nurse (PN) to evaluate this UAP's performance?

Correct answer is d, explanation.

Observe the UAP's technique and communication skills during the bath.

The PN should directly observe the UAP's performance and provide feedback and guidance as needed. This can help ensure that the UAP follows the standards of care and respects the client's dignity and preferences.

The other options are not correct because:

- Asking another UAP to help the orientee may not be appropriate or necessary, as it may interfere with the orientation process and create confusion or conflict.

- Verifying with the client that the bath was complete and thorough may not be sufficient or reliable, as the client may not be able to assess the quality of care or may not want to complain.

- Inspecting the client's skin near the end of the bathing procedure may not be timely or comprehensive, as it may miss some aspects of care or some problems that occurred during the bath.

While ambulating in the hallway following an appendectomy yesterday, a client complains of chest tightness and shortness of breath. Which action should the practical nurse (PN) implement first?

Correct answer is c.

Choice A rationale:

The PN should prioritize addressing the client's symptoms of chest tightness and shortness of breath immediately. Having the client sit down in the hall might help to some extent, but it does not address the potential underlying issue of a cardiac event, which requires prompt intervention.

While assisting the client back to the room is important for providing a safe environment, it should not be the first action taken in this situation. The client's symptoms may be indicative of a cardiac event, and delaying treatment could have serious consequences.

Administering sublingual nitroglycerin is the most appropriate first action. Chest tightness and shortness of breath could be indicative of angina or myocardial infarction (heart attack). Nitroglycerin is commonly used to treat angina by dilating blood vessels, reducing the workload on the heart, and improving blood flow to the heart muscle. It is a time-sensitive intervention that can help alleviate symptoms and prevent further complications.

Obtaining a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is important to assess the client's cardiac status, but it should not be the first action in this acute situation. The PN should address the client's symptoms and provide immediate relief before proceeding to gather more data through an ECG.

A woman who delivered a normal newborn 24 hours ago reports, "I seem to be urinating every hour or so. Is that OK?”. Which action should the practical nurse (PN) implement?

The practical nurse (pn) learns that a client who is receiving chemotherapy has developed stomatitis. which information should the pn obtain from the client during a focused assessment, a client with obstructive sleep apnea is preparing for sleep. which action should the practical nurse (pn) implement, while changing the dressing of a client who is immobile, the practical nurse (pn) observes a red and swollen wound with a moderate amount of yellow and green drainage and a foul odor. before reporting this finding to the healthcare provider, the pn should evaluate which of the client's laboratory values, the practical nurse (pn) believes that a prescription for a child is incorrect because the dosage prescribed is the usual adult dosage. which action should the pn take, when performing a focused gastrointestinal system assessment, the practical nurse (pn) asks a male client when his last bowel movement occurred. the client answers, "three days ago.”. which action should the pn implement first, a client is being treated for chronic kidney disease (ckd). on examination, the client has an elevated blood pressure (bp) and is exhibiting changes in mental status. which intervention in the plan of care should the practical nurse (pn) implement, the practical nurse (pn) reviews the history of an older adult who is newly admitted to a long-term care facility. which factor in the resident's history should the pn consider the most likely to increase the client's risk for falls.

Whether you are a student looking to ace your exams or a practicing nurse seeking to enhance your expertise , our nursing education contents will empower you with the confidence and competence to make a difference in the lives of patients and become a respected leader in the healthcare field.

Visit Naxlex , invest in your future and unlock endless possibilities with our unparalleled nursing education contents today

Report Wrong Answer on the Current Question

Do you disagree with the answer? If yes, what is your expected answer? Explain.

Kindly be descriptive with the issue you are facing.

Submitting...

- Open access

- Published: 13 April 2024

Changes in long-term care insurance revenue among service providers during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Tomoko Ito 1 , 2 ,

- Xueying Jin 2 , 3 ,

- Makiko Tomita 2 , 4 ,

- Shu Kobayashi 4 &

- Nanako Tamiya 1 , 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 464 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

174 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted peoples’ health-related behaviors, especially those of older adults, who have restricted their activities in order to avoid contact with others. Moreover, the pandemic has caused concerns in long-term care insurance (LTCI) providers regarding management and financial issues. This study aimed to examine the changes in revenues among LTCI service providers in Japan during the pandemic and analyze its impact on different types of services.

In this study, we used anonymized data from “Kaipoke,” a management support platform for older adult care operators provided by SMS Co., Ltd. Kaipoke provides management support services to more than 27,400 care service offices nationwide and has been introduced in many home-care support offices. The data used in this study were extracted from care plans created by care managers on the Kaipoke platform. To examine the impact of the pandemic, an interrupted time-series analysis was conducted in which the date of the beginning of the pandemic was set as the prior independent variable.

The participating providers were care management providers ( n = 5,767), home-visit care providers ( n = 3,506), home-visit nursing providers ( n = 971), and adult day care providers ( n = 4,650). The results revealed that LTCI revenues decreased significantly for care management providers, home-visit nursing providers, and adult day care providers after the COVID-19 pandemic began. The largest decrease was an average base of USD − 1668.8 in adult day care.

The decrease in revenue among adult day care providers was particularly concerning in terms of the sustainability of their business. This decrease in revenue may have made it difficult to retain personnel, and staff may have needed to be laid off as a result. Although this study has limitations, it may provide useful suggestions for countermeasures in such scenarios, in addition to support conducted measures.

Peer Review reports

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed many peoples’ health-related behaviors. In particular older adults, who were the most serious victims of COVID-19 [ 1 , 2 ], had their activities restricted in order to avoid contact with people [ 3 , 4 ]. A previous quasi-experimental study revealed that the number of users of long-term care insurance (LTCI) services was influenced by the pandemic [ 5 ]. A decrease in the number of users of adult day care was particularly evident. At the same time, the decrease in service utilization has simultaneously affected the provider management practices of the service providers [ 6 ].

The LTCI system was launched in Japan in 2000. In 2000, the LTCI system was established to follow the rapid aging. The LTCI system ensures two main types of services: services for convalescent older adults who live at home and services for those who stay in facilities. For those who live at home, there are also two types of services: home-visit services, in which professionals go to the home of the patient to provide services, and day-care services, in which the patient himself/herself goes to the facility during the daytime to receive services at the facility. Most users of LTCI services pay 10% of the total cost of these services out-of-pocket, and the rest is covered by pooled LTCI premiums and taxes. In part, users with sufficient income are asked to pay up to 30% of the total cost.

Under this system, private providers were allowed to provide long-term care services, covered by public insurance [ 7 , 8 ]. This change opened up a market that had previously only been available to providers in a public capacity [ 9 ]. As a result, the number of providers of LTCI services has been increasing every year. For example, the number of facilities providing adult day cares increased from 8,037 in 2000, when the system was first established, to 24,087 in 2020 [ 10 ]. The increase in the number of such providers has also led to an increase in accessibility of use, helping to better maintain the daily lives and activities of those who need care. On the other hand, in the LTCI business, revenue strongly depends on the public’s use of the services. When a user quits using LTCI services, it has a significant impact on the revenue of the provider. In such cases, service management can easily deteriorate, and providers may sometimes close immediately after they have been established.

During the pandemic, some offices were forced to close due to infection control, and there were concerns about managerial difficulties in terms of maintaining the revenues by providing publicly insured LTCI services in Japan. With declining revenues, which lead to unstable finances for establishments and increased risks of bankruptcy [ 11 ], there have been a number of Japanese studies showing the impact [ 12 ] of the pandemic on revenues. That report [ 12 ] revealed about 40% of providers faced a reduction in revenue and also they predicted that reduction continuously. However, there were few studies to show the decline in revenues of LTCI providers with the nationwide scope in Japan. There have also been investigations regarding service scope, in terms of differences in the variety of services offered due to the pandemic’s impact. In a previous study, the decline in number of users was different from that of LTCI services. This present study could suggest the future decline in revenue with the other pandemics or some disasters, and the necessity to consider the preventive measurement for the stopping of services provided. For that future consideration, firstly, the descriptive study to reveal the impact of the pandemic on the LTCI revenue was needed for the current situation with few previous studies. Additionally, time series analysis was effective to capture the impact on the change of revenue compared with the former trend. Therefore, this study aimed to verify the change in revenue experienced by LTCI among service providers in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic, for a variety of services.

Study subjects

In this study, we used anonymized data from “Kaipoke,” a management support platform for older adult care operators provided by SMS Co., Ltd. Kaipoke provides management support services to more than 27,400 care service offices nationwide and has been introduced in many home-care support offices. Study subjects were the LTCI service providers including care management, home-visit care, home-visit nursing, and adult day care which had provided their services in November 2018. We followed up on the subjects’ monthly revenue from December 2018 to November 2020. Kaipoke supports the office works of LTCI service providers including the requirement of revenue, therefore, we could extract the data.

Each service provider of the LTCI system in Japan was certified by a municipal body established by the providers. The municipal body examined the standards for personnel, facilities, and equipment of providers in accordance with the standards set by the national government. Certified providers can provide services for disabled older adults, and claim the expenses to the city as a public insurer.

The outcome of this study was the revenue of LTCI services claimed by the provider. Revenue was recorded in Japanese yen. The exchange rate was set at an average of 113 USD in November 2018, to show global results. The revenue from LTCI services was discussed and revised by the subcommittee of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare once every three years. In recent years, against the backdrop of a shortage of LTC personnel, restructuring within LTCI companies has been increasing. Revenue was standardized throughout the country in the form of “units.” The units were determined on a regional basis between 0.09 USD and 0.10 USD, reflecting the differences in prices and other factors in the region. The LTCI service providers in the region received revenues in yen based on the conversion of the determined unit [ 13 ]. For example, the unit for one service of between 30 min and one hour in home-visit care, mainly with physical assistance, was 394 units in 2018. In the 23 wards of Tokyo, the area with the highest billing rate, this would have been billed at 0.10 USD per unit, for a total of 39.7 USD. The lowest billing rate is 0.09 USD per unit, which would have come out to 34.9 USD for the same service, a difference of 4.8 USD. We used the amount reflecting this regional difference as the outcome.

In this study, the outcome was the amount of revenue received by providers for four types of services: care management, home-visit care, home-visit nursing, and adult day care. The revenue was based on the revenues made in the 2018 revision. Care management [ 14 ] was a service done by a “care manager,” who would make the care plan and prepare the LTC schedule, in liaison and coordination with service providers. A care manager was the only official person to make the care plan, except in the cases of families with qualified members who had completed a certain level of experience and training in care management, and had successfully completed an examination [ 10 , 15 ]. The most recent results showed that care management was paid at 125.7 USD per month per user [ 16 ]. Home-visit care was a service in which a trained person visited the user’s home to provide daily living care such as cleaning and laundry, and physical care such as bathing and toileting. This service is the most widely used home-visit service, with approximately one million users nationwide. Per capita usage was 673.5 USD per month in 2018. Home-visit nursing was primarily provided by nurses. This service included the management of chronic disease conditions or the maintenance of medical treatments such as catheterization. The amount of revenue per user for home-visit nursing was 426.5 USD per month on average. Finally, adult day care was a service that assisted in daily care and training to maintain or improve the user’s physical or psychological functions at the facility, rather than at home. Users took shared buses or private cars to the facility, where several users gathered for activities, meals, and bathing. This care was provided to relieve the users’ senses of social isolation, maintain the users’ physical and psychological functions, and reduce the physical and psychological burdens on the users’ families. The number of adult day care users was the largest among the community-based services, at 1.13 million. The amount of monthly revenue for the usage of this service in 2018 was 820.4 USD.

Certified providers were billed for LTCI on a monthly basis. In this study, the outcome was the amount claimed by each provider for each type of service in the 24 months from December 2018 to November 2020.

The exposure in this study was the new coronavirus infection pandemic. In Japan, the first case of infection was recorded on January 16, 2020. The number of infected individuals has gradually increased since then. The first wave in Japan was confirmed in April 2020, and the daily number of positive cases in the first wave was 720. At that time, little was known about the new coronavirus. Japan was in a state of panic and required people to stay at home. This was followed by a second wave in August 2020 with more than 1,500 positive cases per day. Therefore, in this study, we considered the exposure period as beginning in January 2020, when the pandemic started in Japan.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of monthly revenues of LTCI service providers was described in a time series between December 2018 and November 2020. A summary of the distribution is shown as the means and medians of the revenues (unit: USD). To assess this trend, an interrupted time-series analysis was conducted [ 17 ], in which the outcome was the trend in the amount of monthly revenues of LTCI services (Yt). This analysis was established to observe the interruption of the outcome variable level and trend through the equally spaced periods before and after the introduction of an intervention. In the present study, the intervention of analytical framework was defined for the pandemic of COVID-19. Therefore, we tried to extract the interruption by the pandemic on the LTCI revenue trend. In addition, for that analysis, the assumption was needed that the influences on the outcome variable were stable through the observed periods. We also followed that assumption. The periods were divided into pre-COVID-19 (December 2018-December 2019) and post-COVID-19 (January 2020-November 2020) periods. During the pandemic, the Japanese government issued a declaration of emergency across seven prefectures where the infection had spread [ 18 ]. Thereafter, the state of emergency was expanded to all prefectures. However, seven prefectures, including Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, Chiba, Osaka, Hyogo, and Fukuoka, where emergency declarations were issued earlier, had dense populations and were often the subject of intensive emergency declarations. To capture this difference in areas, we grouped the subjects by a risk area, which included the seven mentioned prefectures, and a control area.

The results were expressed by seven coefficients β 0 - β 7 according to this formula.

β 0 : Estimated the base level;

β 1 : Estimated the trend pre-COVID-19;

β 2 : Estimated the change in level post-COVID-19;

β 3 : Estimated the change in trend post-COVID-19;

β 4 : Estimated the trend in the risk area;

β 5 : Estimated the trend pre-COVID-19 in the risk area;

β 6 : Estimated the change in level post-COVID-19 in the risk area;

β 7 : Estimated the change in trend post-COVID-19 in the risk area.

Here, Tt is the time elapsed each month (1 ≤ Tt ≤ 24) from the start (December 2018) to the end of the observation period (November 2020). Xt was a dichotomous dummy variable that included pre-COVID-19 (Xt = 0) and post-COVID-19 (Xt = 1). Z was also a dummy variable that denoted the area difference: seven prefectures (Z = 1) and other prefectures (Z = 0). A generalized linear model was applied using log link and Poisson distribution. STATA version 14.2 (Stata-Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for the analysis. The results of analysis and figures were output via the STATA syntax “itsa” introduced by Linden [ 19 ]. The statistical significance level was a two-sided p -value of less than 5%.

Ethical issues

This study was conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ethical Review Board in Institution of Medicine, University of Tsukuba. Approval number: 1301). The present study data was completely anonymous without individual information. No personal information was obtained on the part of the researcher for this study. Therefore, disclosure of this study information to the research subjects was done publicly. Patient informed consent was waived by the review board of Institution of Medicine in University of Tsukuba as the data contains no individually identifying information.

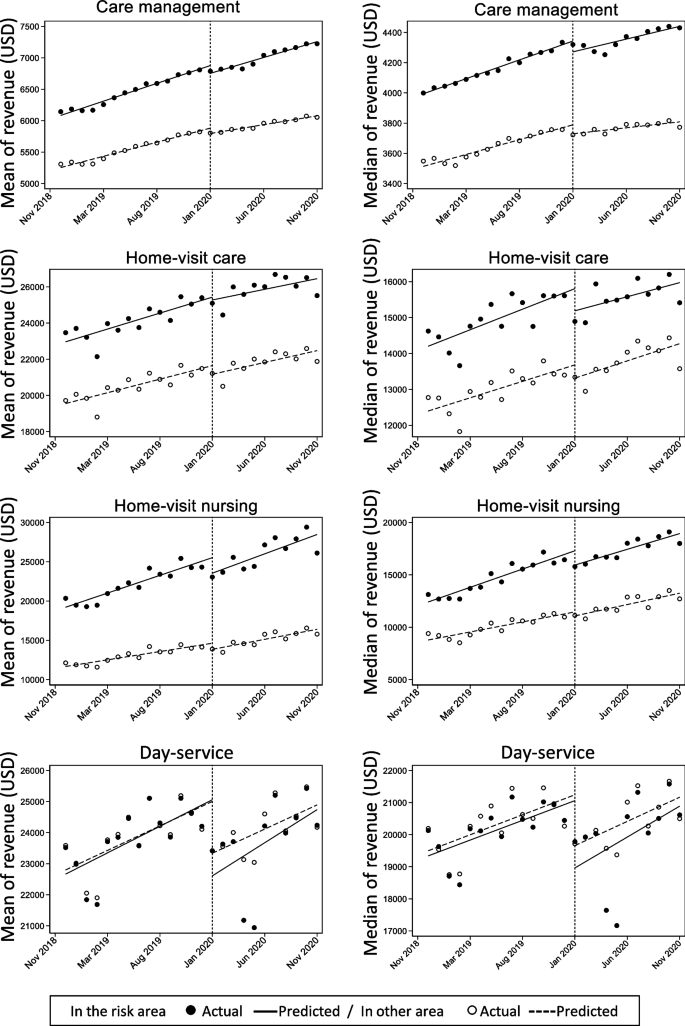

The participating providers were care management providers ( n = 5,767), home-visit care providers ( n = 3,506), home-visit nursing providers ( n = 971), and adult day care providers ( n = 4,650). The breakdown between the seven risk area prefectures where emergency declarations were issued earlier and the other areas (35 prefectures) was close to 50–50 for all service providers. The risk areas were urban and had a larger number of providers between them. The numbers of providers in the risk areas and control areas are listed in Table 1 . For each of the Pre- and Post-COVID-19 periods, we described the mean and median across insurance provider revenues, in 30-day periods. Comparisons of the values between Pre- and Post-COVID-19 showed an increasing trend in all services and areas, except for adult day care in the risk areas. Among adult day care providers in the risk areas, the mean decreased by approximately 100 USD and the median decreased by approximately 200 USD.

In the Fig. 1 , the plots show the actual observed values (dots) and the predicted (regression) lines between the risk and control areas. The regression lines expressed an increasing trend in both the means and medians of all the services and areas during all periods. However, in the case of adult day care, the intercept of the line in Post-COVID-19 declined markedly. The lines for the risk areas were also below those of the others. During the Post-COVID-19, the space between lines widened.

Changes in the revenues (USD) of long-term care insurance services during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan

Table 2 presents the results of our interrupted time-series analysis. For care management, there was a decline in both the level and trend Post-COVID-19. For home-visit care and home-visit nursing, only a decline in the mean level of home-visit care was observed. For adult day care, there were big drops in the means and medians, but the trends did not change.

The results showed that the LTCI revenue of care management providers decreased significantly in terms of both level and trend after the COVID-19 pandemic. The revenue level of home-visit nursing providers also decreased. Finally, in adult day care providers, the level of revenue declined markedly, but the trend did not. In our previous study, the number of users of day services decreased in that trend after the pandemic began. Therefore, as one of the possible reasons, they had restoration of revenue in that trend because the amount of use was increased each individual based on their demands. These nationwide results could be the potential evidence to help the prediction and counter-measurement in the future.

The decrease in the level of revenue among adult day care providers was suggested to have had a serious impact on the sustainability of the business. Prior studies have shown that the decline in the number of adult day care users was significant, which also led to a decrease in revenue for the providers. In adult day care, since people gather and engage in group activities, both users and providers have to be cautious during activities in order to prevent infection. However, the reduction in users may also have influenced the revenue of the providers. Among adult day care providers, approximately 1,600 USD worth of revenue was reduced. A decrease in revenue of about 1,600 USD per month can be equivalent to the salary of one employee [ 20 ]. Aramaki [ 20 ] mentioned the ratio of labor costs tends to be high among long-term care providers, and in adult day care providers it has been reported to be over 60%. In home-visit nursing, the labor cost ratio is even larger, at over 80%. Therefore, employment adjustments may be necessary even for decreases in revenue at an average level of 779 USD. Reductions in revenue can make it difficult for service providers to maintain operations, as well as retain personnel and staff.

In Japan, several surveys have shown concerns regarding the reduction in revenue of LTCI providers. They reported continued year-over-year declines in expenses for personal preventive equipment (PPE) maintenance [ 12 , 21 ]. Some reports suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic may have exacerbated the effects of already unstable management practices, resulting in bankruptcies [ 11 , 22 ]. In the US, the American Health Care Association and the National Center for Assisted Living (AHCA/NCAL) reported that 55% of welfare facilities for older adults operate at a loss, and that 89% of facilities operate at a profit margin of less than 3% [ 23 ]. In addition, many facilities have cited increased costs due to the introduction of additional personnel and PPE for infection control [ 23 ]. In a survey of home-visit care providers in Massachusetts, 80.9% of the 94 providers who responded reported a decrease in home-visit care hours, 98.7% experienced cancellation of visits due to infection concerns, and 64.5% reported that family members took over caregiving of their patients [ 24 ]. The threat of the pandemic forced many lifestyle changes in order to save lives. Among older adults in particular, who are the most at-risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes, changes in the use of long-term care services have been significant. This has affected the management of care centers. Smaller providers in rural areas are more unstable and susceptible to such a decrease in revenue. Typically, these providers are indispensable public resources for maintaining long-term care in the community. Although what we have identified in this study is only a partial decrease in revenue, there is concern that this process will lead to the closure of some providers. It is necessary to continue monitoring the supply of long-term care and the influence of the pandemic. In Japan, financial assistance was provided for LTCI providers suffering from the pandemic, but this was intended to provide necessary PPE and comfort to staff and to supplement insurance, not to compensate for loss of revenue [ 25 ]. In the US, the government helps the Medicare service supplier to recoup the claim to support their financial aspects [ 26 ]. In Japan, the most important thing was to ensure infection prevention, and the care providers were not able to catch up with changes in their finances. The reduction in revenue was not anticipated during the progression of the pandemic. During a pandemic, such as the one that occurred in this study, a decrease in the revenue of LTCI service providers can be expected. The results of this study can hopefully provide suggestions for countermeasures, in addition to support measures already enacted. The number of users and the revenue decreased due to infection control measures. However, it was necessary to maintain staffing to work for infection control for those who continue to use. For the imbalance between the revenue and the number of people employed, we consider that funds defined in the amount of the decrease in users would ensure the maintenance of conventional employment. Additionally, it would contribute to maintaining the quality of services after the pandemic.

This study had several limitations. First, it was a descriptive study and could not provide causal inferences. The data source was an online support system for LTCI providers in Japan. Although the data were available on a national scale, there are concerns regarding their national representativeness. In particular, the scale of the business of LTCI providers was not considered, and the interpretation of the results should be viewed with caution.

This study found that after the beginning of COVID-19, there was a marked decline in LTCI revenue at care management, home-visit nursing, and adult day care providers. The downward trend in adult day care was particularly significant, suggesting an impact on the maintenance of operations for these businesses. These nationwide results could be the potential evidence to help the prediction and counter-measurement in the future. Additional research is needed to determine whether these changes in the revenues of LTCI providers will impact the maintenance of their business operations.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from SMS Co., Ltd. but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648 .

Powell T, Bellin E, Ehrlich AR. Older adults and covid-19: the most vulnerable, the hardest hit. Hastings Cent Rep. 2020;50(3):61–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.1136 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061583 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Roy J, Jain R, Golamari R, et al. COVID-19 in the geriatric population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(12):1437–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5389 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ito T, Hirata-Mogi S, Watanabe T, et al. Change of use in community services among disabled older adults during COVID-19 in Japan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031148 .

Konetzka RT, White EM, Pralea A, et al. A systematic review of long-term care facility characteristics associated with COVID-19 outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(10):2766–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17434 .

Ikegami N. Financing long-term care: lessons from Japan. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2019;8(8):462–6. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2019.35 .

Campbell JC, Ikegami N. Long-term care insurance comes to Japan. Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(3):26–39.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Report of long-term care insurance. Ministry of Health, Labour and Werfare website. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/84-1 . Accessed 30 May 2023.

How is the certification of need for nursing care done? Ministry of Health, Labour and Werfare website. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/hukushi_kaigo/kaigo_koureisha/nintei/gaiyo2 . Accessed 30 May 2023.

Bankruptcies in the elderly welfare and nursing care business in 2020 [in Japanese]. Tokyo Shoko Research website. https://www.tsr-net.co.jp/news/analysis/20200108_00 . Accessed 30 May 2023.

Survey of social welfare corporation management trends [in Japanese]. Welfare And Medical Service Agency website. https://www.wam.go.jp/hp/sh-survey/ . Accessed 30 May 2023.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Werfare. Conversion of determined unit. 2019.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Werfare. Care management. 2017.

Tsutsui T, Muramatsu N. Care-needs certification in the long-term care insurance system of Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):522–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53175.x .

Ministry of Health, Labour and Werfare. Statistics of benefits from long-term care insurance [in Japanese] (Kaigo Kyuhu-Hi-Tou Jittai Toukei). 2021.

Lopez Bernal J, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw098 .

Article Google Scholar

Japan's response to the novel coronavirus disease: declaration of a state of emergency. Japan Cabinet Office. Website. https://corona.go.jp/news/news_20200421_70 . Accessed 30 May 2023.

Linden A. Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single- and multiple-group comparisons. Stata J. 2015;15(2):480–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1501500 .

Aramaki T. Management status of day care facilities in fiscal year 2017 [in Japanese]. Welfare And Medical Service Agency website. https://www.wam.go.jp/hp/wp-content/uploads/190628_No002.pdf2019 . Accessed 30 May 2023.

Report on the impact of the new corona - corporate management in the era of corona in 2020 [in Japanese]. Survey and Research Committee, Council of Managers of Social Welfare Corporations website. https://www.tcsw.tvac.or.jp/chosa/documents/keieichousazennbunn.pdf . Accessed 30 May 2023.

Survey on closure and dissolution of welfare and nursing care businesses for the elderly in 2020 [in Japanese]. Tokyo Shoko Research website. https://www.tsr-net.co.jp/news/analysis/20210120_01 . Accessed 30 May 2023.

Amarican Health Care Association. Nursing homes incurring significant costs and financial hardship in response to COVID-19. In: National Center For Assisted Living. https://www.ahcancal.org/News-and-Communications/Fact-Sheets/FactSheets/Survey-SNF-COVID-Costs.pdf . Accessed 30 May 2023.

Sama SR, Quinn MM, Galligan CJ, et al. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on home health and home care agency managers, clients, and aides: a cross-sectional survey, March to June, 2020. Home Health Care Management, Practice. 2021;33(2):125–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822320980415 .

Ministry of Health, Labour and Werfare. Support project for infection control measures at nursing care service establishments and facilities, etc., and project to provide consolation money to employees [in Japanese]. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000121431_00245 . Accessed 30 May 2023.

CMS. COVID-19 accelerated and advance payments. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/covid-19/covid-19-accelerated-and-advance-payments . Accessed 11 Dec 2023.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This work was supported by SMS Co., Ltd, grant number CRE30018, at the University of Tsukuba.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Medicine, University of Tsukuba, 1-1-1 Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, 305-8575, Japan

Tomoko Ito & Nanako Tamiya

Health Services Research and Development Center, University of Tsukuba, 1-1-1 Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, 305-8575, Japan

Tomoko Ito, Xueying Jin, Makiko Tomita & Nanako Tamiya

Department of Social Science, National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, 7- 430 Morioka-cho, Obu, Aichi, 474-8511, Japan

Xueying Jin

Analysis & Innovation Dept., SMS Co., Ltd., Sumitomo Fudosan Shibakoen Tower, 2-11-1, Shibakoen, Minato-ku, Tokyo, 105-0011, Japan

Makiko Tomita & Shu Kobayashi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All jointly designed the study, TI conducted all data analysis, TI wrote first and all drafts of manuscript. XJ, MT, SK, and NT provided critical feedback and helped improve the research, analysis and manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tomoko Ito .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the review board of Institution of Medicine in University of Tsukuba. No personal information was obtained on the part of the researcher for this study. Therefore, disclosure of this study information to the research subjects was done publicly. Patient informed consent was waived by the review board of Institution of Medicine in University of Tsukuba as the data contains no individually identifying information.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

This research was supported by SMS Co., Ltd. and was conducted as a part of the joint research between SMS Co., Ltd. and University of Tsukuba. NT received the fund by SMS Co., Ltd. as the principal investigator of the joint research. MT was a researcher at the University of Tsukuba for joint research with SMS Co., Ltd. in the 2023 financial year (i.e., April 2023 to March 2024). MT and SK were employed by SMS Co., Ltd. TI and XJ had no conflict of interest to be disclosed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ito, T., Jin, X., Tomita, M. et al. Changes in long-term care insurance revenue among service providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Health Serv Res 24 , 464 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10832-4

Download citation

Received : 06 June 2023

Accepted : 06 March 2024

Published : 13 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-10832-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Long-term care services

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Home Health Nurse Decision-Making Regarding Visit Intensity Planning for Newly Admitted Patients: A Qualitative Descriptive Study

Elliane irani.

Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA

Karen B. Hirschman

School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Pamela Z. Cacchione

Kathryn h. bowles.

School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA; Center for Home Care Policy and Research, Visiting Nurse Service of New York, NY, USA

Despite patients referred to home health having diverse and complex needs, it is unknown how nurses develop personalized visit plans. In this qualitative descriptive study, we interviewed 26 nurses from three agencies about their decision-making process to determine visit intensity and analyzed data using directed content analysis. Following a multifactorial assessment of the patient, nurses relied on their experience and their agency’s protocols to develop the personalized visit plan. They revised the plan based on changes in the patient’s clinical condition, engagement, and caregiver availability. Findings suggest strategies to improve visit planning and positively influence outcomes of home health patients.

The demand for home health (HH) care services is increasing due to the growing aging population, rising rates of chronic conditions, and advances in the provision of health-related services in patients’ homes. In 2014, there were 12,461 HH agencies serving 3.4 million Medicare beneficiaries at a cost of 17.9 billion U.S. dollars ( Medicare Payment Advisory Commission [MedPAC], 2016 ). Patients receiving HH services have complex needs ( Murtaugh et al., 2009 ) and require different levels of care and attention. Visit intensity specifically refers to the number and frequency of visits that patients receive throughout the 60-day care episode ( O’Connor et al., 2014 ). While there is some available data on the impact of visit intensity on outcomes for HH care in the United States ( O’Connor, Hanlon, Naylor, & Bowles, 2015 ; O’Connor et al., 2014 ), empirical evidence about nurse decision-making regarding visit intensity planning does not exist. Despite this, nurses are required to make such decisions daily for newly admitted patients, which annually equates to 6.6 million decisions ( MedPAC, 2016 ). Therefore, we sought to answer the following question: How do HH nurses decide on visit intensity and what factors influence these decisions?

Visit Planning and Patient Outcomes

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) mandates that patients admitted to HH care receive an initial assessment within 48 hours of referral or within 48 hours of their return home ( CMS, 2015 ). However, there are no requirements or recommendations regarding the timing, number, and frequency of subsequent visits. Half of unplanned rehospitalizations among HH patients occur within the first two weeks following admission to HH care ( Rosati & Huang, 2007 ), when patients are at greatest risk for poor health outcomes ( Krumholz, 2013 ). This highlights the critical role of HH nurses who provide personalized care and are attentive to early cues of health decline while a hospital admission is avoidable.

Providing more visits in the first few weeks of the HH episode allows nurses to maximize teaching opportunities, provide surveillance, and identify issues early on, thus contributing to decreased rates of rehospitalization ( Rogers, Perlic, & Madigan, 2007 ). This practice has been referred to in the literature as frontloading , recently defined as providing “at least one nursing visit on the day of or day after hospital discharge and at least three nursing visits (including the first visit) in the first posthospital week” ( Murtaugh et al., 2017 , p. 5). Although initial intensive assessment is key for early interventions, maintaining a steady pattern of visits can also influence patient outcomes. The total number of skilled nursing visits in a care episode and the HH length of stay also influence the likelihood of hospital readmissions ( O'Connor et al., 2015 ). Therefore, nurses can assist in reducing hospital readmission by providing an adequate number and frequency of skilled nursing visits, otherwise known as visit intensity.

Decision-Making and Nursing Practice

Decision-making is a complex process that involves analysis and intuition, which are inherently connected ( Banning, 2008 ). Nurses routinely use these interrelated patterns of reasoning to make decisions that influence patient care and outcomes ( Tanner, 2006 ). Previous research highlights the importance of knowing the patient and family in order to make appropriate clinical decisions ( Egan et al., 2009 ; Smith Higuchi, Christensen, & Terpstra, 2002 ; Stajduhar et al., 2011 ). Decision-making also relies on personal values and professional scope of practice ( Gillespie & Paterson, 2009 ), as well as prior experiences with similar situations, which facilitates the evaluation and weighing of potential decisional alternatives ( Tversky & Kahneman, 1974 ). HH organizational factors such as the level of support from managers and peers influence how nurses engage in decision-making and care delivery ( Ellenbecker, Boylan, & Samia, 2006 ; Flynn, 2007 ; Tullai-McGuinness, Riggs, & Farag, 2011 ). Also, HH policy and payment factors influence care delivery. Since the implementation of the prospective payment system in 2000, the number of visits per HH user over a yearlong period was reduced by more than half ( MedPAC, 2017 ). However, it is unclear to what extent this drop in visits is related to the interplay between nurses’ autonomy in developing visit plans and other agency and policy factors that may influence their decisions.

Conceptual Framework